0560-0636, Isidorus Hispaliensis, Historia de Regibus Gothorum. Wandalorum Et Suevorum, MLT

'Sicut lex Gothorum continet': Law and Charters in Ninth- and Tenth-Century León and Catalonia

-

Upload

roger-collins -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

Transcript of 'Sicut lex Gothorum continet': Law and Charters in Ninth- and Tenth-Century León and Catalonia

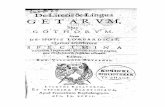

'Sicut lex Gothorum continet': Law and Charters in Ninth- and Tenth-Century León andCataloniaAuthor(s): Roger CollinsSource: The English Historical Review, Vol. 100, No. 396 (Jul., 1985), pp. 489-512Published by: Oxford University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/568233 .

Accessed: 21/12/2014 06:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The EnglishHistorical Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

English Historical Review

? I985 Longman Group Limited London 0013-8266/85/17560488/$03.00

The English Historical Review No. CCCXCVI - July I985

'Sicut lex Gothorum continet': law and charters in ninth- and tenth-century

Leon and Catalonia IT is now sixty years since the publication of D. Claudio Sainchez- Albornoz's brief article first drew attention to the use and importance of the Visigothic law code, the Forum Iudicum or Lex Visigothorum, in the practical working of the courts of the kingdom of Leon.1 Since I924 many, though not all, of the texts upon which a fuller understanding of both the judicial processes and the jurisprudence of that realm in the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries depends have been published, but relatively little work has been done on them.2 On the other hand for Catalonia in the same period, where the law and its procedures were identical in origin and similar in character, considerable study has been undertaken, especially in the last decade, of the role, evolution and final extinction of the use of Lex Visigothorum in the courts of the region.3 But at the same time many of the texts upon which such investigations are or should be based remain unedited and unprinted.

This latter paradox is less surprising when it is considered how substantial are the holdings of original documents of these centuries in the principal Catalan archives, notably the Archivo de la Corona de Aragon and the collections held in the Abbey of Montserrat. On the other hand, for Leon, Galicia, Castille and above all Navarre the number of extant original charters is small, at least in comparison

i. C. Sanchez-Albornoz, 'El juicio del Libro en Le6n durante el siglo X y un feudo castellano del XIII', Anuario de Historia del Dereho Espanol (henceforth A.H.D.E.) i (1924),

pp. 382-90.

2. Amongst the principal editions relevant to this period are A.C. Floriano, Diplomdtica espaiola del periodo astur, 2 vols. (Oviedo, 1949, 19 5I), J. M. Minguez Fernmndez, Coleccidn diplomdtica del monasterio de Sahagun (Le6n, 1976), G. del Ser Quijano, Documentacidn de la Catedral de Ledn (siglos IX-X) (Salamanca, I98I), and for Castille (though many of the early texts need critical reappraisal) L. Serrano, Becerro gdtico de San Pedro de Carde*a (Valladolid, I9IO) and idem, Cartulario de San Pedro de Arlan.Za (Madrid, 1925).

3. The principal studies are A. Iglesia Ferreir6s, 'La creaci6n del derecho en Catalunia', A.H.D.E. xlvii (I977), pp. 99-423, W. Kienast, 'La pervivencia del derecho godo en el sur de Francia y Catalunya', Boletin de la Real Academia de Buenas Letras de Barcelona xxxv (I973/4),

pp. 265-295, and M. Zimmermann, 'L'usage du droit wisigothique en Catalogne du IXe au XIIe siecle: Approches d'une signification culturelle', Melanges de la Casa de Velazquez ix (I973), pp. 233-8I.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

490 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

with Catalonia. For these areas much greater recourse has to be made to documents preserved in the later cartularies, principally of the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries, which are in addition much more easily publishable, though it must be admitted that some of the most interesting of them still remain unedited or only partially printed. Catalonia has also been fortunate in its antiquarians: the voluminous appendices of the Marca Hispanica and Villanueva's Viage Literario have preserved many documents, otherwise no longer extant, and in bulk they far outweigh the quantity of similar materials to be found for example in Espata Sagrada.1 In practice, for records of court proceedings dealing with disputed titles to property from printed texts there are about fifty relevant documents available from the kingdom of Leon, including Galicia and Castille, and roughly the same number from Catalonia. In the case of Catalonia this figure could be substantially increased by a thorough search through the many unpublished documents of the archives - there exist three such from the late tenth century alone in the S. Benet de Bages collection in the archive of Montserrat - whilst it is urilikely that many more Leonese texts of this kind will come to light; though again there are two more in the generally well-known Galician cartulary of Celanova. For the kingdom of Navarre and County of Aragon there exists an original document of 958, preserved in the archive of the Cathedral of Jaca, together with about half a dozen others in cartulary copies.2

For a study of legal principles and procedures, documents con- cerned with property disputes, generally over land, are particularly useful. For one thing they have survived in numbers that are relatively substantial in comparison with most administrative docu- ments other than deeds of sale and gift. The reason for this is simple: the beneficiaries, the victorious parties, had an interest in having them drawn up and then preserving them: they served to provide additional security of title, and, as will be seen, some of them were specifically intended to prevent the resurrection of defeated claims. Thus most of the available texts relate to disputes in which monaster- ies or cathedral churches were involved, as it is generally only their records that have survived. In a small number of cases the documents relate to disputes between laymen over property that only subse- quently passed into ecclesiastical hands. These texts were then deliberately preserved by the subsequent owners because of the importance attached to written title and the danger of old litigation being renewed. Lands that had not been the cause of legal contention

i. Pierre de Marca, Marca Hispanica (Paris, I688); J. de Villanueva, Viage literario a las iglesias de Espana, vols. vi-xv (Madrid, i 8 2 I-i 8 5 I).

2. Ed. R. del Arce, 'El archivo de la Catedral de Jaca', Boletin de la Real Academia de la Historia, lxv (1914), pp. 49-5 i. This and other western Pyrenean texts seem to indicate the existence of substantial differences in legal principles and procedures as between these regions and the rest of the Iberian peninsula, requiring separate study.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 49I

were highly prized, and the fact was often recorded in charters: in one document it is stated that possession of the property had not given rise to dispute for over one hundred years.1

We are, in consequence, relatively well informed as to the procedures whereby conflicts over property were resolved. Other forms of legal record from this period, especially those relating to what we would classify as criminal rather than civil cases, have in general not survived because there was little need or incentive for them to be preserved. One notable and little explored exception to this is the survival of a set of texts in the cartulary of the Galician monastery of Sobrado, recording surrenders of property made to Count Hermenigild, Major-domo to King Ramiro II c. 940, by a surprising number of smallholders unable to pay the substantial fines imposed by judges on them or their offspring for rustling the Count's sheep and cattle or illegally appropriating his land. All of this property he was subsequently to use to found and endow Sobrado, together with his son Bishop Sisenand II of Iria. In con- sequence these documents, nine in number, passed into the mon- astery's archive. The Sobrado collection is not unique in that one or two other such texts survive, but in no other instance is a landowner recorded as obtaining more than one estate in such a manner. It has been suggested that these documents are evidence of a period of disorder and instability in Galicia at this time, the 930S, but it is also possible that these texts, together with a related group of charters recording an equally surprising number of sup- posedly voluntary gifts of property to Hermenigild, give grounds for suspicion as to the methods the Count may have been using to build up the estates he later gave away from the good of his soul.2

Important as these texts are, it is property disputes that give us a clearer lead into the general workings of the law at this time in the two areas under consideration. It will help to begin, taking Catalonia first, by looking at a ninth-century document that might serve to illustrate both the court procedures and the types of record that they produced. In general there are far fewer such texts surviving from the ninth than from the tenth century, but in Catalonia they probably represent the legal system at its most fully developed. The tenth century saw a reduction and simplification, by no means implying an improvement, in the legal procedures or at least the documentation concerned with disputed titles. In Leon the position is almost exactly reversed, with the best texts coming from the tenth century. In both areas and in both periods, however, written evidence of title was, as will be illustrated, the principal though not exclusive foundation for claims to ownership. It is to this that we owe the

i. Archivo de la Catedral de Jaca, pergamino i, ed. cit. p. 49. 2. Cartulario de Sobrado, =Madrid, Archivo Historico Nacional, Codex 977B fos 13V,

14r/v, i6r/V, 25v, 3ir, 36r, 36r-37r.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

492 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

attention to drafting and the preservation not only of our dispute settlement documents, but also of the far more substantial corpus of deeds of gift, sale and exchange, very few of which probably ever involved their possessors in litigation; indeed their very existence was intended to be a protection against it.

