Review: Immunology of sinusitis, trauma, asthma, and … relationship develops between activation of...

Transcript of Review: Immunology of sinusitis, trauma, asthma, and … relationship develops between activation of...

Review: Immunology of sinusitis, trauma, asthma, andsepsis

Marianne Frieri, M.D., Ph.D,1 Krishan Kumar, M.D.,2 and Anthony Boutin, M.D.2

ABSTRACT

Background: This review article is important for allergists/immunologists and otolaryngologists. It discussed chronicrhinosinusitis, epidemiology, pathogenesis, innate adaptive immunology, nuclear factor–kappa B related to inflammation,sepsis, complement, reactive oxygen species, asthma, sinusitis, elderly pathogenesis, oxidative stress, depression, seasonalvariation, vitamin D, genetic susceptibility and sepsis, hereditary angioedema related to trauma and stress.

Objective: The objective of this review is to link chronic rhinosinusitis, epidemiology, innate and adaptive immunology,NF-kappa B related to inflammation, sepsis, complement, reactive oxygen species, asthma and sinusitis.

Methods: A literature search was conducted from several articles, prospective studies, recent reviews and earlier reports. Asynergistic relationship develops between activation of the innate immune system and the loss of organ barrier functions. Manycomplex factors, such as genetics, physical agents, mediators in the development of organ failure both in asthma, sinusitis,stress, depression and trauma, leading to posttraumatic organ failure. Asthma and sepsis, a common condition encountered inhospital environments remains an important cause of death at intensive care units where allergists/immunologists andotolaryngologists are frequently consulted. The patient’s immune surveillance could fail to eliminate the pathogen, allowing itto spread and there is a proinflammatory mediator release with inappropriate activation.

Conclusion: This review discussed chronic rhinosinusitis, sinusitis related to trauma, the innate and adaptive immunology,NF-kappa B related to inflammation, sepsis, complement, inflammation, reactive oxygen species, asthma pathogenesis, andasthma in the elderly, oxidative stress, depression, seasonal variation and vitamin D, cytokines, genetic susceptibility relatedto sepsis, hereditary angioedema related to trauma and stress.

(Allergy Rhinol 6:e205–e214, 2015; doi: 10.2500/ar.2015.6.0140)

The purpose of this review was to link chronicrhinosinusitis (CRS), epidemiology, innate and

adaptive immunology, nuclear factor–kappa B (NF-�B) related to inflammation, sepsis, complement, reac-tive oxygen species (ROS), asthma, and sinusitis forallergists immunologists and otolaryngologists. Patho-genesis in the elderly, oxidative stress, depression, sea-sonal variation and vitamin D, trauma and cytokines,genetic susceptibility related to sepsis, hereditary an-gioedema (HAE) related to trauma and stress also werecovered.

CRS is a multifactorial disease with impaired ostialpatency, mucociliary impairment, allergy, bacterial orfungal infection, an immunocompromised state, andenvironmental and genetic factors thought to be asso-ciated with risk factors. CRS has been defined as per-sistent symptomatic inflammation of the nasal andsinus mucosa that results from the interaction of multiple

host and environmental factors.1 On epidemiologicgrounds, some association has been found between CRSprevalence and air pollution, active cigarette smoking,secondhand smoke exposure, perennial allergic rhinitis,and gastroesophageal reflux.2

CRS is broadly classified into two groups: CRS withnasal polyposis and CRS without nasal polyposis.Many definitions of CRS with nasal polyposis exist,and estimates of its prevalence vary.3 Estimated prev-alence ranges widely, from 2% to 16%. It is more com-mon in female subjects, ages 18–64 years, and in south-ern and midwestern regions of the United States. CRSis more prevalent in patients with comorbid diseases,such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-ease, and environmental allergies. Few studies exam-ined patient ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geo-graphic location, and cultural factors in the CRSpopulations.

EPIDEMIOLOGYThis article provides an overview of the epidemi-

ology, racial variations, and economic burden ofCRS.4 Despite active research in tertiary care settings,an understanding of CRS etiology, its natural history,and geographic and racial variation requires thoroughdata entry at the level of primary care settings, emer-gency departments, and otolaryngologists. Only by the

From the 1Division of Allergy Immunology, Department of Medicine, and 2Depart-ment of Emergency Medicine, Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, NewYorkThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare pertaining to this articleAddress correspondence to Marianne Frieri, M.D., Division of Allergy Immunology,Department of Medicine, Nassau University Medical Center, 2201 Hempstead Turn-pike, East Meadow, NY 11554E-mail address: [email protected] © 2015, OceanSide Publications, Inc., U.S.A.

Allergy & Rhinology e205

use of validated universal definitions for CRS, well-defined methodology in epidemiologic research, andaccurate entry of disease variables will it be possibleto obtain epidemiologic data on the natural evolu-tion of the disease and its socioeconomic factors, andthereby make advances toward disease prevention.4 Arecent article listed the presentation of available liter-ature on CRS epidemiology rhinosinusitis: epidemiol-ogy and cost.4 Understanding CRS allows us to char-acterize and differentiate the heterogeneous pathologyof chronic sinonasal inflammation based on histopa-thology, inflammatory pattern, cytokine profile, andremodeling processes. Epidemiologic studies are ur-gently needed to fill the immense gaps in knowledge,and a fundamental reconsideration of CRS as a chronicepisodic disease may provide a critical framework withwhich future studies can conceptualize this epidemic,which silently claims a heavy individual and societaltoll.5

An article reviewed insights that surround the etiol-ogy and pathogenesis of CRS and highlighted the in-creasing recognition of host-mediated mechanisms indriving mucosal inflammation, and it published differ-ences between epithelium from patients with CRS andnormal controls, and classified several broad catego-ries.6 Alterations were reported in the various compo-nents of the epithelial innate immune system, includ-ing epithelial-expressed pattern-recognition receptorsand the levels of antimicrobial innate immune effectormolecules. Other studies demonstrated differences in theproteins involved in maintaining epithelial barrier integ-rity. Recent studies showed that, in CRS, epithelial-derived cytokines, chemokines, and inducible surfaceproteins are involved in recruiting and activating cellsof the adaptive immune system.6

