Role of Early Diagnosis and Multimodal Treatment in Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis: Experience of 4...

-

Upload

kavitha-prasad -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

2

Transcript of Role of Early Diagnosis and Multimodal Treatment in Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis: Experience of 4...

ti

vnots

r7asva

bdm

0

d

J Oral Maxillofac Surg70:354-362, 2012

Role of Early Diagnosis and MultimodalTreatment in Rhinocerebral

Mucormycosis: Experience of 4 CasesKavitha Prasad, MDS,* R. M. Lalitha, MDS,† E. K. Reddy, MSc,‡

K. Ranganath, MDS,§ D. R. Srinivas, MSc,�

and Jasmeet Singh, MDS¶dbb

Mucormycosis is an acute, uncommon opportunisticfungal infection seen primarily in patients with poorlycontrolled diabetes mellitus.1-7 It is a rare fungal infec-ion but has been reported with increasing frequency inmmunocompromised patients and is potentially lethal.1

Mucormycosis caused by order Mucorales, a ubiquitoussaprophytic mold found in soil and organic matterworldwide, is a rare but invasive opportunistic fungalinfection.1 It occurs in 2 main forms, superficial andisceral. The visceral form, which affects the head andeck region, is most commonly encountered by theral and maxillofacial surgeon. Due to its lethal na-ure, it must be recognized early and treated aggres-ively.1,3-5,8 Appropriate management results in a cure

in only about half of rhinocerebral infections.1 Theeported survival rate is variable, ranging from 20% to0%. Management of the condition includes early di-gnosis, initiation of medical therapy, and aggressiveurgical debridement, which requires teamwork byarious disciplines to attain an improved and favor-ble prognosis.

The present report presents 4 cases of rhinocere-ral mucormycosis (RCM) with various aspects of theisease, with a special focus on multimodal manage-ent.

Received from the MS Ramaiah Dental College, Bangalore, India.

*Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

†Professor and Department Head, Department of Oral and Max-

illofacial Surgery.

‡Professor and Department Head, Department of Otolaryngol-

ogy.

§Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

�Assistant Professor, Department of Otolaryngology.

¶Postgraduate Student, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial

Surgery.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr Singh: Post-

graduate, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, MS Rama-

iah Dental College, MSRIT, Post, Bangalore 560054, India; e-mail:

[email protected], [email protected]

© 2012 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

278-2391/12/7002-0$36.00/0

foi:10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.017

354

Report of Cases

CASE 1A 57-year-old man, a known diabetic for 10 years, on

medication (metformin 10 mg twice daily), reported to theDepartment of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, MS RamaiahDental College, with the chief complaint of pain in theanterior region of the left upper and lower jaws for 1month. Swelling was present in the same region for theprevious 1 week, as was a decrease in vision. Examinationshowed diffuse swelling on the left side of the face, perior-bital edema, decreased vision, ptosis, proptosis, dilated pu-pil, and restricted eye movements (Figs 1, 2). Waters viewradiograph showed haziness of the maxillary sinus. Mag-netic resonance imaging (MRI) showed involvement of theleft paranasal sinuses (Fig 3). Random blood glucose levelwas 392 mg/dL, with a fasting blood glucose level of 275mg/dL. Initially antibiotic therapy was started because ofsuspected bacterial infection. As the patient did not re-spond to treatment, a fungal infection was considered and anasal swab was sent for culture.

Blood glucose levels were controlled by administration ofinsulin (injected Actrapid plus human insulin on a slidingscale; Novo Nordisk India Ltd, Mahasena, Gujarat, India)with physician consultation. Surgical debridement of theparanasal sinuses was performed with functional endo-scopic sinus surgery by otolaryngologists. The patient wasadministered amphotericin B (AmB) infusion. The ophthal-mologist’s opinion for extraocular muscle weakness wassought; however, the patient’s vision had returned to nor-mal. The physician’s opinion was sought at regular intervalsfor blood glucose and renal function. The patient re-sponded to the therapy and recovered with minimal mor-bidity. Eye movements were also restored at the end oftreatment.

