Risk Factors for Hypertension in a National Cohort...

Transcript of Risk Factors for Hypertension in a National Cohort...

598

Risk Factors for Hypertension ina National Cohort Study

Earl S. Ford and Richard S. Cooper

Hypertension continues to be a major public health problem in the United States. We used datafrom the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Followup Study(1971-1984) to examine predictors of hypertension for the 7,073 participants free fromhypertension at the baseline examination. The follow-up period averaged 10 years. Body massindex was positively related to the probability of hypertension developing among white men(n=2,370), white women (n=3,949), black men (n=231), and black women (n=523). Educationwas inversely associated with the probability of hypertension developing among white womenand was of borderline significance among white men and black women. In a subanalysis ofwhite men (n = l,790) and white women (n=3,063) who completed the 24-hour recall dietaryquestionnaire, dietary consumption of sodium, calcium, and potassium did not predict thedevelopment of hypertension. The failure of our study to support findings relating intake ofdietary cations to the development of hypertension may be attributable to imprecision in themeasurement of dietary data and misclassification of hypertension status. These data reinforcethe importance of weight control in the primary prevention of hypertension. (Hypertension1991;18:598-606)

Hypertension is a major public health problemin the United States, with 57,100,000Americans estimated to have the disease.1

Despite extensive research into the etiology andcontributing causes of essential hypertension, thepathogenesis of the condition is still not explained.Nonpharmacological approaches to the treatment ofhypertension have included a reduction of salt intakeand increases in dietary potassium and calcium con-sumption, weight loss, and increased physical activity.Although the small reductions in blood pressurefrom these nonpharmacological measures could the-oretically have important beneficial public healthconsequences,2 it has not been shown that theseapproaches can serve as primary measures to retardor prevent the onset of hypertension in the generalpopulation.

Most of the available data have come from cross-sectional and experimental studies. However, determi-nants of blood pressure have been examined in fewprospective studies. We studied the relations of severalsociodemographic, behavioral, and biochemical param-eters on the incidence of hypertension among a group

From the Division of Diabetes Translation, Center for ChronicDisease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for DiseaseControl, Atlanta, Ga., and the Department of Preventive Medicineand Epidemiology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, 111.

Address for correspondence: Earl Ford, MD, MPH, Division ofDiabetes Translation, Centers for Disease Control, 1600 CliftonRoad, NE, Mailstop K10, Atlanta, GA 30333.

Received May 10, 1990; accepted in revised form June 27, 1991.

of participants followed from the first National Healthand Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I),which was conducted from 1971 through 1975.

MethodsBetween 1971 and 1975, 20,729 Americans aged

25-74 years participated in the NHANES I study.The plans and operations for the NHANES I andNHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study havebeen published previously.3-6 Of the 14,407 partici-pants who were 25-74 years old at baseline andunderwent a medical examination, 13,380 (92.9%)were successfully traced between 1982 and 1984.7

Among the participants, a more detailed examinationwas performed on 6,913 persons. These included3,059 participants in a 1975 augmentation survey plusa random sample of participants examined from 1971through 1974. Survivors and proxy respondents fordeceased participants and participants incapable ofresponding were interviewed, and blood pressuremeasurements were obtained from survivors. Meanfollow-up time was 10 years for traced participantsstill alive, with a range of 5-12 years. The study andthe confidentiality of the data from the study werethoroughly discussed with the participants. By agree-ing to participate in the study, participants gaveimplied consent.

By design, various subgroups of the final samplecompleted different study components and question-naires. A detailed medical examination was per-

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Ford and Cooper Risk Factors for Hypertension 599

formed on 6,913 persons. This included the 3,059persons from the augmentation survey that was con-ducted from July 1974 through September 1975 aswell as 3,854 randomly sampled persons from partic-ipants between 1971 and 1974.8 Consequently, not allinformation is available for each respondent. Forexample, dietary data were available only for 11,348participants, serum calcium data for 6,913 partici-pants, and serum potassium and sodium data for3,059 participants, whereas serum magnesium datawere available for all participants.

At the baseline examination, a single blood pres-sure measurement was obtained in accordance withAmerican Heart Association criteria.9 We definedhypertension at baseline as a systolic blood pressure(SBP) of greater than or equal to 160 mm Hg, adiastolic blood pressure (DBP) of greater than orequal to 95 mm Hg, or using antihypertensive medi-cation. The latter factor was determined at thebaseline examination, when all participants betweenthe ages of 12 and 74 years were asked, "During thepast 6 months, have you used any medicine, drugs, orpills for high blood pressure?" Participants whoresponded that they regularly or occasionally usedantihypertensive medications were eliminated fromthe analysis, as were participants with missing infor-mation that precluded the establishment of hyperten-sive status. For participants receiving the more de-tailed examination, the wording of the follow-upquestionnaire differed from the original question-naire. First, respondents were asked if they had everbeen told by a doctor that they had hypertension orhigh blood pressure. Those who responded affirma-tively were then asked, "Has a doctor ever prescribedmedicine for your (high blood pressure/hyperten-sion)?" Those who responded affirmatively to thisquestion and replied to a subsequent question thatthey used antihypertensive medication all the time,often, or once in a while, were classified as hyperten-sive and excluded from the analysis.

At the follow-up examination between 1980 and1982, three blood pressure measurements were ob-tained from each living participant where this waspossible. The average SBP and DBP data from thelast two readings were used to determine hyperten-sive status. The same definition (SBP ^160 mm Hg,DBP s95 mm Hg, or the use of antihypertensivemedications) classified participants as hypertensive.

