Running head: IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 1 · Figure 4 2016 Patient Population by Age and Sex...

Transcript of Running head: IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 1 · Figure 4 2016 Patient Population by Age and Sex...

Running head: IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 1

A Quality Improvement Project: Implementing a Risk Index Tool to Guide

Naloxone Prescribing in Patients on Chronic Opioid Therapy

Peggie L. Powell

VCU School of Nursing – DNP Program

DNP Project Advisor: Holly Buchanan, DNP, ANP-BC

DNP Project Content Expert: Manhal Saleeby, MD

DNP Project Team Member: Juli J. Moseley, PharmD

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 2

Table of Contents

List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 4

List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 5

Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 6

Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 7

Problem Statement ......................................................................................................................... 8

Purpose ............................................................................................................................. 10

Clinical Question ...…………………............…….......................................................... 10

Review of the Literature .............................................................................................................. 11

Background and Significance ...................................................................................................... 22

Conceptual Framework .................................................................................................... 24

Needs Assessment ............................................................................................................ 25

Key Stakeholders ............................................................................................................. 31

Barriers and Facilitators ................................................................................................... 33

Benchmarks ...................................................................................................................... 34

Budget .............................................................................................................................. 35

Project Description........................................................................................................................ 37

Project Mission ................................................................................................................ 38

Goals and Objectives ....................................................................................................... 38

Outcome Measures ........................................................................................................... 39

Project Design .............................................................................................................................. 42

Methods ............................................................................................................................ 42

Potential Risks and Threats .............................................................................................. 49

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 3

Project Evaluation Plan ................................................................................................................ 50

Data Analysis Plan ........................................................................................................... 53

Discussion and Implications ........................................................................................................ 55

Clinical Implications ........................................................................................................ 56

DNP Essentials ................................................................................................................. 57

Quality and Safety ............................................................................................................ 57

Plan for Sustainability ...................................................................................................... 58

References .................................................................................................................................... 64

Appendix A Flow Diagram of the Search Process ................................................................... 71

Appendix B RIOSORD Tool used in the Veterans’ Health Administration ........................... 72

Appendix C RIOSORD Tool used in the Commercial Insurance Population ......................... 73

Appendix D Proposed DNP Project Budget ............................................................................. 74

Appendix E The Stetler Model of Research Utilization .......................................................... 75

Appendix F Example of a Naloxotel Comprehensive Progress Note ..................................... 76

Appendix G Example of a Naloxotel Prior Authorization Letter ............................................. 77

Appendix H Opioid Overdose Symptoms and Resuscitation Instructions ............................... 78

Appendix I Nurse Checklist for Naloxone Training ............................................................... 79

Appendix J Overdose Prevention Tips and Naloxone Resources ........................................... 80

Appendix K Proposed DNP Project Timeline .......................................................................... 81

Appendix L RIOSORD Provider Satisfaction Survey ............................................................. 82

Appendix M Relationship of the DNP Essentials to the DNP Project ...................................... 83

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 4

List of Tables

Table 1 Conversion of Opioid Dose to Morphine Milligram Equivalents ....................... 15

Table 2 Project Application of the Stetler Model of Research Utilization ...................... 25

Table 3 Benefits of DNP Project to Patients and Institution ............................................. 36

Table 4 DNP Project Goals and Objectives ...................................................................... 39

Table 5 Covariates Analyzed in the IMS RIOSORD Tool ............................................... 40

Table 6 Aligning Goals and Objectives with Outcome Measures .................................... 41

Table 7 Conversion of RIOSORD Score to Risk Class and Probability of Overdose or

Serious OIRD ....................................................................................................... 45

Table 8 Steps to Achieve Sustainability Objectives ......................................................... 61

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 5

List of Figures

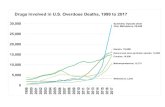

Figure 1 Comparison of prescription opioid sales and death rates ....................................... 9

Figure 2 Prescription opioid overdose deaths from 2001 to 2014 ..................................... 26

Figure 3 Distribution of the economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse,

and dependence .................................................................................................... 28

Figure 4 2016 Patient Population by Age and Sex ............................................................. 29

Figure 5 2016 Patient Population by Insurance .................................................................. 30

Figure 6 The different formulations of naloxone available to prescribe ............................ 48

Figure 7 The predicted probability (risk classes, by percentiles) versus observed incidence

of overdose or serious opioid-induced respiratory depression ............................ 52

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 6

Abstract

Background: Chronic pain and the treatment of chronic pain are challenges faced by healthcare

providers across the nation. Patients who take opioids for chronic pain significantly increase

their risk for serious opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) and overdose if they do not

take the medication as prescribed. Due to the rise in opioid overdose deaths, much attention is

focused on improving prescribing practices for opioid pain medication in the treatment of

chronic noncancer pain. A recommended risk mitigation strategy is to co-prescribe naloxone

when prescribing opioids for patients at high risk for overdose. Purpose: The purpose of this

project is to implement a validated risk assessment strategy that may reduce and/or prevent

overdose deaths from prescription opioids. Design: The project will utilize a prospective cohort

study design in which the Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-Induced Respiratory

Depression (RIOSORD) tool will be used to evaluate appropriate patients risk of overdose or

serious OIRD and examine how the tools use influences the prescribing practice of naloxone as a

rescue medication for patients on chronic opioid therapy. Outcome measures: Primary outcome

measures include the calculated RIOSORD score for each patient assessed, the number of high-

risk patients, and the number of naloxone prescriptions provided. Secondary outcome measures

include an analysis of the individual covariates from the RIOSORD tool. Implications:

Utilizing a validated, risk assessment tool to increase access to naloxone aligns well with the

national call for action to reduce opioid overdoses and promote safe opioid prescribing.

Keywords: chronic opioid therapy, overdose, naloxone, risk assessment

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 7

A Quality Improvement Project: Implementing a Risk Index Tool to Guide

Naloxone Prescribing in Patients on Chronic Opioid Therapy

Chronic pain and the treatment of chronic pain are public health challenges faced by

healthcare providers across the nation. Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts longer than

three months or past the time expected for normal tissue healing; chronic pain may be the result

of an underlying medical condition or disease, injury, inflammation, medical treatment, or an

unknown cause (Dowell, Haegerich, & Chou, 2016). For the purpose of this project, chronic

pain is used to reference chronic noncancer pain (CNCP).

It is estimated that over 100 million people in the United States suffer from chronic pain

and that chronic opioid therapy (COT) may be an appropriate treatment for some of these

chronic pain sufferers (Volkow, 2014). According to Dowell et al. (2016), evidence indicates

that short-term use of opioid pain medication is effective in reducing pain and improving

functional status in persons with noncancer nociceptive and neuropathic pain in randomized

clinical trials lasting ≤12 weeks. However, only a few studies have been conducted to rigorously

assess the long-term benefits of opioids (i.e., at least one year later) in patients with CNCP

(Dowell et al., 2016).

Despite the lack of evidence to support use of long-term opioid therapy in the

management of CNCP, its use has increased substantially in recent years and has been

accompanied by an increase in drug related deaths (Cheung et al., 2014; Volkow, 2014). From

1999 to 2014, more than 165,000 persons died from opioid overdoses in the United States

(Dowell et al., 2016). Manchikanti et al. (2014) estimate that Americans consume 99% of the

world’s supply of hydrocodone and 83% of the world’s supply of oxycodone. Prescription

opioid-related deaths have quadrupled in the United States since 1999 and approximately 80% of

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 8

these deaths are due to unintentional overdose (Rudd, Aleshire, Zibbell, & Gladden, 2016;

Zedler, Xie, et al., 2015).

