SEPTEMBER 2012 • VOLUME 12 • NUMBER...

Transcript of SEPTEMBER 2012 • VOLUME 12 • NUMBER...

S O C I E T Y F O R A M E R I C A N A R C H A E O L O G Y

SAAarchaeological recordSEPTEMBER 2012 • VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 4

the

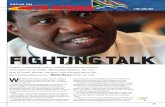

SPECIAL FORUM: INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Winner, 2012 SAA Archaeology Week Poster Contest

28 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

Collaborative approaches to archaeological practicehave become increasingly common in the past 15-20years (Atalay 2006; Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Fergu-

son 2007; Moser et al. 2002; Nicholas et al. 2007). Archaeol-ogists are engaging with descendant and stakeholder com-munities in ways that are radically transforming how we doarchaeology (Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson 2007). Inthe United States, much of the genesis for collaboration canbe traced back to the passing of the Native American GravesProtection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). By legislatingrepatriation of human remains and burial objects, the lawcreated opportunities where archaeologists and NativeAmerican groups could work together. Many members of thepost-NAGPRA generation of archaeologists have been raisedintellectually in an environment where consultation is a nec-essary part of doing archaeology (e.g., Silliman 2008). How-ever, many collaborative archaeological projects, such as theones presented in this forum, have arisen without any legis-lation structuring the relationship between descendant com-munities and archaeologists. The SAA Committee on NativeAmerican Relations (CNAR) is interested in exploring howcollaborative projects form and transform in countries andcontext where legislation does not require consultation. Withthis in mind, we approached several scholars who are active-ly involved in collaborative projects in international contextsto reflect on how the collaborative project began and whatthe outcomes have been. We received submissions fromaround the world and highlight here are six different projectsthat include collaborative efforts in six different countries:Australia, Canada, New Caledonia, New Zealand, the UnitedStates, and Tanzania. Some projects, such as those in Tanza-nia and New Caledonia, are among the first in their respec-tive countries, while others, such as those in Canada andAustralia, are part of an ongoing national shift in archaeo-logical practice.

A number of key themes connect these diverse projects andgive some indication of the core principles of successful col-laborations. The first is the importance of communication.Communication is essential to building relationships oftrust and shifting communities’ perceptions about the pur-pose and practice of archaeology. For example, in Tanzania,the members of the research team experienced a very differ-ent reaction from residents of the local village after thearchaeologists had made an effort to communicate, viaposters, the purpose and importance of archaeological infor-mation and heritage. In the Inuit Living History Project, acollaborative ethic extended to how the different members ofthe team worked together, whether they were academics,researchers, or community members. A similar situationarose in Australia, where Smith and Jackson encounteredearly on the essential role of family relationships and con-nections in developing true collaborative research practices.

Another theme is the emphasis by local or indigenous com-munities on education. Lyons et al. created the Inuvialuit Liv-ing History Project to address the desire of local communi-ties to develop tools where knowledge could be passed on toyounger generations. For Roberts, one of the key concerns ofthe Mannum Aboriginal Community Association was toeducate tourists and visitors about their perspectives on thepast. Education, in this case, was about the communitymembers sharing their knowledge and changing percep-tions about heritage. In Tanzania, the CHIRP project mem-bers are closely involved with the local school to provide sup-port and materials that can be used in the classroom. InAustralia, one of the major challenges facing the remoteAboriginal communities is access to education, so the proj-ect members worked with local communities to developtraining programs.

One final theme that runs throughout several of the articlesis the importance of the intangible aspects of heritage that

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

SPECIAL FORUM ON INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

EDITOR’S COMMENTS

Kisha Supernant

Kisha Supernant is an Assistant Professor at the University of Alberta and a member of the Committee on

Native American Relations (CNAR). She may be reached at [email protected].

can be negatively impacted via colonial histories. Reclama-tion of objects, knowledge, and landscapes are essential tothe process of decolonization for many communities. TheIPinCH project and related case studies explicitly addressissues around the definition of cultural heritage in commu-nities throughout the world.

These articles are just a small sample of the diverse types ofcommunity-based archaeological research being undertakenaround the world. Even without heritage legislation formal-izing a responsibility to descendant communities, archaeol-ogists are working toward the decolonization of the disci-pline and building strong collaborative relationships withdescendant and local communities.

References CitedAtalay, Sonya

2006 Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice. Ameri-can Indian Quarterly 30(3/4):280.

Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, and T. J. Ferguson2007 Collaboration in Archaeological Practice: Engaging Descen-

dant Communities. AltaMira Lanham, MD.

Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, and T. J. Ferguson2007 Introduction: The Collaborative Continuum. In Collabora-

tion in Archaeological Practice: Engaging Descendant Com-munities, edited by Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh and T. J.Ferguson, pp. 1–32. AltaMira, Lanham, MD.

Moser, Stephanie, Darren Glazier, James E. Phillips, Lamya Nasserel Nemr, Mohammed Saleh Mousa, Rascha Nasr Aiesh,Susan Richardson, Andrew Conner, and Michael Seymour

2002 Transforming Archaeology through Practice: Strategies forCollaborative Archaeology and the Community Archaeolo-gy Project at Quseir, Egypt. World Archaeology34(2):220–248.

Nicholas, George P., John R. Welch, and Eldon C. Yellowhorn2007 Collaborative Encounters. In Collaboration in Archaeologi-

cal Practice: Engaging Descendant Communities, edited byChip Colwell-Chanthaphonh and T. J. Ferguson, pp.273–298. AltaMira, Lanham, Maryland.

Silliman, S.W.2008 Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in

Indigenous Archaeology. University of Arizona Press, Tuscon.

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

29September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

¡LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY FOR LATIN AMERICA!

Fellow Latin Americanists,

On behalf of the SAA Committee on the Americas, I write to request your support in broadening the distribution ofthe Society’s flagship journal for the region, Latin American Antiquity. If we can get the journal into more institutionallibraries throughout Latin America, articles will find wider, more appropriately inclusive audiences. At the same time,more of our colleagues will be inspired to submit to the journal and to consider joining the SAA themselves.

COA asks that you consider funding a gift subscription to Latin American Antiquity for a library at an institution withwhich you and/or your Latin American colleagues have a close relationship, or in a country or region in which youcarry out your research. When you identify a library that you would like to support, you should write to them to deter-mine whether or not they already receive LAA; if not, you will need the correct snail mail address for delivery. A giftsubscription for Latin America costs US$65 per year and your commitment would be one year at a time.

To order a gift subscription, please contact the SAA office at 1-202-789-8200 x109 or email [email protected] formore information.

Thank you for considering this opportunity to continue strengthening the intra-hemispheric relations that are soessential to American archaeology and so rewarding both personally and professionally.

—Dan Sandweiss, Committee on the Americas Advisory Network member

30 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

What does research on tangible and intangible her-itage look like when done in collaboration withdescendent communities— especially when they

take a leading role? How does a more equitable decision-making process contribute to archaeological practices thatare relevant, responsible, and mutually satisfying? And howcan ensuring that communities benefit from research ontheir heritage improve their relations with archaeologistsand heritage managers? These questions are currently beingexplored in the course of a seven-year international projecton Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage(IPinCH), based at Simon Fraser University. This initiativebrings together over 50 anthropologists, archaeologists,lawyers, ethicists, heritage and museum specialists withpartners from 25 communities and organizations to exploreintellectual property-related issues emerging within therealm of cultural heritage and their implications for theory,policy, and practice (www.sfu.ca/ipinch). We are supportedby a major grant from Canada’s Social Science and Human-ities Research Council.

