The Uniform Commerical Code as Federal Law: United States ...

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

Transcript of SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-1

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE

ARTICLES 3 AND 4

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-2

The Uniform Commercial Code

None would argue that the United States of America is a world leader when it comes to commerce. A great many factors contribute to our status as a commercial giant, but perhaps no single factor has had as large an impact on commerce in this country as the Uniform Commercial Code, more commonly referred to as the “UCC,” or simply the “Code.”

But what exactly is the UCC? It is the body of “law” which provides the rights, duties, responsibilities, and liabilities of parties to virtually every kind of commer-cial transaction. The word “law” appears in quotation marks because the UCC is not a true law in and of itself. The UCC operates more as a guideline from which each of the state legislatures has enact-ed its own laws governing commerce within its borders.

The UCC has been in formal existence since 1952. It is the product of the joint efforts of the American Legal Institute (ALI) and the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL). Since its original enactment, the UCC has undergone — and will con-tinue to undergo — many changes and revisions. Each time an article of the UCC is revised, it is up to each state to amend its own laws if it chooses to do so.

The Code is at present divided into 11 sections:

Article 1: General Provisions

Article 2: Sales

Article 2A: Leases

Article 3: Negotiable Instruments

Article 4: Bank Deposits and Collections

Article 4A: Funds Transfers

Article 5: Letters of Credit

Article 6: Bulk Transfers

Article 7: Warehouse Receipts, Bills of Lading, and Other Documents of Title

Article 8: Investment Securities

Article 9: Secured Transactions

In this section we will discuss some of the provisions included in Article 3, Negotiable Instruments and Article 4, Bank Deposits and Collections. We will attempt to cover the provisions that are most likely to have a regular impact on credit union operations. As such, this is not intended to provide an exhaus-tive review of all of Articles 3 and 4. It is intended as a tool to be used in your daily operations, to assist you in under-standing the credit union’s rights as pro-vided in the Code.

Again, the UCC is not, of itself, the law of the land. Each state and the District of Columbia have passed their own versions of the Code. Happily, most of the provisions in the various state UCCs are, indeed, identical to those we will discuss. But this guide should not be relied upon to ascertain your legal status with respect to a specific com-

Section 5 – Uniform Commerical Code Articles 3 and 4

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-3

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

mercial transaction. When problems present themselves in the area of com-mercial law, you should look to your specific state’s statute — and your credit union’s attorney — to determine your rights, duties, and responsibili-ties. That having been said, the specific references to the Code throughout this chapter and the next refer not to any particular state’s code (unless otherwise indicated), but rather to the Uniform Commercial Code as adopted by the ALI and the NCCUSL.

General Background of UCC Articles 3 and 4

The body of law that has evolved into present-day UCC Articles 3 and 4 actu-ally had its origin in the Middle Ages. Merchants, traders, and the like learned that it was indeed a dangerous world. One could simply not afford to risk trav-eling the seven seas in search of com-mercial transactions while carrying one’s gold. To solve this dilemma, these mer-chants devised a system of paying for goods with paper rather than coin.

Merchants discovered that they could sell their goods and, rather than accept-ing gold — or any other type of tangible payment — they could direct their buyer to use a written instrument pledging a payment to a third party, or “payee.” The merchant could then, as the sys-tem developed, use that instrument to satisfy some debt he owed another by transferring the ownership of the instru-ment to his creditor. That creditor could do the same until eventually the instru-ment found its way to and was paid by the original buyer. In essence, a single

instrument could be used to conduct a series of transactions without the need for cash.

Over time this written instrument came to be known as a draft. A typical draft involves three parties: “drawer,” “drawee,” and “payee.” The merchant was the drawer — he used the instru-ment to draw upon the debt owed by the buyer. The buyer, then, became the drawee. And the merchant’s creditor became the “payee” of the draft. The act of the payee signing over the draft to another creditor in the chain came to be known as “endorsement,” and the trans-action between two parties in the chain was referred to as “negotiation.”

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, a similar type of instrument was widely in use — the “note.” A note is simply a promise by one party (the “maker”) to pay another person (the “payee”). It wasn’t long before notes became negotiable in much the same fashion as drafts. Throughout the course of the 18th and 19th centuries English and American judges developed the common law relating to negotiable instruments. The courts understood that a cornerstone of the success of the commercial system was the protection of the good-faith purchasers of notes and drafts. As we will address below in our discussion of Holders in Due Course, generally speaking, a good-faith purchaser of a negotiable instrument is protected from nearly all claims and defenses which might otherwise be used to prevent him from receiving payment.

Here in the U.S., Congress began its efforts at regulating the payment system during the 19th century. During the first half of the century, state banks issued

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-4

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

notes that were used like money in com-merce. Human nature being what it is, there were more than occasional abuses. Some banks began issuing notes that were really not backed by sufficient cash — others made their notes redeem-able only at remote branches, secure in the knowledge that nearly no one would jump through the necessary hoops to obtain his payment. In an attempt to bring about order in what was develop-ing into a rather chaotic scene following the Civil War, Congress imposed a tax on state bank notes in order to encour-age more widespread use of the “green-backs” then issued by national banks.

This might have been disastrous for the state banks had they not managed to introduce Americans to checking accounts as a means to make pay-ments. Of course, Americans have been using checking accounts ever since, in increasingly greater volume.

A “check” is simply a draft that is drawn on a bank, thus the common law which had developed around negotiable instruments applied to most aspects of personal check transactions. The pro-cess of collecting checks evolved into a series of private agreements between banks.

As things progressed, subtle differ-ences evolved in the case law of indi-vidual states with respect to negotiable instruments law and bank collection law. By the end of the 19th century, it was clear that some uniformity had to be brought into the system so parties to interstate transactions could be rea-sonably certain of their rights, duties, and responsibilities. In 1896, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws sponsored the

Negotiable Instruments Law (NIL) — the predecessor to today’s UCC Article 3 — and it was eventually adopted by every state. But the NIL did not regulate check collections.

In 1913 the Federal Reserve was established. One of its purposes was to standardize the check collection sys-tem in order to improve its efficiency. Ultimately the Federal Reserve played a great role in simplifying the routing of checks by providing a more efficient clearinghouse to compete with the pri-vate banking system. But what about those banks which chose not to belong to the Federal Reserve System? Many efforts to develop a model code govern-ing check collections outside the federal system were attempted with varying lev-els of success. The most successful, the Bank Collection Code (BCC) of 1928, was adopted by only 18 states.

In 1940, the NCCUSL resolved to replace all of its various uniform acts (including the NIL) with a centralized, comprehensive commercial code. The American Legal Institute joined in the effort, and the UCC was born. Article 3, then entitled “Commercial Paper,” and Article 4, “Bank Deposits and Collections,” formed the cornerstone of the laws governing negotiable instru-ments and check collections. As men-tioned, Articles 3 and 4 were eventually adopted by every American jurisdiction.

Throughout the last half of the 20th century commerce has evolved — at times outgrowing various provisions throughout the UCC. As such, many of its articles have undergone revision through the years, including Articles 3 and 4. Others have been added — most significantly for our purposes, Article

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-5

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

4A in 1989, which is devoted to elec-tronic funds transfers (we will discuss Article 4A in more detail in the next sec-tion of this module). The most recent of those revisions was made in 1990, at which time Article 3 was rewritten (and given its present name, Negotiable Instruments) and Article 4 was substan-tially revised.

Article 3 of the Code is broken into six parts. Part 1 addresses general provi-sions and definitions; Part 2 deals with the concepts of negotiation, transfer, and endorsement; Part 3 is devoted to the enforcement of negotiable instru-ments; Part 4 speaks to the liability of parties to transactions involving nego-tiable instruments; Part 5 deals with the dishonor of negotiable instruments; and Part 6 addresses discharge and pay-ment (and is beyond the scope of this manual).

