sociolinguistics bakhtin

-

Upload

stephanie-abraham -

Category

Documents

-

view

254 -

download

2

Transcript of sociolinguistics bakhtin

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

1/27

A sociolinguistic application of Bakhtins

authoritative and internally persuasivediscourse1

Lukas D. Tsitsipis

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

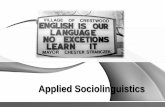

Through the use of two central Bakhtinian concepts, authoritative and intern-

ally persuasive discourse (word), this paper examines the tension between the

ideology of linguistic hegemony as a source of power in the Greek public

sphere and the condition of language shift faced by the Albanian-speaking

communities of modern Greece. I argue here that a cautious application of

these two notions, which are relevant to linguistic ideology, can reveal crucial

aspects of two processes: that of subordination to and that of questioning of

the dominant linguistic ideology by local Albanian-speaking communities.

Thus, in language shift contexts, it is possible that no simple relations obtain

that place social agents in unquestionable and easily predictable positions.

Such an approach proves useful for the sociolinguistic study of threatened

language communities.

KEYWORDS: Language ideology, Bakhtin, authoritative and inter-

nally persuasive discourse, language shift, Albanian, Greek

INTRODUCTION

This paper examines linguistic ideology as a signicant mediator in languageshift. The newly coalescing eld of linguistic ideology provides us with tools to

avoid mechanistic assessments of dynamic linguistic phenomena (Schieelin,

Woolard and Kroskrity 1998). Following this lead we can critically rethink some

of the teachings of traditional, positivistic sociolinguistics of the 1970s. My

empirical focus is on some ideological issues concerning a minority speech form

of Albanian, known locallyas Arvan|tika, which is spoken in modern Greece and

which, on the basis of sociolinguistic criteria, can be viewed as a threatened lan-

guage (for a recent account of the shift, seeTsitsipis1998, and discussion below).

I will elaborate here on language ideology using some concepts derivedfrom Bakhtin.With my analysis focused on particular communities, I want to

di th ti l i th t l t B khti t th t d f li i ti

Journal of Sociolinguistics 8/4, 2004: 569^594

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

2/27

been applied rather casually.2 It is therefore useful to operationalize some of

Bakhtins concepts in an accurate manner following the lead, for instance, of

Hills and others analytical attempts in various writings ^ not all of them

presented and discussed here.3

Local Arvan|tika communities, which provide the empirical data for this

essay, are agents in complex networks of relations with wider formations such

as the nation-state in the context of which linguistic shift is gradually taking

place. The Greek state and the bilingual Greek-Albanian communities are

mutually interlocked in praxis and ideology. The communities do not simply

exist within the connes of the nation-state and carry on along lines parallel

to those of the matrix society. They relate to these superimposed structures

through various socio-economic, administrative, and communicative net-

works which allow local ideologies to address ocial linguistic views. Someof the background of the shift will be presented in order for sociolinguistic

analysis to derive its power from social theory and history.

BAKHTIN ON DISCOURSE

Since Bakhtins work is not a novelty in sociolinguistics and linguistic anthro-

pology I choose here to focus on two of his concepts, authoritative and intern-

ally persuasive discourse, which have not had much currency in sociolinguistic

works, even though ideas of authority, power, and their relations to ideology

are common in many trends of critical discourse analysis and sociolinguistics

more generally.

Some of the portable notions of Bakhtins theoretical framework such as

voice, word, and dialogism, in their most explicit form, are found in his work on

Dostoevskys poetics (Bakhtin 1984). Bakhtin there, in addition to a thorough

analysis, also oers the concepts, more specically those of the voice and of the

word, in table form that facilitates their application in other contexts (1984:

199). The wordof language, sometimes referred to as discourse, recognises not

only its referential object, but also the word of the other, a word invading, so to

speak, the speakers world from the outside and carrying over its social accents

and background to another consciousness. Thus a word often becomes double-

voiced, and its voices constitute ideological positions on the world. Dialogic

relations therefore exist even in a speakers formal and syntactic monologue,

and a proposition is never complete until it becomes an utterance by being

socially anchored and responsive to other voices (Bakhtin 1986).

AUTHORITATIVE DISCOURSE, INTERNALLY PERSUASIVE DISCOURSE,AND POWER

570 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

3/27

our own . . .; it is, so to speak, the word of the fathers. Its authority was already

acknowledged in the past (emphasis in the original). And elsewhere, Others

words become anonymous and are assimilated (in reworked form, of course);

consciousness is monologized. Primary dialogic relations to others words are alsoobliterated . . . (Bakhtin 1986: 163) (emphasis in the original). Bakhtin contrasts

this to internally persuasive discourse. Internally persuasive discourse forms an

opposite pole where authority does not reign unquestioned. It is not insulated

from the world of other voices. As against authoritative discourse which is

understood as coming from the past, from the ancestors, internally persuasive

discourse is open to engagements in dialogic relations with other points of view.

It resists other voices and is being resisted and simultaneously penetrated by

them. As Bakhtin puts it,a conversation with an internally persuasive word that

one has begun to resist may continue but it takes on another character: it isquestioned, it is put in a new situation in order to expose its weak sides . . . (1981:

348). In my discussion of the Arvan|tika data below I will try to show why we

need both kinds of discourse for the studyof linguistic ideology.

It is useful to try to bring home these two concepts. Authoritative discourse

obviously presupposes two entities, a sending source and a receiving desti-

nation. In theory at least, and in order to operationalize this and subsequent

concepts for the requirements of empirical analysis, it is legitimate to make the

hypothesis that an authoritative word may stem either from individual or

collective agencies. Other, analogous analytical categories which take intoaccount individual or collective entities have been used in sociological and

sociolinguistic studies such as Gomans (1990) personal and tribal ^ meaning

here, group ^ stigma. But the following limitation should be kept in mind.

These communicating sources are not also two dierent voices, as, for instance,

when two opposed views are expressed and struggle with each other, lest we

want to undermine the very nature of this kind of discourse. Furthermore,

authoritative discourse is not limited to certain categories of texts or discursive

genres, but also includes the power of textual performances (Kuipers 1990: 7).

An important feature of authoritative discourse is its totalizing nature.Whether it is rejected or accepted, it is viewed as an unfragmented whole. This

makes this discourse inherently ideological. What makes authoritative word

an appropriate notion for analysis here is that it holds a deep anity with

linguistic ideologies: social agentscommonsense understandings of language

structure and praxis. As Kuipers (1998) has cogently argued in his analysis of

the fate of ritual speech on the island of Sumba, Indonesia, languages are

accepted as such only if they are perceived as totalities. This is an attitude

shared equally by some linguists and also na ve observers. Everything less

than a total linguistic structure, for example, shifting languages, threatenedlocal varieties, pidgins etc., is taken to be something not worthy of the label

f h l F i i t f i hi h t f

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 571

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

4/27

sympathy: that is, a positive, but a frequently condescending, attitude which

does not save formerly ourishing linguistic structures from becoming prey to

an expanding linguistic predator. Authoritative discourse operates by erasure.

Erasure as an ideological mechanism simplies the eld of observation bymaking sociolinguistic phenomena, languages, and social entities invisible

(Gal and Irvine 1995). This kind of discourse, whether accepted or rejected,

produces non-reexive thinking, and thus constitutes a component in the pro-

cess of misrecognition: the combination of subjective blindness and objective

legitimation (see Bourdieu [particularly translators denition] 1984: 566).

