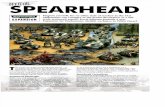

Spearhead: Armored Forces in Normandy

Transcript of Spearhead: Armored Forces in Normandy

1

Spearhead: Armored Forces in Normandy

M4 Sherman tank crew at Fort Knox, Kentucky, 1942. Courtesy of The Atlantic.

Michael Kern

Program Assistant, National History Day

2

“Rapidity is the essence of war; take advantage of the enemy’s unreadiness, make your way by unexpected routes, and attack unguarded spots.”

- Sun Tzu, The Art of War

3

What is National History Day?

National History Day is a non-profit organization which promotes history education for secondary and elementary education students. The program has grown into a national program since its humble beginnings in Cleveland, Ohio in 1974. Today over half a million students participate in National History Day each year, encouraged by thousands of dedicated teachers. Students select a historical topic related to a theme chosen each year. They conduct primary and secondary research on their chosen topic through libraries, archives, museums, historic sites, and interviews. Students analyze and interpret their sources before presenting their work in original papers, exhibits, documentaries, websites, or performances. Students enter their projects in contests held each spring at the local, state, and national level where they are evaluated by professional historians and educators. The program culminates in the Kenneth E. Behring National Contest, held on the campus of the University of Maryland at College Park each June.

In addition to discovering the wonderful world of the past, students learn valuable skills which are critical to future success, regardless of a student’s future field:

• Critical thinking and problem solving skills • Research and reading skills • Oral and written communication and presentation skills • Self-esteem and confidence • A sense of responsibility for and involvement in the democratic process

Participation in the National History Day contest leads to success in school and success after graduation. More than five million NHD students have gone on to successful careers in many fields, including business, law, and medicine. NHD helps students become more analytical thinkers and better communicators, even if they do not choose to pursue a career in history.

4

What is the Normandy Scholars Institute?

Established in 2011, the Normandy Scholars Institute is a program which teaches high school students and teachers about D-Day and the fighting in Normandy during World War II. The program is a partnership between National History Day and The George Washington University made possible by the generosity of Albert H. Small. Mr. Small is a veteran of the U.S. Navy who served in Normandy during World War II. He is passionate about history education and wants to ensure that the sacrifices of World War II veterans are honored and remembered by America’s youth.

Each winter National History Day selects a group of teachers from across the country to participate in the program. Each teacher selects a student to work with during the institute. The teacher and student work as a team, learning side-by-side, making the institute a unique educational experience. Starting in spring, the team reads books on World War II and on D-Day, giving them a better understanding of the history and historical context of the campaign. Each student selects a soldier from their community who was killed during the war and who is buried at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. The team works with a research mentor to learn about the life of their soldier. In June, the teams travel to Washington, DC for several days of program events before flying to France to visit the historical sites where the teams’ soldiers fought and died. The trip culminates with a trip to the American cemetery where the student reads a eulogy in front of their soldier’s grave. After returning to the United States, the students and teachers share their experience with others by making a website about their soldier and giving presentations at their schools.

In addition to getting to experience Normandy firsthand, students and teachers will:

• Learn the true cost of war and the meaning of freedom and sacrifice • Improve research and problem solving skills • Attain a deeper understanding of America’s participation in World War II • Establish relationships with peers and colleagues from across the country

5

Table of Contents

Introduction…………………………………………..6

Armor Combat, 1916-1941…………………………...7

The Armored Division………………………………..9

Armored Regiment and Tank Battalion……………...12

Armored Infantry Regiment or Battalion…………….17

Armored Field Artillery Battalion……………………21

Cavalry Reconnaissance Battalion or Squadron……..25

Tank Destroyer Battalion…………………………….29

Armor Combat in Normandy………………………...33

Resources…………………………………………….37

Bibliography…………………………………………43

6

Introduction

This guide covers U.S. armored forces in Normandy. It should be a useful reference to students researching a soldier who served with any of the types of units listed below. This guide discusses the history, organization, tactics, and combat experiences of the men in these units. It is worth reading all sections of this guide regardless of the type of unit your soldier served with, because these units all worked together.

• Armored Regiment or Tank Battalion • Armored Infantry Regiment or Armored Infantry Battalion • Armored Field Artillery Battalion • Cavalry Reconnaissance Battalion or Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron • Tank Destroyer Battalion

M5A1 Stuart tank creeps through a French town, 1944. Army Signal Corps Photo. 111-SC-191237-SA. Courtesy National Archives.

7

Armor Combat, 1916-1941

The tank was developed during World War I, first seeing combat during 1916. The first large-scale use of tanks occurred the following year, at the Battle of Cambrai. Germans soldiers were unable to resist the British tanks, creating a significant penetration in the German lines. Early tanks had very thin armor, could only move about three miles per hour, and tended to give their crews carbon monoxide poisoning. They were used in small numbers along the front line to support infantry attacks – a few tanks here, a few tanks there. By the end of the war, the Allies were learning to use tanks more effectively – the British Army launched a very successful attack at Amiens in August 1918 using tanks, infantry, artillery, and airplanes together, as part of a team. The German Army did not develop tanks until 1918; many German officers believed that the German Army’s lack of tanks was a major factor in its defeat. After the war, tank development moved quickly. Tanks became faster, better armored, more mechanically reliable, and more powerful in combat.1

During the 1920s and 1930s, a debate raged about the best way to use tanks. Some British Army officers argued that in the next war tanks should be used like they were used in World War I – as mobile bunkers to support infantry attacks. Other officers – most notably J. F. C. Fuller and B. H. Liddell Hart – believed that the tank made old ways of war obsolete. Fuller believed that in future wars infantry and artillery forces would create ‘harbors’ from which tank fleets could operate. The tanks would cruise out of their harbor, find the enemy’s tanks, and defeat them in battle. The British Army’s officers could not make up their minds about whose vision of war was correct, so the Army built two types of tanks – ‘infantry’ tanks that were slow but heavily armored and ‘cruiser’ tanks that were fast but poorly protected.

2

The United States Army also experimented with tank units during the 1920s and 1930s, though American experiments were always modest, because of lack of funding. Nevertheless, forward-thinking Army generals like Adna Chaffee, Jr. and Daniel van Voorhis pushed the Army to create armored units and to develop tactics. The first post-WWI American tank unit was the Experimental Mechanized Brigade, formed in 1928. Chaffee used the brigade to develop new tactics for American tank units. Unlike the British experiments, Chaffee argued for a middle-of-the-road course. He believed that tanks were powerful weapons which could help bring victory on the battlefield, but only if they had help. Chaffee wanted a ‘combined arms’ armored force – units of tanks, infantry, artillery, and airplanes all working together as a team. The infantry

1 Tanks in WWI, Paddy Griffith. Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army’s Art of Attack 1916-18. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994, 104-111; and 20s and 30s tank development, Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett. Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge Press, 1996, 6-49. 2 British tank development and Fuller, Murray and Millet, 19-29; Liddell-Hart’s views, B. H. Liddell-Hart. Strategy: The Classic Book on Military Strategy. New York: Meridian, 1991, 187-206.

8

supported the tanks and protected them from anti-tank weapons. Artillery batteries bombarded enemy positions, weakening them so that the tanks could overwhelm them. Airplanes bombed particularly tough enemy positions so that the tanks could move past them. His dream was realized in 1936, when the Army created the 7th Cavalry Brigade (Mechanized), the first American combined arms tank unit.3

While the U.S Army was slowly building its tank forces and developing new ways of using them, the Germans were adapting and extending American methods. Determined to make good use of the tank in a future war, the German Army’s General Staff studied tank warfare extensively during the 1920s and 1930s and decided that the combined arms approach was the best way to use tanks. When the German Army launched its invasion of the West in 1940, its combined arms panzer units were the spearhead of its attack. German panzer divisions slashed through French and British defenses, destroying enemy units and surrounding or bypassing those it could not destroy. Using these blitzkrieg tactics, the German Army achieved stunning results. German panzer units raced across France, sweeping away all resistance in their path. Brigadier General Isaac D. White of the 2nd Armored Division stated that “the 7th Cavalry Brigade (Mechanized) served as a model for the Germans to copy. The soundness of American tactical doctrine was proven in Poland, the Low Countries and France.” In response to German battlefield successes and to American successes in maneuvers, the U.S. Army created its first two armored divisions in 1940. By the end of the war, the Army would have sixteen armored divisions and would be the most mechanized army in the world.

