Stereotypical hand movements in 144 subjects with Rett syndrome from the population-based Australian...

-

Upload

philippa-carter -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Stereotypical hand movements in 144 subjects with Rett syndrome from the population-based Australian...

Stereotypical Hand Movements in 144 Subjects with RettSyndrome from the Population-Based Australian Database

Philippa Carter, MBBS,1 Jenny Downs, PhD,1,2 Ami Bebbington, BSc (Hons),1

Simon Williams, MBBS,3 Peter Jacoby, MSc,1 Walter E. Kaufmann, MD,4

and Helen Leonard, MBChB1*

1Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, Centre for Child Health Research, The University of Western Australia,West Perth, Western Australia

2School of Physiotherapy and Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute, Curtin University of Technology, Perth,Western Australia

3Departments of Neurology and Pediatric Rehabilitation, Princess Margaret Hospital, Roberts Road, West Perth,Western Australia

4Center for Genetic Disorders of Cognition and Behaviour, Kennedy Krieger Institute and Johns Hopkins University School ofMedicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Video

Abstract: Stereotypic hand movements are a feature ofRett Syndrome but few studies have observed their naturesystematically. Video data in familiar settings wereobtained on subjects (n 5 144) identified from an Austra-lian population-based database. Hand stereotypies weredemonstrated by most subjects (94.4%), 15 categories wereobserved and midline wringing was seen in approximately60% of subjects. There was a median of two stereotypiesper subject but this number decreased with age. Clappingand mouthing of hands were more prevalent in girlsyounger than 8 years and wringing was more prevalent inwomen 19 years or older. Clapping was commoner inthose with p.R306C and early truncating mutations, and

much rarer in those with p.R106W, p.R270X, p.R168X,and p.R255X. Stereotypies tended to be less frequent inthose with more severe mutations. Otherwise, there wereno clear relationships between our categories of stereoty-pies and mutation. Approximately a quarter each had pre-dominantly right and left handed stereotypies and for theremaining half, no clear laterality was seen. Results weresimilar for all cases and when restricted to those with apathogenic mutation. Hand stereotypies changed withincreasing age but limited relationships with MECP2 muta-tions were identified. � 2009 Movement Disorder SocietyKey words: Rett syndrome; video recording; stereotypic

movement disorder; genotype; hand function

INTRODUCTION

Rett syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder

affecting mainly females with an incidence of approxi-

mately 1 in 8,500 live female births.1 Diagnosis is

based on clinical findings as set out in revised diagnos-

tic criteria.2 Of these criteria, one of the most well rec-

ognised features of Rett syndrome is the development

of stereotypic hand movements. An associated feature

is loss of purposeful hand skills between 6 months

and 3 years. Since the discovery of the link between

mutations at the MECP2 gene and the clinical entity of

Rett syndrome, relationships between specific muta-

tions and a range of clinical characteristics have been

reported.3,4

Literature on hand stereotypies in Rett syndrome has

in the past been limited and inconsistent.5–12 Given the

known heterogeneity of this disorder,13 the demon-

strated relationships between genotype and pheno-

type,3,4 and the tendency for the symptoms to change

Potential conflict of Interest: nothing to report.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the onlineversion of this article.

*Correspondence to: Dr. Helen Leonard; Telethon Institute forChild Health Research, Centre for Child Health Research, TheUniversity of Western Australia, PO Box 855, West Perth 6872, WA,Australia.E-mail: [email protected]

Received 4 June 2009; Revised 7 September 2009; Accepted 25September 2009

Published online 11 November 2009 in Wiley InterScience

(www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/mds.22851

282

Movement DisordersVol. 25, No. 3, 2010, pp. 282–288� 2009 Movement Disorder Society

with increasing age,14 similar patterns might be

expected with hand stereotypies. One recent case series

(n 5 83) demonstrated variability in stereotypies

including the reporting of fifteen different hand

movements.15 However subjects had been assessed in

clinical settings and relationships with specific MECP2mutations not explored. Hence there is a need for this

research to be extended and further developed.