Article 4 contains five parts: Part 1 addresses general provisions and defini-tions; Part 2 discusses the collection of items with respect to depositary and collecting banks; Part 3 deals with col-lection of items with respect to payor banks; Part 4 addresses the relationship between payor banks and their custom-ers; and Part 5 discusses the collection of documentary drafts (which is beyond the scope of this module).

In the pages that follow, we will review details of these various parts. Again, the intent of this module is not to provide the reader with the definitive source of information regarding these two articles. Our goal is to highlight some of the more prominent aspects of various parts of these articles in terms of our daily lives managing the affairs of

credit unions.Note: Each section of the UCC,

as adopted by the NCCUSL and the ALI, was accompanied by an “Official Comment.” While these comments have not been enacted by state legislatures, judges and lawyers frequently rely on them as they attempt to resolve mat-ters under the various Code provisions. We will occasionally refer to the Official Comments (or simply “comments”) throughout this section and the next.

UCC Article 3: Negotiable InstrumentsPart 1— General provisionsScope

Article 3 applies to “negotiable instruments,” defined in §3-104 as signed writings that order or promise the payment of money (a more detailed defi-nition of “negotiable instruments” can be found below). This article does not apply to “payment orders,” which are governed by Article 4A, nor does it apply to securities transactions. Securities transactions are governed by Article 8 of the U.C.C. and are beyond the scope of this manual. The comment to §3-102 acknowledges that occasionally a par-ticular writing may fit the definition of both a “negotiable instrument” under Article 3 and an “investment security” under Article 8. In those cases, Article 8 is controlling.

A number of terms used throughout the UCC are given very specific mean-ings within the Code. Article 3 is no exception to that general premise.

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-6

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

§3-103 sets forth several definitions which we will briefly discuss throughout the context of this chapter. Whenever attempting to wind your way through Article 3, it is quite useful to bear in mind that most of the terms in the arti-cle have these specific meanings.

Negotiable instruments

As we’ve discussed, a negotiable instrument is a signed writing that orders or promises the payment of money. More specifically, §3-104 defines the term “negotiable instru-ment” as “an unconditional promise or

order to pay a fixed amount of money, with or without interest or other charges described in the promise or order, if all of the following apply:

• It is payable to bearer or to order at the time it is issued or first comes into possession of a holder.

• It is payable on demand or at a definite time.

• It does not state any other undertaking or instruction by the person promising or ordering payment to do any act in addition to the payment of money.

Refer to figure 5.1 for an illustration

Figure 5.1 The Personal Check

Figure 5.1 illustrates the UCC requirements for turning an ordinary piece of paper into a negotiable

instrument — in this case, the most common kind of negotiable instrument handled by credit unions: the

personal check. In order to create a negotiable instrument, it must be an order to pay; it must state who

is to be paid (the “payee”); it must state a sum certain; it must identify who is ordered to pay (the “payor

bank”); it must become payable on or after a specified date; it must identify the party making the order

(the “drawer”); and it must be signed by the drawer.

5-8 MODULE 1 DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS © DECEMBER 1999 CUNA & AFFILIATES

Figure 5.1 The Personal Check

Figure 5.1 illustrates the UCC requirements for turning an ordinary piece of paper into anegotiable instrument — in this case, the most common kind of negotiable instrumenthandled by credit unions: the personal check. In order to create a negotiable instrument, itmust be an order to pay; it must state who is to be paid (the “payee”); it must state a sumcertain; it must identify who is ordered to pay (the “payor bank”); it must become payableon or after a specified date; it must identify the party making the order (the “drawer”); andit must be signed by the drawer.

Negotiable instruments — also referred to in the Code simply as “instruments”— are divided into two primary categories: drafts and notes. A draft is aninstrument that is an order to pay (for example, a check or share draft drawn on acredit union), while a note is an instrument that is a promise to pay (such as atypical installment loan). Because the primary emphasis in this manual is the lawwith respect to the deposit side of credit union operations, our review of Article 3will focus on its application to drafts as opposed to notes.

The comment to revised Article 3 makes clear that a credit union share draftfalls within the meaning of the word “check” — thus credit union share drafts maybe referred to as “checks” for purposes of the UCC. In fact, Article 3 includes creditunions within the definition of the term “bank.” Although there are importantdistinctions between credit unions and banks, it is quite useful to treat them assynonymous terms under the Code, to help ensure a uniform operation of thenation’s checking account system.

To whom is an instrument payable?The payee of an instrument is the person to whom an instrument is payable.

Typically, a cursory review of a check will reveal the party to whom it is payable.

Level Two

John Doe

Jane A. Doe1234 1st StreetThe City, MI 98765

Pay to the Order of(Order to Pay)

Credit Union (Payor Bank)AddressCity, State Zip Code

Memo

(Payee's Name)

(Sum Certain Alpha)

(Drawer's Signature)

Dollars

$

Date1252

Sum Certain Numeric

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-7

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

of the most common type of negotiable instrument, the personal check.

Negotiable instruments — also referred to in the Code simply as “instru-ments” — are divided into two primary categories: drafts and notes. A draft is an instrument that is an order to pay (for example, a check or share draft drawn on a credit union), while a note is an instrument that is a promise to pay (such as a typical installment loan). Because the primary emphasis in this manual is the law with respect to the deposit side of credit union operations, our review of Article 3 will focus on its application to drafts as opposed to notes.

The comment to revised Article 3 makes clear that a credit union share draft falls within the meaning of the word “check” — thus credit union share drafts may be referred to as “checks” for purposes of the UCC. In fact, Article 3 includes credit unions within the defini-tion of the term “bank.” Although there are important distinctions between cred-it unions and banks, it is quite useful to treat them as synonymous terms under the Code, to help ensure a uniform oper-ation of the nation’s checking account system.

To whom is an instrument payable?

The payee of an instrument is the per-son to whom an instrument is payable. Typically, a cursory review of a check will reveal the party to whom it is pay-able. But occasionally that is not readily apparent. §3-110 addresses a number of different scenarios to assist the credit union in determining who is entitled to the payment of an instrument.

First and foremost, this section makes clear that the person to whom an instru-

ment is initially payable is determined by the intent of the person signing as the issuer of the instrument (for example, the “drawer”). In the rare instance that more than one person signs as a drawer, and not all of the signers intend the same person as payee, the instrument is payable to any person intended by one or more of the signers.

Occasionally, the individual to whom an instrument is payable will not be identified by name. This is not nec-essarily fatal to the issue of whether the instrument is negotiable. §3-110 provides that the payee can be identi-fied “in any way, including by name, identifying number, office, or account number.” §3-110(c). If the instrument is payable to an account identified by number and to a named person, the named person is entitled to payment even if he is not the owner of the identi-fied account. §3-110(c)(1).

Section 3-110 addresses other fairly rare situations as well. It makes clear that if an instrument is payable to a trust, an estate, or a person described as the trustee or representative of a trust or estate, the instrument is payable to either the trustee, the representative, or a successor of either, regardless whether a beneficiary or estate is also named in the instrument. §3-110(c)(2)(i). Further, it provides that if an instrument is pay-able to a person described as the agent or representative of another named person, the instrument is payable to the agent/representative, his successor, or directly to the represented person. (§3-110(c)(2)(ii))

The same section provides that if an instrument is payable to a person described as holding an office, the

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-8

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

instrument is payable to the named per-son, the incumbent of the office, or a successor to the incumbent. (§3-110(c)(2)(iii))

Multiple payees

The 1990 revision to Article 3 clari-fied an ambiguity in the law with respect to multiple payees. A check payable to “John Doe or Jane Doe” can be paid to either John or Jane Doe. If a check is payable to “John Doe and Jane Doe,” neither John nor Jane Doe can receive payment without the signature of the other. Those provisions are not new. But Revised Article 3 addressed for the first time the situation where the words “and” or “or” do not appear. If, for example, a check is payable to “John Doe, Jane Doe,” Revised Article 3 pro-vides that it is payable to either John or Jane Doe. §3-110(d).