4

Angiet Hutaf, Treat Em Rough! Join the Tanks, 1918 Courtesy Center of Military History Art Collection

3 American experiments, Donald E. Houston. Hell on Wheels: The 2d Armored Division. Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1977, 1-31. 4 German 1940 campaign, Ronald E. Powaski. Lightning War: Blitzkrieg in the West, 1940. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons, 2003; the 7th Cavalry Brigade,” I. D. White quoted in Houston, 31; and creation of armored divisions, Houston, 33-35.

9

The Armored Division

The U.S. Army formed sixteen armored divisions during World War II. The structure of the armored division was overhauled in 1943. The 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions kept the early organization. The other fourteen divisions used a new organization with only half as many tanks. These divisions were referred to as ‘light’ armored divisions. The 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions were ‘heavy’ divisions, composed of about 10,937 men, with 159 medium tanks and 68 light tanks. Here is the organization of a ‘heavy’ armored division (2nd or 3rd Armored Division):5

• Division Headquarters

o Headquarters Company o Signals Company o Service Company o Ordnance Maintenance Battalion o Armored Medical Battalion o Cavalry Reconnaissance Battalion o Armored Engineer Battalion o 3x Armored Field Artillery Battalions o 2x Armored Regiment

Headquarters Company Service Company Reconnaissance Company Tank Battalion (Light) 2x Tank Battalion (Medium)

o Armored Infantry Regiment Headquarters Company Service Company 3x Armored Infantry Battalions

Armored divisions usually received support from a tank destroyer battalion and from an anti-aircraft battalion. The division’s signals company operated radios and telephone equipment to communicate with the units within the division and to communicate with other divisions and with the corps headquarters. The service company ensured that the division’s units received the

5 Sixteen armored divisions, Lone Sentry: Photos, Articles & Research on the European Theater in World War II. “Campaigns of U.S. Army Divisions in Europe, North Africa, and Middle East.” Accessed October25, 2011. http://wwww.lonesentry.com/usdivisions/campaigns.html; and heavy armored division organization, Gary Kennedy. “The United States Armored Division 1942 to 1943.” Battalion Organizations During the Second World War. Accessed October 25, 2011. http://www.bayonetstrength.150m.com/UnitedStates/Divisions/Armd%20Divs/united_states_armored_division%201943%20to%201943.htm; and Andrew Mollo. The Armed Forces of World War II: Uniforms, insignia and organization. New York: Crown Publishers, 1981, 151.

10

supplies and equipment they needed to keep fighting. The ordinance maintenance battalion repaired the division’s vehicles. This is how the ‘light’ armored division was organized:6

• Division Headquarters

o Headquarters Company o Signals Company o Service Company o Ordnance Maintenance Battalion o Armored Medical Battalion o Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron o Armored Engineer Battalion o 3x Armored Field Artillery Battalions o 3x Tank Battalions o 3x Armored Infantry Battalions

Armored infantrymen in halftracks at Fort Benning, Georgia, 1942. Army Signal Corps Photo. 111-SC-136438. Courtesy National Archives.

The key difference was that the light armored division had only three tank battalions,

while the heavy division had six tank battalions. To make things even more confusing, armored divisions divided their troops up into semi-independent combined arms organizations called ‘combat commands.’ Each combat command was like a miniature army: it had tank, armored infantry, and armored field artillery battalions, in addition to engineer, reconnaissance and

6 Light armored division, Gary Kennedy. “The United States Armored Division 1944 to 1945,” Battalion Organization During the Second World War.” Accessed October 25, 2011. http://www.bayonetstrength.150m.com/UnitedStates/Divisions/Armd%20Divs/united_states_armored_division%201944%20to%201945.htm

11

medical units. The division had three combat commands, labeled A, B, and R. CCA and CCB were the main fighting units of the division. CCR was kept in reserve, ready to help CCA or CCB if either of them got into trouble. For example, here is the organization of the 2nd Armored Division’s CCB in Normandy:7

• CCB Headquarters

o 1st Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment o 2nd Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment o 1st Battalion, 41st Armored Infantry Regiment o 3rd Battalion, 41st Armored Infantry Regiment o 78th Armored Field Artillery Battalion o Company C, 702nd Tank Destroyer Battalion o Company B, 48th Armored Medical Battalion o Battery A, 195th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion o Company B, 17th Armored Engineer Battalion o 502nd CIC Detachment

The combat command was a combined arms organization with many different types of units working together. The Army’s tank battalion field manual stressed the importance of using combined arms teamwork: “The effectiveness of offensive action is dependent upon the coordinated teamwork of all components in the attacking force. This teamwork is assured when each arm understands the capabilities, limitations, and techniques of all arms. Mutually understood doctrines of employment utilize the capabilities of one to offset the limitations of the others.”8

A jeep trudges through a muddy lane in bocage country, Normandy 1944. Courtesy Stolly.org.uk.

7 Combat commands, Kennedy, “Armored Division 1944 to 1945;” and CCB order of battle, U.S. 2nd Armored “Hell on Wheels” Division. “’Hell on Wheels’ Constitution circa July ‘44.” Accessed October 26, 2011. http://www.2ndarmoredhellonwheels.com/units/july44.html. 8 “The effectiveness of combined,” War Department. Tank Battalion, FM 17-33. December 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944, 95.

12

Armored Regiment and Tank Battalion

The tank portion of an armored division was made up of tank battalions. In a heavy armored division, tank battalions were grouped into armored regiments. In light armored divisions, tank battalions were not grouped. About half of the Army’s tanks were sent to armored regiments and tank battalions belonging to an armored division. The other half were sent to ‘GHQ’ tank battalions – independent tank battalions attached to infantry divisions (they were called ‘GHQ’ battalions because they were under the command of the Army’s General Headquarters). Whether your soldier belonged to an armored regiment or a tank battalion, this section will help you understand your soldier’s unit. If he did belong to a tank battalion instead of an armored regiment, just ignore the section on the armored regiment’s organization.9

Since tanks were armed with a long range cannon and machineguns that could hit a target 800 or more yards away, tanks were best suited to working in open terrain like rolling hills and fields. Even under these conditions, tanks needed to work closely with infantry to be most effective. The tanks and infantry formed a team – the tanks helped eliminate German machineguns and infantry squads which slowed the American infantry advance and the infantry protected the tanks from German anti-tank teams and helped the tanks spot targets (tank crews have only a small field of view from inside the tank). Sometimes the tanks supported an infantry attack and sometimes the infantry supported a tank attack. It all depended on the particular situation. In the claustrophobic bocage country of Normandy, close cooperation with infantry was absolutely vital to the survival of the tank crewmen. The tank battalion field manual noted that

“The cooperation of all elements must be insured. Each commander must understand that his unit is only part of a team and that he must work in close cooperation with all other units. Teamwork is obtained by combined training. Tanks can take terrain but they cannot hold it. Tanks must not be expected to neutralize an objective for a long period of time.”10

9 Organization, Kennedy, “Armored Division 1942 to 1943” and “Armored Division 1944 to 1945;” GHQ battalions, Mollo, 232-233. 10 Armament, War Department, Tank Battalion, 11, 13; favorable terrain, War Department, Tank Battalion, 3; tank-infantry cooperation, War Department. “Tank-Infantry Teamwork,” Combat Lessons No. 9, 1945. Accessed October 11, 2011. http://www.lonesentry.com/combatlessons/index.html; and “the cooperation of all,” 2; and “the cooperation of all,” War Department, Tank Battalion, 2.

13

An armored regiment had three tank battalions, supported by a headquarters company, a service company, and a cavalry reconnaissance company. The regiment was commanded by a colonel, with a lieutenant colonel as his executive officer (second-in-command). The headquarters company provided the men to handle the command, administration, and communications duties for the regiment. The headquarters company also included the various staff officer sections and provided bodyguards for the regiment’s commander. The service company maintained the regiment’s vehicles, brought supplies to the regiment’s troops, and evacuated wounded soldiers to the division’s medical battalion. The cavalry reconnaissance company scouted for the regiment. The reconnaissance company’s organization is discussed in the ‘Cavalry Reconnaissance Battalion’ section of this document. Here is the organization of the armored regiment:11

• Headquarters Company • Service Company • Cavalry Reconnaissance Company • 3x Tank Battalions

Each tank battalion had four companies of tanks, supported by headquarters, medical, and maintenance units:

• Tank Battalion

o Headquarters Company o Service Company o Medical Detachment o 3x Medium Tank Companies o Light Tank Company

The Headquarters Company had a reconnaissance platoon, a mortar platoon, and an assault gun platoon (5 Sherman tanks armed with 105mm guns which specialized in knocking out buildings and bunkers) in addition to their normal administrative and command staffs. The main fighting power of the battalion was the three medium tank companies:12

• Medium Tank Company (5 officers, 116 men) o Company Headquarters (1 officer, 16 men with 3 tanks and 1 vehicle) o Maintenance Section (1 officer, 9 men with 3 vehicles) o Admin, Supply & Mess Section (19 men with 1 vehicle) o 3x Tank Platoons (each 1 officer, 24 men with 5 tanks)

11 Armored regiment organization, Kennedy, “Armored Division 1942 to 1943.” 12 Tank Battalion organization, War Department. Tank Battalion, 5.