Opioids are highly addictive in certain populations due to the release within the brain of a

naturally occurring neurotransmitter called dopamine. Dopamine creates pleasurable sensations

that are reinforcing for continued behavior (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2014).

This addictive nature of opioids makes them vulnerable to misuse and abuse (Cheung et al.,

2014). Patients who take opioids for chronic pain significantly increase their risk for negative

adverse events if they do not take the medication as prescribed (e.g., taking more than

prescribed, taking them by an alternate route, or taking them in combination with certain other

medications and/or alcohol). Opioids depress the central nervous system, which can result in

serious, life-threatening consequences such as sedation, respiratory depression, and potentially

death. The combined effects from alcohol and other medications significantly increase the risk

for overdose and death (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014).

Problem Statement

Overdose deaths have increased in parallel to prescriptions written for opioid pain

medication (Rudd et al., 2016; Dowell et al., 2016). Figure 1 demonstrates a comparison of

prescription opioid sales and death rates from 1999 to 2013. Dowell et al. (2016) note that

prescriptions written by primary care providers account for nearly half of all opioid sales. It was

also noted that opioid prescribing rates among healthcare providers increased 7.3% per capita

from 2007 to 2012 with rates increased more for family practice, general practice, and internal

medicine (Dowell et al., 2016). Overall, healthcare providers in the United States wrote 259

million prescriptions for opioids in 2012; this equates to one prescription for every adult in

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 9

America (Dowell et al., 2016). In 2014, overdose deaths from prescription opioids increased to

approximately 19,000 deaths in the United States; this is more than three times the number

reported in 2001 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA],

2016b). Considering the potentially fatal outcome of overdose, much attention is focused on

improving prescribing practices for opioid pain medication in the treatment of CNCP. Such

statistics are staggering and indicate the need for a call to action to reduce the opioid overdose

epidemic. These findings also demonstrate the importance of utilizing strategies to reduce or

prevent overdose deaths from prescription opioids in addition to recommendations for safe

opioid prescribing for those with chronic pain.

Figure 1. Comparison of prescription opioid sales and death rates. This chart

demonstrates a comparison of prescription opioid sales in relation to death

rates from opioid use during years 1999 through 2013.

Source: *Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System of the

Druge Enforcement Administration (2012 data not available); **CDC,

National Vital Statistics System mortality data, 2015.

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 10

Both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and SAMHSA recommend

that clinicians consider a co-prescription for naloxone when prescribing opioids for patients at

high risk of overdose as a risk mitigation strategy. Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that can

reverse respiratory depression and prevent death if administered in a timely fashion to a person

suspected of an opioid overdose. The CDC indicates that naloxone distribution programs are

associated with reduced risk for overdose death at the community level (Dowell et al., 2016).

Additionally, it is noted that friends and family are capable of administering naloxone once they

are properly educated and trained (Dowell et al., 2016; WHO, 2014).

Purpose of the Project

The purpose of this project is to implement a risk assessment strategy that may reduce

and/or prevent overdose deaths from prescription opioids. Specifically, this project will utilize a

validated risk assessment tool that quantifies a patient’s risk of overdose or serious opioid-

induced respiratory depression (OIRD) and examine how its utilization influences the

prescribing practice of naloxone as a rescue medication for patients on COT. The project will

also examine current naloxone prescribing patterns and potential factors influencing a provider’s

decision to co-prescribe naloxone prior to implementing a risk assessment tool. Additionally, the

project will assess provider satisfaction and ease of use. Implementing measures to improve

opioid prescribing practices supports the CDC’s goal for access to safe, effective pain treatment

while reducing risk for overdose (Dowell et al., 2016).

Clinical Question

The recommendation to prescribe naloxone for patients at increased risk of opioid

overdose raises the clinical questions of how to determine which patients are at increased risk

and how to measure risk of unintentional overdose in patients on COT. Neither SAMHSA nor

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 11

the CDC makes a recommendation for use of a specific tool. Available risk mitigation strategies

such as provider education, written opioid agreements, urine drug screens, prescription drug

monitoring programs, and screening for aberrant behavior may be beneficial in assessing for

misuse or abuse but they do not assess for or measure risk of overdose or OIRD. The only

published tool that provides an actual quantitative measure of overdose risk from opioid pain

medication is the Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression

(RIOSORD; Zedler, Xie, et al., 2015). Considering the increased use of COT to treat CNCP and

the subsequent rise in opioid-related deaths, the PICOT question addressed in this Doctor of

Nursing Practice (DNP) project is: Among providers who prescribe COT, does use of the

RIOSORD assessment tool, compared to not using a risk-screening tool, increase the prescribing

practice of naloxone over a six-month period?

Review of the Literature

Methods

Relevant literature was reviewed for evidence addressing the use of opioids to treat

chronic pain and available risk mitigation strategies to reduce misuse, abuse, and overdose. The

electronic databases utilized in the search process were PubMed, the Cumulative Index to

Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane Library, PsychInfo, and National

Guideline Clearinghouse. Key terms used in the search process were chronic opioid therapy,

overdose, naloxone, and risk assessment; these terms were combined utilizing the Boolean

operator “AND”. The search was limited to English language, peer reviewed journal articles,

and a publication date of 2011-2016. Studies were included if abstracts were available as well as

access to full text, were conducted within the United States, and limited to adults only. One

additional study was included based on the review of an article from the literature search. A total

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 12

of 613 records were identified, which was narrowed to 520 records after removing duplicates.

The titles and abstracts of the 520 articles were screened for inclusion. Articles were excluded (n

= 391) if they focused on specific opioid pain medications or illicit drugs; applied directly to

cancer-related pain, palliative care, or end of life; involved in-patient, hospital, or operative

settings; pertained directly to drug screening or testing; pertained to substance use disorder or

addiction; or involved pregnant women or children. A total of 129 full-text articles were further

reviewed for eligibility and 17 articles were included in this DNP project. Appendix A contains

a flow diagram of the search process. Common themes noted in the review of literature include

the use of opioid guidelines, the risk of overdose in relation to morphine-equivalent dose (MED)

and opioid formulation, and the use of risk instruments and other mitigation strategies such as the

SAMHSA toolkit and the RIOSORD tool to assess for aberrant behavior and risk of overdose.

Opioid guidelines. Opioid prescribing guidelines provide recommendations for

clinicians who prescribe opioids for persons with pain. However, multiple guidelines are

available and there is no consensus on which guideline clinicians should follow. In a systematic

review of available guidelines, Nuckols et al. (2014) note that recommendations provided by the

professional organizations American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine are

of high quality and are applicable to a broad range of adults with pain. Dowell et al. (2016) also

note that state and federal agencies such as the Washington Agency Medical Directors Group

(2015) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense (2010) provide their

own recommendations for opioid prescribing which are of good quality. Common elements

noted across most of these guidelines are recommendations for dosing thresholds and dosing

titration in addition to risk mitigation strategies such as the use of risk assessment tools,

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 13

treatment agreements, urine drug screenings, and the use of state prescription drug monitoring

programs (Dowell et al., 2016).

