Steichen Then, Now, and Again: Legacies of an Icon by A. D ...Steichen Then, Now, and Again:...

Transcript of Steichen Then, Now, and Again: Legacies of an Icon by A. D ...Steichen Then, Now, and Again:...

Steichen Then, Now, and Again:

Legacies of an Icon

by A. D. Coleman

Prelude

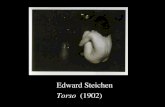

On February 14, 2006, an auction at Sotheby's in New York City set a record for

the highest price ever paid for a single photograph. The image in question, a moonlit

landscape created in 1904, was a complexly handmade object: a platinum print coated

with several layers of gum bichromate, the multiple emulsions and printings giving it a

rich, burnished, distinctive blue-green cast. It stands as a masterpiece of what have

become generically referred to as "alternative processes," an umbrella term covering the

wide variety of formerly obsolescent but now revitalized photographic negative-making

and print-making methods utilized by photographers in the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries.

"The Pond — Moonlight," one of only three known prints of this image, came to

the block with impeccable provenance, deaccessioned from the Metropolitan Museum of

Art in New York, which owns one of the two other variant prints,1 and which acquired this

print by donation from Alfred Stieglitz. Peter MacGill, of New York's Pace/MacGill

Gallery, purchased this nocturne (depicting a scene in then-bucolic Mamaroneck,2 a

town in Westchester County, New York) on behalf of a private collector. The print went

under the hammer for $2,928,000 (including the buyer's premium). That final bid tripled

its estimated sales price — an unprecedented Valentine's Day gift to the medium of

photography.

That this previously little-known and now world-famous print came from the hand

1 The collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York holds the third documented print of this image. 2 Gloria Poccia Pritts, the village historian in Mamaroneck, has proposed that Steichen made the photo while recuperating from typhoid at home of art critic Charles H. Caffin. See Benjamin Genocchio, "GENERATIONS PAST: Hey Mamaroneck, Recognize This Pond?" New York Times, February 26, 2006, Final, Section 14WC, p. 4.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

of Edward Steichen should not surprise us. In tandem with his longtime colleague Alfred

Stieglitz, and on his own after they took separate paths, Steichen continues to loom large

as one of the germinal figures of twentieth-century photography. His career in the

medium spanned three-quarters of the last century; his multiple legacies, generous and

problematic, endure into the new millennium. "The Pond — Moonlight" and the

Pictorialist movement in photography for which it has now become iconic seem as good

a starting point as any for investigating what we have inherited from the man called by

many "the Captain,"3 since that image distills the essence of Pictorialist practice and

represents a highlight of the first phase of Steichen's career.

Movement I: From Pictorialism to Modernism

Because Steichen made this work during the course of his long partnership with

Alfred Stieglitz, and published it first in Camera Work, the journal that Stieglitz edited and

funded, let us begin with that relationship. Steichen's many-sided involvement with his

mentor went well beyond the working relationships with Stieglitz developed by other

members of the Photo-Secession, the loose collective of like-minded Pictorialist

photographers (most of them from the United States) that Stieglitz shepherded for a

number of years.

Steichen initially shared Stieglitz's vision of photography's future, as well as his

proselytizing tendencies. Consequently, he involved himself deeply in Stieglitz's various

projects. They first collaborated on the production of Camera Notes, the short-lived

journal of the Camera Club of New York (1897-1903).4 When Stieglitz resigned from that

organization and the editorship of its journal, Steichen assisted at the birth of an

3 With America's entry into World War II, Steichen, who had served in World War I, once again volunteered for service, this time in the Naval Reserve. Holding the rank of captain, he became head of the U.S. Naval Photographic Institute and commander of all Navy combat photography. Those who worked with him then and thereafter often used that rank as both an honorific and a nickname. For more on his military career, see Christopher Phillips, Steichen at War (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1981). 4 Stieglitz edited all but the last three issues of Camera Notes. For more on this periodical, see Christian A. Peterson, ed., Alfred Stieglitz's Camera Notes (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1993). A facsimile reprint set of the complete journal, supervised by myself, now long out of print, can be found in some research libraries: Camera Notes: The Official Organ of the Camera Club of New York (New York: Da Capo Press, 1977).

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

autonomous periodical, Camera Work (1902-1917), that would operate entirely under

Stieglitz's control.

Steichen designed the cover and other components of this exquisitely produced

journal. It served as the Photo-Secession's house organ and Stieglitz's platform for a

decade and a half. Camera Work's high production values included subtle, delicate,

hand-pulled ink gravures. These prints, from plates sometimes made directly from the

original negatives, proved so sensitive to the nuances of the original prints from which

they derived that, for more than three decades now, they have sold separately in the

market for collectible photographs, considered as, in effect, limited-edition prints of those

works.5

Because Camera Work immediately established itself as the ne plus ultra of

photography publications, those same production values shaped the future of the serious

photography journal as a special type of periodical. The assumption implicit in Camera

Work — that, de facto, such a magazine involved expensive state-of-the-art reproduction

of images — became a given in the field. Subsequent periodicals often sought to

emulate that model. The one that has endured the longest. surviving as a not-for-profit

operation with substantial corporate and foundation support, is Aperture, founded in

1951 by a cluster of major figures in the field who looked consciously to Camera Work as

the desideratum.6 Others have lasted for shorter periods, but some still persist, mostly as

house organs for non-profit organizations and institutions: San Francisco Camerawork,

Katalog (Denmark), Luna Cornea (Mexico), for example.7

The list of "little" photography magazines that have died while striving to imitate

