Sequenza de Berio

-

Upload

monica-san -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Sequenza de Berio

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [Universidad Publica de Navarra]On: 11 April 2010Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 773400315]Publisher RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Contemporary Music ReviewPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713455393

Performing Sequenza VIIChristopher Redgate

To cite this Article Redgate, Christopher(2007) 'Performing Sequenza VII', Contemporary Music Review, 26: 2, 219 — 230To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/07494460701295374URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07494460701295374

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Performing Sequenza VIIChristopher Redgate

Christopher Redgate offers an approach to dealing with some of the issues performers face

in preparation of Sequenza VII through a study of the different versions of the work thatare available.

Keywords: Berio; Sequenza VII; Chemins IV; Extended Techniques

Introduction

When Sequenza VII1 first appeared in 1969 it was arguably the most difficult work inthe oboe repertoire. Indeed even today it is still considered to be one of the major

technical challenges for the oboist. The work contains a number of problems for theinterpreter, including, occasionally, discerning exactly what the composer intends.The challenge is less formidable today given the number of recordings that are

available, but listening to recordings does not always bring clarity to the technicalproblems as it is not always easy to tell exactly what a performer is doing simply by

listening.Sequenza VII is a seminal work in the literature of the oboe.2 The work is one of the

few written using ‘extended techniques’ that has been accepted into the wider oboe-playing community including being a chosen as a set piece at major international

competitions.3 At the time of writing, ‘extended techniques’ were still relatively newand little explored; they are, however, beautifully integrated into the composition.

The work demands from the oboist a very high level of technical and musicalvirtuosity, in terms not only of finger dexterity, breath and embouchure control, butalso of an ability to interpret the complex lines and to cope with the timing and

pacing.The work is an excellent example of idiomatic writing for the oboe. The choices

made by Berio in this respect could hardly be better.4 He has shaped the work aroundthe exact range of the instrument as it was generally accepted to be at the time: Bb3 to

G65 and the choice of the B natural, B4, which forms a ‘tonic’6 around which thework evolves, could not be better chosen. This particular pitch can be achieved on the

instrument using an extraordinary number of fingerings.

Contemporary Music ReviewVol. 26, No. 2, April 2007, pp. 219 – 230

ISSN 0749-4467 (print)/ISSN 1477-2256 (online) ª 2007 Taylor & FrancisDOI: 10.1080/07494460701295374

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

Sequenza VII is published on one large sheet. The most recent publication includes

two versions of the work. On one side is Sequenza VIIa (Revised Version 2000) (RV)and on the reverse is Sequenza VIIa supplementary edition by Jacqueline Leclair

(JLV) (2000). The JLV was developed as a study version for oboists and the RV isthe performing version.7 The JLV differs from the RV in that it includes time

signatures (rather than the indication of seconds, as in the RV), the proportionalnotation is replaced by a fully realised version, and the ‘as short as possible’ symbol isremoved.8

I first studied the work in the 1970s and have always performed from a copy fromthat period (OV). The RV/JLV corrects some small errors in the OV9and includes

some important revisions. These revisions have been made in order to facilitate amore practical approach to performance. Paul Roberts, who worked extensively on

this edition with Berio, suggests that the JLV ‘should be taken as the most reliableversion’.10 Included with both the OV and the RV/JLV are a list of instructions for

the realisation of the sounds and extended techniques, written by Heinz Holliger.In the more recent publication (RV/JLV), these are reproduced exactly as they were inthe earlier edition. They have not been altered to reflect the revisions of some of the

double harmonic fifths in the text.In addition to the versions mentioned above there are a number of others. The

earliest form of the work, published as Studie zu Sequenza VII11 (ESV), is obviously aversion of the Sequenza. Two points are significant for our discussion: the

metronome indication—crochet equals 62—and the triple-time nature of the piece.There are once again instructions on performance included with the publication

(written by Holliger).Sequenza VII was reworked for soprano saxophone12 (SV). The composer worked

in conjunction with the saxophonist Claude Delangle. Of particular relevance to ourdiscussion is Berio’s apparent preference for the version for saxophone13 and thedirections for performance written by Delangle. There are some minor changes to

the text, including the altered double harmonic 5ths, which are consistent with theRV/JLV.

