Sodium and potassium contents of low salt and unsalted foods and their regular equivalents

-

Upload

heather-greenfield -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of Sodium and potassium contents of low salt and unsalted foods and their regular equivalents

JOURNAL OF FOOD COMPOSITION AND ANALYSIS 2,245-259 (1989)

Sodium and Potassium Contents of Low Salt and Unsalted Foods and Their Regular Equivalents

HEATHERGREENFIELD' AND CAROLYNY. LOONG

Department ofFood Science and Technology, University oj’New South Wales, P.O. Box 1, Kensington, New South Wales 2033, Australia

Received April 14, 1989, and in revised form November 6, 1989

This study compared low salt and unsalted (LS/lJS) foods with their regular counterparts in terms of sodium and potassium contents. In almost all cases sodium was >50% lower in the low salt foods, and in most cases z 80% lower in the unsalted foods. In some products, potassium levels were also altered significantly, but the Na:K ratio was always lower in the LS/US foods. Comparison with a 1982 study indicated that the sodium contents of regular foods, except for potato chips, had not declined. o 1989 Academic press, IIK.

INTRODUCTION

In Australia, as in many other Western countries, there is increasing concern about the high rates of hypertension in the community due to its relationship with morbid- ity and mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease (Better Health Commission, 1987). Efforts to control the emergence of hypertension include a dietary goal of re- duced salt consumption (Langsford, 1979) with dietary guidelines promulgated sub- sequently (Commonwealth Department of Health, 198 1) advising the community, among other things, to read product labels for guidance regarding content of salt and other sodium-containing ingredients. Later there were criticisms of the salt levels in Australian foods (National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC], 1984) and our own studies had suggested that the range of salt contents measured in differ- ent brands of particular foods indicated that a modest reduction to the lower end of the range analyzed would be feasible (Maples et al., 1982). Under the impetus of the various reports, large numbers of foods began to proliferate in the market with labels claiming low or reduced salt contents, or no added salt. A study was therefore under- taken to quantify the potential nutritional benefit offered by foods so labeled com- pared to those of their regular equivalents. The study also provided an opportunity to ascertain whether there had, in fact, been any reduction in the sodium content of these regular foods since the previous study (Maples et al., 1982). Further, the study aimed to assess whether the low salt or unsalted foods varied in their potassium con- tents in comparison with their regular counterparts, since potassium addition was permitted by the relevant food regulations for some salt-modified products.

Foods

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A preliminary survey was carried out to identify the types and brands of low salt (LS) foods (here defined as those with labels claiming low salt, reduced salt, or similar)

’ To whom all correspondence and reprint requests should be addressed.

245 0889- 1575/89 $3.00 Copyright 0 1989 by Academic Press. Inc. All rights of reproductmn in any form reserved.

246 GREENFIELD AND LOONG

and unsalted (US) (or salt-free or no added salt) foods available in supermarkets in Sydney, Australia, in January 1985. Collectively these foods are described as LS/US in this paper. The regular counterparts of these foods (i.e., equivalent foods with salt listed as an ingredient, or equivalent foods with no LS/US claim and with no ingredi- ent lists) were also identified. From the large number of products available those considered most important within the food supply and selected for study were (Table 1): cereal products (breads, breakfast cereals, savory crackers, and Swedish-style crisp- breads); spreads (butter, margarine, peanut butter); snack foods (nuts, potato chips); soups (packet mix and canned concentrates: chicken, chicken noodle, tomato, mush- room); canned vegetables (peas, corn (whole kernels), tomatoes); tomato products (juice, sauce, paste); canned fish (tuna, pink salmon).

The foods were purchased, group by group, for study in the period May to Decem- ber, 1985. For food types of which two or more brands were available, a single pur- chase was made of each brand. Comparisons were thus n brands X 1 purchase of LS/ US foods versus n brands X 1 purchase of regular foods. For food types of which only one brand was available, four purchases were made each from different outlets and bearing different batch codes and use-by dates. Comparisons were thus 1 brand X 4 purchases of LS/US food versus 1 brand X 4 purchases of regular food.

Analytical Method

Each food purchase was homogenized using a domestic food processor (Breville Kitchen Wizz) and analyzed individually in duplicate for sodium and potassium by means of dry ashing and solubilization in hydrochloric acid, followed by atomic ab- sorption spectroscopy as described by Wills et al. (198 1). Canned vegetables and fish were drained prior to analysis. When duplicates disagreed by >5% of their mean further replicate analyses were performed and all replicate values included in the calculation of the final mean. Reliability of the analyses was also assured by use of NBS certified reference material bovine liver 1577a (Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC), 50.044-50.045, 1984).