5 The complete illustrations from this journal are collected in Marianne Fulton Margolis, ed., Camera Work: A Pictorial Guide (New York: Dover Publications, 1978), and in Pam Roberts, ed., Camera Work: The Complete Illustrations 1903-1917 (Köln and New York: Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 1997). For a judicious selection of plates and texts, see Jonathan Green, ed., Camera Work: A Critical Anthology (New York: Aperture, 1973). 6 The Swiss magazine Camera (1966-81) — edited by Allan Porter and subsidized by C. J. Bucher Verlag, a Swiss printing and publishing company that used this journal as a showcase for its services — was also modeled on Camera Work, but depended on the patronage inherent in its "house organ" status within that corporate entity. Camera died when the company decided to end its subsidy. However, Bucher did publish 192 issues of the journal before shutting it down. 7 The eponymous San Francisco Camerawork takes its name from a Bay Area organization founded as a photographers' collective, which in turn adopted the term "camerawork" originated by Stieglitz et al to separate their efforts from the various forms of applied photography. Katalog has the Museet for Fotokunst

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

Camera Work stretches from Contemporary Photographer in the 1960s to See in the

1990s.8 Thus, as a model, Camera Work in its physical form has proved problematic. For

every variant that has survived — Aperture, 21st9 — one can point to dozens of failures,

some of them disastrous, as editorial aspirations outstripped fiscal common sense.10

Nonetheless, notably, the physical model established by Steichen and Stieglitz has

remained seductive and magnetic from the moment of Camera Work's debut through the

present. In the minds of many, it continues to define the high-end photography journal,

even well into the digital era.

Camera Work manifests a second level of ongoing influence, in the area of

content. It seems reasonable to propose that Camera Work constitutes the first true

critical journal in photography. The magazine included no tutorial material on

photographic craft and only a modicum of technical discussion; most of its texts were

polemics, profiles, interviews, reviews, and other forms of commentary. In addition to

offering regular contributions from Stieglitz himself, and periodic ones from other

Photo-Secessionists, it served as a frequent platform for two prominent art critics who

were not themselves photographers, Charles H. Caffin and Sadakichi Hartmann.

Moreover, it functioned as a vehicle for occasional texts from other writers — poets,

novelists, playwrights — who elected to address the medium of photography or other

subjects the editors considered relevant.

And, in terms of both the images it reproduced and the essays it presented,

in Odense, Denmark as its sponsor. Luna Cornea comes from the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City. 8 The first successful attempt to break the mold came with Afterimage, founded by Nathan Lyons in 1971 as the house organ of the Visual Studies Workshops (VSW) in Rochester, New York, and still running. Subsidized also through grants and other revenues available to the VSW as a non-profit organization, Afterimage has served as a vehicle for student writing as well as work by professionals in the field. The reproductions therein are single-run halftones that do not attempt to match the richness of the originals, included simply as referents. Views: A New England Journal of Photography, based at the Photographic Resource Center (PRC) in Boston and founded in 1979 by this author, was a later attempt to follow a different path than the one proposed by Camera Work. 9 While embracing Camera Work as a precursor, 21st (an annual) defines itself as a limited-edition book, not as a periodical, thus presenting itself to potential purchasers with a much different marketing strategy. 10 For example, one can trace the collapse of the San Francisco–based Friends of Photography in the 1990s in part to the financial failure of its journal, titled See, inaugurated by Andy Grundberg, then the FOP's director. The journal's high production values were not sustainable by its low subscriber base. The FOP (founded by Ansel Adams in 1967) never recovered from that crisis, and ceased all operations officially on October 31, 2001.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

Camera Work sought to position itself, and the medium to which it was devoted, within

the larger context of creative activity in all the art forms of its time. Thus, unlike virtually

all previous photography journals (and unlike most since then), it did not target amateur

and professional photographers as its exclusive or even primary audiences. Instead, it

sought to appeal to a broader audience for discourse about the cultural issues of its

day.11

Steichen did not generate much of that textual content himself, though he did

contribute several pieces of writing. But responses to him and his work appeared in

those pages regularly, as did his images.12 Perhaps more important, he served Stieglitz

as a pipeline to the European branch of modernism.13 Many images by the European

photo-pictorialists — plus paintings, drawings, and other works by such major figures in

European art as Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and

Constantin Brancusi — that first came to the U.S. via Camera Work , got there through

Steichen. So did texts by Gertrude Stein, Maurice Maeterlinck, and other Europeans and

Europe-based U.S. expatriates that appeared in the magazine. Thus, as a

behind-the-scenes "finder" for the Camera Work project, Steichen also helped to

establish the concept of the critical journal in photography as one that considered the

medium in relation to work in other media, taking the most expansive and encompassing

approach to the field of ideas that the discourse around photography could address.

The same works that Steichen located in Europe for the pages of Camera Work

often ended up in exhibitions held at the Little Galleries of the Photo Secession14 that

Stieglitz ran in Manhattan. (Steichen's own prints frequently graced those walls as well.)

11 Here again, one can find journals that would later follow that example: DoubleTake (most recently reincarnated as DoubleTake/Points of Entry), forinstance, which has a particular concern with the intersection of photography and contemporary literature. Coming to the same juncture from the other direction, more than a few "little" literary magazines today combine creative writing with photography, a practice that goes back to the 1950s and '60s and such magazines as Choice and Evergreen Review. 12 Ronald J. Gedrim writes, "Steichen's work was reproduced 68 times [in Camera Work], more frequently than [that of] any other contributor to the journal." See "An Art for Life's Sake," in Gedrim, ed., Edward Steichen: Selected Texts and Bibliography (Oxford: ABC-CLIO Ltd., 1996), p. 10. This included several "Steichen Numbers" of the journal, and a special "Steichen Supplement" in 1906. 13 Born in Luxembourg in 1879, Steichen returned to Europe in 1900 and lived there for much of the time until 1923, when he reestablished residence in the U.S. 14 The gallery also became known as "291," from the street address, 291 Fifth Avenue.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

Initially the galleries occupied a rental unit vacated in 1905 by Steichen, who promptly

collaborated with Stieglitz on redesigning it as a suite of exhibition rooms. They

visualized this environment as a decisive break with the floor-to-ceiling jumble of

elaborately framed works set amid velvet curtains, faux-Greek pedestals, and other

decorative trappings then typical of salon-style presentations of works of visual art.

