Rethinking Humanitarianism: Adapting to 21 st Century ... · Last, but certainly not least, ......

Transcript of Rethinking Humanitarianism: Adapting to 21 st Century ... · Last, but certainly not least, ......

-

Rethinking Humanitarianism:Adapting to 21st Century Challenges

NOVEMBER 2012Jérémie Labbé

I N T E RNAT I ONA L P E AC E I N S T I T U T E

-

Cover Photo: © Jérémie Labbé, 2006.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in

this paper represent those of the

author and not necessarily those of

IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a

wide range of perspectives in the

pursuit of a well-informed debate on

critical policies and issues in interna-

tional affairs.

IPI Publications

Adam Lupel, Editor and Senior FellowMarie O’Reilly, Publications Officer

Suggested Citation:

Jérémie Labbé, “Rethinking

Humanitarianism: Adapting to 21st

Century Challenges,” New York:

International Peace Institute,

November 2012.

© by International Peace Institute,

2012

All Rights Reserved

www.ipinst.org

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JÉRÉMIE LABBÉ is Senior Policy Analyst at the

International Peace Institute (IPI) working on humanitarian

affairs. Before joining IPI, he worked for several years with

the International Committee of the Red Cross both in its

headquarters in Geneva and in field missions in India,

Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, Madagascar, and Iraq. His work with the

ICRC primarily focused on issues of protection and interna-

tional humanitarian law.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to all the humanitarian practitioners

and policymakers met during the course of this study that

helped to develop the understanding of the modern

humanitarian system and to shape the present paper.

Special thanks go to Dirk Salomons, Daniel Pfister, François

Grünewald, and Pierre Dorbes for reviewing an earlier draft

of this paper and sharing their perspectives on the

evolution of the global humanitarian system. Last, but

certainly not least, nothing would have been possible

without the regular support and guidance of Francesco

Mancini, IPI Senior Director of Research, the expert work of

Adam Lupel and Marie O’Reilly in editing and producing

this publication, and the skills of Chris Perry in designing

the charts used in the report.

IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors,

whose contributions make publications like this one

possible.

-

CONTENTS

Acronyms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Defining the Boundaries of theHumanitarian Enterprise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Today’s Challenges and Their Implications . . . . . . . . 8

A Six-Point Agenda for Adaptation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Managing Tensions: Key Questions forthe Future of Humanitarianism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

-

Acronyms

ASEAN Association of South-East Asian Nations

CBHA Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies

CERF Central Emergency Response Fund

ECHO European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department

ECOSOC United Nations Economic and Social Council

ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States

ERC Emergency Relief Coordinator

GHD Global Humanitarian Donorship

HC United Nations Humanitarian Coordinator

IASC Inter-Agency Standing Committee

ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross

ICT Information and Communication Technologies

IFRC International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

MSF Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders

OCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

OECD-DAC Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development AssistanceCommittee

OIC Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

RC United Nations Resident Coordinator

UNAMA United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNISDR United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction

UNRWA United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees

WFP World Food Programme

iii

-

1

Executive Summary

The modern international humanitarian system,defined as much by similarities and shared values asby differences and competition among its members,is being tested like never before. The cumulativeeffects of population growth, climate change,increased resource scarcity, rising inequalities,economic and geopolitical shifts, the changingnature of violence, and rapid technological deve -lopments are presenting the humanitarian systemwith four broad challenges:• an increasing humanitarian caseload; • the changing nature of crises;• a renewed assertiveness of host states; and• finite financial resources.While the humanitarian system remains a

relatively heterogeneous lot, with different actorsproposing different solutions, a six-point agendafor adaptation has become apparent. According tothis conventional wisdom, the humanitariansystem must:1) anticipate the risks;2) strengthen local capacities and resilience;3) develop new partnerships;4) enlarge the funding base and use it moreeffectively;

5) enhance coordination, leadership, accounta-bility, and professionalization; and

6) make innovations and leverage new technolo-gies.

This ambitious agenda might well allow thehumanitarian system to better face some oftomorrow’s challenges, but it is not withouttensions. What these tensions have in common is agrowing disconnect between the expandingambitions of the international humanitarian systemand some of its fundamental premises: the univer-sality of the undertaking, the integrity of its princi-ples, and the value of increased coherence andcoordination. To resolve some of the deeply rooted tensions

inherent in this ambitious agenda, humanitarian

actors must undertake a thorough and honest self-examination: • Are the foundations of the modern humani-tarian system truly universal? How can thesystem adapt to a changing internationallandscape and open up to actors who did notparticipate in its development—actors whomight have different views and practices?

• Are humanitarian principles always relevant? Isthe systematic reference to humanitarianprinciples undermining them, given arecurrent lack of respect? Could a sparser butmore faithful use of principles, adapted to thecontext, be envisaged?

• Is the quest for ever greater coherence andcoordination always a good thing? Could thefragmentation of the system be valued as astrength, given the comparative advantages ofits various components?

This exercise in self-reflection may reveal theemergence of a sort of “global welfare system,” moreambitious and far-reaching than the traditionalunderstanding of humanitarian action. This newundertaking would benefit from redefining its rulesand theoretical foundations to be in tune with itsbroader objectives. And while this shift might bringmore consistency by easing some of the currenttensions—especially those linked to the humani-tarian principles—humanitarian actors will have tomake the hard choice between a global, holisticapproach and a more limited, but still badly needed,form of humanitarianism.

Introduction

Some of the most important organizations presentlyresponsible for preventing, preparing for andresponding to the sorts of humanitarian challengesthat are anticipated in the future are failing to do so.1

This bleak assessment of the humanitarian systemin 2007 provided a much needed wake-up call. Fiveyears later, this call has apparently been heard.Humanitarian actors are increasingly aware of theneed to adapt to the twenty-first-centurychallenges, and literature is abundant on the

1 Humanitarian Futures Programme, “Dimensions of Crisis Impacts: Humanitarian Needs by 2015,” a report prepared for the UK Department for InternationalDevelopment, January 2007, p. 52, available at www.hapinternational.org/pool/files/dimensions-of-crisis.pdf .

www.hapinternational.org/pool/files/dimensions-of-crisis.pdf

-

2 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

required changes.2 The question remains, however,whether the measures currently being consideredwill successfully meet tomorrow’s challenges.The aim of this report is not so much to anticipate

the nature and scale of future humanitarian needs;other studies have done that with brio. Instead, itexamines the type of responses being consideredwithin the humanitarian system to adapt to thischanging world. It aims to generate discussion onsome of the unavoidable tensions that such anambitious undertaking is raising. No singlehumanitarian actor—or group of actors—will beable to address the numerous challenges aheadalone. The diverse skills and approaches availablewithin, but also outside, the humanitarian systemwill all need to be associated with the effort, whilemanaging the tensions that such a collective effortinevitably creates.After sketching out the ill-defined boundaries of

the humanitarian system to explain its origins anddefine the scope of the enterprise, this reportfocuses on the challenges faced by the system todayand identifies the outline of a shared adaptationstrategy. The last section reflects upon some of thetensions inherent in this ambitious program andraises key questions about the future of humanitar-ianism.