The sinonasal epithelium provides a mechanical andinnate immune barrier to a diverse array of environ-mental agents. This barrier also plays a key role inregulating the acquired mucosal immune response inthe nose. Results of recent studies indicated that de-fects in this barrier may foster the development ofchronic sinonasal inflammation in response to environ-mental agents and pathogenic or commensal organ-isms. The ability to dissect and analyze defects in theinflammatory response in rhinosinusitis may helpidentify novel targets for drug development.6

CRS is the second most common chronic medicalcondition in the United States and represents a groupof disorders characterized by inflammation of the nasalmucosa and paranasal sinuses. CRS with or withoutnasal polyps is defined as inflammation of the nosecharacterized by two or more symptoms, either nasalblockage, obstruction, congestion, or nasal dischargewith or without facial pain and/or pressure; and/orwith or without reduction or loss of smell.7

Patients who undergo endoscopic sinus surgery(ESS) are at risk of complications due to the closeproximity of the sinuses to the orbit and anterior skullbase. A prospective study evaluated the complicationsof ESS and identified patient characteristics that arerisk factors for the complications.8 The study was con-ducted with 706 patients who underwent ESS for CRS,and patients completed preoperative examinations thatincluded computed tomography; endoscopic observa-tion for nasal polyps; and tests for comorbidities, in-cluding asthma and vascular disease.8 Perioperativecomplications were evaluated based on informationprovided by the surgeons. Multivariate analysis wasperformed to identify patient characteristics that wererisk factors for complications. Perioperative complica-tions occurred in 41 patients; a major complication,cerebrospinal fluid leakage, occurred in one patient;and minor complications occurred in 40 patients, withthe most common being intraoperative hemorrhage.Multivariate analysis indicated that the presence ofasthma and the total polyp score correlated signifi-cantly with the occurrence of complications.8 Thus, therisk factors for perioperative complications wereasthma and the polyp score; the surgeon should con-firm whether the patient has lower airway disease,especially asthma, before operating and also shoulddetermine the grade of nasal polyps.8

Current literature related to asthma diagnosis, epi-demiology, pathogenesis, and treatment linked withrhinosinusitis is important. Asthma is very heteroge-neous; new theories and treatments are emerging.Asthma is a growing epidemic among children andadults in the United States. The severity of asthma iscaused by many factors, such as a lack of education,poor early recognition, decreased symptom awareness,improper medications, and phenotypic changes. Ge-netic variation, innate immune genes, those involvedin tissue remodeling and arachidonic acid metabolism,and inflammatory mediators might contribute to thepathogenesis of CRS linked with asthma.9 This exten-sive review addressed concepts of the burden ofasthma and sinusitis, altered innate immunity, adap-tive immunity, asthma remodeling, the airway epithe-lium, the role of airway smooth-muscle cells, unitedallergic airway, genetics (an integral part in asthma),and CRS.9 The role of vitamin D in both asthma andCRS in the elderly and in pediatric populations, vari-ous treatment options, exhaled nitric oxide, the linkwith CRS and biofilms, CRS phenotypes, and the treat-ment of asthma and CRS were also briefly addressed.9

Microbial biofilms have been implicated in thepathogenesis of CRS with nasal polyposis Althoughbiofilms are characterized by an extremely high resis-tance against chemical and physical agents, low-fre-quency ultrasound treatment has been suspected to bean efficient and safe method for biofilm disruption.10

e206 Fall 2015, Vol. 6, No. 3

CRS is a highly prevalent disease in the adult andpediatric populations, and causes significant burden,and the management is considered one of the mostcostly public health conditions; comorbidities includeasthma, aspirin sensitivity, and nasal polyposis.11 Staph-ylococcus aureus biofilms and exotoxins that act as su-perantigens have been implicated as playing an impor-tant pathologic role in the incidence, maintenance, andongoing burden of CRS. A better understanding of theinterplay between bacterial factors, host factors, andthe environment will facilitate better management ofthis disease. This literature review focused on thesefactors and highlighted current research in this field.11

Eradicating the bacteria without the biofilm leaves thepotential for future infections, and another generationof bacterial cells can inhabit the biofilm, which allowsinfection to persist, likely even more virulent becausetime allows for more-resistant mutations.11

Midface fractures commonly occur after trauma tothe face and may cause changes in the normal sinusoutflow system. A study examined the incidence ofrhinosinusitis after midface fractures and reported thatpatients who experienced a midface fracture had amuch higher risk of developing CRS that negativelyaffected their long-term quality of life. These patientsshould be monitored with long-term follow-up andtreated appropriately.12

SINUSITIS RELATED TO TRAUMATrauma to the anterior pituitary by a metallic foreign

body from the right nostril to the sella, responsible forpanhypopituitarism and sinusitis, has been reported.13

The direct trauma to the pituitary gland by a metallicforeign body is exceptional, and this report of ne-glected panhypopituitarism, discovered 31 years afterinjury with a pair of scissors, was found. Given the ageof the trauma, the patient refusing any surgery, and thesurgical risks of a possible extraction of the metal ob-ject, abstention was required.13

Changes in maxillary sinus mucosa of patients withodontogenic maxillary sinusitis associated with thepresence of a foreign body, depending on its duration,can develop, and foreign bodies present in the maxil-lary sinuses cause marked structural reorganization ofthe mucous membrane, usually with the predominanceof hypertrophic and polypous changes.14 The effect ofevaluation of repeated debridement after ESS was re-ported.4 The researchers believed that excessive de-bridement may induce more surgical trauma and causemore facial pain to patients, and, in terms of subjectiverecovery and health care costs, the appropriate extend-ing of postoperative management time and decreasingintervention frequencies will not affect the therapeuticeffect of endoscopic surgery for chronic sinusitis.15

INNATE AND ADAPTIVE IMMUNE SYSTEM INHEALTH AND DISEASE

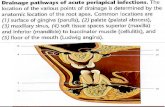

The innate system can occur within a few hours ofcontact with a pathogen that includes complement andother cells (Fig. 1). Neutrophils, T cells, their subdivi-sions, and tissue damage with immune dysfunction,deviation, and chronic inflammation can occur.16 Theadaptive immune response occurs within a few daysand generates immune memory. Microbial mecha-

Figure 1. The immune system in healthand disease (Source: Ref. 16).

