Rosen - The Classical Style

Transcript of Rosen - The Classical Style

The Classical Style

By CHARLES ROSENThe Classical Style Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven Arnold Schoenberg Sonata Forms The Musical Languages of Elliott Carter Plaisir de louer, plaisir de penser Conversation avec Catherine Temerson The Frontiers of Meaning Three Informal Lectures on Music The Romantic Generation

By CHARLES ROSEN

AND HENRI ZERNER

Romanticism and Realism The Mythology of Nineteenth-Century Art

Copyright 1997, 1972, 1971 by Charles Rosen All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First published as a Norton papetback 1998 The text of this book is composed in 10/11.5 Times ~oman with the display set in Times Roman Composition' by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Manufacturing by Courier CompaniesLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosen, Charles, 1927The classical style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven / Charles Rosen.Expanded ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-393-04020-8 1. Classicism in music. 2. Haydn, Joseph, 1732-1809-Criticism and interpretation. 3. Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus, 1756-1791Criticism and interpretation. 4. Beethoven, Ludwig van, 1770-1827Criticism and interpretation. 5. Music-18th century-History and criticism. I. Title. ML195.R68 1997 780' .9'03~c20 96-27335 CIP

ISBN 0-393-31712-9 pbkW. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 www.wwnorton.com W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 15116 Wells Street; London WIT 3QT

7 890

The Classical StyleHaydn, Mozart, Beethoven

EXPANDED EDITION

New YOrK Lonaon

For Helen and Elliott Carter

Zangler: Was hat Er denn immer mit dem dummen Wort 'klassisch'? Melchior: Ah, das Wort is nit dumm, es wird nur oft dumm angewend't. Nestroy, Einen lux will er sich machen

[Zangler: Why do you keep repeating that idiotic word "classic"? Melchior: Oh, thg word isn't idiotic, it's just oftgll usd idiotically.]

ContentsPreface to the First Edition A New Preface Acknowledgments Bibliographical Note Note on the Music ExamplesI INTRODUCTION

xi xiii xxvii xxix xxxi19

1. THE MUSICAL LANGUAGE OF THE LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURYPeriod style and group style, 20; Tonality, 23; Tonic-dominant polarity, 25; Modulation, 26; Equal temperament, 27; Weakening of linear form, 28.

2. THEORIES OF FORMNineteenth-century conception of sonata form, 30; Twentieth-century revisions, 32 ; Schenker, 33; Motivic analysis, 36; Vulgar errors, 40.

30

3. THE ORIGINS OF THE STYLEDramatic character of the classical style, 43; Range of styles 1755-1775, 44; Public and private music, 45; Mannerist period, 47; Proto-classical symmetries and patterns, 49; Determinants of form, 5 I.

43

II

THE CLASSICAL STYLE

1. THE COHERENCE OF THE MUSICAL LANGUAGE 57 Periodic phrase, 57; Symmetry and rhythmic transition, 58; Homogeneous (Baroque) vs. heterogeneous (classical) rhythmic systems, 60; Dynamics and ornamentation, 62; Rhythmic and dynamic transition (Haydn Quartet 0p. 33 no. 3),64; Harmonic transition (modulation), 68; Decorative vs. dramatic styles, 70; Conventional material, 71; Tonal stability and resolution, 72; Recapitulation and articulation of tension, 74; Reinterpretation and secondary tonalities, 78; Subdominants, 79; Contrast of themes, 80; Reconciliation of contrasts, symmetrical resolution, 82; Relation of large form to phrase, expansion technique (Haydn Piano Trio, H.I9, 83); Correspondence of note, chord, and modulation, 89; Articulation of rhythm, weight of individual beat, 90; Sonata style and eccentric material: fantasy form (Mozart, Fantasy K. 475), 91; Audible vs. inaudible form, 93; Extra-musical influence, 94; Wit in music, 95.