Defining the Boundaries ofthe Humanitarian Enterprise

The international humanitarian system evolved. Itwas never designed, and like most products ofevolution, it has its anomalies, redundancies, ineffi-ciencies, and components evolved for one task beingadapted to another.3

If one asks a randomly chosen person to definehumanitarian aid, the person is likely to define it asactions aimed to save lives and alleviate suffering,reflecting notions of charity, philanthropy, oraltruism shared by most cultures and religions sincethe dawn of time. If one prods a little further, our

random respondent would probably add thathumanitarian aid is generally deployed in conflictsand natural disasters around the world. Yet, as humanitarian aid has become more

institutionalized over the years, so has its defini-tion. According to the Development AssistanceCommittee of the Organisation for EconomicCooperation and Development (OECD-DAC)—which brings together the main international aiddonors—“humanitarian aid is assistance designedto save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain andprotect human dignity during and in the aftermathof emergencies. To be classified as humanitarian,aid should be consistent with the humanitarianprinciples of humanity, impartiality, neutrality andindependence.”4

Interestingly, three elements stand out that canfurther clarify the constitutive characteristics ofhumanitarian aid:• As our imaginary interviewee replied, humani-tarian aid aims to save lives and alleviatesuffering, but (s)he apparently oversaw the lessobvious objective of upholding human dignity.In other words, humanitarian aid, throughassistance and the growing spectrum of protec-tion activities, aims primarily to tackle theeffects on human beings of extraordinarycircumstances.

• Humanitarian aid is a short-term endeavorcarried out “during and in the aftermath ofemergencies.” As provocative as it may sound,once the Band-Aid is applied to an openwound, and a minimum follow-up isundertaken to ensure it does not infect, thework of humanitarians is done.

• Finally, humanitarian aid is informed by a set ofhumanitarian principles that, according to thedefinition above, distinguishes it from otherforms of aid: it should be motivated by the soleaim of helping other humans affected bydisasters (humanity), exclusively based on

2 This includes but is not limited to: Edmund Cairns, “Crises in a New World Order: Challenging the Humanitarian Project,” Oxford, UK: Oxfam International, 2012;Lord Paddy Ashdown (Chair), “Humanitarian Emergency Response Review,” study commissioned by the UK Department for International Development, London:HERR, March 2011; Feinstein International Center/Humanitarian Futures Programme (FIC/HFP), “Humanitarian Horizons: A Practitioner’s Guide to the Future,”Medford, MA: 2010; Benedict Dempsey and Amelia B. Kyazze, “At a Crossroads: Humanitarianism for the Next Decade,” London: International Save the ChildrenAlliance, 2010; Kirsten Gelsdorf, “Global Challenges and their Impact on International Humanitarian Action,” New York: UN OCHA, 2010; Alain Boinet andBenoît Miribel, “Analyses et Propositions sur l’Action Humanitaire dans les Situations de Crise et Post-Crise,” study commissioned by the French Ministry ofForeign Affairs, Paris, 2010; and Tanja Schuemer-Cross and Ben Heaven Taylor, “The Right to Survive: The Humanitarian Challenge for the Twenty-First Century,”Oxford, UK: Oxfam International, 2009.

3 Peter Walker and Daniel Maxwell, Shaping the Humanitarian World (New York: Routledge, 2009), p. 2. 4 OECD, DAC Statistical Reporting Directives, OECD Doc. DCD/DAC(2010)40/REV1, November 12, 2010, para. 184.

-

people’s needs and without any furtherdiscrimination (impartiality), without favoringany side in a conflict or other dispute where aidis deployed (neutrality), and free from anyeconomic, political, or military interests atstake (independence).

While most would agree on these core elementsof humanitarian aid, more nuance is needed, asdisagreements have always existed on theirinterpretation and operational implementation. For instance, there have been many debates on

the meaning of the neutrality of humanitarianaction, particularly on whether this neutralityimplies non-engagement in any type of controversy.Detractors have questioned in particular whether itis morally justified to remain neutral and not totake position when confronting mass atrocities,such as during the Holocaust, the Biafran War, orthe Rwandan Genocide.5 Likewise, it is not entirelycorrect to assert that humanitarian aid aims totackle the effects of crises only. Indeed, it iscommonly agreed that protection—defined as all

activities aimed at ensuring respect for the rights ofthe individual in accordance with internationalhuman rights, humanitarian, and refugee law6—includes promoting lasting changes in the politicaland socioeconomic environment in order todiminish the likelihood of recurrence of violations.In other words, protection incidentally addressescauses of human suffering through longer-termactions, such as training of armed forces or groupson international norms and standards, advocatingfor the enactment of international law in domesticlegislation, and strengthening of the domesticjustice system. However, attempts to define humanitarian aid are

further complicated by the growing tendency, asnoted by Walker and Maxwell, to place “muchgreater emphasis in humanitarian action on dealingwith the underlying causes of crisis, in addition to(or in some cases, rather than) dealing with effectsof crises on human populations.”7 In effect, somehumanitarian organizations have grown uncom -fortable with addressing only the consequences and

Jérémie Labbé 3

5 Philip Gourevitch, “Alms Dealers: Can You Provide Humanitarian Aid Without Facilitating Conflicts?” The New Yorker, October 11, 2010, p. 102, and David Rieff,A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002). For an in-depth analysis of ethical questions raised by relief operationsfollowing the Rwandan Genocide, see Fiona Terry, Condemned to Repeat? The Paradox of Humanitarian Action (New York: Cornell University Press, 2002), p. 155ff.

6 Sylvie Giossi Caverzasio, ed., Strengthening Protection in War: A Search for Professional Standards (Geneva: ICRC, 2001). 7 Walker and Maxwell, Shaping the Humanitarian World, p. 141 (original emphasis).

International Recognition and Utility of the Humanitarian PrinciplesThe humanitarian principles were first given international recognition by the twentieth International Conference ofthe Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in 1965, along with three other Red Cross–specific principles: voluntaryservice, unity, and universality.UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182 of December 19, 1991, consecrated the principles of humanity, neutrality,

and impartiality, while independence was officially recognized only in 2003 in Resolution 58/114. These principles arealso mentioned in a number of documents that set standards for the humanitarian sector, such as the 1986 Statutes ofthe Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, the 1994 Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and RedCrescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief, the 2003 Good Humanitarian Donorship principles, and the 2008European Consensus on Humanitarian Aid.These principles are central to the humanitarian undertaking and represent a key characteristic of humanitarian aid.