Berio reworked Sequenza VII in a version for oboe and 11 strings in 1975 and in1992 for saxophone and strings: Chemins IV. The two versions, for oboe and for

soprano saxophone, have performing directions written by Holliger and Delangle,respectively. The edited version of Chemins IV also has the microtonally altered

double harmonics in both versions. Of particular importance to our discussion arethe tempo indication (quaver¼ 110 – 120), the loss of the proportional notation andthe introduction of time signatures. The pauses, instead of being played through

by the performer, as is the case with the majority of them in the Sequenza, offer abreathing space and, interestingly, often have substantial string activity. In the oboe

version the strings are muted but in the saxophone version they are not.From the opening bar the performer is faced with a number of issues of

interpretation: Choices need to be made concerning the B natural fingerings, how thesustained B natural is to be performed, how the proportional notation is to be read

220 C. Redgate

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

and interpreted and how to cope with the time indications in seconds. These

decisions are foundational to the detailed interpretation of the work.

The B(s)

Even a most cursory look at the score will establish the central role of the B natural inthe work. Berio, in his programme notes for the Sequenza, states:

. . . I carry on the research of a latent polyphony putting into perspective thecomplex sound structures of the instrument with an ever-present ‘tonic’: a Bnatural that can be played pianissimo by any other instrument, behind the stage orin the audience. It is a harmonic perspective that contributes to a subtler analyticinsight of the various stages of transformation of the solo part.14

Two brief observations on the above comment are called for. First, the B natural can

also be played, according to the notes in the score, on an electronic source or withpre-recorded instruments.15 I have also seen it being performed using several stringedinstruments. Second, the comment that the B natural can be performed ‘in the

audience’ does not appear in the instructions that accompany the score; rather, theystate that the ‘sound-source must not be visible’.

This is of course not the only B in the work. The opening line of the oboe part consistsof nothing else. This is, however, ‘coloured’ by the use of six different fingerings and by a

range of articulations, ties with fingering changes and a wide variety of dynamics.Berio does not himself give specific fingerings but leaves them to the choice of the oboist;

Berio simply gives numbers from one to five. Altogether, then, he asks for these fivefingerings, plus the ‘normal’ fingering and also a harmonic fingering (see bar 93). One of

the most important interpretative questions that these fingerings raise is how to choosethem. The score offers no instructions from Berio. Holliger’s fingerings are a helpfulstart but for various reasons these are sometimes not practical.

The B natural fingerings in the ESV occur in a numerically different order to thoseof the Sequenza (ESV begins 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 3, 1 . . . while Sequenza VII begins 3, 5, 3, 4, 2,

3, 4 . . . ). Holliger offers several illuminating comments in his commentary on theESV.16 Concerning the B natural fingerings (and applying the same principle to

the other alternative fingerings needed), Holliger suggests, ‘These timbres shoulddeviate more and more from the timbres of the normal fingerings, in relation to the

numeration (1) to (5)’.17 There is obviously progression intended here, according tothis comment, but exactly what does ‘deviate’ mean? Getting brighter and brighter orperhaps darker and darker? This instruction can be found repeated in other

discussions about the Sequenza and the choice of B fingerings. Holliger also states:‘The fingerings on the chart are only suggestions. Each student can choose for himself

other fingerings which are better suited to his instrument’.18

So the oboist does not have to use Holliger’s19 suggested fingerings but if s/he

doesn’t or can’t then other fingerings should be chosen according to the aboveprinciple—that of differentiation.

Contemporary Music Review 221

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

In studying the use of the B naturals in the Sequenza there are perhaps some

generalisations that can be made about the use of specific fingering numbers and inturn perhaps these generalisations could help the oboist to make reasonable choices.

