Saint-Denis Abbey: Stained Glass

Transcript of Saint-Denis Abbey: Stained Glass

Swarthmore College Swarthmore College

Works Works

Art & Art History Faculty Works Art & Art History

1996

Saint-Denis Abbey: Stained Glass Saint-Denis Abbey: Stained Glass

Michael Watt Cothren Swarthmore College, [email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-art

Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons

Let us know how access to these works benefits you

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation Michael Watt Cothren. (1996). "Saint-Denis Abbey: Stained Glass". The Dictionary Of Art. Volume 27, 548-549. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-art/103

This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art & Art History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected].

548 Saint-Denis Abbey, §11, 2(ii): Tomb sculpture, after c. 1500

St Andre-des-Arts, Paris, Louis XIII (including four cherubs by Jacques Sarazin), Louis XIV (the King was depicted on a medallion by Franpois Girardon, surrounded by mourners executed by Hubert Le Sueur and trophies by Etienne Le Hongre) and Louis XV (represented by a sole surviving fragment—a ChariPf sculpted by Jean- GuiUaume Moitte), as well as a marble bust of Louis AV7/7executed by AchiUe Valois (1785-1862).

BIBLIOGRAPHYLi Rot, la sculpture et la mort: Gisants et tomheaux de la basilique de Saint-

Denis (exh. cat. by A. Erlande-Brandcnburg and others, Saint-Denis, Maison Cult., 1976) [with earlier bibliog.]

G. Bresc-Bautier: Tombeaux factices de Pabbatiale de Saint-Denis ou Part d’accommoder les testes’. Bull. Sot. N. Antiqua. France (1980-81), pp. 114-27

B. Hocbsteder Meyer: ‘Jean Perrealand Portraits of Louis XII’,/. Walters ^.G;,xl(1982),pp. 41-56

----- : ‘Leonardo’s “Batde of Angbiati”: Proposals for Some Sources anda Reflection’, A. Bull., Ixvi (1984), pp. 367-82

C. Grodecki: Documents du minutier central des notaires de Paris: Histoire de I'artauXVLe siecle, 1540-1600, ii (Paris, 1986)

PHILIPPE ROUILLARD

III. Stained glass.Little remains of the abbey’s important and influential medieval glazing. The windows of the Rayonnant choir and nave, probably the most important 13th-century ensemble in the Paris region before the glazing of the Sainte-Chapelle, were destroyed in the Revolution. They are documented only in a sketch, one of a series (Com- piegne, Mus. Mun. Vivenel) made in 1794-5 by Charles Percier, and the reliability of even this has been challenged

(LiUich). Despite the effects of the Revolution and a series of 19th-century restorations, more glass, and better documentation, survive from the ambulatory of Suger’s 12th- century church, enabling some evaluation of Ae significance of this glazing within the history of medieval art.

Glazing played an unprecedentedly influential role in the design of Suger’s church, especially in the ambulatory. Here for the first time stained glass became an important feature, perhaps the most important feature, of an architectural environment. In Suger’s record of his administration, some of his most rhapsodic commentary praises the pervasiveness of coloured light in the building. He describes the manner in which the choir shone ‘with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most sacred windows, pervading the interior beauty’ (Panofsky, p. 101). Suger admired the windows not principally for their beauty but for the way in which their luminosity could help the viewer to approach God through the contemplation of light.

These windows survive only in fragmentary condition. Although most of the glass was spared during the Revolution, what survived soon left the abbey for Alexandre Lenoir’s Musee des Monuments Franpais in Paris. Numerous unexhibited panels were sold but those included in the museum were returned to the abbey in 1817-18. Most remained to be transformed in two heavy-handed restorations, incorporated within the mid-19th-century neo-Gothic windows now in the ambulatory. Some of the best-preserved panels are now in European and American museums (e.g. Bryn Athyn, PA, Glencairn Mus.; Champs- sur-Marne, Chateau; Glasgow, Burrell Col.; London, V&A; Paris, Mus. Cluny; Raby Castle, Durham). All the remains considered in conjunction facilitate the reconstruction of the design and stylistic character of the most prominent windows, and a partial assessment of the original iconographic programme.

