SOC101Y Introduction to Sociology Professor Robert Brym Lecture #13 Global Inequality 23 Jan 13.

SOC101Y Introduction to Sociology Professor Robert Brym Lecture #5 Networks, Groups & Bureaucracies...

-

Upload

archibald-lewis -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of SOC101Y Introduction to Sociology Professor Robert Brym Lecture #5 Networks, Groups & Bureaucracies...

SOC101YSOC101Y

Introduction to SociologyIntroduction to SociologyProfessor Robert BrymProfessor Robert Brym

Lecture #5Lecture #5Networks, Groups & Networks, Groups &

BureaucraciesBureaucracies10 Oct 1210 Oct 12

Test #1 – 17 Oct 12 Check “Class Announcements” on course website

for test format (updated) and locations. Bring non-programmable calculator and English-

foreign language dictionary. Review last year’s test #1 in “Tests and Exam”

section of course website. Responsible for all material covered in readings,

lectures, handouts, movies, and tutorials. Test covers rote knowledge of the material and

ability to apply it to novel problems and scenarios. Few if any questions on names and percentages;

many questions on trends, ideas and interpretations.

Why Most People Why Most People ConformConform

Norms of solidarity demand conformity.

Structures of authority tend to render people obedient.

Bureaucracies in particular are highly effective structures of authority.

Obedience to Authority Increases Obedience to Authority Increases with Separation from the Negative with Separation from the Negative Effects of One’s ActionsEffects of One’s Actions

0

20

40

60Same room;hand forced

Same room

Different rooms;see and hear

Different rooms;see but not hear

Milgram’s experiment supports the view that separating people from the negative effects of their actions increases the likelihood of compliance. When subject and actor were in the same room and the subject was told to force the actor’s hand onto the electrode, 30% of subjects administered the maximum, 450-volt shock. When subject and actor were merely in the same room, 40% of subjects administered the maximum shock. When subject and actor were in different rooms but the subject could see and hear the actor, 62.5% of subjects administered the maximum shock. When subject and actor were in different rooms and the actor could be seen but not heard, 65% of subjects administered the maximum shock.

Percent of subjects who administered maximum shock

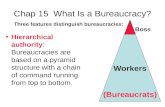

A bureaucracy is a large, impersonal organization composed of many clearly defined positions arranged in a hierarchy. It has a permanent, salaried staff of qualified experts and written goals, rules, and procedures. Staff members always try to find ways of running their organization more efficiently. Efficiency means achieving the bureaucracy’s goals at the least cost.

BureaucracyBureaucracy

A social group is composed of two or people who identify with one another, routinely interact, and adhere to defined norms, roles, and statuses.

A social category is composed of two or more people who share similar status but do not routinely interact or identify with one another.

In a primary group, norms, roles, and statuses are agreed upon but are not put in writing. Social interaction creates strong emotional ties, extends over a long period, and involves a wide range of activities.

A secondary group is larger, and social interaction is more impersonal, creates weaker emotional, extends over a shorter period, and involves a narrow range of activities.

The Asch experiment: Which line in The Asch experiment: Which line in card 2 is the same length as the line card 2 is the same length as the line in card 1?in card 1?

1. Line 12. Line 23. Line 3

Card 1 Card 2

The likelihood of conformity... increases as group size increases to

three or four members; increases in more cohesive groups; is higher among people of low status; is higher in collectivist than in

individualistic cultures; is greater if it appears that nobody is

willing to dissent.

Groupthink is the tendency to conform to group norms despite individual misgivings.

GroupthinkGroupthink

Bystander apathyBystander apathy

Bystander apathy is the tendency of witnesses not to get involved in wrongdoing. As the number of bystanders increases, the likelihood of any one bystander helping decreases because the greater the number of bystanders, the less responsibility any one individual feels.

In-group members are those who belong to a group.

Out-group members are those who do not belong to the group.

An in-group typically draw symbolic, spatial and interactive boundaries separating itself from an out-group and tries to keep out-group members from crossing the boundaries.

In-group and out-group In-group and out-group

Correlation

A variable is a concept that can have more than one value. A correlation is the relationship or association between two variables. The correlation coefficient (r) measures the strength of the association between two variables. Its value ranges from -1 to +1, with -1 indicating a perfect negative linear association, +1 indicating a perfect positive linear association, and 0 indicating no association.

CorrelationsCorrelations

0

20

40

60

0 2 4 6 8

0

20

40

60

0 2 4 6 80

20

40

60

0 2 4 6 8

r = .85(little scatter, strongpositive correlation)

r = -.92(even less scatter, stronger negative correlation)

r = 0 (lots of scatter, no correlation)

Variable y Variable y Variable y

Variable x Variable x Variable x

1. Positive Correlation 2. Negative Correlation 3. No Correlation

Each red diamond in the graphs below indicates a case’s value on two variables, x and y. The straight black lines are “regression lines” that show the linear trend in the data. Each line minimizes the sum of the squared distances between each data point and the line. The correlation coefficient measures the amount of “scatter” around the line.

Correlations may be Correlations may be coincidentalcoincidental Events, including correlations, may be due to

coincidence. For example, you may toss a coin and get

heads, and then toss it again and get heads. The chance of this happening is ½ x ½ = ½2 = ¼. Common sense suggests that these successive events are likely just a coincidence.

However, if you tossed a coin 10 times and got all heads, the chance of this happening is 1/210 = 1/1,024. This is a sufficiently rare event that we suspect the event is not due to chance.

We study statistics partly to know the chance that events, including correlations, are likely to be real or coincidental.

Correlations may be Correlations may be spuriousspurious A correlation may also be spurious (or

phony) if it is preceded by the real cause of the correlation.

Frequency of stork sightings

Fertility rate

Correlation

Frequency of stork sightings

Fertility rate

Rurality

Correlation

Correlation

SPURIOUS RELATIONSHIP NON-SPURIOUS RELATIONSHIP

No correlation

StatisticsStatistics

We must eliminate (or at least sharply reduce) the chance of coincidence and spuriousness before we can conclude that a correlation signifies a causal relationship.

Statistics teaches us how to do these things.