Statistical Methods All statistics were performed on the raw data. Where a direct comparison could be

made of two versions of the same brand (e.g., low salt and regular versions) a t-test was performed, while when three versions existed (e.g., regular, salt-reduced, and no added salt versions) analysis of variance was used to ascertain statistically significant differences at the 5% level. Tukey’s honestly significant difference was used for pair- wise comparisons within the analysis of variance. For comparisons of two or three complete groups of products, t-test and analysis of variance were used, respectively, with the Scheffe procedure used for pairwise comparisons within the analysis of vari- ance. Statistical procedures were as outlined by Roscoe (1975). In cases where only one LS/US product was available, comparison with the group of regular products was by nonstatistical visual inspection only.

RESULTS

Analytical data are shown in Tables 2-7, rounded according to journal policy. Na: K ratios are shown on a millimole basis calculated from the raw data.

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM IN LOW-SALT AND UNSALTED FOODS

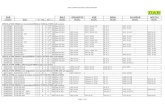

TABLE 1

BRANDNAMESANDLABELCLAIMSOFLOWSALTANDREGULARFOODS STUDIED

Food groups andtypes

cereal umducts Wholewheat breads

Multigrain breads

Crunchy granola

Regul=

Fabulous Fibre Wheat Fielders OMill Riga Tip Top Wholemeal Tip Top Wheatmeal Fanhoffen ButtercupGoGrain Buttercup Kibblewheat Fielders Fielders Kibble’n’Rye Rogenbrot Siebers Tip Top VOg& Weight Watchers CWh c&s Plain wrap Fabulous Farmland Purina White Wings

Low salt or No added salt, salt-reduced unsalted or salt-free

Buttercup Osloaf Riga Rig.3 Ritikin

Tip Top Hyfibe

BakehouseGoldenGrti Siebers

Farmland Grain Mill Purina Hi Fibre Pwbla Swiss Fomula

Lc-salt Premium

c&s Plain Wrap+ Fabulous+ Grain Mill+ No Frills+ Purina*+ RyVita Vitawheat

Swedish-style crispbread

crackers

Ryvita Vitawheat Premium

Soreads Butter Allowrie

Peanut butter

Devondale Fabulous Farmland MCMahon’S No Frills western star NOPXI ASIX% C&s Plain Wrap Daffodil DiXibell Eta Flora Golden Pastures Meadowlea Miracle MIS McGregor Praise Spreadwell Stork Weight Watchers BaSCO C&s Plain wrap DaHOdii Eta Farmland

Allowrie Allowlie NOrcO

Flora Meadowlea

Betel Smdew

Fmnland sanitarium

The mean sodium and potassium values of NBS SRM 1577a bovine liver obtained in this study were 250 f 6 and 980 f 10 mg/lOO g, respectively (10 determinations). These results compared favorably with the certified values of 243 f 13 and 996 f 7 mg/ 100 g, respectively.

248 GREENFIELD AND LOONG

TABLE I-Continued

Food groups and types

Regular No added salt, unsalted or salt-free

Kraft PDF Sanitarium

Snackfoods Cashews Eta

Peanuts

rotato chips

a Chicken, canned

conCentiates

Chicken, packet mix

Chicken noodle, packet mix

cup mix

Tomato canned concentrates

Mushroom packet mix

Farmland Nobbys No Frills Planters sanitarium Amens Cole3 Plain Wrap Daffodil Eta Fabulous Farmland Nobbys No Frills PDF Planters Amotts Ruftles Farmland Wrinkles smiths crisps No Frills

campbells Heinz Kia-ora PMU ROSl?!J~ Conlinental

M=g@ c&s Plain Wrap COlhV3lt.d No Frills Weight Watchers Anchor c&s Plain Wrap Continental Fabulous Famland

M=ggi No Frills San Remo Continental No Frills campb& c&s Plain wrap Fabulous Farmland Heinz Kia-ora No Frills PMU Rosella continental

Planters Farmland

Planters

Amotts Thins smiths Lites

Rosella

Continental Trill-l so Slim

continental

H&U

Heinz

Canned veeetables and tomato moducts Peas, canned c&s Plain Wrap

Edgell Fabulous Farmland Golden Circle

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM IN LOW-SALT AND UNSALTED FOODS 249

TABLE I-Continued

Food groups

ami ‘YP=

Corn, whole kernels. canned

Tomatoes, canned

k+=

Mountain Maid No Frills Edgell Fabulous Farmland Golden Circle No Frills WC Edgell Farmland

%lF

No added salt, unsalted or salt-free

Farmland

Tomato sauce Coles Plain wrap Fabulous Farmland Fountain Heinz lxL No Frills PMU POPS Rosella Fountain LeggOS

