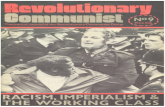

Revolutionary Communist #9 - Racism, Imperialism & the Working Class

Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

-

Upload

spin-watch -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

Transcript of Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

1/41

." =:=----::-:: -.;.--,-=-','

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

2/41

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

3/41

Editorial T heir altern ative an d o urs

'Many trade unionists seem to have accepted Mrs Thatcher'sargument that the plight of the unemployed is in largepart the result of fellow union members pricing them outof jobs.' The Economist 20 December 1980The Economist's observation that British trade unionistshad no answer to Thatcher's arguments was not an idleboast. Today, trade unions are on the defensive and arelosing the battle over redundancies and wages. To be sure,the employers' success over workers is not due solely to thecompelling arguments of the ruling class.Massredundanciesand the prospect of a deteriorating economy have placedconsiderable pressure on those still at work. As the Engin-eering Employers Federation director of operations, MrPeter Ball noted, the falling rate of pay settlements 'is areflection of realism that is being shown at domestic level,where companies are still faced with short-time working,redundancies and hard business prospects'r'

How were the arguments lost?Nor was it Margaret Thatcher on her own who won thearguments for capitalist realism. That honour also goes tothe left wing of the Labour Party and their co-thinkers inthe labour movement. The British left has no distinctivetheory of capitalism. Its response to the world reces-sion of 1974 was to draw up plans to eliminate capitalistanarchy and inequality through a progressive Labourgovernment. But this naive belief that workers' interestscould be defended by economic reforms was soon exposedby Labour's period of office, 1974-79.

The experience of the notorious SocialContract showedthat the interests of the working classand of British capital-ism were diametrically opposed. This merely confirmedMarx's proposition about the fundamental antagonism ofclassinterest between workers and capitalists. Unfortunatelythe lessons of these years have not been assimilated by theworkers' movement.Why? Because right from the beginning, in fact rightfrom the tum of the century, the Labour leadership hasaccepted the terms of the debate set out by the ruling class.Restoring profitability and regenerating British industrybecame the shared objectives of left and right alike. The lefthas no distinct objectives: it only puts forward distinctpolicies for achieving these national aims. Economic sal-vation, according to the left's Alternative Economic Strategy(AES), could be achieved through state investment, stateplanning of industry and trade, state ownership and indus-trial democracy.The main effect of the AES has been to draw workerscloser to the bourgeois state and to educate them aboutcapitalist reality. A recently published pamphlet by theLabour Coordinating Committee boasts about this achieve-ment: 'investment in the National Economic DevelopmentCouncil (NEDC) and other related bodies, coupled withattempts by the Labour governments to rejuvenate industry

in cooperation with the unions' led 'to a far higher degreeof expertise about, and knowledge of, the economy and ofparticular industries by trade unions'.2Initially supporters of the AES emphasised the 'boldsocialist potential' of this alternative. But as the capitalisteconomy fell into recession, the utopian elements of theAES were compromised. The ruthless anti-working classmeasures required for the regeneration of capitalist industrymeant the left reformists had to retreat. But the mostimportant point is that during 1974-79 the AES encouragedmilitant workers to find a solution to their problemsthrough class collaboration and persuaded them to acceptresponsibility for the state of the capitalist economy.Workers became uneasy about defending their livingstandards because this was 'unrealistic' from the point ofview of industry. Once the left reformists had educatedtrade union militants, it only remained for Thatcher tocomplete the process.

An alternative business strategyDuring the past two years British capitalism has declinedfurther still. Those who take responsibility for the state ofBritish industry in the labour movement have been forcedto lower their sights, and in practice most of the socialistrhetoric of the AES has been abandoned. The aim of theleft reformists is to save what's left rather than promisegrand reforms. A leading article in a recent issue of Tribune,the paper of the Labour left, warned:'There are no immediate economic miracles for capitalism andthere will be no immediate economic miracles for socialism either.'Even if the most radical elements of the alternative economicstrategy were put into operation by a future Laboun.govemmentwithin the first few months of achieving office, the results wouldtake two or three years to have any effect.'The need for re-investment in industry is so great and thedamage which the Tories have done to the economy is so enormousthat, apart from the redistribution of wealth between the rich andthe poor, there would be little or no room for much increase in ourgeneral living standards.,3The need for investment and the criterion of profitabilityoverride the interests of workers. It never occurs to theseleft economists that the condition for more investments ismore unemployment, more attacks on working conditionsand lower pay. That the restoration of profitability requiresenormous sacrifices from workers is dishonestly passedover. Instead labour bureaucrats fall over themselves todemand more investment and state subsidies.The TUC's Plan for growth: the economic alternativeexemplifies this approach. This 'alternative' consists ofdemanding that the state invests 6.2 billion over twoyears. Others have modified versions of this investmentplan. Recently the engineering union's white-collar section,AUEW-TASS, published a pamphlet on GKN. Noting that25000 jobs have been lost since 1976 at GKN, it proc-eeded to ignore the question of fighting redundanciesaltogether. Instead it argued that GKN must stop investingcapital abroad. According to TASS, investing in Britain is

1

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

4/41

good business and is incidentally good for jobs:'GKN should, for example, base its automotive sector here inthe UK instead of investing heavily in Europe and the USA. Itsvirtual monopoly on constant velocity joints gives it an importantadvantage which would aid ~ur UK export performance and providemuch needed employment.'During the past year trade union bureaucrats have becomeinvestment specialists. In the nationalised industries unionleaders have united with employers to demand more invest-ment. Railway leaders have even threatened strike actionunless more investment was forthcoming. In engineering,the AUEW has taken to articulating the demands of thebosses - lower interest rates, a weaker pound and lowerenergy prices for the engineering industry.

It is not surprising that with this wholesale acceptanceof capitalist economics by both the left and the right wingof the labour movement the capitalist class has taken theinitiative.

Preparing for powerThe present capitalist crisis will not be resolved in thesphere of economic policy. There are no technical solutionsto the crisis of imperialism. The stabilisation of capitalistrule requires the defeat of the working class. And that's justthe beginning. It will be the outcome of imperialist rivalrieswhich will determine who invests where and which capital-ists will enjoy the fruits of a restructured system. But onething is clear: the losers will be the working class.

The article 'World in recession' in this issue of Revol-utionary Communist Papers outlines the main trends in theworld economy today. The Marxist analysis of the crisisshows that the issue is not one of economics but of power.Class power will determine whether it is the realism of thebourgeoisie or the interests of the workers which willprevail. It follows that the job of Marxist theory is tostrengthen the anti-capitalist potential of the labour move-ment, both to give it a wider focus and to expose thereactionary character of reformist 'alternatives'. Theorymust be brought to bear on the day to day struggles so as tobring about the emergence of a distinct proletarian alter-native. Workers will of course go on fighting regardless ofthis ideological struggle. But they will fight for more invest-ments, import controls and, ultimately, fight the imperialistwar for the bosses.

This journal is sponsoring 'Preparing for power', aninternational conference on the working classmovement inthe 'eighties. The conference will work towards identifyingthe political obstacles to building an independent prolet-arian movement. It will outline the key ideological issuesthat arise on the shop floor and the wider problems thatface the working class as a whole. Shop-floor activists aswell as speakers from overseas will examine the experienceof the international labour movement over the past decade.We welcome the participation of readers of RevolutionaryCommunist Papers at this conference.

Frank RichardsJuly 1981

1 The Times, 11 May 1981.2 Labour Coordinating Committee, Trade unions and socialism,1981, p12.3 Tribune, 24 April 1981.4 AUEW-TASS, GKN: a caseof British industry at risk, 1981, p8.