Independent variables were age, income, educa-tion, leisure-time physical activity, non-leisure-timephysical activity, body mass index, blood cholesterollevel, resting pulse rate, alcohol use, and serummagnesium level. For the dietary subanalysis, dietaryintakes of sodium, potassium, and calcium and totalnumber of calories were examined. The continuousvariables of age, income, education, body mass index,and alcohol use were divided into discrete categories,as shown in Table 1. Body mass index was dividedinto three categories. Normal weight was defined asless than 27.8 kg/m2 for men and less than 27.3 kg/m2

for women. Obesity was defined as 27.8 to less than

ScxnmTotal Diet catfom

Prior to deletion 14.407 11.348 3,059

Delete raca other than white or black

14.235 11.214 3.021Delete km to foDowup

Delete p e n o n wtm hypcrteuiooatt

13,243 10/J37 2J06

5.653 1,767

Ddete reconb with r'f'Hiig data

Number of reconb available for anatytb 7.073 5/411 1.548

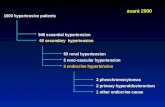

FIGURE 1. Sample sizes available for analysis after variousdeletions, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(NHANES I) Epidemiologic Followup Study, 1971-1984.

31.1 kg/m2 for men and 27.3 to less than 32.3 kg/m2

for women. Severe obesity was defined as 31.1 kg/m2

or greater for men and 32.3 kg/m2 or greater forwomen.10 Alcohol use was calculated as the numberof drinks of alcohol consumed per day. This variablewas categorized as less than 1 drink/day, 1-2 drinks/day, and 3 or more drinks/day. Dietary calcium,potassium, and sodium data were divided into quar-tiles based on the distribution of the entire sample,and the quartile with the lowest consumption wasused as the reference category. Similarly, serumlevels of calcium, potassium, and sodium were di-vided into quartiles based on the distribution of theentire sample, with the lowest serum values used asthe reference category.

To describe differences in categorical baselinevariables among the four race and sex groups, weused log-linear modeling. To test for differences incontinuous variables among the four race and sexgroups, we used analysis of variance. The relation-ship of the study variables to the development ofhypertension was examined in several ways. For eachrace and sex group, we determined the incidence ofhypertension for each level of each study variable.Duferences in hypertension incidence were exam-ined with x1 tests. Furthermore, we used logisticregression analysis to examine the relation betweeneach individual study variable and hypertension sta-tus. To examine the independent association be-tween the study variables and hypertension status,multiple logistic regression analysis was used.

The NHANES I study was designed as a multistage,stratified probability survey. Oversampling of certaingroups (women of childbearing age, the elderly, andpersons living in low-income areas) was performed.Rather than producing national prevalence estimates,we wished to examine relations between risk factorsand mortality in a large community sample and, there-fore, we did not use sample weights.

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

600 Hypertension Vol 18, No 5 November 1991

TABLE 1. Baseline Distribution of Study Variables in the NHANES I Study, 1971-1975

Variable

Age(yr)

25-44

45-64

£65

Income

<S10,000

$10,000-14,999

$15,000-19,999

$20,000-24,999

&$25,000

Education (yr)

<12

12

2:12

Nonleisure-timc physical activity

Very active

Moderately active

Inactive

Leisure-time physical activity

Much exercise

Moderate exercise

Little or no exercise

Weight

Normal weight

Obese

Severe obesity

Alcohol use (drinks/day)

<1

1-2

2=3

Blackmen

(«=231)

n

103

84

44

157

43

16

10

5

133

57

41

131

91

9

50

78

103

174

35

22

187

26

18

%

44.6

36.4

19.1

68.0

18.6

6.9

4.3

2.2

57.6

24.7

17.8

56.7

39.4

3.9

21.7

33.8

44.6

75.3

15.2

9.5

81.0

11J

7.8

Whitemen

(n=2370)

n

1,173

808

389

1,021

675

339

173

162

803

795

772

1,185

988

197

668

987

715

1,873

366

131

1,731

372

267

%

49.5

34.1

16.4

43.1

28.5

14.3

7.3

6.8

33.9

33.5

32.6

50.0

41.7

8.3

28.2

41.7

30.2

79.0

15.4

5.5

73.0

15.7

11.3

Blackwomen(n=523)

n

383

96

44

411

64

33

9

6

270

173

80

243

226

54

49

142

332

318

128

77

475

28

20

%

73.2

18.4

8.4

78.6

12.2

6.3

1.7

1.2

51.6

33.1

15.3

46.5

43.2

10.3

9.4

27.2

63.5

60.8

24.5

14.7

90.8

5.4

3.8

Whitewomen

(n=3,949)

n

2,510

997

442

1,859

1,059

552

257

222

1,198

1,764

987

1,844

1,830

275

659

1,647

1,643

3,138

577

234

3,588

282

79

%

63.6

25.3

11.2

47.1

26.8

14.0

6.5

5.6

30.3

44.7

25.0

46.7

46.3

7.0

16.7

41.7

41.6

79.5

14.6

5.9

90.9

7.1

2.0

Race

03147

0.0001

0.0001

0.2222

0.0001

0.0001

0.0417

p Value

Sex

0.0001

0.0016

0.0001

0.0021

0.0001

0.0020

0.0001

Interaction

0.001

0.0044

0.001

0.0079

ResultsOut of the 14,407 cohort members of this study,

7,073 participants (231 black men, 2,370 white men,523 black women, and 3,949 white women) wereavailable for analysis not involving serum or dietarydata after exclusions (Figure 1). Because of therelatively small number of black participants in-volved, some of the results, especially for black men,are based on small numbers; therefore, the findingsshould be interpreted with caution.