Descendant communities, archaeologists, and other stake-holders are today confronted by a sometimes bewildering setof challenges regarding the appropriate use of culturalimages and designs; protocols for bioarchaeologicalresearch; fair and appropriate access to archaeological data,museum records, and other archives; cultural tourism andcommodification issues; changing legal interpretations ofcultural rights; and international heritage protection effortsthat purport to incorporate local conceptions of heritage— toname just a few key topics. IPinCH aims to document andlearn from the diversity of principles, perspectives, andresponses that emerge from these and other contexts dealingwith intangible aspects of heritage, and from this to compileand share examples of good practice and other resources. Weapproach these goals through three complementary compo-nents: (a) collaborative, community-based research initia-tives (discussed here); (b) an online library to compile anddistribute research materials, publications, and protocols;and (c) nine thematic Working Groups exploring the theo-retical, practical, ethical, and policy implications of intellec-

tual property. Throughout IPinCH we ascribe to a criticaltheory approach that seeks to foster positive change in thelives of participants— including researchers, altering courseas the research process proceeds based on feedback andongoing critical reflection on intellectual property issues incultural heritage.

IPinCH Case Studies

Our project has tried to take a ground-up approach by utiliz-ing a community-based participatory research methodology(see Atalay 2012; Nicholas et al. 2011). We have been able toprovide support for 11 community-based studies, now at dif-ferent levels of completion, situated within Indigenous com-munities in Canada, the United States, Australia, NewZealand, and Kyrgyzstan. Each study begins with the com-munity partner identifying issues of concern and then col-laborating as a co-developer with one or more IPinCH teammembers to propose a research design and budget. Researchmethods may include focus groups, community surveys,archival research, interviews with elders, or other informa-tion-gathering activities. Such an approach prioritizes com-munity needs, while also fostering relationships that addressat least some of the long-standing issues surrounding aca-demic research relating to mistrust, unequal power, and lossof control over the process and products of research. Oncethe study is complete, research products and data arereviewed at the community level to determine what infor-mation can be released to the IPinCH team to inform vari-ous meta-level research questions. Community retentionand control of the raw data ensures another layer of protec-tion for sensitive information or privileged knowledge. Eachcase study undergoes multiple layers of ethics review— at thecommunity level, within the home institutions of academicresearchers, and at Simon Fraser University.

What is the nature of these case studies and what they aretargeting? Here are five examples.

How can we best collect and pass on knowledge about our landand lifeways for use in guiding future development policies and

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

COLLABORATIVE, COMMUNITY-BASED HERITAGE RESEARCH, AND THE IPINCH

PROJECTGeorge Nicholas and the IPinCH Collective

George Nicholas is Director, Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage Project and Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University.

31September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

decisions? The “Moriori Cultural Database, Chatham Islands,New Zealand” study was developed by Susan Thorpe andMaui Solomon from Te Keke Tura Moriori (Moriori IdentityTrust), in affiliation with the Hokotehi Moriori Trust andKotuku Consultancy. Their initiative has established a Mori-ori cultural knowledge database to record traditional knowl-edge and protect IP through appropriate protocols, and alsocontributed to a youth-focused Hokotehi mentorship pro-gram on knowledge recording and archaeological methods.Both initiatives contribute to management strategies anddevelopment decisions that protect Moriori land and cultur-al heritage (Figure 1).

How do we protect, care for, and manage the sacred knowledgeembodied in ancestral sites while also sharing their lessons in cul-turally appropriate ways with the public? This question is at thecenter of “Education, Protection and Management of ezhibi-igaadek asin (Sanilac Petroglyph Site), Michigan.” Sonya Ata-lay (UMass-Amherst) with Shannon Martin and WilliamJohnson of the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture &Lifeways of the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michiganare working to determine culturally appropriate ways of pro-viding educational information about a petroglyph site con-taining over a hundred indigenous teachings to diverse pub-lic audiences while at the same time protecting the knowl-edge and images from inappropriate use. The goal is to uti-lize Anishinabe values and advice from spiritual leaders innegotiations with Michigan State agencies. The SaginawChippewa are again gathering at ezhibiigaadek asin for cere-monies but at this time still must have a state employee

unlock the protective fence that presently surrounds the pet-roglyphs (Figure 2).

What guidelines should apply to knowledge produced from ana-lyzing ancestral remains? “The Journey Home: GuidingIntangible Knowledge Production in the Analysis of Ances-tral Remains, British Columbia” is an initiative being collab-oratively developed by The University of British ColumbiaLaboratory of Archaeology (LOA) and the Stó:lo Researchand Resource Management Centre (on behalf of the Stó:loNation/Tribal Council). Susan Rowley (LOA), David Schaepeand Sonny McHalsie (both with SRRMC) are working withcultural advisers from the Stó:lo House of Respect Care-tak-ing Committee to develop protocols for how to make deci-sions about the study of human remains. For the Stó:lo,knowing as much as possible about these ancestors informstheir approach to repatriation and guides inquiry into multi-ple issues of scientific process, knowledge production, andintellectual property. The project aims to develop guidelinesand protocols for repatriation and analysis of First Nationancestral remains. These models may then be adopted byother groups as appropriate.

How do we assure the protection and inclusion of our own cul-tural principles and ways of knowing in government consulta-tions affecting our heritage? The “Yukon First Nation HeritageValues and Heritage Resource Management” study wasdeveloped by Sheila Greer, Catherine Bell, and Partners

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 1. Young Chatham Islanders Jade Lomano and son Solomonalongside a rakau momori (tree carving), which Moriori believe to bethe embodiment of ancestors. Photograph courtesy of Susan Thorpe.Photograph by Robin Atherton.

Figure 2. Members of the Saginaw Chippewa tribe hold regular cere-monies at Ezhibiigaadek asin, the Sanilac petroglyphs, but do not havea key to the protective fence surrounding the site. Photo courtesy ofStephen Loring.

32 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

Champagne & Aishihik First Nations (CAFN) Heritage, Car-cross-Tagish First Nation Heritage, and Ta’an Kwach’änCouncil. This study asks what heritage management basedon Yukon First Nations (YFN) values looks like in order toimprove their ability to fulfill their rights and obligations asestablished under their respective Land Claim and Self-Gov-ernment Agreements. Community-based ethnographicresearch is being used to identify these values and how theycompare to those expressed in western heritage resourcemanagement concepts and practices. The team is also exam-ining how Yukon Indian values can reframe approaches tothe management of the heritage resources by self-governingYFNs under their respective land claims.

How do we establish protocols for outsiders who work with cul-turally sensitive sites or information? “Developing Policies andProtocols for the Culturally Sensitive Intellectual Propertiesof the Penobscot Nation of Maine” was developed by BonnieNewsom (Penobscot Nation), Martin Wobst and Julie Woods(both with UMass-Amherst). Here the goal is to combine thetribal community voice and knowledge with ethnographic,archaeological and legal information to create policies, pro-cedures and protocols that protect Penobscot intellectualproperty associated with their cultural landscape, whilemaintaining compliance with state and federal historicpreservation and cultural resource management laws andregulations. Included in this plan are Intellectual Property(IP) and cultural sensitivity training workshops for outsidearchaeologists and researchers. The Penobscot Nation hasestablished a community-based Intellectual Property (IP)working group to identify aspects of their heritage that areparticularly sensitive. The working group is also creating aformalized tribal structure to address IP and other research-related issues.

Other IPinCH-funded projects are “Cultural Tourism inNunavik” (Nunavut, Canada) led by Daniel Gendron and theAvataq Cultural Institute; “Secwepemc Territorial Authority:Honoring Ownership of Tangible / Intangible Culture”(British Columbia, Canada), developed by Brian Noble (Dal-housie U.) and Arthur Manual (Secwepemcul’w); and“Grassroots Resource Preservation and Management in Kyr-gyzstan: Ethnicity, Nationalism and Heritage on a HumanScale” (Kyrgyzstan), led by Anne Pyburn (Indiana U.) andKrygyz colleagues. Two other IPinCH case studies—Inu-vialuit and Ngaut Ngaut—are reported on in this issue. In allof these studies, the incentive has come from the communi-ty, they develop and direct the study, and they are the primarybeneficiaries. Benefits also flow to IPinCH researchers andteam members, and from them to other academics, descen-dant communities, policy makers, and the public at large.

What We Are Learning

Collaborative research has the potential to reveal important

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

insights into the different value systems relating to “her-itage,” which can contribute to successful heritage manage-ment, especially when coupled with an ethnographicapproach (Hollowell and Nicholas 2009).