Dates: 11-13 SeptemberVenue: University of London Union,Malet Street, London We1Registration: 6.00 (3.00 unemployed)At a time when the British left is in disarray, active workersneed to get down to considering the major problems thrownup by the deepest capitalist recession in fifty years. This iswhat the next step conference on the working class move-ment in the 'eighties aims to do.When there is so much at stake understanding what isgoing on in the labour movement is crucial. The traditionalreformist parties of the working class are in crisis. Yet thereisno convincing political alternative to the social-clemocraticand communist parties.Preparing for power will address the major theoreticaland practical questions facing active workers. A wide rangeof workshops will examine such important issues as thenature of reformism, the transformation of the labourmovement in the post-war period and the impact of therecession on the working class. Other workshops will drawtogether the recent experiences of active trade unionists intheir fight against redundancies. Come along and participatein these important discussions and debates.Three days of workshops, discussion and debate The tasks of the Revolutionary Communist Party in the'eighties Workers' struggles - Britain, France, Germany, Italy,Eastern Europe ... What's going on in the unions. Fighting redundancies.The problem of sectionalism. Occupations: the recentexperience Social democracy and the working class. The Labour leftand the unions. The Left Alternative Strategy Stalinism, past and present. What happened to Euro-communism? Fighting the divisions in our ranks. Racism and theunions. The position of women workers. Is there an aristoc-racy of labour?For registration write to BM RCT, London WC1N 3XXCheques and postal orders payable to RCT AssociationEnquiries: phone 01-274 3951

2

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

5/41

WORLD IN RECESSION1. THE THEORY OF BREAKDOWN

The beginning of the 'eighties sees world capitalism slideinto its second general recession since 1945. The years offaltering recovery since 1974-75 are over; already weak, thesystem takes one more step into ruin. But why is there arecession?Recessions can take different forms - too many goodschasing too few buyers, the under-utilisation of capacity ora series of bank crashes, for example. But the basic forcebehind them is the crisis of profitability. As the systemgrows and capital accumulates, the rate of profit on capitalinvested tends to fall. To survive, capitalists are forced toraise their productivity and cheapen the commodities theyproduce. Now, this process increases the rate of surplus-value, because each worker makes more profit for his em-ployer than before. But because productivity rises arebrought about by the mechanisation of the labour process,the extra profits created have to be measured over a stilllarger increase in the value of means of production. In otherwords, because productivity rises lead to the displacementof workers - the only source ofsurplus-value - bymachines,the mass of profits declines in relation to the total capitaloutlaid.This tendency for the rate of profit to fall has animportant consequence. At a certain stage of the accum-ulation process the amount of profits available is notsufficient to fund investment of the scale required to con-tinue production. A crisis sets in.The capitalist crisis arises directly out of the contra-dictions inherent in the system of capitalist production. Itis not the result of natural causes, 'wage militancy' or mis-guided policies on the part of the ruling class. Over the pastdecade bourgeois economists in all the major capitalistcountries have noted a trend for profit rates to fall. Theyhave also noted the underlying cause of this - the sub-stitution of machinery for workers. As The Economistpointed out two years ago: 'over the past 20 years or sothere has been a steady shift from labour to capital in theratio of industrial Inputs'."Marx called the tendency of the rate of profit to fallthe most important law of the capitalist economy. How-ever, to explain the crisis capitalism faces today we mustestablish how this law works itself out in practice. Marx'sanalysis itself allows us to do this. It not only enables usto understand the root cause of capitalist breakdown; italso enables us to assessvital features of the world economytoday - the cyclical growth of capitalist production, theuneven impact of the crisisin different countries and so on.In the following paragraphs we set out the basic toolsneeded to make such an assessment.

Holding off the final reckoning

In Capital, Marx sets out a number of factors which canimpede or even temporarily reverse the fall in the rate ofprofit.2 The bourgeoisie can increase its profits at the

expense of workers by extending the workin} day, inten-sifying work, employing women and children and drivingdown wages below the value of labour-power. These meth-ods boost the rate of profit because they increase theproduction of surplus-value without increasing investmentin the means of production to the same degree. The present-day attacks on the living standards and working conditionsof the proletariat show how the capitalists are trying tobring these counter-crisis measures into effect.Another factor which slows the fall in the rate ofprofit is the cheapening of the elements of constant capital.This happens when productivity increases reduce the valueof the machinery and raw materials capitalists have tobuy." This factor has, however, only a short-term effect.What Marx called the organic composition of capital willstill tend to rise (and thus prompt a fall in profitability),because the capitalists are forced to deploy an ever greatermass of constant capital.fProducing cheap and/or synthetic raw materials andreducing the price of energy is one method of cutting thecost of constant capital. It is an important method becauseas productivity increases the value of raw materials comes

1 The Economist, 25 August 1979, p61.2 K Marx, Capital, Vol 3, Lawrence & Wishart (L&W), 1974,chapter 14 (all references to Capital are to this edition). Herewe only consider the counteracting influences most relevant totoday's crisis. In the next sections we show their current role.3 This enables the capitalist to spread the costs of reproducinglabour-power over the whole family. The level of the extrawages paid rises proportionately less than the extra work done.Between 1959 and 1978 the proportion of women employedin the workforce in Britain rose from 33 per cent to 41 percent. Similar trends are evident for other countries too (LloydsBank Review, January 1980). The employers are also able toemploy women under more exploitative conditions, with lowerpay, fewer benefits, more short-time employment, etc.4 In a period of crisis, the elements of constant capital can alsobecome depreciated as companies go bankrupt and their assetsare sold at knock-down prices. Ifmachinery, raw materials orplant retains its use-value, this will be of benefit to the capital-ists buying. The Financial Times noted that: 'Thousands oftonnes of second-hand factory machinery are being soldweekly at auctions and through private sales as a result offactory closures in Britain ' (27 December 1980). Purchasers ofthese depreciated capital goods included capitalists from SouthAfrica, Israel, West Germany, France and Italy. One dealeralone sold an average of 300 tonnes of machinery a week over-seas. Total exports are estimated at several thousand tonnesa week.

5 K Marx, T he ori es o f s ur plu s- va lu e , Part 3, L&W,1972, pp366-67.

3

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

6/41

to make up a growing proportion of the value of commod-ities and thus has a growing impact on the rate of profit.6Two more forces which can act as a counter-tendencyto the fall in the rate of profit are international trade andthe export of capital.On the side of imports, trade allows a country to ob-tain machinery, raw materials and means of subsistence at aprice lower than that at which they are produced domest-ically. This reduces the cost of the elements of constantcapital and the cost of maintaining the working class. Onthe side of exports, trade allows capitalists to overcome thebarriers of the national market. If the domestic marketslumps or does not grow fast enough, the expansion ofproduction can be maintained through exports. In addition,when an advanced capitalist country trades with a back-ward one, the higher productivity of the former can lead tofurther profits? This is one reason why, over the past 30years, the imperialist economies have increased their depen-dence on exports.8The export of capital acquires a particular significanceonce domestic profit rates begin to fall. Capitalists investabroad to secure a rate of return which is higher than thatavailable at home. Overseas investment opens up newsources of labour and markets, and allows access to rawmaterials. It also allows the capitalists to secure morefavourable conditions for production. Capital exports donot raise the rate of profit at home, but they do increasethe mass of profits available to the capitalist class and,through this, curb the tendency towards stagnation.These counter-tendencies to the fall in the rate ofprofit ensure that this fall operates as a tendency as capitalaccumulates. The rate of profit still declines, but thedecline is temporarily checked through their operation. Atthis point we must also consider another modifying in-fluence on the declining rate of profit: the role of credit incapitalist production.

Borrowing timeThrough the extension of credit capital can go on accum-ulating beyond that point at which existing levels of profit-ability would otherwise dictate a halt.9 Capitalists canborrow funds through the banks and other agencies to helpthem overcome what appear as temporary difficulties -'cash-flow problems' and the like. In this way they can keepproduction going. They can borrow money to financefurther investment and so expand output, in a situationwhen the underlying conditions of profitability do notwarrant this. They can stimulate consumer demand throughthe provision of hire purchase facilities and other forms ofcredit, and so ensure that idle production capacity isutilised. Fixed costs are then spread over a greater outputso that costs of production are reduced.Credit spurs investment, which in turn raises product-ivity. The mass of profits is thus increased and furthergrowth encouraged. Because large firms are better placed toobtain it than small ones, credit also promotes the central-isation of capital into fewer hands. This allows the biggercapitalists to consolidate their operations and so stay inbusiness.10The concept of 'finance capital' reveals the ever-increasing importance of the role of credit. Lenin explainedit as follows: 'The concentration of production; the mono-polies arising therefrom; the merging or coalescence of thebanks with industry - such is the history of the rise offinance capital and such is the content of this term'.llAlongside the accumulation of capital goes the concen-