Many of the fingering options available for the B natural offer slight microtonaldifferences. Some of them would be difficult to use in combination with each other

simply because of the clumsiness of the fingerings—making difficult the smoothtransition required in some sections of the work. Therefore many of the possiblefingerings can be eliminated on the grounds of pitch or practicality. The dynamics are

a significant factor in choosing the fingerings because some will only work at a lowerdynamic.

Some general observations can be made concerning the fingerings numbered 1 – 5:

(1) needs a wide range of dynamics and is usually the fingering used in passageswhich include bisbigliando;

(2) is used with a broad range of dynamics;(3) is generally used as a quieter fingering;(4) is for the quiet notes and is used in the first two of the pauses at a ppp

dynamic. It is occasionally used as a grace note anacrusis to the main B naturalpitch;

(5) is always quiet and is used on several occasions as the fingering following a tied‘sffz’ grace note on the same pitch.

The same principle can be applied to the other pitches that require this treatment.

The ESV includes another instruction, which is not included in the introduction tothe Sequenza: the 1st finger LH key should be slightly unscrewed in order to obtain

some of the fingerings.20 (This can also help with the double harmonics and themultiphonics later in the work.)

The Text

Before discussing the issues surrounding the proportional notation there are somegeneral observations concerning the text, which it is important for the performer to

understand.The musical text that a performer works from and possibly performs from can

play an important part in the interpretation and performance of a work. A textcommunicates, at the most basic level, the information that a composer wishes topresent to the performer. Even the precise layout of each bar is very important.

Performers then add to the text reminders, re-writings, even in some cases colouringin of specific details in order to highlight them. The text becomes personal. The look

of a piece of music can play a significant part in the performance of the work, notonly at the superficial level but also at the far more important level of inspiration. The

layout of the text can alter the response of the performer. This is especially so whenthe text is as visually stimulating as Sequenza VII.21

222 C. Redgate

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

The way Sequenza VII is printed (on one side of one large sheet) not only obviates

the necessity for any page turns but also creates a very special visual effect. The unityof the work as displayed on one sheet in this way echoes the unity of the work that is

brought about by the continually sounding B natural. There is a link between thevisual and the aural. The special ‘as short as possible’ indications and layout of the

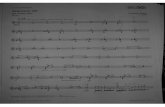

proportionally notated sections also add significantly to the look of the text (seeFigure 1).

Paul Roberts sums up the RV text very well when he states:

Of course the intention behind this notation is for the benefit of the performer whowithin a controlled freedom will never play the piece in exactly the same way asanother, even though the content and the character of the piece will always remainidentical. (Roberts, 2003)

There is an essential tension built into the Sequenza between the ‘freedom’ of the

proportionally notated sections and the precisely written material.22 This tensionmust not be lost in performance. It is important to point out, however, that theproportional notation gives only very limited freedom to the performer. The

noteheads are placed carefully within the context of the space and any studiousperformer should have a good idea of where to place these notes.

Berio has, on occasion,23 asked performers to memorise the work. This removesthe text completely from the performer on stage and begs the question as to how the

performer memorises and performs the work maintaining the tensions mentionedabove. Response to proportional notation, unless the performer has a visual memory,

is going to be altered and any response to the text may well be learned in advance ofthe performance. One is going to have to use very advanced memorisation techniques

in order to maintain the studied spontaneity and tension implied in the text.The JLV aims to help performers deal with the problem of both the proportional

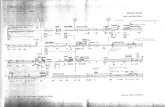

notation and the time indications. A brief comparison of Figure 1 (RV) and Figure 2

(JLV) will demonstrate the difference.In the JLV the proportional notation is written out and the ‘seconds’ indications

have been realised as time signatures.24 The JLV is therefore a very useful learningtool but I would also encourage students to work with the proportional notation,

partly to gain experience of some basic improvisation from a text, as well as toprepare for performance from the RV.

Multiphonics, Double Harmonics and Overblowing

Two categories of sound production require in-depth discussion—namely, the use ofmultiphonics and double harmonics, and overblowing.