14

The medium companies did most of the fighting if the battalion needed to assault a German-held town or other defensive position. Medium tank companies were equipped with either M4A1 Sherman tanks or M4A3 Sherman tanks, which were practically identical. They were armed with a 75mm cannon, two .30 caliber machineguns and a .50 heavy machinegun for air defense. In July, medium tank companies began receiving M4A1 tanks with a long-barreled 76mm gun which was more effective against German tanks. One tank in the company headquarters was armed with a 105mm gun, which was better for use against buildings, hedgerows, etc. The light tank company’s M5A1 Stuart tanks were faster than the Sherman, but had less firepower. Both tanks had 2” of armor to protect them. Stuart tanks had a 37mm gun, two .30 caliber machineguns and a .30 machinegun for air defense. They were used for scouting missions rather than for assaults whenever possible:13

• Light Tank Company (5 officers, 91 men) o Company Headquarters (1 officer, 9 men with 2 tanks and 1 vehicle) o Maintenance Section (1 officer, 9 men with 3 vehicles) o Admin, Supply & Mess Section (16 men with 1 vehicle) o 3x Tank Platoons (each 1 officer, 19 men with 5 tanks)

Sherman tanks had a crew of five men. A private or private first class served as the tank’s driver. Another man worked as the tank’s radio operator. He also fired the bow machinegun, located on the front right of the tank. An enlisted man served as the loader for the tank’s cannon. When the tank commander called for a particular type of shell (armor piercing, high explosive, smoke, etc.), the loader pulled the shell out of the storage bin and loaded it into the breech of the cannon. The tank’s gunner was a corporal and was second-in-command of the tank. In addition to firing the tank’s cannon, he also fired the tank’s coaxial machinegun, located right next to the cannon. The tank commander was a sergeant. He directed the movement and fire of the tank, and selected the type of shells that the gunner fired. Tank platoons were commanded by a 2nd lieutenant, who acted as tank commander for his tank in addition to acting as the platoon’s commander. The platoon sergeant of a tank platoon was a staff sergeant. The tank company was commanded by a captain. The company’s XO did not ride in a tank in battle – if the captain was killed or wounded, the most senior 2nd lieutenant took over command of the company until the 1st lieutenant could take over command. The Stuart tanks of the light company only had four man crews – the tank commander also served as the vehicle’s loader in addition to his other duties, making him a very busy man!14

13 Medium tank company organization, War Department, Tank Battalion, 6; and tank characteristics and employment, War Department. Tank Battalion, 9-13. 14 Light tank company, War Department, Tank Battalion, 7; and tank crew jobs, War Department, Tank Battalion, 6-7.

15

In combat, tanks used ‘fire and maneuver’ tactics similar to those used by the infantry. Tanks were vulnerable to anti-tank weapons like cannons and handheld rocket launchers. When a tank platoon was attacking, part of the platoon used their cannons and machineguns to fire on the German troops so that the other tanks could move forward. By shooting at the German troops or tanks, the American tanks ‘suppressed’ them – they forced the Germans to stop shooting and find protection or else risk getting shot. Armored infantry worked with the tanks to suppress anti-tank weapons so that the tanks could move forward. The tank battalion manual stated that “the battalion advances by fire and maneuver, the maneuvering element always being covered by a supporting element. When the maneuvering force has advanced to the limit of supporting distance, it may, in turn, support the movement of the remainder of the command.”15

M5A1 Stuart tank with Culin hedgerow cutter added. Army Signal Corps Photo 111-SC-193417-S. Courtesy National Archives.

Armored regiments carried unique numbers. ‘Independent’ tank battalions also carried unique numbers, but battalions belonging to an armored regiment were numbered. E.g. the 67th Armored Regiment had 1st, 2nd, and 3rd battalions, while the 8th Tank Battalion was part of the 4th Armored Division. Companies were lettered A, B, C, and D, while platoons were numbered 1st, 2nd, and 3rd.16

15 “The battalion advances,” War Department, Tank Battalion, 2. 16 Nomenclature, U.S. 2nd Armored “Hell on Wheels” Division. “’Hell on Wheels’ Constitution circa July ‘44.”

16

What was my soldier’s job?

This is a list of the different ranks of soldiers in the regiment or battalion, along with their most likely job. Further research should help determine exactly what role your soldier played in his unit.17

Colonel: Commanded the regiment

Lt. Colonel: Commanded a battalion or executive officer of the regiment Major: Was a staff officer or executive officer of a battalion Captain: Commanded a company or was a staff officer 1st Lieutenant: Executive officer of a company or was a staff officer 2nd Lieutenant: Commanded a platoon or maintenance section Master Sergeant: Senior NCO in the regiment or battalion and a role model for the men 1st Sergeant: Senior NCO in a company and served as a role model for the men Tech Sergeant: More senior platoon sergeant (second-in-command of a platoon) Staff Sergeant: Platoon sergeant (second-in-command of a platoon) Sergeant: Tank commander or maintenance team leader Corporal: Gunner, vehicle driver, or assistant maintenance team leader PFC/Private: Tank crewman or maintenance soldier

Not taking any chances, a M4A3 Sherman crew has their tank blessed by a chaplain. Army Signal Corps Photo. 111-SC-400326. Courtesy National Archives.

17 Jobs, War Department, Tank Battalion, 6-7.

17

Armored Infantry Regiment or Armored Infantry Battalion

Armored infantry troops were soldiers who helped the division’s tank battalions achieve their objectives. The armored infantry field manual described thirteen different missions that armored infantry soldiers could be called upon to perform to support the tanks. These missions included supporting tank attacks, capturing objectives difficult for the tanks to attack, defending territory captured by armor, and scouting missions. The tanks were the division’s main fighting strength and its most powerful weapon. But without armored infantry soldiers to support and protect them, the tanks would not be able to achieve any of their missions.18

Similarly to the tank forces, armored infantry were organized in different ways depending on if the division was a heavy or a light armored division. Light armored divisions had three armored infantry battalions. Heavy armored divisions had an armored infantry regiment, with three armored infantry battalions. If your soldier served in an armored infantry battalion, ignore the section about the armored infantry regiment.19

An Armored Infantry Regiment (AIR) consisted of three armored infantry battalions, a headquarters company, and a service company. The headquarters and service companies provided the same duties as their counterparts in the armored regiment – providing for command, communications, supply, evacuation, and maintenance activities. Here is the organization of an armored infantry regiment:20

• Headquarters Company • Service Company • 3x Armored Infantry Battalions

The Armored Infantry Battalion (AIB) had a headquarters company, a service company, and three rifle companies – a total of 39 officers and 962 men. The battalion was commanded by a lieutenant colonel and assisted by a major. The headquarters company had command and communications sections, and several specialized combat platoons. The reconnaissance platoon (1 officer, 20 men) scouted for the battalion. The assault gun platoon (1 officer, 23 men) had three M8 Scott artillery vehicles. The M8 had a 75mm howitzer mounted on a M5 light tank hull. The assault gun platoon was the battalion’s artillery and tank unit – it could fire artillery bombardments using map coordinates provided by armored infantrymen, or it could drive up to the target and blast it from close range. The mortar platoon (1 officer, 24 men) had three 81mm

18 Missions, War Department. Armored Infantry Battalion, FM 17-42. November 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944, 2-3. 19 Organization, Kennedy, “Armored Division 1942 to 1943” and “Armored Division 1944 to 1945.” 20 AIR organization, Kennedy, “Armored Division 1944 to 1945.”