CASE 2A 45-year-old woman reported to the Otolaryngology

Department, MS Ramaiah Medical Teaching Hospital withthe chief complaint of nasal regurgitation of food and pu-rulent discharge through the eyes and nose and an inabilityto open the right eye for the previous 15 days. On exami-nation, eschars of the right nasal septum were seen withexposure of bone, and ptosis was present. Purulent dis-charge in relation to right eye was also observed, with aninability to separate the eyelids. Intraoral examinationshowed an oval perforation of the hard palate (3 � 2 cm in

iameter) forming an oronasal fistula (Fig 4) covered with alack necrotic mass. Although she was not a known dia-etic, her random blood sugar level was 419 mg/dL and her

asting blood sugar level was 300 mg/dL. Waters view ra-

PRASAD ET AL 355

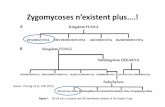

diograph showed thickening of the sinus lining, with hazi-ness of the sinus. Computerized tomographic (CT) scanshowed pansinusitis with palatal erosion. Biopsy at the timeof surgical debridement showed the presence of Zygomy-cetes hyphae.

The physician’s opinion was sought for the increasedblood glucose, and the patient was started on insulin. Reg-ular monitoring for electrolytes and serum creatinine wasperformed. The ophthalmologist’s opinion was sought for

FIGURE 1. Case 1. Clinical photograph showing diffuse swellingon the left side of face, periorbital edema, and ptosis.

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg2012.

FIGURE 2. Case 1. Clinical photograph showing a dilated pupilon everting the upper eyelid.

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg

2012.the vision of the right eye. Light reflex was absent. Aggres-sive surgical debridement and orbital exenteration wasplanned and performed; AmB infusion was started. Afterthis combined medical and surgical treatment, the patientshowed improvement. An obturator was fabricated by theprosthodontist to cover the palatal defect.

FIGURE 3. Case 1. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imageshowing involvement of the left paranasal sinuses (arrow).

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg2012.

FIGURE 4. Case 2. Intraoral photograph showing defect on thehard palate.

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg

2012.

gDo

wMbpfs(s

swdTrat

byb

r

356 RHINOCEREBRAL MUCORMYCOSIS

CASE 3A 27-year-old, otherwise healthy prima gravida of 35

weeks, presented to the Department of Obstetrics and Gy-necology, MS Ramaiah Medical Teaching Hospital with pre-eclampsia and intrauterine fetal demise. She was admittedto the hospital but 12 days later developed renal failure,disseminated intravascular coagulation, and sepsis. She wassubsequently intubated when she became unresponsive.One week after intubation, the patient developed swellingon the right side of the face and a referral to the Departmentof Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, MS Ramaiah Dental Col-lege was given. On examination, facial swelling extendingfrom the right upper lip to the infraorbital region was seen,with a black crust over the nasal mucosa. Intraorally, palatalnecrosis and premaxillary segment mobility was observed.The swelling later extended bilaterally, involving the perior-bital region, cheeks, and lips (Fig 5). CT scan showed theerosion of the nasal floor and premaxilla, with an extension tothe alveolus (Fig 6).

A nasal swab was sent for culture and nasal biopsyshowed the presence of Mucor fungal hyphae (Fig 7). Sur-ical debridement was performed and AmB infusion started.espite this treatment, the patient died after 3 days becausef cerebral involvement.

CASE 4A 15-year-old girl with known acute lymphoid leukemia

as referred to the Department of Pediatrics, MS Ramaiahedical Teaching Hospital with complaints of difficulty inreathing and dizziness. On reporting to the hospital, theatient became unconscious. Clinical examination showed

acial edema, black nasal eschars, and palatal necrosis. CTcan showed pansinusitis with erosion of the left nasal wallFig 8) and histopathology confirmed the presence of non-eptate hyphae of Zygomycetes.

FIGURE 5. Case 3. Clinical photograph showing bilateral perior-bital, infraorbital, and lip swelling.

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg

2012.This patient had a very rapid progression of disease. Theecond day after admission, she became unresponsive andas intubated. The pediatric oncologist’s opinion was un-erlying leukemia that could not be effectively controlled.he patient’s serum creatinine levels became high with theecommended dose of AmB; therefore, a lower dosage wasdvised. Surgical debridement could not be performed, andhe disease course was fatal.