On 2I August 843, a judicial assembly, 'in mallo publico', was held in Ampurias under the presidency of Count Adalric and of Gundemar, Bishop of Gerona.1 With them sat various officials and a panel of judges 'qui jussi sunt dirimere causas'. The matter at issue was a dispute over the right to a percentage on various tolls and pasturage dues, and, unusually, the parties in dispute were the two presidents of the court, the Bishop and the Count. This is unusual in that whilst it is not uncommon to find the president of such a court, generally a count, being involved as either complainant or defendant, joint presidencies are rare and this is the only case in which the two were also the disputants. In all such cases, however, the arguments were presented, as in this one, by appointed mandatarii or advocates. At stake was the Bishop's claim to one third of the proceeds of the tolls and dues that were collected by the Count in the counties of Ampurias and Perelada, to which the latter was denying his right. He based his case upon a grant made to his predecessor, Bishop Vimara, by the Emperor Louis the Pious. Once this opening statement of grievance had been made by the Bishop's advocate, and the Count's mandatarius had entered a formal denial of belief in the Bishop's right, the judges asked the former if he had any acceptable proof to support the claim in the form of witnesses and documents - 'testes vel scripturas'. He duly presented the charter of the Emperor granting the bishops of Gerona the right to one third of the 'teloneo' and 'pascuario' of the counties of Ampurias and Perelada. He followed this up by presenting witnesses, men drawn from the local countryside who were both trustworthy and not too poorly endowed with the goods of this world - 'testes veraces homines pagenses perspicui fide atque rebus plentiter opulenti'. These men, interrogated by the judges, stated that they were present - 'vidimus atque praesentes fuimus' (the document represents the various parties speaking in turn in direct speech) - when the imperial diploma was received by the previous bishop. They knew that it granted him the rights now being claimed by his successor, and they had also been present when the bishop presented the order to Count Adalric's predecessor, Count Sunyer, who had then invested the bishop with possession of his rights as instructed.

Once their testimony had been taken, the judges asked Sclua, the Count's mandatarius, if he had any objection to make to any of the bishop's witnesses, and whether he could present either more or better witnesses on his side. To this he had to reply that he could

I. Marca Hispanica, appendix xvi, pp. 779-80.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 493

make no accusations of infamia, that is insufficiency of social standing or notoriety of character (which under Visigothic law prevented a witness's testimony from being acceptable in court) and that for his part he had no witnesses to present. In other words he gave up the case. At this the judges instructed Sclua as the advocate for the losing side to write a professio, also sometimes called an evacuatio, a formal statement recapitulating the outline of the hearing and making a renunciation of the claim on behalf of his principal. Second, they ordered the Conditiones of the witnesses to be written down. This was a full version of their testimony, together with the details of the oaths they had taken as to its veracity. A third document must also have been inscribed, the full account of the hearing from which I have drawn this synopsis, and which ends with the judges declaring that they had conducted the case according to the principles of the Gothic law, a pertinent section of which they quote - 'et Lex Gothorum de hac causa commemorat dicens ...' What they cite is a precis of Liber Iudicum II.ii. 5, though in general in such documents the text is usually quoted verbatim, and on a rare number of occasions the precise reference is noted.1 This document concludes with a formal order to the Count to restore the Bishop to his rights as established by the hearing. Unusually it is not signed by the judges, although it is possible that the scribe of the I2th century Gerona cathedral cartulary, from which this text comes, did not bother to include the final list of signatures.

This case thus produced three documents: the judges' account of the proceedings, the professio of the loser's mandatarius, and the Conditiones Sacramentorum of the witnesses. Fortunately, as well as having the judges' orders for the drawing up of the latter two texts (something not normally included in the documents), we also have one of them preserved in the same Gerona cartulary which contains the judges' account.2 This is the renunciation by the Count's advocate, the professio. Unfortunately the Conditiones of the witnesses have not survived, though the existence of several other examples of such a class of document means that we need not doubt that it did once exist. In general, however, most of the cases of which we know have left us only one document each, and of the three types of document created by a judicial hearing it is the professio or evacuatio that is best represented. The reason for this is not hard to find: such texts, as well as giving a brief synopsis of the hearing, contain the renunciation by the losing party, and were generally so drafted as to be binding upon their heirs and descendants. The possession of

i. The chronological distribution of the giving of such references in charter texts in Catalonia from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries is tabulated in Zimmermann, art. cit. pp. 240-253. His argument that the decline in the provision of precise references after c. io00

marks the diminution in the exact application of the Forum Iudicum is somewhat vitiated by the even greater rarity of such features in the pre-Iooo documents.

2. Marca Hispanica, appendix xvii, pp. 870-8I.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

494 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

such a document thus prevented the subsequent resurrection of a claim, once the dispute had been settled in court. This then was the document that the victor had the most interest in preserving, even to the extent of copying and recopying it into cartularies two or three centuries later. It is indeed possible that in Catalonia in the course of the second half of the tenth century these professiones, which become fuller and more circumstantial in their accounts of the hearings, replace the other documents altogether, and become the sole written record of the resolution of disputes.1

The existence of such records raises a number of interesting points. The explicit citation of Lex Visigothorum which can be paralleled in most of the other texts of this type and also in the later long professiones, is only the most overt feature of the central role of the Visigothic law and particularly of MSS of the code, the Forum Iudicum, in the judicial practices of ninth- and tenth-century Catalonia and Leon. Indeed to some extent such quotations tend to be banal, and to make reference only to what may seem obvious points of procedure. In the case just discussed, the citation merely refers to the obligation on the judge to require the provision of proof by both parties to a dispute. The use of such phrases as 'perquisivimus' and 'legimus' would seem to imply recourse to a written text, but reference is not being made to the code to resolve knotty points of law, but rather to make it explicit that the hearing had been conducted according to the rules of Lex Gothorum; it showed that the procedure had been correct.2 However, more features than such citations indicate the direct relationship between Visigothic law and these judicial hearings; the very drawing up of the documents and the distribution of them is in accordance with a precept of the Forum Iudicum, as is the role played by the witnesses, their oath taking, the general rules of evidence, and the possibility of the use of accusations of infamia to discredit testimony. Lex Visigothorum is very detailed on the latter point.3 It is regrettable that no similar judicial documents have survived from the Visigothic period proper to indicate how far these later texts correspond with the practical application as well as the normative injunctions of the legal system that produced the Forum Iudicum.4 Was there real continuity, a living tradition, or were the Catalan and Leonese judges having to

i. e.g. Viage Literario, xiii, appendices xx, xxii, xxiii, pp. 25-5, 257-260; Iglesia Ferreir6s,

art. Cit. pp. 200-I, is misleading on this class of text. 2. Zimmerman, art. cit. pp. 2 5 1-2 5 3 provides tables indicating the frequency of reference

to the various parts of the Forum Iudicum in the Catalan texts. All references to and citations

of the Code from Catalonia are recorded in the appendix to A. Iglesia Ferreir6s, art. cit., pp.

28 5-423.

3. Lex Visigothorum, II.iv. 4,7,8,I0 ed. K. Zeumer; M.G.H. Legum Sectio I, vol. I,

(Hanover, 1902) (henceforth L.V.), pp. 97, 99-103.