tration and centralisation of production. But with accum-ulation; the credit and banking system develops too,becoming in turn an important factor in the growth ofindustry. As Marx explained, in its first stages the creditsystem 'furtively creeps in as the humble assistant ofaccumulation, drawing into the hands of individual orassociated capitalists, by invisible threads, the moneyresources which lie scattered over the surface of society, inlarger or smaller amounts; but it soon becomes a new andterrible weapon in the battle of competition and is finallytransformed into an enormous social mechanism for thecentralisation of capitals,.12 By accelerating the develop-ment of large-scale industry, credit becomes a major forcein the socialisation of production and the transformationof capitalism into monopoly capitalism. The term 'financecapital' therefore refers not to banks alone, but to theintegration of banking capital with industrial capital.Finance capital is an essential feature of imperialism.That banking operations are more tied up with indus-trial ones than ever before is strikingly evident today. Bigcorporations, with annual turnovers of several billiondollars and enormous financial resources, are now closelyintertwined with the credit system. Many have set upfinance arms of their own: these issue long-term bonds andorganise the borrowing of many millions of dollars.13 Inthe USA, a 'commercial paper' market has been establishedin which companies lend their surplus cash directly to othercompanies for short periods of time, thus cutting out finan-cial institutions altogether. The commercial paper out-standing at the end of 1979 totalled $115 billion. 14While industry gets into banking, the banks get intoindustry. Banks not only provide industry with giganticloans but also take an active part in the running of it.Banking and financial institutions have developed a numberof special skills with which to service industry: they noworganise mergers and takeovers, finance international tradeand lease capital equipment. It is true that, with the excep-tion of West Germany, important bank shareholdings inindustry are still rare; but recently there has emerged atrend for banks to convert long-term loans to ailing com-panies into equity stakes in them.15 Thus when an inter-national consortium of banks recently put together rescuepackages for Chrysler and Massey-Ferguson they also tookpart-ownership of the two companies.Like capitalist production, the credit system operateson an international scale. The West's idle money is central-ised through the banks and put to use as the bourgeoisiesees fit. The growth of credit on an international levelserves to bind each area of the world more tightly together.Through the international extension of credit the imper-ialists open up new markets and accelerate the pace ofcapital investment; the relations of dependence betweendebtor nations and the banks are consolidated, and thefortunes of each particular national capital have a moredirect influence on the health of the whole system.Both nationally and internationally, however, creditcan only postpone or mitigate the capitalist crisis. It cannotsolve it. By lubricating the mechanisms of accumulation,credit merely ensures that capitalism's fundamental prob-lem - lack of profitability - is exposed more forcefully, inthe form of monetary or financial crises. Bourgeois com-mentators may diagnose accelerating inflation, massivegovernment debts and the burgeoning growth of the moneysupply as capitalism's basic malaise, but these are onlysymptoms. Credit is and will remain vital to the proppingup of capitalism, but it cannot delay indefinitely themeasures required to restore the rate of profit.From all that we have said so far it should be clear thatthe path the capitalist crisis takes will not be one of unmit-

4

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

7/41

igated decline. There will be numerous variations on thedownward trend. Much depends on the course whichcapitalist competition takes. It is to this question that wenow turn.

Dog eats dog

Competition is the interaction of one capitalist with anotherin the market. Marx calls it the 'essential locomotive force'of the capitalist economy, which, however, does notestablish the laws of that economy, 'but is rather theirexecutor' .16 Competition compels each capitalist to followthe inexorable logic of the system - to cut costs, raiseproductivity or make workers redundant - just in order tosurvive. Since the industrial capitalist experiences the crisisthrough the effects of competition, it appears to him thathe can escape it if only he can remain competitive. Hisproblems seem to derive from the efforts of his rivals toincrease their share of the market, perhaps by using 'unfairpractices'. Even if he has an inkling of the general illnessgripping world capitalism his only practical course of actionis to strengthen his competitive position. Thus the objectivedictates of the system imposed on the individual capitalistare experienced as a matter of subjective choice.The capitalist believes he can win if, through a higherlevel of investment, he can raise productivity and hencealso the rate of profit earned. Despite the increase in theorganic composition of capital this entails, a level of prod-uctivity above the market average will enable him to under-cut his rivals, gain a higher market share, and thus tempor-arily secure a surplus-profit. The trouble is, however, thatcompetition will in turn force his rivals to invest too. Hisadvantage will disappear, his higher organic compositionwill become a general one and he and all his competitorswill have to face the consequences of a general decline inthe rate of profit.t 7

Though the individual capitalist's efforts to steal amarch on his rivals are ultimately self-defeating, this appar-ent avenue of escape will always seem open. Because theyresort to it capitalists soon find themselves in difficulties.First, overcapacity builds up so that production cannot berun profitably. Second, and as a result of this, a still more

6 Capital, Vol 3, pp108-9. A boom or a slump in the level ofcommodity prices (that is, the prices of minerals and agricul-tural commodities) modifies the tendency of the rate of profitto fall. Here we are talking of price fluctuations, not neces-sarily changes in value. The peculiar conditions under whichprimary commodities are produced and the generally unstablenature of capitalist growth together ensure that such pricesfluctuate sharply. Moreover, the speculation that engulfs thecommodity markets at a time of crisis will also exacerbateprice fluctuations. Between 1972 and 1974, the IMF index ofcommodity prices (1970=100) rose from 107.2 to 212.3,making the fall of manufacturing profitability in that periodparticularly steep. Over the next three years the index grew atthe same rate as OECD consumer prices, contributing to a

partial recovery (figures from IMF, International FinancialStatistics). For the more general effect and role of oil pricerises in the capitalist crisis, see 'Who's over the barrel?', thenext step, No 8, November/December 1980.7 This is because, faced with less local competition, prices ofcommodities exported into these markets can be higher thanthose in more developed economies.8 Between 1960 and 1970, the growth of industrial productionaveraged 6.1 per cent a year; that of exports, 8.7 per cent ayear (World Bank, World development report, 1980). See thenext section for the role of trade during the 'seventies.9 Capital, Vol 3, p441.10 The process of centralisation - mergers, takeovers within asingle industry and across industries - has been evident through-out the post-war period. This process assumed greater import-ance in the late 'sixties when the first manifestation of theworld crisisbecame evident. For a useful bourgeois account seeL Hannah & J A Kay, Concen tration in modern industry, Mac-millan, London. 1977.11 V I Lenin, 'Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism',Collected Works, Vol 22, p226.12 Capital, Vol 1, p587.13 For example, Lonrho International Finance NYrecently organ-ised'a multicurrency medium-term loan with a number ofbanks worth 270 million French francs (see advertisement inThe Economist, 24 January 1981). Likewise GMACOverseasFinance Corporation NY, a credit subsidiary of General Motors,issued a US$100m bond to seven international banks (see ad-

vertisement in the Financial Times,S February 1981). Wherebig corporations are sufficiently profitable, they may even actas net lenders to the money markets. Volkswagen of WestGermany, with annual world salesof DM30bn and a workforceof 240 000 in several countries, is a good example. A FinancialTimes reporter commented that such is the strength of the VWbalance sheet that 'in some respects it looks more like a bankthan a manufacturing company' (19 May 1980). VWhas loanedDM4.6bn to banks and has funded no less than 97 per cent ofits DM3.1bn investment programme from its own resources.14 The Economist, 29 November 1980.15 The Economist, 20 December 1980.16 K Marx, G ru nd ris se , Pelican, 1973, p552.17 Capital, Vol 3, pp264-5. In the second part of SWPtheoreticianChris Harman's recent meandering minimum opus on crisistheory, we find the assertion thae. 'the crisis can reduce ordestroy the pressure for the organic composition of capital torise' (International Socialism, series 2, No 11, Winter 1981,p45). As a result, 'a quite modest rise in the rate ofexploitationmay be sufficient to offset the downward tendency of the rateof profit' (ibid, p46). This is nonsense. Of course the crisiswillsee investment fa'll off and the elements of constant capitalcheapened. But competition forces every capitalist to raise hisorganic composition so as to improve productivity and surviveon the market. As for 'modest ' rises in the rate of exploitation,they are th'. exception, not the rule. In West Germany, forinstance, the proportion of investment that is 'capital deepen-ing' (that is, which involves introducing new techniques) ratherthan 'capital widening' (that is, which involves simply expan-ding production) has risen from 10 per cent in 1970 to over40 per cent in 1980 (The Economist, 8 November 1980,Survey of the West German economy, p26). In other words,the capitalists can only hang on today by putting throughmassive increases in exploitation. Harman also uses his consid-erable eclectic powers to give yet another rationale for theSWP's theory that arms spending can stave off the crisis. Usingthe latest revisionist interpretations of Marx's analysis of theformation of an average rate of profit, he derives the absurdresult that a higher organic composition of capital in the armssector will actually raise the rate of profit (ibid, p55). Again,he argues that though arms production is, because it is fundedthrough taxation on private industry, a drain on surplus-value,it does not harm the rate of profit. The capitalists, it seems,still 'possess' their surplus-value once they have handed itover(ibid p59). Brilliant! Perhaps Harman would like to tell themhow tanks and bombs - which is how their money ends up -can be converted back into productive capital. For a critique ofthe SWP's 'Permanent Arms Economy' theory, see 'Disarmingthe working class', the next step, No 6, August 1980.