At the same time, we have found that the process of collabo-rative research can be as illuminating as what it produces.For example, we continue to learn from our community part-ners about the intrusive nature of research; they see this asan opportunity to teach us how to conduct research in arespectful manner. Constant critical reflection and willing-ness to respond constructively to critique are thus requisite.

Beyond the anticipated results of each case study, other bene-fits accrue with IPinCH partners coming together, findingsupport for the challenges they face (e.g., archaeotourism)and launching initiatives of their own. These may includesymposia and workshops on, for example, commodificationof the past, which are designed to meet the needs of commu-nity partners affected by loss of control over their heritage.

There are considerable challenges to collaborative research(Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson 2008). It requiresconsiderable time and effort, even where participants arebuilding on relationships previously developed between thecommunity and one or more team members. Things takelonger than expected, and there are unavoidable and unan-ticipated delays. And because the outcome may be uncertain,such research can be particularly risky for untenured schol-ars and graduate students. Finally, some of the biggest chal-lenges our projects have faced involve the time and energyrequired to work with multiple institutions— often transnationally— to get funds flowing and ethics reviewscompleted. In some instances we have to have three separateethics reviews for a single study. We have found that univer-sity financial officers and IRBs need and want to be educat-ed about community-based research, which is generallyunlike anything they have dealt with before— the same holdstrue for most archaeologists, who have not had to prepare anethics application.

Conclusions

If we hope to comprehend the nature and impact of heritage-related issues upon people’s lives, it makes sense to see howthese play out on the ground, rather than limit this just todiscourse between scholars. We also need ensure that bene-fits flow both ways between community partners and aca-demic researchers. A deeper understanding of what is atstake will promote research relationships that are more equi-table, responsible, and accountable. This can only be done byworking collaboratively with descendant communities.

>NICHOLAS, continued on page 35

33September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

This paper details a collaborative endeavor betweenFlinders University archaeologist, Amy Roberts, andthe Mannum Aboriginal Community Association Inc.

(hereafter MACAI). Together Roberts and MACAI began aninterpretive project for a significant site known as NgautNgaut to the Aboriginal community (named after an ances-tral being). However, this place is invariably referred to asDevon Downs in archaeological textbooks. Indeed, one of theaims of the Ngaut Ngaut Interpretive Project has been toreinstate the traditional toponym in broader literature. Thisstep is seen as just one way in which Indigenous peoples cancounter colonialism.

Located on the Murray River in South Australia this rock-shelter site was the first in Australia to be “scientifically”excavated. The excavations, conducted by Norman Tindaleand Herbert Hale, began in 1929 (Hale and Tindale 1930).Their research provided the first clear evidence for the long-term presence of Indigenous Australians in one place (Fig-ure 1).

Prior to Hale and Tindale’s excavations little systematicresearch had been conducted in the field of Indigenous Aus-tralian archaeology. In fact, the thinking of the day was thatIndigenous Australians were recent arrivals to Australia andconsequently it was generally believed that the material cul-ture of Indigenous Australians had not changed over time.Hence, the research at Ngaut Ngaut provided a turning pointin the way the Indigenous Australian archaeological recordwas viewed.

The impetus for the Ngaut Ngaut Interpretive Project arosewhen Roberts was working as an “expert” anthropologist onnative title issues in the region in 2007 and visited the sitewith MACAI representatives (although she had worked withthe community since 1998). During subsequent discussions,it became clear that MACAI’s cultural tourism operationswere being hampered due to the fact that the Director ofNational Parks and Wildlife had closed parts of the site as aresult of riverbank erosion during the recent and severedrought suffered in many parts of the country. As a result,

MACAI were in need of interpretive materials that could beused during such times— and so began the collaborativejourney.

MACAI had originally requested that Roberts provide photo-graphic images they could use during park closures. Howev-er, as discussions developed it became clear that togetherRoberts and MACAI could create a suite of interpretive mate-rials (for both off and on-site purposes) that would benefit thecommunity’s cultural tourism ventures as well as their aspi-rations to educate the public about Aboriginal culture and tofoster greater cross-cultural understandings (Figure 2). Fund-ing was obtained for Stage 1 of the project (from the Aborig-inal Affairs and Reconciliation Division in South Australia)and interpretive signs, educational posters (to be used duringclosures) and brochures were produced.

The content of the signs, posters, and brochures specificallyincorporated the many tangible and intangible aspects andvalues of this significant place. It was important for MACAIthat both tangible and intangible values relating to the sitewere addressed in the interpretive content. Indeed, whilstMACAI value the site’s archaeological history and the physi-cal evidence of the excavations, they also wanted the site’scultural importance to be presented to the public. In partic-ular, they wanted to present to the public some of the cultur-al complexities relating to Ngaut Ngaut and to redress thestandard, one-dimensional and arguably colonial archaeo-logical story that exists in Australian textbooks.

Some of the many intangible values attached to the site thatrequired interpretation included: rock art interpretations andcultural meanings, “Dreamings,” oral histories, discussionsabout Aboriginal group boundaries, “totemic” issues and“bushtucker” knowledge (see also Roberts et al. 2010). Thefunding obtained for Stage 1 also allowed for the employ-ment of a local artist to provide paintings to be used in theinterpretive materials to enhance some of the areas listedabove. Similarly, MACAI were engaged to produce the signframes rather than contracting the work out to a non-Indige-nous company. Indeed, throughout the project Roberts and

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

THE NGAUT NGAUT INTERPRETIVE PROJECTCOLLABORATION AND MUTUALLY BENEFICIAL OUTCOMES

Amy Roberts and Isobelle Campbell

Amy Roberts is an archaeologist at the Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia and

Isobelle Campbell is the Chairperson of the Mannum Aboriginal Community Association Inc.

34 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

MACAI worked to create additional community benefits asfurther outlined below.

Throughout Stage 1 of the project it became apparent thatMACAI were becoming increasingly concerned about prob-lematic online webpages about Ngaut Ngaut such as:

1. Brief, unfocused and/or inaccurate information on Stategovernment and/or tourism websites. For example, tour -ism websites often only highlight one or two values relat-ing to the site and this information tends to be replicated.State government websites primarily discuss risk man-agement issues or where detail is included (e.g., in man-agement plans) some of this information is inaccurate(e.g., incorrect dates have been reported for the site) andagain only certain aspects of the site are emphasised; or

2. Inaccurate and/or offensive information— generally bloggedby tourists who have visited the site or websites that useimages of the site and then claim copyright over them.

As a result of these concerns, and through discussions withGeorge Nicholas and the IPinCH (Intellectual PropertyIssues in Cultural Heritage) group, a second stage of theproject was devised and funded.

Stage 2 has seen the development and near completion ofan online interpretive book (to be hosted by the South Aus-tralian Department of Environment and Natural Resources)as well as a hard copy version, which will be published byIPinCH. Indeed, prior to the prevalence of the InternetMACAI were able to control the content shared with visitorsto Ngaut Ngaut. However, the Internet now poses signifi-cant challenges to the presentation and regulation of cultur-al information, site images and copyright issues. As suchthe key differences between the IPinCH-funded work andother Internet resources is that the materials have beendeveloped in a collaborative, structured and culturally sus-tainable manner.

However, as was the case with Stage 1 of the project, addi-tional community benefits were incorporated into the Stage2 funding. For example, funding was obtained throughIPinCH for MACAI representatives to attend internationaland national conferences/symposia to talk about the NgautNgaut Interpretive Project and to learn from their interna-tional and national Indigenous counterparts as well as fromother archaeological projects and practitioners (Figure 3).

Similarly, funds were used to enable MACAI members tovisit the excavated Ngaut Ngaut collection, which is current-ly housed at the South Australian Museum. This visit provedto be a significant and emotional event for the communitymembers who attended and excerpts from the interviewsconducted afterwards have been incorporated into the onlineinterpretive materials (Figure 4). Proceeds from the sale ofthe hard copy version of the book will also be fed back into

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 1 The cliffs at Ngaut Ngaut. Photograph by Amy Roberts.

Figure 2 Isobelle Campbell (MACAI chairperson) (left) talking aboutone of the interpretive signs at Ngaut Ngaut. Photograph by AmyRoberts.