However, as Jean Pictet argued in his commentary on the fundamental principles of the Red Cross, they do not all havethe same importance.* Humanitarian principles have a hierarchical order and an internal logic or, in other words,different domains of utility. Humanity and impartiality—to which Pictet referred to as “substantive principles”—are atthe core of the humanitarian ethos: humanitarian aid must be motivated by the sole aim of helping other humansproportionally to their needs and without any discrimination. Independence and neutrality—referred to by Pictet as“derived principles”—are means that make this ideal possible, especially in situations of conflict. Indeed, independ-ence and neutrality are field-tested tools that make access to populations in need acceptable to the parties to a conflict.They are guarantees that humanitarian aid does not serve ulterior political, economic, or military motives, or aim tobenefit the opposing party.*Jean Pictet, “The Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross: Commentary,” Geneva: ICRC, 1979.

-

not also the root causes of both man-made andnatural disasters. The termination of an emergencydoes not mean that its underlying reasons haveceased to exist. Hence, humanitarian actors haveincreasingly engaged in longer-term reconstructionand development following humanitarian crises.This shift brought about the emergence in the lastdecade of a so-called “new humanitarianism”8 thatseeks to address not only symptoms but causes ofconflicts by building better societies throughhumanitarian action, development, goodgovernance, human rights, and, if required, military“humanitarian intervention.” Such an approachopenly collides with the principles of independenceand neutrality, as its proponents acknowledge theneed to align with other approaches directedtoward the same goals, including political ones.Jean-Hervé Bradol, former president of MédecinsSans Frontières (MSF, or Doctors WithoutBorders), even argued that this “alliance” withpolitical interests for the “greater good” is at oddswith the very purpose of humanitarian aid,illustrating the wide diversity of views on whathumanitarian aid truly is.9

A HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF HUMANITARIAN AID

Charity and philanthropy have been embodied forcenturies in most cultures and religions, and earlyexamples abound of actions by states and religiousinstitutions or orders to alleviate human sufferingin situations of man-made or natural disasters.10However, the modern humanitarian system can betraced back to the Battle of Solferino in 1859 thatled to the creation of the International Committeeof the Red Cross (ICRC) by Henri Dunant and,later, of the broader Red Cross and Red CrescentMovement (hereafter, the Red Cross Movement).The ICRC is closely related to the birth of interna-tional humanitarian law and is also at the origin ofthe humanitarian principles of humanity,

impartiality, neutrality, and independence.11 Ineffect, the development of the Red Cross Movementmarked the emergence of organized nongovern-mental humanitarian action.International humanitarian nongovernmental

organizations (NGOs) appeared throughout thetwentieth century and, as noted by Elizabeth Ferris,“all of the major international NGOs—from CAREInternational to Oxfam—first started out byproviding assistance in times of war.”12 Save theChildren was created in 1919 to pressure the Britishgovernment to lift its blockade against Germanyand Austria-Hungary; the Second World Warprompted the creation of Oxfam and CARE; theBiafran War in Nigeria in the late 1960s saw thebirth of the “without borders” movement, bestillustrated by the French organization MSF; andsuccessive Cold War conflicts in the 1970s and1980s triggered the creation of a new generation ofNGOs such as Action Contre la Faim (ActionAgainst Hunger) in France, Merlin in the UnitedKingdom, and GOAL in Ireland.13

The picture would not be complete withoutmentioning the entrance after the Second WorldWar of a new major player on the then nascenthumanitarian scene: the United Nations (UN) andits different agencies. Reflecting to some extent thedevelopment of NGOs, three of the five UNagencies having a humanitarian mandate werecreated out of concerns for people affected by thescourge of conflict or oppression: the UN Children’sFund (UNICEF, 1946) was originally created torespond to the needs of Europe’s war-affectedchildren, while the UN Relief and Works Agencyfor Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA, 1950) and theUN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR,1951) were established for refugees fleeing conflictand persecution.14

By contrast, until the 1980s, disaster responseremained mostly the responsibility of the affected

4 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

8 Fiona Fox, “New Humanitarianism: Does it Provide a Moral Banner for the 21st Century?” Disasters 25, No. 4 (December 2001): 275-289; Joanna Macrae, ed.,“The New Humanitarianisms: A Review of Trends in Global Humanitarian Action,” London: Overseas Development Institute, April 2002.

9 Jean-Hervé Bradol, “The Sacrificial International Order and Humanitarian Action,” in In the Shadows of “Just Wars”: Violence, Politics and Humanitarian Action,edited by Fabrice Weissman (London: Médecins Sans Frontières, 2004), p. 21.

10 Walker and Maxwell, Shaping the Humanitarian World, p. 13ff.11 See the text box on page 3 of this report.12 Elizabeth G. Ferris, The Politics of Protection: The Limits of Humanitarian Action (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2011), p. 99. 13 See Walker and Maxwell, Shaping the Humanitarian World, p. 117ff., and Philippe Ryfman, “Non-Governmental Organizations: An Indispensable Player of

Humanitarian Aid,” International Review of the Red Cross 89, No. 865 (March 2007): 21-45.14 The two other UN agencies with a humanitarian mandate are OCHA (technically, an office of the UN Secretariat), whose predecessor, the UN Disaster Relief

Organization, was created in 1972 for disaster response, and the World Food Programme, which was established in 1961 to deliver food aid in emergencies regard-less of their nature. For further details on the development of the UN humanitarian system, see Walker and Maxwell, Shaping the Humanitarian World, p. 33ff.

-

state, often supported by direct bilateral aid fromother governments, despite early attempts tointernationalize the system through the creation ofthe League of the Red Cross in 1919 and of theLeague of Nations’ International Relief Union in1927.15 According to Paul Harvey, this central roleof the affected state in disaster response “was afunction of the connections between relief and thewider sphere of development aid assistance, whichhas largely been constructed as a ‘state-centered’endeavour.”16 This changed with the end of the ColdWar, which saw a marked preference among donorstates to channel their funding through interna-tional organizations and NGOs, due in part to agrowing distrust in the capacities of receiving statesto efficiently handle foreign aid. This shift inattitude by donor governments contributed to theboom of the nongovernmental humanitariansector, which has become increasingly involved indisaster relief assistance.In a nutshell, the modern international humani-

tarian system, characterized by the growinginvolvement of international organizations andNGOs, is a compilation of largely Western govern-mental and individual initiatives over more than acentury that were created primarily in reaction toconflict. Natural disaster relief took a more centralstage in the last two decades as donor governmentschanged their aid policy and started channelingfunding through international and nongovern-mental relief organizations, rather than throughbilateral aid. Newly available funding in turnprompted the proliferation of new NGOs joiningwhat can now be described as a multibillion-dollarhumanitarian enterprise, whose financial weighthas been multiplied by ten in the last twenty years.17

MAPPING THE HUMANITARIAN SYSTEM

At the frontline of crisis response are the affectedcommunities themselves—supported by local civil-society organizations, including religious institu-tions—and local and national authorities, includingthe national military. Nonstate armed groups canalso play a role in emergency relief when theyexercise some degree of control over a population.