4. For extant legal documents from the Visigothic kingdom, see the fragmentary texts

of A. Canellas L6pez, Diplomdtica Hispano-Visigoda (Zaragoza, 1976) nos. I Iga, 178, 2-29, pp.

I98-9, 245, 275.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 495

reconstruct their procedures just from the rules of the law book, across the gulf of the eighth century? If so there was more than just the code in its various versions to help them. Books of formulae for the composition of legal documents certainly appear to have survived from the Visigothic period. An act of manumission performed by Bishop Rudesind of Dumio (San Rosendo) in 943 used a form of words almost identical to one to be found amongst the collection known as the Formulae Visigothicae, and it included the bestowal of the privilegium of Roman citizenship.1 Similarly, there is a clear parallel between a fragmentary set of Conditiones Sacramentorum inscribed on one of the late sixth-century slate documents found in the vicinity of Salamanca, and most of the ninth- and tenth-century examples of this class of text.2 In addition there exists in the form of Book II of the Forum Iudicum, the longest of the twelve, a detailed guide to procedures, with authoritative statements on such topics as conflicts of evidence and their resolu- tion, the admissibility of witnesses and the conduct of hearings. It is as near as the Early Middle Ages came to producing a written judges' manual.

Returning to the case previously discussed, it is interesting to note that the submission of written evidences - 'scripturae' - was not in itself sufficient to settle the dispute, even though the issue revolved around an imperial grant, and that charter, doubtless properly sealed and attested, was produced in court. One of the great strengths of the Visigothic legal system was the recognition that whilst written evidence had a central role to play in the elucidation of truth, it could not always be relied upon to speak for itself; documents could be forged or, as a case from Galicia in the tenth century indicates, they could be drawn up under duress.3 Hence the importance that was attached to oral evidence being produced in support of written.4 Witnesses had to be provided who could testify from personal experience to the validity of a claim. The formula 'we were present, we saw and we heard', is frequently found in the documents. In this case they were able to testify to their attendance when the charter was presented to the bishop and probably then read aloud to the assembled gathering, thus cor-

i. Cartulario de Celanova, = Madrid, Archivo Historico Nacional, Codex 986B ff. 6ov-6ir; cf. Formulae Visigothicae, no. ii, ed. J. Gil, Miscellanea Wisigothica (Seville, 1972), pp.

72-3.

2. Canellas, op. cit. doc. 38, pp. 141-142; see also M. C. Diaz y Diaz, 'Un document prive de l'Espagne wisigothique sur ardoise', Studi Medievali i (I960), pp. 5 2-71. For examples of the later Conditiones see Viage Literario, xiii, appendices i, iii, xii inter alia for Catalan texts; for a Leonese one see Cartulario de Valpuesta, = Madrid, Archivo Historico Nacional Codex I I66B ff. IV-2v. For the continuing use of the word Sacramentum in its classical sense of oath or pledge, see Isidore, Etymologiae, V.xxiv.3o, as well as its newer Christian significance in Etymologiae, VI.xix. 39-40.

3. Cartulario de Samos, =Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional MS I8387, f.275r/v. 4. L.V. II.iv.3, pp. 95-6.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

496 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

roborating his mandatarius's account of its genesis and contents. The numbers of witnesses appear to have varied both by reason

of availability and the nature of the case. In some instances large numbers of them could be presented, sometimes as many as thirty or more. From the Catalan texts it looks as if all of them were then interrogated and required to take an oath: in the kingdom of Leon it seems to have been more usual for the judges to select a few of them at random, usually only three or four, to act for the rest. The oath-taking ceremony and the formulae employed in the recording of it are common not only to both Catalonia and Leon but also to the preceding Visigothic kingdom.1 The oath-taking was performed in a church, often named in the d9cument, and the indications are that this could be at some distance from where the hearing was being conducted. Unfortunately there are no clear indicators as to where the mallus publicus itself was held. The oaths were taken by the witnesses in the name of the Trinity, then upon the relics of whichever saints were deposited under the altar of the church, and finally upon a Gospel book. Many of the extant Conditiones Sacra- mentorum texts record, like the judges' accounts and the professiones, a summary of the whole judicial proceedings as well as the details of the oath-taking and the witnesses's testimony. Leonese documents make it clear that the processes in the church were conducted for the judges by an officer called the Saio, to a fuller consideration of whom we shall turn. Catalan texts are in this respect generally less informative, but one of them at least makes it certain that as in Leon the oath-taking was supervised by the Saio.2 Stress has already been laid upon the importance of the role of oral evidence, and this applies to virtually all forms of dispute. In the matter of controverted or uncertain boundaries it was the practice in Catalonia for the oldest inhabitants to be interrogated by panels of judges as to their belief and memory of the limits of former estates, and their testimony on this was usually taken on oath.3 These procedures had an important role in the resettling and restructuring of landholdings in Catalonia, both north and south of the Pyrenees, from the late eighth century onwards. Interestingly, the few Leonese texts of this kind record panels of judges performing perambulations to seek out and restore the physical evidence for boundaries, in the form of columns and other kinds of marker, rather than having to make recourse to the memory of witnesses and to oral tradition.4

There is one feature of the judicial procedures, at least in so far

i. Canellas, op. cit. doc. 38, pp. 141-42; L.V. II.i.25 and II.v.12, pp. 71-2, 112-14.

2. Marca Hispanica, appendix xxxix, p. 805: '... sic ordinavimus saionem nomine Nazario qui fecisset ipsos testes jurare, sicut et fecerunt.'

3. On the procedures for determining boundaries in Catalonia, see R.J.H. Collins, 'Charles the Bald and Wifred the Hairy', in Charles the Bald: Court and Kingdom, eds. J. Nelson and M. T. Gibson (Oxford, 1981), pp. 178-179; Marca Hispanica, appendix V, p. 769.

4. Cartulario de Celanova ff. 37v/38r, 39r/v, i62r/v, 173V.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 497

as they are now recorded, which must seem puzzling, and that is the surprising ease with which the apparently rightful claimant wins. The case just outlined is not untypical in this respect. In it the bishop's mandatarius presented both written and verbal testimony: his opponent offered nothing and renounced his principal's claim once the evidence had been produced. Did he and the count know that they had no case? Why did they proceed, without apparently having a scrap of evidence in support of their own contention? In this particular episode it was obviously up to the bishop to establish that he did have a right to what he claimed, as it would otherwise have automatically have remained a perquisite of the count. This case served to test the bishop's title: almost a quo warranto inquest. But this is exceptional. In other cases there were genuine conflicts based on alternative claims of title, but even in these disputes, after the two parties had made opening statements giving their respective stories, when it came to the presentation of evidence only one side produced it.' There were certainly some proceedings that were clearly only intended to be formal, and were undertaken with the aim of obtaining an authorized written text. Thus oral wills could be attested to by witnesses in front of a court in order that a written version should thus be drawn up in the form of conditiones sacra- mentorum.2 It is possible that some of the disputes that were heard before the judges but went uncontested were not real conflicts, but were deliberately intended to test or to obtain written t-itles to property. One case in point is probably represented by three com- plementary sets of conditiones sacramentorum relating to three separate parcels of estates, which confirmed their being owned by the monastery of Eixalda, after the destruction by flood of the latter's buildings had forced the move to a new site at Cuxa.3 The monastery's charters were lost in the flooding but the written conditiones could serve as replacements. This same episode also produced a genuine dispute, in which a former donor, knowing his deed of gift to have been destroyed in the flood, attempted to revoke his donation by claiming that it had never been made. The oral

i. There are a small number of exceptions: Viage Literario, xii, appendix xvi bis, pp. 241-3, and xv, appendix xxxiv, pp. 28o-I describe hearings in which both parties produced documents; Becerro gdtico de Cardena, ed. Serrano, doc. xcviii, p. I13, relates to a case of perjury, and doc. ccx, pp. 224-5, reveals one party to a dispute attempting a bluff with non-existent deeds. However, the general tendency for cases to go uncontested when they have reached the stage of the providing of proof is marked in legal records from other parts of Europe, e.g. C. Manaresi, I Placiti del 'Regnum Italiae', vol. i (Rome, I95 5) no. 6, pp. 14-18

amongst numerous other examples in that collection. I suspect, though, that these disputes were genuine, and that the procedures were not merely being used to obtain written title, except in a small number of cases: cf. n. 3 and p. 498 n. I infra.