Figure 3 L-R: Isobelle Campbell and Amy Roberts presenting a paper atthe 2011 IPinCH conference in Vancouver. Photograph courtesy ofIPinCH.

35September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

MACAI community initiatives and their management activ-ities at Ngaut Ngaut.

Given that the Ngaut Ngaut Interpretive Project has trulybeen a jointly conducted initiative it is situated at the pro-gressive end of what Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson(2007) describe as the “collaborative continuum.” While sucha collaborative undertaking requires a significant investmentof time and energy (see Nicholas et al. 2011 for additionaldiscussion) for both researchers and communities, this doesnot mean that such projects cannot be mutually beneficial.Indeed, as is clear in the discussion above all stages of theNgaut Ngaut Interpretive Project were designed to includeadditional community benefits (above and beyond thoserelating to the central tenets of the project). Similarly,Roberts has also furthered her career as a researcher and aca-demic by being able to publish various articles and a forth-coming book (often coauthored with MACAI or members ofMACAI). However, Roberts and her home institution(Flinders University) have also benefited in other ways thatshould also be acknowledged— e.g., with MACAI approvinggraduate-level student projects on various aspects of theNgaut Ngaut collection and by hosting field schools at thesite. Indeed, university programs in Australia are nowdependent on Indigenous communities to provide suchapprovals and their collaboration/participation in these pro-grams needs to be accorded due recognition.

References CitedColwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, and T. J. Ferguson

2007 Introduction: The Collaborative Continuum. In Collabora-tion in Archaeological Practice: Engaging Descendant Com-munities, edited by Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh and T. J.Ferguson, pp. 1–32. AltaMira, Lanham, MD.

Hale, Herbert, and Norman B. Tindale1930 Notes on Some Human Remains in the Lower Murray

Valley, South Australia. Records of the South AustralianMuseum 4:145–218.

Nicholas, George P., Amy Roberts, David M. Schaepe, Joe Watkins,Lyn Leader-Elliot, and Susan Rowley

2011 A Consideration of Theory, Principles and Practice in Col-laborative Archaeology. Archaeological Review from Cam-bridge 26(2):11–30.

Roberts, Amy L., Mannum Aboriginal Community Association Inc.and van Wessem, A.

2010 The Ngaut Ngaut (Devon Downs) Interpretive Project –Presenting Archaeological History to the Public. Aus-tralian Archaeological Association Conference, BatemansBay, 9-13 December 2010. Electronic document,http://www.australianarchaeologicalassociation.com.au/poster_gallery.

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 4 L-R: Isobelle Campbell, Anita Hunter and Ivy Campbellinspecting the excavated Ngaut Ngaut collection at the South Aus-tralian Museum. Photograph by Amy Roberts and courtesy of the SouthAustralian Museum.

References CitedAtalay, Sonya

2012 Community Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and forIndigenous and Local Communities. University of CaliforniaPress, Berkeley.

Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, and T.J. Ferguson (editors)2007 Collaboration in Archaeological Practice: Engaging Descen-

dant Communities. AltaMira Press, Lanham, Maryland.Hollowell, Julie J., and George P. Nicholas

2009 Using Ethnographic Methods to Articulate Community-Based Conceptions of Cultural Heritage Management.Public Archaeology 8(2/3): 141–160.

Nicholas, George P., Amy Roberts, David M. Schaepe, Joe Walkins,Lyn Leader-Elliot, and Susan Rowley

2011 A Consideration of Theory, Principles and Practice in Col-laborative Archaeology. Archaeological Review from Cam-bridge 26(2):11–30.

NICHOLAS, from page 32 <

36 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

Since 2006, the Iringa Region Archaeological Project(IRAP) has been conducting field research on the richarchaeological and historic heritage of Iringa. IRAP is

a rapidly growing team, composed of academics,researchers, and graduate students in Canada, the U.S., Eng-land, Australia, and Tanzania. The main goal is to investigatethe Upper Pleistocene and later history, in relation to modelsof the African origins of Homo sapiens. Before our teamarrives in Tanzania, extensive preparations are requiredincluding applying for research clearance from COSTECH(The Tanzanian Commission on Science and Technology).This is required for all participants, i.e., any individual whowill be a part of our team regardless of nationality or posi-tion. We also notify the Director of the Division of Antiqui-ties, Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, Govern-ment of Tanzania, of our intent to apply for COSTECH clear-ance. This is because Antiquities will review our file and pro-vide our excavation license. Without COSTECH clearancewe could not receive an excavation license and we will notreceive COSTECH clearance without the approval of Antiq-uities, the division responsible for historic resources on themainland of Tanzania. One of the requirements for receivingCOSTECH clearance is that foreign researchers must workwith a local collaborator, a Tanzanian national who “vouches”for the quality of your research and your character. Thisprocess of acquiring appropriate legal permissions to con-duct archaeological fieldwork therefore necessitates success-ful (i.e., ethical and cordial) collaboration with local archae-ologists, academics, and professionals. Once these two per-mits have been obtained we are assigned an Antiquities Offi-cer who will accompany us for the duration of our field sea-son and observe all aspects of our research.

Our official duties and obligations continue upon our arrivalin the field research area. We spend days greeting local offi-cials from every branch of government and within everycommunity we visit to introduce ourselves and to explain ourreasons for conducting research in their jurisdiction. At anytime we could encounter resistance to our research and findourselves unwelcome; our acute awareness of the distrustand suspicion faced by foreign researchers was one of the

main motivations behind developing a research programfocused on communication and local collaboration.

Prior to IRAP’s investigations, little archaeological researchhad been undertaken in this region. In 2006, preliminarytest excavations were undertaken at two rockshelters: Magu-bike and Mlambalasi. The purpose of this preliminary studywas to determine the archaeological potential, artifact densi-ty, and stratification of rockshelter sites in the region (Biit-tner et al. 2007). Mlambalasi rockshelter is located next to theburial site of the nineteenth-century Uhehe Chief Mkwawa,a leader in the resistance against German colonial forces,and as such the site has important cultural and historic sig-nificance. Magubike rockshelter is located adjacent to the vil-lage from which the name is derived. Consequently, manylocal people visited the site on a daily basis while we wereworking and expressed a vested interest in what we weredoing on their land and with their resources. Although fromour perspective the field season was very productive andrewarding, it was clear that local communities had concernsabout our presence and our motives.

In 2008, IRAP returned to undertake a large-scale regionalsurvey documenting the distribution of sites and stone rawmaterial sources. Surface materials were collected at 12 loca-tions, including a number of previously unrecorded archae-ological and heritage sites. Test excavation at Magubike rock-shelter was continued to determine the extent of the archae-ological deposits.

It was another successful field season but not just because ofwhat we accomplished archaeologically. 2008 was the firsttime we brought along posters for distribution at local officesand museums. The posters were prepared in both Englishand Swahili, and described our research. Small handoutswere also prepared of the posters to give out everywhere— offices, schools, museums, churches, and to anyone whoasked who we were and what we were doing. The receptionwas astounding. We repeatedly heard comments like “manyforeigner researchers promised to bring back the informa-tion they learned from working on our land, you are the first

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

WORKING WITH LOCAL COMMUNITIES ANDMANAGING CULTURAL HERITAGE IN IRINGA

REGION, TANZANIAKatie M. Biittner and Pamela R. Willoughby

Katie M. Biittner and Pamela R. Willoughby are with the Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

37September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

to actually do so.” Magubike village called a meeting andinvited us to attend. At this meeting they indicated that theyhad previously been skeptical of what we were doing andwhy, but after taking the time to read the poster they nowunderstood. We were formally invited to continue our workat the site and asked to continue to share our informationwith them. Many people commented on how they recog-nized us and our names from the posters. These postersmarked our first huge step in earning the trust of the com-munities with which we hoped to collaborate.