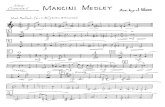

It is difficult to quantify the share of local andnational response to a given crisis in the overallhumanitarian response. In part this is because thereis no consistent and systematic financial reportingof local and national response, but it is also becausesome elements, such as local coping mechanisms,are unquantifiable. Yet, the following chartborrowed from the 2011 Global HumanitarianAssistance Report (GHA Report) gives an idea ofthe relatively marginal importance of formalhumanitarian assistance compared to the largearray of other sources of relief funds (figure 1).18 Itrepresents total funding flows to the top twentyrecipient countries in 2009 and illustrates how the$8.1 billion of humanitarian assistance is dwarfedby other flows that also indirectly contribute toemergency relief, such as remittances fromdiasporas and domestic revenues of the affectedstates.The international humanitarian system comple-

ments the initial emergency response put in place atlocal and national level, and generally comes inafter it. The traditional elements of the modern

Jérémie Labbé 5

Figure 1. Formal humanitarian assistance inperspective

15 The League of the Red Cross later became the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).16 Paul Harvey, “Towards Good Humanitarian Government: The Role of the Affected States in Disaster Response,” London: Overseas Development Institute, 2009,

p. 5.17 Michaël Neuman, “The Shared Interests Which Make Humanitarianism Possible,” Humanitarian Aid on the Move, Newsletter No. 9 (March 2012): 2-4.18 Development Initiatives, “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2011,” Somerset, UK: 2011, available at www.globalhumanitarianassistance.org/report/gha-

report-2011 . Development Initiatives is an organization that monitors development and humanitarian funding flows in order to improve aid effectiveness.

www.globalhumanitarianassistance.org/report/gha-report-2011www.globalhumanitarianassistance.org/report/gha-report-2011

-

humanitarian system are the following:• Donor governments, along with the EuropeanCommission’s humanitarian aid department(ECHO). Traditional donor governments aremostly Western and are gathered within theOECD-DAC, representing the bulk of globalhumanitarian funding. Although nontradi-tional donors—notably Middle Easterncountries—are playing an increasingly signifi-cant role, as we shall see later in this paper, thepolitics of humanitarian action remain shapedmostly by OECD-DAC members.

• United Nations agencies and offices and otherintergovernmental organizations (such as theInternational Organization for Migration). TheUN Office for the Coordination ofHumanitarian Affairs (OCHA) plays a key rolein coordinating the various operationalcomponents of the humanitarian system. UNagencies are gathered in the Inter-AgencyStanding Committee (IASC), chaired by thehead of OCHA in its capacity as emergencyrelief coordinator, in which the Red CrossMovement and some NGO platforms are alsorepresented as standing invitees.

• The constitutive entities of the Red CrossMovement—the ICRC, the IFRC, and thegalaxy of 187 National Red Cross or RedCrescent Societies.

• International humanitarian NGOs, which areas diverse as they are numerous. A team ofresearchers recently counted 4,400 NGOscarrying out humanitarian activities on anongoing basis,19 which does not take intoaccount the thousands of smaller developmentNGOs that engage in relief activities when adisaster strikes or those established in reactionto a particular event.20

Beyond these traditional actors of the interna-tional humanitarian system, other actors—oftenreferred to as “nontraditional” actors—increasinglycontribute to international relief activities: foreign

militaries, private military and security companies,corporations, private foundations, diasporas, etc. Itis arguable that these actors have alwayscontributed to relief operations but were placedoutside of the system by its main protagonists, asthe latter continuously attempted to better definethemselves. As John Borton writes, “a strikingfeature of the humanitarian system…is the contin-uing lack of clarity as to what the ‘humanitariansystem’ actually consists of and where itsboundaries lie.”21

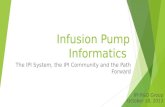

It might be useful here to think about thehumanitarian galaxy as made up of two differentsystems. On the one hand, as depicted in figure 2below, there is what could be called the formal, orinstitutional, humanitarian system. The formalsystem—the focus of the present paper—consists ofmostly Western actors whose raison d’être ishumanitarian and who are linked together byestablished codes, shared principles and jargon, andcommon mechanisms and procedures. Over thelast two decades, the formal system has becomeincreasingly institutionalized and centralized underUN leadership for the sake of improved coherenceand coordination.22 On the other hand, there is aninformal humanitarian system, constituted by theaffected communities and so-called nontraditionalactors coming to their succor, and driven bydifferent modes of action and objectives, be theycharitable, economic, or political. Some of theseactors—such as small national NGOs and thenational authorities of the host state—are increas-ingly being integrated into the formal humanitariansystem, which has grown more aware of the need tobetter work with them, as discussed later in thisreport. One of the difficulties in defining the humani-

tarian system—an exercise usually carried out bymembers of the formal humanitarian system—isthat it virtually encompasses anybody extending ahelping hand to people affected by crises. Anotherdifficulty is linked to the long-standing antagonismand increasing overlaps between humanitarianism

6 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

19 ALNAP, “The State of the Humanitarian System: 2012 Edition,” London: Overseas Development Institute, July 2012, p. 28. It is worth noting that the NGO sectorremains dominated by five “mega” Western NGOs (Catholic Relief Services, MSF, Oxfam International, International Save the Children Alliance, and Word VisionInternational) that account together for 38 percent of total annual spending by NGOs.

20 For instance, relatively conservative estimates put at 1,000 to 2,000 the number of humanitarian agencies involved to varying degrees in the response to theJanuary 2010 Haiti earthquake alone. See Inter-Agency Standing Committee, “Response to the Humanitarian Crisis in Haiti Following the 12 January 2010Earthquake,” Geneva, July 2010, p. 8.

21 John Borton, “Future of the Humanitarian System: Impact of Internal Changes,” Medford, MA: Feinstein International Center, 2009, p. 4.22 See the text box on page 8 of this report.

-

and development. Borton argues that:“It has long been the case that most of the agenciesthat are referred to as ‘humanitarian agencies’ andseen as comprising the ‘Humanitarian System’ alsofunction as ‘development’ agencies.…Conse quently,the drawing of lines around the system necessarilyrequires drawing lines through organisations.”23

The increasing overlap between these two activi-ties, concomitant with the tendency to increasingly

address the underlying causes of crises in additionto their effects, has long been creating tensionswithin the humanitarian system. Indeed, develop-ment actors’ collaboration with governments andlocal authorities to strengthen their capacity to carefor their constituency is often presented as at oddswith humanitarian action, because it may cause aloss of independence and neutrality, especially insituations of conflict.