These new spaces remained clean and spare, free of extraneous decor, painted in white

or neutral colors interspersed with burlap-covered panels, with the works on display

framed minimally and given breathing space between themselves, either clustered in

small groupings or run in a single line at eye level around the walls.

As Olivier Lugon argues elsewhere in this book, this represents the emergence of

the modernist vision of the gallery as a quasi-sacred, meditative space, the

presentational format that, decades later, Brian O'Doherty would dub "the white cube"15

and propose as a central facet of the modernist project. Here we have the white cube's

precise point of origin: spaces designed by Stieglitz and Steichen for the display of

photographs, modernist artworks in various media, African sculpture, and more.16

This marks Steichen's first powerful influence on the presentation of photography

— and, more broadly, works of art in all media — in public spaces. The prototypical

"white cube" environment that he and Stieglitz initiated came to pervade the art world,

not just in galleries but in museums as well. It continues today as the dominant

assumption in the design and architecture of display spaces for all forms of art.

Movement II: Into the Mainstream

Photographers in our day take for granted the option of moving between projects

of their own devising (often self-supported) and various forms of bespoke or

15 "The history of modernism is intimately framed by [the gallery] space." Brian O'Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (San Francisco: The Lapis Press, 1986), p. 14. In his otherwise lucid argument O'Doherty regrettably does not trace the origins and evolution of the "white cube" as an idea. Instead, with only the briefest stops at Kurt Schwitters' "Merzbau" and several Marcel Duchamp installations, he leaps from the late 19th century, with its salon-style painting displays, to the 1960s artworld. 16 Stieglitz elaborated on that model in his subsequent gallery projects: the Anderson Galleries, 1921–25; The Intimate Gallery, 1925–29; and An American Place, 1929–46)

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

commissioned work. Those include editorial imagery, advertising imagery, still

photography for commercial films, illustrations for corporate annual reports, studio

portraiture, and many other variants of applied or functional photography. This has

become so commonplace that it goes largely unremarked as a phenomenon. The list of

photographers who have supported themselves and subsidized their more passionate

creative commitments in these ways goes far back, in a lineage that runs from William

Wegman, Sarah Moon, and Duane Michals today back through Diane Arbus and

Richard Avedon in the post-World War II years to Lisette Model, André Kertèsz, Edward

Weston, and Man Ray in the first half of the last century.

Many think that tendency begins with Edward Steichen. In fact, however, more

than a few notable photographers before him, such as Mathew Brady in the second half

of the 19th century and William Henry Jackson well into the 20th century, had sustained

their creative efforts by soliciting clients for studio portraits, by licensing reproduction

rights to their images for mass distribution, or by other commercial applications of their

talents. Steichen's name has become closely associated with this practice because, in

his instance, the decision to undertake such work — and, more important, to endorse it

publicly and justify it unapologetically — sparked a substantial controversy within the

microcosm of the photography world at the time.

Steichen produced his first portraits on assignment — studies of Theodore

Roosevelt and William Howard Taft — for Everybody's Magazine in 1908. The designer

Paul Poiret commissioned his first fashion photographs in 1911. By 1923 Steichen had

begun working for the J. Walter Thompson Company, a New York-based advertising

agency, while also serving as Chief Photographer for Condé Nast Publications. His

efforts in this territory went well beyond the mere provision of images on demand. Aside

from contributing the strength of his own photographic style, Steichen had considerable

input into layout, design, and other aspects of the presentation of his own images (and

those of others) on the printed page.

This decision to move into the terrain of "useful" photographic imagery,17 and to

17 Steichen applied the term "useful" to his photographic concerns in an interview with this author at his West Redding, Connecticut, home on 7 July 1969. He was then ninety years old. The interview was published as "Steichen and the Bunch at 291," Photograph 1:2 (November 1976), pp. 1–3. This idea received further exploration in my essay, "The 'Useful' Photographs of Edward Steichen," Photoshow 2,

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

prioritize imagery that would reach its audience through the vehicle of ink reproduction

on the printed page of mass-circulation periodicals, struck many of Steichen's former

colleagues (including Stieglitz) as a betrayal of the principles on which the

Photo-Secession had been founded.18 It also marked the beginning of Steichen's gradual

abandonment of the hand-worked "alternative process" approach to printmaking, in favor

of a less elaborate (though no less carefully nuanced) involvement with gelatin-silver

paper as a vehicle,19 and his more abrupt leaving behind of the painterly visual style of

most pictorialism,20 replaced by a hard-edged, sharp-focused approach to photographic

picture-making.

These new methods became defining markers of photographic modernism (the

U.S. version thereof in particular21). We can see Steichen exploring this approach as

early as "Heavy Roses," from 1914, and "Lotus," from 1915. He would continue to

employ assorted pictorialist tropes for another decade (see, for example, "Dana and the

Orb" from 1923). And he would use the more hand-worked processes for awhile longer

as well. The print of "Dana and the Orb" in the collection of the George Eastman House

is a platinum and ferro-prussiate print; the Museum of Modern Art in New York has a

1921 "Harmonica Riddle" in palladium. But by the middle 1920s Steichen's involvement

with the "alternative processes" of photography had become marginal. Thereafter he

would experiment with new materials as they emerged (notably color films and papers),22

1:2 (May–June 1980), no page. We should note that while many of the Photo-Secessionists, including Stieglitz, Robert Demachy, and F. Holland Day, were independently wealthy and did not need to work for a living or make money to support their photography, others did, Steichen among them. 18 For an account of the resulting "firestorm of protest in the art community," see Gedrim, op. cit., pp. 1-2. 19 Platinum had wartime uses, so commercially produced platinum paper, previously available, became scarce with the onset of World War I. By the end of that conflict most of the processes and materials favored by the pictorialists had begun to fall out of fashion and become hard to find. Both European and American modernists relied almost exclusively on gelatin-silver paper as the primary vehicle for their printmaking, sometimes employing selenium and other toning chemicals in the processing of prints. 20 Famously, Steichen burned all his paintings in France in mid-1921, turning his attention exclusively to photography. He had been formally educated as a painter and lithographer, and had worked in both photography and painting until then. 21 European modernism embraced with open arms many forms of photographic picture-making anathematized by modernism in the U.S. To name just a few: solarization, photomontage, photocollage, the photogram. While Steichen explored one or two of these himself, none at length, he remained open to them in his eventual role as a curator — though mostly accepting of such work when it came from Europeans, not from Americans. 22 Steichen's experimentation with color processes merits more than this footnote. That exploration began

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

but would not devote further effort to pursuing the earlier printmaking techniques of his

medium.