However, importantly, authoritative discourse is not to be automatically read

as a discourse of power even though it contains the potential of power. Power

is not simply dialogic or monologic. It requires an external, a social dimension

coloring, so to speak, discourse with the relational properties of the agentsinvolved (see Bakhtin and Medvedev 1985: 133 on the external, sociolinguistic

dimension of the genre). Caton (1990) discusses the role of this dimension for

the study of the praxis aspects of poetry. These relational properties will be

focused upon in the analysis of the examples. For an authoritative word to

become the word of political power, a eld is presupposed in which social

agents meet on unequal terms. For the tense relationship between Arvan|tika

and Greek, for example, and, more specically, for the hegemony of the Greek

language to take hold of the local communities, something like a public sphere

is required. This allows for the embedding of the Bakhtinian concept in apolitical and sociolinguistic context.

The Greek public sphere has assisted ocial language discourse to become

powerfully authoritative, but as I will argue here, not without being questioned

by internally persuasive discourse. I should add that I use the Habermasian

notion of the public sphere loosely (Habermas 1989). This is a problematic con-

cept, particularly with regard to what it excludes and what it includes. Never-

theless, it remains useful if cautiously applied. Cmiel (1990: 130), for example,

notes that public oratorical discourse and language decorum in nineteenth-

centuryAmerica were guarded by women, but to be used only by men. I adopthere Gals (1995: 418) denition of the public sphere as a kind of legitimation of

political power. The reason for using the analytical concept of the public

sphere is that bureaucracies and formal institutions do not suce to explain

the spread of the ideology of the ocial, standard linguistic norm and the

guarding of its authority. In order for such an ideology to be inculcated in

speakers social consciousness, more diuse vehicles are also required such as

a public discourse, media, popular conferences, daily conversational routines,

and the role of amateur or even professional students of the communities.

Such channels help shape, among the members of local speech communities,a certain sense of linguistic self or identity formed in a constant dialectic with

th t d di t d h i d l f th G k l M t k

572 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

5/27

metaphor but as a set of theoretical and methodological tools shedding

important light on particular sociolinguistic data.

THE ALBANIAN-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: ANALYSIS OF THE DATA

The national imagining of the Greek nation-state in the19th century (Anderson

1991) has led to a mechanism that I call subordination following Laclau and

Moue (1985). This mechanism is responsible for the subjection of a social agent

to the decisions of another when no signicant discourses of resistance surface

to question the dominant power (for a discussion focused on this process and

for linguistic ideology in relation to it, see Tsitsipis 1995). We should also take

note of the fact that Andersons work cited above does not adequately account

for the linguistic aspects of the problem but I do not wish to discuss this issuehere. The gradual emergence of the state and later techno-economic develop-

ments have solidied the ocial discourse of the monoglot standard (Silverstein

1996) which forms the basis for the construal of everything else as deviant.

The Albanian-speaking communities, domiciled in what is now Greece for

about ve centuries following the demographic and social transformations

of the late Byzantine era, have come to adopt the hegemonic pattern that

Hamp (1978) calls self-deprecation. The Albanian variety spoken in Greece,

Arvan|tika, represents a conservative branch of the southern major dialect

division of the Albanian language,Tosk (the northern dialect being known asGeg). Members of the Arvan|tika communities in Greece are bilingual in

Arvan|tika and modern Greek, whereas their sociolinguistic proles include

uent and terminal speakers. As a sociolinguistic category, terminal speakers

are bilingual members of the communities with a severely diminished gram-

matical and lexical competence in the minority language. Abundant evidence

suggests that the Arvan| tika language is undergoing shift (Sasse1990;Tsitsipis

1981; for the state of the art with regard to language shift studies, see Dorian

1999; for language shift, language rights, and various rhetorics for their inter-

pretation, see Errington 2003). Even though the age ranges in which terminaland uent speakers of Arvan|tika can be allocated vary from community to

community, the sociolinguistic distinction concerning speaker-competence

levels in the language is more or less stable across communities (for dierences

and similarities between the Arvan| tika case and that of East Sutherland

Gaelic, see Dorian 1981, and various references to Tsitsipis in this article).

Long-term ethnographic and sociolinguistic eldwork has been carried out in

several Arvan|tika speech communities in south-central mainland Greece.

Data for this study are derived from the two communities of my main research

focus, the southern semi-urban locality of Spata, and the northern, mountai-nous village of Kiriaki.

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 573

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

6/27

the need for what Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer (1998) call ideological

clarication concerning Amerindian languages of southern Alaska

should be viewed in a dierent light when applied to Arvan|tika. Since

people in the Alaskan communities exhibit a strong pro-minority rhetoric butdo almost nothing to bring it about, these scholars take ideological

clarication as a prerequisite to a successful reversing of linguistic shift. This

praxis-cum-attitude complex, resembling what I call performative contradic-

tion, that is, the making of statements that are pragmatically undermined, so

that constative and performative dimensions are in opposition, does not have

many chances to succeed in the Balkan case under examination. Due largely

to the hegemonic eects of the authoritative discourse, no serious eorts

have ever been made to reverse the shift. It is better to view ideological clari-

cation as a sociolinguistic universal taking on dierent contents in dierentcommunities.

In the Arvan|tika enclaves a kind of authoritative discourse shows up

which, as Bakhtin notes, comes from the ancestors, the details of its specic

character being locally determined. The national imagining, requiring

legitimation which stems from some remote and non-negotiable source, is a

good candidate for this kind of discourse. Arvan|tika speakers construe

their identity through identication with the fate of Greek history. It has

become their own. An Arvan| tika philologist of the 1960s oers the following

commentary:

Extract1

In the Arvan|tika villages, at least in those ones which had the privilege of

transportation, recent decades have been characterized by the evolution of civil-

ization, the decrease in the usage of Arvan|tika and the advancement of Greek.

Today, it is only in some isolated villages that one can hear Arvan|tika mixed with dis-

torted Greek spoken by old people . . . However, in areas where ease of transportation

has brought about an intensive contact of old Arvan|tika villages with the city,

the life of these peasants has nothing to remind us of their earlier characteristic

peculiarities. (My translation from Greek; Biris 1960: 329)

This work has a title that refers to Arvan| tika people as the Dorians of Modern

Hellenism. It lters Arvan|tika society ethnohistorically through the geneal-

ogy of the Greek nation. Birisand others views belong to a tradition of nation-

alist discourse which includes also an emphasis on progress, iconically related

to the ocial language, Greek. A crucial component of this ideology is a

linguistic corrective that demands of all marginal or deviantdialects, varieties,

pronunciations, etc. that they conform to the canon of purity. This view marks

a, still active, pre-linguistic phase in Greek intellectual life that diers fromwestern sociolinguistic studies. National imaginings, to be eective, have to be

t t li i I di id l d i l t ll d t b l ti

574 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

7/27

supported by the power of the historically legitimated public sphere, operates

by erasure: that is, no other alternatives are considered.