Jérémie Labbé 7

Figure 2. Map of the humanitarian galaxy

23 Borton, “Future of the Humanitarian System,” p. 6 (original emphasis).

-

Today’s Challenges andTheir Implications

The international humanitarian system hasevolved, somewhat organically, and has continu-ously adapted to the challenges of the time. It grewto maturity in a century characterized by the twoWorld Wars, the Cold War, colonization anddecolonization, the increasing dominance of theWest, the advancement of human rights, theimposition of free-market capitalism as thedominant economic model, and a strong belief inthe capacity of humans to domesticate forces ofnature through scientific and technologicaldevelopments. The humanitarian system is abyproduct of the environment in which it hasevolved. As the world is becoming increasinglyglobalized and interconnected, different globaltrends are shaping the international order andraising a new set of challenges—but also opportuni-

ties—that no one nation can address in isolation. • The world population is growing and becoming

increasingly urban. Recent estimates forecast theworld population reaching ten billion by the endof the century.24 However, this growth is uneven.While most developing nations’ populationsgrow and become disproportionately young—atrend referred to as the “youth bulge”—thepopulation of developed countries tends tostagnate, if not shrink, as it grows increasinglyold. On both sides of the North-South divide,however, the world population has becomemostly urban, with “virtually all of the expectedgrowth in the world population…concentrated inthe urban areas of the less developed regions.”25

• Climate change and environmental degradationincrease stress on the world population. Globalwarming is happening now and is bound tocontinue, worsening preexisting environmentaldegradation—notably deforestation and deserti-

8 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

Coordination and “Centralization” of the Humanitarian SystemOver the last two decades, efforts have been underway to improve the coherence and coordination of the humanitariansystem in response to the constant expansion of the sector and the proliferation of actors. UN General AssemblyResolution 46/182 of 1991 entrusted the world body with this task by creating the position of Emergency ReliefCoordinator (ERC), which bears three main responsibilities: • coordinating the humanitarian assistance of the UN system and liaising with governments and NGOs; • chairing the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), a high-level coordination platform for UN organizations,NGOs, and the Red Cross Movement; and

• administering the Consolidated Appeal Process to coordinate funding appeals. In 1992, the Department of Humanitarian Affairs, which became OCHA in 1998, was established to serve as the

coordination secretariat under the leadership of the ERC.In 2005, the Darfur crisis and the Indian Ocean Tsunami led the ERC to launch a new “humanitarian reform.” This

reform focused on improving coordination by sector through the creation of “clusters,” enhancing the predictabilityand flexibility of humanitarian funding with the creation of pooled funding mechanisms (e.g., the Central EmergencyResponse Fund, or CERF) and strengthening the role of humanitarian coordinators (HCs) at country level.In December 2011, the IASC adopted its “Transformative Agenda 2012,” which focuses on the areas of leadership,

coordination, and accountability. It proposes developing an interagency rapid response mechanism, giving“empowered leadership” to HCs in critical emergencies, reviewing the functioning of clusters to make them leaner andbetter adapted to the context, and enhancing strategic planning and mutual accountability among the differenthumanitarian actors involved in the response.These multiple reforms have undoubtedly improved the coherence of the international humanitarian system but

also increasingly centralized the system under UN leadership. Indeed, despite attempts to entrust actors outside of theUN system with leadership and coordination functions, HCs are overwhelmingly coming from within the UN system;most clusters are headed by UN agencies, and pooled-funding mechanisms are administered by UN entities.

24 Justin Gillis and Celia Dugger, “U.N. Forecasts 10.1 Billion People by Century’s End,” New York Times, May 3, 2011.25 UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision,” New York: 2010, p. 4.

-

fication—linked to human activities like industri-alization and intensive agriculture. Climatechange results in more frequent and intenseextreme-weather events, such as floods, tropicalstorms, and droughts,26 while it aggravates thestress on vital resources like water and food, evenas the population is growing and demandingmore resources.27

• Global inequalities are rising. As global povertyis progressively retreating,28 economic and socialdisparities are becoming more acute, bothbetween countries and within countries. Since1960, the difference in average per capita GDPbetween the twenty richest countries and thetwenty poorest has doubled,29 while studies showthat inequalities have risen within bothdeveloped and developing countries.30 Wholeswaths of the world population and, for thatmatter, virtually entire populations of some of theleast developed nations remain excluded fromeducation, public health, and access to basiccommodities like food and water. The threats thiscreates for social peace and international securityprompted the World Economic Forum to qualifyeconomic disparity as one of the two cross-cutting global risks that “can exacerbate both thelikelihood and impact of other risks.”31

• The world’s economic and geopolitical land -scape is changing. In the last decade, economicinfluence has started to move from Westerncountries to emerging powers. The so-calledBRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China)have grown from one-sixth of the world economyto almost a quarter and are likely to match G7countries’ share of GDP by 2040–2050.32 Thisshift of economic power is accompanied bychanges in the political balance of power.Increasingly, traditional Western powers(including the United States) must cope with the

new assertiveness of the Global South. Thesechanges prompted some analysts to suggest that,instead of a G8 or G20, world affairs will be runby the G-Zero, where no single power or group ofstates will be able to impose its will on the rest ofthe world.33

• The nature of conflicts and violence is changing.Recent studies show that the number of recurringconflicts is increasing.34 Years, if not decades, oflow-intensity but protracted violence place aheavy toll on governance and institutions in statescommonly qualified as “failed” or “fragile.”Globalization has also nurtured new forms ofviolence by international terrorist networks andtransnational criminal organizations, whichfurther complicate the situation in some of these“ungoverned” areas. “The remaining forms ofconflict and violence do not fit neatly either into‘war’ or ‘peace’, or into ‘criminal violence’ or‘political violence’, ” challenging states and sys -tems of global governance to adapt theirapproaches to address new forms of fragility andthreats.35

• The pace of technological development isunprecedented. The development and spread oftechnologies, notably of information andcommunication technologies (ICT), during thelast decade has been phenomenal: the world hasnever been so interconnected, and the diffusionof information has never been so immediate.However, technological developments can alsohave unintended consequences and present theinternational community with new challenges—such as cybercrime and the diversion of technolo-gies to terrorist ends.These underlying global trends have a number of

implications for humanitarian aid and the humani-tarian system, which can be grouped into fourbroad challenges.

Jérémie Labbé 9

26 Although scientists fall short of drawing a clear causal connection between climate change and these types of disasters, their predictions of increased frequency andseverity tend to be confirmed in practice. According to the International Disaster Database (www.emdat.be) of the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology ofDisasters (CRED), University of Louvain, Belgium, the annual average of recorded disasters has already doubled during the last two decades, from approximately200 to 400.

27 Some studies estimate that 350 to 600 million Africans could suffer increased water scarcity if global temperature levels were to rise by only 2 degrees Celsius.Leslie C. Erway Morinière, Richard Taylor, Mohamed Hamza, and Tom Downing, “Climate Change and its Humanitarian Impact,” Medford, MA: FeinsteinInternational Center, 2009, p. 25.