Well ahead of many, then, Steichen understood and adopted a modernist position

in his own picture-making. He began to work in the approach that in Europe would

become known as the "New Objectivity" (Neue Sachlichkeit). In the States, that tendency

would get dubbed "purism" by devotees of the Group f.64 in which such figures as

Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Imogen Cunningham joined, and would be referred

to as "straight photography" by others who favored it. As modernism emerged in his

medium, Steichen set aside some previous photographers' attempts (including his own)

to position the medium among the fine arts through labor-intensive production of

hand-crafted objects that could lay some claim to what Walter Benjamin would later

describe as the "aura" of unique handcrafted works of art, and moved away from such

efforts by his contemporaries. Instead, he plunged himself into what Benjamin

memorably named the "age of mechanical reproduction," embracing that phenomenon

wholeheartedly and exploring its possibilities. More than a decade before Benjamin

issued his now-famous hypotheses, therefore, Steichen was operating according to the

principles that Benjamin would subsequently articulate.23

In doing so, Steichen established as respectable a photographer's decision to

move at will between the gallery wall and the printed page of newsstand magazines as

with his early training in lithography and chromolithography, and his work as a painter; continued with his investigation of gum-bichromate and other "alternative processes," and his pioneering work with the short-lived Autochrome process; and lasted throughout his career as both a commercial and a creative photographer, manifesting itself in experiments to see what he could achieve with such subsequent technologies as dye transfer, carbro, and Kodachrome. It is safe to say of Steichen, as of few if any others, that from the beginning of his work as a photographer to his retirement from picture-making he investigated every available option for color photography, and created fully resolved works in almost all of them. This makes him extremely untypical of modernist photographers, most of whom worked exclusively in black & white. Here again Steichen seemed to have anticipated an evolutionary moment in the medium, that of the emergence of new color systems in the 1970s and the eventual dominance of color in all forms of photographic practice, whether applied or artistic. 23 Benjamin based his ideas in part on his encounters with photographs such as Steichen's, printed in ink in large editions in mass-circulation periodicals belonging to what was then generically referred to as the "picture press." Benjamin anticipated that such replication of images in the form of indistinguishable copies would demystify imagery itself in ways he proposed would prove revolutionary ― both socially and culturally progressive. See Benjamin's 1936 essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" in the collection Illuminations, Hannah Arendt, ed., translated by Harry Zohn (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1968), pp. 217-51.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

vehicles for imagery. He thereby enhanced the credibility of the photographer who

switches readily between personal/creative projects and commercial/applied

commissions. His example of cross-pollination would stand subsequent generations of

working photographers in good stead. By now the issue has lost its controversial edge.

But it remains a subject of debate, with proponents of strong conviction on each side. In

the event, the ranks of photographers with feet in both camps have swelled continuously,

including ever more with serious credentials in creative photography. As a result, the

skepticism that once attached to such dual allegiances has long since evaporated.

Movement III: Peacetime to Warfare

During World War I Steichen had served in the Allied forces, pioneering aerial

photography and the analysis thereof.24 (His siding with France contributed to the schism

between himself and Stieglitz, who supported Germany.) In World War II Steichen took

on another role, becoming what we would now call "embedded." Volunteering his

services, he worked for the U.S. Navy as a filmmaker, documentary photographer, and

photojournalist, while heading up a handpicked team of photographers25 generating

imagery intended as unequivocally supportive of the Allied Forces and pro-U.S. in

particular.

Photographers covering that war generally operated on the sufferance of the

military; access to combat zones and other newsworthy situations required passes and

other forms of approval from the relevant chains of command. The photographers' output

(like that of most journalists) usually underwent rigorous censorship, if not immediately

by military offices set up for that purpose then by editors back home operating under

strict guidelines imposed by the armed forces. Thus "shooting the war" necessarily

involved cooperating with the chain of command of one side or the other and submitting

one's imagery and written stories and captions to a censorial process, a fact taken for

24 When the United States entered World War I, Steichen volunteered for military service (1917). Commissioned as a first lieutenant, he became a technical advisor specializing in aerial photography. Appointed as head of the newly independent Air Service division of the Army Signal Corps' Photographic Section, Steichen oversaw 55 officers, 1000 enlisted men, and five squadrons of photo-surveillance planes.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

granted by such staff and freelance photojournalists as Margaret Bourke-White, W.

Eugene Smith, Lee Miller, Robert Capa, and countless others working on assignment in

that era.26

In addition to photographers like those, employed by the various press services,

periodicals, and picture agencies, all branches of the U.S. military had their own

photographic and film divisions, staffed with enlistees and draftees. Steichen organized

and commanded such a unit. This willing embedding of himself anticipates the practice

that would become widespread with the onset of "Operation Iraqi Freedom" in March

2003. Controversial now, due to doubts over the latitude allowed to embedded

photographers and the potential biasing of and restrictions on their documentation that

such involvement could generate, it was not considered suspect to any notable degree in

photography or journalism circles at the time Steichen undertook that project.