We returned in 2010 for more fieldwork and brought moreposters. This time we created three posters: a regional onesimilar to that distributed in 2008 (Figure 1), an East Africanculture history overview (Figure 2), and one focused entirelyon Magubike rockshelter (Figure 3). The East African CultureHistory poster was developed after recognizing that we wereusing terminology with which many local people were unfa-miliar. We prepared this instructional tool particularly for thesecondary school in Magubike, using images taken of arti-facts, fossils, and skeletal specimens at the University ofAlberta, photographs taken by Biittner of sites, or open sourcematerials. We focused on Magubike rockshelter for anotherposter to continue to build a trusting and collaborative rela-tionship with the village of Magubike. The poster emphasizedthe importance of Magubike rockshelter from the perspective

of human evolution, East African culture history, and, for thefirst time, cultural heritage management. The school children,in particular, were so excited by this poster of “their site.” Atthe ceremony where we handed over these posters to theschool, the headmistress, teachers, and students all spokeabout the sense of pride they all felt knowing they had such animportant part of human heritage in their backyard.

From Posters to Management: Cultural Heritage inIringa Research Program (CHIRP)

The posters have proved to be only one small, but important,step in engaging local communities. Since we began ourposter “campaign” we have been approached by various com-munity members and groups asking for support and assis-tance in education and economic development. Ourresponse to this request was to form the Cultural Heritage inIringa Research Program (CHIRP). CHIRP is a long-termprogram which will involve the direct engagement of localcommunities using interviews, public meetings, and work-shops at schools in the region towards the collective and col-laborative management of cultural heritage.

Through CHIRP we intend to:

1. provide support to local archaeologists, cultural, and

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 1: “The Archaeological Heritage of Iringa Region, Tanzania” poster distributed throughout Iringa region and on display in local schools, offices,museums, hotels, and restaurants.

38 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

antiquities officers (including access to resources for thedevelopment of professional and conservation skills);

2. improve public awareness regarding conservation ofmovable and immovable cultural resources;

3. educate and work with local communities in fields relat-ed to cultural heritage and cultural tourism;

4. work with local communities in developing, document-ing, and presenting their own local histories; and

5. work with educators to develop relevant curriculum con-necting local archaeology with key events in human evo-lution.

We will continue to prepare and provide posters based oninformation generated from both consultation with localpeoples and the result of our ongoing archaeologicalresearch projects. We hope to expand our translationsbeyond English and Swahili to include local, threatened lan-guages like Kihehe.

As Magubike rockshelter is located so close to the secondary

school (you can see it from the classroom), it provides anexcellent opportunity to give students hands on experiencedoing archaeology including laboratory analysis and inter-pretation. This means the people who have a vested interestin the information produced by our research will play adirect role in constructing the narrative (what does it mean,what are the implications of our findings) and in dissemi-nating the results. We hope to work closely with local peopleto find more culturally relevant or appropriate ways of dis-seminating our results. Illiteracy is an issue in Iringa, whichmeans our posters are not the best long term solution foroutreach. We must make all aspects of our research and ourdiscipline accessible.

In the long term we will continue to document the historicand archaeological potential of Iringa, to improve conditionson heritage sites and in collections, and to alleviate povertyby supporting the cultural tourism industry in Iringa. Bypartnering with local artisans and tour operators, we canhelp to bring money into the local economy. A number ofMagubike villagers commented that they could not under-stand why, if the sites in Iringa are so important, tourists are

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 2: “East African Culture History” poster prepared as an instructional tool for the secondary school at Magubike village.

39September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

not flocking to Iringa as they do to Arusha (the starting pointfor safaris to Olduvai and the Serengeti). Much of the dam-age to existing sites across Tanzania can be attributed topoverty. Local villagers now regularly report looting activitystating that they understand the intellectual and culturalvalue of sites and their potential to draw tourists to theregion because of our posters. Our posters are only thebeginning of what we hope will be a successful outreach pro-gram to engage local people.

Acknowledgments: Pamela Willoughby’s IRAP research hasbeen supported by the Social Sciences and HumanitiesResearch Council of Canada (SSHRC), by a Post-PhDresearch grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation and by aKillam Research Grant from the Vice-President (Research),University of Alberta. Katie Biittner’s research has beenfunded by a Doctoral Fellowship from SSHRC, and by a Dis-

sertation Fellowship from the Faculty of Graduate Studiesand Research, University of Alberta. We thank COSTECHand the Division of Antiquities, Government of Tanzania,and the people of the villages of Magubike, Kalenga, Wenda,Lupalama, Kibebe, and Iringa town for their continued sup-port of both IRAP and CHIRP. Finally, we would like tothank our IRAP team members Pastory Bushozi, BenCollins, Katherine Alexander, Jennifer Miller, Elizabeth Saw-chuk, Frank Masele, Chris Stringer, and Anne Skinner fortheir ongoing contributions to the project. Asante sana.

References CitedBiittner, Katie M., P.M. Bushozi, and Pam Willoughby

2007 The Middle Stone Age of Iringa Region, Tanzania. NyameAkuma 68:62–73.

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 3: In response to concerns expressed by villagers of Magubike village, we prepared a poster highlighting the archaeological significance of theirrockshelter.

40 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

Our project concerns the tiny, remote island of Tiga,smallest of the inhabited islands in New Caledonia’sLoyalty Islands. New Caledonia is a largely

autonomous French territory some 1,200 kilometers off thenortheast coast of Australia (Figure 1). The territory’s mainisland, Grande Terre, is geologically complex, while the Loy-alties, which lie east of Grande Terre, are simple raised coralreefs. New Caledonia’s indigenous people call themselvesKanaks. Today, they share the islands with a substantialnumber of settlers of European, Asian (primarily Viet-namese) and Polynesian background, virtually all of whomlive in and around the capital, Nouméa. Apart from one expa-triate European family running the primary school and onelong-term resident from Tahiti, Tiga’s permanent populationof around 150 is entirely Kanak. There is no tourism and nocommercial industry. People live by gardening, fishing, andhunting. Most people of Tigan descent live elsewhere, main-ly on the neighboring and very much larger islands of Maréand Lifou in the Loyalties, or in Nouméa.

Our work on Tiga includes local archaeologists and oral his-torians of Kanak, European and Asian descent as well as col-leagues of European descent from metropolitan France andAustralia. We communicate with the local community inFrench, which is New Caledonia’s lingua franca, as well aslocal island languages. We have been exploring the limits of‘translatability’ of archaeological objectives and findings onthe one hand and local conceptions of history on the other.We have found that we can mesh certain details of both in away that works for archaeologists as well as local people. Indoing so, we have come to realize that commonalities of per-ception on a higher plane of abstraction are ultimately moreimportant to this process than lining up precise details.

Archaeologically speaking, the project was motivated by thefact that New Caledonia is unique in Pacific prehistory. Thefounding human occupation some three thousand years agooccurred as part of the dispersal of the well-described Lapita

cultural complex, but differed in several critical respectsfrom elsewhere in the Lapita distribution. Subsequent tra-jectories of change produced levels of cultural diversificationunparalleled further East in Remote Oceania, the vast regionbeyond the main Solomon Islands chain. The problem forarchaeologists is that their interpretations of New Caledo-nia’s dynamic human history conflict with local Kanak views.The latter are largely either versions of or a reaction to syn-chronic historical and ethnographic pictures developedbefore modern archaeology started in the region. These lat-ter scenarios paint “traditional” Kanak society as a small-scale and semi-nomadic one governed through petty chief-doms. Such descriptions have been completely underminedby the archaeological demonstration that the last millenni-um before European contact was characterized by a denselyinhabited landscape of labor-intensive horticulture organ-ized by strong chiefdoms, which collapsed as a result of pro-found demographic and cultural disruption between initialEuropean contact in 1774 and the French takeover in the1850s.

