Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b …schwert.ssb.rochester.edu/short0110.pdfShort...

Transcript of Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b …schwert.ssb.rochester.edu/short0110.pdfShort...

© Robert C. Apfel, John E. Parsons, G. William Schwert, and Geoffrey S. Stewart, 2001.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Actions Robert C. Apfel Bondholder Communications Group, New York, NY 10004

John E. Parsons Charles River Associates, Boston, MA 02116

G. William Schwert University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14627 and National Bureau of Economic Research Geoffrey S. Stewart Jones Day Reavis & Pogue, Washington, DC 20004

First Draft: July 2001

In a short sale, an investor sells a share of stock he does not own and profits when the price of the stock declines. A peculiar feature of short sales is the apparent increase in the number of shares of stock beneficially held by investors over and above the actual number of shares issued by the corporation. It has previously been noted that this may create problems in the execution of proxy votes. In this paper we illustrate a related problem in the prosecution of claims of securities fraud. We examine this problem using the recent case of Computer Learning Centers, Inc., (CLC) in which the number of short sales was extremely large.

Plaintiffs in the Computer Learning Centers case proposed a class including all those who purchased CLC common stock from April 30, 1997 to April 6, 1998. Defendants opposed certification of the class, focusing on the large number of short sales and the resulting difficulty in establishing which members of the class actually had standing to sue. The court denied the motion for class certification. Although the court gave plaintiffs leave to amend the class, the case was settled before a new class was identified. Key words: Short-selling, Litigation, Securities fraud JEL Classifications: G14, G18, K22

Corresponding authors: John E. Parsons, Charles River Associates, and G. William Schwert, William E. Simon Graduate School of Business Administration, University of Rochester. Email: [email protected]

*The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

1

1. Introduction

In a short sale, an investor sells a share of stock he does not own, and only later purchases

a share to close out the transaction. The short seller profits when the price of the stock declines.

A peculiar feature of short sales is the apparent increase in the number of shares of stock

beneficially held by investors over and above the actual number of shares issued by the

corporation. It has previously been noted that this may create problems in the execution of proxy

votes.1 In this paper we illustrate a related problem in the prosecution of claims of securities

fraud. We examine this problem using the recent case of Computer Learning Centers, Inc.,

(CLC) in which the unusually large number of short sales factored significantly into the case.

See Ganesh, L.L.C. v. Computer Learning Centers, Inc., 183 F.R.D. 487 (E.D. Va. 1998).

Plaintiffs in the Computer Learning Centers case proposed a class including all those who

purchased CLC common stock from April 30, 1997 to April 6, 1998, with some exceptions.

Defendants opposed certification of the class, focusing on the large number of short sales and the

resulting difficulty in establishing which members of the class actually had standing to sue. The

court denied the motion for class certification. Focusing on the fact that the fraud on the market

presumption of reliance does not apply to short sellers, the court found that individual issues in

regard to proof of reliance would overwhelm common questions of law or fact. The court gave

plaintiffs leave to amend the class, but the case was settled before a new class was identified.

The case raised a number of interesting legal questions surrounding short sales that did not get

addressed prior to settlement.

1 Short-Selling Activity in the Stock Market: Market Effects and the Need for Regulation, Part I, Report of the Committee on Government Operation, U.S. House of Representatives, December 6, 1991, pp. 24-35.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

2

2. The Computer Learning Centers Case

Computer Learning Centers, Inc., provided education and training in computers and

information technology. Its adult students obtained associate and non-degree diplomas in pursuit

of entry-level jobs. Students were expected to complete their programs in 8 to 16 months for full-

time students and 16 to 32 months for part-time students. CLC also provided shorter continuing

education and training programs. As of January 31, 1998, shortly before the class action suit was

filed, CLC enrolled about 12,000 new students annually at its 25 locations. At that time, tuition

ranged from $6,100 to $16,500 for diploma programs and from $15,210 to $21,995 for associate

degree programs. The majority of CLC’s students participated in some federally supported

student financial aid program, and in 1998 approximately 73% of the company’s revenues were

funded from Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965.2

CLC was incorporated in 1987. In 1995 it made an initial public offering and its started

trading on the NASDAQ. At the start of 1998 there were 16.2 million shares outstanding. Of

these, either officers or directors of CLC owned about 5 million shares. Institutional investors

owned another 6.1 million shares. Only about 5 million shares were available for active trading.

On March 10, 1998 news stories appeared describing a complaint filed by the Attorney

General of Illinois in the Circuit Court of Cook County, which asserted that CLC had defrauded

students at its Schaumberg, Illinois Learning Center.3 This precipitated a nearly 50% drop in the

price of CLC stock in the two days following the announcement, from $36.875 on March 9 to

2 Computer Learning Centers, Inc., 10K, Fiscal year ended January 31, 1998. 3 The suit alleged violation of Illinois Private Business and Vocational Schools Act and the Illinois Consumer Fraud and Deceptive Business Practices Act.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

3

$19.734 on March 11. The next day the company announced financial results for fiscal year end

1998 and the stock fell further to $18.625.

On March 13, 1998 a class action lawsuit was filed against CLC in the US District Court

for the Central District of California on behalf of all purchasers of CLC Common Stock from

April 30, 1997 through March 10, 1998. Eight other similar cases were filed in subsequent

months. All of the suits were consolidated and transferred to the US District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia. The complaints alleged violations of the Securities Exchange Act of

1934. They claimed that CLC was admitting a large number of unqualified students in order to

increase revenue, providing a substandard education, and covering up these actions by providing

misleading statistics regarding the quality of students, the success rate of job placement and

salaries, the quality of faculty and equipment. The complaints also alleged that CLC insiders

profited by selling their shares of CLC stock while in possession of materially adverse

information.

On April 6 CLC disclosed that the Illinois State Board of Education had entered a

preliminary administrative order limiting CLC’s ability to enroll new students at the Schaumberg

center. CLC was also notified by the U.S. Department of Education that it had placed all of the

company's schools on what DOE describes as “heightened cash monitoring status.” The next day

the stock fell another 26% from $17.625 to $13.00. When the various class action suits were

consolidated, the class period was extended through April 6, 1998.4

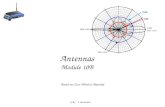

Figure 1 shows a graph of CLC’s stock price with the proposed class period marked. The

events prompting the suit clearly mark a sharp drop from the peak price. A subsequent run-up in

4 Plaintiffs’ Consolidated Amended Class Action Complaint, US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Alexandria Division, Ganesh, L.L.C., et al. v. Computer Learning Centers, Inc., et al., Case No. 98-859-A, August 7, 1998.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

4

the price and second sharp drop are also in part tied to ongoing legal difficulties. On May 5

CLC’s stock price climbed 27% to $14.625 on rumors that the Illinois State Board of

Education’s suspension was to be lifted. The next day there was word that the United States

Department of Education was inquiring after details of the company’s participation in the Title

IV program and the stock fell again by 8%. The following day, May 7, official announcement of

the Illinois State Board’s action started the stock climbing again by 21% to $16.25. On June 8

the Illinois Attorney General announced a settlement with CLC. The stock price leapt again by

28% from $17.75 to $22.6875. The stock continued to climb and reached its peak of $30 per

share on July 14, 1998. Between July 14 and August 10 the stock drifted generally downwards.

