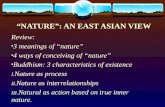

Romantic View of Nature

description

Transcript of Romantic View of Nature

Romantic View of Nature

Romantic Encounters with Nature Personification of Nature Identification with Personified Nature Elevation of Persona’s Spirit—Rebirth:

feelings of youth Perception of the Spiritual in Nature Expansion of Persona’s Vision to a Larger

Humanity

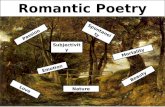

Poetry: Romantic Theories

Wordsworth: “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings”; “from emotion recollected in tranquillity”

Shelley: Poets “the unacknowledged legislators of the world”

Keats: “truth of Imagination”; “Beauty is truth, truth beauty”

American Romantics: Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman More direct connection with Nature:

Emerson: “transparent eyeball”; “Nature is the incarnation of thought”

Thoreau: “Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?”

Whitman: “My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air”

Identification without personification

Romanticism and Landscape

Pastoral, Picturesque, Sublime

Poussin, Arcadian Shepherds (1638-39)

Stowe: Temple of Ancient Virtue

English Landscape Tradition

Edmund Burke, Philosophical Inquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757-59)

William Gilpin, Three Essays on Picturesque Beauty (1794)

Uvedale Price, Essay on the Picturesque (1794)

Edmund Burke The Sublime

gives people harsh and antisocial feelings of “agreeable horror”

associated with things or experiences that are powerful, threatening, vast or unclear

generally associated with masculine qualities associated with representations rather than

direct experience

Edmund Burke

The Beautiful the beautiful gives people harmonious and

sociable feelings. associated with things that are small, weak, soft,

pastel-colored, or sensually curved generally associated with feminine qualities.

The Picturesque: Gilpin

Roughness/ruggedness Subjects: Examples of picturesque

Ruined architecture Disheveled hair Patriarchal head Human body, esp. in action Animals: worn-out carthorse, cow, goat, ass, colors on

birds Smooth stallion is beautiful

Picturesque: Gilpin, cont.

Examples (cont.): lakes

Execution: free and bold Composition: variety of parts united

Shapes Light and shadow Color

Cause: indeterminate

The Picturesque: Price

Roughness, sudden variation (4) Associated with ruins, not with “the highest order

of created beings” (8) Examples:

Gothic architecture Hovels, mills, insides of old barns, stables, etc. “limbs of huge trees shattered by lightning or

tempestuous winds” (6) Animals: Ass, sheep, deer, lion (more than lioness)

ruffled birds (6-8) People: gypsies and beggars (8)

Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex (1816)

Constable, The Haywain, 1821

Thomas Cole, The Oxbow (1836)

Turner

Turner, The Slave Ship, 1840

Friedrich

Earlier 19th C. American Literature and Painting

The American Landscape

Cole, The Oxbow (1836)

American Landscape Painting In the U.S. before 1820, landscape painting

was considered inferior to history painting and portraiture.

Landscape paintings were informational views of estates or cities: they were not considered great art.

Benjamin West, Death of General Wolfe (1770)

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington (1795)

Francis Guy, Pennington Mills, Jones Falls, Baltimore, View Upstream (c. 1804)

American Landscape Painting However, between the 1820s and the Civil

War, landscape painting became the most important genre of American painting—the genre most associated with American identity.

Thomas Cole was largely responsible for this change.

Thomas Cole (1801-1845)

Born in England Moved to U.S. in 1818 Largely self-taught First member of the

“Hudson River School” of painting

Cole’s Landscapes

Emphasize the grandeur and wildness of the American landscape

Apply the European concepts of the sublime and the beautiful to the American landscape

Balance the powers of nature with the powers of civilization

Cole, Falls of Kaaterskill (1826)

Cole, View of Schroon Mountain (1838)

European Landscape Tradition The Beautiful: associated with classical

ideas of order, clarity, and harmony

The Sublime: associated with horror, pain, danger, lack of clarity, disharmony

Claude Lorraine, Landscape with Dancing Figures (1648)

Salvator Rosa, Bandits on a Rocky Coast (17th C.)

Cole, The Oxbow (1836)

Cole, The Oxbow (1836)

Cole, View on the Catskill, Early Autumn

(1837)

Cole, River in the Catskills (1843)

George Inness, The Lackawanna Valley (c. 1856)

Transcendentalism and Luminism

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

Lankford, Baltimore Albion Quilt, c.1850

Hicks, Peaceable Kingdom, c.1834

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel:Dialectic Thesis-------------------------Antithesis

Synthesis

Dialectic: Example

Thesis: Jimmy Carter

Antithesis: Ronald Reagan

Synthesis: Bill Clinton

Dialectic: Example

Thesis: Louis XVI

Antithesis: French Revolution, Reign of Terror

Synthesis: Napoleon

Dialectic: Example

Thesis: Inductive Method of Bacon

Antithesis: Deductive Method of Descartes

Synthesis: Sir Isaac Newton combines inductive and deductive thinking (see 589)

Dialectic: Example

Thesis: Renaissance Style

Antithesis: Baroque Style

Synthesis: Wren’s English Baroque

St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome

Borromini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome, 1667

Christopher Wren,St. Paul’s Cathedral, London (1675-1710)

Dialectic: Example

Thesis: Human Being

Antithesis: Nature

Synthesis: Humanity combined with Nature

Thomas Cole, The Oxbow (1836)

Dialectic: Example

Thesis: The Beautiful

Antithesis: The Sublime

Synthesis: The Picturesque