His own photographic output during the war and that of his team, widely circulated

by the Navy press service, appeared in countless publications internationally, as

individual images and clusters thereof. In addition to that, Steichen himself supervised

the creation of several large-scale projects drawn from this ever-growing collective

archive of war-related material. These included:

* the exhibition and book version27 of "Road to Victory" (the show premiered in

1942 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, with accompanying text by Carl Sandburg

and exhibition design by Herbert Bayer);

* the film The Fighting Lady, a U.S. Navy-sponsored documentary titled after the

nickname of the aircraft carrier that served as home base for Steichen and his team

(released in 1944, directed by William Wyler, the film's production was supervised by

25 See note 3. 26 For more on this, see Michael S. Sweeney, Secrets of Victory: The Office of Censorship and the American Press and Radio in World War II (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2001). In his autobiography, Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), John G. Morris provides a look at this process from the standpoint of one who worked as a picture editor during that conflagration. See pp. 53-99. 27 Published as U.S. Camera 1943 (New York: U.S. Camera Publishing, 1942). Steichen and the editor of U.S. Camera, Tom Maloney, forged a close alliance during those years. U.S. Camera issued a monthly newsstand edition of a magazine and an annual hardbound survey of photographic work in different modes.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

Steichen, who also generated all of the full-color cinematography used in it);28

* the exhibition and catalogue Power in the Pacific: Battle Photographs of Our

Navy in Action on the Sea and in the Sky (which premiered at MoMA in 1945);29

* and the book U.S. Navy War Photographs: Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Harbor (1946,

sponsored by the U.S. Navy).30

Steichen had orchestrated previous publications and exhibitions of work by

himself and others, but never on this scale. These wartime projects reached larger, more

far-flung, and more diverse audiences than anything under his absolute editorial control

that he had attempted until then. They departed radically from the determinedly elitist,

small-circulation journal Camera Work, the rarefied environment of the

Photo-Secession's "Little Galleries," and other vehicles intended for the display of

photographs as precious objects, and they obviated the making of photographs

specifically conceived and created for such display.

These World War II productions took an unabashedly populist stance on every

level, from purchase price to distribution to accessibility of content to intended audience

size. Steichen's high-profile activity during this war not only established the public

precedent of the voluntarily embedded photojournalist in wartime but pointed him toward

usages of the thematic group statement in photography as a vehicle for mass

communication and a means of persuasion. In short, this experience with the

28 Steichen's subsequent book The Blue Ghost: A Photographic Log and Personal Narrative of the Aircraft Carrier U.S.S. "Lexington" in Combat Operation (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1947) was effectively a book version of The Fighting Lady. 29 After its MoMA debut, this exhibition traveled nationally, beginning at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut. (For a glowing review of the touring version see Anonymous, "Art: Closeup of War," Time, April 23, 1945, p. 1.) Subsequent venues included the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, December 6-26, 1945, under the title "Naval Power in the Pacific: Combat Photographs compiled by Capt. Edward J. Steichen, U.S.N.R." The book version, Power in the Pacific: Official U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Photographs Exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York ― A Pictorial Record of Navy Combat Operations on Land, Sea, and in the Sky, first came out as a Museum of Modern Art exhibition catalogue (New York: Wm. E. Rudge's Sons, 1945), "compiled and with a foreword by Edward Steichen." U.S. Camera subsequently published an expanded version as the 1945 edition of its annual, under the title Power in the Pacific: A Navy Picture Record (New York: U.S. Camera Publishing, 1945). 30 US NAVY WAR PHOTOGRAPHS: Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Harbor, "compiled" by Captain Edward Steichen (New York: U.S. Camera, n.d., circa 1946). Subsequently reprinted twice, in 1956 and 1980, by Crown Publishers in New York, and again in 1987 by Random House. Phillips notes that this book was initially produced in an edition of six million copies, priced at 35 cents each. (Steichen at War, p. 45.)

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

propagandistic potential of his medium gave Steichen tangible proof that his

photography and that of others could serve not only to materialize "a way of seeing"31 but

also to promote a particular point of view.

Movement IV: Maker Turned Impresario

Nowadays the large-scale thematic group show and/or book is a commonplace,

not only in photography but in all the visual arts. So, too, is the blockbuster traveling

museum exhibition. When we trace such ambitious — and, in the minds of some,

grandiose — undertakings to their origin, one enterprise signals (more than any

preceding it) the introduction of this type of project into the international circulation of art

in general and photographs in particular: The Family of Man, Steichen's liberal-humanist

magnum opus, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art in January of 1955.

By then Steichen had become entrenched as the Director of the Department of

Photography at MoMA, a position he assumed in 1947, a platform that historian

Christopher Phillips has called "the judgment seat of photography"32 and that this author

has described as "unquestionably the single most influential sponsorial position in

contemporary creative photography."33 Steichen's appointment to that position over the

head of Beaumont Newhall added yet another layer of contention to the Captain's

career.34

31 This phrase, applied by James Agee to the street photography of Helen Levitt, became commonly used to specify a photographer's distinctive vision or style. See Agee's foreword, "A Way of Seeing," in Helen Levitt, A Way of Seeing (New York: Viking Press, 1965), pp. 3-8, 73-78. Presumably John Berger's 1972 BBC film series Ways of Seeing (subsequently turned into a widely distributed book) responded in part to that concept. 32 Christopher Phillips, "The Judgment Seat of Photography," October 22 (Fall 1982), pp. 27-63. Since publishing this essay, Phillips himself has taken on a curatorial role at the International Center of Photography in New York City. 33 See my essay, "On the Subject of John Szarkowski," Picture, No. 8, 1978, no page. Reprinted in my book Light Readings: A Photography Critic's Writings, 1968-1978, second edition, revised and expanded (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), pp. 287-294. Starting in the early 1980s the previously hegemonic influence of MoMA's Department of Photography began to wane; neither Philips' description nor my own from that period fits today. 34 For more on this see my essay, "The Impact on Photography: 'No Other Institution Even Comes Close,'" ARTnews 78:8 (October 1979; Museum of Modern Art Fiftieth Anniversary Issue), pp. 102–5. Reprinted as "Photography at MoMA: A Brief History" in my book Tarnished Silver: After the Photo Boom, Essays and

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

Steichen's entry into full-time museum curatorship seems in retrospect both

inevitable and inevitably controversial. But Steichen had proved himself a subject of

dispute well beyond photo-world circles even before taking over the MoMA department.