On August 11 the price dropped 25% from $22.625 to $16.875 on news of a new lawsuit

alleging that the company had discarded student-related files sought by federal auditors. The

stock continued drifting generally downwards until August 28 and 29 when it fell a precipitous

64% from $13.375 to $4.75 after the company announced weak second quarter earnings results

related to its legal difficulties and low enrollment. Following the second collapse the stock price

performance has been poor and in January 2001 the company filed for bankruptcy to liquidate its

assets.

One of the unique features of the Computer Learning Centers case is the volume of short

sales during the period leading up to the large price movements. Figure 2 shows the size of the

outstanding short interest in CLC stock as a percent of shares outstanding. By April, the 6

million shares sold short exceeded the 5.1 million shares in CLC’s float, the number of shares

available for active trading. For the typical firm on the New York Stock Exchange and the

American Stock Exchange short sales outstanding are less than 2% of actual shares outstanding.

Short sales outstanding climb to 7% of actual shares outstanding for fewer than 5% of the firms,

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

5

and to 13% of actual shares outstanding for fewer than 1% of the firms.5 Short interest for

Computer Learning Centers was a markedly greater fraction of shares outstanding—25% on

February 13, 1998, 26% on March 13, 1998 and 37% on April 15, 1998.

3. Short Sales

3.1. Short Selling Mechanics

The typical investor purchases a stock hoping the price will rise so that he can then sell it

at a profit. A short seller takes the opposite position, first selling a stock hoping that the price

will fall. The short seller will then be able to purchase the stock at this lower price and close out

of the transaction with a profit.

Conceptually the simplest way to implement a short sale is something like a forward

contract: a short sale is a sale at a price fixed now for delivery later.6 Another relatively simple

way to implement a short sale is to take advantage of the window of time allowed for the actual

delivery of shares on a sale. A seller of stock has three days to make delivery of the stock sold. A

short seller can execute a sale if he is able to obtain a share for delivery within this window of

time. A short sale made without possession of an actual share is called a naked short.

In practice, short selling is more commonly facilitated through an accompanying

borrowing transaction. The short seller enters into an agreement to borrow a share from one

investor in order to sell it to another investor. The short seller hopes to be able to purchase a

share at a later date and at a lower price. He can then return this share to the investor from whom

5 Paul Asquith and Lisa Meulbroek, “An empirical investigation of short interest,” Harvard Business School Working Paper 96-012, Table 1, results for 1993, the most recent date for which they present data. The data show that mean short interest has been increasing over time. 6 This is how Judge Posner characterizes a short sale in Sullivan & Long v. Scattered, 47 F.3d 857, 858.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

6

he had originally borrowed one. The short seller’s profit is the difference between the initially

high selling price and the later low buying price, less the costs of borrowing the stock in the

interim.

When borrowing a share, the short seller agrees to return a like kind and amount of stock

within a specified period of time, and also posts collateral as security for the loaned stock. The

lender of the stock earns a profit by charging a fee for the loan and by investing the collateral

less a rebate on such earnings paid to the borrower. The lender continues to expect to enjoy the

gains from any increase in the price of the stock (and suffers the loss from any decrease) since

she will receive the share back at the end of the loan period and can then sell it at the higher (or

lower) price. The borrower also typically agrees to make the lender whole for any cash

distributions made on the stock during the period of the loan.

3.2. The Apparent Expansion of Beneficial Ownership Due to Short Sales

Figures 3A, 3B and 3C show the steps in a short sale transaction. Figure 3A shows the

situation before a short sale. Persons J and K each own one share of stock issued by Company X.

They are the two shareholders of record. Figure 3B shows the execution of a short sale. Short

Seller S borrows a share from person K and sells this share to Person L. Although we say that the

share is borrowed, since the borrowed share is then sold to a third party, we must be careful

about what we mean by borrowed. Two persons, the one who lent it to the short seller and the

one who bought it from the short seller, cannot own the same share simultaneously. For the

moment, let us say that person L becomes the true owner of record while person K is not an

owner of record, at least not while her share is lent out. Later we will describe the institutional

features of actual short sales and discuss what is known about who is an actual owner of record.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

7

Figure 3C shows the situation immediately after the execution of a short sale. There are

still two shares outstanding that were issued by Company X. Persons J and L are now the

shareholders of record for these two shares. While person K is no longer a shareholder of record,

she has a beneficial interest in a share of stock, an interest that has been created by the short

seller’s promise to return a share and to make-up for any cash distributions paid by the company

in the interim. In this sense, we say that person K owns an ‘artificial’ share created by the short

seller.

To illustrate the short seller’s role in creating an artificial share it is convenient to review

what happens in the event that Company X makes a dividend payment while the short sale is in

place. The company only makes a dividend payment on two shares—to its shareholders of

record, persons J and L. However, three persons—J, K and L—believe themselves to be

beneficial owners of a share and expect to enjoy the benefit of any cash distributions made by the

company. It is the short seller who makes the third dividend payment, the one to person K.

In this sense the short sale has resulted in an apparent expansion of the beneficial

ownership of the company’s shares. Where previously investors had held beneficial ownership in

only two shares of the company’s stock, now investors hold beneficial ownership in three shares.

This expansion is only apparent, however, as it must be. The short seller who issues a sort of

‘artificial’ share creates the apparent expansion in the beneficial ownership. He takes the

mirrored position, paying a dividend when the corporation pays a dividend, enjoying a loss when

the third shareholder enjoys a gain and vice-versa. After netting out the short seller, the total

beneficial ownership matches the number of shares actually issued by the firm. There is an

expansion of beneficial ownership when the short seller himself has been left out of the equation,

but taking the short seller’s offsetting position into account there is no expansion. Table 1 below

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

8

shows the situation. Three investors have long positions in the company’s stock. One investor

has a short position. The net position is 2 longs.

Table 1

Illustration of the expansion of beneficial share ownership due to short sales

Investor Long Positions Short Positions Net Positions

J 1 0 1 K 1 0 1 L 1 0 1 S 0 1 -1 Total 3 1 2

The fact that the expansion of the number of shares is only apparent and not real

manifests itself in the matter of shareholder votes. This is one characteristic of an actual share of

stock that the short seller cannot reproduce. In the event of a shareholder vote, only as many

shares as were issued by the company can be voted. In our example that is, two shares. The

shareholders of record will vote these. The artificial share created by the short seller cannot be

voted. These artificial shares are therefore not truly identical with the actual shares issued by the

company.

3.3. Short Selling and Damages in 10b-5 Actions

In the case of a 10b-5 action, this apparent expansion of the beneficial ownership has real

consequences. It multiplies the number of investors that are potential claimants in a suit and

correspondingly multiplies the potential damages. In many cases, where the number of short

sales is relatively small, this effect may not be very great. In the Computer Learning Centers case

where the number of short sales was extraordinarily large, the effect was significant. Damages

asserted by holders of artificial shares created by short sellers increase by nearly 50% the total

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

9

estimated damages. Defendants in the case asserted that holders of artificial shares had no

standing and that therefore the company was not liable for these damages.

The extra damages arising from short sales can be illustrated using the simple example

given above. Suppose that both investors J and K had purchased their shares at the price of $10.

Suppose as well that the short seller originally sold a share to person L at the same price of $10.

Furthermore, let us suppose that $10 is an inflated price given information that the company’s

management has not revealed. On revelation of this information, the price falls to $7. The short

seller is now able to purchase a share at $7 and close out his short position, returning a devalued

share to person K. Investors J and L, the two shareholders of record, each suffer a loss of $3.