Discussion

Mucormycosis, also known as zygomycosis andphycomycosis, was first described by Paulltauf in1885.9 It can occur in any age group. The age distri-

ution in the present cases ranged from 15 to 57ears, with 3 female patients and 1 male patient (Ta-le 1).There are at least 6 clinical forms of mucormycosis:

hinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointesti-

FIGURE 6. Case 3. Computed tomogram showing erosion of thepremaxilla with extension to the alveolus.

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg2012.

FIGURE 7. Case 3. Histopathologic image showing nonseptatefungal hyphae branching at a right angle (arrow).

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg

2012.

uiml

PRASAD ET AL 357

nal, central nervous system, disseminated, and miscel-laneous (eg, bone or kidney).1,8,10

RHINOCEREBRAL MUCORMYCOSIS

The term rhinocerebral mucormycosis should besed only if the orbit, paranasal sinuses, and brain are

nvolved. RCM is the most common and most fatalanifestation and is further divided into rhinomaxil-

ary, rhino-orbital, and rhinocerebral.11

FIGURE 8. Case 4. Computed tomogram showing involvement ofmaxillary sinus bilaterally.

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg2012.

Table 1. SUMMARY OF CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS AND

Case Age/Gender Clinical Symptoms Underlying Disea

1 57 yrs/male Pain in upper and lowerjaw, facial swelling,decreased vision

Uncontrolled diabe

2 45 yrs/female Nasal regurgitation offood, purulentdischarge throughright eye and nose,inability to open eye,oronasal fistula

Uncontrolled diabe(not a knowndiabetic)

3 27 yrs/female Facial swelling,premaxillary segmentmobility, black palataleschar

Prolonged stay inintensive care u

4 15 yrs/female Facial edema, blackpalatal eschar, palatalnecrosis

Hematologicmalignancy (aculymphoidleukemia)

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012

PULMONARY MUCORMYCOSIS

Pulmonary zygomycosis is more common in neu-tropenic patients with underlying hematologic malig-nancies or who undergo hematopoietic stem celltransplantation. Its clinical and radiologic features areindistinguishable from those of invasive pulmonaryaspergillosis. Patients present with prolonged feverthat is unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics,nonproductive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and dete-riorating dyspnea. Pulmonary zygomycosis can spreadto other organs if not promptly treated and is associ-ated with a high case-fatality rate.10

CUTANEOUS MUCORMYCOSIS

Primary cutaneous zygomycosis is associated withtraumatic inoculation of the skin with Zygomycetes inimmunocompromised patients, burn victims, and pa-tients with severe soft tissue trauma. Necrotic escharsare the diagnostic hallmark and should prompt animmediate biopsy of the involved skin and subcuta-neous fat.10

GASTROINTESTINAL MUCORMYCOSIS

Gastrointestinal zygomycosis is uncommon and hasbeen mainly described in premature neonates, whereit presents as necrotizing enterocolitis with a swollen,erythematous, and tender abdomen. The disease ischaracterized by fungal invasion into the gut mucosa,submucosa, and blood vessels. Gastrointestinal perfo-ration can lead to peritonitis, with a high mortalityrate.10

DISSEMINATED MUCORMYCOSIS

Disseminated zygomycosis is usually the result ofdissemination from invasive pulmonary disease, al-though it may originate from any of the primary sites

AGEMENT IN THE PRESENT CASES

Extent ofInvolvement Treatment Outcome

Pansinusitis, orbitalinvolvement

Control of underlying predisposingcondition, extensive surgicaldebridement, amphotericin B

Recovered

Pansinusitis withpalatal erosion,orbitalinvolvement

Control of underlying predisposingcondition, extensive surgicaldebridement, orbitalexenteration, amphotericin B,fabrication of palatal obturator

Recovered

Erosion of nasalfloor, premaxillaextending toalveolus

Extensive surgical debridement,removal of necrotic premaxillarysegment, amphotericin B

Died

Pansinusitis witherosion of leftnasal wall

Amphotericin B, control ofunderlying predisposingcondition surgical debridementcould not be performed

Died

MAN

se

tes

tes

nit

te

.

mRc

lcipwi

358 RHINOCEREBRAL MUCORMYCOSIS

of infection. Most cases are diagnosed by postmortemexamination of profoundly immunosuppressed pa-tients. However, several cases of disseminated zygo-mycosis have been described in immunocompetentindividuals after life-threatening multiple injuries tovarious organs. The death rate approaches 100%.1,10

RARE FORMS OF MUCORMYCOSIS

A rare manifestation of zygomycosis is a primaryrenal form that is usually confirmed at autopsy exam-ination. Although rare, bilateral renal zygomycosisshould be suspected in any immunocompromised pa-tient who presents with hematuria, flank pain, andunexplained anuric renal failure.