5

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

8/41

intense competitive struggle begins as each capitalist strivesto pass the burden of the losses onto others.l8The pressure of competition limits the room for man-oeuvre each capitalist has in relation to his rivals. It alsoimpresses upon every capitalist the need to take measuresagainst the working class. The superiority one particularnational capital has over another can best be gauged bylooking at the scope of imperialist competition today. Webegin by a review of the period spanning from the early'sixties to the mid 'seventies.World market rivalry

Table 1 shows how different major imperialist powersexperienced different growth as the tendency towardscapitalist collapse gathered speed. Britain and the USA hadthe lowest rate of growth of output and productivity inmanufacturing industry, while Japan had the highest. WestGermany, France and Italy also had high growth rates;although West Germany's appears the lowest of the three,its started from a higher level.

Table 1 Output and productivity growth in manufacturingindustry, 196073 lper cent per year)

Output ProductivityUK 3.0 3.6USA 4.9 3.4Canada 5.9 4.0Japan 12.0 8.8West Germany 5.3 5.0France 5.9 5.6Italy 6.1 5.2Source: Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, March 1979

Uneven rates of growth have had two consequences: achange in the relative economic weight of each country inthe world economy and a change in its share of internationaltrade. Table 2 shows that the importance British andAmerican industry had for the West declined markedlybetween 1963 and 1975. Though the USA remains by farthe largest producer, Japan and West Germany began tochallenge it in this role. Moreover by 1975, the industrialoutput of the EEC exceeded that of the USA.

Table 2 Shares of OECO industrial production, 196375Iper centl

1963 1970 1975UK 7.4 6.4 5.6USA 44.4 43.3 34.9Canada 3.0 3.6 3.7Japan 5.3 11.9 15.5West Germany 8.5 13.2 13.5France 5.0 6.0 7.9Italy 3.5 4.4 4.9Source: National Institute Economic Review, taken from relativeweights in DECO industrial production

Table 3 shows how divergent rates of productivitygrowth and hence international competitiveness resulted ina redistribution in shares of world trade. The shares of

Britain and the USA declined while those of Japan andWest Germany rose. In 1973, West Germany's share inmanufacturing exports topped America's.

Table 3 Shares of world exports of manufactures, 196073[per centl

1960 1965 1973UK 16.5 13.9 9.3USA 21.6 20.3 16.2Japan 6.9 9.4 12.6West Germany 19.3 19.1 21.9France 9.6 8.8 9.6Italy 5.1 6.7 6.6Source: National Institute Economic Review

Underlying these developments were differential ratesof profitability. Those countries which enjoyed higher ratesof profit could sustain a higher rate of growth; though allexperienced a fall in the rate of profit, those able to gain acompetitive advantage on their rivals suffered least.Britain had one of the lowest levels of profitability onaverage, while Japan and West Germany stayed ahead.

Table 4 Rates of profit for industrial and commercial companiesin the main imperialist countries, 1960-75

1960 1965 1970 1973 1975UK 14.2 11.8 8.7 7.2 3.5USA 9.9 13.7 8.1 8.6 6.9Japan 19.7 15.3 22.7 14.7 9.5West Germany* 23.4 16.5 15.6 12.1 9.1France 11.9 9.9 11.1 10.2 4.1Italy* 11.0 7.9 8.6 4.5 0.8Source: A Glyn & J Harrison, The British economic disaster, Pluto,1980*Note: not strictly comparable to other figures

The rate of profit is closely related to the rate ofinvestment: higher profits allow more investment to befinanced, and increased investment can raise profits byimproving competitiveness. Table 5 shows how the patternof rates of investment in the imperialist world mirroredthat of profitability: Britain and the USA's performanceswere sluggish, while those of Japan and West Germanywere good.

Table 5 Gross domestic investment as proportion of GOP in themajor imperialist countries [per centl

1960 1977UKUSAJapanWest GermanyFranceItaly

191834272424

191832222421

Source: World Bank, World Development Report, 1979

6

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

9/41

How the state props up the systemThe bourgeois state represents the general interest of thecapitalist class and enforces this interest in the realm ofproduction.i" In the epoch of imperialism the interven-tionist role of the state increases and comes to play adecisive role in maintaining the conditions necessary forcapital accumulation. State intervention in industry -subsidies for ailing firms, the restructuring of particularsectors, nationalisation, credit for export - is a directresponse to the obstacles that capital encounters in theaccumulation process. The form and objectives of stateintervention depend on the particular phase of accum-ulation. However, at a time of crisis, the state assumes amore direct role in the economy than ever before. Threeimportant spheres of state intervention can be distinguished:support for industry, coercion of the working class andthe defence of the national bourgeoisie against its imperial-ist rivals.Support for industry was widespread before the onsetof the crisis. However, over the past decade or so more andmore industries have become dependent on state support.20In Britain, one of the weakest imperialist powers, fourmajor industries were partly or wholly nationalised: steel(through the founding of the British Steel Corporation,1968), cars (British Leyland, 1975), shipbuilding (BritishShipbuilders, 1977) and aeroplanes (British Aerospace,1977). Internationally, too, extensive rationalisations andinvestment in new capacity have taken place under theguiding hand of the state. The state has also been active inencouraging the establishment of new industries. In everyimperialist country today, the state has embarked on aprogramme of investment in the electronics industry.The coercion of the working class is made necessarybecause the capitalist crisis generates social upheaval.Millions of workers are made redundant and those at workare exploited still further; so the state is compelled to stepin and discipline the working class. The judiciary, policeand the army are directed to smash workers' resistance.Every effort is made to weaken the working class organ-isationally and ideologically.

The defence of the national bourgeoisie against itsimperialist rivals becomes an urgent task for the state too;but it is the pressure of world competition that determineshow the state will move. In the early stages of the crisis thestate concentrates on refining trade policy - boostingexports of commodities while erecting barriers to imports.However, as the competitive struggle intensifies, it usesmore overtly aggressive, less internationally 'acceptable'measures to protect the national capital. The mouthpieceof the British industrial bourgeoisie, the Confederation ofBritish Industry, shows the way things are going:'In the 'eigh tiesthe competitionfor tradewill besosevereandour problemsof industrialregenerationin Britainso difficultthatwemusturgeGovernmentto makethe trade consequencesa "firstcharge"on everyforeignpolicy decisionthey ponder.As such itmaywelloutweighdiplomaticandUN considerationsand thoseof adomesticpoliticalnature.Thisshouldbe reflectedalsoin theMinis-terial time and eff0!J devotedby the Governmentas a whole totradepromotion... .' 1

1M SeeTable 11 on overcapacitykvels and Section2 on com-petitionin theworldmarket.19 For a discussionof thebourgeoisstateseeFRichards,'Revision-ism, Imperialismand the state', Revolutionary CommunistPapers No4, February1979.20 Ausefulinternationalsummaryof the formsof stateinterven-tion is providedin the survey'The state in the market',TheEconomist, 30 December1978.21 CBI,International trade policy for the 1980s, August1980.