2. e.g. Cartulario de Sant Cugat' del Valles, ed. J. Rius Serra (Barcelona, 1945, 1947), vol. i, docs. 139 and 171, pp. 115-lI8, 142-144; these date to 98I and 985 respectively, and would seem to disprove Zimmermann's assertion, art. cit. p. 26i, that the earliest such text dates from 1034.

3. Marca Hispanica, appendices xxxix-xli, pp. 804-I I.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

498 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

testimony of the witnesses told against him, and his evacuatio was thereafter preserved in the Cuxa cartulary.1 This certainly indicates the importance to landowners of the possession of scripturae; another generation and there might have been no witnesses living to have been able to controvert such a claim.

The lack of conflicts of evidence as opposed to conflicts of assertion is marked even in what must have been quite hotly contested cases. One such is a hearing to determine the claim to free status made by a certain Laurence, whom Count Miro of Rossello, brother of the Count-Marquis Wifred I the Hairy, insisted was a servus fiscalis and therefore his property.2 Perhaps surprisingly, and certainly a testimony to the quality of Catalan justice, Laurence won his case even though Miro presided over the court. This case, more lab- oriously argued than most in respect of the basis of the conflicting claims, was speedily resolved when it came to the production of evidence: Laurence could produce witnesses whilst the count's mandatarius could not. Are we to believe that in these hearings the fear of spiritual sanctions as implied by the oath-taking acted as an effective counter to perjury? Why in no extant record do we find the other party producing the 'more and better witnesses' that the judges ask them for? The same phenomenon is equally marked in the Leonese documents, but these and the procedures that they embody are even more complex than those of Catalonia. To under- stand them detailed discussion of a model case may help. One particularly long document, preserved as an original in the Archive of the Cathedral of Oviedo and dating from 953, provides an unusually comprehensive account of a hearing in its various stages.3 It is initially very different to anything preserved in Catalonia. The text starts with an undertaking by the two parties, Peter, abbot of the monastery of Severo, the plaintiff 'qui acsere, in sua voce', and the respondant Wiliefred, 'qui respondet', acting for a certain Victinus, that they would present themselves before the judges named in the document on 6 November 953. This pledge is made to a Saio called Karosus. It is immediately followed by a statement of Peter's grievance, which is that Victinus, having at first endowed him with a monastery and additional property in the form of vacant lands - 'terra vagua' - subsequently repossessed the gift, evicting Peter from the monastery and from a church which Peter had inherited from his own grandfather, and had taken them over

I. ibid. appendix lx, pp. 835-6. Great care was taken to make copies if an original were at all endangered, e.g. Archivo de Montserrat, col. San Benet de Bages doc. 45, a copy made in IOI7 of an evacuatio of 990, deteriorating because the first scribe had not used 'tinctum optimum'.

z. Marca Hispanica, appendix xxxiv, pp. 796-7. 3. Archivo de la Catedral de Oviedo serie B, Carpeta i, no. I I; ed. S. Garcia Larragueta,

Coleccidn de documentos de la Catedral de Oviedo (Oviedo, I962), pp. I03-IO7; on the case see also J. Rodriguez, Ordoio III (Le6n, I982), pp. I7I-8.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 499

himself. By one of the stylistic sleights of hand with which these documents are full, Peter's complaint becomes Wiliefred's admission of guilt on behalf of Victinus. This is immediately followed by a statement by thirty witnesses testifying on Peter's behalf. As with similar Catalan examples it begins with an affirmation of their physi- cal presence during the course of the crucial events: 'we saw with our eyes and were present when ...'. Their account here ends with the signatures of three of them. There follows a repetition of their statement, but prefaced by a preamble which says that these are the conditiones sacramentorum that the witnesses had sworn to by order of the judges, and their oath was 'by the twelve prophets and by the twelve apostles and by the four Gospels, that is Mark, Matthew, Luke and John ... and by the relics of the Blessed Virgin Mary, mother of Our Lord Jesus Christ ... and by the relics of the virgin Saint Marina'. The place where the oath was taken is mentioned towards the end of the section as being 'the church of St Mary outside the gate of Gordo'. At this point there follows an element apparently lacking in Catalan procedure or at least documentation: one of the witnesses is required to undertake the ordeal by hot water, the pena caldaria, as confirmation of the veracity and good faith of their testimony. What looks like a separate section of the document contains the signatures of witnesses to the fact that three days after the performance of the ordeal, Fredenandus, who had undergone it, showed his hand and it was seen to be unmarked - 'limpidus'. This is attested to by three signatories described as being acceptable to both parties - 'fideles de amborum partibus'; two of them signed at the request of Peter, and the third, who had been given custody of Fredenandus, acted as the representative of Wiliefredus, mandatarius of the defeated Victinus. Their attestation is dated zo November, two weeks after the hearing, an interesting indication of the time scale of the proceedings. The statement concerning the ordeal is also witnessed by various clerical and lay 'boni homines' who were present, and by the Saio Karosus, under whose supervision the ordeal had been conducted.

There then follow two joint agreements by the contending parties, Peter and Wiliefred, mandatarius of Victinus, which in the document are entitled placita, and which are addressed, like the opening section of the text, to the Saio Karosus. In the first they promise to present themselves again before the judges at Gordo on the following Saturday, that there Wiliefred would present apactum, and that Peter would be there to receive it 'per manum Saionis'. This pactum, 'quantum lex mandavit', can only be the losing party's statement of renunciation, the equivalent of the Catalan professio or evacuatio, the making of which Forum Judicum specifically commands. This would be formally entrusted to the Saio, and, again as the Visigothic law enjoins, handed by him to the victorious plaintiff. The second under-

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

500 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

taking was for the two parties to meet again, this time in the estates that had been under dispute, where Wiliefredus would once more formally surrender them to the Saio, and they would then be returned by him to Peter. If either of them failed to appear at either of these two occasions, they agreed that he would be liable to pay a fine of five solidi. Both agreements were signed by the two parties.

There then ensues in the document an impressive collection of confirmatory signatures to the whole, including those of the bishops of Leon, Dumio and Oviedo, and of King Ordofio III and of his successor King Sancho I the Fat. This latter, in which he is entitled 'serenissimus princeps', must have been added subsequent to his accession in 956, three years after the events described in the document. There is also, perhaps even more interestingly, the signature of Princess Elvira, daughter of Ramiro II and sister of the two kings, who, it has been argued on the evidence of another dispute document, was entrusted in her monastery with the custody of what was accepted as the definitive text of the Forum Judicum, to which recourse might be made for authoritative readings.1 Finally in this long and complicated document comes a confirmation from a generation later. It is dated 98 I, and is in the form of a recognition, made at Lena in the Church of St Eulalia by the lady Florentina, who was also acting on behalf of a Lady Cogina, that the judgement given against Victinus was rightful. This was witnessed by three priests, the last of whom Donnidus, acted as notary - 'Donnido presbiter cet noduit'. It is a reasonable supposition, though nowhere stated in the text, that these ladies were Victinus's heirs, and under whatever pressure, added this codicil by way of an additional renunciation by the family of any claim to the disputed monastery and land.