The distribution of categorical variables and meanswith standard errors of continuous variables at base-line for the four race and sex groups are presented inTables 1 and 2, respectively. The four groups arecharacterized by differences in race or sex or bothrace and sex distributions of all study variables.

The 10-year incidence of hypertension increasedwith age and body mass index in all four groups anddecreased with increasing education in all groupsexcept black men (Table 3). Except among whitewomen, the incidence of hypertension was higher

among the least active group during leisure time thanamong more active participants. The incidence ofhypertension varied little across serum magnesiumand alcohol consumption levels.

Mean systolic blood pressure was 123.0 mm Hg atbaseline and 125.1 mm Hg at follow-up. The changein systolic blood pressure ranged from a decrease of65 mm Hg to an increase of 91 mm Hg. Mean dia-stolic blood pressure was 78.5 mm Hg at baseline and76.0 mm Hg at follow-up. The change in diastolicblood pressure ranged from a decrease of 61 mm Hgto an increase of 68 mm Hg.

The univariate relations were examined simultane-ously by multiple logistic regression analysis (Table4). Increasing body mass index was the only variablethat was consistently associated with the develop-ment of hypertension in all groups. In models wherewe categorized body mass index, the odds ratios formen with a body mass index of 27.3 or greater andwomen with a body mass index of 27.8 kg/nr orgreater compared with those who had a smaller bodymass index were 2.78 for black men (p=0.0032), 1.64

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Ford and Cooper Risk Factors for Hypertension 601

TABLE 2. Means and Standard Deviations of Continuous Variables at Baseline: NHANES I-Epldemiologic FoUownp Study, 1971-1984

Variable

Cholesterol level (mg/dl)Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)Resting heart rate (beats/min)Dietary intakeCalcium (mg/day)Potassium (mg/day)Sodium (mg/day)Calories (NoVday)Serum cation levels (meq/1)

CalciumPotassiumSodiumMagnesium

Black men(»=231)

215.8±49.0126.9±13.181.4±8.374.5±12.1(#i=119)

704.8±482.22,074.9±l,281.72,424.7± 1,504.82,227.8±931.9

9.8±0.54.1±0.3

142.4±2.81.6±0.2

White men(n=2,370)

215.4±43.2125.8±13.080.6+8.077.0±11.9(n = 1349)

938.7+660.12,674.6± 1,267.42,770.8 ±1,637.62,426.6 ±998.6

9.7±0.44.1±0.3

142.7±3.41.7±0.1

Black women(n=523)

209.1 ±44.9122.2±14.679.2±8.879.6±11.4(n=285)

464.5±382.2l,439.1±851.01,570.1 ±1,033.51,523.1 ±780.6

9.6±1.04.1 ±0.3

141.4±3.61.6±0.2

White women(n=3,949)

213.7±47.7121.2±14.977.0±9.080.9±12.2(n=2,418)

657.2±463.1l,924.7±902.51,835.7± 1,088.01,582.5±637.4

9.6±0.44.0 ±03

142.2±3.11.7±0.1

PRace

0.07300.15990.00010.0030

0.00010.00010.00010.0001

0.47910.65810.25800.0001

Value

Sex

0.05780.00010.00010.0001

<0.00010.0381

<0.0001<0.0001

0.00010.00010.00290.0001

for white men (p<0.0001), 1.84 for black women0=0.0020), and 2.16 for white women (/><0.0001)(data not shown). Education was inversely related tothe probability of hypertension developing amongwhite women and was of borderline significanceamong white men and black women. Serum magne-sium levels were inversely related to the incidence ofhypertension. White men who consumed 3 or moredrinks/day were at increased risk for hypertensiondeveloping compared with white men who drank 1-2drinks/day (odds ratio 1.55, 95% confidence limits1.04-2.32). The regression coefficients for alcoholuse among black men suggested a similar associationbut were not statistically significant. This is in con-trast to white women, who had a lower risk ofhypertension if they consumed less than 1 drink/day.Physical activity did not predict the development ofhypertension.

For the dietary analysis, 4,772 white subjects freefrom hypertension at baseline and with completedata for the dependent and independent variableswere available for analysis (Table 5). Because ofsmall numbers, the analyses were restricted to whiteparticipants. Among white men (n = 1,709), no signif-icant findings were observed in statistical models thatadjusted for age or age and caloric intake. Amongwhite women (n=3,063), calcium, potassium, andsodium intake were all inversely related to hyperten-sion in statistical models that adjusted for age only.However, in models that adjusted for age and caloricintake, no significant results were found. Body massindex appears to confound the relation betweencalcium and potassium intake and hypertension butnot that of sodium intake.

There was no evidence that baseline serum levelsof calcium, potassium, or sodium were predictive ofthe future risk of hypertension in either univariate ormultivariate analysis (Table 6).

DiscussionRelatively few epidemiological investigations have

prospectively examined potential causes of hyperten-sion. We examined the relation of a number ofvariables to hypertension development after a meanfollow-up period of 10 years. Education and bodymass index were the two variables that most consis-tently predicted the incidence of hypertension acrossall four race and sex groups.

A hypertension threshold of 160 mm Hg or morefor SBP or 95 mm Hg or more for DBP was chosenfor two reasons. First, during the period of this study,the prevailing definition of hypertension was basedon this threshold. Only in 1984 was the definitionchanged to a SBP of 140 mm Hg or more or a DBP of90 mm Hg or more.1 Second, only one blood pressuremeasurement was obtained at baseline. Conse-quently, the possibility of misclassifying a participantas hypertensive is greater at the lower threshold ofhypertension.