18

mortars, each mounted in a halftrack. The platoon bombarded German troops to help the infantry attack. Lastly, the machinegun platoon (1 officer, 34 men) had four M1917A1 heavy machineguns. These guns provided suppression fire to help armored infantry or tanks attack German troops without getting shot.21

The battalion’s service company provided the same duties as the regimental service company: supplying the troops, fixing broken vehicles, and bringing wounded men to a casualty collection point. The battalion’s main combat component was its three rifle companies:22

• 3x Rifle Companies (6 officers, 245 men) o Company Headquarters (1 officer, 8 men) o Maintenance Section (1 officer, 6 men) o Administrative, Mess & Supply Section (34 men) o Anti-tank Platoon (1 officer, 32 men with 3x 57mm anti-tank guns) o 3x Rifle Platoons (1 officer, 48 men)

Platoon Headquarters (1 officer, 11 men) Mortar Squad (8 men with 1x 60mm mortar) Machinegun Squad (12 men with 2x light machineguns) 2x Rifle Squads (12 men)

The rifle company had three rifle platoons, administrative and maintenance sections, and an anti-tank platoon with three 57mm anti-tank guns. The company was commanded by a captain and assisted by a 1st lieutenant. The anti-tank guns were not very effective against German tanks – shells often just ricocheted off a German tank’s armor. Some company commanders were so frustrated by the 57mm gun’s lack of performance that they reorganized the anti-tank platoon and used it as another rifle platoon. The company also had a number of bazooka anti-tank rocket launchers for defense against tanks.23

The entire company was transported by M3A1 halftracks – over twenty of them. The M3A1 was an open-topped vehicle which looked like a truck. It was driven by wheels at the front of the vehicle, and tracks at the back. It could carry thirteen men and was armed with either a .50 or .30 caliber machinegun. The vehicle had armor that was thick enough to stop a bullet – usually. A cannon shell or rocket would easily destroy the vehicle. Soldiers were transported in the halftracks, but they did not fight in them. Instead, they fought on foot (it was too dangerous 21 Battalion organization, Gary Kennedy. “The United States Armored Infantry Battalion 1944 to 1945,” Battalion Organization During the Second World War. Accessed October 26, 2011. http://www.bayonetstrength.150m.com/UnitedStates/Armored/united_states_armored_infantry_battalion%201944%20to%201945.htm 22 Company organization, Kennedy. “Armored Infantry Battalion.” 23 Company organization, Kennedy. “Armored Infantry Battalion.”

19

to stay in the halftrack during a battle). Soldiers nicknamed the M3A1 the ‘Purple Heart box,’ which gives you an indication of how much protection it gave the soldiers! During an attack, the M3A1’s would drop their soldiers off behind American lines and the soldiers would attack on foot. The M3A1 drivers would try to find a place where they could hide their halftrack behind a hedge or some other protection and use the vehicle’s machinegun to provide suppression fire. In defense, the vehicles were kept behind the front line. The machineguns were taken off of the halftracks and used by the infantry for extra firepower.24

The three rifle platoons each had a mortar team, a pair of M1919 light machineguns, and two rifle squads. The machineguns provided suppression fire for the platoon during attacks, and extra firepower when defending. The guns were often split up and attached to different platoons. The mortar bombarded German troops or laid down smoke screens to help a rifle platoon attack. The platoon headquarters squad was used as a third rifle squad – it was the same size as a normal rifle squad anyway. The platoon was led by a 2nd lieutenant and assisted by a staff sergeant. The rifle squads were each twelve men strong. The squad was led by a sergeant, who was assisted by a corporal. One man served as a driver for the squad’s M3A1 halftrack and carried a M1 Thompson sub-machinegun (the famous ‘Tommy gun’ of gangster movie fame). The other men were riflemen and, in theory, all carried M1 Garand rifles. In reality, armored infantrymen tended to ‘acquire’ extra Browning Automatic Rifles (BARs) for extra firepower. The squad was divided into three teams. Able team had two scouts, which moved ahead of the squad during an attack. The scouts stayed as far ahead of the squad as they could while still staying within eyesight of the squad. Once Able team spotted German soldiers, the rest of the squad deployed for battle. The squad leader directed his other two teams to locations from which he wanted them to fight. Baker team had four men, one of which was the assistant squad leader. Baker team often had a BAR for extra firepower. Their job was to suppress the Germans who were firing on the squad. Once Baker team suppressed the enemy soldiers, Charlie team moved in for the kill. Charlie team had the other six soldiers in the squad, including the squad leader. While Baker squad kept the Germans’ heads down, Charlie team moved closer to the Germans. Once they got to within twenty or thirty yards, Charlie team used grenades and close range shooting to eliminate the enemy soldiers.25

Armored infantrymen usually fought alongside tanks when they were attacking. In the attack, armored infantry provided a number of services for the tanks:

1) Protect tanks from enemy personnel executing antitank measures.

24 Description of M3A1, Philip Trewhitt. Armored Fighting Vehicles: 300 of the world’s greatest military vehicles. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1999, 195; and use of M3A1’s for support fire, War Department, Armored Infantry Battalion, 73. 25 Weapons, Kennedy, “Armored Infantry Battalion;” and tactics, War Department, Armored Infantry Battalion, 77-79.

20

2) Seize ground from which tanks may attack. 3) Follow the tank attack closely, assisting by fire and seizing the objective, mopping up

enemy resistance, and protecting the tank reorganization. 4) Form a base of fire for the tank attack. 5) Remove or destroy obstacles holding up tank attacks.26

Armored infantry regiments carried unique numbers. ‘Independent’ armored infantry battalions also carried unique numbers, but battalions belonging to an armored regiment were numbered. E.g. the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment had 1st, 2nd, and 3rd battalions, while the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion was part of the 4th Armored Division. Companies were lettered A, B, and C, while platoons were numbered 1st, 2nd, and 3rd.27

What was my soldier’s job?

This is a list of the different ranks of soldiers in the regiment, along with their most likely job. Doing further research should help determine exactly what job your soldier had in his unit.28

Colonel: Commanded the regiment

Lt. Colonel: Commanded a battalion or was executive officer of the regiment Major: Was a staff officer or executive officer of a battalion Captain: Commanded a company or was a staff officer 1st Lieutenant: Executive officer of a company or staff officer 2nd Lieutenant: Commanded a platoon Master Sergeant: Senior NCO in the regiment and a role model for the men 1st Sergeant: Senior NCO in a company and served as a role model for the men Tech Sergeant: More senior executive officer of a platoon, aka the ‘platoon sergeant’ Staff Sergeant: Executive officer of a platoon, aka the ‘platoon sergeant’ Sergeant: Squad leader Corporal: Assistant squad leader or weapon gunner, driver PFC/Private: Rifleman, radio operator, driver, or messenger 26 Tank support missions, War Department, Armored Infantry Battalion, 62. 27 Nomenclature, U.S. 2nd Armored “Hell on Wheels” Division. “’Hell on Wheels’ Constitution circa July ‘44.” 28 War Department, Armored Infantry Battalion.

21

Armored Field Artillery Battalion The armored field artillery battalion provided artillery support for the division’s tanks and armored infantry. This was a vital task and artillery support often meant the difference between victory and defeat on the World War II battlefield. Fortunately, the U.S. Army was second to none when it came to making effective use of artillery. American artillery tactics were very sophisticated and were unsurpassed by any army in the world.29

The job of the armored field artillery battalion was to support the activities of the tank and armored infantry battalions. They did this in several ways. The battalion provided artillery barrages in support of attacks. During a battle, the battalion responded to requests for barrages from tank and infantry commanders. The battalion performed ‘counter battery’ fire to knock out German artillery batteries firing at American troops. They also attacked German reinforcements and command posts to make it more difficult for German officers to coordinate their activities and get troops to the right place on the battlefield.