Investor K, the holder of the artificial share has also lost $3, while the short seller has gained the

same $3. Damages calculated on trades in the company’s actual shares are $6, while damages

calculated on trades including the artificial share created by the short seller, are $9 or 50% more.

In the sections that follow we present illustrative damage calculations for the Computer

Learning Centers case, with and without the artificial shares created by short sales.

3.3.1. Price Inflation, Affected Shares and Damages

The first step in calculating damages in a 10b-5 matter is determining the inflation—the

amount by which the alleged fraud has pushed the price of the stock above its true value. Figure

4 shows a graph of a hypothetical price inflation that plaintiff might have alleged in the

Computer Learning Centers case. The premise underlying the calculation is that the share prices

at the start and at the end of the class period reflect the true value of the stock. The price of a

share of stock in Computer Learning Centers, adjusted for stock splits, was $13.31 on April 30,

1997, the start of the class period, and $13.00 on April 7, 1998, the close of the class period. For

simplicity in the hypothetical calculation we set the true value of a share of stock in Computer

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

10

Learning Centers at $13 throughout the class period. The price inflation during the class period is

simply the difference between the actual price on any given day and the true value. In the

hypothetical example the inflation climbs above $25 per share by February 2, 1998, is still above

$23 per share on March 9, 1998, and then falls precipitously below $10 per share until April 7,

1998 when all of the inflation is gone.7

An investor who purchases a share while the stock price is inflated is damaged by the

difference between the amount of the inflation at the times it purchased and sold the share.

Assuming that the investor holds the share until the inflation is entirely eliminated, the investor is

damaged by the amount of the original inflation. If the investor sold the share while the price was

still inflated, he may or may not be damaged depending upon whether the inflation increased or

decreased during the time he held the share. If the inflation at the time of the sale is greater than

the inflation at the time of purchase, then the investor is not damaged. But if the inflation at the

time of the sale is less than the inflation at the time of purchase, then the investor is damaged by

the decrease in the inflation. If an investor had owned a share before the stock price became

inflated and held it throughout the period of inflation, then the investor is not damaged,

regardless of whether the later price is above or below the initial price. When an investor is

damaged on a purchase of shares, the shares are called ‘affected shares’. Shares held by investors

that do not incur damages are called ‘unaffected shares’.

With the inflation in hand and with each investor’s record of purchases and sales, it is

straightforward to determine the total damages in a securities fraud case. Unfortunately, in most

securities fraud cases it is necessary to estimate damages before much detailed information is

7 The Computer Learning Centers case settled before specific price inflation was alleged. The inflation shown here is used purely for illustration and is therefore very simply constructed. A proper model of the price inflation would be based on a detailed analysis of the facts of the case. It would also incorporate information about general stock market movements and the performance of comparable companies over the class period.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

11

available regarding individual purchases and sales of shares. Information about the total number

of purchases on each day is available, but it is not possible to match the purchases made on a

given day with sales made on a later date. Therefore the second step in calculating damages is

estimating the number of affected shares.

Estimating the affected shares begins with an estimate of the number of shares available

for active trading during the period when the price is inflated. This is called the float. The

starting point for calculating the float is the number of shares outstanding. Next, any shares

known to have been held throughout the entire class period are subtracted since these holdings

were not available for active trading during the period. Typically the only holdings for which

information is available are those owned by insider and institutional investors that are required to

file with the SEC. The solid line in Figure 5 graphs the float throughout the class period for the

Computer Learning Centers case. On April 30, 1997, at the start of the class period, the number

of shares outstanding was 15.7 million and the number of shares held by insiders was 5.6

million.8 The number of shares held by institutions throughout the class period was 6.1 million,

and therefore the float was 3.9 million shares on April 30, 1997. By March 11, 1998 the number

of shares outstanding was 16.2 million, and the number of shares held by insiders was 5.0

million. Therefore the float was 5.1 million on March 11, 1998. The float was 5.1 million shares

on April 7, 1998, the close of the class period.

The next step is to take the shares actively traded and determine a profile of the affected

shares: which shares were bought and sold at which prices and therefore how many are affected

by the inflation. Public data on the volume of shares bought and sold each day is the starting

point for this calculation. These public data on total transactions are combined with an

8 Figures for dates prior to January 9, 1998 have been adjusted to account for a 2-for-1 stock split.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

12

assumption about which shareholders have sold their shares on a given day. One assumption is

that all shareholders are equally likely to sell their shares on any given day. This is the premise

of the Proportional Trading Model. An alternative assumption is that some shareholders are more

likely to hold their positions for a longer period of time, while other shareholders are more likely

to hold their positions for a shorter period of time. This is the premise of the Accelerated Trading

Model and the Multiple Trader Model. A trading model generates a profile of which

shareholders traded on which day and therefore which shares are affected.9 The solid line in

Figure 6 shows a graph of the estimated affected shares using the Proportional Trading Model.

The affected shares reached 5.1 million shares by March 11, 1998.

Once a profile of affected shares has been estimated, this is combined with the estimated

price inflation to yield an estimate of damages for this hypothetical example. The solid line in

Figure 7 shows a graph of the cumulative damages on shares purchased through any given date.

Estimated damages using the hypothetical price inflation reached nearly $126 million.

3.3.2. The Impact of Short Sales on the Estimate of Affected Shares and of Damages

As noted earlier, short sales increase the total number of shares outstanding in the market

by adding artificial shares to the actual shares issued by the company. Because short sales were

so significant in the Computer Learning Centers case, the effect on damages is likely to be

greater than in the typical securities fraud case. One can gain a fair estimate of the likely impact

using the hypothetical inflation described earlier together with the calculation of affected shares.

This is done by simply changing the assumption about whether the artificial shares created by

9 There is significant dispute about the validity of any of these models in estimating the true pattern of purchases and sales. The effect of short sales on the calculation is similar for any of these models, and therefore we illustrate results using the simplest one, the Proportional Trading Model. If one has access to actual trading records, it is not necessary to use any of these models.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

13

short sellers are to be included in the calculation of shares available for active trading. The

difference between the total damages calculated using both actual and artificial shares and the

total damages calculated earlier using only actual shares is an estimate of the impact short sales

have on damages in the Computer Learning Centers case.

The dashed line in Figure 5 is the float for Computer Learning Centers shares calculated

including short sales. This is calculated by taking the total number of shares outstanding, adding

the outstanding short interest, and then subtracting shares held by insiders and shares held by

institutional investors throughout the class period. On April 30, 1997, at the start of the class

period, the number of shares outstanding was 15.7 million, the short interest outstanding was 0.1

million shares, and the number of shares held by insiders was 5.6 million. Subtracting the

number of shares held by institutions throughout the class period, the float with short sales was

4.1 million shares on April 30, 1997. By March 11, 1998 the number of shares outstanding was

16.2 million, the short interest outstanding was 4.2 million, and the number of shares held by

insiders was 5.0 million. Subtracting the number of shares held by institutions throughout the

class period, the float with short sales was 9.4 million on March 11, 1998. The float with short

sales was 10.4 million shares by April 7, 1998 after the close of the class period. The majority of

the increase in the float with short sales over the class period is due to an increase in the

outstanding short interest. The short interest in Computer Learning Centers shares went from 0.1

million shares on April 30, 1997 up to 5.3 million shares by April 7, 1998.