At least one court has even held that the use of a forward slash between names on a check made that check payable to either party. In that case, three checks payable to “San Fran Plumbing, Inc./Danco, Inc.” were cashed by a bank even though the endorsements of Danco, Inc., (unbe-knownst to the bank, of course) were forged. A New Jersey court held that the checks were properly payable to either party in the alternative — since San Fran Plumbing, Inc., did, in fact, negoti-ate them, that negotiation was proper. In the words of the court: “The short, slanting stroke is called a ‘virgule,’ and in modern usage is equivalent to the word ‘or.’ Further, an ambiguous co-payee designation should be considered to be in the alternative.” Danco Inc. v. Commerce Bank/Shore, N.A., 29 UCC

Rep Serv 2d 513, 290 NJ Super 211, 675 A2d 663.

Essentially, the Code has placed the burden of clearly expressing the inten-tion that a check be negotiated by all of the named payees on the person issuing the instrument. As a practical matter, many credit unions routinely require that all named parties in such cases endorse the instrument. Although this is not a requirement under the Code, such a poli-cy could help the credit union avoid find-ing itself in the middle of a feud between John and Jane Doe at a later time.

Conflicting amounts — which one controls?

A typical check presented at the credit union for deposit will include the words “Pay to the order of...” along with an individual’s or organization’s name or account number, followed by a numeric expression of the amount of payment. The check will also then spell out the amount of the payment using words (for example, “Ten Thousand Dollars and No Cents”). Suppose a check contains an inconsistency between the numeric amount and the spelled-out amount? Section 3-114 provides that in such a case words prevail over numbers. Thus a check payable to the order of John Doe orders the payment of “$1,000” (numeric) and “Ten Thousand Dollars” (spelled-out), it is properly payable in the amount of ten thousand dollars.

Statute of limitations

Prior to Revised Article 3, the issue of when the statute of limitations expired in an action to enforce an instrument was less than clear. Under the 1990

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-9

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

revision, a party entitled to payment of a personal check must now bring a law-suit to enforce the payment within three years after the check has been dishon-ored or 10 years from the date the check was issued, whichever occurs earlier.

Part 2 — Negotiation, transfer, and endorsementNegotiation

“Negotiation” of an instrument means a transfer of possession of the instrument, by a person other than the issuer, to another person. The person to whom this transfer is made is known as the “holder” of the instrument. Except for a transfer made by a remitter of a cashier’s check or teller’s check — for example, the person who purchases one of those instruments but makes it pay-able to another party — if an instrument is payable to an identified person, it can-not be negotiated without the transfer of possession and the endorsement by the holder. An instrument that is payable to bearer (for example, an instrument that does not name a payee, but is rather payable to anyone who has possession of it) can be negotiated simply by transfer of possession. §3-201.

Transfer

Unless two parties have otherwise agreed, if an instrument is transferred from one party to another for value, but the transferor neglects to endorse the instru-ment, the person to whom the instrument was transferred has the right to force the transferor to supply his endorsement. §3-203. However, in such a case, negotia-tion does not take place unless and until the endorsement is made.

Endorsement

“Endorsement” generally means a signature (other than the signature of the maker, drawer, or acceptor) on an instrument for the purpose of negoti-ating it or restricting payment of the instrument. The Code provides for differ-ent types of endorsements. An endorse-ment is a “special endorsement” if it includes the signature of a holder and identifies a person to whom the instru-ment will then be made payable. For example, if a check is payable to John Doe, and he endorses it “Pay to the order of Jane Doe” and signs his name, John Doe has made a “special endorse-ment.” The check is then payable only to Jane Doe (who, in turn, can add her own special endorsement). §3-205(a).

If the holder simply signs his name with no other instructions or wording, the endorsement is known as a “blank endorsement.” A check endorsed in blank becomes payable to anyone who later comes into its possession unless and until someone adds a special endorsement. §3-205(b).

An endorsement which purports to limit payment of an instrument to a particular person is generally not effec-tive in stopping further transfers. For example, if a check is endorsed “Pay Jane Doe Only,” Jane Doe may negoti-ate the check to subsequent holders who may then disregard the restriction. §3-206(a).

Another type of restrictive endorse-ment, which is a frequent cause for concern, involves a payee endorsing a check “Pay to the order of Jane Doe, in trust for Jim Doe.” Suppose in a case like this that Jane then endorses the check in blank, and delivers it to another

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-10

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

individual, a depositary bank, or the bank on which it was drawn, for pay-ment. The Code makes clear that, unless any of these parties has notice that Jane has breached any fiduciary duty owed to Jim, they can safely pay Jane. If any party has notice that Jane is using the funds for her own personal benefit, that party could be liable to Jim if they pay the check to Jane. §3-206(d).

Part 3 — Enforcement of instrumentsThe “Holder in Due Course” doctrine

Generally speaking, any holder of an instrument is entitled to its enforce-ment. There are, however, several defenses to the payment of an instrument which can be raised by the obligor (the person obligated to make the payment). Consider, for example, the case of the sale of goods between two parties — call them Smith and Jones — where Smith has agreed to purchase goods from Jones and Jones has agreed to accept payment by personal check. In this example, with respect to the personal check, Smith is the obligor and Jones is the obligee. Let’s suppose further that Jones never delivers the goods. His failure to deliver the goods provides a defense to Smith, and he can stop payment on the check without incurring liability to Jones (stop-payment orders are addressed below in our discussion of Article 4).

But what if, prior to Smith’s realiza-tion that the goods would not be deliv-ered, Jones negotiated the check to Wilson? Will Smith be entitled to raise the same defense against Wilson as he could against Jones? The short answer is: It depends.

Whether Smith can raise a defense to payment of the personal check against Wilson depends on both (a) the type of defense he seeks to raise; and (b) whether or not Wilson is a “Holder in Due Course.”

A “Holder in Due Course” (we’ll refer to it as an HIDC) has special rights to enforce an instrument. To put it another way, HIDC-status limits the types of defenses to payment that can be raised. A holder of an instrument becomes an HIDC if and only if 1) at the time the instrument is issued or negotiated to the holder it does not bear “such apparent evidence of forgery or alteration or is not otherwise so irregular or incomplete as to call into question its authenticity” (§3-302(a)(1)); and 2) the holder took the instrument:

• For value.

• In good faith.

• Without notice that the instrument was overdue or had been dishonored or there was an incurred default with respect to payment of another instru-ment issued as part of the same series.

• Without notice that the instrument contained an unauthorized signature or had been altered.

• Without notice of any claim to a prop-erty right or possessory right in the instrument §3-302(b).

At the risk of oversimplification, think of a Holder in Due Course as an inno-cent, impartial bystander to the primary obligation between two parties — a good-faith purchaser with special powers.

The types of defenses that can be raised by an obligor are divided into two

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-11

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

important categories: “real defenses,” and all others (sometimes referred to as “personal defenses”). An obligor has a “real defense” to the payment of an instrument based on any of the following:

• Infancy of the obligor, to the extent the age of the obligor is a defense to a simple contract (in most states, a minor can void a contract until he reaches the age of majority — typically age 18).

• Duress, lack of legal capacity, or ille-gality of the transaction which under other law nullifies the obligation of the obligor (for example, if a contract was signed at gun point, it would probably be considered to have been signed under duress; if the obligor was men-tally incompetent, his contract is void; or if a person’s debt arises from an illegal gambling transaction, it is not enforceable).