Various anthropometric measures have been asso-ciated with blood pressure.11 Our study demonstratesthat, independent of age, body mass index was a riskfactor for hypertension. Data from the NHANES IIstudy showed that the prevalence of obesity (com-bined overweight and severe overweight categories)was 32.2% among white men, 35.9% among blackmen, 34.9% among white women, and 63.1% amongblack women.10 If the odds ratios for obesity previ-ously calculated are assumed to be approximations ofthe relative risk, then the population attributable riskis 12.6% for white men, 23.0% for black men, 18.7%for white women, and 28.8% for black women. Thesedata underscore the importance of weight control inthe prevention of hypertension, especially amongblack men and women.

Several studies have shown that socioeconomicstatus is inversely related to blood pressure.12-13 Ourresults also show that participants with more ad-

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

602 Hypertension Vol 18, No 5 November 1991

TABLE 3. Ten-Year Incidence of Hypertension,

Variable

Age (yr)25-4445-64£65

Income<$ 10,000$10,000-14,999$15,000-19,999$20,000-24,9992:$25,000

Education (yr)<12

12

212

Nonleisure-time physical activityVery activeModerately activeInactive

Leisure-time physical activityMuch exerciseModerate exerciseLittle or no exercise

WeightNormal weightObeseSevere obesity

Alcohol use (drinks/day)<1

1-2

£ 3

Magnesium level (meq/1)sl.59> 1.59-1.68> 1.68-1.77>1.77

n

27

37

17

58

7

7

6

3

54

15

12

45

33

3

16

18

47

51

18

12

67

8

6

29

16

2214

Black

,NHANES

men(n = 231)

%

26.244.138.7

36.916.3

43.8

60.0

60.0

40.6

26.3

293

34.4

36.4

33.3

32.0

23.1

45.6

29.3

51.4

54.6

35.8

30.8

33.3

32.2

37.2

43.1

29.8

p Value

0.034

0.021

0.116

0.952

0.006

0.006

0.868

0.486

I-Epldemlologlc Followup

n

156

216

106

215

138

62

27

36

195

159

124

240

201

37

122

190

166

340

97

41

352

63

63

86

120

135

137

White men(n=2,370)

%

13.3

26.7

27.3

21.1

20.4

18.3

15.6

22.2

24.3

20.0

16.1

20.3

20.3

18.8

18.3

19.3

23.2

18.2

26.5

31.3

20.3

16.9

23.6

21.2

20.4

20.5

19.1

p Value

<0.001

0.415

<0.001

0.878

0.046

< 0.001

0.111

0.836

Study,

n

130

36

25

157

21

82

3

113

62

16

82

81

28

17

39

135

95

59

37

173

10

8

70

53

40

28

1971-15*84

Black women(n=523)

%

33.9

37.5

56.8

38.2

32.8

24.2

22.2

50.0

41.9

35.8

20.0

33.7

35.8

51.9

34.7

27.5

40.7

29.9

46.1

48.1

36.4

35.7

40.0

32.7

41.1

37.4

38.4

p Value

0.011

0.368

0.042

0.042

0.023

<0.001

0.944

0.451

n

337

297

180

468

178

8844

36

354

317

143

355

395

64

130

320

364

532

191

91

731

66

17

193

213

214

194

White women(n=3,949)

%

13.4

29.8

40.7

25.2

16.8

15.9

17.1

16.2

29.6

18.0

14.5

19.3

21.6

23.3

19.7

19.4

22.2

17.0

33.1

38.9

20.4

23.4

21.5

19.3

19.9

21.6

21.8

p Value

<0.001

<0.001

< 0.001

0.115

0.128

<0.001

0.470

0.426

vanced education were less likely to become hyper-tensive than were participants with fewer years ofeducation. Income was not a particularly good pre-dictor of hypertension.

Two studies have demonstrated an inverse associ-ation between the incidence of hypertension andphysical activity or fitness.14-15 Among 6,039 men andwomen aged 20-65 years, those with low levels offitness had a relative risk of 1.52 for developinghypertension (defined either as ever being told by aphysician that they had hypertension or as the use ofantihypertensive medications).14 A lack of strenuousexercise was a risk factor for physician-diagnosedhypertension developing among 14,998 male Harvardalumni.15 Our present findings could not confirm theresults of these studies.

The relation between sodium use and blood pressurehas been much studied and continues to remain con-troversial.16.17 The INTERSALT study, a large cross-sectional study, has shown that a reduction in sodiumintake of 100 mmol/day would lead to a mean reductionof 2.2 mm Hg in SBP and 0.1 mm Hg in DBP.18 Ouranalysis of data from the NHANES I EpidemiologicFollowup Study shows no evidence that sodium con-sumption was related to the incidence of hypertensionin a large sample of the US population. In this regard,our study joins other within-population studies thathave failed to confirm a positive relation betweensodium consumption and blood pressure.

Also, the data from this study did not show areduction in the risk of the incidence of hypertensionwith increased use of dietary potassium at baseline.