The dashed line in Figure 6 is the number of affected shares calculated including short

sales. The affected shares including short sales reached 8.6 million shares by March 11, 1998 and

9.6 million shares by April 7, 1998. Short sales raise the total affected shares by 3.5 million

shares by March 11, 1998 and 4.5 million shares by April 7, 1998.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

14

The dashed line in Figure 7 shows the damages calculated including short sales. The final

damages at the end of the class period calculated including short sales are nearly $187 million or

48% more than the $126 million in damages calculated excluding short sales.

The effect of the substantial number of short sales in Computer Learning Centers stock

during the class period is to overstate the damages associated with the actual shares issued by

Computer Learning Centers. Using the higher damage numbers, Computer Learning Centers

would be subjected to paying damages on shares that were effectively issued by the short sellers.

3.4. The Mystery of Who is the Owner and Who the Lender

In our earlier example we described short seller S as borrowing a share of stock from

investor K and selling it to investor L. We noted that the term ‘borrowed’ was problematic since

it implies that investor K continues to own the share which has simultaneously been sold to

investor L. In fact, the borrowing transaction is more like a sale from investor K to short seller S,

combined with a forward sale in which S promises to return the share to K at the same price plus

interest and dividends, if any. Conceived this way, it is clear that investor K has temporarily

surrendered ownership and there is no complication created by two investors simultaneously

owning the same share.

3.4.1. Institutional Changes in Custody Practices

Before 1973, almost all settlements of stock transactions were made by delivery of

physical stock certificates. A “stock power” on the back of the certificate would be endorsed in

favor of the purchaser. Short sellers typically had to obtain physical certificates to borrow from

lenders. Lenders with physical certificates registered in their names had to endorse their stock

over to the borrower. This was in accordance with Article 8 of the Uniform Commercial Code.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

15

In the standard Securities Loan Agreements published by the Security Industry

Association as well as the standard customer agreements between brokerages and their

customers, the parties agree that the lending customer waives his right to vote proxies for any

securities that have been lent. The reason for this waiver of the right to vote is operationally

critical to the stock loan transaction. On the record date for the proxy or annual shareholders

meeting, only the “stock holder of record” is entitled to vote. Among our hypothetical customers,

‘K’ and ‘L’, only L, the purchaser of the lent shares (who bought her shares from the short) is

entitled to vote at the meeting. If the lender of the shares, K, had them out on loan on the record

date, she is not entitled to vote.

In these circumstances it would have been clear that investor K owned the artificial share

while investor L owned the actual share. In lending her share, investor K surrendered ownership

in the actual share and substituted ownership in the artificial share.

Circumstances changed significantly starting in 1973 because of the adoption of the

practice of holding securities in nominee name (“street name”) through intermediaries including

brokers, banks and securities depositories. The move to holding securities in street name was part

of a wider shift that followed on the securities industry’s paperwork crisis in the late 1960’s,

when processing problems associated with the physical certificated transfer of millions of

securities caused a major disruption in the financial industry. The Depository Trust Company

(DTC) was created in 1973 as a privately operated ‘Federal Reserve for stocks’ designed to

provide efficient, secure and accurate central custody and post trade processing services for

transactions in the United States securities markets. The DTC is owned by several hundred

brokerage firms, financial institutions (collectively, the DTC “participants”), and the New York

and American Stock Exchanges. Its vaults in New York contain over $23 trillion of securities,

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

16

including stocks, corporate bonds, mutual funds, warrants, and municipal bonds and government

obligations.

The DTC carries out two major functions. The first is the immobilization of the securities

of DTC participants, which reduces the need for participants to maintain their own certificate

safekeeping facilities. Second, the DTC maintains a computerized book-entry system in which

changes of ownership among participants are recorded. This replaces costly, problem-prone

physical delivery of securities for settlement.

The DTC holds all securities in “fungible status” (also known as “fungible bulk”), with

the DTC’s computers recording ownership of aggregate amounts of each security in the name of

a participant firm. The DTC does not maintain records describing the ownership of securities by

individual customers, other than for the holdings of major institutions that are themselves DTC

participants. Instead, the DTC regards the participant firms as the nominal holders, in “street

name”, of all their customers’ securities. Customer level record keeping is the responsibility of

the participant firms.

The DTC’s book entry system allows participants to deposit securities for safekeeping,

transfer them conveniently to other participants, collect payment for the securities transferred

and withdraw certificates, if desired by a customer. It is the widespread use of these services by

DTC participants that creates economies of scale, permitting low-cost processing and speed

without the sacrifice of security and accuracy. In 1999, for example, the DTC processed more

than 189 million computer book entry deliveries between brokers and clearing corporations, with

a value of over $94 trillion. Today over 72% of all common shares issued by NASDAQ-listed

companies are immobilized at the DTC, and not held by the investors themselves.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

17

Not all changes in security ownership result in DTC transfers. The National Securities

Clearing Corporation (NSCC) operates clearing, netting and settlement services that assist

member firms in processing transactions. The NSCC compares buy and sell transactions and nets

them down to reduce the number of transactions requiring a transfer of securities positions on the

books of DTC. For example, if, during the same day, customers of Merrill Lynch sell customers

of Goldman Sachs 50,000 shares of XYZ stock, and customers of Goldman Sachs sell customers

of Merrill Lynch 50,000 shares of XYZ stock in numerous separate transactions, the NSCC will

automatically net down the transactions, and no transfers will result on DTC books. In 1999,

DTC and NSCC combined together under a new umbrella organization called Depository Trust

and Clearing Corporation (DTCC).

Under the standard arrangements between customers and their brokerage and banking

firms, the securities held in brokerage accounts are commingled in a single fungible mass. For

example, if Merrill Lynch had five customers who held CLC stock on a single day, Merrill

Lynch would hold all of the shares of these five customers in a single commingled fungible bulk

account at DTC in Merrill Lynch’s name. Of course, Merrill would have a record of the identity

of the investors whose stock is represented in the mass. Consequently, where securities are held

in street name, the task of keeping records as to which individual customer owns how much of

which security is the responsibility of the brokerage firm. In the absence of paper shares, the only

written evidence that an individual customer has of his or her holdings are brokerage statements

or trade confirmation slips.

The typical brokerage customer margin account agreements allow the brokerage to

hypothecate or lend the customers’ securities without notice or benefit to the customer. It is the

brokerage that earns interest on the loan, and not the shareholder, and this fact is acknowledged

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

18

in the account agreement. When brokerage firms lend their customers’ stock, they do so out of

the general pool of marginable fungible securities held by the firm. Having deposited all of their

customers’ securities into a fungible mass, they cannot and do not keep records documenting the

ownership of the securities that have been lent. Brokers cannot tell their customers when their

stock has been lent (or returned) because it is the fungible pool of stock that serves as the source

of the loans. In fact, this pool of stock has no identifying characteristics linking it to particular

customers, because it is simply an electronic entry at the DTC and the brokerage.

The move to holding shares in street name significantly complicates identifying which

investor holds an actual share and which investor holds an artificial share. Figures 8A, 8B and

8C reproduce the short sale transaction previously shown in Figures 3A through 3C, with the

difference that shares may be owned through a broker and kept at a brokerage account. In Figure

8 investors J and K have bought their shares through the broker who holds them in street name.

The short seller borrows a share from the broker. In contrast to the example shown in Figure 3B,

in which investor K knows that its share had been lent, in the example shown in Figure 8B,

neither investor K nor J knows that one of their shares has been lent. Customers whose shares are

held in street name do not possess an actual stock certificate evidencing their ownership. The

only written evidence an individual customer has of his or her holdings are the records of the

brokerage, including statements or trade confirmation slips.