There is, however, considerable variability in specific recommendations such as the range

of dosing thresholds (MED of 90 to 200mg/day), the intended audience such as primary care

versus pain specialists, and the strength of the evidence upon which recommendations are based

(Cheung et al., 2014; Dowell et al., 2016). There is no clear consensus on a reasonable MED in

the treatment of CNCP but 100 to 120 mg morphine equivalents seems to be a reference level for

heightened caution due to evidence of increased morbidity and mortality at these doses (Cheung

et al., 2014). Recommendations from the CDC opioid guideline are directed at primary care

clinicians treating chronic pain and are based on a systematic review of the best available

evidence along with expert, public, and stakeholder input (Dowell et al., 2016). The literature

review performed by the CDC expanded upon a previously published systematic review

sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2014 on the efficacy

and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. Additional literature searches were

conducted to identify new studies and to update the existing review; there were 39 studies from

the AHRQ review and seven more studies from the updated review. Review of the evidence

sought to address five clinical concerns regarding the use of long-term opioid therapy to treat

chronic pain:

1. effectiveness and comparative effectiveness;

2. harms and adverse events;

3. dosing strategies;

4. risk assessment and risk mitigation strategies; and

5. effect of opioid therapy for acute pain on long-term use (Dowell et al., 2016).

The first four concerns were addressed in the previous 2014 AHRQ-sponsored systematic

review. However, the fifth concern was added for the purpose of developing the 2016 CDC

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 14

guideline and the updated systematic review was performed to address it. Thus,

recommendations from the CDC guideline provides guidance on determining when to initiate or

continue opioids for chronic pain; opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and

discontinuation; and assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use. Common factors

associated with an increased risk of opioid overdose identified by Dowell et al. (2016) include

the following:

use of extended-release or long-acting (ER/LA) opioid formulations;

MED >100mg/day;

a co-concurring prescription for benzodiazepines;

increased duration of opioid use;

the presence of sleep apnea or other sleep-disordered breathing;

renal and/or hepatic insufficiency;

older age (i.e., >65 years old);

pregnancy;

depression or other mental health conditions; and

alcohol or other substance use disorder(s).

Opioid prescribing guidelines are intended to promote safe opioid prescribing and to

improve patient outcomes. When making clinical decisions, prescribers are encouraged to

consider the patient-provider relationship in addition to the patient’s individual circumstances

including pain relief and benefit from COT; functional status and quality of life; medication side

effects; warning signs for addiction, abuse, or misuse; and any mood changes. These factors are

often referred to as the “five A’s” of analgesia therapy: activity, analgesia, adverse effects, and

aberrant behaviors, and affect (Agency for Clinical Innovation, n.d.).

Morphine-equivalent dose. Calculating the total daily dose of opioids helps to identify

patients who may benefit from closer monitoring, reduction of dose, prescribing of naloxone, or

other measures to reduce risk of overdose (CDC, 2016d). In order to calculate the total daily

dose, the clinician determines the dose of each opioid that the patient takes, converts dose(s) into

morphine milligram equivalents (MME) according to the CDC’s MME conversion factor in

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 15

Table 1, and then adds them all together. This conversion is referred to as the morphine

equivalent dose (MED) and is expressed as mg/day.

Higher doses of opioids are associated with an increased risk of overdose and death,

although some risk is associated even with relatively low doses (MED 20-50mg/day; CDC,

2016d). A randomized controlled trial conducted by Chou et al. (2015) found a significant

increase in risk of overdose when comparing MED 20-49mg/day to 200mg/day. The adjusted

odds ratio was 1.32 for MED 20-49mg/day, 95% CI [0.94, 1.84] compared to 2.88 for MED at

least 200mg/day, 95% CI [1.79, 4.63]. Another randomized controlled trial by Dowell et al.

(2015) found an adjusted odds ratio of 2.08 for MED 1-140mg/day, 95% CI [1.55, 2.78]

compared to 6.14 for MED ≥450mg/day, 95% CI [4.92, 7.66]. Nuckols et al. (2014) note that

Table 1

Conversion of Opioid Dose to Morphine Milligram Equivalents

Opioid Conversion Factor

Codeine 0.15

Fentanyl transdermal (in mcg/hr) 2.4

Hydrocodone 1

Hydromorphone 4

Methadone

1-20 mg/day 4

21-40 mg/day 8

41-60 mg/day 10

> 61-80 mg/day 12

Morphine 1

Oxycodone 1.5

Oxymorphone 3

Note. Doses are in mg/day except where noted.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016c,

August 25). Injury prevention & control: Opioid overdose,

guideline resources. Retrieved September 5, 2016, from

http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/resources.html

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 16

risk for serious or fatal overdose increased 1.9 to 3.1 fold with MED 50-100 mg/day and

increased even more dramatically with MED >100 to 200 mg/day. Two studies conducted by

Zedler indicated similar findings: odds ratio 4.96 for MED >100mg/day, 95% CI [3.24, 7.61]

(Zedler, Xie, et al., 2015) and odds ratio 4.1 for MED ≥100 mg/day, 95% CI [2.6, 6.5] (Zedler et

al., 2014). The CDC recommends prescribing the lowest effective dose, to “start low and go

slow”, and to avoid increasing to MED >90mg/day if possible. Morphine equivalent doses of

>50mg/day increase risk of overdose by at least two times the risk associated with <20mg/day

(CDC, 2016d).

Opioid formulations. The use of extended-release or long-acting opioid formulations is

associated with greater risk for overdose (Dowell et al., 2016; Zedler, Xie, et al., 2015). In a

2014 study conducted by Zedler et al., ER/LA opioid formulations were significantly associated

with increased risk of toxicity and overdose. Additionally, Nuckols et al. (2014) suggest that

only experienced clinicians prescribe methadone and that clinicians in general need to be aware

of risks associated with fentanyl patches. The CDC (2016d) notes that the MED conversion

factor for methadone increases at higher doses and absorption of fentanyl is affected by heat and

other factors such as patient weight. Sensitivity analysis by Wakeland, Schmidt, Gilson,

Haddox, and Webster (2011) suggests that the increase in opioid-related deaths may be related to

prescriber perception of reduced risk with use of long-acting opioids. Wakeland et al. (2011)

also suggest that prescriber education on the use of ER/LA opioids may be effective in reducing

opioid deaths, but little empirical evidence exists to support this finding.

Risk assessment tools. Various risk assessment tools are available to assess for aberrant

behavior in patients for whom opioids are prescribed or considered. These include the Opioid

Risk Tool (ORT), Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R),

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 17

Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), and the Chronic Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). A systematic

review by Nuckols et al. (2014) noted that the self-administered SOAPP-R and COMM

performed well in higher-quality observational studies for detecting aberrant behavior.

However, the CDC opioid prescribing guideline notes that there is insufficient evidence that the

use of such tools is beneficial in identifying risks associated with opioid overdose, abuse, or

addiction (Dowell et al., 2016). This recommendation is based on the variability of sensitivity

and specificity scores for each tool: ORT sensitivity 0.58-0.75 and specificity 0.54-0.86 in five

studies; SOAPP-R sensitivity 0.25 and 0.53 and specificity 0.62 and 0.73 in two studies, and BPI

sensitivity 0.73 and 0.83, specificity 0.43 and 0.88 in two studies (Dowell et al., 2016). It is also

important to note that results gained from the use of self-report questionnaire tools are subject to

the validity of the patient’s answers.