We have collected video material on a large number

of cases representative of a population-based cohort,16

and investigated variation in stereotypies with age and

genotype. We predicted that we would find a wide

range of stereotypies, and that there would be differen-

ces in these movements between younger and older

subjects and an association with genotype. We also

investigated relationships between characteristics of

hand stereotypies and their frequency and laterality of

hand us.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The Australian Rett Syndrome Database (ARSD) is

a population-based register of Rett syndrome cases in

Australia.1,17,18 In 2004 and 2007, families whose chil-

dren were subjects in the ARSD were asked to partici-

pate in a video study and were sent instructions for

filming specific aspects of their child’s activities of

daily living.16 This article describes the hand stereoty-

pies as observed on the first video received from indi-

vidual children and women.

A coding sheet was developed based upon Jan-

kovic’s definition of stereotypy19 recording the type of

hand movement seen, the position of the hands (joined

or separated) and the dominant hand (if asymmetrical).

Categories of stereotypies of joined hands comprised

wringing/clasping/washing, clapping, and mouthing;

and of separated hands, mouthing, clasping, tapping,

hair pulling, flapping, hand gaze, hand behind the

neck, hair twirling, and ‘‘sevillana’’ (a term describing

sequential flexion of metacarpophalangeal and inter-

phalangeal joints from fifth to second digits). Stereoty-

pies that did not fit into any of these groups were

categorised as ‘‘other- joined’’ or ‘‘other- separate’’ and

were described in detail. Stereotypies that involved

extensive use of upper limb joints were categorised

as ‘‘complex arm movements’’. Pill-rolling tremor

and movements related to dystonia, e.g. twisting of

the fingers were not classified as hand stereotypies.

Coding was conducted by a physician and physiothera-

pist blinded to mutation status. Viewing and discussion

of coding were repeated frequently to maintain consis-

tency of categorization. Stereotypies that were

difficult to categorize were discussed with a pediatric

neurologist.

Supporting information about frequency of hand

stereotypies, handedness and ages of stereotypy onset

and loss of hand skills were obtained from question-

naires administered to families in 2004 and 2006.20

Subjects with a known pathogenic mutation were cate-

gorized by genotype (p.R106W, p.R133C, p.T158M,

p.R168X, p.R255X, p.R270X, p.R294X, p.R306C, C-

terminal deletions, early truncating mutations, large

deletions, and other). This study was approved by the

ethics committee at Princess Margaret Hospital for

Children, Western Australia and families provided

written consent.

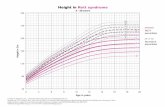

To assess the representativeness of the our sample,

the age-group at the time of video for the 144 subjects

was compared with the age-group mid-way through

2004 for the 153 subjects known to the Australian Rett

Syndrome Database who never provided a video. Sub-

jects who provided a video were more likely to be

younger than 8 years (25.0 vs 17.6%) and less likely

to be 8 � 13 years (17.4 vs 32.0%) (p 5 0.366). The

distribution of mutation positive cases (p 5 0.411) and

of mutation types (p 5 0.631) were similar for the two

groups.

Data Management and Analysis

Age was grouped into four categories representing

the preschool and early school years (0–8 years), pri-

mary school (8–13 years), adolescent years (13–19

years), and adult years (>19 years). Chi squared tests

and gamma tests of association were used to assess

relationships between categorical variables. All analy-

ses were undertaken using Stata 9.21 Results have been

provided for the overall group, and separately for sub-

jects with a pathogenic mutation. P values of <0.05

were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Video data were available for 144 females with con-

firmed Rett syndrome. The median age at the time of

video was 14.6 years (range 2–31.8 years). Of the 140

who had been genetically tested 110 (78.6%) had a

pathogenic mutation identified (Table 1).

Stereotypies were observed in 136/144 (94.4%) of

all cases and in 106/110 (96.4%) of those with a patho-

genic mutation. Fifteen categories of hand stereotypies

were observed (Table 2; Video), the most common

being a midline wringing action seen in 85 (59.0%) of

all subjects and 68 (61.8%) of those mutation positive.

283HAND STEREOTYPIES IN RETT SYNDROME

Movement Disorders, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2010

The median number of specific hand stereotypies per

subject was two (range 0–6). The number per subject

decreased with age with 58.8% (51.7% if mutation

positive) of those younger than 8 years having three or

more stereotypies compared with 32.5% (25.0% if

mutation positive) in those older than 19 years (p 50.02). Some specific stereotypies, such as clapping, sin-

gle-handed, and bilateral-handed mouthing also became

less prevalent with increasing age in contrast to hand

wringing, which did not follow this pattern (Table 3).