Ardmona Ed@ Fabulous Farmland Goulboum Valley La Gina LetOtl?i Abundant Earth Farmland Fountain Rcwlla

Tomato paste

Tomato juice

Canned fish Pink salmon

TUU

Beti CampbellS

Fabulous Farmland Goulbam valley H&Z Heinz Big Red Quelch

MY AIICh‘X Coles Plain Wrap Farmland John West Paramount c&s Plain Wrap Fabulous Farmland GP33WXS John West S.&D1 seahaven seakist

Campbells* COles’ F&d*+ lXL+ L&ma No Frills+ Tom Piper+ Letma Farmland

Farmland

Farmland

*No added salt label claim. t No ingredients listed.

Cereal Products

The mean sodium and potassium contents and Na:K ratios of breads, breakfast cereals, crispbreads, and savory crackers studied are shown in Table 2. LS/US breads

250 GREENFIELD AND LOONG

TABLE 2

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM LEVELS, AND Na:K RATIOS OF CEREAL PRODUCTS

(MEANS IfI STANDARD DEVIATIONS)

Food

&a&

No. of brands

No. of purchases per brand

Sodium Potassium Na:K ratio blg/1OOg) hg/loog) hmol basis)

Wholewheat regular 5 low salt 3 salt free 1

MUltipi~ regUlL?I 10 low salt 2

s crunchy granola

Farmland regular 1 no added salt 1 All brands resul= 6 no added salt 4

Natural bran no ingredients

listed 4 no added salt 1

CrisDbreads Crispbread

Ryvita regular 1 no added salt 1 Vitawheat resula 1 no added salt 1

crackers Premium regular 1 salt-reduced 1

4

4 4

1+ 1+

4

4 1000+4Za 120+12a 4 ao+d 110+11a

460+59= 200+12oc

21~7~ 1100+230* 0.03 32+4* 950+49* 0.06

530i11a 430+7a 6z+9d 370+17d

510+53= 594

410+14a so&

230+3Za 310+160a 440+12*

210+30a 300+240”

300+24a 330+10a

300+83a 400+100=

3.3 1.1 0.1

3.8 0.8

1.6 0.09

1.0 0.06

2.1 0.3

2.1 0.3

14.8 8.1

Note. Within pairwise comparisons of regular and LS/US equivalents; a+no significant difference, P > 0.05; 8*bsignificant difference, P < 0.05; a.cP < 0.0 1; a.dP < 0.00 1.

* No statistical evaluation as replicates not strictly comparable. t Except for the brands shown, studied individually in four replications: mean value used in group

statistical evaluation.

identified on the market were mainly whole wheat (regular, low salt, and salt-free) and multigrain regular and low salt varieties. For both whole-wheat and multigrain breads the low salt versions had less than half of the sodium of their regular equiva- lents (P < 0.01) while for salt-free whole-wheat bread inspection of the data shows that this product has about one-twentieth of the sodium of regular whole wheat. So- dium in bread is derived from flours, grains, yeast, and milk solids but the main source in regular breads would be salt added at about 1 - 1.4 g/ 100 g for functional purposes (e.g., to control fermentation, to strengthen gluten of doughs, and to control water absorption and for flavoring).

The processing functions of salt can be substituted by potassium salts and labels indicated the use of potassium chloride in the salt-free whole-wheat bread and some of the low salt breads. However, as a group, low salt breads did not differ in their potassium content from regular breads, due to the large range in potassium contents observed. Inspection of the data for salt-free whole-wheat bread indicated that this

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM IN LOW-SALT AND UNSALTED FOODS 251

product has almost double the potassium of regular whole wheat, thus effecting a dramatic improvement in Na:K ratio in the salt-free bread.

Within the breakfast cereals there were highly significant greater than lo-fold differences (P < 0.00 1) in sodium content between regular and no added salt crunchy granolas, and no difference in potassium contents. The main source of sodium in regular crunchy granolas would have been salt as other ingredients such as rolled oats, raw sugar, honey, dried fruits, vegetable oil, and nuts are low in sodium (Paul and Southgate, 1978). All five brands of natural bran available had no ingredient lists and one brand (Purina) bore a “no added salt” claim. There were no differences in either sodium (low in both cases) or potassium contents between Purina “no added salt” brand and the other brands. The label “no added salt” was therefore technically cor- rect but redundant. Potassium contents of the breakfast cereals were high as would be expected of the intrinsic cereal, fruit, and nut ingredients (Paul and Southgate, 1978); Na:K ratios were thus very low in the salt-free versions.