He and the issues he represented in the mid-'40s were considered of broad enough

interest to warrant a skeptical, often acidulous two-part profile by Matthew Josephson in

the influential periodical The New Yorker in 1944.35

Nor did the dispute over his arrival at MoMA restrict itself to issues of

photographic esthetics, or to the MoMA administration's disregard of Newhall's tacit prior

claim on that position. Steichen's plans for his MoMA position included the raising of

$100,000 from ten manufacturers of photography equipment to subsidize his own salary

― the first time that commercial/corporate monies had entered the museum in such a

fashion. This set another precedent that has turned into a commonplace in the museum

world, albeit one hotly debated at the time and far from resolved today.

Ultimately, however, the uproar centered on the direction Steichen's detractors

assumed the department's exhibition policy would take under his leadership. In the years

leading up to his resignation from MoMA, Beaumont Newhall, Steichen's predecessor,

had positioned himself (and was seen by the photography community) as the champion

of the "purist" or "straight" lineage that presumably ran from the Scottish team of David

Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson through Eug� ène Atget to Stieglitz and thence to

Walker Evans, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams. The faction within the

photo world that endorsed this vision of the medium's evolution viewed Steichen, with his

populist tendencies and track record in the fields of commercial and applied

photography, as a traducer of that photography-for-photography's-sake tradition.

From their perspective, Steichen had long since revealed himself as a renegade

who would doubtless skew the department's exhibitions36 toward functional photography

Lectures 1979-1989 (Midmarch Arts Press, 1996), pp. 98-106. 35 Matthew Josephson, "Commander With A Camera — I," The New Yorker 20:16, June 10, 1944, pp. 30-34ff., and "Commander With A Camera — II," The New Yorker 20:17, June 17, 1944, pp. 29-32ff. 36 Publications issued by this MoMA department up till then had been few, far between, and small, with the exception of Newhall's hugely influential survey, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949). First issued in 1937 as the illustrated catalog of the exhibition 'Photography, 1939-1937' organized by Newhall for the Museum of Modern Art in 1937, this book was reprinted in 1938, with minor revisions, and issued by MoMA as Photography: A Short Critical History.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

— fashion, photojournalism, illustrational work, and the like — and away from the

creative and documentary end of the spectrum. Characteristically, in the uproar following

the announcement of his MoMA appointment, Ansel Adams (of all the Group f.64

members the one closest to Newhall both professionally and personally37) excoriated

Steichen as "the anti-Christ of photography: clever, sharp, self-promoting and

materialistic."38

Yet if one compares the photographers, the images, and the types of work that

Steichen elected to show during his tenure at MoMA (which lasted till 1962) with what

Newhall had already shown there (1940-47)39 during his own MoMA stint and later chose

to show at the George Eastman House in Rochester, his next and final curatorial

appointment (1948-71),40 the overlap is almost perfect.41 Moreover, within the

architectural limitations of the MoMA photo gallery and the other MoMA spaces to which

Steichen (and Newhall before him) had periodic access, on the one hand, and those of

the Eastman House spaces under Newhall's supervision on the other, one can say that

both curators applied the same "white cube" approach to the large majority of shows

under their control. In short, the differences between their separate and independent

overviews of the medium, and their approaches to the museum presentation thereof,

seem negligible, at least in retrospect.

The major exception, of course, would be Steichen's chef-d'oeuvre, The Family of

Reconfigured more extensively, the 1949 version became the standard reference work on the medium's history in English. In the time period under consideration here it was widely understood as such internationally. 37 And the one most involved in the MoMA department's founding. See Coleman, "The Impact on Photography," loc. cit. 38 Quoted in Russell Lynes' delightfully irreverent "unauthorized biography" of MoMA, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Atheneum, 1973), p. 259. Lynes, who provides a juicily detailed account of the whole affair, paints Steichen's role as that of a self-serving, power-hungry ogre. 39 Like Steichen, Newhall mounted shows at MoMA before his curatorial appointment. Newhall began his MoMA career as librarian, and organized shows there from 1937 on. 40 Newhall served as curator of the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House from 1948 to 1958, then its director from 1958 to 1971. The institution changed its name from the George Eastman House to the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House during his tenure. 41 No evidence suggests that Steichen made any of his curatorial choices in order to placate those who formed his opposition. To the contrary, all those decisions seemed consistent with his clearly enunciated broad overview of the medium's history and current situation.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

Man, an ambitious experiment that one cannot imagine Newhall either conceiving or

undertaking.42 Applying a combination of picture-press layout methods and innovative

exhibition design ideas in collaboration with architect Paul Rudolph, choosing and

juxtaposing and scaling images according to his own editorial decisions, Steichen

ignored what were then already standard methods for display of photographs as objects

of art.43 In so doing, he created what we would now call an installation — and a massive

one at that, utilizing 503 pictures by 273 photographers from 68 countries. With that act

he and his project team moved the museum display of photography decisively from

exhibition to spectacle.

Had this vast survey simply enjoyed its scheduled run at MoMA, where it broke all

attendance records, viewed there by tens of thousands of New Yorkers and visitors to

the city, The Family of Man would have made a considerable mark on the field by

demonstrating to museum directors around the world the drawing power of spectacular

exhibitions of photography.44 But Steichen and his colleagues had planned a widespread

dissemination of the project, which they achieved.