There was some variation in type of hand sterotypy by

mutation type with hand clapping (Table 2) being most

frequent and hand wringing less frequent in those with

p.306C and early truncating mutations. Single handed

mouthing was commoner in those with p.R306C and in

C terminal deletions and bilateral mouthing commoner

in those with p.T158M.

Slightly less than half (47.0% overall; 46.2% if

mutation positive) of subjects showed no clear lateral-

ity (dominance) of their hand stereotypies, 27.2%

(26.4% if mutation positive) had predominantly left-

sided and 25.7% (27.4% if mutation positive) predomi-

nantly right-sided stereotypies. There was a slight

increase in prevalence of left-handedness in those with

left dominant stereotypies. Nearly half (48.0%) of

those with left-dominant stereotypies were left-handed,

36.0% right-handed, and 16.0% had equal functional

hand use whilst three-fifths (60.0%) of those with

TABLE 1. Number (%) of subjects in each age-group andwith each common mutation

All cases(n 5 144)Number (%)

Cases with aconfirmedpathogenicmutation(n 5 110)Number (%)

Age-group < 8 years 36 (25.0) 30 (27.3)8 < 13 years 25 (17.4) 19 (17.3)13 < 19 years 40 (27.8) 27 (24.5)‡ 19 years 43 (29.9) 34 (30.9)

Mutation C terminal 12 (8.3) 12 (10.9)Early truncating 4 (2.8) 4 (2.8)p.R106W 5 (3.5) 5 (4.6)p.R133C 12 (8.3) 12 (10.9)p.R168X 11 (7.6) 11 (10.0)p.R255X 9 (6.2) 9 (8.2)p.R270X 10 (6.9) 10 (9.1)p.R294X 12 (8.3) 12 (10.9)p.R306C 5 (3.5) 5 (4.6)p.T158M 9 (6.2) 9 (8.2)Large deletions 6 (4.2) 6 (5.4)Other mutations 14 (9.7) 14 (12.7)No confirmed

pathogenic mutation34 (23.6)

TABLE

2.Num

ber(percentag

e)of

allsubjects

andsubjectswitheach

ofthecommon

mutations

foreach

catego

ryof

hand

stereotypy*

Allcases

(n5

144)

Cterm

inal

(n5

12)

Early

truncating

(n5

5)

p.R106W

(n5

5)

p.R133C

(n5

12)

p.R168X

(n5

11)

p.R255X

(n5

9)

p.R270X

(n5

10)

p.R294X

(n512)

p.R306C

(n5

5)

p.T158M

(n5

9)

Large

deletions

(n5

6)

Other

mutations

(n5

14)

Pvalue

Wringing

85(59.0%)

9(75.0)

1(20.0)

2(40.0)

7(58.3)

6(54.6)

5(55.6)

7(70.0)

10(83.3)

1(20.0)

7(77.8)

3(50.0)

10(71.4)

0.218

Mouthingonehand

58(40.3%)

8(66.7)

1(20.0)

1(20.0)

6(50.0)

3(27.3)

2(22.2)

6(60.0)

6(50.0)

4(80.0)

2(22.2)

1(16.7)

4(28.6)

0.125

Claspingonehand

56(38.9%)

4(33.3)

2(40.0)

2(40.0)

4(33.3)

6(54.6)

3(33.3)

5(50.0)

3(25.0)

1(20.0)

3(33.3)

3(50.0)

4(28.6)

0.945

Clapping

39(27.1%)

3(25.0)

3(60.0)

0(0.0)

6(50.0)

1(9.1)

1(11.1)

0(0.0)

2(16.7)

3(60.0)

4(44.4)

1(16.7)

3(21.4)

0.036

Tapping

27(18.8%)

2(16.7)

1(20.0)

0(0.0)

2(16.7)

3(27.3)

1(11.1)

0(0.0)

3(25.0)

2(40.0)

0(0.0)

1(16.7)

2(14.3)

0.625

Mouthingjoined

hands

15(10.4%)

1(8.3)

1(20.0)

0(0.0)

1(8.3)

2(18.2)

2(22.2)

0(0.0)

2(16.7)