At a popular conference on Arvan|tika with the participation of historians,

anthropologists, folklorists, activists, local politicians, and other concernedpeople (on popular conferencing, see Tsitsipis 2000), the issue of the authority

of a unied and unfragmented language allowing no interference from other

centrifugal forces (voices) was put into relief by various participants. The

following extract comes from an amateur linguist of Arvan| tika origin, who,

in his several interventions in favor of Arvan| tika, falls prey to the discourse of

the monolingual authority:

Extract 2

G.M.: An answer concerning the written status of the language [Arvan|tika] followsthe answer as to whether the language is unied. And the answer is that the

language is one, unied, unfragmented. Entities such as Arvan|tika, Albanian,

Arbe resh [a label applied to the Albanian-speaking communities of southern

Italy] and others do not exist. By the same token, there are no people of

dierent kinds who use this language. That is, there are no Arvanites people,

Albanians, etc. The people is one. (My translation from Greek; for conference

proceedings, see Empirikos, Ioannidou, Karatzola, Baltsiotis, Beis, Tsitselikis

and Christopoulos (eds.) 2001: 341)

Even though the speaker focuses his discussion on Arvan|tika, he does not alsotreat it in the context of a logic dierent from that of nationalist language ideol-

ogy. The value and prosperity of the language is here understood through the

symbolic domination of the Greek monoglot standard, but with Arvan|tika as

the explicit referent. Generations of people having undergone Greek education

are aware of the totalizing nature of linguistic oneness. This ocial discourse

is simply transferred down and applied to the local linguistic forms. Even

though such ideology of oneness appears to treat all members of the various

ethnic communities, and citizenry in general, on equal terms, it crucially

undermines the voices of minority groups and blocks their potential for recog-nition (Taylor 1997).

Extract 1, above, stems from a published source; Extract 2 comes from an

actual event in which the ethnographer was a participant, but I would call this

a remote participation since it did not meet the requirements for what we gener-

ally understand as a typical eldwork situation. The author was one among

many other co-participants even though his reputation as a specialist was

already known and established through previously published articles and

personal networks. In an early work, Hill (1970) argues that the researcher is

considered by the members of local speech communities as an authority inmatters concerning language and culture. This attitude, even though not

il i l i d f th it ti di

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 575

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

8/27

During the event from which Extract 2 is taken, many participants viewed

the various specialists as those who really know regardless of specic argu-

ments raised in the discussions. But published texts and large events reinforce

a tendency that Briggs (1986) has already discovered and discussed for themicro-level interview: they make the isolation of referential content from its

indexical surrounding much easier by severing the ties between what is said

and actual interactions. Thus, issues such as who speaks to whom, and in

which conditions (Hymes 1974), are either erased or are carried over to the

communicative situation already ideologically constructed prior to the event

(specialists versus amateurs and natives).

For the oral texts and interactions which follow, some observations on my

role as an ethnographer are in line since this introduces the necessary reex-

ivity that is exactly what is missing from traditional interviews (seeBriggs 1986). As against the pure image of the specialist as briey described

above, which is quite abstract and is one of the many guises that authority

can take, even unwittingly, on the part of the researcher, in the immediate,

face-to-face interactions, conditions are more complex. Philips (1993: xi

^xix) in the new introduction to her work discusses the signicance of

microethnography using tools from interactional sociolinguistics, discourse,

and conversation analysis vis-a' -vis traditional ethnography. Furthermore, it

must be added here that, since part of the focus of the larger sociolinguistic

project on language shift was the study of ideologies, frequently an elusivesubject, a long contact had to be established between the consultants and

myself before an investigation of linguistic ideological views could be

embarked upon. Narrative texts and interactions analysed in this work have

been collected basically from older and middle-aged speakers who retain a

maximum of narrative competence using resources from both languages

(see Tsitsipis 1988 for a detailed treatment of this issue, and discussion below

for data collection). Several of the extracts cited and discussed here are non-

continuous selections from the original transcripts. I have made my choice

of the particular chunks though in such a manner as not to distort inter-pretation. That is, the inclusion of additional material would not profoundly

aect the analysis. I have marked the point of the break between what is

omitted and what is included only for Extract 5 since conversation

with these consultants including the specic extract was on and o for

several sessions over a span of a few days (for transcription conventions see

Appendix).

Extract 3 is a conversational interview between myself and two women.

One, Ms Gar., was ninety-seven years old, back in the early 1980s, and the

other, Ms Argh., was middle-aged, the daughter-in-law of the rst, fromKiriaki village, in central mainland Greece. This extract is doubly

bi d f ti ll t b i t i t t d (B i

576 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

9/27

Extract 3

Ethnographer: 1. rr|mte che ka te tho te ?

rr|mte what does it mean?

Ms Argh.: 2. to len i Zerikje ses pu le me to lazhu ri i mblju am

Zer| ki (a village name) women say this as we say the

lazhu ri i mblju am (blue)

Ms Gar.: 3. i mblju ami e tho mi atje lazhu rit [shkru aj de]

lazhu rit is the name for blue [write down cmon]

4. lazhu rit ja tho mi i mblju am pe r fuste ne

lazhu rit is the name ofthe blue of (womens) skirts

Ms Argh.: 5. [p|ej tidhe te thot jaja ja][drink (your coee) while grandma is talking to you]

Ms Gar.: 6. ie kji nu sxja fuste ne nji soro ie kji, ie kji, ie kji

the daughter-in-law has a lot of dresses (she) has, has, has

Ethnographer: 7. si tho ne to siko ti to plemo ni ?

how do theycall the liver the lung?

Ms Gar.: 8. Mulsh|e zez mulsh|ebardh

liver lung

9. bu rri ka nji mulsh|te bardh e nji te zez

man (human being) has a lung anda liver

10. kadhe pache

has also bowels (intestines)

11. edhe ne ve ke mi pache

and we have bowels

12. te r, te r i ke mi ata ne ve

we have all, all those (things)

13. nan| che te tho mi ? [pxje kafe ]

now what should we say? [drink coee]

14. u kam enen| nda epta v|tra

I am ninety-seven years old

15. prohore s pe r te shkonj

I am now about to die

16. [ura te n te kesh]

[be blessed]

In this interview what Briggs (1986) calls communicative hegemony is

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 577

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

10/27

unusual ^ from their point of view ^ genre of communication. But Extract 3,

even though a pragmatic reection of an outside authoritative discourse, is a

multilayered event (without turning itself into an instance of internally

persuasive discourse on which there is more, later in this article). Atvarious places participants break out of the question^answer frame to refer

to everyday life conditions either by providing realistic frames for the terms

investigated (lines 6, 9, 10, 11, 12), or by expressing directive-aectionate

speech acts (lines 5, 13), or by oering autobiographical information (lines

14, 15) accompanied by formulas marking age-related communicative rou-

tines (older people express wishes for a long life to younger people, line 16).

A social self is thus projected which suggests more than just a passive accept-

ance of an outsiders authority. It is the turning of an interview situation

into a somewhat unmarked public interaction. Voices such as the onesdepicted in Extract 3 are quite representative of local, village or semi-urban-

sized, communities (for statistics dierentiating community types, and for

critical remarks on such statistics with reference to nationalist ideology, see

Tsitsipis 1998: 16^18).

On the basis of an examination of a large corpus of conversational, narrative,

and interview data we can discern a continuum from a more private (or semi-

private) to a more public discourse. Since my research in both communities

focused on both linguistic and sociolinguistic phenomena, the data collected

consisted of long hours of conversations, quite frequently the oering ofunprompted stories, and questionnaires, including translation tasks testing

for linguistic competence in both languages and searching for social and bio-

graphical information. Thus an exchange, which started as a formal interview,

could often end up as a relaxed conversation with a variety of embedded topics

covering a range from personal accounts to discussions of wider social issues.