Two savory Swedish-style crispbreads and one savory cracker product with regular and LS/US equivalents were identified on the market. The two crispbreads with no added salt had about a tenth of the sodium of their regular counterparts (P < 0.00 1) and also had slightly but significantly lower potassium levels. The salt-reduced cracker had about half of the sodium of the regular cracker but it should be noted that this sodium content was very similar to that of regular crispbreads. Potassium contents did not differ between the two types of cracker, but were less than half those of the crispbreads; thus Na:K ratios were more favorable in crispbreads than in crackers.

The ingredients which would contribute sodium to regular crispbreads and crack- ers include salt, baking powder, milk products, and yeast. Baking powder adds texture and volume and salt controls fermentation and water absorption rates; however, a major reason for using salt is flavor. There was no evidence of the use of potassium salts in the LS/US crispbreads and crackers.

Spreads

The results for butter, margarine, and peanut butter are shown in Table 3. For each product type the low salt variety had about half of the sodium of the regular varieties (P < 0.01 or P < 0.00 l), while unsalted, no added salt, or salt-free varieties had 20% or less of the sodium content of the regular types (P < 0.001). Regular butter and margarines had similar sodium contents. Salt is added to butter and margarine as a preservative and for flavoring (Anderson, 1954). In peanut butter, salt is used mainly for flavor (Woodroof, 1983).

Potassium contents also varied within the butters and margarines, the low salt vari- eties having about three-quarters of the potassium of the regular types (P < 0.001) and the unsalted or salt-free types having about one-quarter of the potassium of the regular type. The reason for the differences is not clear except that salt-free margarines were also “milk-free” and this would have affected potassium levels. Nevertheless Na: K ratios were improved by reducing or removing salt. Overall the potassium contents of regular butters and margarines were very low (~25 mg/lOO g), while that for the peanut butter was high (-600 mg/ 100 g) due to the content of nuts.

252 GREENFIELD AND LOONG

TABLE 3

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM LEVELS, AND Na:K RATIOS OF SPREADS (MEANS f STANDARD DEVIATIONS)

hod No. of No. of sodium Potassium Na:K ratio brands purchases (mg/lOOg) (mg/lOOg) (mm01 basis)

per brand

8 1 2

1

14 2 2

1

8 2

4 4

4 4

I+ 4

7oo+lood 340~20~

1a+2f

7oo+lzod 19~2~

700+15od 340+20*

19+2e

no+w’ 25+1= 48.6 400+7e 26&3a 26.3

no& 20k3a 61.3 390~2~ 1l3+5” 37.1

700+140a 22+7= 57.6 4oo+7b 22&i= 30.8

6+lc <l >3.8

41o+39d 21@

so+zzd 15+3e

500+11od 18~6~

2o+2d 15+2e 5+1f

60.9 38.3

6.1

2o+ld 57.7 5+1e 6.4

21+3d 15+2* 5+1e

55.1 38.3

6.4

630+48= 630+13a

64l0+30a 630+10=

600&G 630+11=

1.1 0.06

1.0 0.04

1.3 0.05

Note. In pairwise or three-way statistical comparison of regular and LS/US equivalents; Yto significant difference, P > 0.05; “,b,csignificant difference, P < 0.0 I ; d*‘and d,c.fP < 0.00 1.

* No statistical evaluations as replicates not strictly comparable. t Except for the brands shown, studied individually in four replications; mean value used in group

statistical evaluation.

Snack Foods

The sodium and potassium levels in cashews, peanuts, and potato chips are shown in Table 4.

The sodium content of Farmland cashews was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the no added salt type than in the regular type, while they did not differ in their potassium values, which were high in both cases. By inspection these results were also found when all six regular brands of cashews were compared with the single no added salt brand, the regular brands having 20 times the sodium content of the no added salt brand. Low salt Planters peanuts had less than half (P < 0.0 1) the sodium content of the regular version while “no added salt” Farmland peanuts had more than 30 times less sodium (P < 0.001) than regular Farmland peanuts. However, regular Farmland peanuts had about 40% less sodium (P < 0.05) than regular Planters pea- nuts. When all brands of peanuts were compared, by inspection the salted types had

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM IN LOW-SALT AND UNSALTED FOODS 253

TABLE 4

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM LEVELS, AND Na:K RATIOS OF SNACK FEUDS

(MEANS f STANDARD DEVIATIONS)

Food No. of No. of Sodium Potassium Na:K ratio brands purchases (mg/lOOg) (mg/loog) (mm01 basis)

per brand

Cashews

1

1

10

1 1

1

5 2

4 4

1+ 4

I+ 400+160a 13OO_+?lod 4 360+45= 1300+110~ 4 26+5* 99oc92’

3E30+14a 1 s+2c

400+170* l&2’

360+22= 10+1C

610213” 630+16”