2. STRUCTURE AND ORNAMENTSonata forms generalized, 99; Structure vs. ornament, 100; Ornamentation in the late eighteenth century, 101; Radical change in function of decoration, 107

99

III

HAYDN FROM

1770 TO THE DEATH OF MOZART

1. STRING QUARTETHaydn and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, I I I; Beginning in a false key, 112; Innovations of the Scherzi quartets, thematic accompaniment, 115; Energy latent in musical material, 120; Dissonance as principal source of energy, 120; DIrectional power of material, 129; Sequence as source of energy, 134; Reinterpretation by transposition, 135; Relation of string quartet to classical tonal system, 137; Further development of Haydn'S string quartets, 138; String quartet and the art of conversation, 14 T.

111

Contents2 .. SYMPHONYDevelopment of the orchestra and symphonic" style, 143; stylistic progress, 146; Sturm und Drang style, 147; Symphony no. 46, 147; Weakness of rhythmic organization of early Haydn, 149; Symphony no. 47, 151; Influence of opera, 153; Symphony no. 75, 155; New clarity and sobriety, 157; Symphony no. 81, 157; Wit and symphonic grandeur, 159; Oxford Symphony, 159; Haydn and pastoral, 162.

143

IV

SERIOUS OPERA

164

Problematic status of opera seria, 166; Conventions of opera seria and buffa, 167; Eighte~nth-century tragedy, 168; High Baroque style, 169; Dramatic and elegiac modes, 170; Gluck, 170; Neo-classical doctrine, 171; Music and the aesthetic of expression, 173; Words and music, 173; Gluck and rhythm, 174; Mozart and Idomeneo, 177; Recitative and complex forms, 178; Fusion of seria and buffa, Marriage 0/ Figaro, I8,I.; Fidelio, 183.

V

MOZART

1.

THE CONCERTO

185

Mozart and dramatic form, 185; Tonal stability, 186; Symmetry and the flow of time, 187; Continuo playing in the late eighteenth century, 191; Musical significance of the continuo, 194; Concerto as drama, 196; Opening ritornello, 197; Concerto in E flat K.27 I, 198; Piano exposition as dramatization of orchestral exposition, 205; Symmetry of climax, 207; Secondary development within recapitulation, 2 II; Slow movement of K.27 I as expansion of opening phrase, 2 II; Mirror symmetry, 2 12; Concerto finale, 213; Sinfonia Concertante K. 364, 214; Thematic relationships, 215; K.4 12, K4I3, K.4i5, 218; K-449, 219; K-456, modulating second theme, 22 I; Dramatic range of slow movement, 223; Variation-finales, 225; K. 459 and fugal finales, 226; K. 466, art of rhythmic acceleration, 227; Thematic unity, 233; K. 467 and symphonic style, 235; Slaw movement, improvisation, and symmetry, 238; K. 482, orchestral color, 240; K.488, articulation of close of exposition, 24 I; Slow movement and melodic structure, 243; K.503, technique of repetition, 251; Major and minor, 254; Sense of mass, 256; K. 537, proto-Romantic style and loose melodic structure, 258; Clarinet Concerto, continuity of overlapping phrases, 260; K. 595, resolution of chromatic dissonance, 263.

2.

STRING QUINTET

264

Concertante style, 264; K 174, expanded sonority and expanded form, 265; K.515, irregular proportions, 267; Expansion of form, 273; K.5I6, problem of classical finale, 274; Major ending to a work in the minor, 276; Expressive limits of the style, 277; Place of minuet in the order of movements, 280; Virtuosity and chamber music, 281; K 593, 281; Slow introductions, 282; Harmonic structure and sequences, 283; K. 614, influence of Haydn, 286.