As it stands this document may seem indigestible when taken as a whole and when compared with the more clearly defined and differentiated character of the Catalan materials. In its general nature it is not dissimilar to other extant Leonese legal texts, and is principally remarkable for its greater length and comprehensiveness. Like many of the others, it breaks down into distinct component parts, and makes more sense when treated as a set of separate documents that have been run together. These components consist of: first the promise to the Saio by the two parties to come before the judges for a hearing, second, a record of that hearing that includes the testimony of the witnesses, third, the conditiones sacramentorum, fourth, a statement made by chosen witnesses, that the ordeal had successfully been undertaken by a representative of the men who had made the conditiones, fifth, the agreement of the two parties to reappear before the judges, at which point the loser would submit his placitum via the Saio to the victor, sixth, a similar agreement by

i. Rodriguez, op. cit. pp. I 5 9, I 6 S n. I 4.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 501

the two parties to meet the Saio to carry out the restitution, and finally, after a set of confirmations, a recognition by the probable descendants of the unsuccessful defendant.

Did all of these once exist as separate documents? It is quite easy to conceive that our extant single text was compiled from such disparate pieces into an overall account of the salient features of the case, and then duly witnessed, i.e. as a kind of victor's transcript; or alternatively such a document could have been created at the time of the final recognition by Victinus's heirs as the vehicle for that obviously important confirmation. It is interesting to note that one text that is actually mentioned in the document is not preserved, and that is the pactum, the professio that Wiliefredus agreed to make on behalf of Victinus at the end of the proceedings, accepting his judicial defeat. It is possible that it is the loss of that key text which made the obtaining of the recognition by Florentina and Cogina necessary.

It may be questioned whether our document was drawn up by recourse to some six or seven other written texts created by the proceedings or whether it was rather the sole record of them, as it certainly is now. Such a query could have been made about the first of the Catalan documents, previously discussed, which by itself seemed to provide a full and sufficient account of the hearing it describes. Fortunately in that case the survival of the evacuatio, together with the judges' clear statement about the texts they had ordered to be written, makes it certain that several documents were produced. Such proof is not so easy to come by for Leon. In general, as has been mentioned, fewer dispute settlement texts have survived from the kingdom than from Catalonia and more of them are to be found as cartulary copies than as originals. Some of the cartularies are peculiarly rich in such texts, notably that of the Galician monastery of Celanova (still regrettably unedited, though some of its legal documents have recently been published by the indefatigable Professor Sa'nchez-Albornoz).1 Amongst these is one, almost the only one, that can show that Leonese procedures were as prolific in the practical as well as theoretical production of documents as those of Catalonia. The printed text is of a composite document consisting of two parts, related renunciations by the principals of one party to a dispute and by their mandatarius. However, elsewhere in the cartulary I have found another document that provides a similar but not identical version of the first section of the one edited by Sa'nchez-Albornoz.2 It is sufficiently different, containing such

I. C. Sanchez-Albornoz, 'Documentos para el estudio del procedimiento judicial en el Reino Asturleones' in Homenaje a D. Agustin Millares Carlo (Las Palmas, I975), vol. ii, pp. I43-56.

z. ibid. doc. IX, = Cartulario de Celanova fos. 38v/39r; with which compare the un- published text on fo. 54r. The same cartulary contains a similar set of parallel documents, this time produced by a boundary dispute, on fos. 37v/38r and i6zr/v.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

502 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

additional details as the patronymic of the mandatarius of the monastery, together with significant changes in word order and spelling, to show that it is not just a copy of the other text. It certainly indicates that more than one example was made of some if not all of the documents that resulted from the hearing. Additionally, in the case previously outlined, it is hard to envisage how the document as we now have it, covering stages separated in time and place and with the character it has, could have been drawn up without its scribe having written texts before him of the different parts of the procedure, each with its own individual set of witness signatures. I suspect then that Leonese legal procedures did produce a multiplicity of written documents in even greater profusion than those of Catalonia.

This matches the complexity of the proceedings themselves. In the Oviedo document the opening promise to the Saio is the only reflection of the initial step, but a text in the Becerro of the monastery of Sahaguin provides a little more detail from another case.1 This document, also important for its dated reference to the first entry of King Ordofio IV the Bad into Leon, records a dispute between the monastery of Sahagu'n and the wife and sons of a certain Vigila over the possession of Monte de Cerecedo. Both sides appointed mandatarii to speak for them, and these presented themselves to outline their respective cases before Bishop Gonzalo and the king's judges - 'iudices regis' - on 9 June 958. They were then instructed to return on the Saturday after the Kalends of August and to bring with them their cartas, charters, the written evidence on which the conflicting evidence was based. If either party failed to appear they would be held liable for a fine of i oo solidi. In the event the mandatarius of the family of Vigila did not appear, whilst the monks' representa- tive did, and the document records that he stayed with the judges from three days before the date of the hearing until three days after. The case having thus gone by default, the judges permitted the monastery to take possession of the disputed territory in perpetuity, in a decision made on I 3 August.

Thus the first stage is a preliminary hearing followed by an adjournment to a second date, in this case nearly two months later, at which point the production of evidence was required. It is not unreasonable to assume that the adjournment was accompanied by the writing of an undertaking by the two parties to reappear as required, as evidenced in the first section of the Oviedo document. How effectively the fine for failure to attend might be enforced is not known; in the Sahagiun case the fate of the family of Vigila is not recorded. The second stage, the presentation of the evidence,

i. Madrid, Archivo Historico Nacional, Codex 989B fo. I5sr/v; ed. Minguez, Coleccidn diplomdtica, doc. I 5 9, pp. I 97-8.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 503

is very similar to that recognizable in the Catalan documents. In general it is seen that only one of the parties actually produces charters and/or witnesses. In some instances, as in the case just mentioned, the representatives of the side certain of defeat might not even attend, although facing the prospect of a heavy fine. More substantial litigants might in the circumstances resort to even more extreme measures such as joining the rebellions that were almost endemic in Galicia, or taking refuge in the frontier zones of Castille and Portugal beyond the reach of royal justice. A case from 995 throws light on some of the problems this could cause: in a dispute to be judged before King Vermudo II the Gouty between one Erusfoziz and a certain Osorius Iohanniz, the former was obliged to put up afideiussor.1 This was a man called Odoarius, and he was given custody of an estate to be held as a pledge for Erusfoziz's appearance at the subsequent hearing 'quod lex catholica docuisset'. The reason for this particular procedure was that Erusfoziz, although probably a man of some material standing, was held to be 'homo segnis et non verus nec dilectus hominibus'. Segnis (recte seguis) implies disloyalty, and may well indicate that Erusfoziz had pre- viously been implicated in some act of rebellion.2 He was thus, as Lex Visigothorum would see it, tainted with infamia, and his testimony was not by itself acceptable at law.3 He was, as in this instance, required to back his pledges with concrete guarantees. Rightly so, since rather than appearing at the hearing he fled and joined rebels then active in Galicia against the king. As a result all of his property was forfeit to the monarch 'sicut in canonem et lex gotica docuisset' (the text then cites Forum Iudicum II.i.8). But what of the estate entrusted to the fideiussor, which the plaintiff Osorius then sought to claim, and around which the proposed hearing might have been intended to revolve? In the event Osorius and the fideiussor agreed to put the matter before the king, whose title to the estate was also involved. When Odoarius affirmed the sequence of events on oath, Vermudo II made a formal grant of the estate to Osorius.