The challenge the oboist faces here is that some of the double harmonics (andoccasionally the multiphonics) cannot, on some instruments or reed designs, be

reproduced exactly. In particular the perfect fifths sometimes do not soundlike perfect fifths. This is in part a problem of instrumental design and in part

Contemporary Music Review 223

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

due to differences of reed styles. The problem was recognised by Berio and in the RV/JLV the notation of some of the fifths has been revised to include a microtonal

change.25

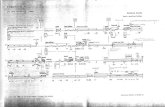

In the OV the ‘perfect fifth’ double harmonics are notated as perfect fifths, while in

the RV, JLV and SV as well as in the modern editions of Chemins IV, a number of thedouble fifths have been notated microtonally altered (see Figure 3).

Though one would have expected the RV and the JLV to be identical in thesealterations there are in fact a number of differences. The SV and the JLV are identicalwith one exception, and that is bar 150, where the SV agrees with the RV. This, I am

convinced, should be seen as a printing error in the JLV. Chemins IV at this samepoint, bar 193, also has a perfect fifth in the oboe version and a microtonally altered

fifth in the sax version. I am equally certain that the oboe version should bemicrotonally altered here as well. Two of the multiphonics differ in the SV from the

oboe versions: bars 161 and 168. As we have observed above, in none of the

Figure 2 Luciano Berio, Sequenza VIIa, first four bars of line 1 of the JLV. Copyright2001, Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

Figure 3 Luciano Berio, Sequenza VIIa, bars 11 – 13 of line 4 of the RV. Copyright 1971,Universal Edition (London) Ltd., London. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

Figure 1 Luciano Berio, Sequenza VII, first four bars of line 1 of the RV. Copyright 1971,Universal Edition (London) Ltd., London. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

224 C. Redgate

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

performance instructions are these microtonal alterations mentioned: The perfect

fifth double harmonics are printed with no reference made concerning the changes. Ihave also consulted a number of the ‘compendium style’ books that give lists of

fingerings for a wide range of multiphonics and these altered fifths do not appear asfingering options. It is well documented (see, for example, Burgess & Haynes, 2004)

that the double harmonic fifths are very difficult to produce on some instrumentsand possibly also on some reed styles. This is of course a great problem for oboistslearning or wishing to perform the work. Paul Roberts suggests:

Luciano Berio was a practical musician and realised that this notation of themultiphonics could not be 100% precise. In a performance of Sequenza VII theplayer (oboist, or saxophonist) must produce a convincing effect withthe multiphonics. The quarter-tone indications should be understood as marginsof error, since it is taken for granted that a perfect intonation is almostimpossible.26

This to me is a very convincing argument for these changes and for the resultantpotential for a range of possible options for these harmonics. The oboist therefore

should get as close to the ideal as possible—perfect fifths—but the composerrecognised that there is a problem and in making these alterations the problem is

acknowledged and a small range of alternatives that could include limited pitchchanges is sanctioned. The oboist should seek fingerings27 that get as close as possible

to the ideal but not shy away from the performance of the work if the double fifthsare not perfect.

Overblowing

This is symbolised in the text by a ‘Z’ with a line through it, brackets and a line toindicate its duration (see Figure 4).

The ‘overblow’ issue also has problems of interpretation.28 On the oboe, to‘overblow’ implies blowing hard enough that the pitch splits thus creating some

distortion or indeed a multiphonic sound. The problems are simple: many of thepitches chosen for overblowing are unsuitable in that they produce little effect when

Figure 4 Luciano Berio, Sequenza VIIa, bars 8 – 11 of line 3 of the RV. Copyright 1971,Universal Edition (London) Ltd., London. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