3.4.2. Short Sales and Proxy Votes

This problem manifests itself in the execution of proxy votes. On the record date for the

annual meeting, the company identifies the names of the holders of its stock. Typically the

largest such holder is “CEDE & Co.,” the nominee name of the DTC. The company requests

from the DTC a list of the participants for whom the DTC is holding the shares on the record

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

19

date. It also obtains from the DTC an Omnibus Proxy in which the DTC transfers its rights to

vote to each of its participants in accordance with the amount of stock held by each such firm on

the record date. With respect to securities that have been lent from one DTC participant to

another, DTC’s Omnibus Proxy shows the securities as being held by the DTC participant that

purchased the shares from the short seller. Nothing in the DTC’s Omnibus Proxy identifies the

shares as having been loaned or identifies the parties to the stock loan transaction.

Each DTC participant firm listed on the DTC Omnibus Proxy asks each beneficial owner

of stock to give the firm direction on how to vote on their behalf. Shares are to be voted

according to these instructions and in the case of contested issues are not to be voted in the

absence of instruction. However, when the broker has lent shares, the number of shares owned

beneficially exceeds the number of shares owned as a matter of record, and it is possible for

investors to collectively return proxy instructions for more shares than the broker controls. Since

it is impossible to determine who has—and who does not have—the right to direct the participant

firm to vote the shares, many shares are never voted, or are voted only partially, using a pro rata

allocation formula generated by the brokerage firm itself. There is little information about how

often this happens. In response to an inquiry from a Congressional subcommittee, the New York

Stock Exchange referred to the “rare instance that such a situation occurs,” although the

Congressional report suggested it may not be rare.10 Even when the broker receives instructions

for fewer shares than it controls, in voting the shares it is effectively allocating the voting rights

to those shareholders who gave specific instructions as against those shareholders who gave no

instructions.

10 Short-Selling Activity in the Stock Market: Market Effects and the Need for Regulation, Part I, Report of the Committee on Government Operation, U.S. House of Representatives, December 6, 1991, p. 29, fn. 24 and pp. 29-31.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

20

The November 1998 proxy battle for control of Integrated Circuit Systems, Inc., a

Pennsylvania semi-conductor firm, illustrates the problems created by short selling in the context

of proxy contests. Dr. Stavro Prodromou, the former chairman of the firm, proposed an

opposition slate of directors. Prodromou was trying to take back control of the company from the

directors who had ousted him less than two years earlier. Only about 15% of the outstanding

shares were registered in the names of individuals or corporations holding share certificates. The

remaining 85% of the shares were registered in the name of The Depository Trust Company

(“DTC”). That is, they were held in “street name.” DTC held these shares for the benefit of its

participants, the major “street name” firms such as Smith Barney and Prudential. These

brokerage firms, in turn, held the shares in the brokerage accounts maintained for their

customers.

The “registered certificated” holders were entitled to vote by virtue by of their inclusion

in the list of shareholders maintained by the registrar. All but one of these holders received

Prodromou’s solicitation materials directly and were invited to return their votes directly to the

vote tabulator. The large “registered certificated” holder who did not, and does not as a matter of

policy, return a vote was DTC. Instead, DTC executed an “omnibus proxy,” a document that

assigns the depository’s right to vote to the banks and brokers who held their customers’ stock

through DTC. Each such broker was assigned voting rights equal to the number of shares on

deposit with DTC on the record date. The DTC participant firms, in turn, were required by SEC

rule to forward proxy material to the customers for whom they hold stock and to seek

instructions from such customers – the beneficial owners of the shares – on how to vote such

customer shares.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

21

To initiate the shipping of Prodromou’s shareowner solicitation material to “street name”

customers, each DTC participant firm was asked for a report on the number of sets of materials

they would require to reach each of their customers – and how many shares all of such customers

held. It was at this time that the existence of a short sale/stock lending/ownership imbalance

situation was identified. Several of the “street name” firms requested copies of Prodromou’s

solicitation materials for customers whose aggregate holdings totaled more shares than existed in

their accounts at DTC. This meant that brokers could have received voting instructions from

their customers for more shares than the broker was entitled to vote by DTC’s “omnibus proxy”

assignment. Table 2 shows the brokers and banks that mailed ICS proxy materials to customers

in excess of the firms’ holdings at the DTC.

It is believed that these firms had lent a portion of their customers’ stock, thus reducing

the number of shares held at DTC below the level “owned” by their customers. SEC and SRO

rules provide that brokerage firms and bank nominees are to send to their customers proxy

instruction forms requesting their customers’ positions only with respect to the amount of

securities for which such customers have a right to vote. And, such rules provide that votes

presented on the behalf of their customers must be for customers who actually own the securities

and have a right to vote. Rather than disenfranchise some of their customers from voting, the

firms followed what we understand to be industry practice – mailing copies of the materials to all

of their customers who had deposited ICS shares, obviously hoping that fewer customers would

return ballots than those originally solicited. Brokers explained that in regularly scheduled

annual meeting proxy votes, they generally try to “undo” securities loans before proxy record

dates – thus providing them with sufficient quantities of stock at DTC. However, in Prodromou’s

contest the meeting was moved so there was not enough warning in advance of the record date to

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

22

accomplish this unwinding. In this case some of the firms actually over voted their record date

position.

The voting in the ICS meeting was contested on the grounds that many of the votes were

cast in violation of Regulation A under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the rules of the

NYSE. However, the Judges of Election of the Connecticut Corporation System affirmed the

results.

4. Standing and Class Certification Issues

The practice of short selling raises questions about the relationship of three distinct sets

of investors in a 10b-5 matter. There are questions about the short sellers themselves. Does a

short seller have standing? Can he properly be included in the class? There are also questions

about those investors who have lent their shares to a short seller and maintain their beneficial

interest through their agreement with the short seller. Does the holder of an ‘artificial’ share have

standing? Is it proper to certify a class that may include these investors? Finally, what about

those who purchase the stock from the short seller? Are these shareholders the only investors

who may participate in a plaintiff shareholder class?

4.1. “Real” and “Artificial” Shares

As pointed out above, the act of shorting a share of stock creates an artificial share.

These artificial shares are called “shares”, but they are not. They are not stock that is issued by

the company; they are not authorized for issuance by the company’s Board of Directors. In fact,

in some cases the sum of these artificial shares and the real shares exceeds the number of shares

the company even is authorized to issue. The shares are not registered with (or approved for sale

by) the Securities & Exchange Commission, and the company neither sells, nor receives value

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

23

for, them. See Committee on Government Operations Report, 3-5, 24. Similarly, these are not

shares of stock that have an entitlement to dividends or distributions from the company and, to

the extent they even have a right to vote, it is pursuant to the contract between the short seller

and the brokerage firms that loaned the stock, not because they are actually “shares” of a

company’s stock. The artificial nature of these shares is even more telling in the case of “naked”

short sales, that is, where a short seller sells stock without first borrowing it.

One of the perplexing questions about short sale transactions is the issue of who truly

“owns” the share that is loaned. The question is a difficult one because, according to the

standard industry Master Securities Loan Agreement, both the lender of the share and the short

seller each have some rights that fall within the rubric of “ownership”. For example, the SIA's

Master Securities Loan Agreement stipulates that the short seller will enjoy “all of the incidents

of ownership,” including the right to transfer title to the share. On the other hand, the lender of

the share retains the right to dividends and, it seems, the right to vote the share when the shares

are held through a broker and the DTC in a fungible mass.