Allergy & Rhinology e207

nisms triggered by innate immunity can control mostinfections before the adaptive response, and can resultin harmful effects, and an uncontrolled inflammatoryresponse that is initiated against infection is seen insevere sepsis and its complications.16

Complement is part of the innate immune systemand an important effector mechanism of humoralimmunity. A schematic representation of the classiccomplement cascade that shows the initiation of thepathway by binding of the C1q component of C1binding to the Fc region of an immunoglobulin Gantibody molecule bound to an antigen on the sur-face of a target cell is shown in Fig. 2.17 The sche-matic representation of the alternative pathway maybe formed by one of the other pathways or by non-specific proteolytic cleavage of C3, binds with factorB, which is analogous to C2 (Fig. 3), along with thelate steps of complement activation and the mem-brane attack complex.17

ROLE OF NF-�B RELATED TO INFLAMMATIONActivated neutrophils can upregulate the expression

of many genes, in particular, those that encode cyto-kines and chemokines, and subsequently release thecorresponding proteins. Many of these genes dependon the activation of transcription factors, such as NF-�B, for inducible expression.18 NF-�B activation mayunderlie the action of proinflammatory stimuli towardhuman neutrophil gene expression and add a newfacet to our understanding of neutrophil biology.18

Systemic inflammation subsequent to polytraumacan be connected to polymorphonuclear neutrophils(PMN) dysregulation characterized by reduced NF-�Btranslocation and cytokine expression. NF-�B activa-tion, as well as its downstream regulation of interleu-kin (IL) 8 expression in PMN, can follow majortrauma.19 NF-�B translocation was significantly in-creased on admission and reduced within 6 hours,whereas it increased in the survivors’ group. Thus, aconcomitant initial increase in transcriptional NF-�Bactivity and IL-8 messenger RNA expression was ob-served in the early posttraumatic period, which pre-ceded the downregulation of the innate immune sys-tem.19

The IL-8 concentration in the pulmonary fluid ofpatients with a thoracic trauma is seen as an indicatorfor the occurrence of acute respiratory distress syn-drome (ARDS) because increased levels correlate withthe incidence.20 Discriminating between ARDS andother similar diseases is critically important; however,only a few biomarkers are currently available for diag-nostic purposes.21 Predicting the severity, response totherapy, or outcome of the illness is also important fordeveloping treatment strategies for each patient. Inparallel with progress in understanding the patho-physiology of ARDS, various humoral factors inducedby inflammation and molecules derived from activatedcells or injured tissues have been shown as potentialbiomarkers that may be applied in clinical practice.21 Ina review, the current understanding of the basic patho-physiology of ARDS and associated candidate bio-markers are discussed.21

Cigarette smoke–induced airway inflammationplays a role in the pathogenesis of airway inflamma-

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the classical complementcascade, showing the initiation of the pathway by binding of theC1q component of C1 binding to the Fc region of an immunoglob-ulin G (IgG) antibody molecule bound to an antigen on the surfaceof a target cell. The numbers in bold indicate the sequential stepsthat are involved in the activation of each of the components,leading to the final lytic event carried out by the membrane attackcomplex (MAC). Some sources now use a revised nomenclature forthe fragment of C2, in which C2a is the small fragment that diffuseaway, and C2b is the larger fragment that binds with C4b and actsin the convertase, C4b2b (Source: Refs. 16 and 17).

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the alternative pathway,showing the initiation of the pathway when C3b, which may beformed by one of the other pathways or by nonspecific proteolyticcleavage of C3, binds with factor B, which is analogous to C2.When bound to C3b, B acquires a conformation that allows it to becleaved by the protease D, after which the subsequent steps of thepathway are similar to those of the other two pathways (Source:Refs. 16 and 17).

e208 Fall 2015, Vol. 6, No. 3

tion. Dong et al.22 reviewed resolvin-D1, which ame-liorates inflammatory responses in lung injury, andasthma and inhibited IL-8 and hydrogen peroxideproduction induced by cigarette smoke extract (CSE)attenuating NF-�B activation. Resolvin-D1–attenuatedcigarette smoke extract triggered inhibitor of NK-�Bdegradation and NF-�B/p65 activation dose depend-ently, and inhibited NF-�B DNA binding activity andinhibited cigarette smoke extract induced IL-8 and hy-drogen peroxide production.22

NF-�B also plays an important role in asthma andSLE, including B-cell development, signaling, and cy-tokines, which play a crucial role in the pathogenesis ofSLE and T-cell development.23 The roles of dendriticcells, which can promote tolerance or immunity toantigens, of polymorphisms and of NF-�B linked withSLE were discussed.23

INFLAMMATION, INNATE IMMUNITY, ANDREACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES

The cell-regulated innate immune system often con-tributes to posttraumatic multiple organ dysfunctions.With a cell fraction of 50–60% of all leukocytes, poly-morphonuclear leukocytes have been shown to be keyeffector cells within the innate inflammatory immunereaction, and immunologic abnormalities can provokemultiple organ failure in severely injured patients intwo forms, which follow a biphasic pattern.24 The firstphase is caused by the immune system during a sys-temic inflammatory response, and, in the secondphase, the patient is more susceptible for sepsis due tohost defense failure or immune paralysis.24 Polymor-phonuclear phagocytes and monocytes are the maineffector cells of the innate immune system that areinvolved in organ failure and are controlled by cyto-kines, chemokines, complement factors, and specifictissue signals.25 Major torso trauma can prime andactivate polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) within3–6 hours after injury. Postinjury priming of PMNsmay create an early vulnerable window, during whicha second event activates exuberant PMN cytotoxic su-peroxide anion O2 release, which renders the injuredpatient at high risk for multiple organ failure.26