From the above, it becomes clear that the corpus just mentioned derives from

mixed eldwork conditions that moved from the most formal procedures to the

least formal ones. In collecting the corpus and judging which procedure

would be the most appropriate, I had some advance knowledge as to whowould be the best and most forthcoming narrators. This was not designed to

exclude the competent narrators from the formal testing of their bilingual

competence but to prot most from their spontaneously emerging narrative

skills. Investigation of interactional routines across contexts suggests that

communicative choices such as the ones in Extract 3 are quite typical across

situations, with parameters such as age, sex, etc. being responsible for vari-

ation in style. However, as a comparison of Extracts 4 and 5 will show, not all

speakers are equally inclined to produce an authoritative voice stemming from

the world of tradition (see analysis below). Two important processes remaintherefore to be discussed: the rst is a second type of authoritative word

h t i ti f th id l i l t t f th A tik iti

578 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

11/27

Before contact through schooling and centralization of state bureaucracy

intensied, and, consequently, legitimation of the Greek standard spread to

the periphery, it was Arvan|tika language that was perceived as the word of

the ancestors. Around the 1950s and earlier, the impact of administrativesystems linking local communities with the central bureaucratic structures

was not so strongly felt. I have called the condition that prevailed locally,

and still does to some extent, indexical totality: a full correspondence between

a linguistic and a non-linguistic order in speakers commonsense under-

standings. This in turn erases from view any possible dierences among

local linguistic varieties and groups. It is this totalizing discourse that the

Greek standard turns into fragments (viewed as mixed) and substitutes in its

place its own authority (on fragmentation, see Tsitsipis 2003). Since two

separate totalizing ideologies succeed one another in the history of thelocal communities, but not as a smooth replacement process, I argue that

authoritative discourse is not intrinsically endowed with power (only histor-

ically does this happen). This emerges naturally out of the dierent power

potential that the Greek standard and Arvan| tika traditionalist linguistic

views exhibit.

Here is an extract from a conversation with an elderly speaker, with the

initials D.P., an octogenarian woman from the modernized community of

Spata in southern mainland Greece, referring to this earlier condition:

Extract 4

D.P.: 1. ne ve kakoshku ame , ne ve ata v| te ra

those years we faced hardships

2. r(r)e mo nje me , kladhe pse me vre shtate

(we) dug (the soil), cut the branches of the vines

3. puno nje m me sust me ka re ne ve im

we cultivated (the land) we moved with a carriage

4. ne k ke im kje [ . . .] kakoshko jne ko zmoswe didnt have oxen [ . . .] people had a hard time

5. ne ala dho ksa to theo o mos

yes but anyway God is blessed

6. shko nje m me mir, she ndo shat m|ra

we had a better time, in good health

7. dhe she rbe nje m ala ha im

and we worked but we (had) to eat

8. ta te ne ke ime njikokj|r shum

we had a hard-working father

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 579

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

12/27

10. edhe ta ta na it Elinika

and the father also spoke Greek to us

11. neke | shne shum paleo

they were not that old-fashioned

12. Arvan| te, Arvan| te, kuvendo in Arvan| te

Arvan| tika, Arvan| tika, they spoke Arvan| tika

13. Arvan| te ata plje kjte

these old people (spoke) Arvan| tika

14. El inika kuvendja zame ta pedhja

the children spoke Greek

15. dhen guvendja zame Arvan| tikawe didnt speak in Arvan| tika

16. me tis ghrie s maz| le me tArvan| tika

with the old women we speak Arvan| tika

17. pjo e f kolo to ra a ma vro tis sinomil| s mu

it is easier now if I run across my age-mates

18. me tis Arvan|tises Arvan|tika

with Arvan| tika women Arvan| tika

19. oh, oh, panij| r, ske a rdhure ke tu ne panjij| r

oh, oh, (quite) a feast, you havent participated in the feast

20. Arvan| te che ke che nje m horo ke ndo nje me

we were dancing (in) the Arvan|tika (tune) (quite) a dance and we were

singing

21. ve je me nde klj|se , v|nje me nga klj| sa

we went to the church, we came back from the church

22. to ra dhen hore vume dhen ga numenow we dont dance we dont do (things)

23. ha las e o ko zmo s to ra, u-hala s panjij|ri nan|

the world has deteriorated now, the feast has deteriorated now

24. ske mi panij| r, neke | shte ko zmi a| paleo che ish

we dont have the feast, there are no people like the old ones that used to be

25. ne ve je mi bastardhu e misho kje misho

we are bastardized half and half

26. le me ta Rome ika le me kje tArvan| tika

we speak in Greek and we (also) speak in Arvan| tika

580 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

13/27

I will not focus here on the intricacies of the narrators code-switching. This

extract is characterized by what Hill (1998) calls a nostalgic ideology.

Arvan| tika is projected not simply as part of an earlier state of aairs, that is,

as a synecdoche, but as the totality of this past. It is both indexable by andindexical of the social order. This is what I call indexical totality, which allows

a traditionalist authoritative discourse to surface. This past order is viewed

through erasure, and, hence, through misrecognition, as admitting of no

fractures or interference from other voices.

True, since the shift was already underway in earlier times, the narrator

makes a concession by admitting that her parents used Greek to address young-

sters (lines 9, 10) and that children were speaking Greek among themselves

(line 14). But everything else was understood as intrinsically related to Arvan| -

tika. Agricultural activities, physical suering and endurance, good health, andadequate or inadequate subsistence along with respect for social order appear

as a module ( lines 1 8), and are construed as indexed by the use of Arvan| tika

which also marks local festivities and religious conduct as emblems of an earlier

order (lines18 21). This is sharply contrasted to more recent times when the lan-

guage is no longer a totality (through hybridization and syncretism with Greek)

and the social order has morally deteriorated (lines 22^26).

A question related to that raised in connection with Extract 3 above, that is,

how typical or representative of local voices Extract 4 is, is relevant here too.

We can answer this by providing a richer contextualization for the example.The narrators projected social self recapitulates and foregrounds the author-

itative word of the community as its legitimate representative. This authority

is not locally invested in just anybody, but crucially in those individuals

whose age and social background make them good and reliable spokes-

persons for the communities wisdom and collective ideology.5 What is

meant by social background is a constellation of features including bio-

graphical characteristics of the speakers as well as historical conditions

shaping these characteristics which allow them to produce the word of tradi-

tional authority. The narrator of Extract 4 has undergone and felt the majorstages of the, still ongoing, linguistic shift, and oers here an expository,

historical account of the social and linguistic changes. She combines

this exposition with her ideological, evaluative reading of a social world

dominated by the authority of Arvan| tika. At line 19 she prexes her nostal-

gic discourse about the longed for (and now perceived as decreasing in

authenticity) local festivities with the use of the aectionate, exclamatory

particle oh dramatically reduplicated. This memory management by the

speaker foregrounds for her audience the word of tradition.

We turn now to another narrative case that is not so strongly ideological innature. Nevertheless, some of the nuclei, as I have called them, which express

k b i t d id h h t Th f i f li i ti

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 581

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

14/27

crucially depends on a combination of factors such as social background, his-

tory, and participant structures, as already suggested above. Incidentally a

view that takes account of all these factors corroborates a position expressed

by critics that not all discourse should be considered as ideological. Eagleton(1991), for example, in a critique, argues that Foucault, through the concept of

discours, trivializes the notion of ideology since, if it explains everything, it

explains nothing. The following extract is from a conversational narrative by

the same participants as in Extract 3 above:

Extract 5

.......................................................................................................