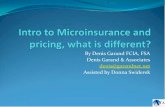

Suger refers to the Jesse Tree window by name and describes the Moses and ‘Anagogical’ windows in some detail. Fortunately, portions of all three have survived at the abbey. The ‘Anagogical’ and Moses windows (now in the St Peregrinus Chapel) must have originally formed a diptych occupying both openings of a single chapel, as they do today. The former outlines an allegorical means of interpreting Old Testament events in the light of New Testament truths, an ‘Anagogical’ method apparently devised by Suger from the writings of St Paul, with the purpose of urging the viewer, as he says, ‘onward from the material to the immaterial’. In the adjacent window {see Stained glass, fig. 8), this method is employed in presenting the life of Moses, the interpretative burden resting heavily on rather lengthy inscriptions. The personal iconographic statements represented in these windows were each unique. The Jesse window, however, initiated a long series of a similar design portraying this royal and prophetic genealogical theme. At Saint-Denis the Jesse window again seems to have formed one wing of an iconographic diptych, this one concentrating on the Incarnation and presumably installed originally, as now, in the axial Virgin Chapel. The companion window, devoted to the Infancy of Christ (see fig. 9), includes in Annunciation scene a portrait of Suger himself, prostrate at the

mit '/i''.- i ''''

I "'K

\f1\,H \ /*■ ?

f / h

9. Saint-Denis Abbey, Flight into Egupt, stained glass, 520x500 mm, detail from the Infancy of Christ window, e. 1140—45; ornamental border is modem (Bryn Athyn, PA, Glencairn Museum)

Virgin’s feet. Only three fragmentary scenes from this window remain at Saint-Denis, but the Percier drawings and ten other panels in public and private collections permit a full reconstruction of its original appearance.

In addition to these four windows with secure Sugerian associations, subjects depicted in two others from the ambulatory can be confidently identified: a St Benedict window, drawn by Percier, can be assembled from nine fragments in French and English collections (Christchurch, Dorset, Borough Council; Fougeres, St Leonard; Paris, Mus. Cluny; Raby Castle, Durham ;Twycross, Leics, St James). From a window devoted to the theme of crusading, two medallions have survived (Bryn Athyn, PA, Glencairn Mus.). Drawings of 12 comparable roundels, now lost, were published by Montfaucon in 1729. This window, however, may not have been installed until 1158, during the abbacy of Suger’s successor, Odo of Deuil.

As recorded by Suger, the windows were made by ‘many masters from different regions’ (Panofsky, p. 73). Two painters collaborated on both the Infancy and Crusading windows, and the hand of one of them can also be discerned in the ‘Anagogical’, Moses and Jesse Tree windows. They are most clearly differentiated through the use of quite distinct formulae for facial articulation. Moreover, one artist was a fussy painter, employing short, precise strokes to build up the considerable detail with which he executed all features of his compositions. His painting technique seems to coincide with the brittle angularity of his style. His collaborator used longer, broader, bolder and more fluid brushstrokes, which reinforce the confident, curvilinear economy of his style. A third seems to have been responsible for the St Benedict window. His fluid and assured painting is distinguished by the use of a facial formula mixing a bold, schematic outline with considerable detail of features (especially facial hair).

Saint-Denis Abbey, §IV; Treasury

The gracefully attenuated figural proportions and decorative richness of drapery patterns also separate his work from the squat, stiff, schematic figures used by the other two artists. The materials with which the artists worked are remarkably consistent from window to window, suggesting that they may have been members of a single workshop.