This dramatic archaeological reappraisal of “traditionalKanak culture” deeply unsettles many indigenous New Cale-donians as well as the expatriate scholars who promoted pre-archaeological views. These sentiments also are felt in rela-tion to the archaeological demonstration that there weremajor cultural shifts in the archipelago during the precedingthree millennia of human activity. On this basis, exactly whatarchaeology is “for” in New Caledonia remains as unclear tomost Kanak, as it does to many other indigenous peoplearound the world. In reaction to attempts by settlers to char-acterize Kanaks as just another group of migrants who haveno more claim to land and cultural rights than any othergroup in the modern population, Kanak activists and theirEuropean sympathizers have attacked the entire concept ofhistory and long-term cultural change as a tool of neocolo-nial oppression. As in many other settler societies, activistspromote a two-step model in which a static precolonial

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH IN NEW CALEDONIA

Ian Lilley, Christophe Sand, and Frederique Valentin

Ian Lilley may be reached at the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit, University of Queensland 4072, Australia. Christophe Sand may

be reached at the Institut d’Archéologie de la Nouvelle-Calédonie et du Pacifique, Nouméa, Nouvelle-Calédonie. Frederique Valentin may be reached at

the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UMR 7041, Maison de l’archéologie et de l’ethnologie, René Ginouvès, Nanterre, France.

41September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

“Golden Age” was destroyed by Western colonization. In thisscenario, the population of New Caledonia is polarized as“indigenous” or “invaders.” This division emerged in the late1970s. It led to a major political emergency, including peri-ods of undeclared civil war in the 1980s, the after-effects ofwhich have not entirely dissipated and make archaeologyimpossible in a few places.

So, what have we done on Tiga against this backdrop? Overfour major seasons of fieldwork as well as several shorter vis-its we have explored a significant part of the island includingsome of its many caves, and mapped and test-excavated anumber of sites from different periods in the island’s histo-ry back to an initial Lapita settlement. Before the start of thearchaeological fieldwork, the team’s Kanak oral historianrecorded oral histories and mythological traditions in greatdetail. The archaeological survey started with the recordingof the sites that the local clans considered important in theirhistory, without any consideration for their archaeologicalsignificance. Although analysis is not complete, we havedelineated a sequence of occupation that charts the move-ment of the population from an initial beach occupation inLapita times up onto the higher parts of the island wherenearly the entire population lived until European contactwhen missionaries encouraged people to move back down tothe beach area where nearly everyone lives today. We have

demonstrated significant expansions in habitation and sub-sistence gardening on the raised parts of the island duringthe first and second millennium AD. This expansion extend-ed into very rugged and difficult peripheral areas, in whichliving and working would have required great effort. Thisintensification suggests that there was a period of populationand subsistence stress on the island, as there was elsewherein New Caledonia at this time. Perhaps the most intriguingthing we have found is that people on Tiga overcame a com-plete lack of surface water by creating imaginative and high-ly effective water catchment systems in the island’s manycaves (Figure 2).

We have been attempting to integrate these archaeologicalfindings with oral tradition and myth to produce long-termhistory that makes sense to local people and us alike. Whilethere is certainly a reflective, theoretical dimension to ourwork, our primary interest is quite pragmatic: to get localpeople to engage with archaeology in whatever way bestworks for them. Rather than try to match specific archaeo-logical and oral-historical/mythological details, which in ourexperience frequently bogs down in Melanesia in irreconcil-able differences of opinion, we have chosen to meld ourresults with local historical perspectives on a more abstract,thematic level, emphasizing the sweep of history and theclasses of events and processes within which the archaeolog-ical nitty-gritty is situated. Archaeological details are thusstill crucial, providing the “beef” as it were, but they areframed in a larger context of meaning which better reflectsthe shared ‘meta-interests’ of locals and archaeologists. Suchmeta-interests are captured well by Tim Ingold (2000:189),who, quoting Adams, recognizes that “for both the archaeol-ogist and the native dweller, the landscape tells— or rather

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 1. Location map of Tiga Island, Loyalty Islands Province, NewCaledonia (showing selected sites not discussed in the text).

Figure 2. Artificial subterranean water-harvesting feature, Tiga Island(Author’s (CS) hand and green torch for scale to left).

42 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

is— a story, ‘a chronicle of life and dwelling’ (Adam1998:54).” To put it simply, we have discovered that historicalparticulars do not need to match exactly to match effectively.We have found that archaeology and local narratives canagree, for instance, that certain broad types of activityoccurred, perhaps even in generically similar locations inroughly equivalent sequences. To use archaeological terms,on Tiga we have shared interest in the physical origins of theisland, for example, as well as in first colonization, the intro-duction of domesticates and other exotic fauna, variations inpopulation movement to the island and the shifting direc-tions of such movement.

We have been able to collate these shared interests togetherin our community publication, a tentative outline of which isshown in Figure 3 (Tokanod is the Maré word for Tiga). Thefirst chapter concerns Tiga’s physical origins, where werecount the story of a man raising the island from the sea byblowing a conch trumpet before we relate geological under-standings of the process, including the formation of themain beach area where first colonization occurred. Thatoccupation is then discussed. The second chapter considersthe movement to the plateau and the discovery or at least ini-tial major harvesting of subterranean water sources, intro-duced by a local story concerning the latter. The remainingchapters move through the archaeological sequence tying inmyth and oral history as appropriate, up to the “last chief-doms on the plateau” and the return to the beach in mis-sionary times. We are aware that much of the oral historyand myth is not sequential in the way we have ordered it toblend with the archaeology. We are also well aware that oncecommitted to print, such a sequential scheme may becomecemented as the traditional truth of things. We have done noharm to the traditions and stories themselves though, andTigans both on and off island are more than capable ofunderstanding what we have done and why. They are com-fortable with our approach and appreciate our efforts to“meet them halfway.” On that basis, we claim some successin helping them understand “what archaeology is for,” whichin turn we hope will help us win greater acceptance of andinterest in archaeology elsewhere in New Caledonia.

Acknowledgments. We thank the people of Tiga for theirfriendship and collaboration. David Baret and DanRosendahl produced Figure 1.

Reference CitedIngold, T.

2000 The Perception of the Environment. Routledge, London.

Les chercheurs d’eau : Mythes, histoires et archéologie de Tokanod

PréfaceIntroduction : contexteChapitre I. Premier peuplement – le souffleur de conque• Origine géologique de Tokanod• Mise en place de la dune• Première installation Lapita et ses caractéristiques

2500-2700 BP• Données de LTD018Chapitre II. La montée sur le plateau – les explorateurs

de l’eau• Données pédologiques et le gouano• Les plus anciennes datations des grottes 2100-2300

BP• Les données de Cholé et abri LTD076Chapitre III. L’humanisation du plateau – Siwen• La traversée des animaux (rat et poule sultane) 1000-

2000 BP• Transformations de la végétation• Les sites de plateau, en abri et en enclos, mise en

place de tas• Liens avec MaréChapitre IV. La côte est et les liens avec la Grande Terre

– histoire des Dawas• Les données de l’abri des Dawas (dates et peintures

murales) 1200-2000 BP• Données sur le plateau de la côte Est (zone sans

sépultures, très peu de coquillages)• Liens archéologiques avec le Grande Terre (poteries,

herminettes etc)Chapitre V. Conflits et évolutions sociales/environ-

nementales – Les deux géants• Changements environnementaux (dune, tectonique)• Densification des occupations (datations sites et enc-

los plus récents) <1500 BP• Cimetières étudiés• L’implantation des Kiamu XetiwaanChapitre VI. Les dernières chefferies du plateau - La

guerre de Ruet• Les données archéologiques (four du plateau, Cholé

etc) <500 BP – ethnographique• La chefferie d’Umewac et la division du plateau• La christianisation et l’histoire du maïs• La descente vers le bord de merConclusion. La nature du lien entre mythes, histoires et

archéologie ?ANNEXES. Textes en langue, mot à mot, traduction

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 3. Tentative contents of Tiga community publication, showingintegration of local and archaeological histories.

43September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

The Inuvialuit Living History Project was initiated inNovember 2009 with a visit by Inuvialuit communitymembers and non-Inuvialuit collaborators to the

Smithsonian Institution’s MacFarlane Collection: 300remarkably preserved ethnographic objects and nearly 5,000natural history specimens. These items were acquired byHudson’s Bay trader Roderick MacFarlane while running afur trade post among Anderson River Inuvialuit in the 1860s(Figure 1). Elders, youth, seamstresses, anthropologists,archaeologists, educators, and media specialists traveledfrom the Western Arctic and other locations across NorthAmerica to learn more about this ancestral collection, whichfew Inuvialuit or museum professionals have ever seen orstudied (Figure 2; Loring et al. 2010; Morrison 2006). TheMacFarlane Collection is not eligible for repatriation underNAGPRA because the Inuvialuit community resides inCanada, making alternative forms of access to the collectiona priority.