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Ford and Cooper Risk Factors for Hypertension 603

TABLE 3. Continued

Variable

Calories (No./day)

s i , 230.85

> 1,230.85-1,671.09

>l,671.09-2,252.66

>2,252.66

Dietary calcium intake(mg/day)

£343.75

>343.75-591.11

>591.11-953.77

> 953.77

Dietary sodium intake (mg/day)

£1,161.8

>1,161.8-1,782.12

> 1,782.12-2,671.93

>2,671.93

Dietary potassium intake(mg/day)

£1,336.34

> 1336.34-1,919.28

> 1,919.28-2,633.59

> 2,633.59

Serum calcium level (mg/dl)

£9.4

>9.4-9.7

>9.7-9.9

>9.9

Serum potassium level (meq/l)

£3.9

>3.9-4.1

>4.1-43

>4.3

Serum sodium level (meq/l)

£141

>141-143

>143-144

>144

n

8

12

21

23

20

17

18

9

13

16

20

15

27

12

14

11

7

10

7

8

5

3

2

7

5

5

4

3

Black men(n=231)

%

33.3

41.4

41.2

29.1

41.7

37.8

32.1

26.5

35.1

43.2

35.7

28.3

39.1

36.4

36.8

25.6

25.9

52.6

31.8

24.2

333

333

18.2

58.3

38.5

29.4

40.0

37.5

p Value

0.456

0.497

0.539

0.517

0.164

0.234

0.934

n

33

50

109

168

47

78

104

131

41

68

%

155

28

93

102

137

78

83

66

44

31

31

32

23

31

41

24

22

White men(n =2370)

%

25.4

18.7

23.9

19.7

21.9

20.4

23.2

19.8

21.4

22.4

20.0

21.2

16.5

26.9

21.8

18.9

24.1

21.0

18.5

17.7

17.0

18.2

20.5

19.7

16.9

21.7

20.9

12.7

p Value

0.139

0.563

0.878

0.009

0.198

0.694

0.121

n

83

46

25

17

94

35

31

11

78

53

25

15

102

34

18

17

19

10

17

11

9

2

2

7

4

11

2

3

Black women(*=523)

% p

43.2

37.4

28.4

32.1

41.8

29.2

41.9

29.7

40.0

39.9

32.1

30.0

39.7

33.3

33.3

39.5

35.2

26.3

44.7

35.5

36.0

11.8

22.2

43.8

16.7

40.7

22.2

42.9

i Value

0.091

0.076

0.388

0.624

0.420

0.184

0.227

n

255

212

122

56

186

183

172

104

232

197

139

77

202

189

157

97

129

101

76

38

61

40

34

33

56

61

19

33

White women(n=3,949)

%

25.3

22.7

16.1

153

213

22.7

22.2

16.8

25.0

22.4

18.8

14.9

23.6

21.7

19.8

18.0

22.3

20.6

19.4

19.2

17.5

19.6

19.3

21.6

19.2

20.5

143

203

p Value

<0.001

0.034

<0.001

0.061

0.658

0.744

0.475

Although we did note an inverse relation betweenthe two variables among white women in univariateanalysis, this relation no longer persisted in multi-variate analysis. Previous NHANES I study analysesdemonstrated a cross-sectional association betweendietary potassium intake and blood pressure.19'20

Other cross-sectional and experimental studies havealso shown an inverse relation.18-21

The association between dietary calcium intakeand blood pressure and the potential benefit oftreating hypertension with increased dietary intakeof calcium remain controversial.162223 Previousanalyses of the NHANES I and II data have yieldedconflicting findings regarding the influence of vari-ous dietary variables on blood pressure, particularly

calcium.192024-25 Other cross-sectional studies haveshown relations between dietary calcium intake andblood pressure.2026"35 Data from the Western Elec-tric Heart Study36 showed that calcium intake wasinversely related to the incidence of elevated DBP(95 mm Hg or greater) but not of elevated SBP (160mm Hg or greater). A recent report of a largecohort study of women showed that dietary calciumintake was inversely related to hypertension amongwomen.37

Although alcohol use was shown to be related toblood pressure in previous cross-sectional analyses ofNHANES I data,20-24 we found conflicting evidenceregarding the role of alcohol consumption in the inci-dence of hypertension. Among white men, and perhaps

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

604 Hypertension Vol 18, No 5 November 1991

TABLE 4.

Variable

Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis Results: NHANES

White

Pmen (n=2,370)

SE p Value

Black

P

I-Epidemiologk

men (n=231)

SE p Value

Follownp Study,

White women

P SE

1971-1984

(/i =3,949)

p Value

Black

Pwomen

SE

(*=523)

p Value

Age(yr)

Household income ($1,000s)

Education (yr)

Resting heart rate (beats/min)

Cholesterol level (mg/dl)

Body mass index (kg/m2)

Alcohol use (drinks/day)(Reference=l-2)

<1

2:3

Leisure-time physical activity(Reference=most active)

Moderate

Sedentary

Nonleisure-time physical activity(Reference=most active)

Moderate

Sedentary

Magnesium level (meq/1)