Contemporary Music Review 225

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

pushed in this way (see Van Cleve, 1991). Two of the ‘overblow’ sections are not

single notes but short phrases (bars 94 and 144). Many of the ‘overblow’ pitches alsohave other pitch alteration or distortion attached to them—either microtonal trills or

flutter tonguing. The interpreter’s question must be: ‘What sound is Berio seekingwhen he indicates ‘‘overblow’’?’ Holliger’s instructions offer a range of fingerings,

some with instructions to increase lip pressure or to increase air pressure.29 Nosuggestions are offered for the two passages that have short phrases (bars 94 and 144).In the instructions to the SV, Delangle also suggests fingerings for the individual

notes. His performance directions imply that some of the overblown pitches result inmultiple pitches of an unspecified nature. For the phrases in bars 94 and 144, he

suggests ‘growling’ throughout the whole of 94 (with flutter tongue where indicated)and in 144 growling throughout the first part of the passage. The last six notes of the

passage in the saxophone version include flutter tonguing, and this, it would appear,takes over from the growl. The flutter tonguing in this passage appears in the sax

version (also in Chemins IV—sax version) but not in any oboe versions. Bringingtogether these different instructions—alternative fingerings, growling and increasedembouchure pressure—along with the observation that most of the individual notes

have some form of ‘distortion’ already, I suggest that what is being looked for at thesemoments is a fairly extreme form of distortion where the written pitch(es) is a guide

that should be distorted. I see no reason why the oboist should not also add a ‘growl’.This I suggest would be in keeping with the spirit of the music. There are two

additional overblown pitches in the SV that are marked flutter tongue in the oboeversions—including the G6 climax of the work.30

In the SV one of the later multiphonics employs different pitches.

Tempo and the Length of the Work

The duration of the work is an important area for discussion. When all of the

seconds are added up the work is about 7 minutes long.31 However, a number ofwriters32 observe that that many of the recordings (including those of Holliger the

dedicatee) are longer than the mathematically correct length of the piece.33 Libbyvan Cleve suggests ‘that Berio (like many composers) gives slightly optimistic

tempo indications, and that some flexibility in time . . . is permissible’ (Van Cleve,1991). My own approach is that the basic unit of the second is an ideal unit to

use in a work with a grid notation such as this, rather than using a unit of say1.2’ which would lead to some complex durations! I am convinced that Beriointended the ‘seconds’ pulse to be a guide and that it is much more important to

maintain the relative bar lengths.34

Comparison of the tempo indications in the related works is quite informative:

The ESV is ‘crotchet equals 62 (sempre)’ and Chemins IV is ‘quaver equals 110 – 120’.There is a little flexibility in these tempos, possibly suggesting that some flexibility

could be allowed in performance. The JLV could be a tremendous help in practisingto maintain the integrity of the differing bar lengths.

226 C. Redgate

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

General Interpretation Issues

Having negotiated the issues raised above—choices of fingerings, multiphonic

problems, tempo and so on—the performer is in a position to begin work on themain issues of interpretation.

As has already been observed, it is vital in performance to maintain the tensionbetween the strictly notated sections and the proportionally notated sections. Thisdifference needs to be practised.35

The score contains no words of instruction—there are no indications as to thenature of the colours required or the style in which any particular passages are to be

played. The performer is required to consider carefully the colours, character andmoods of the piece. These should be considered in conjunction with the overall

journey. This aspect of the work is of considerable importance to the interpretation inthat, as with the variety afforded from performance to performance of the

proportionally notated material, there is another level of potential change fromperformance to performance.

The use of vibrato is an issue of particular relevance especially where the pauses are

concerned. A number of the pauses work well with no vibrato at all and on a coupleof occasions could ‘melt’ into the sustained background B. The pauses themselves

are a very significant part of the work’s architecture and contribute significantly tothe pacing, especially towards the end of the piece. Special consideration should also

be given to the use of vibrato on the multiphonics. Vibrato on multiphonics can bewonderful,36 but in the context of this work it can take away from the stillness

sometimes implied by the context.The overblowing and frequently the flutter tonguing should be viewed as very

harsh distortions. Something in the way oboists are brought up to make as anagreeable sound as possible can make performers reticent about making the kindsof sounds Berio requires. I wonder if Berio’s preference for the sax version can at

least in part be explained by the fact that the sax can make a colossal sound at thesepoints.