0(0.0)

4(44.4)

0(0.0)

1(7.1)

0.223

Other

onehand

11(7.6%)

2(16.7)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

2(16.7)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(10.0)

1(8.3)

1(20.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(7.1)

0.713

Other

joined

hands

10(6.9%)

1(8.3)

0(0.0)

1(20.0)

1(8.3)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(10.0)

2(16.7)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(7.1)

0.787

Hairpulling

9(6.2%)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

2(16.7)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(10.0)

3(25.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(16.7)

1(7.1)

0.331

Sevillana

9(6.2%)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(9.1)

1(11.1)

2(20.0)

1(8.3)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(7.1)

0.684

Complexarm

movem

ent

6(4.2%)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(9.1)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(8.3)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(7.1)

0.861

Flapping

5(3.5%)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(8.3)

1(9.1)

1(11.1)

0(0.0)

1(8.3)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0.848

Handgaze

3(2.1%)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(11.1)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(7.1)

0.696

Handbehindhead

2(1.4%)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

1(7.1)

0.806

Hairtwirling

1(0.7%)

1(8.3)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0(0.0)

0.692

*percentages

ineach

columndonotaddupto

100%

because

each

subject

could

havemore

than

onestereotypy.

284 P. CARTER ET AL.

Movement Disorders, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2010

right-dominant stereotypies were right-handed, 35.0%

left-handed, and 5.0% had equal functional hand use.

Data describing the frequency of stereotypies were

available for 131 subjects. The vast majority of sub-

jects (119, 90.8%) had ‘constant’ to ‘frequent’ hand

stereotypies daily, and few had ‘weekly’ (8, 6.5%) or

‘rare’ to ‘never’ (4, 3.1%) frequencies of stereotypies.

Over half (7/12 58.3%) of individuals with p.R294X

and 5/11 (45.5%) of subjects with C-terminal muta-

tions had ‘constant’ stereotypies, compared with 2/5

(40%) with p.R306C, 5/13 (38.5%) with other muta-

tions, 3/8 (37.5%) with p.R255X, 3/9 (33.3%) with

p.R133C, 2/6 (33.3%) with large deletions, 3/11

(27.3%) with p.R168X, 1/4 (25%) with p.R106W, and

2/9 (22. 2%) with p.T158M mutations. No subjects

with early truncating or p.R270X mutations had ‘con-

stant’ stereotypies.

DISCUSSION

A large variety of stereotypical hand movements

was observed in our cohort, the most commonly

observed stereotypy being hand wringing. Most sub-

jects had more than one type of stereotypy, the number

per subject decreased with age, and clapping and

mouthing were less prevalent in the older women.

Findings were similar for the total group of subjects

and for those with pathogenic mutation. Those with

mutations recognized to be more severe were less

likely to have constant steretoypies or to demonstrate

clapping or mouthing stereotypies.

This study was able to assess hand stereotypies in a

large sample of Australian subjects identified from the

Australian Rett Syndrome Database.1,16 Thus, our find-

ings are likely to be broadly representative of patients

with this uncommon disorder. In this analysis, we

examined the findings for both the whole group with a

clinical diagnosis of Rett syndrome, irrespective of

genetic status as well as separately for those, in which

a pathogenic mutation has been identified. We thought

it was important as had the Portuguese study of

83 cases,15 not to exclude those cases who were either

mutation negative or for whom there had not been the

opportunity for genetic testing. Of those who were

mutation negative, not all would have had the full

range of MECP2 testing for large deletions and exon 1

mutations. Therefore, it is still possible that some of

these cases do have a not yet identified MECP2 muta-

tion or one involving the CDKL522 or FOXG123genes.On the other hand, we also presented the results for

the known MECP2 positive group, as they represent

the group for whom the clinical diagnosis of Rett syn-

TABLE

3.Distributionof

differenttypesof

hand

stereotypies

forthedifferentag

e-grou

pcatego

ries

forallcasesan

dcaseswithaknow

npa

thog

enic

mutation

Allcases(N

5144)

Cases

withaknownpathogenic

mutation(N

5110)

<8years

(n5

36)

8<

13years

(n5

25)

13<

19years

(n5

40)

‡19years

(n5

43)

Pvalue

<8years

(n5

30)

8<

13years

(n5

19)