• Fraud that induced the obligor to sign the instrument without knowing what the instrument was.

• Discharge of the obligor in insolvency proceedings (typically bankruptcy).

These “real defenses” are set forth in §3-305(a)(1). Several other defenses to payment — the so-called “personal defenses” — can typically be raised by obligors, including:

• Nonissuance of the instrument, con-ditional issuance, and issuance for a special purpose.

• Failure to countersign a traveler’s check.

• Modification of the obligation by a separate agreement.

• Payment that violates a restrictive endorsement.

• Instruments issued without consider-ation or for which promised performance has not been given.

• Breach of warranty when a draft is accepted.

• Misrepresentation.

• Mistake in the issuance of the instrument.

This distinction between “real defens-es” and all others is important because “real defenses” are effective against all holders — even HIDCs. However “per-sonal” defenses are not effective against an HIDC. §3-305(c). The essence of the HIDC doctrine is essentially that an hon-est third party who takes a negotiable instrument for value generally should not be made to suffer the same defenses as the party who negotiated the instrument to him. The doctrine separates the obli-gation to pay money from the underlying transaction which gave rise to that obli-gation. If two parties, A and B, have a falling out, the law regards it as unfair to drag third party C into the middle of it.

Returning to our example, if Wilson took the check from Jones: for value; in good faith; without notice that the instrument was overdue or had been dishonored or that there was an incurred default with respect to payment of another instrument issued as part of the same series; without notice that the instrument contained an unauthor-ized signature or had been altered; and without notice of any claim to a property right or possessory right in the instru-ment, then — assuming the check

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-12

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

wasn’t an obvious forgery — Wilson is an HIDC, and Smith’s defense to payment is ineffective against Wilson because it does not fit within the category of “real” defenses. Smith, of course, still can recover against Jones for Jones’ breach of contract.

Enforcement of lost, destroyed, or stolen instruments

Occasionally an instrument will be lost, destroyed, or stolen. In such a case, is the individual who was entitled to pay-ment on the instrument simply out of luck? Perhaps not. Section 3-309 pro-vides that the payee (or other holder, as the case may be) is entitled to enforce a lost, destroyed, or stolen instrument if:

• He was in possession of the instrument and entitled to enforce it immediately before it was lost, destroyed, or stolen.

• The loss of possession was not the result of a transfer by the individual or a lawful seizure.

• The person cannot reasonably obtain possession of the instrument because it was destroyed, its whereabouts cannot be determined, or it is in the wrongful possession of an unknown person or a person that cannot be found.

It should be noted — and should come as no surprise — that an indi-vidual attempting to enforce a lost, destroyed, or stolen instrument will have to jump through some substantial hoops in order to obtain payment. He must file a lawsuit in order to enforce the instrument. In that lawsuit, he must prove both the terms of the instrument and his right to enforce the instrument.

The Comment to §3-309 provides that a judgment to enforce the instrument can-not be given unless the court finds that the defendant (for example, the issuer) will be “adequately protected” against a claim to the instrument by a holder who might show up at a later date. The court is given discretion in determining how adequate protection is to be assured. It can — and usually does — take the form of an expensive bond for the amount of the check. Some courts have made those “hoops” even more difficult by raising the burden of proof. Typically in civil litigation, the burden of proof on a plaintiff is by a preponderance of the evidence — for example, the facts show that it is more likely than not that a given allegation is true. But at least one court — in Minnesota — required that a claimant under §3-309 prove its case by “clear and convincing evidence” — a standard that is higher than the prepon-derance-of-the-evidence standard. See NAB Asset Venture II, L.P. v. Lenertz, Inc., 36 UCC Rep Serv 29474 (Minn App 1988).

Lost, destroyed, or stolen cashier’s check, teller’s check or certified check

The Code provides a special proce-dure in the case of lost or destroyed cashier’s checks, teller’s checks, or certified checks, set forth in §3-312. All three are defined in Article 3 as follows:

• A “cashier’s check” is a draft with respect to which the drawer and draw-ee are the same bank or branches of the same bank. §3-104(g).

• A “teller’s check” is a draft drawn by a bank on another bank or payable at or through a bank. §3-104(h).

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-13

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

Figure 5.2 Cashier’s and Teller’s Checks

Cashier’s Check

Teller’s Check

Figure 5.2 shows examples of a cashier’s check and a teller’s check. These negotiable instruments are

similar in most respects. A cashier’s check is a check that a bank draws on itself. A teller’s check is a

check that a bank draws on another bank. Note the “payable through” notation on the teller’s check.

Keep in mind, for purposes of the UCC, credit unions are “banks.”

Figure 5.2 Cashier’s and Teller’s Checks

The Cashier’s Check

The Teller’s Check

Figure 5.2 shows examples of a cashier’s check and a teller’s check. These negotiableinstruments are similar in most respects. A cashier’s check is a check that a bank draws onitself. A teller’s check is a check that a bank draws on another bank. Note the “payablethrough” notation on the teller’s check. Keep in mind, for purposes of the UCC, creditunions are “banks.”

5-16 MODULE 1 DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS © DECEMBER 1999 CUNA & AFFILIATES

Level Two

NEW BANKThe City, MI 98765

Pay to the Order of(Order to Pay)

Remitter

(Payee's Name)

PAY EXACTLY $1,000 DOL 00 CTS

VOID AFTER 90 DAYS

Dollars

$

Date

4900892027

*1,000.00*

THIS DOCUMENT HAS AN ARTIFICIAL WATERMARK PRINTED ON THE BACK. THE FRONT OF THE DOCUMENT HAS A MICRO-PRINT SIGNATURE LINE. ABSENCE OF THESE FEATURES WILL INDICATE A COPY.

AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE

CASHIER'S' CHECK

NEW BANKThe City, MI 98765

Pay to the Order of(Order to Pay)

Remitter

(Payee's Name)

PAY EXACTLY $1,000 DOL 00 CTS

VOID AFTER 90 DAYS

Dollars

$

Date

4900892027

*1,000.00*

THIS DOCUMENT HAS AN ARTIFICIAL WATERMARK PRINTED ON THE BACK. THE FRONT OF THE DOCUMENT HAS A MICRO-PRINT SIGNATURE LINE. ABSENCE OF THESE FEATURES WILL INDICATE A COPY.

AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE

TELLER'S CHECK

PAYABLE THRUCredit Union (Payor Bank)

Figure 5.2 Cashier’s and Teller’s Checks

The Cashier’s Check

The Teller’s Check

Figure 5.2 shows examples of a cashier’s check and a teller’s check. These negotiableinstruments are similar in most respects. A cashier’s check is a check that a bank draws onitself. A teller’s check is a check that a bank draws on another bank. Note the “payablethrough” notation on the teller’s check. Keep in mind, for purposes of the UCC, creditunions are “banks.”

5-16 MODULE 1 DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS © DECEMBER 1999 CUNA & AFFILIATES

Level Two

NEW BANKThe City, MI 98765

Pay to the Order of(Order to Pay)

Remitter

(Payee's Name)

PAY EXACTLY $1,000 DOL 00 CTS

VOID AFTER 90 DAYS

Dollars

$

Date

4900892027

*1,000.00*

THIS DOCUMENT HAS AN ARTIFICIAL WATERMARK PRINTED ON THE BACK. THE FRONT OF THE DOCUMENT HAS A MICRO-PRINT SIGNATURE LINE. ABSENCE OF THESE FEATURES WILL INDICATE A COPY.

AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE

CASHIER'S' CHECK

NEW BANKThe City, MI 98765

Pay to the Order of(Order to Pay)

Remitter

(Payee's Name)

PAY EXACTLY $1,000 DOL 00 CTS

VOID AFTER 90 DAYS

Dollars

$

Date

4900892027

*1,000.00*

THIS DOCUMENT HAS AN ARTIFICIAL WATERMARK PRINTED ON THE BACK. THE FRONT OF THE DOCUMENT HAS A MICRO-PRINT SIGNATURE LINE. ABSENCE OF THESE FEATURES WILL INDICATE A COPY.

AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE

TELLER'S CHECK

PAYABLE THRUCredit Union (Payor Bank)

PAYABLE THROUGH NEW CREDIT UNIONAnywhere, WI 12345

• A “certified check” is a check accept-ed by the bank on which it is drawn (“acceptance” means the drawee bank’s signed agreement to pay the check as presented). §3-409(d).

Note: For an illustration of a cashier’s check and a teller’s check, see figure 5.2.

These types of checks are distin-guished from other types of drafts in that the drawee bank itself is responsible for

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-14

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

the payment of the item. In the case of a personal check, for instance, it is the drawer who has primary responsibility for its payment. Although a personal check is payable by the drawer’s bank, if the drawer does not have sufficient funds in his account at the bank to pay the instrument, his bank is under no duty to honor it. In the case of cashier’s checks, teller’s checks, and certified checks, the payable amount is a direct obligation of the bank that issues the instrument.

Because of the special nature of these types of instruments, the Code (in §3-312) provides a special procedure by which a person who loses one can get a refund of the amount of the check, with-in a reasonable period of time, and with-out the need for a court order — while at the same time providing built-in pro-tection for the issuing bank. Under this special procedure, the individual who claims the right to receive the amount of a cashier’s check, teller’s check, or certified check that was lost, destroyed, or stolen (known as the “claimant”) may provide to the issuing bank a claim to the amount of the check. The claim must include a “declaration of loss” — a written statement made under the pen-alty of perjury — which states that:

• Declarer lost possession of a check.

• Declarer is the drawer or payee (for certified checks) or the remitter or payee (for cashier’s checks and teller’s checks) of the check.

• Loss of possession was not the result of a transfer by the declarer or a lawful seizure.

• Declarer cannot reasonably obtain pos-session of the check because it was

destroyed, its whereabouts cannot be determined, or it is in the wrongful possession of an unknown person or a person that cannot be found or is not amenable to service of process.

The claim must describe the check with reasonable certainty, it must be received by the obligated bank in time for it to act on it before the check has been paid, and the claimant must provide reasonable identification if requested by the obligated bank. Refer to figures 5.3 and 5.4 for sample Declaration of Loss statements.

If all of these conditions are met, the claim becomes enforceable on the 90th day following the date of the check (for cashier’s checks and teller’s checks) or the date the check was certified (for certified checks). In the rare case where a claim is made after 90 days have elapsed, it is immediately enforceable.

Until the claim becomes enforceable, it has no legal effect — the bank may pay the original check to a person enti-tled to enforce payment who presents the item for payment without regard to the claim during the period in which the claim is not enforceable. If the check is not presented before the claim becomes enforceable, the bank is then under no duty to pay the check and must then pay the claim. If the check is presented by a Holder in Due Course(HIDC) after the bank has refunded the money to the claimant, the bank does have the option of paying the HIDC the amount of the item, at which point the claimant must then refund the payment to the obligat-ed bank. Note, however, that your credit union would be wise not to pay an HIDC in such a situation, as it is under no legal duty to do so. If the bank refuses to

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-15

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

pay the HIDC who presents a cashier’s check, teller’s check, or certified check after a claim has been filed and paid, the claimant (who is now holding the money) is under a legal obligation to pay the amount of the check to the HIDC.

Limitations of special section. It is important to note that only the drawer or payee of a certified check or the remittor or payee of a cashier’s check or teller’s check is entitled to make a claim under §3-312. As the comment makes clear, an endorsee of a check is not covered by this section because the endorsee is not an original party to the check, nor is she a remittor. Limitation of this spe-cial section to claims made by original parties or remittors gives the obligated credit union the ability to determine the identity of the persons who could assert a claim with respect to the check — the credit union is not put into the posi-tion of having to determine the rights of some third party with whom the credit union had not dealt, and would have no way of ascertaining. If a cashier’s check is purchased to the order of the person purchasing it, and that person later indorses it over to a third person who then loses the check, the third person may assert rights to enforce the check under the more cumbersome — and expensive — process of filing a lawsuit to enforce a lost or stolen instrument, as discussed above with respect to §3-309.

From a practical standpoint, it is important to remind tellers not to cash teller’s and cashier’s checks drawn on their credit unions if they are more than 90 days old. When a member submits a Declaration of Loss, it becomes a valid claim against the credit union on the 90th day as discussed. If after paying

such a claim a Holder in Due Course presents the original instrument for pay-ment (for example, more than 90 days after it was issued) and the teller cashes it, the credit union could well be out the money.

Wrongful refusal to honor a cashier’s check, teller’s check, or certified check

§3-411 provides potentially severe penalties for a credit union that wrong-fully refuses to pay a cashier’s check, teller’s check, or certified check. If a credit union wrongfully refuses to honor one of these instruments, the person claiming the right to payment is entitled to compensation for expenses and loss of interest resulting from the nonpay-ment. Further, if the person entitled to payment provides notice to the obligated credit union that he may incur additional damages, the obligated credit union may be required to pay those additional (known as “consequential”) damages as well. Those consequential damages could include reasonable attorney fees and court costs associated with the col-lection of the item. The important moral to this story: credit unions should not lightly place stop payments on their cashier’s checks, teller’s checks, and certified checks.

Accord and satisfaction by use of instrument

Under common law, if a debtor had a good-faith dispute with a creditor about the amount owed on a debt, he could offer to settle the debt for less than the amount the creditor believed was owed by presenting the creditor with a check marked “payment in full” (or words to a

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-16

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

Figure 5.3 Sample Declaration of Loss of Certified Check

DECLARATION OF LOSS OF CERTIFIED CHECK

Date: _______________

Claimant’s Name: ___________________________________________________________________

Claimant’s Address ___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

Certified Check No. _______________

Date Date check of check: _______________ certified:_______________

Amount of check: _______________

Payable to ___________________________

Drawer’s Name ___________________________

Under penalty of perjury, I hereby swear:

1. That I lost possession of the above referenced check.

2. That I am the (circle one) drawer / payee of the above referenced check.

3. That the loss of possession of the above referenced check was not the result of a transfer by me or a lawful seizure.

4. That I cannot reasonably obtain possession of the check because (check one):

____ it was destroyed.

____ its whereabouts cannot be determined.

____ it is in the wrongful possession of an unknown person or a person that cannot be found or is not amenable to service of process.

_____________________________

Signature of Claimant

Figure 5.3 is an example of a “Declaration of Loss” which should be used when a member loses a certi-

fied check. Once completed, this claim is enforceable on the ninetieth day following the date the check

was certified by the credit union. If ninety days have already elapsed when the claim is submitted, the

claim is immediately enforceable. Note: only drawers and original payees may submit this type of claim.

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-17

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

Figure 5.4 Sample Declaration of Loss of Cashier’s or Teller’s Check

DECLARATION OF LOSS OF CASHIER’S OR TELLER’S CHECK

Date: _______________

Claimant’s Name: ___________________________________________________________________

Claimant’s Address ___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

Certified Check No. ____________________________

Date of check: ____________________________

Amount of check: ____________________________

Payable to _________________________________________

Remitter’s Name _________________________________________

Under penalty of perjury, I hereby swear:

1. That I lost possession of the above referenced check.

2. That I am the (circle one) remittor / payee of the above referenced check.

3. That the loss of possession of the above referenced check was not the result of a transfer by me or a lawful seizure.

4. That I cannot reasonably obtain possession of the check because (check one):

____ it was destroyed.

____ its whereabouts cannot be determined.

____ it is in the wrongful possession of an unknown person or a person that cannot be found or is not ame-nable to service of process.