CAUSATIVE ORGANISM

Of the approximately 300,000 known fungal spe-cies, about 200 have been described as pathogens ofhuman disease. Of these, less than 10% are so-calledpathogenic fungi that cause invasive illnesses.12 These

ost commonly include species of Rhizopus, Mucor,hizomucor, and Cunninghamella and rarely in-lude Apophysomyces, Saksenaea, and Absidia. Rhi-

zopus and Mucor belong to the order Mucorales ofthe family Zygomycetes. Zygomycetes have a widegeographic distribution, are all thermotolerant, anduse a variety of nutritional substrates.1,12 In nature,they are found in the soil, animal feces, and decayingplant materials. Nosocomial infections can occurthrough sporangiospores released from contaminatedair-conditioning systems or contaminated wound dress-ings. These molds have broad, rarely septate, hyphaeof uneven diameters ranging from 6 to 50 �m, withong sporangiophores attached.1 The fungus is diffi-ult to grow from infected tissue, but when it grows,t is rapid and profuse on most media at room tem-erature. It must be distinguished from Aspergillus,hich is smaller and septate, with more acute branch-

ng.1 Infection in humans is thought to be caused byasexual spore formation. The tiny spores then be-come airborne and land on the oral and nasal mucosaof humans. In the vast majority of immunologicallycompetent hosts, these spores will be contained by aphagocytic response. If this fails, germination willensue and hyphae will develop. As the polymorpho-nuclear leukocytes are less effective in removing hy-phae, the infection can then become established. Itprogresses as the hyphae begin to invade arteries,where they propagate within the vessel walls andlumens, causing thrombosis, ischemia, and infarction,with dry gangrene of the affected tissues.1

Scedosporium apiospermum is an emerging fungalpathogen that has occasionally been reported tocause localized soft tissue infection in normal hostsand invasive or disseminated infection in immuno-

compromised patients, with a usually rapidly progres-sive and fatal outcome. The management of invasiveS apiospermum is complex, secondary to its resis-tance to multiple antifungal agents, including AmBand fluconazole.13

The causative organism in 3 of the present caseswas identified as Mucor.

PORTAL OF ENTRY

The portals of entry of Zygomycetes are usually therespiratory tract, the skin, and, less frequently, thegut.10 Sporangiospores may be released from contami-nated air-conditioning systems or contaminated wounddressings. It can rarely be transmitted because oftrauma,12 dental extractions,11 intramuscular injec-tions to infected wounds, insect bite, intravenousdrug abuse, prosthetic devices, etc.2

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

Although mucormycosis is ubiquitous and growsrapidly, it rarely causes infection in immunocompe-tent patients. These healthy individuals are wellequipped against the attack of the fungi by the barrierfunction of the skin and mucosa and by the native andadaptive immune response.

Risk factors associated with mucormycosis includeprolonged neutropenia; use of corticosteroids; hemato-logic malignancies (leukemia, lymphoma, and multiplemyeloma); aplastic anemia; myelodysplastic syndromes;solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation;human immunodeficiency virus infection; diabeticand metabolic acidosis; iron overload; deferoxamineuse; burns; wounds; malnutrition; extremes of age, ie,prematurity or advanced age; and intravenous drugabuse.1,2,3,10 In individuals with multiple injuries re-quiring long-term intensive care, presence of 1 ormore risk factor favors the development of an invasivefungal infection.14

Foreign bodies also favor the establishment of fun-gal colonies, leading to chronically progressive infec-tion and tissue destruction in immunocompromisedpersons.