Much of The Family of Man's lasting influence resulted from Steichen's application

of lessons in the distribution of imagery and ideas that he'd gleaned from his several

wartime projects. But this extravaganza's reach exceeded those prior efforts by far. The

exhibition only began its life at MoMA, on West 53rd Street in Manhattan. Produced in

multiple copies, the show traveled internationally for years, touring for seven years in

42 We should also not forget Steichen's several curatorial warm-ups to The Family of Man: "Korea: The Impact of War in Photographs" and "Memorable LIFE Photographs" (both 1951). 43 Steichen actually had photographers lend their negatives to the museum in order to generate new custom-made prints precisely sized to the layout of the planned display. Some images even underwent re-cropping to adjust them in their relation to other images (Gedrim, op. cit., p. 49). The resulting borderless prints were mounted on masonite with wheat paste (ibid., p. 61). This emulsification of the print-as-object, a technique already established by Steichen in the wartime shows he had created, specifically overrode the formula for the presentation of creative and documentary photography established by Steichen himself and Stieglitz in the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, then adopted by Newhall and others as a signal of respect for the autonomy of the photographer's individual vision and his or her particular relationship to the print-maker's craft. Barbara Kruger and other postmodernists would build on Steichen's example in the installation work of the postmodern period. 44 For a discussion of its specifically museological consequences, see Mary Anne Staniszewski, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998), which provides a larger analysis of MoMA's cultural and exhibition policies.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

multiple sets throughout 38 countries.45 An estimated nine million people attended those

various showings into the 1960s.46

The show inevitably partook of (and consciously took part in) the ideological

struggles of the Cold War. Prominently displayed at the American National Exhibition in

Moscow in 1959, the site of the famous "kitchen debate" between Soviet premier Nikita

Khrushchev and U.S. Vice-president Richard M. Nixon, The Family of Man contributed to

a perception of the United States as a functioning, thriving democracy, an "open society,"

in Karl Popper's term, as distinct from the barred and gated nations of eastern Europe

and the U.S.S.R's then-ally, China.47

The Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, already famous in the Soviet Union,

attended the show, where he met both Steichen (who made his portrait later on that trip)

and his brother-in-law, Carl Sandburg. Yevtushenko still recalls the power of that

exhibition in that particular place at that historical moment: "So many Muscovites lined

up for that exhibition — thousands, every day. Maybe especially those from our

generation, my generation. [He was born in 1933.] My friends and I were all dreaming of

Russia again being part of the common civilization. We didn't feel completely lost or

culturally isolated; we had some great Western books, French, American, English books

in translation. And we were brought up to understand Russian culture as a part of

European culture. But we wanted some sense of physical connection with the rest of the

world, some feeling of contact. This great show gave us that. It was a revelation."48

45 For a comprehensive history of this project, see Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995). According to Sandeen, four complete sets, including the one originally mounted at MoMA, toured abroad under the auspices of the United States Information Agency. Two smaller versions produced by MoMA traveled throughout the U.S. And a Japanese publishing house produced three more sets — one full, two partial — "from negatives furnished by the museum." See Sandeen, pp. 95-96. Sandeen also notes that the USIA produced two films based on The Family of Man, the first a four-and-a-half-minute introduction to the show, the second a 26-minute filmic version of the show. The USIA subsidized and circulated 300 prints of the latter, almost two-thirds of them dubbed into 22 languages. Screenings of these films took place in over 70 overseas countries. See Sandeen, pp. 96-97. 46 Sandeen, op. cit., p. 95. 47 A survey of contemporary painting from the U.S. was also included in this "American National Exhibition." 48 In conversation with the author, October 20, 2006, Nimrod Awards Conference, University of Tulsa, Oklahoma. In 1983 Yevtushenko published Invisible Threads (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company), a collection of his own photographs and poems; in the introduction he credits The Family of Man as its

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

The Family of Man also found itself subject to internal as well as external political

considerations. Eric J. Sandeen has pointed out that a centrally placed and chilling

image that appeared in all the exhibition versions — a 6x8' back-lit color transparency of

a hydrogen bomb test — did not find its way into the book version. He proposes that this

resulted from self-censorship on Steichen's part rather than from pressure from the

publishers or other parties.49

The book version of The Family of Man came out in at least four separate forms:

hardbound, fancy softcover, cheaper softcover, and pocket-sized paperback.50 The book

remains in print more than half a century after its first release, and it endures as the

single book of photographs most likely familiar worldwide to someone not otherwise

concerned with the medium. With millions of copies in circulation, it stands as the longest

continuously published book in the medium's history.

Nor has the final curtain rung down on the exhibition. In 1993 one of the traveling

versions of The Family of Man, lovingly restored, opened to a new generation of viewers

in Toulouse, France, then went on to Tokyo and Hiroshima, Japan, before returning to

Europe in 1994 for permanent installation in a specially designed museum space in the

Château de Clervaux, Luxembourg — the only photography exhibition to date ever so

honored anywhere.51 This site is now inscribed on UNESCO's "Memory of the World"

register.52 It is almost impossible to calculate the number of people worldwide who have

encountered this project of Steichen's in one or another of its forms. And that number

inspiration. 49 Sandeen, op. cit., p. 48, 64-68, and elsewhere. 50 According to Sandeen, "The USIA distributed magazine-format previews of the exhibit in advance of each showing." (P. 96.) Thus a mini-version of the book also found its way into mass circulation. In one form or another, the exhibition layouts by Steichen and Rudolph and the book design and page layouts by Steichen and Leo Lionni achieved an unprecedented level of market saturation, multipurposed in many different formats and media. Aside from the publications, films, and other versions of the project authorized by Steichen and MoMA, the show and book found their way into the culture as reference points through news stories, reviews, and other commentary in the media. Features on the show appeared in large quantities in the print media, as well as in newsreels, on TV, etc. No previous exhibition of art or photography had received comparable coverage in the media. 51 In 1964, at the end of the collection's journey around the world, the American government gave this set as a present to the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, in recognition of Steichen's significance there as a native son. 52 One can find further details of the restoration project, and take a "virtual tour" of the permanent

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

increases daily.

Controversial even during its prenatal phase, since its public birth The Family of

Man has sparked a subsequent half-century's worth of argument and research.