2. THE COLLAPSE NOW

To understand the extent of the crisis today we must seehow the capitalist world recovered from the 1974-75 reces-sion. That recession was the worst experienced by the Westin the post-war period. Every capitalist power was affected:production and investment slumped, inflation and unem-ployment rates rose dramatically and international tradefell. When an upturn followed, it proved very partial incharacter. Despite the renewed growth of production, thesymptoms of crisis persisted. All the key indicators showedthat the world economy was in a worse state than in theyears prior to 1974. The recession was no mere passingphenomenon .1

After 1974-75 a number of existing traits of the worldeconomy began to be accentuated as capital sought an exitfrom its crisis. Both national and international credit expan-ded, reliance on trade increased, and the export of capitalbecame more frenzied. Below we show how these develop-ments helped to sustain a mild recovery over the years1975-79 - and how, by lifting the accumulation of capitalto a higher level, they merely made the contradictions ofthe system sharper.We discuss each development separately, though thereare many interconnections. The aim is not to givea historyof the 1974-79 period, but to provide the basis for explain-ing the crisis today. We focus upon the major imperialistcountries, which together account for more than half theworld's economic output and trade and which are thedecisive factors in the world today.

Either a borrower or a lender be

Both private and state credit have played an important rolein counteracting capitalist stagnation. This applies equallyto national and international credit.(a) National credit expansionThe country in which national credit expansion has beenmost significant is the USA. The American economy ralliedremarkably after the 1973-74 recession - industrial prod-uction rose by nearly 30 per cent and unemployment fellby almost two million, 1975-79; but it did so largelythrough credit. As the OECD put it in 1980, 'borrowing tofinance both housebuilding and consumption has been onan impressive scale'.2 Between 1975 and 1978, mortgagedebt rose 54 per cent to $750 billion, consumer instalmentdebt by 49 per cent to $300 billion and corporate debt by36 per cent to more than $1 trillion (a trillion is a millionmillion). At the same time total US government borrowingrose 47 per cent to $825 billion. Total private and publicsector debt soared from $2.5 trillion in 1974 to a colossal$3.9 trillion in 1978.3 By comparison, America's GNPstood at $2.1 trillion that same year. The enormous risein America's debt reveals how superficial its industrial up-swing has been. That most of the rise has occurred inconsumer or government debt rather than in borrowing for

1 See the Editorialin Revolutionary Communist Papers, No6,June 1980.2 Economic Outlook, July 1980.3 Business Week, 16October1978.

7

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

10/41

investment purposes confirms that the USA has beenaccumulating IOUs rather than accumulating capital."Credit has helped raise US production levels but has donelittle for overall productivity. Between 1974 and 1979 USproductivity grew at an average rate of merely 0.1 per centper year.s On the other hand inflation rose continuallyfrom 1976 onwards, eventually reaching record highs. Theunderlying decline of US competitiveness also registered inunprecedentedly large trade deficits. Today, when IOUs falldue, many firms find themselves unable to meet their debts.Last year, for instance, bankruptcies in the USA reachedrecord levels.The main effect of the USA's credit-based boom wasnot on the structure of US capitalism, but on its relationswith the rest of the world economy. Exports to the USAmultiplied rapidly and foreign capital flooded in to takeadvantage of the growing domestic market.National credit expansion has not been confined to theUSA. While the Labour Government was busy cuttingpublic expenditure in Britain, consumer credit here morethan doubled from the end of 1976 to a total of 7.8billion at the end of 1979.6 In West Germany, consumercredit rose by 80 per cent to DM93.2 billion over the sameperiod, and government debts rose from 24.5 per cent to29.4 per cent of GNP between 1975 and 1979, totallingsome DM450 billion in 1980? We should remember,however, that countries more reliant on imports than theUSA run higher risks than it does when they expand theircredit. They do not have the same room to manoeuvre asthe USA, and cannot therefore give rein to credit in theway it can.(bl International credit expansionThe international credit markets have grown prodigiouslyover the past decade. In particular the Euromarkets havewidened from $150 billion in 1971 to nearly $1200 billionin 1979.8 For governments, large corporations and banksthey represent one of the few sources of readily availablelarge-scale capital.A major reason for the flourishing of the Euromarketshas been that OPEC deposited its dollar-denominated oilrevenues, or 'petrodollars', with Western banks, which inturn have lent them out via the Euromarkets to countriesfacing balance of payments deficits. After the 1973-74 oilprice increases the Euromarkets were used as the mainmechanism for 'recycling' petrodollars to indebted nationsin general and near-bankrupt backward capitalist countriesin particular. The principal effect of this was to allow back-ward capitalist countries to maintain or increase imports ofWestern commodities. As a result the decline in Westernexports slowed down and the impact of the recession wassoftened.'Recycling' is, however, no solution to the West's prob-lems. For the West to loan money to backward capitalistcountries so that they will have enough to buy its goods ispatently self-defeating. What has happened is that theburden of debt has begun to weigh down on backwardcapitalist countries more heavily than ever - especially forthe 'middle-income' states which make up significantmarkets for imperialist exports." For these countries exter-nal public debts rose on average from 10.8 to 17.6 per centof GNP between 1970 and 1978. Today merely payinginterest on that debt takes up a large proportion of thesenations' export earnings. In 1978 the ratio of debt servicecharges to export earnings was more than 30 per cent inPeru and nearly 60 per cent in Mexico.t? Backward capital-ist countries cannot go on like this, and nor can theircreditors.

Last year OPEC's surplus revenues were estimated at

some $120 billion, and the trade deficit of 'non-oil prod-ucing developing countries' at about $70 billion.ll Butrevenues cannot be recycled into deficits as before. Theirclients faced with mountains of debt, Western banks arereluctant to go on lending funds out and so risk a default.The sums involved are vast and the consequences of abanking crash devastating. According to a recent survey onworld banking, the underdeveloped countries now figure as'one of the greatest single difficulties facing internationalbanks today,.12 No wonder that, to protect their loans, theimperialist banks are moving towards imposing 'political 'safeguards of a markedly colonial character.v'

Buy cheap, sell dear

Trade has become crucial for the imperialists in the crisis;indeed the house-trained economists of each capitalistcountry look to exports as a means of overcoming thestagnation of their domestic economies.v" Between 1970and 1978, the exports of the 18 leading capitalist countriesgrew at an annual rate of 5.7 per cent, while industrial out-put increased at only 3.4 per cent.IS As a result there wasa marked increase in the ratio of trade to GDP. Table 6shows this. Even the relatively self-sufficient US economyhas become more dependent on trade and thus more vulner-able to changes in the world economy.t''

Table 6 Trade as a proportion of GOP (per cent)1968 1978

UKUSACanadaJapanWest GermanyFranceItaly

29102510262024

2152110211416

Source: Bank for International Settlements, 50th Annual Report,1 April 1979-31 March 1980

Naturally enough, exports have been attracted tocountries whose markets have been growing fastest. Thusbetween 1975 and 1977 exports to the USA more thandoubled in dollar terms to $207 billion and the fractionof total OECD imports accounted for by the USA alsoincreased.V But, since the first oil price rises in 1973, themost significant new export market has been OPEC: itsimports have on average been rising by more than 20 percent a year. Table 7 shows how the share of exports goingto OPEC has doubled for most industrialised countries overthe past few years. Taken together, the OPEC countriesnow comprise Britain's biggest single export market. It isnot surprising that the imperialists show themselves socon-cerned about political stability in the Middle East. Not onlytheir oil interests, but a considerable portion of their tradeis at risk there.OPEC has not been alone in boosting Western exports.In contrast to the 'sixties, when they took an ever-decliningshare of industrial country exports, the backward capitalisteconomies have come into their own as vital markets forimperialist commodities. Table 8 shows this clearly.