Deferoxamine is used as a chelating agent for iron andaluminum in patients undergoing hemodialysis and hasbeen associated with a fulminant form of mucormycosis.Iron appears to be an important growth factor for Mu-corales. Transferrin, which binds serum iron, deprivesfungi and other pathogens of this nutrient. To obtainiron, micro-organisms secrete iron-binding compoundsknown as siderophores. The iron bound to thesesiderophores can be used by the fungi, whereas ironbound to transferrin cannot. Thus, deferoxamine, inthe iron-chelate form, ferrioxamine, provides iron toMucorales. Iron-catalyzed peroxidase production offree radicals (which is important for killing fungi) maybe inhibited by deferoxamine, further potentiating

infection.1,8

P2

PRASAD ET AL 359

The predisposing factors in the present case serieswere uncontrolled diabetes mellitus in 2 cases, pro-longed stay in an intensive care unit and medicalcompromise in 1 case, and hematologic malignancy in1 case.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Roden et al15 have reviewed all published reportsof zygomycosis in the English-language literaturesince 1885. In total 929 eligible cases were reviewed.The mean age of patients was 38.8 years, and 65% ofpatients were male. The most common types of in-fection were sinus (39%), pulmonary (24%), and cu-taneous (19%). Dissemination developed in 23% ofcases.15 The characteristic clinical picture of RCMincludes low-grade fever, sinusitis, unilateral facialswelling, black nasal or palatal eschars (Figs 9, 10),decreased vision, and ophthalmoplegia.1,10 Necroticeschars in the nasal cavity, the turbinates, or thepalate and necrotic facial lesions signify aggressiveangioinvasive infections. Pain and swelling precedeoral ulceration. Progressive tissue necrosis can lead topalatal perforation. The infection can extend from thesinuses into the mouth and produce painful, necroticulcerations of the hard palate. Once established in theparanasal sinuses, the infection can easily spread toand enter the orbit through the nasolacrimal duct andmedial orbit. Spread to the brain may occur throughthe orbital apex, orbital vessels, or cribriform plate.As the disease progresses to the orbit and skull, thepatient may become confused, obtunded, and coma-tose. Superior orbital fissure syndrome (unilateral sen-sory deficit of the first and second divisions of thetrigeminal nerve and ophthalmoplegia), chemosis,and proptosis result from vascular compromise andinfection of the orbital contents.1,8,10 A bloody nasal

FIGURE 9. Clinical photograph showing necrotic palataleschar.

Prasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac

Surg 2012.discharge may be the first sign that infection hasinvaded through the turbinates and into the brain.Fungal invasion of the globe or retinal artery leads toblindness. Intracranial complications include caver-nous and, more rarely, sagittal sinus thrombosis andepidural or subdural abscess formation. Extensioninto the cavernous sinus and involvement of the in-ternal carotid artery can result in cerebral ischemia,brain infarction, and ultimately death.

INVESTIGATIONS

Plain orbit or sinus radiography is frequently non-specific and shows nodular thickening of the sinuslining and cloudy sinuses without fluid levels. Itshows spotty destruction of sinus bony wall, whichmimics chronic sinusitis.1,10

Computed tomography is a sensitive indicator ofthe extent of orbital and cranial involvement. It typi-cally shows opacification of the paranasal sinuses andthickening of the sinus mucosa and bone destruction,without an air-fluid level. In addition, CT scan willshow soft tissue swelling, proptosis, and swelling ofthe extraocular muscles. CT scanning may be partic-ularly useful in determining the extent of necrosis.Although sinus computed tomography is the pre-ferred imaging modality, bony destruction is oftenseen only late in the course of the disease, after softtissue necrosis has already occurred.1,8

Some investigators favor the use of MRI because of

FIGURE 10. Specimen showing excised black necrotic eschar.

rasad et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg012.

the susceptibility of vascular and other soft tissue

ps

Aiotiullbg6p

btdt

360 RHINOCEREBRAL MUCORMYCOSIS

structures to fungal invasion. Reports have suggestedthat T2-weighted MR images are appropriate for dem-onstrating intracerebral extension and enhanced im-ages may help detect early vascular invasion. In viewof the rapid progress and invasiveness of the infec-tious process, CT or MR scans should be obtained atfrequent intervals to monitor disease extension andresponse to therapy. Also, MRI may be the preferredchoice to contrast computed tomography because ofthe coincident use of nephrotoxic drugs and presenceof compromised renal function. Perineural spread ofthe disease can also be demonstrated with contrast-enhanced MRI scans.1,8,16

In areas of anatomic complexity, especially the or-bit, reactive inflammation may be difficult to distin-guish from true invasion with computed tomographyor MRI. In these instances, angiography or surgicalexploration may provide crucial diagnostic informa-tion. In patients with intracranial involvement, cere-brospinal fluid sampling is usually nonspecific andunhelpful.