Ms Gar.: 1. kam djelm ke ta e me zhdo nje n me mir na me m

I am surrounded by these children who take care of me better than(their own) mother

2. pred|a, ura tze n te Kr| shtit edhe She rmer|s te ken

my God, the blessing of Jesus and Holy Mother may they have

Ms Argh.: 3. jam ke tu , katuna re, u jam nu se e hu aj

I am here, a villager, I am a foreign daughter-in-law

Ms Gar.: 4. e kaloshko nj me dre nje n djeljm shum

and I have a good time children care for me a lot

5. nu kam parapon|, enen| nda epta ate nuk e kto nem

I dont complain, ninety-seven (years old) those (things) I dont

remember

6. te rro nje n dje ljme t u ke tu rronj

I wish a long life to the children, I live here

7. ne hor kam va tur jo nAth|n

Ive been to the city not to Athens

8. mos me ne m dhen mboro na z| sowishing me a long life is a curse I am not able to live

9. jat| ta podha rja mu tsak| san to fos mu p| re

since my legs are weak my sight gone

10. mos me ne m, ala du a te vdes che u-vare she s

dont curse me, I want to die since I am bored

11. dhen to the lo to zo| mu egho ?

dont I want my life ?

12. me vwa me vdikj, kam kakoshku ar

my brother died, Ive had a hard time

582 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

15/27

14. edhe kjo glju ha e mir (lowering her voice)

and this language (Arvan|tika) (is) good

15. kakoshko va u-martu ash mo ra kte burr

I had a hard time I got married I took this man

16. nuk bera fam| lje me ke te burr

I didnt make a family with this man

17. nu ku k| she m t ha im

we didnt have enough food supplies

18. si mos i kto nem!

I do not remember these (old) things!

19. [je chahpen dhe mos jesh][you are quite smart for a person who is not (Arvanitis)]

20. na z| sis hro nja pola san kje me na

may you live a long lif e like me

Turns at talk by the speakers of Extract 5 are extracted from a much

longer text, which exhibits a high degree of repetitiveness. It must be

mentioned that Extracts 4 and 5 are speech tokens with minimum prompting

by the ethnographer. In Extract 5, for instance, we notice loose cohesive

ties among the various statements by Ms Gar. (line 5, for example, in whichstatements are not hypotactically connected and have unrelated referents).

This is only partly due to my own selection of fragments from the longer

discourse. Self-repair is conspicuously absent from these and the majority of

Arvan|tika narratives and conversations, and in those rare cases in which it

shows up, self-repair seems to be limited to extremely factual information.

One could tentatively claim here that this serves as an index of the lack of

formal speech contexts.

Comparing Extracts 5 and 4 above we notice the following: audiences and

speech event structures are almost identical in the two cases. Dierencesshow up with regard to speakersgoals and their social biographies. E xtract 5

is an autobiographical narrative by a very old, but not senile, speaker. But so is

Extract 4 to a great extent. In Extract 5, in lines 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, the speaker

makes the usual statements expected (at least to a large extent) in elderly dis-

course concerning her life with children, blessings and wishes to children

(see also Extract 3 above) and disclaimers of memory, an almost stereotypical

performance feature. At line 7, the speaker identies an unnamed urban center

and adds the caveat that this is not Athens: hor*hora (a Greek loanword) refers

to any town or city that functions as an administrative point of reference.Athens (the capital city) is still outside the horizon of the speakers everyday

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 583

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

16/27

in Extract 4, and so do the lines of the rest of her narrative, accompanied by

various wishes.

Line 14 mentions Arvan| tika language but in a lower voice. Both the intona-

tion and the context of the speakers other statements suggest that thelanguage issue is not topicalized here. No heightened awareness of an indexi-

cal relation between a language and social order is foregrounded in Extract 5

as against Extract 4. The word that takes Arvan| tika to be linked to an unfrag-

mented traditional order is severely weakened in Extract 5. The narrative por-

tion cited here as Extract 5 is a shadow of an authoritative discourse. Since

language issues are only an aside vis-a' -vis the main focus of the narrative, no

authoritative pronouncements are to be read in the narrators views. This

speaker, very little touched by the linguistic shift, is not functioning as a propo-

nent of a certain kind of ideology. Politically speaking, she is not an interestedagent. On the basis of the preceding analysis I call this narrative extract a

shadow of authoritative discourse since only a slight trace of the Arvan| tika

language authority can be detected in the speakers narration. Looking again

at lines 14 and 15, we notice that these two lines stand out of the rest of the text

as the only ones that relate language to earlier conditions of life at the societal

level. Thus, the presence of the ideological nuclei, matching language with an

extralinguistic reality in speakers views, is very tiny in comparison with

Extract 4.

The lines of the elderly speaker of Extract 5 are full of confessional detailscombined with formulaic expressions (such as line 17 mentioning poverty)

which show up again and again in Arvan|tika narratives of uent speakers,

diering slightly among themselves in their wording (for a discussion of

the subject of formulaic expressions, see Tsitsipis 1989). The confessional

structure of the major part of the narrative argues for a spontaneous

discourse of a kind that makes the possibility that the speaker is framing her

words as a make-believe strategy seem very remote. At the time of the interview

this woman was already a non-active member of the communitys life, and

thus least endowed with the power to represent the authority of tradition.What the speaker does is to make a portion of her private life available to the

public gaze.

The examples above suggest that the authority of the Greek standard is

progressively replacing the authoritative discourse of tradition. The latter

perceives the earlier condition as dominated by an almost monolingual

Arvan| tika cultural world. An interesting variation shows up: not all speakers

are equally inclined to produce this ideology even though they may accept it

passively most of the time. This is a kind of subtle variation not easily suscepti-

ble to statistical analysis. In addition to the conclusions reached on the basisof this variation in the particular empirical case, what speakers say about

th i li i ti ti th di l ti b t di d t di

584 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

17/27

BETWEEN THE TWO WORDS OFAUTHORITY

Since we have two historically attested authoritative discourses which derive

their respective power from the ways social agents are related through external

social forces, where does internally persuasive discourse come from and how

does it surface? The meaning of the internally persuasive word is not as trans-

parent as that of the authoritative word. Whether the object of this word is

nally accepted or not, it nevertheless becomes the locus of contestation. The

best way to operationalize it, therefore, is to view it as an ideology that upholds

something and questions it at the same time, that is, as a struggle of voices.6

The hegemony of the Greek state apparatuses does not leave much room for

strongly felt anti-hegemonic discourses. One reason for this is that the social

and economic structures of modernization have forced the material conditions

of the local communities to radically change, not least, the potential for their

reproduction in anything like their previous state. This is better grasped if we

also take into account the powerful forces of reexivity of late modernity as

analyzed by Giddens (1991). The massive production and circulation of descrip-

tive and ideological discourses through electronic and other media reaches

local communities, which in turn react and adjust accordingly. A similar situ-

ation is described by Eagleton (1976: 55^56) for the genesis of English as a

national language, as well as for its dominance in Ireland. However, it must be

added here that the phenomenon of social reproduction of the powerful variety

(Bourdieu1991), is not universal (seeWoolard1985, for a discussion of this issue).

But this historical situation should not blind us to the fact that we are

not dealing with a smooth succession of one authoritative discourse, the

traditionalist, by another, the state hegemonic. Even though Greek symbolic

domination seems unquestionable, since this condition is being constantly

reinforced by the operation of schooling and bureaucracy, elements of hetero-

glossia, that is, the viewing of one language through the eyes of the other

(Bakhtin1981), show up in the ideological-linguistic statements of the commu-

nity members. At the local level, the symbolic dominance of Greek is fragile

and fraught with contradictions. Speakers, in their naturally produced narra-

tives, simultaneously accept and reject the role of the Greek language. Else-

where I have called this (Tsitsipis 1998: 119^132) contradictory discourse. A

kind of ideology that shifts from praising Arvan|tika to viewing it in negative

terms coexists with congruent linguistic ideology that faithfully reproduces

the dominant discourse. It is this kind of linguistic ideology that I call intern-

ally persuasive discourse. This discourse captures the whole situation as a

process and not just as a static condition, as is frequently the case with contra-

dictory discourse. In simple contradictions something is an A and its existen-

tial negation at the same time. In persuasiveness, one starts somewhere in

order to reach a dierent point.