Returning to the stages of the procedure, after the effective resolution of a case before the judges, the testimony of the witnesses was formalized on a subsequent date by their taking of an oath under the direction of a Saio. At this point there appears a definite divide between Leonese and Catalan practice; in the former, and this is clear from several documents, one of the witnesses was required to undergo an ordeal. In Catalonia reference to the pena caldaria is very rare and is only found in contexts where other forms

i. Cartulario de Celanova, fo. 77r; ed. L. Barrau-Dihigo, 'Chartes royales Leonaises, 9I2-Io37', Revue Hispanique x (0903), doc. 35, pp. 439-4I. For Osorius' gift of the estate to Celanova in IooI, see fos. 84v/85r of the cartulary.

z. J. F. Niermeyer, Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus (Leiden, I976), p. 954 under 'seguis'. 3. L.V. II.iv.8, pp. IoI-ioz.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

504 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

of evidence are either unavailable or insufficient.' In the Leonese kingdom it is standard procedure, and strangely enough, it seems to imply that the witnesses' oath, taken on Gospels and relics, was not held to be sufficient assurance of their veracity. This is certainly the implication of the texts; the Oviedo example reads: 'these testimonies were sworn in the Church of St Maria outside the Gate of Gordo, and for the swearing of them an innocent man by name of Fredenandus entered into the pena caldaria, who on the third day appeared clean in the midst of many witnesses'. Fredenandus himself signed this section of the text recording the successful outcome of the ordeal as follows: 'Fredenandus, who was innocent and swore to this series of conditiones and put his hand into the kaldaria and took it out, and on the third day appeared clean in the assembly'.2 The ordeal is a very late feature in Visigothic law proper: the only reference to it in the Forum Iudicum comes in a law of Egica, which one of the MSS ascribes instead to his son Wittiza, and is in itself neither very full nor very explicit.3 Another MS of the code, dated 1058 and probably written in Leon, supplements this law with instructions as to the procedure of the ordeal: three stones have to be placed in the hot water and then extracted by the examinee using his right hand. The examination was invalidated if he did not bring out two or three of the stones in one go.4 As the documents show, the hand thus used had to be exposed in a public assembly on the third day following, and had to be seen to be unmarked. There also survive examples of liturgical exorcisms performed over the water prior to the carrying out of the ordeal.5 The indications of the law of Egica or Wittiza and of one of these exorcisms, contained in a ninth- or early tenth-century legal compilation, possibly a judge's private handbook (priests and abbots not uncommonly being found serving as judges) suggest that the earliest use of the ordeal in the Visigothic legal system was in the context of criminal trials, and that it was the accused who was obliged to undertake it.6 Its use in the authentification of conditiones in the kind of dispute being examined here looks to be a later development, and a distinctively Leonese feature, as its non-appearance in such a context in the Catalan documents would suggest.

Equally absent from the Catalan records are the final stages of

i. As indicated in Viage Literario, viii, appendix xxxi, pp. z83-5; see also Iglesia Ferreir6s,

art. cit. pp. I93-7.

z. ed. Larragueta, pp. I05-Io6.

3. L. V. VI.i. 3, pp. 2 50-5 I.-

4. ed. K. Zeumer, Leges Visigothorum, p. 463, but for the dating see M. C. Diaz y Diaz,

'La Lex Visigothorum y sus manuscritos - un ensayo de reinterpretacion', A.H.D.E. xlvi

(1976), pp. I63-223, especially p. I64.

5. Canellas, op. cit. doc. 223, pp. 27I-2.

6. Canellas, op. cit. doc. 223, pp. 27I-2, found in MS Holkham 2iO, on which see Zeumer's

edition of Leges Visigothorum p. xx (= MS R3).

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 505

the Leonese procedures: the third appearance of the parties before the judges in which the loser presents his submission, and their concluding meeting with the Saio to carry out the sentence of the court. It is conceivable that the Catalan evacuationes were formally presented as in the Leonese courts, but there are no texts to prove it. Nothing like the administrative placita, the promises and agree- ments made by the parties involved to the Saio, usually addressed as 'our Saio', are to be found in Catalonia. In general the role of the Saio in the Leonese processes is strongly emphasized in the documents. He serves as a kind of executive officer of the court, receiving the written agreements, supervising the oath-taking and the ordeal, held at a different site to the main hearing, and overseeing the making of the submission and restitution by the defeated party. It is possible that in this area the Leonese texts may shed additional light on the Catalan ones. In virtually all of the latter, when at the commencement of the document the judges are listed together with the ecclesiastical and lay 'boni homines', one of the laymen is qualified with the title of Saio.1 In the Catalan texts these Saiones are not given any special role, but as has been shown the kind of documents in which they feature so prominently in the kingdom of Leon do not have any parallel in the Catalan counties. Their specially marked presence must indicate that they had some functions to perform, and it is not unreasonable to suggest that the preliminary and terminal stages of the proceedings, in which Leonese Saiones had a central role, may have had equivalents in Catalonia too. Certainly there are indications that they supervised the oath-taking.

There is an obvious question raised by the prolific making of documents in both Catalonia and Leon that requires an answer: who made them? For the Catalan counties in the tenth century, the surviving originals and the subscriptions to documents preserved in the cartularies make it clear that the texts were in these cases written by the beneficiaries. Virtually all of them have a final signature by their scribe, who in many instances can also be found to have written other documents of different types for the same monastery; in some cases such scribes also sign as witnesses to other charters that they had not written.2 In other words they were monks

I. e.g. Viage Literario, xiii, appendix i (I.6 should read Saione not Salone), appendix iii, appendix xii (Sagone), appendix xxiii (Salone).

z. See for example R. d'Abadal i de Vinyals, Catalunya Carolingia iii pt. ii (Barcelona, 195 5) doc. i88 (of 962), p. 383, written for and signed by Bardina, mandatarius and also prior of the victorious monastery 'qui isto judicio rogavit scribere et judices firmare'. For examples of scribes of such documents coming from the monasteries involved, see F. Udina Martorell, El Archivo Condal de Barcelona en los siglos IX-X (Barcelona, I95 I): Nantulf, scribe of doc. I6, p. I3I (of 904 A.D.), witnesses docs. I9 (of 906) and 38 (of 9I3), and features as a 'Bonus Homo' in the case recorded in doc. 35 (of 9I3), p. I54; likewise Gentiles, the scribe of doc. 35, and also of no 53 (of 9I7) also wrote many of the other non-judicial documents of S. Juan at this time, e.g. docs. 27-9, 32, 34-8, 4I, 42 etc.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

506 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

of the house for which they were writing. This should perhaps be paralleled by the tendency, already mentioned, in the same period in favour of the reduction of diversity in judicial records, and the emergence by the end of the century of an extended version of the evacuatio as virtually the only form of such texts preserved. On the other hand, there are one or two tenth-century Catalan documents explicitly written by one of the presiding judges, and the judicial decree of 843, previously discussed in detail, has no scribal signa- ture.1 Additionally it contains the judges' instructions for the inscribing of the conditiones sacramentorum and of the professio. Similarly in Leon in the ninth and tenth centuries most of the documents are unsigned; the one considered above, with its final 'noduit', is exceptional in this respect, and its peculiar character and the possible circumstances of its composition have been discussed. In general, in view of the many and varied forms of document created by a Leonese hearing, and taking the explicit statement of the Catalan judges of 843, it looks as if in the kingdom of Leon in the ninth and tenth and in Catalonia for at least some of the ninth and possibly part of the tenth centuries, legal records were made publicly by court notaries, perhaps as part of the proceedings. This is also what the rules of Forum Judicum, instructing judges to present copies of testimonies and professiones to the successful party, would have required.2 However, in Catalonia it obviously became in- creasingly common or necessary for the victor to draw up his own record, probably on the spot, and get it signed by judges and confirmatory witnesses.

By and large, and with the notable exception of the ordeal, the theory and practice of the law as administered in the courts was similar in both regions. There are some other important similarities to which attention should be drawn. In both areas the courts were controlled by panels of judges, usually about half a dozen in number, who look to have been professionals, as their frequent citations of Forum Judicum would indicate.3 How and where they received their training is unknown.4 It was the judges, not their prestigious presidents, who carried out the questioning in court and issued instructions. Rare as is the evidence, the indications are that such panels of judges operated upon a regular basis. Two different Catalan cases from one area, separated by a three-year gap, were heard by the same group of judges, with only one of those present on the

I. e.g. Viage Literario, xv, appendix xxxiv (of 988), in which the final signature is recorded: 'Eroigus presbiter quodnomenato Marco qui et judex qui haec scripsi et subscripsi'. p. z8I.

z. L.V. II.i.25, pp. 7I-2.

3. For the full listing of such citations in Catalonia, see the appendix to Iglesia Ferreir6s, art. cit. No such survey has been carried out on the Leonese texts.