Given the limitations of imaging studies, the goldstandard of diagnosis is pathologic examination onpermanent sections. Stains of fixed tissues with he-matoxylin and eosin or specialized fungal stains, suchas Grocott methenamine-silver or periodic acid-Schiffstains, show broad-based, ribbonlike, nonseptate hy-phae with wide-angle branching (approximately 90°);there are no reliable serologic, polymerase chain re-action-based tests or skin tests for mucormycosis.However, permanent section can be a lengthy andtime-consuming means to obtain the diagnosis, delay-ing appropriate treatment and increasing the morbid-ity and mortality of the disease.1

Frozen sections at the time of the original biopsyhave been recommended to obtain an earlier diagno-sis so that medical treatment can begin as soon aspossible in the event of a positive diagnosis. Frozensection is useful in diagnosis and even during surgicaldebridement. It can be used to prevent more exten-sive surgical debridement by providing intraoperativenegative margins and in the follow-up of patients inthe outpatient setting while they receive antifungaltherapy.4

Cultures should be attempted, although they areinfrequently positive and speciation has no impact ontreatment and prognosis. A fresh tissue preparationusing 10% to 20% potassium hydroxide can providerapid diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is suggested by combination of arapidly progressive infection and a black necroticmass of tissue filling the nasal cavity, eroding the nasalseptum, and extending through the hard palate in

immunocompromised patients. The gold standard of gdiagnosis is pathologic examination on permanentsections.1-3,8,10,12 However, the main cause of delay indiagnosis is lack of differentiation from bacterial in-fection on first presentation. The distinction must bemade by the presence of redness, swelling, purulentdischarge, and pain in bacterial infections comparedwith persistent soft tissue lesion, moderate pain, andprogressive loss of function in fungal infections.12

Due to extensive necrosis, RCM may assume thepresentation of malignancy, syphilis, tuberculosis,midline lethal granuloma syndrome, Wegener granu-lomatosis, aspergillosis, and other systemic myco-ses.17

Given the rapidly progressive nature of RCM andthe marked increase in mortality when the funguspenetrates the cranium, any diabetic patient witha headache and visual changes is a candidate forprompt evaluation, which should include imagingstudies and nasal endoscopy to rule out mucormyco-sis.

The prognosis is usually poor, with high mortalityrates, which are influenced by the timeliness of diag-nosis and, above all, by the patients’ systemic status.The mortality of mucormycosis associated with hema-tologic malignancy despite treatment is higher than60%. This mortality increases to 100% in pediatrichematologic patients with RCM. However, with earlydiagnosis and aggressive treatment, prognosis can beimproved.

TREATMENT

A combination of radical surgical debridement andsystemic antifungal therapy is the currently followedregimen.1,2,5,6,8,10,11,13,17 The treatment is multidisci-

linary, with each speciality having an important andpecific role.

Mucormycosis is a medical emergency. The use ofmB (1 mg/kg/d intravenously) has been the mainstay

n the treatment of mucormycosis, with a survival ratef up to 72%. Although toxic to the patient, a long-erm course of AmB is necessary to eradicate thisnfection; the duration and total dose must be individ-alized in each case. When the serum urea nitrogen

evel exceeds 40 mg/100 mL or the serum creatinineevel exceeds 3.0 mg/100 mL, consideration shoulde given to temporarily decreasing the dosage. Ineneral, a total dose of 3 to 4 g should be given overto 12 weeks. Small doses administered over a long

eriod help to minimize toxicity and side effects.1

Most negative side effects of AmB can be avoidedusing lipid preparations of AmB.1,8,18,19 This lipid-

ased formulation increases circulation time and al-ers the biodistribution of the associated AmB. As therugs complexed with lipid vehicles remain longer inhe vasculature, they are able to localize and reach

reater concentrations in tissues in which infection

boi

p

ti

PRASAD ET AL 361

and inflammation are present. Normal tissues are es-sentially impermeable to lipid-complexed drugs. Fur-thermore, the 50% lethal dose of lipid-based AmB isapproximately 10 to 15 times higher than that ofconventional AmB and has substantially decreasedrenal toxicity. The recommended dose of liposomalAmB is 5 mg/kg/d prepared as a 1-mg/mL infusion anddelivered at a rate of 2.5 mg/kg/hour. Salvage po-saconazole therapy for refractory mucormycosis hasalso been reported.8

