Review Lute History

Transcript of Review Lute History

-

8/9/2019 Review Lute History

1/3

Renaissance Society of America

Review: [untitled]Author(s): Beth BullardSource: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 4 (Winter, 2003), pp. 1236-1237Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society ofAmericaStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1262031Accessed: 19/08/2010 23:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=rsa .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Renaissance Society of America and The University of Chicago Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1262031?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=rsahttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=rsahttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/1262031?origin=JSTOR-pdf -

8/9/2019 Review Lute History

2/3

RENAISSANCE QUARTERLYENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

modernEuropean

ulture. This is atruly

new look at emblems and emblem booksby a knowledgeable nd eloquent specialist n the field.DANIEL RUSSELL

University f Pittsburgh

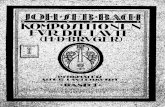

Douglas Alton Smith. A History of the Lute rom Antiquity to the Renaissance.Ft. Worth: The Lute Societyof America, 002. xvii + 389 pp. + 4 col. and 75 b/w pls. index.append. llus. $85. ISBN: 0-9714071-0-X.

This book represents massivescholarly ndertaking. Douglas Alton Smith, nthe preface, xplains his purpose and approach: oping to provide a missing "pan-oramic view," he chose "[1] to show in words and pictures how and why the lutechanged physically hrough he ages; [2] to give a general ntroduction o the lute'suse in society; [3] to trace he development of its cultural ymbolism; 4] to placethe major lutenists and composers n perspective biographically and musically;[5] to describe uccinctly he musical styleof each significant igure; nd [6] to sug-gest how the music of one may have nfluenced others" xii-xiii).

Smith succeedsadmirably n his first ntention. His selection and presentation

of pictures prove especially ffective n chapter 4, arguably mith's est: "Lutes ndLute Making n the Middle Ages and the Renaissance" 58-94, plus four pages ofcolor plates). Smith's econd purpose s also well served, as he explores ocietal usesof the lute. His third aim, tracing he instrument's ymbolism, ppears s a constantthroughout he book, supporting he author's entral hesis that "the ute was themusical mblem of humanism ... As long ashumanism held sway, he lute was theprince of instruments; when it waned, the days of the lute were numbered" 7).Smith's ourth, fifth, and sixth aims take up the bulk of the book. For these topics,the author acknowledges he shortcoming f his reliance n secondary ources and

its resulting mbalances, ince some areas have received more scrutiny han others.Thus, his treatment s fullest on Italy and England; omewhat ess on France, heLowlands, nd Spain; and weakest n Germany nd Eastern Europe. He would havebeen aided had he consulted my study and translation f Sebastian Virdung's rea-tise, Musicagetutscht, ublished n Basel n 1511 (Cambridge, 993). Smith s at hismost eloquent when commenting on composers nd their music of which he appar-ently has first-hand knowledge.

Dr. Smith begins his panoramic view in Greece, where, ironically, no luteexisted.Smith considers ncient Greek yresand kitharas, ecausehumanists duringthe European Renaissance misidentified he lute with these instruments, ransfer-ring the mythic and historical ales about hem to Renaissance thought and practice.Smith moves o the lute's rue antecedents n central Asia, notably Persia, hen to itsadoption by Arabs, among whom the lute held preeminence eginning hortly afterthe birth of Islam in 622. The lute traveled to Spain with Islam in about the ninth

century. Noting that Arabic translations of Greek classic writings rendered thewords "lyre" and "kithara" s "lute" (8), but not acknowledging the debt of the Westto Arabic scholarship, Smith fails to recognize how Arabic scholarship contributed

modernEuropean

ulture. This is atruly

new look at emblems and emblem booksby a knowledgeable nd eloquent specialist n the field.DANIEL RUSSELL

University f Pittsburgh

Douglas Alton Smith. A History of the Lute rom Antiquity to the Renaissance.Ft. Worth: The Lute Societyof America, 002. xvii + 389 pp. + 4 col. and 75 b/w pls. index.append. llus. $85. ISBN: 0-9714071-0-X.

This book represents massivescholarly ndertaking. Douglas Alton Smith, nthe preface, xplains his purpose and approach: oping to provide a missing "pan-oramic view," he chose "[1] to show in words and pictures how and why the lutechanged physically hrough he ages; [2] to give a general ntroduction o the lute'suse in society; [3] to trace he development of its cultural ymbolism; 4] to placethe major lutenists and composers n perspective biographically and musically;[5] to describe uccinctly he musical styleof each significant igure; nd [6] to sug-gest how the music of one may have nfluenced others" xii-xiii).