1.0 0.03

640+42a 610 +sa 1.8 24o+18b 670&Ba 0.6

500+140* 540&Y 1.6 240+1@ 670+23a 0.6

lo& 630~16~ 0.03

610+81a 4oo+d

400+150a 330+2Sa

220+14” 26+5=

590+12a 610524”

1.1 0.05

600+22* 610+24*

1.1 0.05

1500+130~ 0.7 1000~190= 0.6

140094a 13mw34a

1100+42a 980+92a

0.5 0.4

0.4 0.04

0.5 0.5 0.04

Note. In pairwise comparisons of regular and LS/US equivalents; a%o significant difference; “,bsignificant difference, P < 0.0 1; a.cP i 0.00 1.

* Statistical evaluations not performed as replicates not strictly comparable. t Except for the brands shown, studied individually in four replications; mean value used in group

statistical evaluation.

about double the sodium of the low salt type, and more than 50 times the sodium content of the no added salt type. Potassium levels were high and were similar in regular, low salt, and no added salt peanuts.

The wide range in sodium contents analyzed in nuts would be due to different amounts of salt adhering to the nut surfaces during processing handling as this de- pends on the roasting methods and oils used and on salt crystal sizes and shapes (Woodroof, 1983).

For potato chips there were two brands (Smiths and Arnotts) which had regular and lightly salted equivalents. In the case of Arnotts there was no difference in sodium content between the two types, while for Smiths the lightly salted type had about two- thirds of the sodium content of the regular type (P < 0.001). For Farmland the no added salt type had about one-tenth of the sodium content of the regular type (P < 0.00 1). When all brands were compared, lightly salted chips conferred no advan- tage over regular chips in terms of sodium content, while the no added salt brand did.

254 GREENFIELD AND LOONG

TABLE 5

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM LEVELS, AND Na:K RATIOS OF SOUPS (MEANS + STANDARD DEVIATIONS) No. of Sodium Potassium Na:K ratio Food No. of

brands purchases per brand

hlg/100g) hlg/100@ (mm01 basis)

g&@&l Continental (packet mix) P@ElI 1 salt-reduced 1 Heinz kanned concentrate) regular 1 no added salt 1 Rosella kanned concentrate) regular 1 salt-reduced 1 All brands 1eglllCU 11 salt-reduced 4 no added salt 1

Chicken noodle Continental (packet mix) regular 1 salt-reduced 1 All brands Eglh 10 salt-reduced 2

Tomato Heinz kamed concentrate) regular 1 no added salt 1 Rosella kanned concentrate) regular 1 salt-reduced 1 All brands Wpl.31 9 salt-reduced 1 no added salt 1

MUShIWXl Continental (packet mix) regular 1 salt-reduced 1

4 360+7a 4 170#

4 390+11a 4 100+14c

4 400+13” 4 180?9C

1+ 380*74= 1+ zoo&’ 4 100+14*

4 400@ 4 170+6c

1+ 450+47a 4 z4o+d’

54t3a 98~5C

11.4 3.0

90@ 7.4 s3+2b 3.2

76i6a 8.9 74+3” 4.2

53219” 12.0 72i21a 4.8 53?2= 3.2

11+2a 60.7 14,2a 21.1

28.3 19.9

4 300+12a 4 36+lc

4 410~6~ 4 180+8C

1+ 350*51* 4 180+8* 4 3621’

170+6a 170+s=

3.0 0.4

240~7~ 230+3=

3.0 1.3

170+36’ 230+3* :7o+a’

3.5 1.3 0.4

4 310+1P 150+1P 3.5 4 15ot99c 140cBa 1.8

Note. In pairwise comparisons of regular and LS/US equivalents; a%o significant difference, P z 0.05; “.bsignificant difference, P i 0.0 1; “,“significant difference, P < 0.00 1.

* No statistical evaluation as replicates not strictly comparable. t Except for the brands shown, studied individually in four replications; mean value used in group

statistical evaluation.

However, sodium contents differed significantly (P < 0.05) between regular types of potato chips according to the ranking Smiths > Arnotts > Farmland. Salt is added to potato chips for flavor purposes only. Potassium contents were very high and did not differ between regular chips and their LS/US equivalents; however Farmland regular chips had a lower potassium content (P < 0.05) than did the other brands. The very low Na:K ratio of chips is of interest given the criticism which has been leveled at the salt content of these products.

soups

Results for soups are given in Table 5. On the basis of comparisons within individ- ual brands or within soup-type groups sodium levels were significantly lower (P < 0.0 1 or P < 0.00 1) by about half in the salt-reduced varieties compared with those

