Science-2013-799

-

Upload

shawn-stevens -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

0

Transcript of Science-2013-799

-

8/12/2019 Science-2013-799

1/1www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 340 17 MAY 2013

NEWS&ANALY

CREDITS(TOPTOB

OTTOM):MAXPLANCKINSTITUTE

FOREVOLUTIONARYANTHROPOLOGY;BENCEVIOLA,

MPI-EVA

COLD SPRING HARBOR, NEW YORKIn

2010, a girls pinkie bone from Denisova Cave

in Siberia added a new branch to the human

family tree. The bone was so well preserved

that researchers could fully sequence its

genome and glimpse the DNA of archaic peo-

ple now called Denisovans (Science, 28 Janu-

ary 2011, p. 392; 26 August 2011, p. 1084).

Now, researchers have analyzed three more

samples from that same cave using a power-

ful new method that reveals ancient genomes

in brilliant detail. One sample, a Neander-

tal toe bone, has yielded a nearly complete,

high-coverage genome of our closest cousins,

paleogeneticist Svante Pbo from the Max

Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropol-

ogy in Leipzig, Germany, reported at a meet-ing here last week.*

The analyses paint a complex

picture of mingling among ancient

human groups, Pbo reported. The

data suggest inbreeding in Nean-

dertals, a large Denisovan popula-

tion, and mixing between Deniso-

vans and an even earlier mystery

species. Its wonderful; amazing,

says Eric Lander, director of the

Broad Institute in Cambridge, Mas-

sachusetts. It opens up a vista on

the past world.Neandertals, the closest known

relatives to modern humans, ranged

across Europe to western Asia

from perhaps 300,000 years ago

until about 30,000 years ago. Their

overlap in time and space with our

ancestors had fueled debate about whether

the two species had interbred. Then, in 2010,

Pbos group published a low-coverage

sequence (1.3 copies on average) of DNA

from three Neandertal bones from Croatia,

which showed interbreeding: About 2% of

the DNA in living people from outside Africa

originally comes from Neandertals (Science,7 May 2010, pp. 680 and 710).

That first Neandertal sequence was a huge

accomplishment, as Neandertal DNA made

up just a few percent of the DNA in the fos-

sils, the rest being bacterial and other con-

taminants. Since then, the Leipzig group has

found ways to zero in on human genetic mate-

rial and to get more from degraded ancient

DNA by using a sequencing method that

starts with single, rather than double, strands

of DNA. The approach provided a startlingly

detailed view of the Denisovan pinkie bone

(Science, 31 August 2012, p. 1028).

But this powerful technique had yet to be

applied to Neandertals. So Pbo was thrilled

when the DNA in the sample taken from the

toe bone proved to be 60% Neandertal. The

researchers were able to sequence each base

50 times over, on averageenough cover-

age to ensure the sequence is correct. This

approach also provided low coverage of the

genome from another fossil, a Neandertal

babys rib, more than 50,000 years old, from a

cave in Russias Caucasus region between the

Caspian and Black seas.

In a 10 p.m. talk to a full house, Pbo

offered some surprising results from the toe

bone. For long stretches, the DNA from each

parental chromosome is closely matched,

strongly suggesting that this Neandertal was

the offspring of two first cousins, he said.

Comparing the data with those from the fos-

sils from Croatia and the Caucasus showed

that these populations were fairly separatedfrom one another. The group also compared

the chunks of Neandertal DNA found in liv-

ing people with each of these three Nean-

dertal samples. The closest match was with

the Caucasus population, suggesting that

interbreeding with our ancestors most likely

occurred closer to that region.

From the detailed genomes of both Nean-

dertals and Denisovans, Pbo and Montgom-

ery Slatkin of the University of California,

Berkeley, estimated that 17% of the Deniso-

van DNA was from the local Neandertals. An

the comparison revealed another surprise

Four percent of the Denisovan genome come

from yet another, more ancient, human

something unknown, Pbo reported.Get

ting better coverage and more genomes, yo

can start to see the networks of interaction

in a world long ago, says David Kingsley, an

evolutionary biologist at Stanford Universit

in Palo Alto, California.

With all the interbreeding, its more a net

work than a tree, points out Carles Lalueza

Fox, a paleogeneticist from the Institute o

Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, Spain

Pbo hesitates to call Denisovans a distinc

species, and the picture is getting more com

plicated with each new genome.

Pbos team also deciphered additiona

Denisovan DNA, both nuclear and mitochon

drial, from two teeth found in different layers i

Denisova Cave. The nuclear DNA confirme

that both teeth are Denisovan. But, surpris

ingly, one tooth showed more than 80 mitochondrial DNA differences from

both the other tooth and the pinki

bone. These Denisovans, who live

in the same cave at different times

were as genetically diverse as tw

living humans from different conti

nents and more diverse than Nean

dertals from throughout their range

says Susanna Sawyer from Pbo

lab. Such diversity implies that th

Denisovans were a relativel

large population that at som

point may have outnumbereNeandertals, Pbo said.

In addition, the genome

are clarifying genetic change

that underlie our own evolu

tion. We will be able to know

all the changes that are ances

tral, Lalueza-Fox says. Pbo and his col

leagues have lined up the chimp, moder

human, Neandertal, and Denisovan genome

to see whats unique to our species. The cat

alog includes 31,000 single-base changes

which led to 96 protein changes, and mor

than 3000 changes in regulatory regions, a

well as 125 small insertions and deletionsPbo reported.

Peter Sudmant from the University o

Washington, Seattle has already begun scan

ning the Neandertal genome for uniquely

human duplications and deletions. Its some

thing we thought we would never be able t

do, he says. Adds Kingsley: It will tak

a long time to figure out the real causativ

events and figure out what traits they contro

but its a finite list.

ELIZABETH PENNIS

More Genomes From Denisova CaveShow Mixing of Early Human Groups

H U M A N E V O L U T I O N

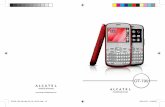

A cave for all people. Denisova Cave inSiberia yielded a Neandertal toe bone (inset) aswell as fossils of a new group of humans calledthe Denisovans.

*The Biology of Genomes, 7 to 11 May.

Published by AAAS