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 585

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

18/27

conversational contexts they question the authority of Greek, but without restor-

ing Arvan|tika to a pure and ideologically uncontaminated state. Such discursive

moments argue in favor of a thin hegemony of the national standard (Scott 1990),

if not as a constant feature of the relations between the two languages and theirrespective speakers, at least, as a transitory one. And we have well-attested ethno-

graphic cases in which linguistic contestation prevails (Gal1993).

Greek authoritative discourse, operating by erasure, claims for itself a kind of

loyalty that resists any questioning or undermining by external sources. Internally

persuasive discourse, therefore, by putting this authority under a light of

doubt, questions its totalizing nature. Here is an extract in which an internally

persuasive discourse in the form of contradictory ideology surfaces in the

speakers pronouncements.The speaker, G., an elderly man from Kiriaki, is actively

and reexively responding to the conditions and consequences of the shift:

Extract 6

G.: 1. em|s spe dhe a ta theoru me afu jen|thikam sti mitrikj| ghlo sa

we consider it (Arvan|tika) important since weve been born with this as a

native tongue

2. troma ksam na ma thume ta Elinika

we had a hard time to learn Greek

3. sas pro|pa o ti pa o na mil| so me sas kje anakate vomeI told you before that when I try to speak with you I get confused

4. dhe mboro na mil|so kathara

I cannot speak clearly

5. mu tohun pi kja li: es|dhen |se apto Kirjaki

others have also told me: you dont come from Kiriaki

6. a ma mil| so me nan dhikjigho ro, se nan pu |ne evrope os, i stin Ath|na

if I speak with an attorney, to somebody who is European, or in Athens

7. le i: es|s dhen mjazeste ja Arvan|tes

says: you dont look like Arvan|tes

8. ala i simberifora mu fe nete me pene vun

but my conduct seems to be such (that) they praise me

In this narrative portion, which is oered entirely in Greek by the speaker, a slid-

ing or contradictory type of explicit linguistic ideology shows up. The narrator

starts out at line 1 by praising Arvan|tika, but ends up with pronouncements

describing his diculties in dealing communicatively with a world in which theuse of Arvan|tika has become a negative symbolic capital: that is, interference

f th l l i t ith G k b d t i t l t hi i It i i th

586 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

19/27

the state, is both espoused and contradicted. No closure appears of the sort we

expect to nd in the authoritative word. As the narrator approaches the rst

clash of voices (lines 5 and 6), his speech is rendered momentarily dysuent.

The dysuency occurs exactly at the point where the speaker embarks upon hisrst quotation. The conjunctive connection also, and of line 5 with preceding

line 4 shatters the cohesive ties that one expects from the mutual logical adjust-

ment of the speakers turns. Something like but would be appropriate here.

However, in this context, the alien voice disrupts the local view of Arvan|tika.

The speakers reporting frame anticipates the view of his reported interlocutors.

This discursive context actualizes what Voloshinov (1973: 135) calls anticipated

and disseminated reported speech. The narrators quotation does not simply

reproduce the other voice. It struggles with it byanticipating it and byallowing it

to aect his own voice. A mutual infectiousness of voices occurs here. The factthat, in this and in other similar speech tokens, the idea of examining them in

the light of the internally persuasive word had not occurred to me, has deprived

analysis of potential tools helping sociolinguistics penetrate more deeply into

the problem of contradictions concerning linguistic ideologies.7 An analysis is

never complete unless all crucial aspects of the phenomenon, here the word of

authorityand the questioning of this authority, are taken into account.

CONCLUSIONMy discussion of linguistic ideology with the use of two central Bakhtinian

concepts, authoritative and internally persuasive discourse, oers a basis for a

more complex view of the eld of observation. There is no doubt that linguistic

ideologies have been central to early and classical work in sociolinguistics

under various labels such as attitudes, subjective responses, etc. Labovs

(1972: 314^317) indicators, markers, and stereotypes try to grasp such

stances towards linguistic forms entailing various degrees of conscious

awareness. Even the dialectic between evaluative attitudes and linguistic

change is given signicant emphasis in these early works (for a more recenttheoretical elaboration of the dialectic of structure, use, and ideology, see

Silverstein1985).

But traditional sociolinguistic work has primarily focused on isolated vari-

ables susceptible to statistical analysis. To the contrary, concepts such as those

derived from Bakhtin, take whole communities as their points of reference

along with their historical and sociological characteristics, as immersed in

power relations. One of the dierences between what we may call a positivistic

sociolinguistics and this approach lies in the fact that notions such as author-

ity, heteroglossia, persuasiveness, dialogue, etc. require simultaneously afocus on both correlational facts which are the social background, historical

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 587

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

20/27

Sociolinguists should not be faulted for not having discovered Bakhtin

before the appearance of his thought on the western academic scene. Neither

should they be criticized for not choosing to focus on his work. And how things

would have shaped in regard to sociolinguistic theory, particularly in the1960s, the formative years of the sociolinguistic paradigm, had Bakhtin been

better known, remains a question for counterfactual historians with linguistic

and sociological interests to study (for virtual history, see Ferguson 1998).

This is a task worth undertaking for its own sake but not appropriate for the

present article.

I mentioned above that a Bakhtinian perspective focuses on whole commu-

nities rather than on isolated variables. There is some support for this view

coming from other quarters of sociolinguistic and pragmatic theory. Mey

(1985: 341 349), proposing a distinction between traditional and criticalsociolinguistics (and here critical discourse analysis should also be included),

suggests that sociolinguistics, if it is to be a truly social science, must consider

peoples societal activities as a whole . . . (1985: 342). Mey criticiz es the isola-

tion of supercial variables assigned to rigidly separated political, social, eco-

nomic, cultural, religious, linguistic and other spheres. Here a distinction

between theory and method comes immediately to mind. Methodologically

speaking, the isolation of variables by researchers working in the mainstream

of the sociolinguistic tradition has produced admirable and emulable results.

But, in theory, building a focus on peoples societal activities as a whole hasescaped researchers interests or attention.

A similarly critical and sophisticated view is oered by Coupland (2001)

who, building on Giddens and Bakhtin, discusses the concept of the relational

self which anchors communication at the heart of agents interactions

rather than on variables abstracted from their deeper, in Meys sense,

class-determined, societal conditions. Coupland (2001: 197) further observes

that Bakhtins work is still text-focused which invites a readjustment of his

thinking to sociolinguistic realities outside the literary text. And this is

correct on observational grounds. But, I would add in the context of the presentanalysis, that by being textual Bakhtins work does not pre-empt later socio-

linguistic research by oering yet another variability-oriented analytical grid

with the well-known mechanical sortingoutof (frequently) supercial dimensions.

My approach in this paper has been, therefore, the reverse of ideological

erasure by which the eld of observation is simplied. Both analysts and local

community members frequently fall prey to such erasing abstractions and

generalizations. Traditional structuralist logic and logical positivism have

emphasiz ed the binary pattern of argumentation in which something is either

there or is not.Thus, hegemony is viewed as either prevailing in a certain socialeld or is not. The analysis above argues that, in addition to all-encompassing

d th it ti di t di ti h ki D h d

588 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

21/27

local ideologies according to what they themselves are prepared to see or

tolerate. As Kroskrity (1998: 115) notes, [L]inguistic ideology oers an ethno-

linguistic account that provides an insightful microcultural complement to

recent ethnographic and ethnohistorical eorts to rethink the socioculturalorder. . . In fact, Bakhtinian concepts make such a rethinking of inherited inter-

pretive orders and schemata possible.