0.0256 0.0041 <0.0001

0.0116 0.0077 0.1326

-0.0348 0.0181 0.0551

0.0100 0.0044 0.0243

0.0023 0.0012 0.0653

0.0639 0.0142 <0.0001

0.0165 0.0118 0.15%

0.0510 0.0269 0.0577

-0.0583 0.0456 0.2010

0.0211 0.0124 0.0896

-0.0008 0.0032 0.8055

0.0746 0.0367 0.0420

0.1617 0.1554 0.2983 0.2478 0.4824 0.6075

0.4375 0.2054 0.0332 0.5036 0.7136 0.4803

-0.0123 0.1385 0.9292 -0.6408 0.4460 0.1508

0.1564 0.1436 0.2761 0.3958 0.3909 0.3113

-0.0758 0.1168 0.5166 0.0916 0.3221 0.7761

-0.1647 0.2100 0.4327 -0.4324 0.7999 0.5888

-0.7485 0.4129 0.0698 0.6969 0.9402 0.4585

0.0405 0.0035 < 0.0001

-0.0006 0.0064 0.9210

-0.0704 0.0162 <0.0001

0.0046 0.0034 0.1843

0.0005 0.0010 0.5788

0.0768 0.0088 <0.0001

-0.3530 0.1566 0.0242

-0.2739 0.3237 0.3975

-0.1117 0.1270 03793

-0.1249 0.1285 03313

0.0167 0.0908 0.8542

-0.0638 0.1702 0.7076

-0.2684 0.3192 0.4005

0.0112 0.0095 0.2384

0.0122 0.0194 0.5312

-0.0686 0.0389 0.0775

0.0025 0.0085 0.7635

0.0030 0.0024 0.2082

0.0588 0.0174 0.0007

-0.0478 0.4258 0.9106

0.3861 0.6366 05442

-0.4490 0.3812 0.2390

-0.0088 0.3449 0.9797

0.0812 0.2073 0.6952

05142 0.3262 0.1149

0.4121 0.6462 0.5236

SE, standard error.

among black men as well, the risk of hypertensiondeveloping was highest among those who drank anaverage of 3 or more drinks/day compared with thosewho drank 1-2 drinks each day. However, among whitewomen, a lower risk of hypertension was found amongthose who did not drink at all (odds ratio 0.70, 95%confidence limits 0.52-0.95) or who drank less than 1drink/day compared to women who had 1-2 drinks/day.

This agrees with findings from a large cohort study ofwomen.38 However, unlike that study, we could notdemonstrate a relation between an increased risk ofhypertension and increased alcohol consumption.

Several study limitations must be considered in theinterpretation of our findings. First, blood pressure wasdetermined by a single measurement taken at thebaseline examination. In most studies, three measure-

TABLE 5. Logistic Regression Analysis* Results Relating Dietary Cations to Hypertension: NHANES I-Epldemiologic Followup Study,1971-1984

Variable

Continuous levels

Calcium (per 100 meq/1)

Potassium (per 100 meq/1)

Sodium (per 100 meq/1)

Quartilesf:

Calcium intake

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4

Potassium intake

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4

Sodium intake

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4

White

P

0.0076

0.0035

0.0057

-0.0937

0.0845

-0.0398

0.6272

03858

0.2758

0.0584

0.0153

0.1589

men (n = 1,709)

SE

0.0109

0.0066

0.0046

0.2120

0.2057

0.2113

0.2438

0.2428

0.2549

0.2273

0.2176

0.2225

p Value

0.4859

05892

0.2176

0.6587

0.6811

0.8505

0.0101

0.1121

0.2792

0.7972

0.9439

0.4750

Black

P

-0.0681

-0.0302

-0.0271

-0.3787

-0.6153

-1.0549

-03428

-0.2391

-0.7632

0.2508

0.0860

-0.2872

men (n

SE

0.0463

0.0186

0.0170

0.4494

0.4605

0.6020

0.4728

0.4691

05341

05084

0.4829

05824

= 183)

p Value

0.1415

0.1053

0.1122

0.3994

0.1815

0.0797

0.4684

0.6104

0.1530

0.6218

0.8587

0.6219

White women (n =3,063)

P

-0.0019

-0.0029

-0.0062

0.1085

0.1528

0.0085

-0.1387

-0.1052

-0.0676

-0.1074

-0.1793

-0.3188

SE

0.0128

0.0069

0.0058

0.1259

0.1326

0.1590

0.1243

0.1362

0.1702

0.1201

0.1369

0.1741

p Value

0.8834

0.6740

0.2838

0.3886

0.2491

0.9573

0.2645

0.4399

0.6912

0.3712

0.1903

0.0671

Black women (r

P

-0.0098

0.0100

-0.0030

-0.5001

0.1082

-0.2608

-0.1441

-0.1029

0.4961

0.1037

-0.1934

0.0424

SE

0.0359

0.0155

0.0134

0.2585

0.3006

0.4365

0.2654

03463

0.4151

0.2443

03109

0.4077

1=456)

p Value

0.7842

0.5181

0.8258

0.0530

0.7189

05501

05873

0.7663

0.2320

0.6712

05339

0.9172

SE, standard error.•Covariates in each model includetFor quartile cutpoints, see Table

age and caloric intake.3.

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Ford and Cooper Risk Factors for Hypertension 605

TABLE 6. Multiple LogisticFollowup Study, 1971-1984*

Variable

Regression

P

Analysis Results Relating

White men (n=610)

SE

Serum Cation

p Value

Levels to Hypertension

White

P

: NHANES I-Epidemiologic

women (n=828)

SE p Value

Model 1: ContinuousCalcium (mg/dl)Potassium (meq/1)Sodium (meq/1)Model 2: QuartilesCalcium

Quartile 2Quartile 3Quartile 4

PotassiumQuartile 2Quartile 3Quartile 4

SodiumQuartile 2Quartile 3Quartile 4

-0.0607-0.1863-0.0026

0.1319-0.0773-0.1886

-0.02770.0176

-0.3296

0.429903115

-0.3355

0.2494037390.0352

0.30100.31210.3690

03063031460.3375

0.28850.35000.3456

0.80790.61820.9405

0.66130.80430.6092

0.92800.955403288

0.13620.37340.3317

-0.2585-0.10330.0023

0.0460

0.0732

-0.4775

0.0418-0.2726-0.1390

0.1474-0.5311-0.2025

0.22840.31340.0320

0.23650.26070.3619

0.25210.26950.2835

0.23360.32370.2898

0.25770.74180.9436

0.84590.77900.1871

0.86840.31180.6238

0.52790.10090.4847

SE, standard error.•Adjusted for age, income, education, heart rate, serum cholesterol level, body mass index, alcohol use, physical activity, serum

magnesium and other cation levels, and caloric intake.

ments are taken on one or more occasions, with theaverage of the last two measurements used to providegreater stability of the data. Also, the questions askedof the augmented sample used to classify participantsas hypertensive differed somewhat. This difference mayhave resulted in some people (but probably not verymany) being misclassified as normotensive.