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM IN LOW-SALT AND UNSALTED FOODS 255

in the regular varieties. No added salt varieties by inspection were much lower in sodium than regular varieties having about one-tenth of the sodium. When regular soups were compared, sodium levels were similar between chicken, tomato, and mushroom, with chicken noodle somewhat higher in sodium. The main source of sodium in soups would be salt added for flavor with monosodium glutamate, hydro- lyzed vegetable protein and nonfat milk solids also contributing. These ingredients would have been responsible for the fact that no added salt soups were somewhat higher in sodium than other no added salt products analyzed in this study. Potassium contents did not vary among soup types on the basis of salt label, except for Continen- tal chicken soup which had about twice as much potassium in the salt-reduced variety compared than in the regular variety (P < 0.00 1). This was possibly due to the use of more vegetables in the former, according to the ingredient listing. No potassium salts were included in this listing. Potassium levels on the whole appeared to be about 1 O- 20 times higher in tomato and mushroom soup than in chicken and chicken noodle presumably due to their vegetable base. In terms of Na:K ratio, the vegetable soups generally offered a nutritional advantage over the chicken soup types.

Canned Vegetables

The results for canned vegetables (Table 6) show that the no added salt products were dramatically lower in sodium than the regular products (P < 0.00 1 where appli- cable). Sodium levels appeared to be unrelated to vegetable type and were solely at- tributable to the brine in which the regular products were canned despite draining prior to analysis. Potassium levels did not vary on the basis of salt label but appeared to be higher in canned tomatoes than in canned peas and sweetcorn.

Tomato Products

As Table 6 shows, no added salt tomato sauce and tomato juice were significantly (more than 20-fold) lower in sodium contents than their direct brand regular equiva- lents (P < 0.00 1) and also in group comparisons (P < 0.00 1 or by inspection). How- ever, in the case of tomato pastes there were three types available. There were two brands with salt listed as an ingredient and five brands with no ingredients listed of which one (Farmland) claimed “no added salt.” The Farmland products did not differ in sodium or potassium content between the two label types, so here, as for the similar case for natural bran, the no added salt claim was redundant. The regular tomato pastes had significantly higher (P < 0.001) sodium contents than the other types, but did not differ from them in potassium content. Sodium would have been added for flavor to the regular types of all three tomato products (paste, juice, and sauce). Potassium levels did not vary with salt label; their ranking was paste > sauce > juice, presumably reflecting the amount of indigenous tomato present.

Canned Fish

No added salt canned pink salmon and canned tuna had about one-quarter of the sodium contents of most regular equivalents (Table 7) but did not appear to differ in sodium content on the basis of fish type. Sodium would have been contributed by brine used for canning despite draining prior to analysis. Potassium levels were sig- nificantly higher in a brand of no added salt canned pink salmon than in its regular

256 GREENFIELD AND LOONG

TABLE 6

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM LEVELS, AND Na:K RATIOS OF CANNED VEGETABLES AND

OF TOMATO PRODUCTS (MEANS + STANDARD DEVIATIONS)

Food No. of No. of Sodium Potassium Na:K ratio brands purchases (mg/100@ (mg/l@ogl (mm01 basis)

per brand

CaMed peas

salt clahn Tomato sauce

Farmland

regular no added salt Fountain

regular no added salt R04la

resul= no added salt AU brands regular no added salt

Tomato DaStC?

Farmland no ingredients listed no added salt All brands

regular no ingredients listed no added salt

Tomato i&e Pam&and

regular no added salt AU brands

regul= no added salt

4 4

1+ 4

4 4

1+ 4

4 4

4 4

l+

1+

4 4

4 4

4 4

l+ 4

4 4

1

1+ l+

4 4

1+ 4

230+lla 4+lb

290+42* 4+1*

150g1a 150+4a

130+20’ 15024.

2.6 0.04

3.8 0.04

2~30516~ 110+5a 3+lb uxl+sa

270+32* 3;’

120+14* 100+5*

4.4 0.05

3.8 0.05

230+17a lgczb

220+12a 210~7~

1.8 0.2

240+27a lo++’

280+79a

15+6b

210~16~ 220215”

220215’

210+2oa

1.9 0.08

2.1

0.1

920+43= 18+1”

450+30a 430214a

3.4 0.07

840+1@ g+lb

5OOfP 450+13a

2.9 0.03

990+2P 394’

450+27= 48&19=

3.7 0.1

1000+170a z6+eib

410+60a 470+33”

3.9 0.1

31+7a 38+2a

53o+21b

990+35= 930+4P

0.05 0.07

1000+110” 0.95

1000+110~ 930?79”

0.07 0.07

190+10a iylb

220+15= 210~5~

1.5 0.06

280+6d 210& 2.3 7+1* 210+5* 0.06

Note. In pairwise or three-way comparisons of regular and LS/US equivalents; %o significant difference, P > 0.05; asbsignificant difference, P < 0.00 I.