The aforementioned risk assessment tools identify patients at risk for aberrant behavior in

relation to opioid therapy but the tools do not measure the patient’s risk for overdose or

respiratory depression. Thus, tools that screen for overdose or serious OIRD are needed. The

retrospective study conducted by Zedler, Xie, et al. in 2015 indicates that patients at increased

risk of overdose or serious OIRD are likely to benefit from a co-prescription for naloxone as do

recommendations provided by SAMHSA (2016b) and the CDC (Dowell et al., 2016). The

RIOSORD tool is the only published tool that actually measures a patient’s risk for possible

overdose or OIRD. This tool is explored in more depth below.

Dowell et al. (2016) note that there is insufficient evidence that patient education, pill

counts, written treatment agreements, urine drug screens, or use of state prescription drug

monitoring programs are beneficial at mitigating risks but that most experts agree that co-

prescribing naloxone should be considered for patients at increased risk for overdose. Although

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 18

the effectiveness of treatment agreements, urine drug screenings, and use of state prescription

drug monitoring programs is not demonstrated in research studies to date, their use is

recommended by most opioid prescribing guidelines. Additionally, Nuckols et al. (2014)

indicate that such risk assessment tools are helpful in monitoring patients on COT and may be

beneficial in curbing abuse and misuse of opioids, which in turn reduces the risk of overdose.

The SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit and the RIOSORD tool are discussed below.

SAMHSA toolkit. In August 2015, the Virginia Department of Health issued a letter to

all clinicians encouraging adoption of the SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit. This

toolkit provides information for prescribers to use as recommendations to mitigate risks when

prescribing opioid pain medications in addition to expanding access to naloxone in Virginia

(Levine, Brown, & Ferguson, 2015). SAMHSA (2016b) stresses that healthcare providers can

reduce the toll of opioid overdose through the care they take in prescribing opioids and

monitoring the patient’s response, as well as by identifying and addressing overdose. SAMHSA

(2016b) identified five strategies for opioid overdose prevention:

encourage providers, persons at high risk, family members, and others to learn how to

prevent and manage opioid overdose;

ensure access to treatment for individuals who are misusing or addicted to opioids or who

have other substance use disorders;

ensure ready access to naloxone;

encourage the public to call 911; and

encourage prescribers to use state Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs.

As previously mentioned, SAMHSA recommend that clinicians consider a co-prescription of

naloxone for patients at high risk of overdose but no specific screening tool with which to

measure overdose risk is provided or recommended.

RIOSORD tool. Zedler, Xie, et al. developed the RIOSORD (i.e., Risk Index for

Overdose or Serious Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression) tool in 2015 using a retrospective,

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 19

case-control analysis of health care data from the Veteran’s Heath Administration (VHA)

inpatient and outpatient databases. Items included in the RIOSORD tool were selected from

variables found to have a statistically significant association with overdose or serious OIRD (see

Appendix B). Zedler, Xie, et al. (2015) found that the following factors are associated with an

increased odds ratio for overdose or OIRD: ER/LA opioid formulations, route of administration,

MED >100mg/day, and receipt of opioid prescriptions from multiple providers. These findings

are consistent with those identified in the CDC guideline as risk factors for overdose. Zedler,

Xie, et al. (2015) also notes that persons possessing the above-mentioned risk factors also

demonstrated greater health care utilization than controls. Variables with the most significant

positive associations were used to develop the RIOSORD tool: MED >100mg/day, history of

opioid dependence, hospitalization during the 6 months before the overdose or serious OIRD

event, liver disease, and the use of ER/LA opioids (Zedler, Xie, et al., 2015).

The RIOSORD tool provides a quantitative risk assessment for opioid overdose that is

evidence-based and is intended to provide clinical decision support. The tool demonstrated good

calibration and discrimination (i.e., predicted probability) between patients with and without

serious OIRD in the VHA population; the average predicted probability was 3% in the lowest

risk class and 94% in the highest (Zedler, Xie, et al., 2015). The personalized risk assessment

provided by the RIOSORD tool is useful in determining if an alternate medication, dose, or

formulation may reduce risk for OIRD; if clinical or behavioral recommendations are indicated;

or if a co-prescription for naloxone is recommended. The VHA sample included only men with

the majority being >55 years old. Hence, the validity of the results is unclear in other

populations such as younger patients, women, or those with commercial insurance. It is also

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 20

important to note that studies of the RIOSORD tool focused on the use of prescription opioids

and did not include use of heroin or opioids used for non-medical purposes.

Later in 2015, the original RIOSORD tool (VHA RIOSORD) was modified and further

validated in a retrospective, nested, case-control study of over 18 million patients from the

United States with a pharmacy claim for an opioid between January 1, 2009 and December 31,

2013 (Zedler, Saunders, Joyce, Vick, & Murrelle, 2015). This sample consisted of a much larger

population from the IMS PharMetrics Plus™ database of integrated commercial health plan

claims that is comprised of both medical and pharmacy claims. The objective of this study was

to validate and extend the RIOSORD tool in a larger population that is more representative of

medical users of prescription opioids in the United States (Zedler, Saunders, et al., 2015). The

IMS sample was deemed more representative because it included patients younger than 55 years

of age, females, and patients with commercial insurance in comparison to the VHA sample.

Zedler, Saunders, et al. (2015) found that the predictive performance of the revised RIOSORD

(IMS RIOSORD) in this large commercial insurance database was excellent and similar to the

VHA RIOSORD performance. The strongest predictors of overdose or serious OIRD in the IMS

population consisted of eight coexisting clinical conditions (e.g., neuropsychiatric disorders and

impaired drug metabolism or excretion) and eight characteristics of the prescribed opioid (e.g.,

specific medication characteristics and concomitant benzodiazepines or anti-depressants; Zedler,

Saunders, et al., 2015). Multivariable modeling of these covariates in the IMS population

demonstrated a C-statistic of 0.90, which indicates excellent discrimination between cases and

controls (Zedler, Saunders, et al., 2015).

The RIOSORD tool used in the commercial insurance population consisted of 16

questions with a total score of 146 points versus 17 questions with a total score of 115 points in

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 21

the VHA RIOSORD (see Appendix C). Covariates in the previously developed VHA RIOSORD

were modified as necessary to accommodate differences in the available commercial insurance

data population (Zedler, Saunders, et al., 2015). The total score in points corresponds with a risk

class that ranges from 1 to 7 with 1 being the lowest risk and 7 being the highest risk. The

average predictive probability of an event across the seven risk classes ranged from 2% in the

lowest risk class (0-4 points) to 83% in the highest risk class (>42 points; Zedler, Saunders, et

al., 2015). Patients identified as having increased risk for overdose or serious OIRD would

benefit from interventions to mitigate the risk of opioid overdose such as a co-prescription for

naloxone. Zedler, Saunders, et al. (2015) however, did not make a recommendation as to which

risk class she would start to consider a co-prescription for naloxone; instead, this decision is left

to the clinician that is prescribing the opioid. Nonetheless, use of the RIOSORD tool provides an

excellent opportunity to provide patient education regarding their individual risk of serious

OIRD.