_____________________________

Signature of Claimant

Figure 5.4 is an example of a “Declaration of Loss,” which should be used when a member loses a

cashier’s or teller’s check. Once completed, this claim is enforceable on the ninetieth day following the

date on the check. If ninety days have already elapsed when the claim is submitted, the claim is immedi-

ately enforceable. Note: only remittors and original payees may submit this type of claim.

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-18

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

similar effect). If the creditor accepted the check, it had in effect agreed to accept the lesser amount as payment in full. This doctrine was and is known as “accord and satisfaction,” and it is codi-fied in Article 3. Under this doctrine, a creditor can always send the check back to the debtor if it is not satisfied with the proposed settlement.

Through the years, some courts allowed creditors a way around a debt-or’s attempt at accord and satisfaction by using words such as “without preju-dice” or “with reservation of rights” in their endorsements. §3-311 of Revised Article 3 makes clear that creditors may not subvert an attempt at accord and satisfaction using such tactics. Acceptance of a check presented as pay-ment in full of an obligation, regardless of how the creditor endorses the instru-ment, serves as the creditor’s accep-tance of the debtor’s offer.

There are a few very important points to bear in mind on this score, however. In order to settle a debt through accord and satisfaction, a debtor must in good faith raise a bona fide dispute to the amount owed. Suppose, for example an insurance company sends a check to an insured as settlement for a claim for personal injury in an accident which is clearly covered by the insurance policy. Suppose the check is only a fraction of the full amount of the insured’s cover-age, but he is in need of the funds, so he cashes the check. If a court determines that the insurance company was tak-ing unfair advantage of the insured, the insured’s cashing of the check would not result in an accord and satisfaction, because the insurance company was not acting in good faith.

Also, given advances in technol-ogy with regard to the check collection system, the Code recognizes that many types of businesses routinely handle hundreds or thousands of payments from customers. In most cases, payments are processed through an automated process which cannot detect any special “payment in full” language on a check. §3-311 allows creditors to notify debtors that any payments sent with “paid in full” notations must be sent to a specific address, to allow the creditor to manu-ally process them. Alternatively, a credi-tor which has inadvertently accepted a payment in accord and satisfaction can send the payment back to the debtor within 90 days of its acceptance and thereby “undo” the accord and satisfac-tion. §3-311(c).

Part 4 — Liability of partiesSignature

Generally speaking, an individual is not liable on an instrument unless her signature appears on the instrument, or if she is represented by an agent or rep-resentative who signed the instrument on her behalf. §3-401 and §3-402. In the latter case, the agent or representa-tive is generally not liable on the instru-ment if that signature unambiguously shows that it is made on behalf of the represented person. §3-402(b)(1). So, for example, if a credit union treasurer signs credit union checks “Jane Doe, Treasurer, XYZ Credit Union,” XYZ credit union is liable on the instrument, not Jane Doe (a provision which should pro-vide credit union treasurers and manag-ers some measure of comfort).

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-19

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

Impostors, fictitious payees, forgeries and the like ...

Forgeries, alterations of instruments, impostors, and the like present difficult problems in negotiable instruments law and as such have been the subject of a great deal of litigation. These situations tend to create a loss which some inno-cent party will likely be required to bear, unless, of course, the “bad guy” can be apprehended. Since nobody yearns to bear the loss when they’ve not contrib-uted to its cause, these matters tend to frequently wind up in courts. Both Articles 3 and 4 attempt to fairly resolve disputes which can arise between various parties to a negotiable instrument which becomes part of a scheme to defraud.

As we will discuss in further detail below, Article 4 generally prohibits a credit union from paying an item that is not “properly payable.” By definition, an item which includes a forged signature or an unauthorized alteration is not properly payable. Hence, credit unions and other financial institutions bear a great deal of the risk of loss involved in these types of bogus instruments. This is not to say that credit unions and banks must always be left holding the bag. Financial institutions do have rights in these situations. The extent of those rights depends on the spe-cific nature of the forgery or alteration.

Take, for instance, the case of a drawer forgery. Typically this would arise when a credit union member’s checkbook was lost or stolen, and an individual forged the member’s name on a check as its drawer. If the member notifies the credit union in time for it to withhold payment of the forged item (or items) the credit union must, of course, not pay the items. But what if the items

are paid before the member realizes his checks were missing? As we will discuss further below, Article 4 provides the member a relatively short window — as little as 30 days, in some cases — after he receives the statement on which the stolen checks appear to notify the credit union that it has paid an item that was not properly payable. As long as the member contacts the credit union within that time frame, the credit union bears the loss for the item (under Article 4, it may be possible for the credit union to shift that loss to another financial institution or other innocent party who presented the item — we will discuss the time frames within which the credit union can accomplish this in our discus-sion of Article 4).

Article 3 creates a different outcome in the case of endorsement forgeries. Each party who endorses an instrument makes under §3-416 and §3-417 cer-tain warranties (known as “transfer war-ranties” and “presentment warranties”). Among those is a warranty that there are no unauthorized or missing endorse-ments on the instruments. If it later turns out that there was, indeed, a fraud-ulent endorsement, then the endorser who presented the item to the drawee bank for payment has breached this war-ranty and the drawee bank is entitled to return the item to — and be reimbursed by — that party. Each endorser on an instrument makes the same warranties; thus in the typical forged endorsement case, each succeeding endorsee can send the check back down the line, recovering on the warranties made by prior endorsers, until ultimately the check winds up in the hands of the indi-vidual who dealt directly with the forger.

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-20

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

Any breach of warranty claim must be asserted generally within 30 days after the drawee learns of the breach and the identity of the person who negotiated the item. §3-417.

The “Impostor Rule.” In certain situ-ations, the accountholder must bear the loss for a fraudulent endorsement. The first of these is what is referred to as the “Impostor Rule.” Suppose an individual (call him Mr. X) poses as the agent of another person, Mr. Y. Suppose further that the drawer writes a check, makes it payable to Mr. Y, but turns it over to Mr. X. Then suppose Mr. X signs Mr. Y’s name and deposits the item into the banking system. In this scenario, the drawer cannot later assert that the item was not properly payable and, therefore, he is on the hook. §3-404(a).

The fictitious payee. The second situ-ation in which the accountholder must bear the loss for a fraudulent endorse-ment involves a “fictitious payee.” Here the drawer or one of his agents or employees prepares a check pay-able to a named payee, but he does not intend that the payee will ever receive the check. Suppose, for example, Mr. A, who is an employee of Mr. B, prepares a check drawn on Mr. B’s company account, payable to Mr. C. But instead of forwarding the check on to Mr. C, Mr. A forges Mr. C’s endorsement and cash-es it. Here Mr. B must bear the loss on this item unless, of course, he can find and collect from Mr. A. §3-405.

In general, if a bank in good faith pays an instrument based on the fraudu-lent endorsement of an employee of the drawer who has been entrusted with “responsibility” with respect to any instrument, the endorsement is effec-

tive as the endorsement of the person to whom the instrument is payable if it is made in the name of that person. Of course, if the bank which pays the instrument fails to exercise ordinary care in paying the item, and that failure substantially contributes to loss result-ing from the fraud, the person bearing the loss (in our case, Mr. B) can recover from the bank. §3-405(b).

The Code provides a very specific meaning to the term “responsibility” as used above. “Responsibility” with respect to an instrument means authority to:

• Sign or endorse instruments on behalf of the employer.