The impact of trauma on neutrophil function was eval-uated by Hazeldine et al.27 Trauma-induced changes oc-cur related to neutrophil biology, such as posttraumaticcomplications in multiple organ failure and ARDS.This area is gaining considerable interest is the manip-ulation of neutrophil function as a means by which topotentially improve patient outcome.27

Neutrophils play an essential role in the body’s in-nate immune response to infection, and these phago-cytic cells possess an impressive array of microbicidalweapons that can be brought to bear on an invadingpathogen, including a variety of toxic oxygen radical

species and proteolytic enzymes.28 Quinones undergohighly regulated redox reactions in the mitochondria,Golgi apparatus, plasma membrane, and endoplasmicreticulum. Important consequences are the productionof and protection against ROS. The mechanisms bywhich the inflammatory response and ROS productionoccur is also be discussed.28

ASTHMA AND OXIDATIVE STRESSOxidative stress occurs as a result of inflammation

but also from environmental exposure to air pollu-tion.29 There is an important role of oxidative stress,and therapeutic interventions that decrease exposureto environmental ROS or that augment endogenousantioxidant defenses might be beneficial as adjunctivetherapies in patients with asthma.30 Jiang et al.31 inves-tigated the molecular redox mechanisms in allergicasthma and provided a basis for further investigationof oxidative stress in allergic asthma and the signalinginvolved in its pathogenesis. The researchers indicatethat oxidative stress byproduct represents a novelmethod by which asthma disease severity can be mon-itored to attenuate levels of ROS and alleviate oxida-tive stress–induced airway inflammation in patientswith asthma.31

There is a need for interventional studies that pro-vide evidence of a link between oxidative stress anddepression. Patients with asthma and with differentdegrees of severity have been observed. An increase inprocesses of lipid peroxidation, depression of antioxi-dant protection, increase in oxide nitrogen metabolitesin blood serum, and condensate of exhaled air weredetected. These pathologic changes may be consideredas a manifestation of system oxidative stress moreexpressed in the bronchi.32 Asthma and major depres-sive disorder co-occur at higher rates than expected,and alterations in the immune, autonomic nervous,and other key systems are apparent and may contrib-ute to this increased risk of co-occurrence.33 High ratesof major depressive disorder in asthma may resultfrom the stress of chronic illness, the medications usedto treat, or a combination of the two. The high level ofco-occurrence may also reflect dysregulation of certainstress-sensitive biologic processes that contribute to thepathophysiology of both conditions.

Frieri et al.34 recently reviewed asthma, stress, anddepression in women. This review described majorclinical implications of stress, anxiety, and depression,and associated hormonal changes.34 Screening for de-pression and cognitive decline is particularly impor-tant in the geriatric population and in women becauseearly intervention can significantly improve outcomes.Encouraging patients to participate in their own healthcare is an important goal. These interventions can im-pact quality of life and lead to more-effective manage-

Allergy & Rhinology e209

ment. The approach to asthma in the elderly popula-tion is summarized in Fig. 4.

Di Marco et al.35 investigated the correlation betweenpatients’ characteristics, including anxiety and depres-sion, and the level of asthma control evaluated by theasthma control test.35 Patients with poorly controlledasthma were more frequently women, older, obese,and with a worse pulmonary function, with more anx-iety, and/or more depression. The presence of anxietyand depression was associated with a higher healthcare utilization. A better understanding of this associ-ation may have major clinical implications, mainly inpatients with poorly controlled asthma in whom thepresence of anxiety and depression should be investi-gated.35 Wang et al.36 reported the relationship be-tween anxiety and depression, and stated that onlyanxiety is associated with worse asthma control andthat a significant interaction effect of depression andanxiety accounted for lower asthma-related quality-of-life scores.

CHRONIC SINUSITIS AND ASTHMAPATHOGENESIS IN THE ELDERLY

A high prevalence of hyposmia and anosmia canoccur, especially in the elderly, associated with chronicsinusitis. Several different pathophysiologic processes,such as head trauma, aging, autoimmunity, and toxicexposures, can contribute to smell impairment, withdistinct implications concerning prognosis and possi-ble treatment. As allergists, we are most likely to seethis symptom in patients with CRS, and this nowappears to be due more to the mucosal inflammationthan to physical airway obstruction. Several differentpathophysiologic processes, such as head trauma, ag-ing, autoimmunity, and toxic exposures, can contributeto smell impairment, with distinct implications con-cerning prognosis and possible treatment.37

Grainge and Davies38 reviewed epithelial injury andrepair in airway diseases and considered three impor-tant groups of environmental stimuli, such as environ-mental pollution, acetaminophen, viruses, includingrhinovirus; agents that cause barrier disruption (e.g.,house-dust mite allergens). The pathology associatedwith each stimulus was considered, and potential fu-ture treatments that arise from research on their effectswere presented.38 Frieri39 reviewed airway remodel-ing, various inflammatory cells, the role of angiogene-sis, vascular endothelial cell growth factor, respiratorysyncytial virus, and other biomarkers, including ex-haled nitric oxide. Control of allergic asthma by usingimmunomodulation and other strategies were ad-dressed.