4. R. Gibert, 'Enseiianza dcl derecho en Hispania durante los siglos VI a XI', Ius Romanum Medii Aevi, pars I. 5 (Milan, I 967).

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 507

first occasion not reappearing on the second.1 In both areas it looks as if the Mallus Publicus was a regular occurrence, held frequently, as the implications of some of the trials would suggest - each one requiring at least three meetings, separated in time. Nor were the holding of such hearings confined to royal or comital palaces. Each of the Catalan counties looks to have had at least one panel of judges, and the judicial assemblies were certainly held at more than one site.2 Likewise the role of the mandatarius, or assertor as he was sometimes called, was common to both Leon and Catalonia, and is indicative of the existence of a class of at least part-time advocates. Where evidence is moderately plentiful, as in the case of the San Juan de las Abadessas charters preserved in Barcelona, it can indicate that a major monastic house might well use more than one assertor, and that each may be found appearing in several cases on its behalf.3

Control of jurisdiction is a harder matter to be sure about. It is clear in Catalonia that although most courts were conducted under the authority of the local count, who usually presided or was deputised for by a viscount, there were private jurisdictions. Amongst the most important of these was that of the Abbess of San Juan de las Abadessas, whose right derived from a charter of immunity granted by Charles the Simple, probably by request of Count Wifred the Hairy of Barcelona, the founder of the house.4 His daughter Emmo was its first abbess, and her authority was unsuccessfully contested by two of her brothers, the joint Count- Marquises Miro and Sunyer, in 913. A subsequent document of 917 finds Emmo presiding over her own court.5 In Leon the indications are that in theory at least jurisdiction remained a royal monopoly. In many of the legal documents the judges are qualified as being 'of the king', or as being specially appointed by him either for the particular occasion or to serve the legal interests of a special group, as for example is the case with one 'Menendus Uestrimiriz who is the judge constituted by order of King Alfonso [V] for the men who were in the monastery of St Saviour' and who seems to have

i. Marca Hispanica, appendix xxxix (of 879 A.D.), pp. 804-5, and appendix lx (which should be dated 883, not 90I), pp. 835-6; similarly see Catalunya Carolingia, 111.z, docs. II3

and I34 (of 9g0 and 923 respectively) in which four out of seven of the panel of judges in the 9g0 case reappear together in 923 (pp. 342, 353-4).

z. e.g. in the small county of Ampurias, as well as in the town of Ampurias itself (Marca Hispanica, appendix xvi, and Viage Literario, xiii, appendix iii) a 'Mallus Publicus' is found being held 'in villare quod dicitur Purtos' - Viage Literario, xiii, appendix vi. Similarly in the County of Besali judicial assemblies can be found to have been held in small rural sites such as 'in villa Expondeliano', Viage Literario, xiii, appendix xii.

3. Udina Martorell, Archivo Condal, docs. I6 (of 904), 38 (of 9I3) and appendix IIA (of 9I 3) for the Assertor 'Hictor', and docs. 35 (of 9I 3) and 53 (of 9I7) for the Assertor Sclua.

4. ibid. docs. 38, 53 and appendix iia, pp. I57-65, I82-3, 442-3.

5. ibid. doc. 53, pp. I82-3.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

508 SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET: July

ordered the holding of a trial on their behalf in ioi9.1 On the other hand the rise of Castille seems in this, as in several other respects, to have been marked by a real diminution of royal authority in favour of that of the count. In 944 a dispute broke out over control of the monastery of San Salvador de Loberuela, in the course of which by use of forged charters - 'cartas falsarias' - on the part of the 'insidiatores', the monks were evicted. On their complaining an enquiry was ordered by the Count of Castille Assur Fernandez, to be conducted by his uncle, the Abbot Rodanius, by another abbot and by unnamed 'magnati palatii'. This uncovered the truth and restored the dispossessed monks. Surprisingly, this episode is only recorded in a deed of sale by the count to the monks of a church in return for two stallions, two saddles and ten mares - a relatively high price.2 It would be going too far to suggest that this was buying justice, but the episode demonstrates that obtaining it did depend upon gaining the interest of the count. It is interesting also to note that the case turned upon false charters, indicative of the importance of written evidence and its procedures even in Castille, where it is sometimes falsely asserted that a different legal tradition flourished.3 It is particularly regrettable that no fuller account of this episode has survived, as it is one of the few cases known to have produced a genuine conflict of evidence.

As this hybrid document shows, it is not just the fairly limited number of surviving dispute settlement documents that delineate the workings of the law in ninth and tenth century Catalonia and Leon and in particular the central role of the Forum Iudicum. Many straightforward deeds of gift and endowment make reference to the latter, especially when family property was being donated to monasteries. The ruling of Lex Visigothorum that a man who had no sons might do with his goods as he wished was often quoted in charter preambles, as for example in several of the texts preserved in the Celanova cartulary.4 Further indications of the importance of the Code as a written text with a practical value can be found not only in the extant MSS of it, most of which date from the ninth, tenth and early eleventh centuries, but also in the relatively numerous bequests of copies of it to be found in testaments and wills from

I. Sanchez-Albornoz, 'Documentos para el estudio del procedimiento', doc. x, from the Archive of Lugo Cathedral.

z. Ed. J. del Alamo, Coleccidn diplomdtica de San Salvador de Ona (Madrid, I95o) doc. 3, pp. 4-6. For a case from Castille that indicates that the profits of justice went to the Count, see Becerro gdtico de Cardeia, ed. Serrano, doc. xcviii (of 972), p. I I 3.

3. Most recently in M. Marquez-Sterling, Fernan Gontalet, First Count of Castile (University, Mississipi, i980), pp. 28-32, though the 'classic' elaboration may be found in J. Perez de Urbel, Historia del Condado de Castilla, 3 vols. (Madrid, I945), vol. i, pp. I 5o-65.

4. Cartulario de Celanova fos. z7r, 63r, 78v; the absence of such a formula from similar documents in, for example, the Cartulary of Sobrado may reflect local variations in notarial training and practices.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 509

Catalonia, Galicia and Le6n.' One of these is of particular interest: a lady Adosinda, wife of the Galician Count Gonzalo Pelaez, made an extensive gift of property to the monastery of St Martin de Lalin in IOI9, which included a collection of books, amongst which is to be found a copy of the Liber Iudicum. It is perhaps not coincidental that her father seems to have been a certain Gudesteus Judex, whose judicial activity is recorded in the same area in documents of the 990s.2 This is the sole, though hardly surprising, indication that a judge might, as the title of the work implies, have possessed his own copy of the Code.

All of this material, the MSS, glosses on the text, the testamentary references and the role of Lex Visigothorum as evidenced in literally hundreds of other charters of various types, could receive and certainly deserves fuller and more detailed exposition than can be provided here, but its very existence may help to suggest an additional dimension of scale for the much more limited corpus of texts relating to court cases. A further indicator might be mentioned in passing, and that is the statement in the Chronicle of Sampiro that King Vermudo II of Le6n confirmed the Visigothic laws: 'leges a Vambano principe conditas firmavit'.3 He did the same for the canon law. The apparent reference to Wamba, who of all the late Visigothic kings is credited with the least legislation and with no responsibility for a code, may seem surprising. However, inscriptions found in some late tenth and eleventh century Leonese MSS show that a confusion could be made at that time between the names of Wamba and of Egica, who in the Leonese historiographical tradition were also held to be related.4 It is highly probable that it is Egica, under whom the Forum Iudicum took on its final shape, who is here being referred to. The significance of Vermudo's confirmation may well have been more political than judicial, and reflects the con- tinuing role of the Code and of the canon law collection as statements of principle and as restraints on royal arbitrariness. This is another dimension of the functions of the Forum Iudicum in this period that should not be overlooked.5

In conclusion it is necessary to consider briefly the subsequent I. MSS listed and described in Zeumer ed., Leges Visigothorum, pp. xix-xxv, but see Diaz

y Diaz, 'La Lex Visigothorum', for some revised datings and for fragments and MSS unknown to Zeumer. For bequests of copies of the Code see Cartulario de Celanova fos. 6r, I7V for Galicia, the references in C. Sanchez-Albornoz, 'Notas sobre los libros leidos en el reino de Le6n hace mil anlos' Cuadernos de Historia de Espana vol. i/ii (X944), pp. 222-38 for Le6n, and Zimmermann, art. cit. p. 267 for three eleventh century Catalan examples.

z. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional MS i8387 f. z4or for the bequest by Adosinda Gudesteiz, and fo. 39V for 'Gudesteus judex'; also included in the list of books was a 'liber canonum'.