Smith succeedsadmirably n his first ntention. His selection and presentation

of pictures prove especially ffective n chapter 4, arguably mith's est: "Lutes ndLute Making n the Middle Ages and the Renaissance" 58-94, plus four pages ofcolor plates). Smith's econd purpose s also well served, as he explores ocietal usesof the lute. His third aim, tracing he instrument's ymbolism, ppears s a constantthroughout he book, supporting he author's entral hesis that "the ute was themusical mblem of humanism ... As long ashumanism held sway, he lute was theprince of instruments; when it waned, the days of the lute were numbered" 7).Smith's ourth, fifth, and sixth aims take up the bulk of the book. For these topics,the author acknowledges he shortcoming f his reliance n secondary ources and

its resulting mbalances, ince some areas have received more scrutiny han others.Thus, his treatment s fullest on Italy and England; omewhat ess on France, heLowlands, nd Spain; and weakest n Germany nd Eastern Europe. He would havebeen aided had he consulted my study and translation f Sebastian Virdung's rea-tise, Musicagetutscht, ublished n Basel n 1511 (Cambridge, 993). Smith s at hismost eloquent when commenting on composers nd their music of which he appar-ently has first-hand knowledge.

Dr. Smith begins his panoramic view in Greece, where, ironically, no luteexisted.Smith considers ncient Greek yresand kitharas, ecausehumanists duringthe European Renaissance misidentified he lute with these instruments, ransfer-ring the mythic and historical ales about hem to Renaissance thought and practice.Smith moves o the lute's rue antecedents n central Asia, notably Persia, hen to itsadoption by Arabs, among whom the lute held preeminence eginning hortly afterthe birth of Islam in 622. The lute traveled to Spain with Islam in about the ninth

century. Noting that Arabic translations of Greek classic writings rendered thewords "lyre" and "kithara" s "lute" (8), but not acknowledging the debt of the Westto Arabic scholarship, Smith fails to recognize how Arabic scholarship contributed

1236236

-

8/9/2019 Review Lute History

3/3

REVIEWS

toconflating

the lute with the ancient Greek nstruments. He alsoignores

late-antique and medieval biblical raditions, uch as translations f the Hebrew "kin-nor" (lyre) as "cithara," hich came to be glossed pictorially n a number of ways,including as lute or other string nstrument. During the twelfth to fifteenth centu-ries, the lute traveled mainly via Sicily,according o Smith - to other parts ofEurope, where the instrument and its music had their great flowering n the six-teenth century. The exception was Spain, where the guitar-shaped ihuela de [sic]mano uddenly ook its place. Smith's xplanation s plausible: ythe 1490s the lute,deemed too Moorish for Christian Spain, was expelled along with its Muslim and

Jewish players, eavingts Christian

practitionerso

adoptan

acceptablelternative

(the vihuela was strung, uned, and played ike the lute).This book has much to recommend t. Laudable, or example, s Dr. Smith's

inclusion of some women's history: in ancient Greece (6), in "the Islamic era"(8-10), in medieval Spain (16-18), and in the Italian Renaissance 102-06). How-ever, the book could have benefited from a heavier editorial hand. The minimalpunctuation makes many passages difficult to fathom. More annoying is lack ofcoordination between llustrations nd accompanying exts especially rue of themusical examples. Smith's ranslation policy, furthermore, s inconsistent; some-

times he givesthe original anguage, while at other imes he does not. Dr. Smith alsofrequently eavesa term or a person undefined at first mention, as if the book is writ-ten for those already knowledgeable about the subject. Smith often jumps toconclusions he has not given the reader ause to accept, using verb forms such as"must have been" and "surely s," or example,which would be more accurate f soft-ened to "might have been" and "would eem to be." Also troubling o the historianin me are nstances of anachronistic vidence, or example, he diagram f Germanlute tablature 51, fig. 16) reproduced o illustrate he system nvented n the mid-fifteenth century: his diagram was published n 1727 and based on one printed n

1536. Troubling o the anthropologist n me is Smith'soverriding oncentration nhistorical development oward a later period, thus obscuring he "thing" tself (apiece of music, a style, a treatise, etc.) in favor of its place in a chronologicalsequence. What "lute music" actually was at a given time is likewise obscured. For,if one relies primarily on what survives in notation, the repertoire appears to consist

only of what exists on paper. But music for lute was far more than that tiny tip of anenormous iceberg, the rest being built on what we cannot so readily see - oral tra-dition and improvisation. Indeed, much of the printed music for lute expresslypointed away from itself, being put forth as models for study and imitation. Our

conclusions need to reflect how much of the repertory for lute at the time encom-passed by this book was not static but ever moving - and not necessarily in thedirection or according to the categories we may superimpose on it today.

The panoramic view provided by Douglas Alton Smith is nevertheless of greatvalue, and it stands to spur another of Smith's hopes: to generate further studies thatwill clarify our picture.BETH BULLARD

George Mason University

1237