8

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

11/41

Table 7 Exports to OPEC as percentage of total exports181972-73 1978 1979 1980(first half)

UK 6.0 12.1 8.0 8.8USA 5.3 11.6 8.3 7.6Canada 1.2 2.9 2.4 2.6Japan 7.1 14.6 13.1 14.9West Germany 3.3 8.6 6.1 6.2France 4.7 8.2 7.7 8.5Italy 5.4 12.6 10.8 11.9Seven major countries 4.7 10.5 7.3 7.5TotalOECD 4.1 9.3 8.1 8.5Source: OEeD, Economic outlook, December 1979 & December1980

Table 8 Importance of developing countries as markets for themanufactured exports of industrial countries (per centshare of total exports)

1973 1978NORTH AMERICAN EXPORTS 5To Western Europe & Japan 29 26 6To developing countries 24 32JAPANESE EXPORTS 7To North America &Western Europe 47 44To deve'loping countries 42 46 8WESTERN EUROPEAN EXPORTSTo North America & Japan 11 9,To developing countries 15 20Source: GATT,Inrernational Trade 1978/79, Geneva,1979

Carving up the worldThe growing importance of exports for the imperialist coun-tries is paralleled by the emergence of regional tradingblocs. Here the EEC is a case in point. More than half oftotal exports from EEC countries go to other memberstates.l" Seven of Britain's top ten export markets areother EEC countries: having taken 36 per cent of Britishexports in 1976,they took 42 per cent in 1980.20 For WestGermany, Britain's largest trading partner, the figures aremore striking still. All of its top five export markets areother EEC countries, and the proportion of its exportstaken by these five has risen from 42 to 46 per cent,1977-79.21Since the EEC has to import 90 per cent of its rawmaterials itmaintains strong links with backward capitalistcountries. Through the Lome Convention, it has trade andaid pacts with 57 African, Caribbean and Pacific states -the so-called ACP countries, most of which are in Africa.22In addition the EEC has special trade agreements with theAssociation of South East Asian countries (ASEAN -Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thai-land) and with Latin America in order to boost exports ingeneral and capital goods exports in particular.Japan and the surrounding countries in South East Asiaand the Pacific form another important trading bloc. As agroup they are growing faster than the economies ofEurope and North America, and they are becoming moreintegrated - though Japanese hegemony is undisputed.Japan's neighbours conduct 30-40 per cent of their tradewith it and have taken to holdinf yen in their foreignexchange reserves to finance this.2 Japan can, as a con-

sequence, now afford to price almost a quarter of itsexports in yen, as opposed to the once-unrivalled US dollar;before 1973 the proportion was little over 10 per cent.24

4 The US economy is becoming more and more impervious tothe stimulus of credit. Though consumer credit has grownfaster, GNP growth has been sluggish and both unemploymentand inflation have got worse:Period*: 1961(Ql) 1971(Ql) 1975(Ql)-1969(Q3) -1973(Q2) -1979(Ql)Average annual growth inconsumer credit, per cent 9.6 13.3 14.5Average annualGNP growth, per cent 4.6 5.1 5.0Average unemployentrate, per cent 4.7 5.5 7.1Average annual increase inconsumer prices, per cent 2.5 5.1 7.2*(Q) denotes which quarterSource: OECD, United States, November 1979The Economist, 26 July 1980.Central Statistical Office (CSO), Financial Statistics, Septem-ber, 1980.OECD, Main economic indicators, September 1980; FinancialTimes, 23 September 1980.Morgan Guaranty Trust Company, World financial markets,October 1980. In the Euromarkets banks deposit and lendmoney outside its country of origin. The term most commonlyrefers to transactions in US dollars that are carried out in themain financial centres of Europe. However a number of othercurrencies are also used in this way, although the dollar ac-counts for some three-quarters of the total business, and bankactivity in other centres like Hong Kong and the CaymanIslands is also incluued. In 1979, Euromarket credit extendedto industrial countries amounted to $2.7bn; that extended todeveloping countries $48.0bn. Th-emain reasons for the growthof the Euromarket are that banking operations are left relativelyunregulated in it and that capitalists can use it to bypass res-trictions on domestic borrowing.9 Bank lending has been concentrated on a relatively smaIlnumber of countries. In recent years about 70 per cent of thetotal has gone to Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, the Philip-pines and South Korea. See The Banker, July 1980.10 World Bank, World development report, 1980.11 The Banker, July 1980.12 Financial Times, 11 May 1981.13 Western bankers welcomed the military takeover of Turkey inSeptember 1980 precisely because it promised such safeguards.Increases in repression in debt-ridden countries such as Zaire,Peru and South Korea were greeted with equal enthusiasm.14 See for example The Economist, 16 August 1980.15 World Bank, op cit.i6 The US economy's dependence on trade, like that of its rivals,has increased up to the present day. See OECD,Main economicindicators, June 1981.17 British Business,S December 1980.18 The share of exports to OPEC fell in 1979, mainly as a resultof the revolution in Iran, and then recovered. In 1980, 10.1per cent of total UK exports went to OPEC.19 In 1979, the EEC accounted for 35 per cent of world trade;54 per cent of this figure was intra-EEC trade. British Business,13 March 1981.20 CSO, Overseas trade statistics of the UK, 1980.21 The Times, 27 June 1980.22 France and Britain, the main imperialist powers involved inAfrica, account for the largest shares of EEC exports to theACP countries. For an account of the Lome Convention, seeThe Economist, 27 October 1979.23 Euromoney, September 1980.24 Ibid.

9

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

12/41

Trade warThe imperialist powers' increased dependence on trade hasled to greater tensions in the world market. Since domesticmarkets cannot by themselves support accumulation, theimpetus to try to cut into overseas markets grows. At thesame time the pressure on competitive industries in everycountry to compete has sent inefficient national industriesto the wall and has helped form a new international divisionof labour at their expense. It is capitalists in these nationalindustries who have been most vociferous in calling on theirgovernments to 'control' foreign imports.In the USA a 'trigger price' system protects the domes-tic industry from much cheaper imports of steel from theEEC and especially Japan, South Korea and Brazil.25 Forits part, the EEC operates an extensive system of quotas(the Multi-Fibre Arrangements) on textiles exported to itfrom the 'new industrial countries' of Taiwan, South Korea,Hong Kong and so on. It also protects its agriculturalproducers through the infamous Common AgriculturalPolicy system of tariffs. And, as if this was not enough,EEC chemicals producers have been protesting about'unfair competition' from US chemical imports. Still, theEEC and the USA have one thing in common: both haveforced Japan to limit its car exports - 'voluntarily', ofcourse.The struggle to hold or increase market shares hasbecome fierce. Indeed imperialist companies have shownthemselves prepared to trade at a loss so as to maintaintheir slice of the world market. For example: in 1980Imperial Chemical Industries, Britain's second largestexporter, increased its exports by five per cent at the sametime as it reported an extraordinary slump in profits. 26Trade war today is not only a matter of governmentprotection against imports. In every imperialist countrythe state has taken an active role in the export field too.Despite their laissez-faire philosophy, the Thatcher andReagan administrations have thrown their weight behindtheir exporters. In 1979-80, Britain's Export Credit Guaran-tees Department underwrote loans to the tune of 500million. France and Japan have also made a speciality ofoffering indigenous exporters cheap loans, which theydelicately term 'development aid,.27 Things have come tosuch a pass that, earlier this year, the USA's Export-ImportBank agreed to finance bids by Kaiser Engineers Inc andMotorola Inc for projects in the Ivory Coast in a clearattempt to beat off tenders made by private but state-aidedFrench firmS.28 There now exists an export credit war, onewhich has suspended free trade for good. The FinancialTimes has been moved to complain: 'Companies no longercompete freely for overseas capital project contracts. Thewhole market has become hopelessly distorted by govern-ment intervention and subsidy,.29

Capital export

Britain and the USA have been, and still are, the imperialistpowers with the most capital investments abroad. UK totalprivate investment overseas amounted to just over 34billion at the end of 1979; that for the USA amounted to$193 billion.3o Although smaller in absolute terms, Brit-ain's investments abroad are larger when compared toGNP. The same is true of Britain's annual outflow ofinvestment. 31Both countries rely heavily on the profits they makeabroad. In 1979 overseas profits accounted for at least a

third of the overall profits of most of the top 100 US multi-national corporations and banks;32 US corporations alonemade $37.8 billion profits from overseas investments.33IBM makes well over half its total profits outside America,while all of the profits of Ford and General Motors camefrom overseas operations last year, such was the crisis thesecompanies met with at their US plants. In the case ofBritain, repatriated profits from direct investments overseas(excluding those made by oil companies) amounted to769 million in 1979 and total profits to 2.5 billion - notbad against a figure for gross trading profits made in Britainof 19.6 billion.34Overseas investments do not just bring in profits. Theyalso stimulate the export of commodities. Nearly 30 percent of Britain's exports, for instance, are made to overseassubsidiaries of British companies.35These figures in capital exports indicate the structuralweakness of British and US imperialism. But, since the late'sixties, the limited scope for domestic accumulation inWest Germany and Japan has also forced these countriesto increase their foreign investments. Between 1965 and1971 the value of overseas investment rose at an annualrate of 29.4 per cent for Japan and 22.8 per cent forWest Germany to reach $4.5 billion and $7.3 billionrespectively.r" In 1979, net capital investment abroad fromWest Germany rose by DM8.4 billion to a total of DM61.6billion.37 A similar pattern can be discerned in relation toJapan: estimated at $31 billion in 1979, total foreigninvestment there is expected to rise to $79 billion by1985.38 The emergence of West Germany and Japan asmajor capital exporters reflects the growing shift in thebalance of world economic power.