I have alluded already to the journey of the work. This is a particularlyimportant concept in the Sequenza. At its centre is the stasis of the continually

sounding B natural. Around this a web is woven where new pitches are introducedin a very disciplined manner,37 moving towards the ‘climax’ of the work, the high G6

in bar 123. From here onward there is an unwinding towards the end which isfacilitated by pauses, bringing greater and greater stillness to the work andlengthening each line considerably. Considering the work as a journey or as a

developing web offers the performer an approach with which to evaluate the choiceof colours, to understand the shifting moods and to plan the pacing of the work as a

whole.The Sequenza is finding a major place in the repertoire of the modern oboist. This

is a work that should be studied at college level. The ESV and the JLV both offer thestudent helpful routes into the work and the technical demands, while being very

Contemporary Music Review 227

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

challenging, can add to the refinement of traditional oboe technique. Young

composers likewise will find a great deal to study, not only in the comparison andanalysis of the different versions but also through the study of beautifully idiomatic

yet virtuoso oboe writing.

Notes

[1] Sequenza VII was written for the oboist Heinz Holliger, who gave it its first performance inBasle, Switzerland.

[2] See for example Holliger’s (1972) introductory notes in Pro Musica Nova.[3] See Burgess & Haynes (2004), p. 279 (n32).[4] See ibid., p. 279.[5] A6 and B6 had both been written for before this. Berio’s choice not to use these pitches could

have been compositional rather than based on the limitations of the instrument. B6 hecertainly would not have used. B4 is the only B natural pitch used in the piece. See Roberts(2003).

[6] Berio refers to the B natural as a tonic in his programme note to the Sequenza.[7] This information comes from Jacqueline Leclair’s ‘beriooboesequenza’ website. The

information is not stated on the published copy—an issue that could cause confusion.[8] There are a number of other minor differences between the two—but these are errors rather

than deliberate textual changes.[9] It should be noted that there are some errors in the RV that are correct in the JLV.

[10] Paul Roberts, personal email communication to the author.[11] This was apparently a draft version of the Sequenza. A version of this draft was used in the

first performance of the Sequenza.[12] Known as Sequenza VIIb.[13] Paul Roberts, in a personal email communication to the author, states, ‘It may be

disappointing for oboists to learn, but in private, Luciano Berio admitted that he preferredthe saxophone version of Sequenza VII. The reason being that the multiphonics—and all theother special timbral effects—work better on the saxophone, which is a much more powerfulinstrument . . .’.

[14] Berio’s programme notes.[15] Footnote in the published score.[16] I suggest that it is safe to assume that Berio’s influence is contained in the comment, as

Holliger worked closely with him on this work.[17] See Holliger’s (1972) introductory notes in Pro Musica Nova.[18] See Holliger’s (1972) introductory notes in Pro Musica Nova.[19] Jacqueline Leclair, on her ‘beriooboesequenza’ website, states: ‘The Sequenzas of Berio should

be approached with the understanding that the virtuoso, the interpreter, has a great deal oflatitude. Holliger’s suggestions about performance technique choices should be taken with atleast a grain of salt . . . . Many of the techniques, like the double harmonics, can be supplantedwith various multiphonics, as long as the pitch content is correct. The ‘‘B’’s, for example, canbe fingered any number of ways’.

[20] See Holliger’s (1972) introductory notes in Pro Musica Nova.[21] This discussion can be applied to the performance of a great deal of the more complex music

being written today. The visual impression of the music is an important factor inperformance that should not be overlooked by performer or composer.

[22] See Jacqueline Leclair’s ‘beriooboesequenza’ website.[23] Melinda Maxwell, Director of Woodwind Studies at the Royal Northern College of Music,

performed the work from memory at Berio’s request.