Photographer, teacher, and editor Minor White would publish a critique of The Family of

Man in Aperture53 that attacked Steichen for decontextualizing individual images from

photographers' bodies of work in order to reshape their meaning to suit himself.54 Roland

Barthes gave it a pithy semiological pummeling upon the occasion of its arrival in Paris.55

Commentators from Jacques Barzun to Susan Sontag show up on the list of those who

have felt the need to respond to this venture, pro and con, in the decades since its

emergence. So that controversy has not ended: witness the publication of recent books

and essays on this subject, evidence of the enduring potency of Steichen's culminating

effort.56

The Family of Man remains a reference point and subject of animated debate.

This is not due to dispute over the relative merits of the photographers included (many of

whom have become canonical, all of whom have entered the history books, at least as

footnotes), nor does it stem from disagreement over the relative value of the particular

images chosen to compose it. The argument revolves around the specific curatorial

concept used to organize the show — its sociopolitical message, its theme of

transnational and transcultural human solidarity — and, more broadly, the curatorial

power of image contextualization that it demonstrates so vividly.

installation, at http://www.luxembourg.co.uk/clervaux.html. 53 Minor White, unsigned editorial, "The Controversial Family of Man," Aperture 3, 1955, pp. 8-27. It should be noted that Aperture's founders constituted a veritable who's who of Steichen's main opponents in photography, starting with Beaumont and Nancy Newhall and Ansel Adams. 54 Oddly enough, White would later curate large group shows in which he committed the same sins, and for which this author criticized him in print on grounds remarkably similar to those White had used in chastising Steichen two decades earlier. See my essay "Sticky-Sweet Hour Of Prayer," Village Voice 18:11 (15 March 1973), p. 24. Subsequently reprinted — along with the unpublished second half of this critique — in my book Light Readings: A Photography Critics's Writings, i968-1978 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979; second edition, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), pp. 140-50. 55 Roland Barthes, "The Great Family of Man," Mythologies (New York: Hill & Wang, 1975), pp. 100-102. Translated by Annette Lavers. 56 E.g., Lili Corbus Bezner, Photography and Politics in America: From the New Deal into the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), pp. 121-74. The journal History of Photography recently devoted an entire issue (Winter 2005) to The Family of Man. See also Sandeen, op. cit.

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

Other projects of Steichen's aside from The Family of Man still resonate. In 1972

theorist Allan Sekula provided a dissection of the entry into the art market of "vintage"

prints of Steichen's World War I aerial photographs for the military.57 In 1991, under the

auspices of MoMA's "Projects Room" series, artist Dennis Adams' show "consisted of

site-specific installation work including a chain of hand-crafted vitrines, wall-size

photographs of MoMA's 'Road to Victory' exhibition from 1942."58 And now a print of

Steichen's, made at the beginning of the last century, has set a new high price for

photographs at auction. More than four decades after he largely retired from public life,

and more than three decades after his death, Edward Steichen remains very much with

us — perhaps more so, and in more ways, than at any time since he left the Museum of

Modern Art.

Finale

Take your choice, then. We have Steichen as print-maker extraordinaire, ultimate

vindicator of what Lyle Rexer has dubbed "the antiquarian avant-garde."59 We have

Steichen as co-inventor of the critical journal and "little magazine" of photography. We

have him as co-designer of "the white cube," the prototypical art-display space of

modernism. We have him as introducer of European modern art to the U.S. We have him

as adroit, pathbreaking navigator between the realms of creative photography and

applied photography, including advertising, editorial, military, and wartime propaganda.

We have him as curator of the most powerful museum department of photography of his

era. We have him as pioneer of the museum exhibition as installation. We have him as

advocate of the didactic, thematic group exhibition. And we have him as the organizing

force behind the single most influential and most widely seen internationally traveling

57 See Allan Sekula, "The Instrumental Image: Steichen at War," Artforum XIV:4, December 1975. Subsequently reprinted in Sekula, Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works 1973-1983 (Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1984), pp. 33-52. Sekula denounced an art market capable of turning such images into aestheticized consumer goods. 58 See Marcus Bleyer, "Road to Victory: An Interview with Dennis Adams," from Museo, Spring 2003, a publication of Columbia University, online at http://www.columbia.edu/cu/museo/6/adams/index.html. 59 Lyle Rexer, Photography's Antiquarian Avant-Garde: The New Wave in Old Processes (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002).

Steichen Then, Now, and Again A. D. COLEMAN

museum-scale photography exhibition with accompanying monograph ever created.60

Whichever Steichen you choose, he remains pertinent to virtually every issue

actively debated in photography today. One can approach all of these aspects of

Steichen's cumulative lifelong project in his chosen medium from many different

standpoints.61 I do not intend to make a case for any one of them outweighing the other,

nor to take a position in favor of or against any phase of his work. I think it more valuable

to point out that, taking all his legacies into account, he remains a central figure —

perhaps the central figure — of twentieth-century photography.

The ramifications and influence of Steichen's activities in the field endure. From

the beginning of his life in photography to its end, he and his works have continuing

relevance to the medium in our own time. Edward Steichen appears as one of those

cultural forces that each generation must discover anew and reevaluate for itself. This

round of the discussion has only begun.

© Copyright 2007 by A. D. Coleman. All rights reserved. By permission of the author and Image/World Syndication Services, [email protected].

60 An an indication of its ongoing potency, consider the show and catalogue Humanism in China: A Contemporary Record of Photography, organized by the Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, and first shown there in 2003, then in the Shanghai Art Museum in 2004. It made its debut in the west at the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, May 20–August 27, 2006. This 50-year survey includes some 600 images by more than 100 photographers; it explicitly "takes as its inspiration Edward Steichen's landmark show [The Family of Man]." See the essay by the curators, An Ge, Hu Wugong, and Wang Huangsheng, in the catalogue Humanism in China: A Contemporary Record of Photography (Heidelberg: Edition Braus im Wachter Verlag, 2006), German and English-language version of the original Chinese version published in 2003 by Lingnan Art Publishing House, Guangzhou. 61 See, for example, Patricia Vettel-Becker, "Destruction and Delight: World War II Combat Photography and the Aesthetic Inscription of Masculine Identity," Men and Masculinities, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2002), pp. 80-110.