* No statistical evaluations as replicates not strictly comparable. t Except for the brands shown, studied individually in four replications; mean value used in group

statistical evaluation.

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM IN LOW-SALT AND UNSALTED FOODS 257

TABLE 7

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM LEVELS, AND Na:K RATIOS OF CANNED FISH (MEANS + STANDARD DEVIATIONS)

Food No. of brands

No. of purchases per brand

Sodium Potassium Na:K ratio (mg/10og~ (mg/mJg) (mm01 basis)

1 4 400+16 30029” 2.2 1 4 110+7b 290+19a 0.6

6 1+ 410+47* 320+26* 2.2 1 4 110?7’ 290+19’ 0.6

1 4 410+3Za 170@ 4.9 1 4 a& m+lob 0.5

8 1+ 400+100* 210c30’ 3.2 1 4 82+7’ 280+10* 0.5

No&. For pairwise comparisons of regular and LS/US equivalents; a%o significant difference, P > 0.05; “,bsignificant difference, P < 0.00 1.

* No statistical evaluation as replicates not strictly comparable. t Except for the brands shown, studied individually in four replications.

equivalent (P < 0.001). Possibly brine used for canning the regular product drew water and solubilized potassium from the fish flesh (Jason and Kent, 1980). Potas- sium levels appeared to be higher in canned pink salmon than in canned tuna.

DISCUSSION

In New South Wales, the state of Australia in which the foods for this study were bought, there was no regulation at the time covering the terms “no added salt,” “un- salted,” or “salt free.” However, there was provision in the New South Wales Pure Food Act ( 1982) for foods to be categorized as “special dietary low sodium foods,” i.e., as foods in which the ingredients containing sodium, or the sodium contents of one or more ingredient, were restricted. Such foods were required to bear the name “low sodium (name of food) special dietary food” on the label together with the so- dium content in milligrams per 100 g. The sodium content was required not to exceed 120 mg/ 100 g or half the sodium content of the regular product. The regulation per- mitted the replacement of sodium ingredients by potassium and required in this case the potassium content to be stated in milligrams per 100 g. All of the foods studied which bore the low sodium special dietary food appellation stated the sodium content as required and the analytical data obtained showed close conformity with the legisla- tion. This also applied to cases in which potassium content was declared on the label.

In September 1985, toward the end of the study, a new regulation was inserted into the Act stipulating that the words “no added salt, ” “unsalted,” or similar terms could not be used unless both the food andits ingredients contained no added salt. Recently the legislation was amended again to provide that “no added salt,” “salt free,” or “unsalted” covered no added sodium compounds as well as salt. Had such regula- tions taken effect at the time of the study, the foods described as “no added salt” or “unsalted” would have met the requirements, with the possible exception of soup,

258 GREENFIELD AND LOONG

Further, the foods described as salt-reduced, lightly salted, or similar (which is not covered by legislation) on the basis of the analytical data were much lower in sodium content compared with their regular equivalents except for potato chips.

A brand of natural bran and a brand of tomato paste whose labels stated “no added salt” did not differ in sodium content from the equivalent products not so labeled and which, in fact, bore no ingredient lists. The label was technically correct in that no salt had been added and ingredient lists were not required on the other version (which could equally well have borne the “no added salt” claim) since the food in each case comprised only the one identified product (natural bran and tomato paste, respectively). In these cases the manufacturers appeared to be utilizing the no added salt label opportunistically to draw attention to the low indigenous sodium content of a regular product.

“Lightly salted” potato chips as a group were not lower in sodium than the regular products partly as a function of the wide variety of sodium contents observed. This may have reflected an ambivalence in the snack food industry at the time since regu- lar potato chips were among the few products which were generally lower in sodium than they had been in the earlier study (Maples et al., 1982), suggesting some industry sensitivity to criticism of the sodium content of snack foods. The only other food which may have declined in salt content compared to a previous study (Dale, 1979; 663 mg sodium per 100 g) was canned tuna. However, the brand in the previous study was not stated and the tuna may have been analyzed along with the brine in that earlier study.

On the basis of this study most foods, labeled as low salt or salt-reduced, had about one-half of the sodium content of their regular equivalents while salt-free or unsalted foods provided less than one-fifth. As such, LS/US foods offer a genuine nutritional advantage to consumers concerned about salt intake who utilize the label informa- tion to guide product choice as advised in the dietary guidelines (Commonwealth Department of Health, 198 1).