228 C. Redgate

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

[24] See Van Cleve (1991) for another discussion of time signatures.[25] This is also reflected in Chemins IV and in the saxophone versions of both works.[26] Paul Roberts, private email communication with the author.[27] Jacqueline Leclair, on her ‘beriooboesequenza’ website, is planning to offer a range of

fingerings for these fifths.[28] This problem is discussed by Van Cleve (1991, 2004) and by Leclair.[29] See instructions published with the Sequenza.[30] Top G, which appears four times in the piece, twice as a very short note and twice flutter

tongued, has a challenging technical problem. In its last appearance it should be performed fffollowed by a sudden drop to p, over the bar line, while maintaining the flutter tonguing. TheOV simply repeats the pitch and the flutter tonguing indication at the beginning of the newbar. But the RV includes a tie over the bar line and an additional harmonic symbol over thesecond G. In the copy I have the flutter tonguing mark is missing from the second G. TheJLV includes the tie, which is dotted, the flutter tonguing and the harmonic symbol. There isalso a diminuendo added to the first G. This makes the execution of this note much easier.The copy I have of the RV looks as if there has been a diminuendo but that it has not printedproperly. The SV has an overblow indication instead of the flutter, a tie and a harmonic butno diminuendo. The saxophone version of Chemins IV also includes a diminuendo. CheminsIV for oboe includes the harmonic and the flutter along with the diminuendo. I have, overthe years, heard several different solutions to this problem and I suggest that the diminuendois a very good way of dealing with the problem but, I further suggest, the sudden drop indynamic over the bar line would be Berio’s ideal.

[31] The publisher states 10 minutes as the duration on the Universal Edition website.[32] Van Cleve (2004), Burgess & Haynes (2004), and Leclair on her ‘beriooboesequenza’ website.[33] My own recording is 8 minutes (Oboe Classics).[34] Leclair, ‘beriooboesequenza’ website.[35] Ibid.[36] See the comments in Van Cleve (2004).[37] For detailed discussion of the pitches in the work and some in-depth study of the structure,

see Roberts (2003) and Osmond-Smith (1991).

References

Berio, Luciano. (1969a). Sequenza VII for Oboe (programme notes provided by Universal Edition).Berio, Luciano. (1969b, rev. 2000). Sequenza VIIa. Vienna: Universal Edition A.G.Berio, Luciano. (1971a). Sequenza VII. London: Universal Edition (London) Ltd.Berio, Luciano. (1971b). Studie zu Sequenza VII. In Heinz Holliger (Ed.), Pro Musica Nova Studien

zum Spielen Neuer Music. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Hartel.Berio, Luciano. (1975/2000). Chemins IV (su Sequenza VII), for Oboe (or Soprano Saxophone) and 11

Strings. Vienna: Universal Edition A.G.Berio, Luciano. (n.d.). Programme notes as supplied by Universal Edition, Vienna.Burgess, Geoffrey & Haynes, Bruce. (2004). The Oboe. Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven

and London: Yale University Press.Holliger, Heinz. (Ed.) (1972). Pro Musica Nova: Studien zum Spielen Neuer Musik. Weisbaden:

Breitkopf & Hartel.Leclair, Jacqueline. (n.d.). http://www.beriooboesequenza.com/Osmond-Smith, David. (1991). Berio. Oxford Studies of Composers (20). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.Roberts, Paul. (2003). On Luciano Berio’s Sequenza VII for Oboe. Mitteilungen der Paul Sacher

Stiftung, No. 16, March.

Contemporary Music Review 229

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

Van Cleve, Libby. (1991). Suggestions for the performance of Berio’s Sequenza VII. The DoubleReed, Journal of the International Double Reed Society, 13(3), 45 – 51.

Van Cleve, Libby. (2004). Oboe unbounded: Contemporary techniques. Maryland: ScarecrowPress.

Recording

Redgate, Christopher. (2006). Oboeþ: Berio and beyond. Oboe Classics.

230 C. Redgate

Downloaded By: [Universidad Publica de Navarra] At: 08:32 11 April 2010

![Berio - Sequenza XIII. Chanson [for Accordion]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/55cf9be0550346d033a7b6b5/berio-sequenza-xiii-chanson-for-accordion.jpg)