Discussion

Misuse and abuse of opioids can lead to serious adverse outcomes such as overdose and

possibly death, which present an increasingly severe public health problem in the United States

(Wakeland et al., 2011). A great deal of the evidence demonstrates the need for increased

provider awareness in addition to increased vigilance with prescribing opioid pain medication to

address this epidemic. Provider education should focus on risk mitigation strategies including

the safe use of ER/LA opioid formulations, use of <100mg/day MED if possible, utilization of

risk assessment tools, adequate monitoring of patients’ opioid usage, recognition of high quality

opioid prescribing guidelines, and a co-prescription for naloxone to prevent opioid overdose

deaths. Several screening tools exist to assess for aberrant prescription drug-related behaviors

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 22

but only one tool assesses for the risk of overdose or the likelihood of OIRD. Nonetheless, use

of all available screening tools is encouraged because they can provide opportunity to expand the

patient-provider relationship and encourage open communication.

The aim of this project is to utilize the RIOSORD tool to identify individuals on COT

that are at increased risk of unintentional opioid overdose or serious OIRD and provide them

with a co-prescription of naloxone as a means to encourage safe opioid use and prevent overdose

deaths. The RIOSORD is the first tool intended to provide clinicians with the clinical decision

support to assess the risk of serious OIRD and determine the possible need for naloxone. This

tool provides a current, quantitative, evidence-based risk assessment that is able to determine

baseline risk status and provide on-going risk monitoring at future appointments. Review of the

literature clearly indicates that more rigorous, high quality studies are needed to provide

evidence-based practice recommendations in the care of patients on long-term opioid therapy.

Background and Significance

Historically, clinicians have used opioid pain medications to treat acute conditions such

as post-operative pain and pain related to trauma in addition to pain associated with cancer

and/or life-limiting illness (i.e., palliative care; Juurlink & Dhalla, 2012). However, in recent

decades, the United States has seen a dramatic increase in opioid prescribing for many chronic

pain conditions (Alford, 2016). Chronic pain is a significant problem for millions of Americans

and many may have disabling symptoms that interfere with day-to-day functions at home or in

the workplace (Juurlink & Dhalla, 2012). Recommended treatment for chronic pain incorporates

a multimodal approach with pain medication being only one part of the treatment plan.

However, access to recommended multidisciplinary services is sometimes limited by factors

such as cost, lack of insurance, non-coverage of services, lack of transportation, lack of services

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 23

in rural areas, and co-morbid health conditions that may limit treatment options such as surgery

(Juurlink & Dhalla, 2012). Due to such limitations, clinicians may initiate opioid pain

medication early in the management of chronic pain.

The use of long-term opioids to treat CNCP became common in the 1990s. The rise in

opioid use during this time coincided with the introduction of several new opioid formulations

such as OxyContin®, an extended-release oxycodone (without abuse deterrent properties) that

was introduced in 1995 within the United States (Juurlink & Dhalla, 2012). The American

Academy of Pain Management (AAPM) and the American Pain Society (APS) also endorsed

chronic opioid therapy during this time. Both the AAPM and the APS encouraged liberal use of

opioids to treat chronic pain based on research that indicated the development of addiction was

low when opioids were used for the relief of pain (Juurlink & Dhalla, 2012). In 2000, the Joint

Commission introduced new pain management standards, which emphasized that patients have

the right to pain relief (Manchikanti et al., 2012). The Joint Commission recommended regular

evaluation of pain in hospitalized patients as the “fifth vital sign” although pain is subjective and

not an objective measurement such as heart rate or temperature (Juurlink & Dhalla, 2012).

Support from national organizations along with the use of opioids in high doses and aggressive

pharmaceutical marketing has contributed to the prevalence of the opioid overdose epidemic.

Unfortunately, growth in the use of opioid pain medication to treat chronic pain has been

associated with increased misuse of prescription opioids and an increase in deaths due to

unintentional overdose (Alford, 2016).

Evidence indicates that patients on COT who are at risk of overdose are likely to benefit

from co-prescribing of naloxone. A study funded by the National Institutes of Health

demonstrated that naloxone can be successfully prescribed to a substantial proportion of patients

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 24

receiving COT and that naloxone co-prescribing was associated with reduced opioid-related

emergency room visits (Coffin et al., 2016). The RIOSORD provides clinicians with a validated

risk assessment tool with the ability to identify which patients may benefit from receiving a co-

prescription for naloxone. Fudin (2015) indicates that clinicians and even pharmacists can utilize

the RIOSORD tool to screen patients for risk of unintentional overdose or OIRD. Discussion of

the patient’s RIOSORD score provides an opportunity for a conversation about the possibility of

unintentional overdose and the benefits of risk-reduction strategies such as the co-prescribing

and use of naloxone. It is felt that use of the RIOSORD tool is a practical approach to screen for

risk of overdose in clinical practice and provide guidance on naloxone prescribing (Zedler, Xie,

et al., 2015; Fudin, 2015).

Conceptual Framework

The Stetler model of research utilization is the selected conceptual framework for this

project as it provides the structure and guidance needed to evaluate the literature, synthesize the

evidence, and initiate translation of information into practice. The Stetler model is an evidence-

based practice model that helps practitioners to incorporate evidence into daily practice and to

create formal change within an organization (National Collaborating Centre for Methods and

Tools, 2011). The model consists of five phases that serve as steps in identifying and utilizing

tasks to facilitate safe and effective evidence-based practice (Dang et al., 2015). Table 2 outlines

the phases involved in the Stetler model of research utilization and the specific tasks involved in

the application of each phase to this project.

The primary goal of this project is to utilize the RIOSORD score to guide naloxone

prescribing, which may reduce or prevent opioid-related deaths. The Stetler model of research

utilization is appropriate for this project because it is a practitioner-oriented model that utilizes

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 25

the critical thinking process to develop evidence-based practice changes. Implementation of the

RIOSORD tool to quantify a patient’s risk of overdose and increase access to naloxone

demonstrates effective use of evidence-based practice change by the clinician.

Needs Assessment

Drug overdose deaths in the United States hit record numbers in 2014 and at least half of

all opioid overdose deaths involved a prescription opioid (CDC, 2016c). Figure 2 demonstrates

the total number of U.S. overdose deaths involving opioid pain relievers from 2001 to 2014. The

total number of deaths increased by 3.4 times during that period (NIDA, 2015). Based on the

NIDA statistics, 78 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose and nearly half of a

million people died from opioid overdose from 2000 to 2014 (CDC, 2016c). The CDC (2016c)

acknowledges that overdoses from prescription opioid pain relievers are a driving factor in the

15-year increase in opioid overdose deaths. The most common opioids involved in overdose

Table 2

Project Application of the Stetler Model of Research Utilization

Phase Task

1. Preparation Identify problem, background and significance,

needs assessment, and outcome measures

2. Validation Review literature, synthesize evidence, and

assess tool validity

3. Comparative

Evaluation/Decision Making

Discuss findings, applicability and feasibility,

and additional information needed

4. Translation/Application Utilize evidence and implement change

5. Evaluation Measure outcomes, evaluate change

effectiveness, and disseminate findings

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 26

deaths are methadone, oxycodone, and hydrocodone (CDC, 2016b). Deaths from opioid

overdoses between 1999 and 2014 were highest among people aged 25 to 54 years of age; non-

Hispanic whites and American Indian or Alaskan Natives, compared to non-Hispanic blacks and

Hispanics; and men, but the mortality gap between men and women is closing (CDC, 2016b).

There were approximately 1.5 times more drug overdose deaths in the United States than deaths

from motor vehicle crashes in 2014 (CDC, 2016b).