30

Each armored division had three armored field artillery battalions, equipped with eighteen M7 Priest vehicles. Each M7 Priest had a 105mm howitzer which could fire a thirty-three pound shell up to seven miles. The vehicle was nicknamed ‘Priest’ because soldiers thought that the area where the machinegun was mounted looked like a church pulpit. The vehicle was crewed by seven men: a vehicle commander, a driver, and five gun crew. The battalions could be used in either direct support of a particular unit or in general support for the entire division. Usually, each combat command received support from one armored field artillery battalion. The battalion numbered 520 men:

31

• Headquarters and Headquarters Battery (14 officers, 92 men)

• Service Battery (5 officers, 89 men) • Medical Detachment (1 officer, 9 men) • 3x Batteries (each 4 officers, 101 men with 6x M7 Priests)

The service battery was responsible for the maintenance of the guns and the battalion’s vehicles. The headquarters battery provided the staff elements needed to plan fire missions, keep track of supplies, and oversee the operations of the gun batteries. The headquarters battery also had two Piper L-4 Grasshopper airplanes, used to adjust artillery bombardments. The L-4 was a tiny airplane with no weapons, but was the airplane most feared by German soldiers because it

29 American artillery tactics, Michael D. Doubler. Closing with the Enemy: How GIs Fought the War in Europe, 1944-1945. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1994, 10-30. 30 Missions, War Department. Field Artillery Tactical Employment. FM 6-20, 5 February 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944, 8-10. 31 Battalion organization, War Department. Armored Field Artillery Battalion, T/O&E No. 6-165. 22 November, 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944.

22

could call on the wraith of an entire field artillery battalion. The battalion was commanded by a lieutenant colonel with a major as his assistant. Each battery was commanded by a captain, with a 1st lieutenant as an assistant commander.32

During combat operations, a battery could be in ‘direct’ or ‘general’ support of a military unit. Batteries in direct support of a unit in effect were attached to that unit. The battery was assigned to support that particular unit with whatever artillery support they needed. Batteries in general support were not attached to a particular unit. Instead they provided support on an as needed basis for any unit that needed artillery fire. Artillery was not kept in reserve – since artillery fire could be quickly switched from target to target the division’s artillery batteries were kept firing as much as possible, as circumstances and ammunition supply allowed.

33

Batteries providing direct support for an infantry unit provided a team of forward observers (FOs) that went up to the front line with the infantry or tank unit. The forward observer team consisted of several men, lead by an officer or NCO from the battery in direct support. The forward observers had a radio with which they could contact their battery to request fire missions. All men in the FO team were trained to adjust and coordinate artillery missions. In addition to ground-based FO teams, the battalion had two airplanes which they used for Forward Observation missions. Infantrymen and tank crews were also trained in forward artillery observation, in case an FO team was not available or had been incapacitated. Soldiers down to the rank of staff sergeant knew how to call for artillery missions.

34

Because guns had a range of several miles, it was very rare for the gunners to be able to see their target. Almost without exception, artillery missions were ‘indirect;’ that is, the gunners received instructions by radio from an FO who could see the target. The FO radioed a description of the target (“enemy infantry,” or “enemy tanks,” etc.) and map coordinates of the target’s location to the battery’s Fire Direction Center (FDC). Each battery had a fire direction center, and the battalion and division also had FDCs. The FDC decided what priority the request should receive, in relation to the other requests being sent by other units. The FDC then performed mathematical calculations based on the target’s range, elevation, and other factors. The FDC staff then took the number received from that calculation and looked up the relevant aiming instructions for that data in a binder full of artillery aiming data. The FDC could then send the aiming instructions to the gunners who would perform the fire mission. If a battery FDC felt that a mission was particularly important, they could coordinate with the battalion FDC or the division FDC to get the entire battalion or even multiple battalions to fire at the target. The U.S.

32 Headquarters and Service Batteries, Joseph Balkoski. Beyond the Beachhead: The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999, 104 and 287; and L-4’s and ranks, War Department, Armored Field Artillery Battalion. 33 Support options, War Department, Field Artillery, 8-10. 34 Forward observers, Balkoski 110-111 and Doubler 19-20; and air observers, Balkoski, 111-112.

23

Army was the only army in the world to use this system, which allowed artillerymen to provide maximum support on a moment’s notice to any unit in need of assistance.35

The Fire Direction Center concept also allowed Americans to use an advanced technique called a ‘time-on-target’ barrage. Most casualties from artillery fire occurred in the first few seconds of an attack, when troops might be caught outside of trenches or buildings by the unexpected barrage. American artillery batteries learned how to calculate the firing of their guns so that multiple batteries could hit an area at the same time, providing maximum damage to the target.

36

Before a planned infantry or tank attack, the FO team worked with their battery’s FDC to ‘register’ targets for the planned bombardment. Registering targets required preparing information on the range and elevation of the targets to be bombarded so that the FDC could calculate aiming instructions for the bombardment. At the pre-planned time, the battery or battalion bombarded the target with shells, supporting the attack by ‘suppressing’ the German defenders (i.e. making them keep their heads down and not shoot). Once the American infantry or tanks moved within 100-200 yards of the barrage, the FO team ordered the battery to stop firing so that Americans were not hit by accident.

37

The FO team could also request impromptu artillery missions against targets which had not been registered. This occurred frequently, either when the Germans attacked an American unit or when an American attack stalled and needed extra help. Artillery fire needed to be ‘adjusted’ to perform an impromptu fire mission, because there was not enough time to gather the precise ranging and elevation measurements needed for the FDC to calculate aiming. The Forward Observer sent map coordinates to the battery as usual. Then one vehicle from the battery fired a ‘ranging’ shot. The Forward Observer noted where the ranging shot landed and gave the battery instructions on how to move the fire so that it hit the target (“up 200, left 50 yards,” etc.). The battery continued to fire ranging shots until the shells landed where the FO wanted them to land. Once the ranging shot was on target, the FO called for ‘fire for effect’ and the entire battery or battalion bombarded the target until the FO ordered them to cease firing.

38

The battalion carried a unique number. The batteries in the battalion were lettered: A, B, and C.

39

35 Fire Direction Centers, Balkoski, 112-115. 36 Time-on-target, Doubler, 19, 67. 37 Bombardments, Doubler, 19. 38 Impromptu fire missions, Balkoski, 114-115. 39 Nomenclature, War Department, Armored Field Artillery Battalion.

24

What was my soldier’s job?

This is a list of the different ranks of soldiers in the battalion, along with their most likely job. Further research should help determine exactly what role your soldier played in his unit.40

Lt. Colonel: Commanded the battalion

Major: Was a staff officer or executive officer of the battalion Captain: Commanded a battery or was a staff officer 1st Lieutenant: Executive officer of a battery or was a staff officer 2nd Lieutenant: Commanded a section Master Sergeant: Senior NCO in the battalion and a role model for the men 1st Sergeant: Senior NCO in a battery and served as a role model for the men Tech Sergeant: More senior executive officer of a section Staff Sergeant: Executive officer of a section Sergeant: Commanded a gun squad or a maintenance squad Corporal: Gunner, vehicle driver, or assistant maintenance team leader PFC/Private: Carried and loaded ammunition for a gun, or was a driver or radio operator

Poster of M7 Priest howitzer motor carriage firing. Tank Destroyer in Action, Mead Schaeffer. Courtesy Center of Military History.

40 Jobs, War Department, Armored Field Artillery Battalion.

25

Cavalry Reconnaissance Battalion or Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron

Cavalry reconnaissance troops performed scouting duties for the division using fast jeeps, trucks, and armored cars. Cavalry troops usually tried not to fight – that was not their job. Still, there were many times when the cavalry troopers needed to fight their way through German defenses to reach their objective. The cavalry troop field manual stated that “reconnaissance missions are performed by infiltration tactics, fire, and maneuver. Combat is engaged in only to the extent necessary to accomplish the assigned mission.” In addition to scouting, they also showed their value after the Army broke through German defenses in August 1944. Cavalry troopers sped ahead of the advancing troops and tanks, capturing bridges before the Germans could destroy them and ambushing German convoys of trucks and tanks behind German lines. As with the tanks and the infantry, heavy armored divisions and light armored divisions used different cavalry organizations. Heavy armored divisions had a cavalry reconnaissance battalion and light armored divisions and infantry divisions had a cavalry reconnaissance squadron.41

The cavalry troopers used several different types of vehicles. The most common was the M8 Greyhound armored car. An armored car was a vehicle designed for scouting. Think of it like a tank with wheels instead of tracks. The M8’s armor was light, but was thick enough to protect the crew from bullets and shell fragments. The M8 was the fastest armored vehicle in the world in 1944 – well earning its nickname of ‘Greyhound.’ The car had a crew of four men – a driver, a radio operator, a gunner, and a vehicle commander. The commander also served as the gun’s loader. The vehicle was armed with a 37mm cannon and .30 caliber and .50 caliber machineguns. Other men in the unit rode in jeeps, fast vehicles which could carry three men and a mortar or machinegun. Cavalry troops could call on support from M5A1 Stuart light tanks and M8 Scott artillery vehicles.42

The 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions had cavalry reconnaissance battalions instead of squadrons. The battalion had a headquarters company, a light tank company, and three cavalry reconnaissance companies. The battalion numbered 872 men and had 49 armored cars and 17 light tanks:43

41 Cavalry Missions, War Department. Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron Mechanized, FM 2-30. 28 August, 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944, 20-21; “reconnaissance missions,” War Department, Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop Mechanized, FM 2-20. 24 February, 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1994, 2; cavalry operations during the breakout, Martin Blumenson. Breakout and Pursuit. Washington: Center of Military History, 1993; cavalry reconnaissance battalion, Kennedy, “Armored Division 1942 to 1943;” and cavalry reconnaissance squadron, Kennedy, “Armored Division 1944 to 1945.”