13<

19years

(n5

27)

‡19years

(n5

34)

Pvalue

Wringing

16(44.4%)

16(64.0%)

23(57.5%)

30(69.8%)

0.138

13(43.3%)

12(63.2%)

19(70.4%)

24(70.6%)

0.098

Mouthingonehand

20(55.6%)

11(44.0%)

14(35.0%)

13(30.2%)

0.116

18(60.0%)

8(23.5%)

10(37.0%)

8(23.5%)

0.030

Claspingonehand

16(44.4%)

9(36.0%)

16(40.0%)

15(34.9%)

0.834

11(36.7%)

8(42.1%)

9(33.3%)

12(35.3%)

0.941

Clapping

17(47.2%)

6(24.0%)

10(25.0%)

6(14.0%)

0.010

13(43.3%)

3(15.8%)

7(25.9%)

4(11.8%)

0.023

Tapping

9(25.0%)

4(16.0%)

8(20.0%)

6(14.0%)

0.629

6(20.0)

3(15.8%)

5(18.5%)

3(8.8%)

0.612

Mouthingjoined

hands

10(27.8%)

2(8.0%)

2(5.0%)

1(2.3%)

0.001

10(33.3%)

1(5.3%)

2(7.4%)

1(2.9%)

0.001

Other

onehand

2(5.6%)

0(0.0%)

4(10.0%)

5(11.6%)

0.311

1(3.3%)

0(0.0%)

4(14.8%)

3(8.8%)

0.205

Other

joined

hands

3(8.3%)

1(4.0%)

3(7.5%)

3(7.0%)

0.927

3(10.0%)

1(5.3%)

2(7.4%)

1(2.9%)

0.700

Hairpulling

0(0.0%)

3(12.0%)

3(7.5%)

3(7.0%)

0.266

0(0.0%)

3(15.8%)

2(7.4%)

3(8.8%)

0.211

Sevillana

2(5.6%)

2(8.0%)

2(5.0%)

3(7.0%)

0.959

1(3.3%)

2(10.5%)

1(3.7%)

2(5.9%)

0.710

Complexarm

movem

ent

2(5.6%)

2(8.0%)

1(2.5%)

1(2.3%)

0.629

1(3.3%)

0(0.0%)

1(3.7%)

1(2.9%)

0.879

Flapping

2(5.6%)

1(4.0%)

1(2.5%)

1(2.3%)

0.857

2(6.7%)

1(5.3%)

0(0.0%)

1(2.9%)

0.573

Handgaze

0(0.0%)

1(4.0%)

2(5.0%)

0(0.0%)

0.284

0(0.0%)

1(5.3%)

1(3.7%)

0(0.0%)

0.394

Handbehindhead

0(0.0%)

0(0.0%)

0(0.0%)

2(4.6%)

0.190

0(0.0%)

0(0.0%)

0(0.0%)

1(2.9%)

0.521

Hairtwirling

0(0.0%)

1(4.0%)

0(0.0%)

0(0.0%)

0.188

0(0.0%)

1(5.3%)

0(0.0%)

0(0.0%)

0.184

285HAND STEREOTYPIES IN RETT SYNDROME

Movement Disorders, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2010

drome has been validated with genetic testing. Overall

there were few differences between the two groups.

Parents or carers provided the video footage in

familiar surroundings and a realistic view of the

movements as they occur under normal circumstan-

ces.16 This study used a strict definition of stereo-

typy,19 and in doing so, ensured that the dystonic pos-

turing and athetoid movements seen in some of the

subjects were not coded as stereotypies. One limitation

of video observation lies in the two dimensional repre-

sentation of a three dimensional activity, which might

allow smaller details of the hand movements to be

overlooked. Further, this study was cross-sectional but

we are planning longitudinal analysis to assess change

over time for each subject.

Fifteen different categories of hand stereotypies

were identified. Approximately half of subjects demon-

strated typical hand-wringing movements and mouth-

ing, a clasping action in one hand only, and hand clap-

ping were also commonly observed. Our findings are

broadly consistent with those of a recent clinical

study15 but we observed clapping more frequently and

mouthing less frequently in our subjects. These differ-

ences could relate to our larger sample size, which was

also representative of the Australian population with

Rett syndrome and the familiar settings, in which

observations were made.

