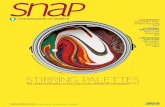

ROMANTICISM Stirring a sleeping beauty

Transcript of ROMANTICISM Stirring a sleeping beauty

24 LIFE&STYLE THE SATURDAY AGE • OCTOBER 15, 2011

ART & DESIGNR O M A N T I C I S M

Stirringa sleepingbeauty

G A B R I E L L A C O S L O V I C H

WITH its taint of superficiality andtriteness, beauty has been unfash-ionable in the art world — unlesstempered by a heavy dose of ironyand self-knowing. The "concept"has been king and brave are theartists who have favoured beautyand aesthetics over a more theore-tical approach.

But a new book on contemporaryAustralian art reclaims a space forbeauty—specifically romanticism.Simon Gregg, the dynamic curatorof the Gippsland Art Gallery, makesa bold assertion in his debut book,New Romantics: Darkness and Lightin Australian Art, arguing thatromanticism, an ideal that orig-inated in the late 18th century as areaction against the rationalismand order of the Enlightenment,has been flourishing in Australia

I during the past 10 years. Character-; ised by art works that were unapo-; logetically beautiful, romanticism; valued emotion and intuition overi reasoning and intellect. It was typi-• fled by artists such as Germani painter Caspar David Friedrich andi England's Joseph Turner, masters ofi the brooding, vaporous landscape.

But it fell out of favour in thei cool, irony-laden, post-modern era: — unaided by the fact that romanti-1 cism was readily confused with thati prosaic adjective "romantic", refer-i ring to all things saccharine andi sentimental, to Hallmark cards and• candle-lit dinners.

Romanticism, on the otheri hand, was anything but senti-I mental — it could be surreal andi sinister too, as anyone familiar withi the paintings of those otheri romantic greats, Francisco de Goya

i and Eugene Delacroix, would know."For much of the 20th century, art-

i ists were afraid to make art that wasI beautiful... and it's come back in ai big way and quite instinctively, not\" Gregg says.

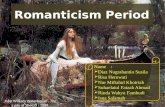

He sees the echoes of romanti-I cism in the stylistically diversei works of many contemporaryi Australian artists, 36 of whom hei has surveyed in his book. He sees iti in the febrile night scenes and| moody skies of photographer Billi Henson. In the surreal landscapesi of Louise Hearman, painter of

bizarre, supernatural compositionswith disembodied heads, spookychildren, grotesque animals andghostly figures. He sees it in thegothic photographs of Jane Burton,her images of dark, decrepit housesand sensual, suggestive nudes, sil-houetted against gauzy drapes. Andin the atmospheric, etherealcanvases of Chris Langlois, WilliamBreen and Greg Wood, which evokethe play of light, cloud and fog.

He even sees it in the cementcasts of everyday objects by SusanMilne — whose sculptures of toast-

ers, food processors and portableTVs he describes as "future ruins"or "fossilised totems".

"What all these artists bring totheir work is... a search for truthand beauty," he says.

The romantic search for mean-ing ranged into the mystic and spir-itual, communicated throughpaintings of the natural environ-ment. A contemporary example isMelbourne artist Kathryn Ryan,known for her meditative andunashamedly beautiful paintings oftrees. Ryan grew up on a dairy farm

IOCTOBER 15, 2011 • THE SATURDAY AGE LIFE&STYLE 25

near Warrnambool, one of 10 child-ren in a Catholic family. For her, theland has always been imbued witha strong sense of spirituality, whichshe reflects in her paintings.

No longer a practising Catholic,art has become her substitute forreligion, fulfilling her need for"ritual, substance, consistency".

Some of the artists featured inGregg's book, however, were reluct-ant to be labelled "romantic", notwanting their work to be reduced toone idea. In some ways, their resist-ance is true to the romantic spirit,

I

which favoured the primacy of theindividual. Romantics were lonewolves rather than pack animals.

Among those who embraced theterm "romantic" is Melbournepainter Tony Lloyd, whose workEternity, graces the cover of Gregg'sbook. Lloyd believes that a renewedattention on beauty and romanti-cism is overdue.

"You have not been allowed totalk about art in terms of theromantic for the last 20 years, cer-tainly not in academic circles,"Lloyd says. "You certainly weren't

From left, Deep in the Woods by Tony Lloyd, Untitled by Louise Hearman and Panmure Cypress by Kathryn Ryanbring emotion and intuition into the artistic framework. They are among the works featured in New Romantics:Darkness and Light in Australian Art.

allowed to talk about the beauty ofart, that was my experience at uni-versity, and I think what was lost inthat academic dismissal of theromantic is that people forgot howto talk about beauty in art.

"In most of the discourses onart, it seemed that beauty couldonly be used in an ironic andknowingly post-modern way...that didn't stop me from wanting topaint the sort of paintings that Iwanted to make but I did wish thatthere was more writing about thesort of art that I was making."

Lloyd's oil paintings, with theirslick surfaces and blurred edges,are dangerously alluring. His darkhighways, bordered by shadows oftowering trees, and his menacingmountain peaks draw you in — youwant to drive down that highway,climb those mountains, despite, oreven because of, the risk. Lloyd andGregg were in the same year at uni-versity, both studying painting.

"Artists wereafraid to makeart that wasbeautiful."

But while Lloyd persisted, uni-versity killed Gregg's desire to paint.

"My own art practice was neverremotely romantic," he says. "Per-haps because romanticism wassuch a huge thing for me, I was tooafraid to make art about it, perhapsalso because I knew it wasn't 'cool'and I was worried what peoplewould think. So it's given me anenormous amount of respect andadmiration for the artists in thebook, because they've had the cour-age to be brave and individual intheir art where I was not."

New Romantics is a vindication

of Gregg's stifled impulses. He isnow championing the work of art-ists who persevered with their takeon beauty. Five years in the making,Gregg's book was self-funded. Hav-ing spent about $6000 for the rightsto publish historical images, he'snot expecting to make a profit fromsales. But he was never motivatedby money. He was driven, rather, bythe desire to bring these artists tothe attention of a broader public.

"This is a book I've wanted topick up and buy for years and years,but it simply didn't exist. I had to goout and make it myself," Gregg says.

»New Romantics: Darkness and Light inAustralian Art is published by AustralianScholarly Publishing. An exhibition based onthe book will open at the Gippsland ArtGallery, in Sale, on November 19.

Chris Langlois's latest exhibition, AnotherPlace, is at Gould Galleries, 270 ToorakRoad, South Yarra, until November 12.