The changing balanceThe relative decline of Britain and the USA can be seen inother ways too. First, these two countries are importingcapital faster than they are exporting it (although theabsolute size of capital exports is still greater). Foreigninvestors have been quick to take advantage of the growthin the US market since 1974, as Table 9 shows, and WestGerman and especially Japanese capital exports haveshot up.39

Table 9 Foreign direct investment stock in the USAIS m at year-end)1974 1978 % growth

UK 5744 7370 28.3Canada 5136 6166 20.1Japan 345 2688 679.1West Germany 1535 3191 107.9France 1139 1939 70.2Netherlands 4698 9767 107.9Switzerland 1949 2844 45.9Others 4598 6866 49.3Total 25144 40831 62.4Source: S Young & N Hood, 'Recent patterns of fore ign directinvestment by British mult inational enterprises in the UnitedStates', National Westminster Bank Quarterly Review, May 1980

The form taken by each country's overseas investmentsindicates how the balance of world economic power ischanging. While West German and Japanese firms tend to

10

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

13/41

establish new points of production and so come to rep-resent a direct challenge to their competitors, British invest-ment in the USA, at least, has been of a less dynamic type,proceeding largely through acquisitions of and mergers withUS companies rather than through the construction of newplant or the expansion of existing subsidiaries.4o

More and more of Britain's overseas investment goesinto non-industrial projects. Table 10 shows that directinvestment by banks and insurance companies, like port-folio investment (the purchase of overseas equities andsecurities), is increasing faster than direct investment byindustrial and commercial companies. Unable to compete inworld markets, British imperialism is reduced to playing awholly parasitic role.

Table 10 UK private sector external assets (m at year-end)1977 1978 1979 % growth

Direct investment* 14800 15800 16500 11.5UK banks' direct investment 1152 1341 1897 64.7Oil companies' net assetsabroad 3550 3900 5250 47.9Insurance companies' direct 36investment in USA 595 610 710 19.3Portfolio investment 6900 8050 9500 37.7Other 156 267 37Total 26995 29855 34125 26.4Source: Bank of England Ouerterty Bulletin, June 1980 3839*Note: By industrial and commercial companies; excludes oilinsurance and banking companies.

At the end of October 1979, the British Governmentabolished exchange controls. Purchases of overseas sharesand bonds by UK financial institutions increased dram-atically. The total capital outflow was estimated at about2 billion, most of which took the form of portfolioinvestment. In 1979, earnings from direct investments inbanking and insurance and from portfolio investment over-seas amounted to 928 million, compared to 804 millionin 1978.41 If this goes on, Britain will soon be doing littlemore than what Lenin described as 'clipping coupons'.The growing power of Japan and West Germany is alsovisible in the international capital market. Parallel to theemergence of regional trading blocs, distinct financialspheres of influence have begun to develop.For most of the post-war period the USA held thedominant position in international finance. The bulk ofworld trade was priced in dollars; the dollar formed thebasic asset of the foreign exchange reserves of the world'scentral banks, and was the most common currency fordenominating international loans and bond issues in. Thisworked to the benefit of US imperialism, for the purchaseof dollars by foreign governments and corporations helpedfinance its balance of payments deficits, while foreignacceptance of dollars allowed it to buy up plant abroadwith ease. However, because of the downward trajectory ofUS imperialism, a new situation has taken shape in theworld financial sphere.42 Declining US competitiveness andrising balance of payments deficits, by weakening the valueof the dollar in foreign exchange markets, have led othercountries to look for alternative ways of holding theirwealth and settling their accounts. One has been to usegold.43 The other has been to use the yen and the Deutsche

25 The Economist, 12 July 1980.26 Financial Times, 27 February 1981.27 Midland Bank Review, Autumn 1980.28 Business Week, 19 January 1981.29 Financial Times, 15 May 1981.30 Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin, June 1980; US Depart-ment of Commerce, Survey of Current Business (SCB), August1980.31 British Business, 1 February 1980.32 Business Week, 12 March 1979.33 SCB, August 1980.34 CSO, UK balance of payments, 1980.35 Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin, March 1980. Most foreigninvestment from the USA and Britain is located in other devel-oped capitalist countries. However, for the USA the proportionin backward countries has risen from 21.2 per cent in 1975 to24.8 per cent in 1979. The reason is not hard to see: in 1979the rate of return on US investments in backward capitalistcountries was 28.9 per cent, while that on US investments inthe developed economies was 18.9 per cent. In the case ofBritain, about 20 per cent of overseas capital is located indeveloping countries and some 20 per cent of overseas profitscomes from these areas.C Palloix, 'The self-expansion of capital on a world seale',Union of radical political economists, Vol 9, No 2, USA,Summer 1977.Calculated from Monthly report of the Deutsche Bundesbank,April 1980 and November 1980.Business Week, 16 June 1980.Capital flows abroad to attract a higher rate of return. Thisdoes not imply that the overall rate of profit in a capital-exporting country has to be less than that which obtains in thecountry to which capital flows. We have to look at the sit-uation for individual branches of industry and the firms con-cerned. A Japanese electronics company, for instance, maysecure a better return on investment in the US market than athome simply because it is more competitive there.40 See S Young & N Hood, 'Recent patterns of foreign directinvestment by British multinational enterprises in the UnitedStates', National Westminster Bank Quarterly Bulletin, May1980.41 Figures calculated from CSO, UK balance of payments, 1980.We are talking of the decline of Britain, a senile imperialistpower. David Reed of the Revolutionary Communist Group,however, prefers to exaggerate the size of banking capital toprove the absurd thesis that British imperialism is gaining instrength (Fight Racism! Fight tmperialisml , No 6, September/October 1980). Me notes that in 1979 UK banks had overseasassets worth dS.5bn and declared that this sum 'dwarfs allother investment abroad'. But what kind of 'investment' isthis? 121bn was made up of foreign currency advances andoverdrafts. For the banks these assets are balanced by liabil-ities, that is deposits. Although banks earn interest accordingto the volume of lending, they must also pay interest ondeposits so total loans cannot be compared with the assets ofan industrial company. In fact through credit operations bankscan multiply the size of their assets without any real increaseof the capital on which they are based. Banks today often lend30 times the value of their market capitalisation! Reed alsoconfuses Britain's role as an international financial centre withthe strength of British banking. Over 80 per cent of the assetsoverseas to which he refers were advanced by foreign banks inBritain (mainly in the City of London) not by British banks!42 Between 1974 and 1979 the percentage of international loansdenominated in dollars fell from 78 per cent to 63 per cent;the percentage of gross international bond issues denominatedin dollars fell from 63 per cent to 42 per cent. Only the mas-sive growth of the overall market prevented a glut of unwanteddollars and a major crisis in the financial sphere, (FederalReserve Bank of New York, Quarterly Review, Summer 1980.)43 See 'Behind the dollar's demise', the next step, No 2, January1980.

11

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

14/41

Mark, even though the dollar is still the main currency forforeign exchange reserves.f?Both Japan and West Germany relaxed restrictions onthe international use of their currencies during 1980. Whilestill anxious that speculation in the yen and the DM mightdestabilise their economies, balance of payments deficitsconsequent on dearer oil forced them to make a move.Their rulers realised that extra overseas currency holdingscould finarice these deficits - and allow capital exports togo on surging ahead too. Thus the yen is now the secondmost important investment currency - after the dollar -for the deployment of surplus OPEC revenues. So muchmoney has poured into Japan in the form of yen depositsand purchases of bonds and equities that Japan had littledifficulty in financing its $15 billion deficit in 1980.45The lines of division in the international capital mar-kets reflect and reinforce the spheres of influence of theimperialist powers. London is the main centre of the Euro-market and receives the largest share of OPEC revenues(in dollarsk relending these to other markets and othercountries.f The US national market and the Caribbeanoffshore market, from where many US banks operate also,are the main sources of loans to Latin America; banks inJapan are the most important for financing trade in Asia;and the credit markets in Europe, particularly Londonand West Germany, are the main lenders to the Comeconcountries.V

Bottoming out?