Supported by previous findings in the literature,15,24

our study has shown a decrease in the number of dif-

ferent hand stereotypies with increasing age. This

diminishing variety of stereotypies is consistent with

an overall picture of movement restriction in older

women with Rett syndrome.14,25 We acknowledge

again that in this study we were only able to assess

cross-sectional relationships and a future longitudinal

study would be of additional value. The prevalence of

the most commonly seen stereotypy, hand wringing,

did appear to increase slightly with age, whereas

mouthing, clasping, tapping, and clapping decreased

with age. This might suggest that different mechanisms

exist for the maintenance of stereotypies. Furthermore,

the fact that the prevalence of hand wringing remained

consistently high at a range of ages although that of

others reduced with age might prove useful when diag-

nozing patients at different ages.

The relationships we found between specific muta-

tion and stereotypy, as classified in this study, were

fairly minimal. Clapping was more likely to be demon-

strated by subjects with the p.R306C mutation, a muta-

tion that is associated with milder severity3,4,26 and

later onset of hand stereotypies,3 but was less likely to

be demonstrated by subjects with the more severe

mutations.3,4 Stereotypies such as hand-wringing were

seen in all mutations although were more frequently

observed with certain mutations (C terminal, p.T158M,

and p.R294X). A recent study examining various

movement disorders seen in Rett syndrome 27 did not

find any relationship between frequency or number of

stereotypies and genotype, although the categorization

of genotypes was limited to missense (n 5 26) and

truncating mutations (n 5 34). Therefore, few relation-

ships between genotype and hand stereotypies have

been identified. In contrast, hand function appears to

be better associated with genotype in line with other

phenotypical features.3,4 However compared with our

work using international data involving 346 cases with

pathogenic mutations,3 our current sample size of 110

is relatively small because it depends on the collection

of video material currently only available in our Aus-

tralian study.1,16 Therefore our results could have been

compromised by limited statistical power. As the neu-

rological processes underlying hand stereotypies are

not yet understood we have coded each stereotypy as a

descriptive category. With increasing knowledge of the

pathophysiology of these movements, an improved

method of classification of observations may become

apparent. Furthermore, factors other than specific

MECP2 mutation are already known to influence se-

verity of the disorder, such as X inactivation status28

and the presence of a certain polymorphism in the

BDNF gene.29 As our understanding of neurological,

genetic, and environmental processes improves, clearer

relationships between genotype and stereotypies may

be revealed.

Those with asymmetrical hand stereotypies (right or

left dominant) were slightly more likely to have ipsilat-

eral handedness. Physiological hand stereotypies in

normal child development are precursors to higher

manual skills and therefore might be expected to have

corresponding dominance.30 If handedness was contra-

lateral, that might infer that the stereotypies or their

synaptic pathways were interfering with purposeful

hand function (i.e. the dominant hand is used because

it is the least affected by stereotypies). The trend we

have shown suggests that the developmental process

itself, which tailors synaptic pathways converting ster-

eotypical movements into purposeful ones, has been in-

terrupted.

Recent research investigating physiological stereoty-

pies has shown a disproportionate reduction in volume

of the frontal lobe white matter and decreased volume

of the caudate nuclei,31 suggesting that cortico-striatal-

thalamo-cortical pathways may be involved in the de-

velopment of stereotypies. A recent imaging study

286 P. CARTER ET AL.

Movement Disorders, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2010

showed that selective grey matter reductions in the

dorsal parietal lobe were characteristic of Rett syn-

drome and suggested that this abnormality could be

related to deficits in sequential movements and tactile

information processing.32 Further, the magnitude of

reduction in volume of the frontal lobe was related to

overall clinical severity.32 Thus, stereotypies in Rett

syndrome may reflect structural and functional abnor-

malities of multiple cortico–subcortical pathways.

Studies like this could help elucidate the neural circuits

and in turn, such investigations into the neurobiological

basis of Rett syndrome might guide future studies of

the relationship between genotype and phenotype.

In conclusion, this study represents the first compre-

hensive examination of one of the key clinical features

of Rett syndrome in a population-based cohort. While

hand stereotypies appear to change over time along

with most other features of the disorder, they seem to

be unique in their limited relationship with MECP2mutations.