3. COMIC OPERAMusic and spoken dialogue, 288; Classical style and action, 289; Ensembles. sextet from The Marriage of Figaro and sonata form. 290; Sextet from Don Giovanni and sonata proportions, 296; Tonal relations in opera, 2 98; Recapitulation and dramatic e~igency, 30 I; Operatic finales, 302; Arias, 306; 'Se vuol ballare' from The Marriage of Figaro, 308; Coincidence of musical and dramatic events: graveyard scene from Don Giovanni, 309; Comedy of intrigue, 312; Eighteenth-century concept of personality, 3 13; Comedy of experimental psychology and Marivaux, COSl

288

viii

Contentsfan tutte, 314; Virtuosity of tone, 316; Die Zauber{lote, Carlo Gozzi and the dramatic fable, 317; Music and moral truth, 319; Don Giovanni and the mixed genre, 321; Scandal and politics, 322; Mozart as subversive, 3 2 4.

VI

HAYDN AFTER THE DEATH OF MOZART329

1. THE POPULAR STYLEHaydn and folk music, 329; Fusion of high art and popular style, 332; Integration of popular elements, 333; Surprise return of theme in finales, 337; Minuets and popular style, 340; Orchestration, 342; Introduction as dramatic gesture, 345.

2.

PIANO TRIO

351

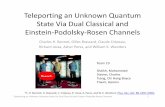

Reactionary form, 351; Chamber music and pianistic virtuosity, 352; Instruments in Haydn's day, 353; Doubling of bass line by cello, 354; H.I4, 355; H.22 and expansion of the phrase, 356; H.28, Haydn's early style transformed, 359; H.26, acceleration of motivic elements within a phrase, 361; H.3 I, luxuriant variation technique, 362; H.30, Haydn's chromaticism, 36 3.

3.

CHURCH MUSIC

366

Expressive vs. celebrative aesthetic, 366; Opera bufJa style and religious music, 367; Mozart's parodies of Baroque style, 367; Haydn and religious music, 368; Oratorios and pastoral style, 370; 'Chaos' and sonata form, 370; Beethoven's Mass in C Major, problems of pacing, 373; n Major Mass, 375.

VII1. BEETHOVEN

BEETHOVEN379

Beethoven and post-classical style, 381; Beethoven and the Romantics, 381; Substitutes for dominant-tonic relationship, 382; harmonic innovations of the Romantics, 383; Beethoven and his contemporaries, 386; G Major Piano Concerto, creation of tension by tonic chord, 387; Return to classical principles, 389; Eroica, proportions, codas, and repeats, 392; Waldstein, unity of texture and theme, 396; Appassionata and unity of work, 399; Romantic experiments in Beethoven C Minor Variations, 400; Program music, 40 I, A 11 die feme Geliebte, 402, Years 18 I 3 18 17, 403; Hammerklavier, inti~ate relation between large form and material, 464; Role of deseending thirds in eonstruetion of sequenee, 407; Be quential structure of development of the Hammerklavier, 409; Relation to large key sequenee, 413; Relation to thematiG strueture, 415; ."..1 '18. A~, 420; Metronome and tempo, 421; Change in style since Op.22, 422; Scherzo, 423; Slow movement, 424; Introduction to finale, 427; Fugue, 429; Place of HammerklaPier in Beethoven's work, 434; Transformation of variation form into classical form, 440; Op I I I, 441; Beethoven and the weight of musical proportions, 445.

2. BEETHOVEN'S LATER YEARS AND THE CONVENTIONS OF HIS CHILDHOODBeethoven ' s ongmabty and the style of the InOS, 449; The cadential trill 10 op. I II, 449; The traditional final trill in concerto cadenzas, 450; The suspended afterbeat: Sonata op. 101, 457; Conventional concerto figuration transferred to plano sonata; 458; Two stereotypes of the 177os: Subdominant in the recapitulation, relative minor 10 the development, 460; Subdorrunant transferred to coda, 463; Convention and 10novation: Relative minor in Mozart's K. 575 and Coronation Concerto, 467; Haydn's