42 Description of M8 armored car, Trewhitt, 156. 43 Cavalry reconnaissance battalion organization, Gary Kennedy. “The United States Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, 1942 to 1943.” Battalion Organization during the Second World War. Accessed October 27, 2011. http://www.bayonetstrength.150m.com/Reconnaissance/Recon/united_states_armored_reconnaissance%20battalion.htm.

26

• Cavalry Reconnaissance Battalion o Headquarters Company o Light Tank Company o 3x Cavalry Reconnaissance Company

The headquarters company provided command, communications, supply, maintenance, and medical evacuation duties for the battalion. The light tank company was organized in the same way as a normal light tank company – see the Armored Regiment section for details. The main fighting part of the battalion was the three cavalry reconnaissance companies:44

• Cavalry Reconnaissance Company (9 officers, 193 men) o Headquarters Section (2 officers, 29 men with 2x M8 armored cars) o Administrative, Mess & Supply Section (20 men) o Maintenance Section (1 officer, 18 men with 1x M8 armored car) o 3x Cavalry Reconnaissance Platoons (each 2 officers, 42 men)

Armored Car Section (1 officer, 23 men with 4x M8 armored cars) Scout Section (1 officer, 11 men with 4x jeeps and 2x 60mm mortars) Assault Gun Section (8 men with 2x M8 Scott howitzer motor carriers)

M8 armored car in Paris, September 1944. Photo 208-YE-68. Courtesy National Archives.

44 Roles and company organization, Kennedy, “Armored Reconnaissance Battalion.”

27

The scout section of the cavalry reconnaissance platoon did most of the scouting. Generally, scouting was done on foot. The jeeps were used to quickly get to the area near the objective. The section was commanded by a 2nd lieutenant, with a sergeant and two corporals as assistants. They were backed up by the armored car section, which had more firepower than the scouts. The assault gun section provided close range artillery support for the scouts or armored cars when they needed help dealing with German forces. The M8 Scott’s could fire artillery bombardments or attack targets directly at close range.45

Light armored divisions had cavalry reconnaissance squadrons instead. They performed the same mission and had the same vehicles as the cavalry battalion; they were just organized a little differently. The squadron had a headquarters troop, a cavalry assault gun troop, a light tank company, and four cavalry reconnaissance troops:46

• Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron o Headquarters Troop o Cavalry Assault Gun Troop o Light Tank Company o 4x Cavalry Reconnaissance Troops

The headquarters troop performed the same duties the headquarters company performed in the cavalry battalion. The light tank company was also identical to its counterpart in the cavalry reconnaissance battalion or in the tank battalion. The cavalry assault gun troop had four platoons, each with two M8 Scott artillery vehicles. These were often split up, with each platoon supporting a cavalry reconnaissance troop.47

• Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop o Headquarters Section (2 officers, 13 men with 2x M8 armored cars) o Administrative, Mess & Supply Section (31 men) o Maintenance Section (12 men with 1x M8 armored car) o 3x Cavalry Reconnaissance Platoons (each

Armored Car Section (1 officer, 11 men with 3x M8 armored cars) Scout Section (17 men with 6x jeeps, 3x 60mm mortars and 3x light

machineguns) 45 Roles, War Department, Cavalry Troop, 86-94. 46 Cavalry reconnaissance squadron organization, Gary Kennedy. “The United States Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, Mechanized.” Battalion Organization during the Second World War. Accessed October 27, 2011. http://www.bayonetstrength.150m.com/Reconnaissance/Recon/united_states_cavalry_reconnaissance%20squadron.htm. 47 Squadron and troop organization, Kennedy, “Cavalry Squadron.”

28

The cavalry reconnaissance platoons were organized in a similar way to those in the cavalry battalion. The major change being the lack of M8 Scott’s, which were moved to the cavalry assault gun company. The squadron numbered 931 men, with 52 armored cars and 17 light tanks. Reconnaissance squadrons belonging to infantry divisions were a little smaller, having only three reconnaissance troops and three assault gun platoons, for a total of 760 men.48

Battalions and squadrons carried unique numbers. Companies and troops were lettered: A, B, C, and D. Platoons were numbered: 1st, 2nd, 3rd. Sections were referred to by their job. E. g. scout section, 1st platoon.49

What was my soldier’s job?

This is a list of the different ranks of soldiers in the battalion, along with their most likely job. Further research should help determine exactly what role your soldier played in his unit.50

Lt. Colonel: Commanded the battalion/squadron

Major: Was a staff officer or executive officer of the battalion/squadron Captain: Commanded a company/troop or was a staff officer 1st Lieutenant: Executive officer of a company/troop, was a staff officer, or platoon leader 2nd Lieutenant: Commanded a platoon or a scout section Master Sergeant: Senior NCO in the battalion/squadron and a role model for the men 1st Sergeant: Senior NCO in a company/troop and served as a role model for the men Tech Sergeant: More senior executive officer of a platoon Staff Sergeant: Executive officer of a platoon Sergeant: Vehicle commander or assistant scout section leader Corporal: Vehicle commander PFC/Private: Scout or vehicle crewman

48 Platoon organization and manpower stats, Kennedy, “Cavalry Squadron.” 49 Nomenclature, U.S. 2nd Armored “Hell on Wheels” Division. “’Hell on Wheels’ Constitution circa July ’44” and Kennedy, “Cavalry Squadron.” 50 Jobs, Kennedy, “Armored Reconnaissance Battalion” and “Cavalry Reconnaissance Battalion.”

29

Tank Destroyer Battalion

The tank destroyer force was a child of World War II. They were created in 1941 and they were disbanded in 1946. Tank destroyer battalions were independent units tasked with the destruction of German tanks. Armored divisions and infantry divisions could expect to have one battalion of tank destroyers attached. The battalions were independent of the division, being controlled by the Army Ground Forces’ General Headquarters. Tank destroyer battalions were either self-propelled or towed. Self-propelled battalions had vehicles which looked a lot like tanks. Self-propelled battalions were often attached to armored divisions, where their speed allowed them to keep up with the tanks. Towed battalions used anti-tank cannons towed by trucks. These units were not as mobile as their self-propelled counterparts and were usually used to support infantry divisions.51

Even though tank destroyer (TD) units were supposed to specialize in destroying tanks, they were not well-equipped for the job. Chief of the Army Ground Forces Lt. General Lesley McNair decreed that tanks should be designed to fight infantry and tank destroyers should fight tanks. American anti-tank weapons were underpowered, compared to their German equivalents. Tank destroyer units struggled to fight better armed and better armored German tanks. The tank destroyers were not even armed with weapons designed to fight tanks – the 3” and 90mm guns used by American TD’s were anti-aircraft guns modified for use against tanks! The tank destroyer soldiers used stealth and cunning to accomplish their mission. Nevertheless, enthusiasm for tank destroyers declined among non-TD soldiers during the last two years of the war, leading to tank destroyer units being used in other roles, as tanks or artillery pieces. Tank Destroyers did it all – they supported infantry attacks with firepower, performed artillery bombardments for infantry and tanks, and destroyed German bunkers. Considering the limitations of their weapons, tank destroyer units did an outstanding job during the war. A tank destroyer field manual noted that

“Tanks and armored cars can be destroyed only by tough and determined fighting men who are masters of their weapons. Tank destroyer soldiers are taught that they must be superior soldiers. The moral qualities of aggressiveness, group spirit, and pride in an arduous and dangerous combat mission must pervade each tank destroyer unit. All ranks must possess a high sense of duty, an outstanding degree of discipline, a feeling of mutual loyalty and confidence with regard to their comrades and leaders, and a conscious pride in their organization.”52

51 Tank destroyer history and organization, Harry Yeide. The Tank Killers: A History of America’s World War II Tank Destroyer Force. Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2004.