The forces brought into play to counteract the recessionafter 1975 have had only a limited effect. The expansionof credit, the growth of trade and the rise in capital exportshave not prevented a further recession beginning in 1980.In fact it is the use of precisely these safety valves of thepast that has brought on the crisis of today.Credit cannot play the same counter-crisis role that itdid before. The bourgeoisie has recognised that, thoughcredit can foster investment, this tends to depress profitlevels.48 Moreover credit encourages prices to rise. TheOECD Secretariat, which up to 1978 called on the majorimperialist powers to embark on a 'concerted reflationaryaction programme', now stresses that the reduction ofinflation is 'top priority,.49The capitalist system cannot survive without credit.But the bourgeoisie is now more interested in raisinginterest rates to restore financial stability than in stimul-ating production artificially. This is reflected in the shifttowards 'supply-side' economics, an approach whichemphasises the need to reorganise industry and whichscorns credit expansion. Thus the OECD Secretariat notes

the 'growing body of opinion' which is of the view that, inits current form, state intervention in industrialised econ-omies may have weakened their 'responsiveness to changesin aggregate demand'. It calls on governments to improveworking of markets' and to encourage 'economic agents' toaccept 'changes in work and, perhaps, life styles (sic),.5oIn other words, it advises the capitalists that the only waythey will save their system is to cut state expenditure, jackup the rate of exploitation in the factories and get widerand wider layers of the working class accustomed to a newway of living - unemployment.The bourgeoisie must curb the growth of credit if it isto avoid financial instability. A default on loan repayments,an adverse movement of interest rates, a major loss on theforeign exchange and commodity markets - any of thesemishaps could precipitate economic collapse. Today central

bankers lead anxious lives, concerned that they are over-extending their loans (particularly to unstable backwardcapitalist countries) and worried about the shady dealsother members of the 'financial community' get into tomake a quick profit. The state is always ready to step in,but the gigantic sums of money required of it make regain-ing control in a financial scare harder and harder .51While the expansion of credit in the past decade hasmade a major financial crash more likely. the internationalintegration of the world economy established by trade andcapital export over the same period has raised the intensityof competition to unheard of levels. The destruction ofwhole national industries is now on the cards as worldimperialism tries to gear up for a new round of capitalaccumulation.For the capitalists the problem presents itself as surpluscapacity - capacity which must be eliminated if profit-ability is to be restored. Table 11 shows how the dimen-sions of that problem have grown.

Table 11 Manufacturing industry capacity utilisation rates1(percent)Average Average 1979 19801964-73 1974-78 Q2 Q42 Q2 Q4

UK 45.0 32.0 44.0 38.0 30.0 15.0USA 85.5 80.5 85.9 84.4 77.9 79.2Canada 87.0 84.5 84.6 84.3 79.5 79.9Japan 92.6 84.9 92.3 92.7WestGermany 86.4 80.0 85.6 84.5 83.8 78.6France 84.8 82.7 81.9 81.8 83.0 SO.OItaly 78.5 73.2 75.2 77.6 76.6 73.0Source: OECD, Main economic indicators, May 1981 and EconomicOutlook, July 1980Notes: 1. Each country's utilisation rate is defined difterently so

the seriescannot be compared.2. The figure for Japan is for the third quarter of 1979.Later figures are not published, but the operating rate formanufacturing industry fell by 6 per cent between Decem-ber 1979 and December 1980. Japan Economic Joumal,27 January and 26 May 1981.

How fast surplus capacity can be got rid of depends onhow much profitable areas for investment are available.Surplus capacity has been destroyed most effectively inJapan, the most dynamic of the imperialist powers. Bet-ween 1976 and 1979, Japan reduced shipbuilding capacity35 per cent, sending 37 medium-sized yards into liquid-ation. Meanwhile, assisted by state loans, capital has movedinto new and lucrative sectors such as electronics.52Where capitalists hang on to outdated technology, asUS automotive firms have, competition exacts a severeprice. In 1980, Japan for the first time surpassed the USAas the world's leading car manufacturer, US car output fellback to 1959 levels, the major US motor corporationsracked up combined losses of $3.7 billion within ninemonths and imports rose to new peaks.53 On the otherhand, vigorous rationalisation can pay dividends: it is thisthat has enabled the USA to emerge as an importantexporter of textiles, and to challenge EEC chemicalsproducers for sales on their home ground and in thirdmarkets.54Cutting capacity and rationalising industry are, how-ever, not merely technical questions. They go hand in handwith the process of disciplining the working class to accept

unemployment and low wages. Unemployment in the12

-

8/7/2019 Revolutionary Communist Papers 7 - 1981

15/41

world's seven major imperialist powers has leapt from 14million to 17 million over the last year, and even optimisticforecasters do not see a recovery generating many jobs. Asfor wages, these have generally been on a downward trendsince 1978.

Table 12 Real earnings in manufacturing industry1(per cent change on previous year)1976 1977 1978 1979 1980

UK 0.2 -5.6 6.2 2.2 -0.2 52USA 2.2 2.8 0.8 -2.7 -4.9 53Canada 6.5 2.5 -1.8 -0.3 0.1Japan 3.0 -o.s 2.1 3.8 0.0 54West Germany 1.1 3.7 2.8 1.1 0.0France 4.5 3.2 3.9 2.3 1.4Italy 4.1 9.5 4.0 4.2 1.3 55Source: British Business,5 June 1981Note: 1. Calculated by deducting consumer price increase from

increase in nominal hourly earnings.

Declining living standards are only a prelude to a morethorough offensive against the proletariat. Whether theindividual capitalist wins or loses the comjetitive struggle,it is the working classwhich has to suffer.5

44 After the Second World War sterling used to be a major reservecurrency; but by the mid 'seventies, in step with the decline ofBritish capitalism, its use as a reserve asset had dropped to neg-ligible proportions. Recently, now that the sterling exchangerate is buoyed up by exports of oil, it had made a minor come-back and is one of the currencies into which reserve assets havecome to be diversified. Over the past couple of years, thegrowth of a diversified reserve asset system has brought aboutwhat bourgeois commentators call an 'interest-rate war'. Eachimperialist power now uses interest rate increases relative to itscompetitors to attract flows of money capital. Matters soon getout of hand, as a recent chain of events shows. As US interestrates rocketed at the end of 1980, money capital flowed intoAmerica and drove up the dollar's exchange rate against othercurrencies. The DM, in particular, was hit badly, and in Jan-uary 1981 West Germany chalked up a ~2.5bn current accountdeficit as the cost of oil imports rose in DMterms. Bonn there-fore set about raising domestic interest rates at once, so as tostrengthen its currency. France and Switzerland followed suitso that interest rate levels rose to near-record highs. See Bus-iness Week, 23 March 1981. Interest wars add another elementof uncertainty to the ledger books of capitalism. High interestrates depress the level of investment in productive capital andslow economic growth. As exchange rates fluctuate in response,long-standing trade patterns are overturned. In the face ofphenomena it has no power to control the international bour-geoisie becomes more and more desperate.45 The Banker, November 1980. We have noted the growing roleof the yen in trade in South East Asia; we should also observethat the DM is the cornerstone of the EEC currency bloc, theEuropean Monetary System.46 London is also the main channel through which OPEC coun-tries are buying shares in the Tokyo stock exchange, under-lining the importance of the City of London as a world finan-cia! centre. See the Financial Times, 12 January 1981.47 See Amex Bank Review, 21 July 1980. Petrobras, the Brazilianstate oil company, is arranging with Citibank, the major USmternational bank, to borrow money on the US commercialpaper market: see the Financial TImes, 28 October 1980. WestGermany led the field in extending credit to the Polish govern-ment during its crisis last year.48 Between 1973 and 1980 investment in the USA's traditionalmanufacturing sector rose 4.8 per cent in real terms, yet profit-