• Process instruments received by the employer for bookkeeping purposes, for deposit to an account, or for other disposition.

• Prepare or process instruments for issue in the name of the employer.

• Supply information determining the names or addresses of payees of instruments to be issued in the name of the employer.

• Control the disposition of instru-ments to be issued in the name of the employer.

• Act otherwise with respect to instru-ments in a responsible capacity. §3-404(a)(3).

Note: an employee does not have “responsibility” with respect to an instrument merely because he has access to it.

Negligence contributing to forged signature or alteration of instrument. A drawer can also find himself holding

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-21

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

the bag on an alteration if his own neg-ligence contributes to an alteration of an instrument that is later paid in good faith by his drawee bank. Consider the following example, which appears in the Comment to §3-406:

Example: A company writes a check for $10. The figure “10” and the word “ten” are typewritten in the appropri-ate spaces on the check form. A large blank space is left after both the figure and the word. The payee of the check, using a typewriter with a typeface simi-lar to that used on the check, writes the word “thousand” after the word “ten” and a comma and three zeros after the figure “10.” The drawee bank then in good faith pays $10,000 when the check is presented for payment and debits the account of the drawer in that amount.

As was discussed earlier, a bank is generally under a duty not to pay items unless they are properly payable. An item is, by definition, not properly pay-able if it is altered in an unauthorized fashion. The Code, however, provides an exception to this general proposition in situations such as these. If a court finds that the drawer failed to exercise ordinary care in writing the check and that the failure substantially contrib-uted to the alteration, the drawer may not claim that the bank paid an item that was not properly payable due to the alteration. In other words, if the drawer makes it too easy for the bad guys, the drawer may have to pay the price for his negligence.

Part 5 — DishonorPresentment, dishonor, and notice of dishonor

“Presentment” is defined in §3-501 to mean generally, with respect to a check, a demand that the drawee or other party obliged to pay an instrument make payment on it. Section 3-501(b)(1) provides a broad variety of present-ment options, including physical pre-sentment of the item at the credit union upon which it is drawn, or presentment “by any commercially reasonable means, including an oral, written, or electronic communication.” This helps speed the check collection process substantially, given advances in technology, as we will discuss below when covering Article 4.

Section 3-501 also allows a party to whom presentment is made to treat it as occurring on the next business day after the day of presentment if the party to whom presentment is made estab-lishes a cutoff hour not earlier than 2 p.m., and the presentment is made after the cutoff hour. As is addressed in more detail in our discussion of Article 4, this cutoff hour can have an impor-tant impact on a credit union’s ability to make timely returns of nonsufficient funds items.

Several rules govern the dishonor of checks. If a check is duly presented for payment to the payor credit union (except in the case of presentment for payment over the counter), the check is considered dishonored if the payor credit union makes a timely return of the check or sends timely notice of dishonor or nonpayment as required in Article 4. §3-502(b)(1). A draft is also considered dishonored if it is presented over the

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-22

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

counter for payment or for certification (“acceptance”), and the payor credit union refuses to pay it or certify it by the close of business on the date of present-ment. §3-502(b)(2).

If a check has been dishonored, Article 3 provides that an endorser of a check is liable to any subsequent transferees for payment of the check. §3-415. In addi-tion, §3-414 states that the drawer is obliged to pay an unaccepted draft if it is dishonored. These obligations, however, may not be enforced unless the endorser and drawer are given notice of dishonor of the instrument (unless notice is excused, as discussed below). §3-503(a). Notice of dishonor may be given by any com-mercially reasonable means — typically it is accomplished by returning the instru-ment to a credit union or bank for collec-tion. §3-503(b). Finally, if an instrument is taken for collection by a collecting bank, notice of dishonor must be given (a) by the bank before midnight of the next banking day following the banking day on which the bank received notice of dishonor; or (b) by any other person with-in 30 days following the day on which the person receives notice of dishonor. §3-503(c).

Excused notice of dishonor

As discussed above unless notice is excused, endorsers and drawers will be liable to pay an instrument if it is dishon-ored. Section 3-504 provides that notice of dishonor is excused if, by the terms of the instrument, no notice of dishonor is necessary to enforce the instrument or if the party whose obligation is being enforced waived notice of dishonor. This section also provides that any delay in giving notice of dishonor is excused if

the delay was caused by circumstances beyond the control of the person giv-ing the notice as long as that person exercised reasonable diligence after the cause of the delay ceased to operate.

UCC Article 4: Bank Deposits and Collections

To this point, we have been discuss-ing the law of negotiable instruments in general. As was briefly mentioned, the term “negotiable instrument” encom-passes a variety of items. For purposes of this manual, our concerns lie primar-ily with checks. So it is with all of the participants in what can be broadly referred to as the “banking system.” Article 4 of the UCC was drafted to bring uniformity to the laws of check collec-tion as they pertain specifically to the banking system.

Perhaps the Comment to §4-401 puts matters into the best perspective as fol-lows:

The great number of checks handled by banks and the countrywide nature of the bank collection process require uniformity in the law of bank collections. There is needed a uniform statement of the principal rules of the bank collection process with ample provision for flexibility to meet the needs of the large volume handled and the changing needs and conditions that are bound to come with the years. This Article meets that need.

In 1950, at the time Article 4 was drafted, 6.7 billion checks were written annually. By the time of the 1990 revision of Article 4, annual volume was estimated by the American Bankers Association to be about 50 billion checks. The banking system could not have coped with this increase in check

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-23

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

volume had it not developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s an automated sys-tem for check collection based on encoding checks with machine-readable information by Magnetic Ink Character Recognition (MICR). An important goal of the 1990 revision of Article 4 is to promote the efficiency of the check collection process by making the provi-sions of Article 4 more compatible with the needs of an automated system and, by doing so, increase the speed and lower the cost of check collection for those who write and receive checks. An additional goal of the 1990 revision of Article 4 is to remove any statutory barriers in the article to the ultimate adop-tion of programs allowing the presentment of checks to payor banks by electronic transmis-sion of information captured from the MICR line on the checks. The potential of these programs for saving the time and expense of transporting the huge volume of checks from depositary to payor banks is evident.

Uniform Commercial Code CommentSection 4-101

So, while Article 3 defines the rights between parties with respect to nego-tiable instruments in general, Article 4 is devoted to that rather large subset of transactions within the body of nego-tiable instruments — bank collection of checks. Simply put, Article 4 defines the rights between parties with respect to bank deposits and collections.

Consider Article 3 the appetizer, if you will, and Article 4 the main course of a gourmet dinner. This is not to diminish the importance of Article 3. It is the building block upon which Article 4 rests, and it is referenced throughout Article 4 by necessity.

Part 1 — General provisions and definitionsApplicability

Although it is called the “Uniform” Commercial Code, we know by now that there can be slight variations in the vari-ous provisions of the UCC from state to state. Ours is indeed a mobile society. Suppose a cherry farmer from Michigan meets a fruit wholesaler from Kentucky in Ohio and the two agree to a deal by which the wholesaler will purchase the farmer’s goods. Suppose the wholesaler pays for the cherries with a check drawn on her bank in Indiana. On her way back to Michigan, the farmer decides to deposit the check in a Chicago bank. Is the liability for the Chicago bank for whatever action or nonaction it takes with regard to that check controlled by the laws of Michigan, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, or Illinois? Section 4-102 answers the question: clearly Illinois law controls.

Section 4-102 provides that the liability of a bank for action or nonac-tion with respect to an item handled by it for purposes of presentment, payment, or collection is governed by the law of the place where the bank is located. §4-102(b). Given the mechanized sys-tem of bank collections now in place, the drafters of the Code found it impera-tive that one law govern the actions of any single bank.