Under the federal securities laws, the fact that the short seller has the right to transfer title

to the share indicates that he is the “owner”. “A person shall be deemed to own a security if (1)

he or his agent has the title to it….” 17 C.F.R. § 240.3b-3 (1998). This conclusion is supported

by other evidence, notably the fact that a person who buys that share from the short seller is,

under the securities laws, considered the share’s new owner. Id., § 240.3b.3(2). But if this is

true, then the “share” that still appears on the customer account statement of the brokerage firm

as belonging to the lender of the share must be the “artificial” share.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

24

4.2 “Are Artificial Shares “Securities”?

This, in turn, leads to the questions whether that “artificial” share is itself some form of a

“security” within the meaning of the federal securities laws and whether that “artificial” share is

a security upon which a lawsuit can be brought. Although there is room for debate, the more

persuasive view is that the “artificial” share is not a security. As noted before, the “artificial”

share is not even a “share” to begin with: it simply is called a “share” because of the

bookkeeping conventions of brokerage houses. In terms of economic and legal reality, the

artificial share is a different thing to different people. To the brokerage house that loaned the

actual share to the short seller, the artificial “share” is actually nothing more than a contract right

to make the short seller return the real share (or another real share) at some date in the future at

the end of the loan period.11

It is worth remembering that the character of a securities loan is different for the

brokerage firm than for the short seller. From the short seller's point of view, the transaction is a

borrowing of stock and the pledging of cash collateral to secure the short seller's obligation to

return the stock at a future date. The short seller will earn modest interest on that cash collateral,

but also pay the brokerage firm a fee for letting him borrow the share. At the end of the

transaction, the short seller returns the stock, and receives in return the cash collateral he posted.

From the brokerage's standpoint, on the other hand, the transaction is a short-term loan of cash

(i.e., the cash collateral posted by the short seller) from the short seller to the brokerage house,

collateralized by the stock the brokerage pledges to the short seller. When the transaction is

unwound, the short seller repays his borrowing of stock and the brokerage house repays its

11 To the brokerage house’s customer, the share remains the “securities entitlement” that he has always had to demand that the brokerage house hold, deliver or sell the share. See revised UCC § 8-501.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

25

borrowing of cash. Thus, while these two cross-loans are outstanding, the brokerage's firm's

right in the “real share” is simply the right to get its collateral back when it repays its loan from

the short seller.

The “artificial share” held on the brokerage house's books is a reflection of this right to

the return of collateral.12 As such, it does not have the obvious characteristics of a “security” as

that term generally is understood. Indeed, to the extent that it represents a contract right to

obtain a security that itself might change in value over time, the artificial share resembles

creatures like “stock appreciation rights”, which have been held to not be securities. See Clay v.

Riverwood Int’l Corp., 157 F.3d 1259, 1264 (11th Cir. 1998). See also Marine Bank v. Weaver,

455 U.S. 551, 560-61 (1982); Caiola v. Citibank, N.A., 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3736* (S.D.N.Y

2001) (swap contracts); Procter & Gamble Co. v. Bankers Trust Co., 925 F. Supp. 1270 (S.D.

Oh. 1996) (swap contracts); In re EPIC Mortgage Ins. Litig., 701 F. Supp. 1192, 1247 (E.D. Va.

1988), aff’d in part, rev ‘d in part, sub nom. Foremost Guar. Corp. v. Mentor Say. Bank, 910

F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1990).

Although it is possible to liken these artificial shares to stock options, the analogy is a

weak one. First, artificial shares do not have the same characteristics as stock options. Artificial

shares are not — like stock options — expressly included within the definition of “security” in §

3(a)(10) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. 15 U.S.C. § 78(c). Second, where options are

traded on established markets, artificial shares are not traded at all and probably could not be. In

fact, the value of artificial shares should not fluctuate at all, since they are a fully-collateralized

contract right to obtain the return of a specified share of stock at a fixed time.

12 In fact, the Master Securities Loan Agreement permits the return of cash or other things of equivalent value instead of stock, demonstrating the insignificance of the stock itself in the transaction.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

26

Even if these artificial shares were some form of a security, it remains unclear that they

would be a security upon which an issuer could be sued. In the area of puts and calls, courts are

divided on the issue whether a company that issues the stock underlying the put or call relates

can itself be sued for securities fraud by holders of the puts or calls.13 See, e.g., Laventhall v.

General Dynamics Corp., 704 F.2d 407, 414 (8th Cir. 1983); Data Controls N., Inc. v. Financial

Corp. of Am., Inc., 688 F. Supp. 1047, 1050 (D. Md. 1988), aff’d, 875 F.2d 314 (4th Cir. 1989);

Starkman v. Warner Communications, Inc., 671 F. Supp. 297, 304-7 (S.D.N.Y. 1987); Bianco v.

Texas Instnu. Inc., 627 F. Supp. 154, 161 (N.D. Ill. 1985). But see Deutschman v. Beneficial

Corp., 841 F.2d 502, 508 (3d Cir. 1988). In Fry v. UAL Corp. 84 F3d 936, 939 (1996), the

Seventh Circuit held that option traders did have standing to sue under Rule 10b-5. Curiously,

the court found this to follow from the fact that short sellers were held to have standing in

Zlotnick v. TIE Communications, 836 F.2d 818, 821 (3d Cir. 1988), although Zlotnick

specifically distinguished between option traders and short sellers.14

Many of the characteristics of options that have caused courts to reject them as proper

grounds for a securities fraud action apply with at least equal force to artificial shares. Like

stock options, the issuer did not issue the artificial shares and has no ability to control their

issuance. See Laventhall, 704 F.2d at 410-11; Bianco, 627 F. Supp. at 159. Short sale

transactions are more risky than buying shares of stock. See Laventhall, 704 F.2d at 410; Data

Controls, 688 F. Supp. at 1050; Bianco, 627 F. Supp. at 161. Finally, artificial shares do not

13 A more extensive review can be found in Elizabeth M. Sacksteder, Securities regulation for a changing market: option trader standing under rule 10b-5, Yale Law Journal 97, March 1988, 623-642. 14 Zlotnick was also questionable authority in another respect. Zlotnick held that short sellers had standing to sue precisely because they had been both sellers and purchasers of the actual security, since the short sellers sold the security when they shorted the stock and purchased the security when they covered. 836 F.2d 818, 821. Both steps, obviously, involved transactions in “real” shares of stock, and not artificial shares.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

27

represent capital investment in the issuer. See Laventhall, 704 F.2d at 411; Data Controls, 688

F. Supp. at 1049.15

4.3 Class Certification

The twin facts (1) that there is no right to bring or maintain a federal securities action

based on the holding of “artificial” shares and (2) that it is all but impossible to distinguish

between real and artificial shares make it difficult for a court to grant class certification to a

plaintiff class in circumstances where there has been a high level of short-selling. Although

there are various reasons for this, the most fundamental reason is that class certification in these

circumstances will lead to an enormous volume of false claims for damages.

As mentioned before, there are at least three classes of persons who might be included in

a securities class action case against the issuer of a stock. The first would be the short sellers

themselves, since they were indeed “purchasers” of the stock during the class period. See, e.g.,

Zlotnick, 836 F.2d at 820-21. The second group would be the investors whose stock was loaned

by their brokerage firms to short sellers. The third group consists of those investors who

purchased the borrowed shares from the short sellers.