The measurement of several of the independentvariables poses greater concerns. Dietary data werecollected at a single 24-hour recall. With this method,the intraindividual variability exceeds the interindi-vidual variability and therefore, it may not be suffi-ciently accurate to classify persons correctly. Theimpact of measurement error using this technique onpotential associations has been discussed previous-ly.3940 We tried to minimize misclassification byperforming a quartile analysis, but the results fromthis analysis did not give strong support for any effectof intake of dietary cations (Table 5).

The classification of physical activity levels in thisdata set is unsophisticated and probably resulted insignificant misclassification. Participants were simplyasked to classify themselves, without a frame ofreference, in one of three activity categories. There-fore, each participant's belief of what constitutedbeing active or sedentary dictated an answer. Thereliability of these answers has not been tested, andthe indirect validity of these data in the NHANES Istudy is limited.41 The usefulness and limitations ofsimplified physical activity questionnaires have beendiscussed elsewhere.42-43

Finally, the relatively small numbers of black menand women reduced the power of the study to detectassociations in these groups.

In conclusion, body mass index and education weregenerally the most consistent predictors for the de-velopment of hypertension after an average of 10years of follow-up among the four race and sexgroups. These data confirm the importance of weightcontrol in the prevention of hypertension and pro-vide a clear target for intervention by both thephysician in his or her daily practice and by personsin the public health sector. No strong evidence for aneffect of dietary sodium, potassium, or calcium intakeon the incidence of hypertension was observed. How-ever, the failure of our study to support findingsrelating intake of dietary cations to the developmentof hypertension may be attributable to imprecision inthe measurement of dietary data and misclassifica-tion of hypertension status. Future longitudinal stud-ies using better quantification of dietary variablesshould address the importance of dietary intake ofcations on hypertension in the general population.

References1. Hypertension prevalence and the status of awareness, treat-

ment, and control in the United States: Final report of thesubcommittee on definition and prevalence of the 1984 jointnational committee. Hypertension 1985;7:457-468

2. Rose G: Strategy of prevention: Lessons from cardiovasculardisease. BrMedJ 1981;282:1847-1851

3. National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and operation ofthe Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States —1971-1973. DHEW publication No. (PHS) 79-1310. (Vital andHealth Statistics, series 1, number 10a). Washington, DC,National Center for Health Statistics, 1973

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and operation of theHealth and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States —1971-1973. DHEW publication No. (HRA) 77-1310. (Vital andHealth Statistics, series 1, number 10b). Washington, DC,National Center for Health Statistics, 1977

5. National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and operation ofthe HANES I Augmentation Survey of adults 25-74 years,

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

606 Hypertension Vol 18, No 5 November 1991

United States, 1974-1975. DHEW publication No. (PHS)78-1314. (Vital and Health Statistics, series 1, number 14).Washington, DC, National Center for Health Statistics, 1978

6. National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and operation ofthe NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study 1982-84.DHHS publication No. (PHS) 87-1324. (Vital and HealthStatistics, series 1, number 22). Washington, DC, NationalCenter for Health Statistics, 1987

7. Madans JH, Kleinman JC, Cox CS, Barbano HE, Feldman JJ,Cohen B, Finucane FF, Cornoni-Huntley J: 10 Years afterNHANES I: Report of initial followup, 1982-84. Public HealthRep 1986;101:465-473

8. Cornoni-Huntley J, Barbano HE, Brody JA, Cohen B, Feld-man JJ, Kleinman JC, Madans J: National Health and Nutri-tion Examination I —Epidemiologic Followup Survey. PublicHealth Rep 1983;98:245-251

9. Bordley J, Connor C, Hamilton WF, Kerr WJ, Wiggers CJ:Recommendations for human blood pressure determinationby sphygmomanometers. Circulation 1951;4:503-509

10. National Center for Health Statistics. Anthropometric refer-ence data and prevalence of overweight, United States,1976-80. DHHS publication No. (PHS) 87-1688. (Vital andHealth Statistics, series 11, no. 238). Washington, DC,National Center for Health Statistics, 1987

11. Fraser GE: Preventive cardiology. New York, Oxford Univer-sity Press, 1986, pp 127-147

12. Kraus JF, Borhani ND, Franti CE: Socioeconomic status,ethnicity and risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol1980;lll:407-414

13. Rose GA, Marmot MG: Social class and coronary heartdisease. Br Heart J 1981;45:13-25

14. Blair SN, Goodyear NN, Gibbons LW, Cooper KH: Physicalfitness and incidence of hypertension in healthy normotensivemen and women. JAMA 1984;252:487-490

15. Paffenbarger RS Jr, Wing AL, Hyde RT, Jung DL: Physicalactivity and incidence of hypertension in college alumni. Am JEpidemiol 1983;117:245-257

16. Kesteloot H: Kationen en bloeddruk. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd1985;129:630-634

17. Swales JD: Salt saga continued: Salt has only small importancein hypertension. Br Med J 1988;297:307-308

18. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group: INTERSALT: Aninternational study of electrolyte excretion and blood pres-sure: Results for 24 hour urinary sodium and potassiumexcretion. Br Med J 1988;297:319-328

19. McCarron DA, Morris C, Henry H, Stanton JL: Blood pres-sure and nutrient intake in the United States. Science 1984;224:1392-1398