52 American tank design and inferiority, Belton Y. Cooper. Death Traps: The Survival of an American Armored Division in World War II. New York: Ballantine Books, 1998, 335-339; TD roles, War Department, Tactical

30

Tank destroyer battalions were usually held in reserve behind the lines, ready to counter a German tank attack. The battalion’s reconnaissance troops scouted for German tanks. Once they were found, the battalion concentrated as many tank destroyers in the area as possible. TD crews moved into ambush positions and concealed their vehicles or guns. They also prepared secondary positions where they could retreat to and keep fighting. TD battalions were not split up and attached to many units, if possible, as GHQ tank battalions often were; it was important to be able to bring maximum strength to bear to defeat the German attack.53

Self-propelled tank destroyer battalions were equipped with one of several types of vehicles. The most common tank destroyer was the M10 Wolverine. The M10 was fast and was armed with a 3” cannon, but had only 1.5” of armor (compared to 2” for M4 and M5 tanks). Less common were M18 Hellcat tank destroyers. The M18 also had a 3” gun. It had only 1” of armor, but was one of the fastest armored vehicles of the war. The M18 was small, easily hidden, and maneuverable. Despite its fragile appearance, the Hellcat had the distinction of having the lowest loss rate of any American armored vehicle of the war. The last TD was the M36 Jackson, which began arriving in Europe in September 1944. The M36 was armed with a more powerful 90mm gun, making it the best tank-killer in the American arsenal. The vehicle had over 3” of armor, but was slower than the M10 or M18. All three TD designs were crewed by five men – a commander, driver, gunner, and two gun loaders. The vehicles had open-topped turrets, making it easy for TD crews to spot German tanks and quickly load and fire their cannon.54

A tank destroyer battalion had a headquarters company, a reconnaissance company, a medical detachment, and three tank destroyer companies, totaling about 650 men:55

• Tank Destroyer Battalion (Self-Propelled) o Headquarters Company (13 officers, 114 men) o Reconnaissance Company (6 officers, 122 men) o Medical Detachment (2 officers, 17 men) o 3x Tank Destroyer Companies (each 5 officers, 128 men)

The headquarters company provided command, communications, supply, maintenance, and medical evacuation duties. The reconnaissance company drove jeeps, motorcycles, trucks, Employment: Tank Destroyer Unit, FM 18-5. 18 July 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944, 3-9; and “tanks and armored cars,” War Department, Organization and Tactics of Tank Destroyer Units, FM 18-5. 16 June 1942. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1942, 8. 53 Combat doctrine, War Department, Tactical Employment: Tank Destroyer Units, 3-7. 54 M10 and M18 tank destroyers, Trewhitt, 144-145; and M36 description, Wwiivehicles.com. “United States’ M36 Gun Motor Carriage.” Accessed October 28, 2011. http://www.wwiivehicles.com/usa/tank-destroyers/m36.asp. 55 Organization, Tank Destroyer School. Functional Organization Charts, Tank Destroyer Bn, TDS-103. May 1943. Camp Hood, TX: Tank Destroyer School, 1943.

31

and M8 armored cars. Their job was to aggressively patrol and search for German tanks so that the tank destroyer companies could ambush them. The reconnaissance company had a pioneer platoon and three reconnaissance platoons:56

• Reconnaissance Company o Company Headquarters (2 officers, 21 men) o Pioneer Platoon (1 officer, 33 men) o 3x Reconnaissance Platoons (1 officer, 21 men)

The pioneer platoon cleared obstacles from the reconnaissance company’s path – including clearing mine fields and building bridges. They also created obstacles to force German tanks to move towards areas where TDs could ambush them. These included building road blocks, laying mine fields, and destroying bridges. The reconnaissance platoons were responsible for doing the battalion’s scouting. They were equipped with six 57mm anti-tank guns, which could fight German tanks, if necessary. They were also responsible for delaying and channeling German tanks towards planned ambush areas, in cooperation with the pioneer platoon. Their job was not really to fight, but to encourage German tanks to move towards tank destroyer companies lying in wait for them.57

The main fighting component of the battalion was the three tank destroyer companies. Self-propelled and towed tank destroyer companies were organized in the same way. Each company had three tank destroyer platoons, and each platoon had four tank destroyers and a command vehicle. The platoon was split into two sections, each with two tank destroyers:58

• Tank Destroyer Company (Self-Propelled) o Company Headquarters (2 officers, 22 men) o 3x Tank Destroyer Platoons (Self-Propelled) (each 1 officer, 32 men with 4x TD)

Once German tanks were sighted by tank destroyer crews, the TDs ambushed their enemies from camouflaged positions. Often, one platoon was deployed behind the other two platoons. The rear platoon opened fire first. Once the tanks maneuvered to get out of the platoon’s field of fire, they stumbled upon the other two tank destroyer platoons and were ambushed. The tank destroyer soldiers did not passively sit back and let the tanks attack them. Instead, they used aggressive tactics to try to encircle and destroy the attacking tanks. Two tank destroyer favorites were the ‘company end run’ and the ‘platoon hook and jab.’ In the company

56 Headquarters and reconnaissance companies, Tank Destroyer School, 3-11. 57 Pioneer platoon organization, Tank Destroyer School, 9-10; and role, War Department, Tank Destroyer Pioneer Platoon, FM 18-24. November 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944, 1-2. 58 Tank destroyer company organization, Tank Destroyer School, 12-13.

32

end run, one platoon ambushed German tanks to their front while the other two platoons drove around the side of the German tanks at high speed to ambush them. The platoon hook and jab was a similar maneuver – one section of TDs fired on the tanks while the other pair of TDs moved around the side of the tanks and opened fire.59

Tank destroyer battalions each carried a unique number. Companies were lettered, while platoons were numbered.60

What was my soldier’s job?

This is a list of the different ranks of soldiers in the battalion, along with their most likely job. Further research should help determine exactly what role your soldier played in his unit.61

Lt. Colonel: Commanded the battalion

Major: Was a staff officer or executive officer of the battalion Captain: Commanded a company or was a staff officer 1st Lieutenant: Executive officer of a company, a staff officer, or platoon leader 2nd Lieutenant: Commanded a platoon Master Sergeant: Senior NCO in the battalion and a role model for the men 1st Sergeant: Senior NCO in a company and served as a role model for the men Tech Sergeant: More senior executive officer of a platoon Staff Sergeant: Executive officer of a platoon Sergeant: Tank destroyer commander Corporal: Gunner or vehicle driver PFC/Private: vehicle crewman or gun crew

Tank Destroyer uniform patch.

59 Combat tactics, War Department. Tactical Employment of Tank Destroyer Platoon, Self-Propelled, FM 18-20. 9 May 1944. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944, 26-55, and Tank Destroyer Center. “Battle Plays for Tank Destroyers.” Undated. 60 Nomenclature, Tank Destroyer School. 61 Jobs, Tank Destroyer School, 2-4.

33

Armor Combat in Normandy

Armored divisions provided the U.S. Army with a powerful weapon for taking the fight to the German Army. Armored troops performed superbly throughout the fighting in Northwest Europe in 1944 and 1945. They were vital to the U.S. Army’s success in Normandy. Without armored troops, Operation Cobra, the battle for Falaise, and the pursuit across France would not have been the stunning successes that they were. In a typical armored division, 62% of casualties were armored infantrymen, 23% were tank crews. The other 5% was spread amongst the artillery and support troops.62

Though armored troops certainly did their fair share of fighting in Northwest Europe, they were not used to defend static positions for extended periods of time, as the infantry did. Armored troops were kept in reserve behind the front lines until needed for a particular mission. Then the division was moved to the front line to make their attack. The division attacked and pursued their enemies. Once an offensive was called off or halted, the armored troops were put back in reserve, to prepare for the next offensive. An infantry division would take over responsibility for guarding the territory captured by the armored troops. Despite these short breaks, American armor spent plenty of time on the front lines.