The CDC analyzed data from the National Vital Statistics System multiple cause-of-death

mortality files for years 2013 and 2014 in order to track trends and shifting characteristics of

drug overdose deaths (Rudd et al., 2016). Results from this analysis noted significant increases

in drug overdose death rates in the Northeast, Midwest, and South census regions; the five states

with the highest rates of death were West Virginia, New Mexico, New Hampshire, Kentucky and

Ohio in 2014 (Rudd et al., 2016). Statistically significant increases in overdose death rate due to

Figure 2. Prescription opioid overdose deaths from 2001 to 2014. This chart illustrates

the number of overdose deaths from prescription opioids; the chart is overlayed with a

line graph to show number of deaths by females and males.

Source: CDC Wonder; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health;

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

02,0004,0006,0008,000

10,00012,00014,00016,00018,00020,000

Total Female Male

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 27

drug overdose were also noted in Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland,

Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania,

and Virginia (Rudd et al., 2016). Specifically, there was a 14.7% increase in overdose death rate

within the state of Virginia (Rudd et al., 2016). In Virginia, there was a total of 980 deaths with

an age adjusted rate of 11.7% in 2014 compared to 854 deaths with an age adjusted rate of 10.2%

in 2013 (Rudd et al., 2016). In 2013, Virginia’s Medicaid program spent $28 million on

members admitted to emergency departments and hospitals for treatment of substance use

disorder with $10 million of this spending occurring in Southwest Virginia (VCU School of

Medicine, 2016). Opioid prescriptions alone cost Medicaid $26 million annually (VCU School

of Medicine, 2016).

The total economic burden for opioid-related overdose, abuse, and dependence in the

United States is estimated to be $78.5 billion (Florence, Zhou, Luo, & Xu, 2016). Figure 3

provides an overview of the distribution of the economic burden of prescription opioid overdose,

abuse, and dependence. Over one-third of this amount ($28.9 billion) is due to increased health

care and substance abuse treatment costs and approximately one-quarter of the cost is borne by

the public sector in health care, substance abuse treatment, and criminal justice costs (Florence et

al., 2016). Fatal cases account for just over one quarter of the costs ($21.5 billion; Florence et

al., 2016).

Although many people benefit from prescription opioid pain medication to manage pain,

prescription opioids are often diverted for improper use (SAMHSA, 2016a). According to the

2013 and 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 50.5% of people who misused

prescription painkillers got them for free from a friend or relative compared to 22.1% who got

them from a prescriber (SAMHSA, 2016a). The CDC notes that individuals at highest risk of

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 28

overdose are about four times more likely than the average user to buy the drugs from a dealer or

other stranger (CDC, 2016a). Implementing safer opioid prescribing practices and utilizing the

CDC guideline may help to reduce the amount of prescription opioids available for nonmedical

use.

The clinical setting for the DNP project is Virginia Commonwealth University

Community Memorial Hospital (VCU-CMH) Pain Management Services, which is a pain

management office in a rural setting with one physician and one nurse practitioner. The practice

is a hospital-owned entity with affiliation to a larger health system that is located over 60 miles

away and it is the only pain management practice within the immediate area. Between the two

Figure 3. Distribution of the opioid economic burden. This pie chart depicts the distribution

of the economic burden from prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence.

Source: Florence, C. S.; Zhou, C.; Luo, F.; Xu, L. (2013). The economic burden of

prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States. Medical Care,

54(10), pp. 901-906, doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000625

Copyright © 2016 Medical Care. Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 29

providers, a mean of 264 established patients and 31 new patients are seen per month. The

physician sees all new patients for the first visit encounter. The patient population at VCU-CMH

Pain Management Services is 68% white, 38% African American, and 1% other race; 60% of the

patients are between 40 and 64 years of age and 60% are female. Forty-eight percent of the

population has Medicare insurance. This information is depicted in Figures 4 and 5.

Patients are seen at least every three months for routine follow-up, assessment, and

medication refills. The majority of patients are prescribed an opioid pain medication. According

to the CDC (2016a), an estimated 1 out of 5 patients with noncancer pain are prescribed opioids

in an office-based setting. Virginia is cited as prescribing opioid pain medications to 72-82.1 out

Figure 4. VCU-CMH Pain Management Services patient population. This chart

demonstrates the patient population by age and sex per month for 2016.

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept

18-39 yr 42 41 47 40 43 41 32 45 38

40-64 yr 194 210 205 223 223 251 197 220 208

>64 yr 94 107 92 103 117 112 94 117 102

Female 105 213 238 241 255 294 110 236 239

Male 226 146 109 124 128 110 213 142 109

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

Nu

mb

er

of

Pat

ien

ts

Patients per Month

2016 Patient Population by Age and Sex

18-39 yr 40-64 yr >64 yr Female Male

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 30

of 100 persons (CDC, 2016a). Nationally, the lowest concentration is 52-71 per 100 persons and

the highest 96-143 per 100 persons (CDC, 2016a). All of Virginia’s surrounding states are

among those with the highest prescribing rates including North Carolina, which is less than 20

miles away from VCU-CMH Pain Management Services.

National statistics indicate that most opioid overdose deaths occur in persons aged 25-54

years of age, non-Hispanic whites, and men. The majority of patients seen at VCU-CMH Pain

Management Services fit into at least two of these categories, although VCU-CMH sees fewer

patients 18-39 years of age than any other age group. Even though men are most likely to die of

an opioid overdose, women are more likely to use prescription opioids, which is demonstrated in

the clinic’s demographics noted above (CDC, 2016a). Data from the CDC (2016a) also indicates

that the economic burden of prescription opioid overdose (in addition to abuse and dependence)

Figure 5. VCU-CMH Pain Management Services patient population. This

pie chart demonstrates patient population by insurance for 2016.

48%

27%

17%

4%2% 2%

2016 Patient Population by Insurance

Medicare

Private

Medicaid

Worker's Compensation

Uninsured

CHAMPUS/VA

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 31

falls mostly onto the private sector (18%) and Medicaid populations (7%). Forty-four percent of

the patients at VCU-CMH Pain Management Services are insured by private (27%) and

Medicaid (17%) insurances.

Demographic similarities between VCU-CMH Pain Management Services patient

population and national/state statistics of persons affected by opioid-related overdoses and

clinician prescribing practices clearly indicate the need for risk mitigation strategies to reduce

opioid-related morbidity and mortality. Safer opioid prescribing includes taking measures to

protect patients with chronic pain who are medically dependent on opioid pain medication to

improve their functional status and quality of life. Such efforts include use of recommendations

from the CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, patient and provider education

on the correct use of opioid pain medication for chronic pain, and expanding access to and the

use of naloxone. Evaluating patients for risk of overdose will help to determine which patients

would most benefit from the availability of in-home naloxone.

Key Stakeholders

The increasing prevalence of opioid overdose, misuse, and abuse signifies the need for

change among medical societies and policymakers to help improve this public health burden.

Initiatives to reduce the opioid overdose epidemic can strengthen relationships among

stakeholders such as policymakers, clinicians, pharmacists, pharmaceutical companies, law

enforcement, first responders, health insurers, healthcare systems, communities, and families.