28 “Global Poverty – A Fall to Cheer,” The Economist, March 3, 2012, pp. 81-82.29 Shanza Khan and Adil Najam, “The Future of Globalization and its Humanitarian Impacts,” Medford, MA: Feinstein International Center, 2009, p. 14.30 World Economic Forum, “Global Risks 2011,” sixth edition, Geneva: 2011, p. 10.31 Ibid.32 US National Intelligence Council, “Global Trends 2025: A Transformed World,” Washington, DC: 2008, p. 7.33 Ian Bremmer, Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2012). 34 J. Joseph Hewitt, “Trends in Global Conflict, 1946-2009,” Peace and Conflict 2012 (University of Maryland, 2012), pp. 25-30.35 World Bank, World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development, (Washington, DC: 2011), p. 2.

-

AN INCREASING HUMANITARIANCASELOAD

The converging effects of climate change, popula-tion growth, and rising inequalities point to anincrease in the humanitarian caseload, as morepeople are more vulnerable to a growing number ofdisasters. Oxfam estimated in 2009 that, by 2015,there could be a 50 percent increase in the averagenumber of people affected annually by climate-related disasters compared to the decade1998–2007, bringing the total to 375 million peopleper year.36 It concluded that, given the currentcapacity of the international humanitarian system,the world would be overwhelmed. This estimate remains a crude projection, as the

authors of the study admit. Yet, it reflects a trend—the increased frequency, severity, and scale of bothslow- and rapid-onset disasters due partly toclimate change—that is likely to considerablyincrease the number of vulnerable people in need ofhumanitarian assistance. It is not only the absolutenumber of people who will be directly affected bytomorrow’s disasters that is worrisome; it is alsotheir increasing vulnerability to such shocks, whichare compounded by other underlying factors suchas population growth in poor countries, theconcentration of people in badly planned urbancenters, resource scarcity, and commodity pricevolatility. As the French think tank Groupe URDhas shown in a recent study on “unintentionalrisks,” crises rarely depend on one factor only butusually take place due to the increased “contact”between people and multiple risks, compounded bysocioeconomic and infrastructural vulnerabilities.37For instance, as the Sahel is hit in 2012 by its thirdsevere food and nutrition crisis in less than adecade, the deteriorating resilience of populationsto droughts cannot be explained only by theincreased frequency of this climatic phenomenon—there is also a complex web of interrelated factorssuch as endemic poverty, weak governance,booming population growth, and increasing foodprices.38

Although major natural hazards do not discrimi-nate between the poor and the rich, “poorercommunities suffer a disproportionate share ofdisaster loss.”39 The increased vulnerability tonatural disasters due to poverty was made clear inthe aftermath to the 2010 earthquakes in Chile andHaiti. Although the quake in Chile scored higheron the Richter scale, it killed far fewer: 562 peopledied in Chile, while more than 200,000 died inHaiti. This disproportionate share of loss is particu-larly true of slow-onset processes such as droughts.Wealthier people or countries have resources tobetter cope with such events that can have adisastrous humanitarian impact on people living inextreme poverty or amid protracted conflicts, asillustrated by the 2011 famine in Somalia.THE CHANGING NATURE OF CRISES

Beyond the expected increase of the humanitariancaseload, the nature of the environment in whichcrises occur and the nature of crises themselves arechanging. As the world grows increasingly urban,so does the likelihood that natural hazards orconflicts occur in complex urban environments forwhich humanitarian actors are ill-equipped.40 Thiswas illustrated by the Haiti earthquake in 2010, thefloods that submerged Bangkok in October andNovember 2011, and the conflict in Syria in 2012,where major battles took place in the cities ofHoms, Aleppo, and Damascus.The nature of violence itself is also changing. As

noted above, the boundaries between war andpeace, or between criminal violence and politicalviolence, are increasingly blurred. Some countries,although not formally in conflict, are affected bylevels of criminal violence and human sufferingthat are akin to those of a civil war. In Mexico, thefive-year-old “drug war” launched by the govern-ment against drug cartels has resulted in the deathof more than 47,000 people, according to officialaccounts,41 making it tempting to draw a parallelwith conflicts in Somalia or Afghanistan. If thehumanitarian impact of this type of violence is

10 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

36 Tanja Schuemer-Cross and Ben Heaven Taylor, “The Right to Survive,” p. 25.37 Francois Grünewald, Blanche Renaudin, Camille Raillon, Hugues Maury, Jean Gadrey, and Karine Hettrich, “Mapping of Future Unintentional Risks: Examples of

Risk and Community Vulnerability,” Plaisians, France: Groupe URD, September 2010.38 Peter Gubbels, “Escaping the Hunger Cycle: Pathways to Resilience in the Sahel,” Sahel Working Group, September 2011, available at

www.groundswellinternational.org/wp-content/uploads/Pathways-to-Resilience-in-the-Sahel.pdf .39 UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR), “Risk and Poverty in a Changing Climate: Invest Today for a Safer Tomorrow – Summary and

Recommendations,” Geneva: 2009, p. 4.40 International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, World Disaster Report 2010: Focus on Urban Risk (Geneva, 2010).41 “Mexico Drug War has Claimed 47,500 Victims in Five Years,” The Telegraph, January 12, 2012.

www.groundswellinternational.org/wp-content/uploads/Pathways-to-Resilience-in-the-Sahel.pdf

-

similar to the impact of “traditional” conflicts, withits cortege of displacement, shattered families, andloss of life, it nevertheless forces humanitarianactors to rethink their approach vis-à-vis thedifferent parties. The popular uprisings that haveengulfed North Africa and the Middle East in 2011and 2012—in particular the all-out repression andensuing conflicts in Libya and Syria—mightbecome an increasingly common form of violencein the years to come, as they found their roots in acomplex blend of rising poverty, constrained accessto vital resources (such as food), socioeconomicinequality, and political oppression. While this typeof violence is not new—revolutions and popularuprisings are a recurrent feature of history books—they represent an additional challenge for humani-tarian actors on whom lay unprecedented expecta-tions to be present and do something.These different types of violence and the

recurrence of conflicts in “fragile” or “failed” stateshave led the international community to newapproaches, such as the “stabilization” approachthat now largely informs efforts to address thesecrises. Although there is no commonly agreeddefinition, “stabilization” can be described as apolitical approach that “encompasses a combina-tion of military, humanitarian, political andeconomic instruments to render ‘stability’ to areasaffected by armed conflict and complex emergen-cies.”42 These different instruments are broughttogether in the service of a higher political goal: tosupport the legitimate government in a givencountry in establishing a lasting peace byaddressing the causes of the conflict throughsecurity, good governance, rule of law, sustainableeconomy, and the delivery of basic services.43 If suchan overarching objective is highly desirable, therisks of “politicization” and “militarization” ofhumanitarian aid are hotly debated. Within theUnited Nations—which has used the term stabiliza-tion in the titles of two UN peace operations (in theDemocratic Republic of the Congo and Haiti) andinstitutionalized an “integrated” approach to

peacekeeping and peacebuilding that is akin tostabilization—this approach raises particulardifficulties for humanitarian agencies that areexpected to comply with the broader politicalobjectives of the organization.44