LEGEND TO THE VIDEO

Categories of hand stereotypies observed in subjects

with Rett syndrome of various ages and mutations.

Acknowledgments: The video component of AustralianRett Syndrome program was funded by the National Medicaland Health Research Council (NHMRC) under project grant303189 and major aspects of the research program werefunded by the National Institutes of Health (1 R01 HD43100-01A1). HL is funded by NHMRC program grant 353514 andWEK by NIH grant P01 HD24448.

Financial disclosures: Philippa Carter–Employment:Registrar in Psychiatry, Princess Margaret Hospital for Chil-dren (public practice), Perth; Jenny Downs–Employment:Senior Research Officer, Telethon Institute for Child Health,Perth and Lecturer, School of Physiotherapy, Curtin Univer-sity of Western Australia; Ami Bebbington–Employment:Biostatistician, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research,Perth; Simon Williams–Employment: Consultant Neurologistin public practice, Perth; Peter Jacoby–Employment: Biosta-tistician, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, Perth;Walter E. Kaufmann–Consultancies: NIH and biomedicalfoundations (Autism Speaks, IRSF*) grant review, Advisoryboards: IRSF, American Psychiatric Association (DSM-VCommittee), Employment: Director of the Center for GeneticDisorders of Cognition and Behavior, Kennedy Krieger Insti-tute, USA; Helen Leonard–Employment: Clinical AssociateProfessor, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research,Perth.

Author Roles: Philippa Carter was involved in ResearchProject (conception, organization, and execution), StatisticalAnalysis (design, execution, and critique) Manuscript(Writing first draft and Critique); Jenny Downs was involvedin Research Project (conception and execution) Statistical

analysis (Design, Execution, and Critique), Manuscript (Cri-tique): Ami Bebbington was involved in statistical analysis(Design, Execution, and Critique), Manuscript (Critique);Simon Williams was involved in Research Project (Concep-tion), Statistical Analysis (Execution and Critique),Manuscript (Critique); Peter Jacoby was involved Statisticalanalysis (Execution and Critique), Manuscript (Critique);Walter E Kaufmann was involved Statistical analysis(Critique), Manuscript: (Critique); Helen Leonard wasinvolved in Research Project (conception, organization, andexecution), Statistical Analysis (design and critique), Manu-script (Critique).

REFERENCES

1. Laurvick CL, dei Klerk N, Bower C, et al. Rett syndrome in Aus-tralia: a review of the epidemiology. J Pediatr 2006;148:347–352.

2. Hagberg B, Hanefeld F, Percy A, Skjeldal O. An update on clini-cally applicable diagnostic criteria in Rett syndrome. Commentsto Rett Syndrome Clinical Criteria Consensus Panel Satellite toEuropean Paediatric Neurology Society Meeting, Baden Baden,Germany, 11 September 2001. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2002;6:293–297.

3. Bebbington A, Leonard H, Ben Zeev B, et al. Investigating geno-type-phenotype relationships in Rett syndrome using an interna-tional dataset. Neurology 2008;70:868–875.

4. Neul JL, Fang P, Barrish J, et al. Specific mutations in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 confer different severity in Rett syn-drome. Neurology 2008;70:1313–1321.

5. Oliver C, Murphy G, Crayton L, Corbett J. Self-injurious behav-ior in Rett syndrome: interactions between features of Rett syn-drome and operant conditioning. J Autism Dev Disord 1993;23:91–109.

6. Elian M, Rudolf MD. Observations on hand movements in Rettsyndrome: a pilot study. Acta Neurol Scand 1996;94:212–214.

7. Roane HS, Piazza CC, Sgro GM, Volkert VM, Anderson CM.Analysis of aberrant behaviour associated with Rett syndrome.Disabil Rehabil 2001;23:139–148.

8. Wehmeyer M, Bourland G, Ingram D. An analogue assessmentof hand stereotypies in two cases of Rett syndrome. J IntellectDisabil Res 1993;37(Part 1):95–102.

9. Iwata BA, Dorsey MF, Slifer KJ, Bauman KE, Richman GS. To-ward a functional analysis of self-injury. J Appl Behav Anal1994;27:197–209.

10. Nomura Y, Segawa M. Motor symptoms of the Rett syndrome:abnormal muscle tone, posture, locomotion and stereotypedmovement. Brain Dev 1992;14:S21–S28.