The benefit to Australian consumers would increase if white bread similarly modi- fied were widely available as bread has been shown to be the major source of dietary sodium intake in Australia (Greenfield et al., 1984) and white bread is the type pre- dominantly consumed (Cashel et al., 1986).

The findings of this study conflict with our study of foods with a “no added sugar” or similar label claim. In that study, comparisons with respect to sugar content were obscured by the indigenous sugars present in foods such as fruit juices (Ford and Greenfield, 1988) so that the no added sugar foods were not necessarily lower in sugar.

Potassium was higher only in the salt-modified breads as a group, and potassium salts were apparently therefore not in wide use as salt substitutes. Potassium was also higher in one brand of salt-reduced chicken soup possibly due to the use of more vegetables in the product. It was also higher in canned pink salmon with no added salt possibly due to the potassium-preserving effect of water compared to that of brine as a canning medium. There may, therefore, be secondary benefits in reducing the salt contents of processed foods.

Overall the results suggest that the response of the Australian food industry to criti- cism of salt contents of foods has been the production of salt-modified alternative products. There was little evidence of a reduction of the salt contents of regular foods over time (i.e., since 1982). LS/US foods provide only a very low percentage of sales and therefore are unlikely to be making a major impact on community sodium in-

SODIUM AND POTASSIUM IN LOW-SALT AND UNSALTED FOODS 259

takes in general. There is a need for periodic monitoring of sodium contents of Aus- tralian foods in view of the continuing emphasis of health authorities on the need to reduce sodium intakes nationally (Better Health Commission, 1987) and the adop- tion by federal and state governments of nutrition, and of hypertension, as two of the five priority areas for action to improve health for all Australians (Health Targets Implementation Committee, 1988).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C. Y. L. was supported by a scholarship provided by McDonald’s Family Restaurants. The advice of R. B. H. Wills is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, A. J. (I 954). Margarine. Pergamon, London. Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) (1984). Ojicial Methods ofAnalysis of the Association

of Ofhcial Analytical Chemists, 13th ed. AOAC, Washington, DC. Better Health Commission (1987). Towards Better Nutritionfor Australians. Australian Government Pub-

lishing Service, Canberra, Australia. CASHEL, K., ENGLISH, R., BENNETT, S., BERZINS, J., BROWN, G., AND MAGNUS, P. (1986). National

Dietary Survey of Adults: 1983. No. 1. Foods Consumed. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, Australia.

Commonwealth Department of Health (198 I). Dietary guidelines for Australians. J. Food Nutr. 38, 1 I I. DALE, N. E. (1979). Sodium and potassium content of some Australian foods and beverages. Med. J. Aust.

2,354. FORD, N., AND GREENFIELD, H. (1988). Potential effectiveness of the dietary guidelines for reduced sugar

consumption: A case study of foods with no added sugar. Food Technol. Aust. 40,27 I. GREENL~ELD, H., SMITH, A. M., MAPLES, J., AND WILLS, R. B. H. (1984). Contributions of foods to

sodium in the Australian food supply. Hum. Nutr. Appl. Nutr. 38A, 203. Health Targets Implementation Committee (1988). Health for all Australians. Commonwealth Depart-

ment of Community Services and Health, Canberra, Australia. JASON, A. C., AND KENT, M. (1980). Physical properties and processes. In Advances in Fish Science and

Technology, (J. J. Connell, Ed.), Fishing News Books, Farham. LANGSFORD, W. A. (1979). A food and nutrition policy for Australians. Food Nutr. Notes Rev. 36, 100. MAPLES, J., WILLS, R. B. H., AND GREENFIELD, H. (1982). Sodium and potassium levels in Australian

processed foods. Med. J. Aust. 2,20-2. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (1984). Report ofthe Working Party on Sodium

in the Australian Diet. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, Australia. New South Wales Pure Food Act (1982) amendments. NSW Government Printer, Sydney. PAUL, A. A., AND SOUTHGATE, D. A. T. (1978). McCance and Widdowsons’s The Composition ofFoods,

4th ed. HMSO, London. ROSCOE, J. T. (1975). Fundamental Research Statisticsfor the BehavioralSciences, 2nd ed. Holt, Rinehart

and Winston, New York. THOMAS, S., AND CORDEN, M. (1977). Metric Tables of Composition ofAustralian food. Australian Gov-

ernment Publishing Service, Canberra, Australia. WILLS, R. B. H., MAPLES, J., AND GREENF~ELD, H. (198 1). Composition of Australian foods. 7. Minerals

in Lebanese, Chinese and fried take-away foods. Food Technol. Aust. 33,274-6. WOODROOF, J. G. (1983). Peanuts: Production, Processing, Products. AV Publ. Co., Westport.