Our project seeks to generate and document Inuvialuit andcuratorial knowledge about the objects in the MacFarlaneCollection, with a wider view to sharing and disseminatingthis knowledge in the Inuvialuit, anthropological, and inter-ested public communities. We have conducted extensiveinterviews with Inuvialuit Elders and knowledgeable com-munity members, held workshops with Inuvialuit studentsand teachers in several Western Arctic communities, andcarried out material culture research on the objects in thecollection at the Smithsonian. These research activities haveculminated in our recently launched website––www.inuvialuitlivinghistory.ca––which brings together cura-torial descriptions of the collection, Inuvialuit knowledge ofobjects, media documenting our trip to the Smithsonian in2009, and subsequent community projects related to theobjects (Figure 3) (Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre2012). The website represents the MacFarlane Collection asa “Living Collection”––Inuvialuit Pitqusiit Inuuniarutait inInuvialuktun––because the project has spurred many Inu-

vialuit to begin discussing, re-creating, and using these his-toric objects in their everyday lives (Hennessy et al. 2012).

The Inuvialuit Living History Project has depended on col-laboration between team members, partners, and funders.We are particularly supported in our work by relationships toInuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre, the Smithsonian’s Arc-tic Studies Center, the Museums Assistance Program, ParksCanada, the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, theSchool of Interactive Arts and Technology and the Intellectu-al Property in Cultural Heritage (IPinCH) Project, bothhoused at Simon Fraser University. The present forum hascreated an opportunity for our team to collectively evaluatewhat processes and elements attend a successful collabora-tive research project, to identify the challenges that we con-tinue to face, and to assess the response to our project so far.To this end, we developed a series of general questions aboutour project and interviewed our project team members, whocomprise the authors of this paper. Below, we present a sum-mary of responses rather than individual quotations due tothe brevity of this article.

What do you think has made our project successful?

All of our team members noted the diverse strengths of indi-viduals as a main contributor to the success of our project.Our team came together with a shared interest to learn moreabout the MacFarlane Collection, particularly from an Inu-vialuit perspective, and to share this knowledge with thebroader Inuvialuit community. Our team members havebeen dedicated to this purpose, and have taught one anothera great deal about creating products and media that areappropriate, relevant, and interesting to the community(Lyons et al. 2011). While our team comes from different per-sonal and professional backgrounds, we have significantoverlap in skills and interests. These interests include com-munity-based heritage, digital repatriation, material cultureresearch, and anthropological and museum policy and prac-

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

THE INUVIALUIT LIVING HISTORY PROJECTNatasha Lyons, Kate Hennessy, Mervin Joe, Charles Arnold,

Stephen Loring, Albert Elias, and James Pokiak

Natasha Lyons is a Ph.D and Partner in Ursus Heritage Consulting; Kate Hennessy is an Assistant Professor in the School of Interactive Arts

and Technology, Simon Fraser University; Mervin Joe is an Inuvialuit Resource Management and Public Safety Specialist, Parks Canada;

Charles Arnold is an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary; Albert Elias is an Inuvialuit Elder and

professional interpreter; Stephen Loring is a Museum Anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution’s Arctic Studies Center;

James Pokiak is an Inuvialuit Elder and big-game hunting outfitter.

44 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

tice. Team members have provided access to their profes-sional and community social networks, knowledge of fund-ing opportunities, and technical resources. This combina-tion of knowledge, perspectives, skills and resources hasaided our work immeasurably, and allowed us all to do col-lectively what we could not achieve individually.

Another element of our project’s success is our deliberateattention to group process (Lyons 2011, forthcoming). Wehave made effective communication a priority for our projectteam, and have created space for dialogue about all aspects ofthe project— our goals, how they are prioritized, and how wewill achieve them. We discuss these issues on an ongoingbasis as the project evolves. Part of our commitment toprocess involved setting the terms for our project team inter-actions, in the form of a project charter which specified indi-vidual and collective roles and responsibilities, and how wewould resolve differences of opinion. The different perspec-tives of respective team members has led to a cross-fertiliza-tion of ideas and also raised important intellectual propertyquestions related to access, control, and representation ofInuvialuit culture and ideas.

What have been the major challenges of the project?

Our major challenges have revolved around time andexpense, and issues of control and meaningful communityengagement. Northern projects are exceptionally expensivedue to northern cost of living, large distances between com-munities, and air travel. While our project has represented along-term, well-funded, and wide-ranging effort, we havestill had to work hard to keep our goals reasonable and tostay focused on them. We have coordinated interviews, dis-cussions, meetings, and workshops with Inuvialuit Elders,youth, and other community members and their organiza-tions from many towns and hamlets. Elders are frequentlybusy with their families and their work on the land. Accom-modating their schedules has been a significant priority forthe team.

A particular challenge of producing a virtual exhibit is theamount of time required to manage and present the data col-lected. We have worked with both Inuvialuktun and Englishspeakers, and have a great deal of raw data to transcribe,translate, and convert into a format suitable for the Inu-vialuit Living History website. We have sought to reflect

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 1. Communities of the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Canadian Western Arctic.

45September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

community goals and interests through the website, requir-ing extensive community consultation. This focus on localknowledge has required us to negotiate interpretive controlwith the Smithsonian establishment. We have also had tonegotiate the requirements and constraints of major heritageinstitutions and funders.

Once launched, obtaining meaningful community feedbackand input on the site’s content has been an ongoing chal-lenge, largely because teachers are busy, settlements arewidespread, access to the internet is not universal, and notall of us live in the north to help with this work. We lookahead to the challenges of long-term hosting and preserva-tion of digital information, and to ensuring that this valuableinformation will be accessible for generations to come.These factors have required us to be both creative and proac-tive in our consultation efforts, which are ongoing.

How has the project been received in the Inuvialuitand anthropological communities?

The Inuvialuit community has embraced this project withenthusiasm. Many Inuvialuit Elders once knew or used spe-cific types of objects in the collection, and they are very inter-ested in passing knowledge about these items, and thelifestyle they represent, to their grandchildren and greatgrandchildren. Inuvialuit hunters, seamstresses, and materi-al culture specialists are actively studying objects in the col-lection and experimenting with making and using them.Seamstress Freda Raddi traced clothing patterns during ourvisit to the Smithsonian and sewed traditional boots for hergrandchildren. One of our project team Elders, James Poki-ak, carved a pair of snow goggles like those he’d seen inWashington for his daughter. Other project team membershave had the opportunity to share our experiences with theMacFarlane Collection through lecture tours. After one com-

munity presentation, a young woman called Mervin Joe ahero for making the collection accessible to Inuvialuit peo-ple. Other cultural communities have been inspired by ourwork and talked about pursuing the same kind of relation-ships with their ancestral collections. The tremendous inter-est in the website within the Inuvialuit community engen-dered considerable impatience for its completion. This isone of very few online projects representing Inuvialuit cul-ture, and the community is anxious to use and circulateresources such as the virtual exhibit, lesson plans, and inter-active place name maps.

Our project has also sparked interest in the archaeologicaland anthropological communities. The project has beenwidely presented and discussed in archaeological venues andmeetings. Our relationship to the IPinCH Project, an inter-national network of cultural heritage scholars and local prac-titioners, has provided a forum for critical discussions ofcommunity-based practice and intellectual property issues,as have other opportunities to present the project, such asthe workshop “After the Return: Digital Repatriation and theCirculation of Indigenous Knowledge” at the Smithsonian’sNational Museum of Natural History in January 2012 (Chris-ten et al. 2012). The launch of the Inuvialuit Living Historywebsite has led to many requests for information from schol-ars and communities worldwide about our work, methods,and deliverables.