449

ix

Contentsconsistent use of the stereotype, 471; Beethoven's naked display of the convention, 474; Stereotype and inspiration in op. 106, 484; The two conventions in op. 110, 488; Integration and motivic alternation in op. 110, 494; Integration of tempi, 499; Espressivo and rubato, 499; Radical key relations and dramatic sttucture, 50 I; Dramatization of the academic elements of fugue, 502; Unity of tempo and the rhythmic notation of the finale, 506; Beethoven's amiability, 507; Pushing back the limits of contemporary style, 508; Synthesis of 18th-century conventions of the variation set, 509; Late Beethoven, 18th-century sociability, and the language of music,

5 10EPILOGUE

513

Schumann's monument to Beethoven (C Major Fantasy), 45 I; Return to Baroque, 453; Change in tonal language, 453; Schubert, 454; His relation to classical style, 455; Use of middle-period Beethoven as model, 456; Classical principles in late Schubert, 459; Classical style as archaism, 4 60.

INDEX OF NAMES AND WORKS

523

Preface to the First Edition

I have not attempted a survey of the music of the classical period, but a description of its language. In music, as in painting and architecture, the principles of 'classical' art were codified (or, if you like, classicized) when the impulse which created it was already dead: I have tried to restore a sense of the freedom and the vitality of the style. I have restricted myself to the three major figures of the time as I hold to the old-fashioned position that it is in terms of their achievements that the musical vernacular can best be defined. It is possible to distinguish between the English language around 1770 and the literary style of, say, Dr. Johnson, but it is more difficult to draw a line between the musical language of the late eighteenth century and the style of Haydn-it is even doubtful whether it would be worth the trouble to try to do so. There is a belief, which I do not share, that the greatest artists make their effect only when seen against a background of the mediocrity that surrounded them: in other words, the dramatic qualities of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven are due to their violation of the patterns to which the public was conditioned by their contemporaries. If this were true, the dramatic surprises in Haydn, for example, should become less effective as we grow familiar with them. But any music-lover has found exactly the contrary. Haydn's jokes are wittier each time they are played. We can, of course, grow so familiar with a work that we can no longer bear to listen to it. Nevertheless, to choose only the most banal examples, the opening movement of the Eroica Symphony will always seem immense, the trumpet call of Leonore lVo. III will always be a shock to anyone who listens once again to these works. This is because our expectations do not come from outside the work but are implicit in it: a work of music sets its own terms. How these terms are set, how the context in which the drama is to be played out is created for each work, is the main subject of this book. I am concerned, therefore, not only with the meaning or the significance of the music (always so difficult to put into words) but also with what made it possible to possess and to convey that significance. In order to give some Idea of the scope and varIety of the perIod I have foJlowed the development of different genres for each composer. The concerto, the string quintet, and comic opera were obvious choices for Mozart, as were the symphony and the string quartet for Haydn. A discussion of Haydn's piano trios will convey the idiosyncratic nature of the chamber music with piano of that time. Opera seria demanded separate treatment, and Haydn's oratOIios and masses pIovided an occasion to discuss the general xi

Preface to the First Editionquestion of Church music. The relation of Beethoven to Mozart and Haydn clearly need~d to be defined by a more general essay, but the major part of the examples could be drawn easily from the piano sonatas. By such subtp,rfuge I have hoped to represent all the important aspects of the classical style. There is a glaring inconsistency in the pages that follow: 'classical' has always a sman 'c,' while 'Baroque,' 'Romantic,' etc., are proclaimed by their initial capitals. The reason for this is partly aesthetic: I have had to use the wor ,

r-r1

.. . .. .

I .. . .

.~

.

.. .,..

CP

.-

..----:--

..-r

~

~

--...-

'-... -_:Z.I

..1-.

'It.

I

..

~ ~

I

.,

...

."19-

. .

~....I

I

.

is changed into:

362

Piano Trio87II

~ln.

-.Cello

--

+9--

...---

~

-- --

-+-==t.:f'"::: ---

.--------::-----#:1_--f'L.:f:

P

r"'i1+(j

p" 1

~ .,