Follenweider and Lambertino40 reviewed the epide-miology of asthma in the United States. In 2009 therewere 2.1 million asthma-related emergency depart-ment visits. Emergency department visits lend an op-portunity for providers to identify and intervene in thecare of patients whose asthma is poorly controlled. 40

Asthma is associated with significant morbidity andmortality in the geriatric population, and the diagnosisis frequently missed. Factors that contribute to thisinclude respiratory changes caused by aging, immu-nosenescence, a lack of symptoms, polypharmacy, cli-nician unawareness, and a lack of evidence-basedguidelines for diagnosis and management.40 Madeoet al.41 addressed age-related changes, pathophysiol-ogy, and the role of allergy in elderly patients withasthma. Asthma in the elderly and in younger popu-lations were compared, and a broad set of goals toguide future management driven by a multidisciplineapproach was discussed.41 Age-related changes in pul-monary function, immunity, and perception of symp-toms has rendered the management of asthma in theelderly particularly challenging. Managing these pa-tients is further complicated by the unique issues ofthis population, which include multiple comorbidities,including chronic sinusitis.41

Nassef et al.42 reviewed how fracture risk influencesour decision making in asthma care. The researchersstated the importance of monitoring measures of con-trol in the treatment of asthma and equal vigilance inmonitoring long-term adverse effects, e.g., increasedfracture risk, of the medications used to achieve thatcontrol essential to the total care of patients withasthma.42

ROLE OF VITAMIN D IN CHRONIC SINUSITISAND FRACTURES

A large number of human, animal, and in vitrostudies have indicated that vitamin D3 plays a criti-cal role in inflammatory airway diseases such asasthma, CRS, and allergic rhinitis. Vitamin D3 acts on a

Figure 4. General algorithm, summarizing the multiple issuesthat lead to poorly managed asthma in the geriatric population. Thegoals of a multidisciplinary approach are stated to help guidetreatment (Source: Ref. 41).

e210 Fall 2015, Vol. 6, No. 3

broad range of immune cells involved in the pathogen-esis of these diseases, including T cells, dendritic cells,macrophages, and B cells. In addition, vitamin D3 canalso regulate the functions of a number of nonimmunecells, including epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and smooth-muscle cells.43

Bird et al.44 reviewed the association between sea-sonal variation in vitamin D, postural sway, and falls,and stated the risk and whether postural sway variesseasonally and is associated with serum vitamin D andfalls. Vitamin D levels varied seasonally, peaking insummer. 44 The incidence of falls and injurious fallswere lower in spring, with the highest fall rate at theend of autumn. Postural sway remained stable acrossthe year, whereas vitamin D varied seasonally. Thisstudy provided important evidence for clinicians andresearchers and provided interventions that measuredbalance outcomes across seasons. Frieri and Valluri 45

reviewed, in an earlier study, vitamin D deficiencyas a risk factor for allergic disorders and immunemechanisms. Vitamin D deficiency has been exten-sively reviewed. Vitamin D deficiency was related tothe immune system dysregulation and was positivelycorrelated with the prevalence of allergies, and, afteradjusting the model for age, sex, race, smoking, alco-hol, and educational status, the odds ratio still re-mained significant. There was also a positive correla-tion with allergy subtypes, such as prevalence ofrashes, sneezing, and sinus infections, with low vita-min D.45

TRAUMA AND CYTOKINESSevere trauma can lead to immediate hyperinflam-

matory responses with neutrophil activation, continu-ous interleukin secretion related to IL-6, which caninduce upregulation of further major anti-inflamma-tory cytokines mediators, e.g., IL-1046 which can mark-edly inhibit lymphocyte and phagocytic functions, es-sential for an adequate immune response to invadingmicrobes.46

A recent murine study evaluated the role of intraal-veolar tumor necrosis factor (TNF) � and IL-6 in acombination of skin burn and smoke inhalation inju-ries because this combined trauma is associated withan increased morbidity and mortality compared witheither of these traumas alone.47 The differences be-tween the combined and singular traumas indicatedthat TNF-� plays a role in the immunologic hypore-sponsiveness of the lung and, therefore, in the systemicpathophysiologic pathway that often leads to patientmortality. An inverse correlation between TNF-� andIL-6, both classic markers of inflammation, in the in-traalveolar space was observed.48

SEPSISMeasurements of thioredoxin (Trx), macrophage mi-

gration inhibitory factor (MIF), IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, andprocalcitonin (PCT) in plasma from patients with sys-temic inflammatory stress syndrome (SIRS) and/orsepsis, neutropenic sepsis, healthy volunteers, and pa-tients before esophagectomy were evaluated.49 Plasmalevels of Trx, MIF, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and PCT wereraised in patients with SIRS and/or sepsis. Trx andMIF differed from cytokines and PCT in that levelswere significantly lower in patients with neutropeniacompared with the main SIRS and/or sepsis group.IL-8 and PCT levels were significantly greater in thegroup of patients with neutropenia. The link betweenMIF and Trx highlighted in this study has implicationsfor future investigations into the pathogenesis of SIRSand/or sepsis.49

Sepsis and its sequelae are the leading causes ofdeath among the critically ill in noncoronary intensivecare units (ICU), and, currently, treatment for sepsis islargely supportive, based on fluid resuscitation andadministration of vasopressors and antibiotics. Agreater understanding of the pathophysiology of SIRSand/or sepsis could help identify other effective phar-macotherapies.50 The only pharmacotherapy shown toreduce mortality in sepsis, in a randomized clinicaltrial, was activated protein C.50

GENETIC SUSCEPTIBILITY RELATED TO SEPSISSepsis is a clinical syndrome that occurs in patients

after infection or injury and is a leading cause of mor-bidity and mortality. CD86 polymorphisms have beenassociated with susceptibility to pneumonia-inducedsepsis and may affect gene expression in monocytes.CD86 (B7–2) is expressed on various immune cells andcan play a critical role in immune responses. Geneticpolymorphisms in the CD86 gene may affect the de-velopment of sepsis.51 Polymorphisms in the CD86gene have diverse effects on the pathogenesis of pneu-monia-induced sepsis, in which rs17281995G/C mayincrease the risk of the disease by interfering with thegene expression of CD86 in monocytes, and CD86 poly-morphism affects pneumonia-induced sepsis by de-creasing gene expression in monocytes.52

Genetic variants of the A disintegrin and metallopro-teinase 10 (ADAM10) gene have been shown to beassociated with susceptibility to several inflammatory-related diseases, and the clinical relationship in thedevelopment of sepsis was reviewed in 440 patientswith sepsis. The rs653765 CC genotype in severesepsis showed a higher ADAM10 level compared withhealthy groups, and the rs653765 CC polymorphismhad a strong impact on the production of the ADAM10substrates CX3CL1, IL-6R and TNF-�, and ADAM10might be clinically important and play a critical role in