The echinocandins are a class of antifungal medica-tions with activity against the synthesis of �-(1,3)-D-glucan, a major fungal cell wall component. Caspo-fungin, which belongs to this group, is effective incombination with AmB for the treatment of zygomy-cosis in murine models.20 Caspofungin has a favorableside effect profile because the target enzyme of thedrug is not present in mammalian cells. It has fewsignificant drug interactions because it is neither asubstrate nor an inhibitor of cytochrome P450.21

However, clinical experience with caspofungin is ex-tremely limited and there is a lack of sufficient evi-dence of its benefits in RCM.

Surgery needs to be radical, with an aim to removeall devitalized tissue, and has to be repeated based ondisease progression. In some cases, radical resectionmay be required, which can include partial or totalmaxillectomy, mandibulectomy, and orbital exenter-ation.5 This includes resection of involved tissues ofthe face, including skin and muscle, thorough de-bridement of maxillary and ethmoid sinuses, necrotictissue in the temporal area and infratemporal fossa,and orbital exenteration.8 Orbital exenteration may

e life saving in the presence of active fungal invasionf the orbit and should be considered for an actively

nfected orbit with a blind, immobile eye.1 It has beenconsidered helpful even after intracranial spread hasoccurred. Whether to perform orbital exenteration isthe most difficult decision in the surgical managementof orbital mucormycosis because the procedure mayrepresent a life saving measure achieved at the cost ofpermanent mutilation.20 Surgical debridement usually

roceeds quickly because of an almost bloodless field.Hyperbaric oxygen therapy aids neovasculariza-

ion, with subsequent healing in poorly perfused ac-dotic and hypoxic but viable areas of tissue.21 Hyper-baric oxygen therapy for mucormycosis shouldconsist of exposure to 100% oxygen for 90 minutes to2 hours at pressures from 2.0 to 2.5 atm with 1 or 2exposures daily, for a total of 40 treatments. Althoughhyperbaric oxygen is offered by only a few medicalfacilities, it may be warranted in patients who appearto be deteriorating despite maximal surgical and med-ical therapy.

Other experimental therapies for RCM have been

reported, with varying success.22,23 These includenebulized/local irrigation with AmB, topical hydrogenperoxide, and the combination of AmB with flucyto-sine, rifampin, or fluconazole. Other drugs such asanticoagulants and steroids alone or in combinationhave been used, with variable success. However,most of these have been cited in single case reports.

ROLE OF VARIOUS SPECIALITIES

The patient can initially report to the oral andmaxillofacial surgeon, otolaryngologist, ophthalmolo-gist, physician, or neurosurgeon depending on thesymptoms. A thorough medical history and carefulclinical examination with astute observation for anypeculiar feature will help in early recognition andprompt referral. Coordination between the variousspecialists with support from radiology, microbiol-ogy, and pathology is required to initiate early treat-ment. Medical treatment performed in associationwith a physician and a nephrologist is the mainstay oftreatment, with adjunctive surgical debridement inestablished disease.

Although the emphasis was given to early recogni-tion of the disease with aggressive and prompt treat-ment to yield favorable results, 2 cases still had fataloutcomes.

This discussion raises the point that the astute cli-nician must entertain the possibility of mucormycosisin the differential diagnosis of all immunocompro-mised patients with sinus, nasal, oral, or orbital com-plaints, despite an innocuous appearance at the bed-side or on CT scan. This will enable timely andappropriate referral so that early diagnosis is achievedand prompt intervention can be initiated to improveprognosis.

