Singapore Food Poster

-

Upload

falon-deimler -

Category

Documents

-

view

7 -

download

2

Transcript of Singapore Food Poster

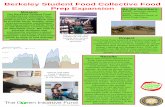

“You Are What You Eat” – Food and Identity:

Authenticity, Modernity, and Ethnic Symbolism

in Singaporean Cuisine

ReferencesBai, Ruoyun. ""Chicken Wings"" Studies in Symbolic Interaction 26 (2003): 263-65. Print.Eugene KB Tan. "Reconceptualizing Chinese Identity: The Politics of Chineseness in Singapore." Ethnic Chinese in Singapore and Malaysia: a Dialogue between Tradition and Modernity. Singapore: Times Academic, 2002. 109-36. Print. Gans, Herbert. 1979. "Symbolic ethnicity: The future of ethnic groups and cultures in America". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2 (1): 1-20.Gaytan M.S. 2008. "From sombreros to sincronizadas: Authenticity, ethnicity, and the Mexican restaurant industry". Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 37 (3): 314-341.Infopedia. National Library Board, Singapore. Web. 20 June 2011. <http://infopedia.nl.sg/>.Kong, Lily. 2007. Singapore hawker centres: people, places, food. Singapore: National Environment Agency.Kiong, Chong, and Kwong. Traditional Chinese Customs in Modern Singapore. Asian Traditions and Modernization, Centre for Advanced Studies, Times Academic Press, Singapore, 1992, pp 78-101.Lim, Shirley Geok-lin. 2004. "Identifying Foods, Identifying Selves". The Massachusetts Review. 45 (3): 297.Lu, Shun, and Gary Alan Fine. "The Presentation of Ethnic Authenticity: Chinese Food as a Social Accomplishment." Sociological Quarterly 36.3 (1995): 535-53. Print. MacCannell, Dean. "Staged Authenticity." The Tourist: a New Theory of the Leisure Class. Berkeley: University of California, 1999. 91-107. Print. My Hawkers.sg. National Environment Agency, 10 Mar. 2010. Web. 20 June 2011. <http://www.myhawkers.sg>. YourSingapore.com - Experience. Singapore Tourism Board, 2010. Web. 01 Aug. 2011. <http://www.yoursingapore.sg/content/ traveller/en/experience.html>.

Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Phua for facilitating this research abroad and mentoring me in the process of conducting sociological research. I would also like to thank Gettysburg College giving me the grant which made this research possible.

ConclusionWhile the production of identity for immigrants via cuisine in America is largely controlled by the demands by an uninformed majority population, the hawker centers of Singapore act as a microcosm of society. They provide younger and older generations with an outlet through which they control the production of identity symbols through interactions and demands as a consumer population, consuming not only food but also preserving the ethnic identities attached to the variations of Indian, Malay, Chinese, and Western cuisine that most hawker centers provide. Minority populations are able to represent and define themselves in Singaporean society through their cuisine.

However, considering the overwhelming pressures of modernity upon the interests and demands of the Singaporean individual, as well as the heavy involvement of the government in the production of images of Singaporean cuisine, lifestyle, and overall identity, it is still possible that the character of Singaporean food has been duly impacted by outside constructs and agendas.

IntroductionSingaporean "Hawker Centers" (food courts) provide a space for the preservation and adaptation of ethnic symbols and identities, as well as a larger Singaporean identity, through the use of food as a symbol of heritage and unity within a highly modern society. I present the experience of Singaporean ethnic identity production via food in contrast to that of immigrant populations in America to reveal the uniqueness of Singaporean identity issues.

Singaporean Hawker CentersDue largely to health problems caused by street vendors during the 1950s and 60s, street hawkers were licensed and relocated into hawker centers by the Singapore government. Now as many as 110 hawker centers exist in Singapore, housing over 15,000 food and drink stalls. Stalls are required to maintain strict sanitation and quality standards. Ratings by the government are made public.

Significance of Food Culture in SingaporeWith eating as a national pastime and a motto of “just queue,” food plays a vital role in Singaporean life.

“The passion we [Singaporeans] have for our local food culture is not just about eating. It says something about our cosmopolitan cultural rojak, bonding, pride, and lifestyles...Our people's culture, history, food and lifestyles are linked inextricably“ (K.F. Seetoh quoted by Geok-Lin Lim, 298)

Immigrant Food Culture in America Consumer demands in American society have compressed most food presentations of ethnic identities into “platefuls of stereotypes,” creating dialogues of difference and misunderstanding that have damaging impacts on those ethnics being represented by the “ethnic cuisine” they are forced to produce.

Results (cont.)"You are What You Eat”: Food as the Mirror

2006 NEA-MCYS survey:• 93.8 percent ate out at hawker centers or brought

food home from hawker centers. • 44 percent ate hawker food once or twice a week, and

one in four respondents claimed to eat at hawker centers three or more times a week (Kong 2007).

The hawker center is embedded in the infrastructure of Singaporean life for all classes. Singapore’s “C-M-I-O-ness”—Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Other—categories of identification, which Singaporean cuisine “taps into,” are clearly reflected in the dishes offered in hawker centers. Among countless others, Haianese chicken rice (Chinese), roti prata (Indian), and nasi goreng (Malay) are examples of this diversity.

Official advertisements for such things as “food heritage” are extremely visible in daily life. One public library presented a semi-interactive display, titled “Delicious Heritage,” which provided accounts of old-day hawkers. Additionally, the Singapore Tourism Board makes notable efforts to promote food to tourists. These advertisements shape the contextual framework from which Singaporeans address food and identity using lenses of idealism and sentimentalism, and national pride.

MethodsData Collection MethodsParticipant observation was conducted in 10 hawker food centers for qualitative analysis. Interviews with Singaporean nationals were transcribed and coded, as were materials from official advertisements, displays, pamphlets, and websites. Relevant articles were referenced for information and to establish theoretical frameworks.

Interview Sampling MethodsUsing the snowball sampling method, a total of 10 individuals were interviewed, with each interview lasting from 30 minutes to an hour. All interviews were conducted face to face. The respondents were of Chinese descent, with one individual of Indian descent. Apart from one Malaysian national, the rest of the individuals were Singapore nationals.

Evaluation of MethodsAs my research was more generally explorative, I encountered little difficulty in conducting interviews. I faced a language barrier when approaching individuals in hawker centers. The representativeness of the interviews could be enhanced with more interviews. The reliability of the information is dependent upon the integrity of the individual respondents and the validity of other sources used.

Falon Deimler, Gettysburg College

Singaporean “Hawker Center”

Singaporean “Chili Crab”

ResultsAuthenticity: “A Matter of Degree”In American ethnic cuisine, there is a “discrepancy…between ideal and acceptance” (Lu and Fine 539), where Chinese food, Mexican food, and others should, ideally, have an authentic character, yet for the sake of practicality, should also be Americanized ethnicity in this generation is highly influenced by convenience. ‘Consumption-oriented’ versus ‘connoisseur-oriented’ dining as it is seen in the United States also appears in Singapore; many people travel for hours for good taste, but often need quick solutions for daily meals. It is possible that the Singaporean hawker center inherently accommodates the demands of both of these distinctions at once, thereby creating a ‘consumption-oriented connoisseur’: the average, every-day Singaporean, a knowledgeable consumer, who demands both efficiency and experience from every meal.

While for American ethnic cuisine, “Old countries are particularly useful as identity symbols because they are far away and cannot make arduous demands on American ethnics" (Gans 10), the close historical and geographical range to those ‘old countries’ for Singaporeans increases vital awareness in what is authentic and what is not, which pressures hawkers to cater to powerful notions of heritage and quality.