Allergy & Rhinology e211

the pathogenesis of the development of sepsis, withpotentially important therapeutic implications.53

Sepsis and septic shock frequently cause the admis-sion or complicate the clinical course of critically illpatients admitted in the ICU. Genetic variations thatdisrupt the immune sensing of infectious organismscould affect the ability of the immune system to re-spond to infection and may influence both the geneticpredisposition to infection and the diversity of theclinical presentation of sepsis.54 The aim of a recentstudy was to uncover possible associations betweencommon functional immune gene polymorphisms (ofboth innate and adaptive immunity) and ICU-acquiredsepsis and mortality. Thus, a role that host immunegenetic variations may play in the susceptibility toICU-acquired sepsis and ICU mortality.54

Injury due to trauma can induce immune functionchanges, which lead to both proinflammatory activa-tion known as SIRS and an anti-inflammatory reactionknown as compensatory anti-inflammatory responsesyndrome. SIRS with proven infection is referred to assepsis; however, clinically, it is often difficult to isolatethe microbial inoculum, which makes the differentialdiagnosis between SIRS and sepsis difficult. This dif-ferential diagnosis, in turn, is crucial for further thera-peutic decisions: is an antimicrobial therapy and ag-gressive search for a septic focus with all its adverseeffects necessary, or is a focused symptomatic therapyof the SIRS the adequate treatment concept?55 In mul-tiple trauma situations, both syndromes can developsimultaneously, recently described as mixed antago-nist response syndrome.

Genetic susceptibility can influence immune dys-regulation and can affect sepsis outcomes, as listed byCardoso et al.56 The primary goal of their study was toevaluate the genetic susceptibility that affects sepsisoutcome in 72 patients with sepsis admitted to theICU.56 Seven polymorphisms were genotyped in keyinflammatory response genes in sepsis, includingTNF-�, IL-1�, IL-10, IL-8, Toll-like receptor 4, CXCR1,and CXCR2. The primary finding showed that patientswho were homozygous for the major A allele in IL-10rs1800896 had almost a five times higher chance ofdeveloping septic shock compared with heterozy-gotes.56 Analysis of these data supports the hypothesisthat molecular testing has clinical usefulness to im-prove sepsis prognostic models; therefore, enrichmentof the ICU portfolio by including these biomarkers willaid in the early identification of patients with sepsisand who may develop septic shock.56

The majority of trauma victims end up being man-aged, at least initially, in the emergency department ofhealth care facilities. The initial management of thesepatients is often challenging, requiring precise inter-pretation of symptoms and signs by specialized andexperienced personnel, the utilization of high technol-

ogy imaging modalities for an accurate diagnosis,timely and appropriate resuscitation measures, fre-quent monitoring of response, and timely consultationwith the appropriate specialist.57 The high death rate inthis previous study is multifactorial. The factors re-sponsible for late presentation at the definitive carecenter are multiple. Thus, justify the fact that the publicneeds to be aware of the fact of high velocity trauma oftoday’s world is beyond the comprehension of alterna-tive practitioners.57

According to a recent study, there is limited litera-ture on early unplanned hospital readmissions afteracute traumatic injury, especially at suburban facili-ties.58 A retrospective review of the trauma registry ata suburban, state-designated, level-I academic traumacenter, Stony Brook University School of Medicine,from July 2009 to June 2012, was performed for alladmitted (�24 hours) adult (ages �18 years) traumapatients who were discharged alive, including un-planned readmissions within 30 days of discharge.58

On multivariate analysis, only major comorbidities,hospital length of stay, abdominal abbreviated injuryscore � 3 and discharge to a skilled nursing facility ora subacute facility were significant predictors. Indexadmission to surgical services was associated with asignificantly lower readmission risk. The researchersstated that trauma patients are infrequently readmit-ted, the index admission to a surgical service reducesthe risk of readmission, and earlier medical follow-upshould be considered.58

HAE, TRAUMA, AND STRESSHAE is important for allergists/immunologists, sur-

geons, and otolaryngologists. HAE is a rare autosomaldominant disease most commonly associated withdefects in C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) and mani-fests as recurrent episodes of edema in various bodylocations, atypical symptoms (e.g., ascites), ARDS, andhypovolemic shock have also been reported. Attackscan be triggered by stress and physical trauma. HAEdisease severity is highly variable and may be influ-enced by polymorphisms in other genes and in otherfactors, such as hormones, trauma, stress, and infec-tion. Frazer-Abel and Giclas59 reviewed the importanceof laboratory testing in the diagnosis of HAE, whichhas increased with the advent of new treatments.59

HAE is subdivided into types that can be differentiatedonly by laboratory testing and measurement of C1qlevels, and testing for anti–C1-INH autoantibodies canhelp differentiate acquired angioedema from HAE. Di-agnostic testing for the third hereditary form, calledestrogen-dependent HAE, HAE with normal C1-INH,or HAE type III, still presents challenges, and definitivetesting may have to wait until there is a more-completeunderstanding of this mixed group of patients and

e212 Fall 2015, Vol. 6, No. 3

genetic analysis of C1-INH and other proteins involvedin HAE.59

Pham et al.60 recently reported on successful use ofdaily intravenous infusion of C1 esterase inhibitor con-centrate in the treatment of a patient with HAE andascites, hypovolemic shock, sepsis, and renal and re-spiratory failure. Due to the potential severity of at-tacks, allergists and otolaryngologists must be knowl-edgeable about the recognition and treatment oflaryngeal angioedema. HAE can also be associatedwith some inflammatory and autoimmune disorders,e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus. C1-INH has beenused in some patients with myocardial infarction, isch-emic stroke, sepsis, or capillary leak syndrome, andoff-label supratherapeutic doses without evidence of athrombogenic effect. Thromboembolic events reportedwith C1-INH use are rare, and patients with HAE whoexperienced such events often have underlying throm-boembolic risk factors.61

CONCLUSIONThis review article was a literature search and dis-

cussion of CRS, sinusitis related to trauma, the innateand adaptive immunology NF-�B related to inflamma-tion, sepsis, complement, inflammation, ROS, asthmapathogenesis and asthma in the elderly, oxidativestress, depression, seasonal variation and vitamin D,cytokines, genetic susceptibility related to sepsis, HAErelated to trauma, and stress. Traumatic injury fromblunt objects and falls is also related to asthma, stress,inflammation, anxiety, and depression, which can oc-cur both in traumatic sinusitis and patients withasthma. Stress management both in trauma andasthma is based on the notion that stress causes animmune imbalance in susceptible individuals. Thesevarious topics were clearly linked in this review.