References1. O’Neill BM, Alessi AS, George EB, et al: Disseminated rhinoce-

rebral mucormycosis: A case report and review of the litera-ture. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 64:326, 2006

2. Schütz P, Behbehani JH, Khan ZU, et al: Fatal rhino-orbito-cerebral zygomycosis caused by Apophysomyces elegans in ahealthy patient. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 64:1795, 2006

3. Dhong H, Lanza D: Fungal rhinosinusitis, in Kennedy D, Zin-reich J, Bolger W (eds): Diseases of the Sinuses. Cambridge,Blackwell Science, 2001, p 179

4. Ghadiali MT, Deckard NA, Farooq U, et al: Frozen-sectionbiopsy analysis for acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolar-yngol Head Neck Surg 136:714, 2007

5. Tryfon S, Stanopoulos I, Kakavelas E, et al: Rhinocerebral mu-cormycosis in a patient with latent diabetes mellitus: A casereport. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 60:328, 2002

6. Jung S-H, Kim SW, Park CS, et al: Rhinocerebral mucormycosis:Consideration of prognostic factors and treatment modality.Auris Nasus Larynx 36:274, 2009

7. Lanternier F, Lortholary O: Zygomycosis and diabetes mellitus.Clin Microbiol Infect 15:21, 2009 (suppl 5)

8. Rapidis AD: Orbitomaxillary mucormycosis (zygomycosis) andthe surgical approach to treatment: Perspectives from a max-illofacial surgeon. Clin Microbiol Infect 15:98, 2009 (suppl 5)

9. Paulltauf A: Mycosis mucorina. Virchows Arch A 102:543, 1885

362 RHINOCEREBRAL MUCORMYCOSIS

10. Mantadakis E, Samonis G: Clinical presentation of zygomycosis.Clin Microbiol Infect 15:15, 2009 (suppl 5)

11. Kim J, Fortson JK, Cook HE: A fatal outcome from rhinocere-bral mucormycosis after dental extractions: A case report.J Oral Maxillofac Surg 59:693, 2001

12. Hajdu S, Obradovic A, Presterl E, et al: Invasive mycoses fol-lowing trauma. Injury 40:548, 2009

13. Shand JM, Albrecht RM, Burnett HF III, et al: Invasive fungalinfection of the midfacial and orbital complex due to Scedospo-rium apiospermum and mucormycosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg62:231, 2004

14. Eggimann P, Garbino J, Pittet D: Epidemiology of Candidaspecies infections in critically ill non-immunosuppressed pa-tients. Lancet Infect Dis 3:685, 2003

15. Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al: Epidemiology andoutcome of zygomycosis: A review of 929 reported cases. ClinInfect Dis 41:634, 2005

16. Press GA, Weindling SM, Hesselink JR, et al: Rhinocerebral

mucormycosis: MR manifestations. J Comput Assist Tomogr12:744, 198817. Economopoulou P, Laskaris G, Ferekidis E, et al: Rhinocerebralmucormycosis with severe oral lesions: A case report. J OralMaxillofac Surg 53:215, 1995

18. Walsh TJ, Hiemenz JW, Seibel NL, et al: Amphotericin B lipidcomplex for invasive fungal infections: Analysis of safety andefficacy in 556 cases. Clin Infect Dis 26:1383, 1998

19. Spellberg B, Fu Y, Edwards JE, et al: Combination therapy withamphotericin B lipid complex and caspofungin acetate of dis-seminated zygomycosis in diabetic ketoacidotic mice. Antimi-crob Agents Chemother 49:830, 2005

20. Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP: Editorial commentary: What is therole of combination therapy in management of zygomycosis?Clin Infect Dis 47:372, 2008

21. Petrikkos G, Skiada A: Recent advances in antifungal chemo-therapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents 30:108, 2007

22. Greenberg RN, Scott LJ, Vaughn HH, et al: Zygomycosis (mu-cormycosis): Emerging clinical importance and new treat-ments. Curr Opin Infect Dis 17:517, 2004

23. Tragiannidis A, Groll AH: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy and other

adjunctive treatments for zygomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect15:82, 2009 (suppl 5)

![Monitoria multimodal cerebral multimodal monitoring[2]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/552957004a79599a158b46fd/monitoria-multimodal-cerebral-multimodal-monitoring2.jpg)