63

Tank crews had a difficult time fighting in Europe in 1944 and 1945. The American Sherman tank was quite vulnerable to German anti-tank weapons. Its armor simply was not thick enough to protect it from German shells and anti-tank rockets and it had a high profile, making it easy to spot and to hit. When the Sherman did get hit it often burned, because of poorly designed ammunition storage compartments. American soldiers called the Sherman ‘the Ronson,’ after a brand of cigarette lighter. Ronson’s advertisements boasted that “Ronson always lights the first time.” German units bristled with anti-tank weapons, each one capable of destroying a Sherman. The Germans even developed a portable, disposable one shot anti-tank rocket launcher called the panzerfaust. German squads tended to have two or three of these weapons. To make matters worse, tanks could not maneuver through the bocage. Instead, they had to either drive over bocage embankments – exposing their thin belly armor to German weapons – or use roads and other predictable routes where the Germans were sure to have anti-tank weapons. In July 1944 an American tank commander named Sergeant Curtis G. Culin found a way for tanks to cut through the bocage. Culin mounted metal shears to the front of his tank, which allowed the tank to break through the bocage embankment instead of having to drive over it. The ‘Culin device’ quickly

62 Operation Cobra and breakout, Blumenson; and casualty statistics, Doubler, 240. 63 Armor operations in Normandy, Houston, 197-282

34

spread throughout the Army’s tank battalions and armored regiments; tanks with the Culin device fitted to their hull were called ‘rhinos.’64

When German tanks were encountered, the situation got even worse. American tank cannons and anti-tank guns were not as powerful as their German counterparts. German guns could easily penetrate the armor of American tanks, while American tank crews generally had to maneuver for shots against the weaker side armor of the German vehicles. American tanks had to get within a few hundred yards to be able to penetrate the side armor of German heavy tanks like the Tiger and Panther. In contrast, German tank cannons and anti-tank guns could destroy a Sherman from 2,000 or more yards away – even from the front. Because of their lack of firepower, American tanks and tank destroyers often had to maneuver for side shots against the panzers. This was often difficult in the bocage country, and was made even worse by the Sherman tank’s inferior cross-country speed compared to German tanks. As a result, American armor often suffered heavily when they fought German tanks. 3rd Armored Division ordnance officer Belton Cooper estimated that German tanks had a 5:1 qualitative advantage over the American Sherman tank.

65

American commanders found that their best weapon against German tanks was the airplane. American fighter planes destroyed thousands of German vehicles during the fighting in Normandy. Diving down out of the sky, each fighter plane could hit German troops with a 500 pound bomb, eight explosive rockets, and machineguns. Each American division had a team of officers whose only job was to coordinate air attacks against German troops. When armored divisions attacked, they received additional assistance from American pilots. American fighter pilots flew Armored Column Cover (ACC) missions for armored troops. Each armored battalion or combat command had a radio link to a squadron of fighter planes circling overhead. The fighters scouted ahead of the tanks for German forces and attacked anything they found.

66

American armored infantry and field artillery units were also critical members of the team. Armored infantrymen provided vital support to the armored division by protecting American tanks from destruction and defending territory captured in tank attacks. American artillery quickly became the German soldier’s worst nightmare and the American soldier’s best friend. The artillerymen worked tirelessly to provide support to infantry and tank units in need of extra firepower against enemy defenses. American artillery fire was decisive in many battles

64 Sherman design characteristics, Cooper, 335-342; Ronson, Funding Universe. “Ronson PLC.” Accessed October 12, 2011. http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/Ronson-PLC-company-History.html; German anti-tank weapons, Gary Kennedy. “The German Grenadier Battalion, 1943-1945.” Battalion Organization during World War II. Accessed October 12, 2011. http://www.bayonetstrength.150m.com/German/Infanterie/german_grenadier_battalion%201943%20to%201945.htm; Culin device, Doubler, 45-46. 65 Armored combat in Normandy, Cooper, 15-95; and 5:1 advantage, Cooper, 337. 66 Air-ground support, Doubler, 63-86.

35

throughout the war, and certainly proved immensely helpful to American soldiers in Normandy. A British Army study conducted after the war showed that artillery was the main killer on the WWII battlefield:67

Weapon Casualties Artillery, mortars, aircraft bombs 75% Machineguns, rifles, anti-tank shells 10% Mines and booby traps 10% Other 5%

When American armored soldiers were not fighting, they were either moving somewhere, digging foxholes, or resting in them. Whenever an American soldier was going to be in one place for more than a few minutes, he took his shovel out of his pack and dug a six-foot deep hole for protection. Squads dug their holes in the same location, in the place that the platoon leader ordered them to dig. Two or three men shared a foxhole. Tank and tank destroyer crews dug a larger hole for everyone underneath their tank, for extra protection. Sometimes the unit was ordered to move again as soon as the men finished digging. Other times, a unit might be in one place for several days. If this occurred, the soldiers continued digging to connect the foxholes with each other to form a ‘slit trench.’ Soldiers tended to stay in their foxhole or slit trench unless they had a good reason to leave it – the foxhole meant safety and being outside meant being exposed to bullets and shells. One man in each foxhole was always on guard duty. The other man or men slept, read, wrote letters, ate, etc.68

Men learned to eat, drink, and sleep whenever they got a chance, because they never knew when they would have the next opportunity. Soldiers only got about three hours of sleep a night. They were woken up constantly by the need to take their turn as a guard, or by false alarms of enemy attacks by frightened comrades, or by the never-ending pounding of artillery. Soldiers used their helmet as their toilet and as their wash basin whenever the need arose. They went months at a time without bathing, except for a makeshift bath in a puddle of cold, muddy water. They went a week or more without shaving and they tended to have lice.

69

Soldiers had hot meals delivered to them by their company mess sergeant, who brought up pots of food in a jeep at night. Hot meals were not very common, however, and the combat

67 American artillery support, Doubler, 19-20; and distribution of casualties, Stephen Bull. World War II Infantry Tactics: Squad and Platoon. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2004, 6. 68 Foxholes and trenches, John C. McManus. The Deadly Brotherhood: The American Combat Soldier in World War II. New York: Ballantine Books, 1998, 71-73. 69 Sleep, McManus, 269; and hygiene, McManus, 76-78 and John Ellis. The Sharp End: The Fighting Man in World War II. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1980, 185.

36

soldier tended to survive on Army rations from his pack. They came in four different varieties. Armored troops tended to eat ’10 in 1’ rations, which were the most prized variety. The 10 in 1 ration came packaged in a large cardboard box and contained enough assorted foods for ten men to eat. Soldiers stored the boxes on the back of their tank or inside their halftrack or truck. The 10 in 1 ration was particularly prized because it provided soldiers with some variety, instead of the same lousy food day after day. The most common infantry rations were K rations and C rations, but armored soldiers generally did not have to eat those, since 10 in 1 rations were available and easy to carry in a vehicle. K rations came in a small cardboard box marked B, L, or D (for Breakfast, Lunch, or Dinner). Denis Huston of the 99th Infantry Division described the contents of the D box K ration: “The D box included a can of hash or some other mixture of food not readily identifiable by sight, smell, or taste, a candy bar, four cigarettes, sugar, Nescafe, and crackers or hardtack.” C rations were similar, but packaged in two metal cans. One can held food which the soldier cooked over a small stove he took out of his pack, and the other held assorted powdered drinks, coffee, crackers, cigarettes, sugar, candy, and toilet paper. The soldiers also were issued with D rations, which were very hard chocolate bars. They were intended for use in an emergency and a soldier could get a day’s calories from consuming only three or four of them. The D ration was bitter in taste and many soldiers became nauseous after eating an entire bar. Soldiers usually used their bayonets to shave a few scrapings of the bar (it was too hard to break with bare hands) into their canteens to make a chocolate drink.70

Combat soldiers tended to be resentful of soldiers who served in support roles in the rear area, in more comfortable and less dangerous living conditions. Many combat soldiers felt that they had more in common with the Germans than they did with the ‘rear echelon commandos’ in the rear. They also tended to be distrustful of outsiders. The combat soldier’s world became very small – just the other guys in the squad, the hole he lived in, and the field and hedgerows surrounding his home. They lived on rumors and wild stories, hoped that everyday brought a letter from home, and – if they dared – dreamed of the day when the war would end and they could all go home. His comrades – whether he liked them or not – became his family. If a soldier got a package from home, he shared its contents with the rest of the group. Outsiders were treated with cold indifference until they proved themselves worthy of being admitted to the group.

71

70 Rations, McManus, 16-30; and “the D box included,” Denis Huston quoted in McManus, 24. 71 Attitudes, McManus, 237-305.

37

Resources

Books