The Virginia General Assembly passed legislation in 2015 to expand access to naloxone so that

family members and other individuals can possess and use naloxone to reverse an opioid

overdose at home or in the community if needed (Levine et al., 2015). Additionally, the Virginia

Board of Pharmacy approved a protocol for the prescribing and dispensing of naloxone and the

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 32

Virginia Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services (DBHDS) Office of

Substance Abuse Services established REVIVE! as the Opioid Overdose and Naloxone

Education (ONE) program for the Commonwealth of Virginia. The REVIVE! ONE program

provides education on how to recognize and respond to an opioid overdose including

administration of naloxone. This training program is available to professionals, stakeholders,

and others with an interest in the opioid overdose epidemic.

In August 2016, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, the U.S. Surgeon General, initiated the

TurnTheTide campaign to raise awareness of the opioid overdose epidemic. Clinicians were

asked “to pledge their commitment to turn the tide on the opioid crisis” (Murthy, 2016, para. 5).

This pledge recommended that clinicians become educated in the treatment of pain, screen

patients for opioid use disorder and provide referral to evidence-based treatment if needed, and

to treat addiction as a chronic illness and not a moral failing (Murthy, 2016). Lastly, the CDC

developed a funded program called Prevention for States that provides specific state health

departments with resources to advance interventions for preventing prescription drug overdoses

(CDC, 2016e). Such resources include maximizing prescription drug monitoring programs,

community or insurer/health system interventions, state policy evaluations, and rapid response

projects. Clinicians and other healthcare professionals are encouraged to engage with local

agencies, law enforcement, community advocates, community service boards, and other

community partners to create local solutions to address opioid overdose and treatment at the

local and regional levels (Levine et al., 2015).

In accordance with national calls to improve opioid prescribing practices and reduce the

risk of opioid-related deaths, the intended audiences for this project are patients on COT and

prescribers of opioids. The key stakeholders involved are the patients in addition to their

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 33

families and communities, the prescribers and clinical staff, and management of the clinical

setting, which includes the office manager, the vice-president of physician services, and the chief

executive officers from both the local hospital (CMH) and its affiliate partnership (VCU Health

System). Decisions within the office are made through collaboration between the two providers,

office manager, and the vice-president of physician services with approval from the local

hospital’s chief executive officer as needed.

Barriers and Facilitators

A major potential barrier to the project includes limited time during appointments to

screen for risk of overdose or OIRD. This barrier may affect whether the screening is performed,

as well as the ability to provide adequate patient education on risk of overdose and use of

naloxone to prevent overdose deaths. Lack of prescription drug coverage and the high cost of

certain naloxone delivery systems may limit patient access to naloxone. Some insurances require

a prior authorization for certain naloxone delivery systems, which is time consuming for both the

office staff and clinicians. A majority of insurances provides coverage for generic naloxone

administered intranasally via a syringe and atomizer, but this delivery method is cumbersome

and more difficult to administer than commercially available pre-prepared, ready-to-use delivery

systems (e.g., the Evzio® Auto-Injector and Narcan® Nasal Spray). Possible strategies to

overcome these barriers include utilizing patient assistance programs from the pharmaceutical

company or developing a pre-authorization letter template that is tailored to the patient’s needs.

These strategies may hasten the prior authorization process and thus reduce patient wait time for

this life-saving medication.

The office staff and clinicians at VCU-CMH Pain Management are dedicated to quality

care and patient safety in the treatment of chronic pain conditions. The staff demonstrates

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 34

effective teamwork and is knowledgeable of the patient population and their needs, which are

important attributes when incorporating change within an established system. Other strengths

that will facilitate project implementation include use of written opioid agreements with all

patients on COT, use of an electronic medical record (EMR) with the ability to track prescribing

practices, and use of referral guidelines to ensure the appropriateness of patients referred to the

office for chronic pain treatment.

Benchmarks

In March of 2015, Health and Human Services Secretary Burwell introduced the Opioid

Initiative to address opioid-related morbidity and mortality in the United States (U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services [HHS], n.d.). The initiative targets the following three focus

areas: 1) reforming prescribing practices to reduce excess opioid prescribing; 2) improving

naloxone development, distribution, and access; and 3) expanding access to medication-assisted

treatment (HHS, n.d.). Selected metrics to measure progress toward the agency priority goal of

reducing opioid-related morbidity and mortality include:

a decrease in the total morphine milligram equivalents dispensed in the U.S. outpatient

retail pharmacy setting by 10%;

an increase in the number of prescriptions dispensed for naloxone in the U.S. outpatient

retail pharmacy setting by 15%; and

an increase in the number of unique patients receiving prescriptions for buprenorphine

and naltrexone in the U.S. outpatient retail pharmacy setting by 10% (HHS, n.d.).

No other quality measures or benchmarks exist on opioid overdose deaths in patients on

COT or the practice of co-prescribing naloxone among clinicians. The Drug Policy Alliance

(2016) notes that the nation needs new metrics in which to measure the success of our nation's

drug policies and that the primary measure of effectiveness should be a reduction in opioid-

related harm such as overdose deaths versus measuring for slight fluctuations in drug use. A

scientific analysis performed by NIDA found a 1,170% increase in prescriptions of naloxone

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 35

dispensed from retail pharmacies in the U.S. between the fourth quarter of 2013 and the second

quarter of 2015 (NIDA, 2016). Many organizations such as SAMHSA, CDC, NIDA, World

Health Organization, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommend expanding

of the use of naloxone as an effective strategy to reduce opioid-related deaths. An appropriate

goal to gauge the success of this DNP project would be a 15% increase in the number of

prescriptions written for naloxone by clinicians at VCU-CMH Pain Management as noted in the

aforementioned agency priority goal. Although another important measure would be a reduction

in the total morphine milligram equivalents prescribed, that metric is not within the scope of this

project.

Budget

In terms of economic analysis, the cost-consequence analysis method pertains to this

project because it allows for comparison between costs and health-related outcomes so that

stakeholders can form their own opinions regarding the best treatment option. The outcome is to

prevent opioid-related deaths by utilizing the RIOSORD score to guide naloxone prescribing;

ultimately, the pertinent health outcomes of consideration are that of life or death for patients’

receiving COT. Use of naloxone in an opioid-related emergency is a life-saving measure that is

effective in preventing death or other possible detrimental effects. However, lack of naloxone

availability contributes to negative outcomes that lead to consequential expenses such as

hospitalization or funeral expenses. These consequential expenses result in increased costs to

third party payers such as insurance companies or the family. Except for the cost of a medication

that goes unused, there are no negative consequences associated with prescribing naloxone to a

high-risk patient who never has an opioid-related emergency. However, one must consider cost

to the patient or insurance company for obtaining the medication in comparison to costs of a

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 36

negative outcome. Table 3 provides a summary of benefits of this DNP project to both the

patient and the institution.

A cost analysis was performed to evaluate the potential cost and sustainment of outcomes

of this DNP project. The major expense associated with the project is for materials and supplies,

which will be used to make copies of the RIOSORD questionnaire and patient education

handouts on signs of overdose and naloxone administration. An electronic version of the

RIOSORD tool, referred to as Naloxotel, will be utilized to screen patients for risk of overdose.

Use of Naloxotel will be provided free of charge by Dr. Jeffrey Fudin from Remitigate, LLC.