NOTES

1. This paper stems from a presentation made at the Third International Crossroads in

Cultural Studies Conference, 21^25 June, 2000, which took place in Birmingham,

U.K., and particularly from a series of sessions on Bakhtins work. I would like to

thank the conference participants for some useful initial comments, and this jour-

nals editors Nikolas Coupland and Allan Bell. Both editors have oered substantial

help, support, and critical comments on earlier drafts of this piece in order to bring

it to publication. I am also grateful to my anthropologist colleague and friend from

the University of Thessaly, Greece, Penelope Papailias, who has given her time gener-

ously to correct style and provide signicant insights in regard to theory and con-

tent. The lecturer of our department Panagiotis Arvanitis has been very helpful in

setting part of the electronic format of this paper. Susan K. Shaw, the journals copy

editor, has been quite instrumental in giving the article its nal shape. Last but not

least the critical comments by two of the journals anonymous reviewers have con-tributed important guidelines for the improvement of the paper. I remain the only

one responsible for any shortcomings that have crept into the nal product.

2. Brandist (2000) is an example. But this scholar and other participants in the Bakhtin

sessions of theThird International Crossroads in Cultural Studies Conference derive

their basic argumentation from critical, l iterary theory, not sociolinguistics or

linguistic anthropology, and, as Urban (1991: 24) has cogently argued, linguistic

anthropology and literary theory are not expected to make an identical use of

certain concepts. A word of caution concerning the interdisciplinary application of

certain notions is always therefore a prerequisite for a serious analysis.

3. See Hill (1985, 1995). It should be noticed that Hills major concern has been with theoperationalization of voice. However, a fruitful line of investigation has been

broached in these works.

4. Some of the examples discussed in this paper have been analyzed in other works too

as suggested in references in the main text. The reason is that certain theoretical

and methodological views focusing on the examples cannot be adequately

exhausted in one article. New theoretical insights oer the possibility of further

interpretive depth to the texts.

5. This condition is interestingly similar to some of Benjamins ([1973] 1992: 107)

observations about the storyteller in his celebrated essay: [T]he storyteller joins

the ranks of the teachers and sages. He has counsel ^ not for a few situations, asthe proverb does, but for many, like the sage. For it is granted to him to reach

back to a whole lifetime (a life, incidentally, that comprises not only his own experi-

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 589

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

22/27

almost identical to the one presented in this paper: the traditional-ancestral

word of authority that has gone unquestioned for some time, till the dawn of a

new era comprising technologies, state apparatuses, a nd ocial languages trans-

mitted through mechanical means and the print industry.

6. History does not proceed byleaps, that is, from one pure state to the next. Such a posi-

tion could be adopted only by evolutionists with little or no regard for the historicity

of events (see Silverstein 1996: 302, for remarks on historicity in the social and bio-

logical sciences; also Holquist 1990: 25, on Bakhtins view of event which, in his

philosophical writings, is understood as being always in conjunction with the notion

of being, that is, being as an event). This simplistic view would provide little room for

heteroglossia (struggle of voices), since ideology is not always congruent but also

of a contradictory nature.

7. One of this papers anonymous reviewers has raised a thoughtful question concern-

ing the possibility of an alternative interpretation for Extract 6. Says this scholar:

. . . could it also be that the speaker feels bad for his mixed up Greek, so he quotesother peoples perceptions o f his good Greek to establish himself as better sound-

ing than he has just admitted? This is a very plausible query that I cannot rule out.

I do submit, however, that a sidelong glance (in Bakhtins sense) at the other (here

dominant) voice is quite consistent with the overall interpretation of this narrative

segment as expressing conict, tension, and insecurity : all bei ng major features of

internally persuasive discourse. These characteristics are expected to show up as

soon as we step out of the connes (and the protection) of the word of authority:

the domain of non-reexively accepted views (Bourdieus doxa).

REFERENCES

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reections on the Origin and Spread of

Nationalism. London and NewYork: Verso.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin

(Michael Holquist ed., trans. by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist). Austin,Texas:

University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1984. Problems of Dostoevskys Poetics (Caryl Emerson ed. and trans.,

introduction byWayne C. Booth). Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1986. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays (Caryl Emerson andMichael Holquist eds., trans. byVern McGee). Austin,Texas: University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. and Pavel N. Medvedev. 1985. The Formal Method in Literary

Scholarship: A Critical Introduction to Sociological Poetics (trans. by Albert J. Wehrle).

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Benjamin,Walter. [1973] 1992. Illuminations. London: Fontana Press.

Biris, Kostas. 1960. A|"&, o !"|& ou N"oeou Eou. AyZna. (Arva-

nites, the Dorians of Modern Hellenism. Athens).

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (trans. by

Richard Nice). London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power (trans. by Gino Raymond and

MatthewAdamson). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Brandist, Craig S. 2000. Bakhtin and/in cultural studies: Foundations reconsidered.

590 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

23/27

Briggs, Charles L. 1986. Learning How toAsk: A Sociolinguistic Appraisal of the Role of the

Interview in Social Science Research. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Caton, Steven C. 1990. Peaks of Yemen I Summon: Poetry as Cultural Practice in a North

YemeniTribe. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Cmiel, Kenneth. 1990. Democratic Eloquence: The Fight over Popular Speech in

Nineteenth-Century America. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of

California Press.

Coupland, Nikolas. 2001. Language, situation, and the relational self: Theorizing

dialect-style in sociolinguistics. In Penelope Eckert and John R. Rickford (eds.) Style

and SociolinguisticVariation. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. 185^210.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Richard Dauenhauer. 1998. Technical, emotional, and

ideological issues in reversing language shift: Examples from southern Alaska. In

Lenore A. Grenoble and Lindsay J.Whaley (eds.) Endangered L anguages: Current Issues

and Future Prospects. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. 57^98.

Dorian, Nancy C. 1981. Language Death: The Life Cycle of a Scottish Gaelic Dialect .Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Dorian, Nancy C. 1999. The stages of language obsolescence: Stages, surprises,

challenges. Languages and Linguistics 3: 99^122.

Eagleton, Terry. 1976. Criticism and Ideology: Marxist Literary Theory. London and New

York:Verso.

Eagleton,Terry. 1991. Ideology: An Introduction. London and NewYork: Verso.

Empirikos, L., A. Ioannidou, E. Karatzola, L. Baltsiotis, S. Beis, K. Tsitselikis and

D. Christopoulos (eds.). 2001. G!n E"o E (K"nto E"u!

M"ook! O!). An : EkdoseiB AlexandrEia. (Linguistic Alterity in Greece

(Center for the Researches of Minority Groups). Athens: Alexandria Press).Errington, Joseph. 2003. Getting language rights: The rhetorics of language endanger-

ment and loss. American Anthropologist 105: 723^732.

Ferguson, Niall (ed.). 1998. Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals. London

and Papermac, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: TransAtlantic.

Gal, Susan. 1993. Diversity and contestation in linguistic ideologies: German speakers

in Hungary. Language in Society 22: 337^359.

Gal, Susan. 1995. Language and the Arts of Resistance. Cultural Anthropology 10:

407^424.

Gal, Susan and Judith T. Irvine. 1995. The boundaries of languages and disciplines: How

ideologies construct dierence. Social Research 62: 967^1001.