11. Kerr AM, Montague J, Stephenson JB. The hands, and the mind,pre- and post-regression, in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev 1987;9:487–490.

12. Mount RH, Hastings RP, Reilly S, Cass H, Charman T. Behav-ioural and emotional features in Rett syndrome. Disabil Rehabil2001;23:129–138.

13. Colvin L, Fyfe S, Leonard S, et al. Describing the phenotype inRett syndrome using a population database. Arch Dis Child2003;88:38–43.

14. Hagberg B, Witt-Engerstrom I, Opitz JM, Reynolds JF. Rett syn-drome: a suggested staging system for describing impairmentprofile with increasing age towards adolescence. Am J MedGenet A 1986;25:47–59.

15. Temudo T, Oliveira P, Santos M, et al. Stereotypies in Rett syn-drome: analysis of 83 patients with and without detected MECP2mutations. Neurology 2007;68:1183–1187.

16. Fyfe S, Downs J, McIlroy O, et al. Development of a video-based evaluation tool in Rett syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord2007;37:1636–1646.

287HAND STEREOTYPIES IN RETT SYNDROME

Movement Disorders, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2010

17. Leonard H, Bower C. Is the girl with Rett syndrome normal atbirth? Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:115–121.

18. Leonard H, Bower C, English D. The prevalence and incidenceof Rett syndrome in Australia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry1997;6:8–10.

19. Jankovic J. Stereotypies in autistic and other childhood disorders.In: Fernandez-Alvarez E, Arzimanoglou A, Tolosa E, editors.Paediatric movement disorders: progress in understanding. Mon-trouge, France: Editions John Libbey Eurotext; 2005. p 247–260.

20. Downs J, Young D, de Klerk N, et al. The impact of scoliosissurgery on activities of daily living in females with Rett syn-drome. J Ped Orth 2009;29:369–374.

21. Stata. Stata Statistical Software. In: ninth ed. College Station,TX, USA: StataCorp LP; 2005.

22. Evans JC, Archer HL, Colley JP, et al. Early onset seizures andRett-like features associated with mutations in CDKL5. Eur JHum Genet 2005;13:1113–1120.

23. Ariani F, Hayek G, Rondinella D, et al. FOXG1 is responsiblefor the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Am J Hum Genet2008;83:89–93.

24. Cass H, Reilly S, Owen L, et al. Findings from a multidiscipli-nary clinical case series of females with Rett syndrome. DevMed Child Neurol 2003;45:325–337.

25. Roze E, Cochen V, Sangla S, et al. Rett syndrome: an over-looked diagnosis in women with stereotypic hand movements,

psychomotor retardation, Parkinsonism, and dystonia? Mov Dis-ord 2007;22:387–389.

26. Schanen C, Houwink EJ, Dorrani N, et al. Phenotypic manifesta-tions of MECP2 mutations in classical and atypical Rett syn-drome. Am J Med Genet 2004;126A:129–140.

27. Temudo T, Ramos E, Dias K, et al. Movement disorders in Rett syn-drome: an analysis of 60 patients with detected MECP2 mutationand correlation with mutation type. Mov Disord 2008;23:1384–1390.

28. Archer H, Evans J, Leonard H, et al. Correlation between clinicalseverity in patients with Rett syndrome with a p.R168X orp.T158M MECP2 mutation, and the direction and degree of skew-ing of X-chromosome inactivation. J Med Genet 2007;44:148–152.

29. Ben Zeev B, Bebbington A, Ho G, et al. The common BDNFpolymorphism may be a modifier of disease severity in Rett syn-drome. Neurology 2009;72:1242–1247.

30. Thelen E. Rhythmical behavior in infancy: an ethological per-spective. Dev Psychol 1981;17:237–257.

31. Kates WR, Lanham DC, Singer, H.S. Frontal white matter reduc-tions in healthy males with complex stereotypies. Pediatr Neurol2005;32:109–112.

32. Carter JC, Lanham DC, Pham D, Bibat G, Naidu S, KaufmannWE. Selective cerebral volume reduction in Rett syndrome: amultiple-approach MR imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol2008;32:436–441.

288 P. CARTER ET AL.

Movement Disorders, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2010