However, copies of the completed questionnaires will be required to facilitate data collection and

entry, and a copy will be provided to the patient if desired. Educational videos on naloxone

administration are available at no cost via the PrescribetoPrevent.org and www.narcan.com

websites. Total direct costs of the project are $155.97. The indirect costs are expenses that are

already associated with the established practice setting and thus will not add to costs of project

Table 3

Benefits of DNP Project to Patients and Institution

Benefits to Patient Benefits to Institution

Provision of a life-saving medication if

needed

Adherence to opioid prescribing

recommendations

Opportunity to receive education on

contributing factors for increased risk of

overdose or serious OIRD

Implementation of a decision support tool to

quantify risk for overdose or serious OIRD

Increased access to naloxone Utilization of forward thinking risk

mitigation strategies

Quality care with improved outcomes and

increased safety for those on COT

Patient safety, improved outcomes, and

quality care for patients requiring COT

Notes. COT = chronic opioid therapy; OIRD = opioid-induced respiratory depression.

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 37

implementation. These costs include that for the two providers that will screen patients for

overdose as well as additional office staff (i.e., two nurses and one clerical worker), facilities,

and the EMR with electronic prescribing capability. Total indirect costs are $61,938.00 for a six-

month period. Provider and nurse salary is based on a total of 120 hours per staff member for the

six months; this allows for ten minutes per patient (five minutes for the clerical worker) with a

projected total of 1,440 patients screened (i.e., 720 patients per provider/nurse). A detailed

budget for the DNP project is presented in Appendix D. The minimal direct costs associated

with this DNP project should not hinder future sustainment of its efforts. Once patients receive

their initial overdose or serious OIRD screening, it can be repeated annually or as needed to

update the individual’s risk index and reinforce overdose education and prevention efforts.

Annual use will also provide an opportunity to renew the naloxone prescription if out of date.

Project Description

This DNP quality improvement project examines the associations between COT, the

opioid overdose epidemic, and the possibility of serious OIRD in patients receiving COT.

Inappropriate opioid pain medication use in addition to prescribing high doses of opioids (i.e.,

>100mg MED) are contributory to the increased morbidity and mortality in patients on COT

secondary to the possibility of serious OIRD. This project strives to promote quality care to

those suffering with CNCP while encouraging safe opioid prescribing and safe opioid use. The

DNP project team consists of the DNP student who will lead as the project investigator; a clinical

advisor assigned by the school of nursing, and two content experts who were selected by the

DNP student. The first content expert is an anesthesiologist who is board certified in pain

management and the second content expert is a doctor of pharmacy at a local retail pharmacy.

The Stetler model of research utilization is the selected conceptual framework to provide

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 38

structure and guidance for the translation of evidence-based research into practice change for this

DNP project. Appendix E provides a schematic of the Stetler model. In addition to aligning

well with national calls for safer opioid prescribing, this DNP project enhances the current state

of practice at VCU-CMH Pain Management Services through increased awareness for overdose

risk screening and the existence of a validated risk assessment tool.

Mission Statement

The mission of this project is to provide effective pain management treatment to those

with various chronic pain conditions in compliance with current pain management guidelines

while concentrating on patient safety and quality outcomes through the provision of naloxone to

those determined to be at an increased risk of serious OIRD. The project mission is reflective of

the organizational mission, which is to provide excellence in the delivery of healthcare (VCU

Health CMH, 2016). Organizational quality improvement strategic plans that correlate to the

DNP project include a focus on quality and excellence, creating patient-focused systems, and

meeting growth demands of the outpatient population. Such strategic plans help to unify future

directions and purposes of VCU-CMH with its medical staff while considering the community’s

needs and prioritization of areas for improvement. The organization’s vision is to be a national

leader in healthcare through continuous improvement while recognizing the following values:

integrity at all levels; compassion and service towards others; teamwork that revolves around

respectful and collegial relationships among physicians, employees, patients, and volunteers;

ethical behavior; excellence in our processes and outcomes; and professionalism (VCU Health

CMH, 2016).

Goals and Objectives

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 39

The DNP student, as the project investigator, defines the scope of this project in two

primary goals directed at the project intervention/clinicians (goal #1) and the patient population

(goal #2). Table 4 summarizes the primary goals and corresponding objectives.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures include the calculated RIOSORD score for each patient

assessed, the number of high-risk patients, and the number of naloxone prescriptions provided.

Secondary outcome measures include an analysis of the individual covariates from the IMS

Table 4

DNP Project Goals and Objectives

Goal #1 Goal #2

Reduce or prevent opioid-related overdoses

over the six-month project period.

Demonstrate safe opioid use as evidenced

by lack of a serious OIRD event or proper

treatment of a serious OIRD event over

the six-month project period.

Objectives: Objectives:

1. Familiarize clinicians with factors

associated with increased risk of overdose

and/or serious OIRD in patients on COT.

2. Provide information on development of

the RIOSORD tool including differences

in the VHA and IMS populations.

3. Implement use of the IMS RIOSORD tool

in clinical practice to assess risk of

overdose or serious OIRD.

4. Utilize the RIOSORD risk index score to

guide naloxone co-prescribing in patients

on COT found to be at increased risk of

overdose or serious OIRD.

1. Educate patients on factors associated

with increased risk of overdose or

serious OIRD.

2. Provide patient’s with individualized

risk of overdose or serious OIRD

based on RIOSORD score.

3. Provide a co-prescription of naloxone

to use in an opioid-related emergency

if needed.

4. Educate patient and family/friends on

the signs and treatment of opioid

overdose including the proper use of

naloxone.

Note. COT = chronic opioid therapy; IMS = commercial insurance; OIRD = opioid-induced

respiratory depression; RIOSORD = Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-Induced

Respiratory Depression; VHA = Veteran’s Health Administration.

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 40

RIOSORD tool itself (e.g., certain co-morbid health conditions over the past six months and

current medication consumption). Table 5 provides an outline of these covariates.

Table 6 provides a description of how the project goals and objectives link to the primary

and secondary outcome measures. Other secondary long-term outcomes of interest include

whether an overdose or serious OIRD event occurred; if so, did the patient have naloxone

available to use, was naloxone used, and results of the serious OIRD event. However, data for

such long-term outcomes will not be collected as a longitudinal study for longer than six months

would be necessary to obtain this data.

Table 5

Covariates Analyzed in the IMS RIOSORD Tool

Co-morbid Health Conditions Current Medication Consumption

Substance use disorder

Bipolar disorder or schizophrenia

Stroke or other cerebrovascular disease

Chronic kidney disease (with clinically

significant renal impairment)

Heart failure

Non-malignant pancreatic disease

Chronic pulmonary disease

Chronic headache

Fentanyl (transdermal or transmucosal)

Morphine

Methadone

Hydromorphone

ER/LA opioid formulation (including

any of the above named opioids)

Concomitant benzodiazepine use

Concomitant anti-depressant use

Current opioid dose >100mg MED

(includes all prescription opioids

consumed on a daily basis)

Note. ER/LA = extended-release/long-acting; IMS = commercial insurance; MED =

morphine equivalent dose.

Adapted from: Zedler, B., Saunders, W., Joyce, A., Vick, C., & Murrelle, L. (2015).

Validation of a screening risk index for overdose or serious prescription opioid-induced

respiratory depression. Poster session presented at the 2015 American Academy of Pain

Medicine Annual Meeting, National Harbor, MD.

IMPLEMENTING A RISK INDEX TOOL 41

Table 6

Aligning Goals and Objectives with Outcome Measures

Goals/Objectives Outcome Measures

Goal #1: Reduce or prevent opioid-related

overdoses over the six-month project period.

Objectives: Primary Outcomes:

1. Familiarize clinicians with factors associated