BIBLIOGRAPHYB. de Montfaucon: Les Monumens de la monarchiefranfoise, i (Paris, 1729),

pp. 277, 384-97, plsxxiv-xxv, 1-livE. Panofsky: Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis and its Art

Treasures (Princeton, 1946; ed. G. Panofsky-Soergel, rev. 2/1979), pp.73,101

L. Grodecki: ‘Les Vitraux allegoriques de Saint-Denis’, A Fr., i (1961), pp. 19-46

K. Hoffmann: ‘Sugers “Anagogisches Fenster” in Saint-Denis’, Wallraf- Richartoijb., xxx (1968), pp. 57-88

L. Grodecki: Les Vitraux de Saint-Denis: Etude sur le vitrail au Xlleme siecle, Corp. Vitrearum Med. Aevi (Paris, 1976)

___ : Tes Vitraux de Saint-Denis: Histoire et restitution, Corp. VitrearumMed. Aevi (Paris, 1976) [with references to earlier bibliog.]

----- : Le Vitrail roman (Fribourg, 1977), pp. 91-103J. Hayward: ‘Stained Glass at Saint-Denis’, The RoyalAbby of Saint-Dents

in the Time of Abbot Suger (exh. cat., ed, S. McK. Crosby and others; New York, Met., 1981), pp. 60-99

M. P. LiUich: ‘Monastic Stained Glass: Patronage and Style’, Monastiasm and the Arts, ed. T. G. Verdon (Syracuse, NY, 1984), pp. 207-54

E. A. R. Brown and M.W.Cothren: ‘The Twelfth-century Crusadit^ Window of the Abbey of Saint-Denis: “Praeteritorum enim recordatio futurorum est exhibitio”’ ['The recollection of the past is a guarantee of the future],/. Warb. & Court. Inst, xlix (1986), pp. 1^0

M. H, Caviness: ‘Suger’s Stained Glass at Saint-Denis: The State of Research’, Abbot Suger and Saint-Denis: A Symposium: New York, 1986, pp. 257-72

M. W. Cothren: ‘The Infancy of Christ Window from the Abbey of St- Denis: A Reconsideration of its Design and Iconography’, A. Bull., lxviii(1986),pp. 398-420

L. Grodecki: ‘The Style of the Stained Glass Windows of Saint-Denis , Abbot Suger and Saint-Denis: A Symposium: New York, I986,pp. 273-81 . , ,

M. W.Cothren: ‘Suger’s Stained Glass Masters and their Workshop at Saint-Denis’, Paris: Center of Artistic Enlightenment, ed. G. Manner and others. Papers in the History of Art from the Pennsylvania State University, iv (University Park, PA, 1988), pp. 46-75

___ ; ‘Is the Tlte Gerente from Saint-Denis?’,/ Glass Stud., xxxv (1993),pp.57-64

L. Grodecki: Etudes sur les vitraux de Suger d Saint Denis, Nile siecle. Corpus Vitrearum, France Etudes, iii (Paris, 1995)

MICHAEL W. COTHREN

IV. Treasury.The treasury of Saint-Denis was the richest in France. Known from inventories (abridged of 1504, detailed of 1534 and 1634) and the engravings of Felibien, it disappeared almost entirely at the Revolution, with the exception of the objects set aside in 1791 for the BibHotheque Nationale, Cabinet des MedaiUes and in 1793 for the Louvre.

As royal mausoleum and official custodian of the regalia, the abbey benefited continuously from gifts by the French sovereigns. Already mentioned by Gregory of Tours in the 6th century, the riches assembled round the tomb of St Denis were increased by the benefactions of King Dagobert (the cross of St Eligius; Paris, Bib. N.), of Pepin the Short (t¥^ 751-68), Queen Bertrade and especially Emperor Charles the Bald, who was lay abbot of the monastery from 867 to 877 (‘Escrin de Charlemagne (destr.), ‘Coupe des Ptolemees’, serpentine paten; Paris, Bib. N., and Paris, Louvre; cross, golden altar frontal.

549