THE RENEWED ASSERTIVENESS OFHOST STATES

Humanitarian actors have always had to deal withissues relating to the national sovereignty of hoststates, particularly in conflict situations where theinternal threats posed by insurgent groups oftencreate hostility toward what is perceived as externalinterference. As a matter of fact, UN GeneralAssembly Resolution 46/182 recognized thecentrality of host states when it stated that “thesovereignty, territorial integrity and national unityof States must be fully respected,” and “humani-tarian assistance should be provided with theconsent of the affected country and in principle onthe basis of an appeal by the affected country.”45 Yet,what the respect of sovereignty actually means inpractice—especially in terms of host states’ controlof international actors’ actions within theirterritory—has evolved over time. Or, as Barnettand Weiss have put it, “the meaning of sovereigntyhas varied from one historical era to another, andthese variations matter greatly for what humani-tarian actors can and therefore should do.”46

The development of human rights and humani-tarian law during the twentieth century hasprogressively transformed the Westphalianunderstanding of absolute sovereignty by imposingobligations on states toward individuals under theirjurisdiction, culminating with the creation of theInternational Criminal Court and the coining of the“responsibility to protect” concept. This normativetransformation coincided with the increasingreluctance of the main donor governments to funddevelopment and humanitarian activities throughdirect bilateral funding to affected states. “Aninternational model of humanitarian assistancetook shape in which it was implicitly assumed thatgovernments were either too weak or too corrupt to

Jérémie Labbé 11

42 Sarah Collinson, Samir Elhawary, and Robert Muggah, “States of Fragility: Stabilisation and its Implications for Humanitarian Action,” Disasters 34, Supplement 3(October 2010): 275-296, p. 276.

43 United States Institute of Peace, Guiding Principles for Stabilization and Reconstruction (Washington, DC, 2009).44 Victoria Metcalfe, Alison Giffen, and Samir Elhawary, “UN Integration and Humanitarian Space: An Independent Study Commissioned by the UN Integration

Steering Group,” London: Overseas Development Institute, December 2011.45 UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182 (December 19, 1991), UN Doc. A/RES/46/182, para. 3.46 Michael Barnett and Thomas G. Weiss, Humanitarianism Contested: Where Angels Fear to Tread (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 23.

-

manage large volumes of humanitarian aid.”47 Thisnew funding model increasingly circumvented hostgovernments when it came to the use of aid and itsdelivery to the population, arguably decreasing thecapacity of government institutions to care for theircitizens.While the alteration of absolute state sovereignty

continues today, current geopolitical changes are, inparallel, giving more leeway to host countries tomore assertively call for respect of their sovereignty.Traditional powers that used to set the agenda—and the norms regulating international affairs—areprogressively ceding ground to emerging powerswary of breaches of their sovereignty such as Brazil,China, India, and Turkey. Human rights andhumanitarian ideals have entered the mainstreamof the international community’s values, and theidea that states have responsibilities toward theirown population is broadly accepted. Yet, paradoxi-cally, recent years have also seen a reassertion of thesovereignty argument in a number of violentcontexts, such as those in Sri Lanka, Sudan, andPakistan, where national governments play onshifting political power to resist pressure (usuallycoming from major donors) to open up to humani-tarian aid.The renewed assertiveness of host states is

reflected—and reinforced—by recent trends in thedevelopment aid sector, which saw the adoption ofthe 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness.This declaration puts the recipient governmentback at the center of development aid, emphasizingnational ownership of development strategies andalignment of donors. These policy developmentshave not yet been fully reflected in humanitarianpolicy and practice, where “the state-avoidingmodel of international assistance largely remains inplace.”48 Yet, as Randolph Kent, director of theHumanitarian Futures Programme at King’sCollege, stated: “Governments in some of the mostvulnerable regions of the world are becomingincreasingly reluctant to have traditional humani-tarian actors behave as they’ve done in the past.”49

As developing countries have more resources tocare for their populations and develop bettergovernance structures, they are determined toensure greater coordination and control over theaid that flows in. This change is illustrated by thecurrent mushrooming of “humanitarian affairs”and “emergency relief ” departments withinnational governments and regional intergovern-mental organizations such as the League of ArabStates (LAS), the Organisation of IslamicCooperation (OIC), the Economic Community ofWest African States (ECOWAS), and theAssociation of South-East Asian Nations(ASEAN).50

These transformations present opportunities, asimproved involvement of emerging powers in thedesign and functioning of the system will increaseits legitimacy and help reduce the perception ofWestern-dominance. On the other hand, in conflictsituations, current global economic and geopolit-ical changes give more leeway to host governments,who may be implicated in the conflict, toundermine the delivery of principled humanitarianaid.THE FINANCING OF HUMANITARIANACTION

The year 2010 saw the largest annual humanitarianresponse on record, with an estimated $16.7 billionfrom governmental and individual donors.51 Inother words, the formal international humanitariansystem is better funded than ever before. Yet, thispositive assertion masks other underlying trendsthat raise questions for the future of humanitarianfinancing.First, the humanitarian system needs more

resources because it has to face a likely increase ofthe humanitarian caseload, as discussed previously.Oxfam estimated that, in order to maintain currentlevels of humanitarian response to the projected375 million people mentioned above, the world willhave to spend around $25 billion per yearcompared to the record-high $16.7 billion in 2010.52The system is also demanding more resources

12 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

47 Harvey, “Towards Good Humanitarian Government,” p. 1.48 Ibid.49 Randolph Kent, “Humanitarian Sector Needs a Radical Rethink,” AlertNet, January 25, 2012, available at

www.trust.org/alertnet/blogs/alertnet-aidwatch/humanitarian-sector-needs-a-radical-rethink/ .50 ALNAP, “State of the Humanitarian System, 2012 Edition,” p. 27.51 Development Initiatives, “GHA Report 2011,” p. 6.52 Schuemer-Cross and Taylor, “The Right to Survive,” p. 93.

www.trust.org/alertnet/blogs/alertnet-aidwatch/humanitarian-sector-needs-a-radical-rethink/

-

because it has substantially expanded its activities.Major humanitarian agencies no longer limitthemselves to traditional relief activities like foodassistance, health, nutrition, sanitation, and shelter;they increasingly engage in protection activities,human rights advocacy, disaster risk reduction,peacebuilding programs, and the like. This isfurther compounded by the fact that humanitarianassistance is also more expensive now than before,not least due to the substantial increases in foodand oil prices over the last few years.Second, global humanitarian funding is still

dominated by “traditional” humanitarian donors:mostly developed Western member states of theOECD-DAC, which provided $11.8 billion of theestimated $12.4 billion of global governmentalsources in 2010. However, this financial dominancemight change due to several factors. The progres-sive shift of economic power described above mightwell undermine the sustainability of this source offunding, which has been aggravated by budget cutsand austerity measures to cope with the effects ofthe global economic crisis. The ability of traditionaldonors to contribute to humanitarian assistance inthe long run might be further constrained bydemographic trends. The smaller size of theworking-age population in traditional donorcountries is likely to reduce the tax base and putstrains on national budgets, while aging popula-tions mean that precious resources for foreign aidare likely to be diverted to domestic health andgeriatric care.53 These projections tend to beconfirmed if one looks more closely at the 2010record-high humanitarian response, which actuallymasked reduced expenditure levels of eight OECD-DAC members for the third consecutive year.54