Conclusion

Contemporary archaeology and ethnology are increasinglycharacterized by new approaches to the study of material cul-ture, and by cooperative working relationships across cultur-al and disciplinary borders (Lyons forthcoming). Through theInuvialuit Living History Project, we have sought to engagewith a collection of ancestral objects and to share this knowl-edge in its source community. We have been very encouragedby the excitement with which Inuvialuit are re-creating andusing these objects in a modern context. Community interestis also spurring us towards archaeological investigations atthe Fort Anderson trade post, and mapping Inuvialuit knowl-edge and stories about the Anderson River landscape.

For our research team, the Inuvialuit Living History projecthas represented a collaborative process, and a final productthat we are proud of; however, we also see the website as abeginning, more than an end in itself. The digital platformthat we have developed to show the MacFarlane Collection andits significance in Inuvialuit communities is designed forongoing contributions and contextualization with local knowl-edge and media documentation. Our challenge will be to sus-tain the momentum of the project into the future and for ourgroup to persist in the self-conscious negotiation of group pri-orities, responsibilities, and ethical research practices.

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 2. Elder Albert Elias sporting a pair of snow goggles from theMacFarlane Collection (Kate Hennessy photo).

46 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

References CitedChristen, Kim, Joshua Bell, and Mark Turn

2012 Digital Return. Electronic document, http://digitalre-turn.wsu.edu, Accessed April 1, 2012.

Kate Hennessy, Ryan Wallace, Nicholas Jakobsen, and CharlesArnold

2012 Virtual Repatriation and the Application ProgrammingInterface: From the Smithsonian Institution’s MacFarlaneCollection to “Inuvialuit Living History”. Proceedings ofMuseums and the Web 2012, San Diego, edited by N. Proc-tor and R. Cherry. Archives and Museum Informatics, SanDiego.

Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre2012 Inuvialuit Pitqusiit Inuuniarutait: Inuvialuit Living History.

Electronic document, http://www.inuvialuitlivinghistory.ca,accessed April 1, 2012.

Loring, Stephen, Natasha Lyons, and Maia LePage 2010 Inuvialuit Encounter: Confronting the past for the future.

An IPinCH Case Study. Arctic Studies Center Newsletter No.17: 30–32.

Lyons, Natasha Forthcoming Where the Wind Blows Us: The Practice of Criti-

cal Community Archaeology in the Canadian North. TheArchaeology of Colonialism in Native North AmericaSeries, University of Arizona Press, Tucson, in press.

Lyons, Natasha, Kate Hennessy, Charles Arnold and Mervin Joe,with contributions by Albert Elias, Stephen Loring,Catherine Cockney, Maia Lepage, James Pokiak, BillyJacobson, and Darrel Nasogaluak

2011 The Inuvialuit Smithsonian Project: Winter 2009–Spring2011. Unpublished report on file with Department ofCanadian Heritage, Ottawa. Online at:www.irc.inuvialuit.com

Morrison, David2006 Painted Wooden Plaques from the MacFarlane Collection:

The Earliest Inuvialuit Graphic Art. Arctic 59(4):351–360.

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Figure 3. Search page from the Inuvialuit Living History website.

47September 2012 • The SAA Archaeological Record

This paper ruminates on the collaborative partnershipthat we have developed with the Barunga, Wugularr,Manyallaluk and Werenbun communities in the

Northern Territory, Australia, over the last two decades. Weuse “Barunga” as a shortened term to refer to all of thesecommunities, as we are usually based at Barunga. We havestructured the paper around points of change to give a cumu-lative sense of how our collaborations have developed overtime.

The communities that we work in are located in a remotearea of northern Australia (Figure 1). The populations ofthese communities are overwhelmingly Aboriginal, andrange from 35 people at Werenbun (Rachael Willika person-al communication 2012) to 511 at Wugularr (AustralianBureau of Statistics 2012). The only non-Aboriginal peopleliving in these communities are teachers, nurses and admin-istrators, met almost invariably in formal situations. Thefirst language in the region is Kriol, a creole that emergedduring the contact period of the early to mid twentieth cen-tury (Smith 2004). Many community people are not fluent inEnglish and are shy or reticent in their interactions with non-Aboriginal people. The economic status of communities isvery low, with under-employment or unemployment ofaround 50 percent and subsequently low incomes (Aus-tralian Bureau of Statistics 2012), low levels of car owner-ship, infant mortality rates that are 1.8 to 3.8 times as highas those for non-Indigenous children and life expectanciesthat are 10–12 years shorter than those of non-IndigenousAustralians (Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2012;Council of Australian Governments 2011).

Starting Point: First Evening

We went to Barunga in 1990 to conduct Smith’s (1996) doc-toral research on the social and material variables of an Abo-riginal artistic system. The first evening we agreed to drive agroup of eight people forty kilometers to the neighboring

community of Beswick. We agreed to do this partly becausewe wanted interaction with local people, and partly becausewe feared that no one would want to talk to us, that we wouldnot be able to collect rich ethnographic data. The decision todrive people to Beswick was a mistake. It was the equivalentof putting a flashing neon light over our caravan, with thesign “taxi” or “free taxi,” and for many months we were given“humbug” at all hours of the day and night by people whowanted us to drive them somewhere, sometimes hundredsof kilometers away.

This dilemma did not dissipate until we were accepted intothe extended family of senior lawman, Peter Manabaru andhis wife, Lily Willika. Then, at Peter’s suggestion we sentpeople to get permission from him, since he was “boss” forour car. We found ourselves under the auspices of a seniorlawman, and the problem was resolved.

Point of Change: From Researchers and ‘Informants’ to Family

We started with a clear focus on Smith’s doctoral research onAboriginal art (Smith 1996). Though he is an anthropologistnow, Jackson started his academic foray as an English majoraccompanying Smith on her field trips, where he thought hecould just stay in the background. Wrong! Smith would askthe old men questions and they would sit facing Jackson andgive him the answers as though Smith wasn’t present. So welearned that there was no right to knowledge and that thetransition of knowledge was determined by gender. More-over, it seemed that our Aboriginal teachers saw Jackson’scasual or reluctant attitude to research as an attribute and sohe was taught much without having to question people. Thebest teaching occurred when people were in the bush, whichacted as a mnemonic that made questions unnecessary.

Gary Jackson’s main teacher was Peter Manabaru. Over theyears these two became best friends. Manabaru lived with

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

SHARED LIVESA COLLABORATIVE PARTNERSHIP IN ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIA

Claire Smith and Gary Jackson

Claire Smith and Gary Jackson are affiliated with the Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide. S.A. 5001.

Australia, and may be reached at [email protected] and [email protected] respectively.

48 The SAA Archaeological Record • September 2012

Smith and Jackson whenever they were in the communityand he stayed in their home away from the community forclose to a year at a time. One difficulty of this situation is thatyou end up with middle class researchers talking with upperclass Aboriginal teachers, so there is a class bias in the data.Also, the responsibilities of family means a lot of extra effort,as with any family: “Could you drive me to visit family in hos-pital tonight?” where the hospital is a 160 kms round trip.Or, “We have to take sticks and bash up that other familytomorrow because they went to the police about yournephew injuring one of their family.” These costs and bene-fits come together as part of the package of collaboration.

Peter recently walked away. That is, he was called to joinfamiliar spirits in the countryside and disappeared. No foot-prints are ever found as these “clever men” walk above theground and the local police called Jackson to fly up to help inthe search. Jackson spent two weeks searching the local bushin vain. Initially, he was very keen to find Manabaru but aftera while he wondered what he would do if he did discover himin a cave. Manabaru was doing what was right and had toldfamily members of a spirit wife, son, and daughter who livedin a cave and were presumably helping him on this adven-ture. Jackson is now pleased he did not have to decide whatto do. Manabaru has never been found.

Point of Change: Jimmy Becomes Lamjerroc

When conducting Smith’s doctoral research we workedclosely with the senior traditional owner, Phyllis Wiynjorroc.Towards the end of a year of living in the community, afterone interview she pointed to our 18-month-old son and said“What’s his name?” We gave his name, Jim, but she said“No, his Aboriginal name.” We gave his “skin” name, as part

of the kinship system, Gela. She said “No, his Aboriginalname” ... and when we continued to look blank she said “Hisname is Lamjerroc, the same as my father.”