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the La te Modern

Age. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press.

Goman, Erving. 1990. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London:

Penguin Books.

Habermas, Jrgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry

into a Category of Bourgeois Society (trans. by Thomas Burger with the assistance of

Frederick Lawrence). Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press.

Hamp, Eric P. 1978. Problems of multilingualism in small linguistic communities. In

James E. Alatis (ed.) International Dimensions of Bilingual Education (Georgetown

Round Table on Languages and Linguistics). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Univer-

sity Press. 155^164.Hill, Jane H. 1970. Foreign accents, language acquisition, and cerebral dominance

d 4

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 591

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

24/27

Hill, Jane H. 1995. The voices of Don Gabriel: Responsibility and self in a modern

Mexicano narrative. In Dennis Tedlock and Bruce Mannheim (eds.) The Dialogic

Emergence of Culture. Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. 97^147.

Hill, Jane H. 1998.Today there is no respect: Nostalgia,respect, and oppositional dis-

course in Mexicano (Nahuatl) language ideology. In Bambi B. Schieelin, Kathryn A.

Woolard and Paul V. Kroskrity (eds.) Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory. New

York and Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. 68 86.

Holquist, Michael. 1990. Dialogism: Bakhtin and his World. London and New York:

Routledge.

Hymes, Dell. 1974. Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. Philadel-

phia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kroskrity, Paul V. 1998. Arizona Tewa Kiva speech as a manifestation of a dominant

language ideology. In Bambi B. Schieelin, Kathryn A.Woolard and Paul V. Kroskrity

(eds.) Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory. New York and Oxford, U.K.: Oxford Uni-

versity Press. 103 122.Kuipers, Joel C. 1990. Power in Performance: The Creation of Textual Authority in Weyewa

Ritual Speech. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kuipers, Joel C. 1998. Language, Identity, and Marginality in Indonesia: The Changing

Nature of Ritual Speech on the Island of Sumba. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University

Press.

Labov,William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of

Pennsylvania Press.

Laclau, Ernesto and Chantal Moue. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a

Radical Democratic Politics. London and NewYork: Verso.

Mey, Jacob. 1985. Whose Language? A Study in Linguistic Pragmatics. Amsterdam, TheNetherlands and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Philips, Susan Urmston. 1993. The Invisible Culture: Communication in Classroom and

Community on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Wave-

land Press.

Sasse, Hans-Jrgen. 1990. Theory of language death and language decay and contact-

induced change: Similarities and dierences. Arbeitspapier No. 12 (Neue Folge).

Cologne, Germany: Insitut fr Sprachwissenschaft, Universita t zu Ko ln.

Schieelin, Bambi B., Kathryn A. Woolard and Paul V. Kroskrity (eds.). 1998. Language

Ideologies: Practice and Theory. NewYork and Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New

Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Silverstein, Michael. 1981. The limits of awareness. Working Papers in Sociolinguistics

(number 84). Austin,Texas: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Silverstein, Michael. 1985. Language and the culture of gender: At the intersection of

structure, usage, and ideology. In Elizabeth Mertz and Richard J. Parmentier (eds.)

Semiotic Mediation: Sociocultural and Psychological Perspectives. New York and

London: Academic Press. 219^259.

Silverstein, Michael. 1996. Monoglot standard in America: Standardization and meta-

phors of linguistic hegemony. In Donald Brenneis and Ronald K. S. Macaulay (eds.)

The Matrix of Language: Contemporary Linguistic Anthropology. Boulder, Colorado:

Westview Press. 284^306.Taylor, Charles. 1997. H olitikZ tZB anagnorisZB. Epm. Amy Gutmann.

y d l 4 ( b l d

592 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

25/27

Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 1981. Language change and language death in Albanian speech com-

munities in Greece: A sociolinguistic study. PhD dissertation. Madison, Wisconsin:

Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin (Ann Arbor, Michigan,

Microlms).

Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 1988. Language shift and narrative performance: On the structure

and function of Arvan| tika narratives. Language in Society 17: 61 86.

Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 1989. Skewed performance and full performance in language obsoles-

cence: The case of an Albanian variety. In Nancy C. Dorian (ed.) Investigating

Obsolescence: Studies in Language Contraction and Death. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge

University Press. 117^137.

Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 1995. The coding of l inguistic ideology in Arvan|tika (Albanian) lan-

guage shift: Congruent and contradictory discourse. Anthropological Linguistics 37:

541^577.

Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 1998. A Linguistic Anthropology of Praxis and Language Shift:

Arvan|tika (Albanian) and Greek in Contact. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press.Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 2000. Popular conferencing and the public face of linguistic ideology.

Paper presented at the 99th Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological

Association, November 2000, San Francisco, California.

Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 2003. Implicit linguistic ideology and the erasure of Arvan|tika

(Greek-Albanian) discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 35: 539^558.

Urban, Greg. 1991. A Discourse-Centered Approach to Culture: Native South American

Myths and Rituals. Austin,Texas: University of Texas Press.

Voloshinov,Valentin N.1973. Marxism and the Philosophy of Language (trans. by Ladislav

Matejka and I. R.Titunik). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Woolard, Kathryn A. 1985. Language variation and cultural hegemony: Toward anintegration of sociolinguistic and social theory. American Ethnologist 12: 738 748.

APPENDIX

For ease of printing and reading, the data cited here are not transcribed in the

IPA. I have chosen a transcription that overlaps with the Albanian alphabet.

. e stands for the schwa which enjoys a phonemic status in the output of uentArvan| tika speakers

. h stands for the Albanian velar fricative which is more or less systematically

pronounced by uent speakers, and shows up also in their Greek

. rr is also phonemic even though its trilled nature is not always heard clearly

in the tape (hence the parenthesized rendering of r in line 2 of Extract 4)

. kj, gj, lj, nj, sh etc. represent palatal sounds, both stops and fricatives

. Apostrophes, in the original utterances and in the glosses, indicate the

omission of certain sounds in fast speech

. Accent marks are placed over the relevant syllables of non-monosyllabicArvan|tika and Greek words to make the reading of these items easier and

l t t l i ti

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPLICATION OF BAKHTIN 593

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

26/27

. Brackets enclosing dots stand for unclear items in the tape

. Bracketed utterances constitute speakersasides in addressing themselves to

the investigator where relevant

. A series of dots at the beginning of Extract 5 indicates that the cited text hasbeen extracted from a longer speech segment

. Bold letters are used for the transcription of the Greek utterances, unless

the whole text is in Greek, whereas Greek loanwords in Arvan|tika, as mor-

phologically and phonologically adapted by speakers, are left unmarked

. Italics are used in Extract 3 to represent words discussed citationally by the

consultants and myself, and in Extract 6 to represent quoted-reported

speech by the speaker

Given the relaxed attitudes towards the minority language, and hence the lack

of corrective pressures (an outcome of the hegemony of the standard), and

also the constant intergenerational inuences, even uent speakers do not

render phonemic distinctions in a systematic manner all the time. This also

holds true for some of uent-speaker grammar. For instance, verb forms requir-

ing past morphology are not rendered consistently since they should follow

the paradigm of the past [imperfect] tense marking. I have supplied the past

tense semantics in the glosses. Certain grammatical dysuencies ( particularly

those concerning grammatical gender distinctions) in speakers Greek are not

marked in the texts.

Address for correspondence:

Lukas D.Tsitsipis

Department of French, Faculty of Philosophy

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki 54124

Greece

594 TSITSIPIS

-

8/2/2019 sociolinguistics bakhtin

27/27