At the outset, one question is simple to answer. Most courts have concluded that the short

sellers themselves should not be included within a plaintiff class of purchasers. Courts have

15 There is an interesting circumstance created by the broker’s repeated lending, then collection, of the investor’s shares. Since title to the shares passes to the short seller with each loan, and title also presumably returns to the brokerage house with each return, it would seem from a legal standpoint that the brokerage house is constantly selling and re-purchasing the shares during the periods of time it is lending securities. It is an anomaly of short-selling, though, that when the brokerage house repurchases the shares (i.e., obtains their return from the short-seller), it does not do so at the market price, but rather does so at the contractual price agreed with the short seller (i.e., the market price at the time the securities were loaned). Consequently, the price the brokerage house “pays” for the shares when they are returned is not a product of any information known to the market at that time of the repurchase and, thus, the brokerage house cannot be considered to have relied upon it. Since reliance upon information known contemporaneously to the market is an element of a § 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 claim, any such re-purchases of shares when the share lending is unwound should not be a purchase that would give the brokerage house (or, by implication, its clients the investors) rights to sue.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

28

reasoned that short sellers, because they are gambling that the stock will drop in value, cannot

take advantage of the fraud-on-the-market method for providing reliance and must instead show

individual reliance. See, e.g., Zlotnick v. TIE Communications, 836 F.2d 818, 823 (3d Cir.

1988). This generally is fatal to participation in a class action. In the Computer Learning Centers

case it was the inclusion of short sellers in the class that was the basis for the court’s denial of

class certification. 183 F.R.D. at 491-92.

The question becomes more difficult when one looks at the two remaining categories of

potential class members. Much of the analysis turns, as it must, on the method by which class

members are identified and upon which claims for damages are submitted.

In a customary class action lawsuit under the federal securities laws, an investor proves

his membership in the class and claims his damages by submitting to plaintiffs’ counsel copies of

the confirmation slips he received from his broker showing that he purchased the stock at a

particular time for a particular price. But, as pointed out before, in a short sale, there are two

different people who will hold confirmation slips evidencing the purchase of the same share.

Both holders of real shares and holders of artificial shares will have in their possession evidence

showing that they have purchased the stock and, further, the transfer agent’s records (from which

the list of class members ultimately is compiled) will show that both people were members of the

plaintiff class.

There is no easy way to disentangle this overlapping ownership. Unlike the regime

during the days of paper certificates, stock held in “street name” does not have certificate

numbers or any other form of numerical identifier to distinguish one investor’s stock share from

another. In fact, revised UCC Article 8 (which governs dealings in investment securities)

stipulates that, in a book-entry system, a shareholder owns only a pro rata share of his broker’s

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

29

overall holdings of any given security. UCC § 8-503(b). “The idea that discrete objects might

be traced through the hands of different persons has no place in the Revised Article 8 rules for

the indirect holding systems.” § 8-503, Official Comment 2. In other words, since all securities

of any given issuer are fungible, it is not possible to determine whose stock is being loaned in the

first place. Lacking a system to trace down which stock is being loaned, it is impossible to

determine in any individual case whose stock is being sold or is being purchased in a short sale

and, ultimately, who it is who holds real shares and who holds artificial shares.

This becomes both a legal problem and a practical problem with profound legal

implications. On the purely legal level, this becomes an issue of legal standing to bring a claim.

By definition, a class in a securities action may consists only of those persons who purchased the

defendant company’s securities, and were damaged thereby. This is a necessary element of

standing that each class member must meet before he can bring and maintain suit in the first

place. See, e.g., Blue Chip Stamps v. Manor Drug Stores, 421 U.S. 723, 750 (1975). The burden

of proving standing rests with each plaintiff, not with the defendant. See Sea Shore Corp. v.

Sullivan, 158 F.3d 51, 54 (1st Cir. 1998); Takhar v. Kessler, 76 F.3d 995, 1000 (9th Cir. 1996).

Where there has been a high incidence of short selling, the defendants will raise the defense of

lack of standing against each member of the class. As noted before, there are serious issues

whether the holders of the “artificial” shares – whoever they might be – owned a “security” at all

or, alternatively, owned a security that they could sue upon. In addition, since the “artificial”

members of the Class may not all be artificial for the same reason, each class member’s proof of

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

30

standing will vary considerably.16 And since this would cause individual questions to

predominate over common ones, class certification would be inappropriate under F.R. Civ. P.

23(b).

Even past this threshold, there are pervasive problems of class certification. In most

cases, both the investor whose shares were loaned and the investor who purchased those shares

from the short seller will believe themselves to be holders of the security in question and also

have confirmation slips from their brokers that document their purchase of the share. Both will

thus seek membership in the class and also, ultimately, submit claims for payment of damages.

This fact guarantees a large number of false claims, since owners of “artificial” shares will be

claiming damages they are not entitled to. Moreover, because there is no way of knowing who is

a “artificial” claimant and who is a “real” claimant, a court asked to certify such a class would do

so only by creating a massive liability for the defendant issuer for damages to people who had no

right to damages.

5. Conclusion

The only certain way to mitigate these problems would be to limit the class to those

shareholders who held paper certificates or whose brokerage accounts do not permit the lending

of securities. This would eliminate the problem of “artificial” shares altogether, although at the

cost of seriously reducing the size of the class. Another means of mitigating the burdens would

be to develop a model that applies a pro rata discount in damages to claimants who had accounts 16 Because of the manner in which short sales work, the question of who holds the real share and who holds the artificial share may depend on the timing and circumstances of each short sale. For example, an investor who purchased from a “naked” short may never have owned a real share of stock; an investor who purchased from a short seller but who had not yet taken delivery of the stock on the day the company’s stock price fell may not have been a purchaser of stock on the day the damages occurred; and so on. In each of these cases, there will be a need for each plain tiff to demonstrate that it purchased stock on the relevant dates and this, in turn, requires a particularized factual inquiry into the circumstances of each claim.

Short Sales, Damages and Class Certification in 10b-5 Cases

31

with brokerage firms that loaned securities, such discount to reflect the number of shares that

were loans and when they were loaned. But the use of any such model will result in an

impossible administrative problem. It would require extensive discovery of various brokerage

houses and short sellers, and require the court and the litigants to engage in a detailed attempt to

reconstruct the trading positions of thousands of dealers, brokerage houses and investors in

millions of shares of stock over the months of the class period. Various courts have made clear

that it is inappropriate to certify a class when damages cannot be determined by a formula and

the court would have to preside over a series of mini-trials on damages. See, e.g., Windham v.

American Brands, Inc., 565 F.2d 59, 70 (4th Cir. 1977). In the Computer Learning Centers case

the court did not address the standing and certification issues pertaining to the holders of

artificial shares since class certification was denied on the basis of the inclusion of the short

sellers themselves. While the court gave leave for an amended class to be proposed, the case

settled before this was done.