In fact, had the farmer in our example deposited the check into a branch of her Chicago bank that was located in Michigan, §4-102(b) provides that the law of Michigan would apply because that is where the branch office is located. All of which is to say that Article 4 provides

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-24

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

a fairly clear answer to any questions of conflict of laws: look to the state in which the bank branch is located at which the item enters the payment system (for example, the “depositary bank”).

Variation by agreement; measure of damages; action constituting ordinary care.

Many of the provisions in Article 4 can be changed by agreement between parties. However, the parties are never allowed to disclaim a bank’s responsibil-ity when it has failed to exercise ordi-nary care or its duty to act in good faith. §4-103(a). It is also important to note that any Federal Reserve regulations and operating circulars or clearing-house rules are given, in §4-103(b), the effect of agreements which override the provi-sions of the UCC, whether or not they are specifically agreed to by all parties involved in the handling of an item. Thus Federal Reserve regulations, operat-ing circulars, and clearinghouse rules supersede Article 4 whenever they are in conflict.

It is important to note that various sections of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. §221 et seq.) authorize the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System to direct the Federal Reserve banks to exercise bank collection func-tions. For example, Section 13 of the Act (12 U.S.C. §342) authorizes the Board to require each Federal Reserve bank to receive deposits from nonmember banks solely for the purposes of exchange or of collection. Under this statutory authoriza-tion, the Board has issued Regulation J, which is discussed in the next chapter. Another federal statute, the Expedited Funds Available Act (12 U.S.C. 4007(b))

provides that the EFAA and Regulation CC (12 C.F.R. 229) supersede any provi-sion of the law of any State, including the Uniform Commercial Code, which is inconsistent with the EFAA and Regulation CC.

Definitions

In order to assist in understanding the workings of Article 4, it is useful to clarify the definition of the participants in the check collection system. §4-105 provides definitions for these basic terms as follows:

• Bank means a person engaged in the business of banking. The term includes, among other things, a credit union. As mentioned above, although credit unions and banks tend to prefer to distinguish themselves from one another, in the context of the UCC it is beneficial to treat them as the same.

• Depositary bank means the first bank to take an item even though it is also the “payor bank”, unless the bank is the payor bank and the item is presented for immediate payment over the counter.

• Payor bank means a bank that is the drawee of a draft.

• Intermediary bank means a bank to which an item is transferred in course of collection except the depository or payor bank.

• Collecting bank means a bank han-dling the item for collection except the payor bank.

• Presenting bank means a bank pre-senting an item except a payor bank.

Natural person credit unions will

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-25

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

almost always find themselves in the role of either “depositary banks” or “payor banks” in this scheme.

These definitions should be borne in mind throughout the remainder of this chapter, as the various rights, duties, and responsibilities assigned the vari-ous participants in he check collection process can differ depending on how a particular entity is classified. For exam-ple, some checks are made “payable through” a particular bank. That lan-guage makes the named bank a “collect-ing” bank, not a “payor” bank. §4-106.

The huge volumes of checks processed each day must go through a series of accounting procedures, each of which consume time. As it is in many aspects of commerce, time is of the essence in the check collection arena. As such, §4-108 provides a little breathing room for the participants. It provides that a bank may fix an afternoon hour of 2 p.m or later as a cutoff time after which deposits received will be considered to be made at the opening of business on the next bank-ing day. Note, however, that Regulation CC includes special provisions by which credit unions must notify their members if they choose to establish such a cutoff.

Statute of limitations

Claims by various parties against each other under the UCC can arise in many different ways as we have already seen. Generally, the Code requires that any claims be made promptly. Participants in the check collection system tend to promptly report and pay valid claims, because the entire credibility of the bank-ing system depends upon prompt settle-ment. In some cases, however, there will inevitably be a dispute between partici-

pants. Under the 1990 amendments to Article 4, a new section was added to pro-vide that a suit to enforce claims under Article 4 must be brought within three years after the claim first arose. §4-411. Thus, for the first time the Code has standardized the statute of limitations for claims brought under this article.

Part 2 — Collection of items: depositary and collection banks

We’ve already discussed the general world of negotiable instruments above. As we’ve seen, negotiable instruments are quite useful in the conduct of commerce particularly when all of the players in the system can be reasonably sure of their rights and responsibilities.

In the typical buyer-seller transaction, the buyer will pay for her goods using a negotiable instrument, the vast majority of those being checks. Given their nego-tiable nature, those checks can then, in turn, be negotiated in further transac-tions, conceivably until there is finally no room left on the check for further endorsements. Throughout this process, Article 3 generally governs the rights, duties, and responsibilities of the parties.

Enter Article 4. But eventually, one of the parties will introduce the check into the realm of Article 4 by negotiating it in favor of a bank. From this point on, with some limited overlap with Article 3, Article 4 takes over.

The depositary bank, for example, the bank at which point the check enters the check collection system, is described as an agent or subagent of the owner of the item and any settlement given for the item is provisional. §4-201(a). In other words, when a credit union member

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-26

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

cashes or deposits a check, the credit (whether in the form of cash or a depos-it) is provisional until final payment is made on the item. This is true regard-less of the form of endorsement on the check. It is not always easy from the depositor’s end to know when settlement on an item becomes final. As we will discuss below, payor banks have specific time frames within which they must dis-honor a check, or it is considered paid. But the Code does not then require that any notice be made that an item was, in fact, paid. Considering the millions of checks which successfully clear bank and credit union accounts on a given day, it would be chaotic to require any kind of notice of final payment. Happily, the vast majority of instruments are paid as designed; therefore the code adopted a sensible “no news is good news” approach in this regard.

In the event that an item for which provisional credit is given is eventu-ally dishonored, the Code provides the depositary bank with the right to revoke the provisional settlement. §4-214(a).

An item is finally paid by a payor bank when the bank has either paid the item in cash; settled for the item without having a right to revoke the settlement under statute, clearinghouse rule, or agreement; or made a provisional settle-ment for the item and failed to revoke the settlement in the time and manner permitted by statute, clearinghouse rule, or agreement. §4-215.

Example: To help illustrate the cover-age of various articles in the UCC, let’s consider a transaction between two parties, call them Smith and Jones, to a transaction in which Jones, a mem-ber of XYZ Credit Union, agrees to pay

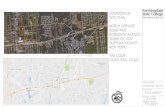

Smith, a member of ABC credit union, on a contract for the sale of goods. The underlying contract for the sale of goods is strictly between Smith and Jones, and is governed by Article 2 of the Code. The method of payment selected by the parties brings Article 3 into the picture. After Jones pays Smith with a personal check drawn on XYZ Credit Union, let’s assume Smith brings the check to ABC Credit Union for deposit. At this point, Article 4 enters the picture. Article 4 then governs the series of transfers of the check from ABC Credit Union (a “bank” for purposes of the UCC) through various intermediary banks, until it is presented for payment to XYZ Credit Union. Figure 5.5 illustrates this process.

Timely action by collecting banks

Section 4-202 of Article 4 imposes a duty on collecting banks to exercise ordi-nary care in all of the following:

• Presenting an item or sending it for presentment.

• Sending notice of dishonor on nonpay-ment or returning an item to the bank’s transferor after learning that the item has not been paid.

• Settling for an item when the bank receives final settlement.

• Notifying its transferee of any loss of delay in transit within a reasonable time after discovering it.

That section goes on to state that a collecting bank exercised ordinary care by taking proper action before its midnight deadline following receipt of an item, notice, or settlement. The midnight dead-

© 2018 CUNA DEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS 5-27

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4

Figure 5.5 Applicability of UCC

Smith & Jones Form Contract for Sales of Goods

Article 2, Sales, assigns rights and duties between Smith & Jones