REFERENCES1. Kern RC, Conley DB, Walsh W, et al. Perspectives on the

etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis: An immune barrier hypoth-esis. Am J Rhinol 22:549–559, 2008.

2. Hamilos DL. Chronic rhinosinusitis: Epidemiology and medicalmanagement. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128:693–707; quiz 708–709, 2011.

3. Chaaban MR, Walsh EM, and Woodworth BA. Epidemiologyand differential diagnosis of nasal polyps. Am J Rhinol Allergy27:473–478, 2013.

4. Halawi AM, Smith SS, and Chandra RK. Chronic rhinosinusitis:Epidemiology and cost. Allergy Asthma Proc 34:328–334, 2013.

5. Tan BK, Kern RC, Schleimer RP, and Schwartz BS. Chronicrhinosinusitis: The unrecognized epidemic. Am J Respir CritCare Med 188:1275–1277, 2013.

6. Tan BK, Schleimer RP, and Kern RC. Perspectives on the etiol-ogy of chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol HeadNeck Surg 18:21–26, 2010.

7. Settipane RA, Peters AT, and Chandra R. Chronic rhinosinus-itis. Chapter 4. Am J Rhinol Allergy 27(suppl. 1):S11–S15, 2013.

8. Asaka D, Nakayama T, Hama T, et al. Risk factors for compli-cations of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis.Am J Rhinol Allergy 26:61–64, 2012.

9. Frieri M. Asthma linked with rhinosinusitis: An extensive re-view. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 5:41–49,2014.

10. Karosi T, Sziklai I, and Csomor P. Low-frequency ultrasoundfor biofilm disruption in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal pol-yposis: In vitro pilot study. Laryngoscope 123:17–23, 2013.

11. Madeo J, and Frieri M. Bacterial biofilms and chronic rhinosi-nusitis. Allergy Asthma Proc 34:335–341, 2013.

12. Yelverton JC, Jackson P, and Schmidt RS. Chronic rhinosinusitisin patients requiring surgical repair of a midface fracture. EarNose Throat J 93:E26–E28, 2014.

13. Lakouichmi M, Baïzri H, Mouhsine A, et al. An unusual intra-cranial metallic foreign bodies and panhypopituitarism. PanAfr Med J 19:33, 2014.

14. Vishniakov VV, Makarova NV, and Pashovkina OV. Changes inthe mucous membrane of the patients with chronic maxillarysinusitis caused by foreign bodies [in Russian with Englishabstract]. Vestn Otorinolaringol (1):12–14, 2014.

15. Shi L, Feng Y, Cui W, et al. Effect evaluation of repeateddebridement after endoscopic sinus surgery. Int J Clin Exp Med8:928–933, 2015.

16. Bellanti, JA. The Immune System in Health and Disease. Immu-nology IV. ICARE Press, 2012.

17. Berger M. Complement. Chapter 4. In Immunology IV. ClinicalApplications in Health and Disease. Bellanti JA (Ed). Bethesda:I Care Press, 101–129, 2012.

18. McDonald PP, Bald A, and Cassatella MA. Activation of theNF-kappaB pathway by inflammatory stimuli in human neu-trophils. Blood 89:3421–3433, 1997.

19. Stegmaier JC, Kirchhoff C, and Bogner V. Dynamics of neutro-philic NF-kB translocation in relation to IL-8 mRNA expressionafter major trauma. Inflamm Res 57:547–554, 2008.

20. Bouros D, Alexandrakis MG, Antoniou KM, et al. The clinicalsignificance of serum and bronchoalveolar lavage inflammatorycytokines in patients at risk for acute respiratory distress syn-drome. BMC Pulm Med 4:6, 2004.

21. Fujishima S. Pathophysiology and biomarkers of acute respira-tory distress syndrome. J Intensive Care 2:32, 2014.

22. Dong J, Zhang M, Liao Z, et al. Resolvin-D1 inhibits interleu-kin-8 and hydrogen peroxide production induced by cigarettesmoke extract in 16HBE cells via attenuating NF-�B activation.Chin Med J (Engl) 127:511–517, 2014.

23. Zubair A, and Frieri M. NF-�B and systemic lupus erythema-tosus: Examining the link. J Nephrol 26:953–959, 2013.

24. DeLong WG Jr, and Born CT. Cytokines in patients with poly-trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res (422):57–65, 2004.

25. Hietbrink F, Koenderman L, Rijkers GT, and Leenen L. Trauma:The role of the innate immune system. World J Emerg Surg 1:15,2006.

26. Botha AJ, Moore FA, Moore EE, et al. Postinjury neutrophilpriming and activation: An early vulnerable window. Surgery118:358–364, 1995.

27. Hazeldine J, Hampson P, Lord JM. The impact of trauma onneutrophil function. Injury 45:1824–1833, 2014.

28. Swain SD, Rohn TT, and Quinn MT. Neutrophil priming in hostdefense: Role of oxidants as priming agents. Antioxid RedoxSignal 4:69–83, 2002.

29. Madeo J, Zubair A, and Marianne F. A review on the role ofquinones in renal disorders. Springerplus 2:139, 2013.

30. Syed S, Zubair A, and Frieri M. Immune response to nanoma-terials: Implications for medicine and literature review. CurrAllergy Asthma Rep 13:50–57, 2013.