20. Gruchow HW, Sobocinski KA, Barboriak JJ: Alcohol, nutrientintake, and hypertension in US adults. JAMA 1985;253:1567-1570

21. Smith WCS, Crombie IK, Tavendale RT, Gulland SK, Tun-stall-Pedoe HD: Urinary electrolyte excretion, alcohol con-sumption, and blood pressure in the Scottish heart healthstudy. BrMedJ 1988;297:329-330

22. Maxwell MH, Waks AU: Cations and hypertension: Sodium,potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Med Clin North Am1987;71:859-875

23. Langford HG: Nonpharmacologic therapy of hypertension:Commentary on diet and blood pressure. Hypertension 1989;13(suppl I):I-98-M02

24. Harlan WR, Hull AL, Schmouder RL, Landis JR, ThompsonFE, Larkin FA: Blood pressure and nutrition in adults. Am JEpidemiol 1984;120:17-28

25. Sempos C, Cooper R, Kovar MG, et al: Dietary calcium andblood pressure in National Health and Nutrition ExaminationSurveys I and II. Hypertension 1986;8:1067-1074

26. Kesteloot H, Geboers J: Calcium and blood pressure. Lancet1982;1:813-815

27. Stanton JL, Braitman LE, Riley AM Jr, Khoo CS, Smith JL:Demographic, dietary, life style, and anthropometric corre-lates of blood pressure. Hypertension 1982;4(suppl III):III-135-III-142

28. Ackley S, Barrett-Connor E, Suarez L: Dairy products, cal-cium, and blood pressure. Am J Clin Nutr 198338:457-461

29. Garcia-Palmieri MR, Costas R Jr, Cruz-Vidal M, Sorlie PD,Tillotson J, Havlik RJ: Milk consumption, calcium intake, anddecreased hypertension in Puerto Rico: Puerto Rico HeartHealth Program Study. Hypertension 1984;6:322-328

30. Nichaman M, Shekelle R, Paul O: Diet, alcohol, and bloodpressure in the Western Electric Study (abstract). Am JEpidemiol 1984;120:469-470

31. Reed D, McGee D, Yano K, Hankin J: Diet, blood pressure,and multicollinearity. Hypertension 1985;7:405-410

32. Kromhout D, Bosschieter EB, Coulander C: Potassium, cal-cium, alcohol intake and blood pressure: The Zutphen Study.Am J Clin Nutr 1985;41:1299-1304

33. Kok FJ, Vandenbrouke JP, van der Heide-Wessel C, van derHeide R: Dietary sodium, calcium, potassium, and bloodpressure. Am J Epidemiol 1986;123:1043-1048

34. Liebman M, Chopin LF, Carter E, Clark AJ, Disney GW,Hegsted M, Kenney MA, Kirmani ZA, Koonce KL, KorslundMK, Moak SW, McCoy H, Stallings SF, Wakefield T: Factorsrelated to blood pressure in a biracial adolescent femalepopulation. Hypertension 1986;8:843-850

35. Joffres MR, Reed DM, Yano K: Relationship between mag-nesium intake and other dietary factors to blood pressure: TheHonolulu Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr 1987;45:469-475

36. Zhang HY, Liu K, Shekelle R, Dyer A, Stamler J: The impactof calcium intake on incidence of elevated blood pressure: TheWestern Electric Study (abstract). Am J Epidemiol 1988;128:916-917

37. Witteman JC, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, SacksFM, Speizer FE, Rosner B, Hennekens CH: A prospectivestudy of nutritional factors and hypertension among USwomen. Circulation 1989;80:1320-1327

38. Witteman JC, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Kok FJ,Sacks FM, Speizer FE, Rosner B, Hennekens CH: Relation ofmoderate alcohol consumption and risk of systemic hyperten-sion in women. Am J Cardiol 1990;65:633-637

39. Liu K, Stamler J, Dyer A, McKeever J, McKeever P: Statisticalmethods to assess and minimize the role of intra-individualvariability in obscuring the relationship between dietary lipidsand serum cholesterol. / Chronic Dis 1978^1:399-418

40. Sempos CT, Johnson NE, Smith EL, Gilligan C: Effects ofintraindividual and interindividual variation in repeateddietary records. Am J Epidemiol 1985;121:120-130

41. Farmer ME, Locke BZ, Moscicki EK, Dannenberg AL, Lar-son DB, RadlofT LS: Physical activity and depressive symp-toms: The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am JEpidemiol 1989;128:1340-1351

42. Slater CH, Green LW, Vernon SW, Keith VM: Problems inestimating the prevalence of physical activity from nationalsurveys. Prev Med 1987;16:107-118

43. Washburn RA, Adams LL, Haile GT: Physical activity assess-ment for epidemiologic research: The utility of two simplifiedapproaches. Prev Med 1987;16:636-646

KEY WORDS • body mass index • calcium • diet • education• risk factors • magnesium • potassium • populationstudy • sodium

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

E S Ford and R S CooperRisk factors for hypertension in a national cohort study.

Print ISSN: 0194-911X. Online ISSN: 1524-4563 Copyright © 1991 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved.

is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231Hypertension doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.18.5.598

1991;18:598-606Hypertension.

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/content/18/5/598World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the

http://hyper.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/

is online at: Hypertension Information about subscribing to Subscriptions:

http://www.lww.com/reprints Information about reprints can be found online at: Reprints:

document. Permissions and Rights Question and Answer process is available in the

Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about thisOffice. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click

can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the EditorialHypertension Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published inPermissions:

by guest on May 24, 2018

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from