Table 2

Brokers and Banks Who Mailed ICS Proxy Materials to Customers Holding Shares in Excess of the Firms' Holdings at DTC1

Firm DTC Account

Number Shares Mailed and/or Voted2

Shares Held3

Actual or Potential

Over Vote Prudential Securities 30 554,670 447,326 107,344 Smith Barney 418 188,729 110,329 78,400 Morgan Stanley and Company Incorporated 50 106,002 50,760 55,242 Merrill Lynch 5198 265,947 241,760 24,187 Bank One Trust Company NA 2609 35,300 21,700 13,600 Paine Webber 221 212,643 199,483 13,160 Donaldson Lufkin and Jenrette 443 588,640 581,090 7,550 Piper Jaffray Incorporated 311 35,670 30,970 4,700 Herzog Heine Geduld Incorporated 327 11,600 9,600 2,000 National Financial Services 226 237,385 235,685 1,700 US Clearing Corporation 158 89,351 87,651 1,700 Nesbitt Burns Incorporated 5043 1,450 100 1,350 Dreyfus Brokerage Service Incorporated 272 43,633 42,533 1,100 Lehman Brothers 74 6,100 5,002 1,098 BT Alex Brown 573 140,272 139,272 1,000 ABN AMRO Incorporated 792 14,600 13,800 800 Advest 107 2,830 2,030 800 CIBC Oppenheimer 438 42,850 42,349 501 Olde Discount 756 52,591 52,091 500 Advance Clearing 188 94,026 93,776 250 Nations Bank Montgomery 773 84,935 84,735 200 Lewco Securities Corporation 277 433,157 433,133 24

Total 3,242,381 2,925,175 317,206

1 In some cases, these firms actually over voted their record date position. 2 These are the aggregate amounts of shares held by each firm's customers as reported by the firms themselves. 3 These amounts are the number of shares DTC reported holding for each firm in its “omnibus proxy.”

01-Jun-95 20-Feb-96 06-Nov-96 29-Jul-97 20-Apr-98 07-Jan-99 28-Sep-99 20-Jun-00

$10

$20

$30

$40 1

3

2 4

5

6

Figure 1 Computer Learning Centers Stock Price

The price shown has been adjusted for stock splits on April 15, 1997, and January 9, 1998. The price shown after January 8, 1998, is the actual stock price. The price shown from April 15, 1997, through January 8, 1998, is one-half the actual stock price. The price shown before April 15, 1997, is one-third the actual stock price. 1.March 9, 1998. News stories appear describing a complaint filed by the Illinois Attorney General

against CLC for allegedly defrauding students at the Schaumberg center. 2.April 6, 1998. CLC discloses that the Illinois state Board of Education entered a preliminary order

limiting its ability to enroll new students at the Schaumberg center. 3.May 5, 1998. Rumors begin that the Illinois State Board of Education lifts its suspension. 4.June 8, 1998. Settlement with Illinois Attorney General is announced. 5.August 11, 1998. New lawsuit alleging destruction of student-related files requested by federal

auditors. 6.August 18, 1998. CLC announces weak earnings due to legal problems.

03/Feb/97 30/Jul/97 26/Jan/98

$10

$20

$30

$40

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Price per share Short sales as % of shares outstanding

Class Period

Figure 2 Short Sales of Computer Learning Center Stock

Figure 3A Short Sale Illustration — Before the Short Sale

Person J Company X owner of record on 1 share has issued 2 shares Person K

owner of record on 1 share

Short Seller S Person L

Figure 3B Short Sale Illustration — Execution of a Short Sale

Person J Company X Short Seller borrows 1 share Person K from person K

Short Seller S Person L Short Seller sells 1 share to Person L

Figure 3C

Short Sale Illustration — While the Short Sale is Outstanding Person J Company X owner of record on 1 share Person K

Short Seller S Person L

• has lent 1 share to Short Seller S • enjoys profit and loss on 1 share, plus

dividends, plus fee for lending, all from Short Seller S

• no voting rights

has 2 shares outstanding on which it owes dividends and

with rights to vote

• owes 1 share to Person K • enjoys reverse of profit and

loss on 1 share, less dividends, less fee for lending, all to Person K owner of record on 1 share

04-Feb-97 30-Apr-97 24-Jul-97 16-Oct-97 12-Jan-98 07-Apr-98

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

$35

$/Share

Inflation

CLC Stock Price

Hypothetical True Value

Class Period

Figure 4 Hypothetical Inflation in the Computer Learning Centers Case

30-Apr-97 11-Jun-97 23-Jul-97 3-Sep-97 14-Oct-97 24-Nov-97 7-Jan-98 19-Feb-98 1-Apr-98

2

4

6

8

10

12

Millions of Shares

Float With Short Sales

Float Without Short Sales

Figure 5 Float in the Computer Learning Centers Case, Calculated With and Without Short Sales

30-Apr-97 11-Jun-97 23-Jul-97 3-Sep-97 14-Oct-97 24-Nov-97 7-Jan-98 19-Feb-98 1-Apr-98

2

4

6

8

10

12

Millions of Shares

Affected Shares Without Short Sales

Affected Shares With Short Sales

Figure 6 Affected Shares in the Computer Learning Centers Case, Calculated With and Without Short Sales

30-Apr-97 11-Jun-97 23-Jul-97 3-Sep-97 14-Oct-97 24-Nov-97 7-Jan-98 19-Feb-98 1-Apr-98

25

50

75

100

125

150

175

200

$ Millions

Damages Without

Short Sales

Damages With Short Sales

Figure 7 Hypothetical Cumulative Damages in the Computer Learning Centers Case,

Calculated With and Without Short Sales

Figure 8A Short Sale Illustration — Before the Short Sale

Person J Company X Broker A Beneficially owns 1 share has issued 2 shares through Broker A Person K

Beneficially owns 1 share through Broker A

Owner of record of 2 shares in street name on behalf of J and K Short Seller S Person L

Figure 8B Short Sale Illustration — Execution of a Short Sale

Person J Company X Broker A Person K

Short Seller borrows 1 share from Broker A Short Seller S Short Seller sells 1 share to Person L Person L

has 2 shares outstanding on which it owes dividends and

with rights to vote

• owner of record of 1 share in street name on behalf of J and K

• has lent 1 share out • owes dividends to both J and K • earns the fee for lending

beneficially owns 1 share through Broker A

beneficially owns 1 share through Broker A

owner of record on 1 share

• owes 1 share to Broker A • enjoys reverse of profit and loss on 1

share, less dividends, less fee for lending, all to Broker A

Figure 8c Short Sale Illustration — While the Short Sale is Outstanding

Person J Company X Broker A Person K

Short Seller S Person L

![10B-LR 10B-SUB - Bryston10B].pdf · The 10B crossover is available in three stock versions; 10B-SUB incorporating frequencies more ... MONO LOW PASS MODE (10B-SUB AND 10B-STD ONLY):](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5afd7a367f8b9a434e8d9dda/10b-lr-10b-sub-10bpdfthe-10b-crossover-is-available-in-three-stock-versions.jpg)

![10B-LR 10B-SUBold.bryston.com/PDF/Manuals/300001[10B].pdf · The 10B-STD and 10B-SUB crossovers generate a summed low pass output signal by first summing or adding together the left](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5fca308acddab466873f1279/10b-lr-10b-10bpdf-the-10b-std-and-10b-sub-crossovers-generate-a-summed-low.jpg)

![JICA 201610B 10B 10B 13B 22 10B 11B 11B 26B M2:30 JTñ-ñ-3— … · 2016-10-13 · JICA 201610B 10B 10B 13B 22 10B 11B 11B 26B M2:30 JTñ-ñ-3— JD+ñ3—] (3) @ @ @ 201 2016 11](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f7b7664c26e297ff6248b8f/jica-201610b-10b-10b-13b-22-10b-11b-11b-26b-m230-jt-3a-2016-10-13-jica.jpg)