31. Jiang L, Diaz PT, Best TM, et al. Molecular characterization ofredox mechanisms in allergic asthma. Ann Allergy AsthmaImmunol 113:137–142, 2014.

Allergy & Rhinology e213

32. Pobed’onna HP. Antioxidant protection, metabolites of nitro-gen oxide on the forming of oxidative stress in patients withbronchial asthma [in Ukrainian with English abstract]. LikSprava Jul-Sep:36–40, 2005.

33. Van Lieshout RJ, Bienenstock J, and MacQueen GM. A reviewof candidate pathways underlying the association betweenasthma and major depressive disorder. Psychosom Med 71:187–195, 2009.

34. Frieri M, O’Connor M, and Nassef M. Asthma, stress and de-pression in women. Allergy Asthma Proc 36:256–261, 2015.

35. Di Marco F, Verga M, Santus P, et al. Close correlation betweenanxiety, depression, and asthma control. Respir Med 104:22–28,2010.

36. Wang G, Wang L, Szczepaniak WS, et al. Psychological status inuncontrolled asthma is not related to airway hyperresponsive-ness. J Asthma 47:93–99, 2010.

37. Gaines AD. Anosmia and hyposmia. Allergy Asthma Proc 31:185–189, 2010.

38. Grainge CL, and Davies DE. Epithelial injury and repair inairways diseases. Chest 144:1906–1912, 2013.

39. Frieri M. Advances in the understanding of allergic asthma.Allergy Asthma Proc 28:614–619, 2007.

40. Follenweider LM, and Lambertino A. Epidemiology of asthmain the United States. Nurs Clin North Am 48:1–10, 2013.

41. Madeo J, Li Z, and Frieri M. Asthma in the geriatric population.Allergy Asthma Proc 34:427–433, 2013.

42. Nassef M, Temprano J, Frieri M, and Rossman S. Should frac-ture risk influence our decisionmaking in asthma care. AnnAllergy Asthma Immunol 106:164–167, 2011.

43. Yawn J, Lawrence LA, Carroll WW, Mulligan JK. Vitamin D forthe treatment of respiratory diseases: Is it the end or just thebeginning? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 148:326–337, 2015.

44. Bird ML, Hill KD, Robertson I, et al. The association betweenseasonal variation in vitamin D, postural sway, and falls risk:An observational cohort study. J Aging Res 2013:751310, 2013.

45. Frieri M, and Valluri A. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor forallergic disorders and immune mechanisms. Allergy AsthmaProc 32:438–444, 2011.

46. Bouros D, Alexandrakis MG, Antoniou KM, et al. The clinicalsignificance of serum and bronchoalveolar lavage inflammatorycytokines in patients at risk for acute respiratory distress syn-drome. BMC Pulm Med 4:6, 2004.

47. Neidhardt R, Keel M, Steckholzer U, et al. Relationship of interleu-kin-10 plasma levels to severity of injury and clinical outcome ininjured patients. J Trauma 42:863–870; discussion 870–871, 1997.

48. Stromps JP, Fuchs P, Demir E, et al. Intraalveolar TNF-� incombined burn and inhalation injury compared with intraal-veolar interleukin-6. J Burn Care Res 36:e55–e61, 2015.

49. Leaver SK, MacCallum NS, Pingle V, et al. Increased plasmathioredoxin levels in patients with sepsis: Positive associationwith macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Intensive CareMed 36:336–341, 2010.

50. Bernard GR, Ely EW, Wright TJ, et al. Safety and dose relation-ship of recombinant human activated protein C for coagulopa-thy in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 29:2051–2059, 2001.

51. Wang C, Gui Q, and Zhang K. Functional polymorphisms inCD86 gene are associated with susceptibility to pneumonia-induced sepsis. APMIS 123:433–438, 2015.

52. Song H, Tang L, Xu M, et al. CD86 polymorphism affectspneumonia-induced sepsis by decreasing gene expression inmonocytes. Inflammation 38:879–885, 2015.

53. Cui L, Gao Y, Xie Y, et al. An ADAM10 promoter polymor-phism is a functional variant in severe sepsis patients andconfers susceptibility to the development of sepsis. Crit Care19:73, 2015.

54. Kompoti M, Michopoulos A, Michalia M, et al. Genetic poly-morphisms of innate and adaptive immunity as predictors ofoutcome in critically ill patients. Immunobiology 220:414–421,2015.

55. Novotny AR, Reim D, Assfalg V, et al. Mixed antagonist re-sponse and sepsis severity dependent dysbalance of pro- andanti-inflammatory responses at the onset of postoperative sep-sis. Immunobiology 217:616–621, 2012.

56. Cardoso CP, de Oliveira AJ, Botoni FA, et al. Interleukin-10rs2227307 and CXCR2 rs1126579 polymorphisms modulate thepredisposition to septic shock. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 110:453–460, 2015.

57. Ugare GU, Bassey IE, Udosen JE, et al. Trauma death in aresource constrained setting: Mechanisms and contributory fac-tors, the result of analysing 147 cases. Niger J Clin Pract 17:397–402, 2014.

58. Copertino LM, McCormack JE, Rutigliano DN, et al. Early un-planned hospital readmission after acute traumatic injury: Theexperience at a state-designated level-I trauma center. Am JSurg 209:268–273, 2015.

59. Frazer-Abel A, and Giclas PC. Update on laboratory tests for thediagnosis and differentiation of hereditary angioedema andacquired angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc 32(suppl 1.):S17–S21, 2011.

60. Pham H, Santucci S, and Yang WH. Successful use of dailyintravenous infusion of C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate in thetreatment of a hereditary angioedema patient with ascites, hy-povolemic shock, sepsis, renal and respiratory failure. AllergyAsthma Clin Immunol 10:62, 2014.

61. Crowther M, Bauer KA, and Kaplan AP. The thrombogenicityof C1 esterase inhibitor (human): Review of the evidence. Al-lergy Asthma Proc 35:444–453, 2014. e

e214 Fall 2015, Vol. 6, No. 3