3. Chronicon of Sampiro, ed. J. Perez de Urbel in Sampiro, su Cr6nicay la monarquia leonesa en el siglo X (Madrid, I 952), p. 344.

4. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional MS i8387 fo. zI4r; for historiography, see the Roda version of the Chronicle of Alfonso III: J. Prelog ed., Die Chronik Alfons III (Frankfurt, i980), p. I I.

5. For the genesis of the Code and its possible 'political' applications, see R. J. H. Collins, Early Medieval Spain (London, I 9 8 3), pp. I z 3 -8.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

5 10 SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

decline or modification of the importance of the Visigothic law. In the eleventh century its authority was tempered in Catalonia by the promulgation of the Usatges and in Castille-Le6n by the proliferation of the Fueros. The former remains, as it has been ever since it first became an object of study, a highly controversial text. It is quite conceivable that none of its clauses as they now stand have survived intact from the original version of c. io6o.1 Yet there seems to be little reason to doubt that the two principal complaints made in the Usatges against the Forum Iudicum to justify the promulgation of the new code represent some of the real difficulties that the latter presented in the mid-eleventh century. The objections were to the severity of the sentences as laid down in Lex Visigothorum, and to the difficulty of applying its rulings in a society with a more complex system of social stratification than had existed in the Visigothic kingdom.2 However, the Usatges in their original version were intended as a supplement to and not as a replacement of the Forum Iudicum, and many clauses of the new code were borrowed or adapted from the old. Furthermore, Count Ramon Berenguer cited the authority of Lex Visigothorum itself in the prologue to the Usatges to justify his own lawmaking.3 The role of Forum Iudicum in Catalonia should not be written off as early as it sometimes has been.4 Severity of sentencing - and here the Usatges had in view the high monetary value of the fines when translated into eleventh century equivalents - was obviously also a problem for the Leonese judicial system. Many of the early Fueros consist essentially of dispensations from and limitations of penalties that would be incurred if the Forum Iudicum were fully enforced. It should be borne in mind that the Catalans and Leonese of the tenth and eleventh centuries were as badly placed as we are today in respect of knowing what Visigothic sentencing was like in practice. How far the norms of the Code were modified in the actual working of the courts cannot be known, though it is worthy of note that some of the rebels of the late seventh century, such as those who had supported Paul against Wamba in 672, did not suffer in full the penalties that both the civil and the ecclesiastical laws laid down.5 In the Leonese

I. J. Ficker, Sobre los Usatges de Barcelonay sus afinidades con las 'Exceptiones Legum Romanorum' (Barcelona, i926); for a Latin text of the Usatges, see A. Helfferich, Entstehung und Geschichte

des Westgothenrechts (Berlin, i858), pp. 429-72 (but only based upon one MS), and for the vernacular version, see Usatges de Barcelona i Commemoracions de Pere Albert, ed. J. Rovira i Ermengol (Barcelona, I933).

2. Usatge lxviii, ed. Rovira i Ermengol, pp. 97-8.

3. 'Pr6lech', ed. Rovira i Ermengol, pp. 52-3.

4. The period c. I50- I I 50 is marked by the intensive and sophisticated use of the Forum Iudicum in the Catalan courts, as is well illustrated by Zimmermann, art. cit. For the eventual decline, see Iglesia Ferreir6s, art. cit. pp. 25 3-283, and for the older view that would minimize the role of L. V. after the promulgation of the Usatges, see Rovira i Ermengol, Usatges, pp.

7-I 5. 5. E. A. Thompson, The Goths in Spain (Oxford, I969), pp. 233-4.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i985 LAW AND CHARTERS IN LEON AND CATALONIA 511

kingdom it is clear that judges did not always apply the law in all of its rigour. Thus a Galician priest, who forced his mistress to have an abortion, was by the exercise of misericordia on the part of the bishop and judges merely deprived of his property and confined to a monastery instead of having to face execution.1 It is a mistake to think that the practice of justice under the rules of the Forum Iudicum could not be flexible, either in the seventh or in the tenth centuries.

A belief that in this as in other respects Castille was somehow different, and that its legal practices depended upon custom, possibly of 'Germanic' origin, rather than upon the norms of the Forum Iudicum is both prevalent and largely mistaken.2 In general it rests upon the misdating of some of the earliest sets of Fueros, and the acceptance of the genuineness of others that are either forged or interpolated.3 It may be thought to stem from the predominance of a school of historical interpretation that is prone to be uncritical in its Castilian nationalism. The whole of the history of the County of Castille in the ninth to eleventh centuries requires re-examination and a stiff dose of demythologizing. Although the evidence from the region is more limited in respect of the survival of judicial documents than is the case with Galicia and Le6n, the indications are strong that the Forum Iudicum was applied in the County in the tenth century as effectively as in the rest of the kingdom.4 Modifi- cation, when it came, was, as in Catalonia, a product of the mid- eleventh century at the earliest.

Although this brief and limited survey has had to concentrate on one particular section of the available evidence, it may be hoped that enough has been said to illustrate something of the way in which the complex legal heritage of Visigothic Spain was both preserved and applied in the Catalan counties and in the Kingdom of Le6n in the ninth and tenth centuries. Many difficulties obviously remain, and not all questions can be answered. The eighth century, the period of transition from the Visigothic monarchy to its northern Iberian Christian successor states, is untouched, though not neces-

I. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional MS i8387 fo. 246r, a document from Lugo. 2. Marquez-Sterling, Fernan GonZale., pp. 33-36, who finds it strange that some historians

are 'critical' of trusting the twelfth century Chronicle of Najera as an objective account of tenth century events.

3. e.g. the 'Fueros of Lara' of 922 or 93i, accepted by V. de la Cruz, Ferndn Gon!dle! (Burgos, I972), pp. 42-3, Marquez-Sterling, op. cit. p. 53, and others, but whose lack of authenticity is now firmly demonstrated in G. Martinez Diez, Fueros locales en el territorio de la Provincia de Burgos (Burgos, i98z), p. zX; for tenth century Castilian charters of immunity modifying the application of the law, see Martinez Diez, ibid. pp. I I-I4.

4. As is indicated by the surviving records: Becerro gdtico de Cardenia, ed. Serrano, docs xcviii, ccx, cclxxv, pp. I 13, 224-5, 292-3, Cartulario de ArlanZa, ed. Serrano, doc. xviii, pp. 48-9, and from a related area of the Rioja, Cartulario de San Millan de la Cogolla, ed. A. Ubieto Arteta (Valencia, I976), docs. xxiii and xxviii, pp. 40, 43-4. There were certainly procedural modifications and more limited notarial competence due to the local circumstances of this frontier area, but in the use of the Forum Iudicum and in the concern with documentation Castille is no different from the rest of the Leonese kingdom.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 06:23:23 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

5 12 'SICUT LEX GOTHORUM CONTINET': July

sarily untouchable; and of course the rise of the law of the Fueros and the restriction and modification of the role of the Forum Iudicum in the eleventh century demand fuller treatment than it has been possible to offer here. It may be thought that what has been considered sheds light on how the Visigothic legal system might have functioned in its hey-day in the Visigothic Kingdom proper, as well as on how in its procedures, its concern for documentation and in the quality of its justice, it continued to flourish in the Christian states after the Arab conquest. One might ask in conclusion whether anything better could be found anywhere else in Europe in the earlier Middle Ages?

ROGER COLLINS