The shift in economic power means that formerlylower-income countries now have the financialcapacity—and growing political will—to extend ahelping hand to populations abroad that areaffected by crises. Indeed, the last decade saw theemergence of new donor governments, who are notmembers of the OECD-DAC, that increasinglycontribute to foreign aid, such as Brazil, China,

India, Turkey, and the Gulf states. Given theirgrowing economic weight, this trend is set tocontinue. Yet, several studies showed that non-DACdonors still tend to favor bilateral channels that falloutside of international donor coordinationmechanisms. Their support therefore does notbenefit the formal humanitarian system and createsrisks of duplication of efforts and gaps in service.55Although emerging powers’ contributions topooled funding mechanisms and internationalagencies have increased in recent years, thechallenge for the humanitarian system remains toconvince them that fully joining the existingcoordination and funding mechanisms is in theirinterest.

A Six-Point Agenda forAdaptation

Actors in the international humanitarian system arewell aware of these challenges. In recent years, anumber of research projects and studies emanatingfrom within the system have strived to identify thechallenges ahead and the measures needed tosuccessfully meet them.56 Although diverging viewsexist in the formal humanitarian system, somecommon denominators can be identified. Inmainstream humanitarian thinking, the recipe foradaptation consists of six active ingredients:1) Anticipate the risks2) Strengthen local capacities and resilience3) Develop new partnerships4) Enlarge the funding base and use it moreeffectively

5) Enhance coordination, leadership, accounta-bility, and professionalization

6) Make innovations and leverage new technolo-gies

1. ANTICIPATE THE RISKS

Given the changing nature of crises and a growinghumanitarian caseload, the best way to tackle theeffects of disasters and crises with finite resources

Jérémie Labbé 13

53 Carl Haub, “Demographic Trends and their Humanitarian Impacts,” Medford, MA: Feinstein International Center, November 2009, p. 8.54 Development Initiatives, “GHA Report 2011,” p. 6.55 Andrea Binder, Claudia Meier, and Julia Steets, “Humanitarian Assistance: Truly Universal? A Mapping Study of Non-Western Donors,” Berlin: Global Public

Policy Institute, August 2010, p. 25; Adele Harmer and Ellen Martin, eds., “Diversity in Donorship: Field Lessons,” London: Overseas Development Institute, March2010, p. 5; Alain Robyns and Véronique de Geoffroy, “Les Bailleurs Emergents de l’Aide Humanitaire: Le Cas des Pays du Golfe,” Plaisians, France: Groupe URD,November 2009, pp. 16-18.

56 See footnote 2 above.

-

might well be to anticipate them by identifyingtheir causes, in order to prevent their worst effects.In other words, “Humanitarian organizations haveto be increasingly aware of the root causes ofvulnerability and, moreover, of the continualinterface between myriad factors on differenttemporal planes influencing both slow-onset andrapid-onset risks.”57 With regard to rapid-onsethazards like floods and earthquakes, recent studiesshow that disaster-related mortality and assetdestruction is concentrated in small areas exposedto infrequent but extreme hazards.58 Exposure ofpopulations to rapid-onset hazards is often exacer-bated by a number of factors, such as unplannedurbanization of flood-prone areas or deforestationof hill slopes amenable to landslides. Even if allhazards cannot be systematically anticipated, theirlikelihood in certain geographic areas and potentialimpact on populations can be fairly well estimatedwith modern knowledge and technologies. This isalso true of slow-onset hazards such as droughtsand protracted conflict or violence. In all likeli-hood, acute humanitarian needs will increasinglyresult from the conjunction of slow-onset processeswith pre-existing poverty, an absence of socialsafety nets, a scarcity of vital resources, and marketdisruption or economic shocks, in addition to thedirect effects of massive, rapid-onset catastrophessuch as earthquakes. Anticipation has two facets. First, further refining

early-warning systems and mainstreaming their usewill allow the authorities, communities, andhumanitarian actors to foresee the occurrence ofdisasters in advance and to be better prepared todeploy a timely response, provided the necessaryfunding is made available. Second, humanitarianactors have to better understand and identify the“myriad factors” influencing vulnerability anddemanding life-saving assistance. As Groupe URDhas stressed, “the evaluation of vulnerabilities is thefirst and perhaps most important step towards thedevelopment of societies which are more resilient tofuture unintentional risks.”59 While this is theprimary responsibility of states, it also requires afundamental shift in the way humanitarian actorswork by incorporating analysis and monitoring

capacities of vulnerabilities and their causes intotheir strategic and operational decision-makingprocesses. A better understanding of the causes ofvulnerability will allow for the development ofindicators and triggers for action, and facilitate amove from a shock-driven approach—that is, inreaction to a highly visible shock—to a genuinelyneeds-driven one.2. STRENGTHEN LOCAL CAPACITIESAND RESILIENCE

The same reasons that underpin the need to betteranticipate risks led most humanitarian actors toembrace the Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR)agenda—which took preeminence with theadoption of the Hyogo Framework for Action in2005—and to strive to better link relief, rehabilita-tion, and development activities, a processcommonly referred to as LRRD. These twoconcepts indicate that the best way to addressfuture humanitarian needs is to enable both theauthorities and the population to prepare fordisasters and to cope with their effects. Thisrequires enhancing the capacities of national andlocal authorities to take care of their population andstrengthening the resilience of affected communi-ties. States have the responsibility “first and foremost

to take care of the victims of natural disasters andother emergencies occurring on [their] territory.”60Humanitarian actors have to overcome their state-avoiding reflexes and work with governments tobuild relevant institutions and mechanisms toreduce risks and deliver an appropriate humani-tarian response to their population. Such a shifttoward a more collaborative approach is all themore necessary as host states are increasinglyresistant to what they perceive as external interfer-ences. While capacity-building efforts should bestraightforward when states are willing to care fortheir population, this will be more challengingwhen this will is absent or is limited to a segment ofthe population. Humanitarian actors will thereforeneed to carefully look at a state’s capacities anddesire to respond before determining their role.They will need to adapt their approach from full-

14 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

57 FIC/HFP, “Humanitarian Horizons,” p. 26.58 UNISDR, “Risk and Poverty in a Changing Climate,” p. 3.59 Grünewald et al., “Mapping of Future Unintentional Risks,” p. 49.60 UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182, para. 4.

-

fledged alignment with governmental strategiesand support of the state’s institutions to advocacyand support of civil society, depending on thecircumstances.61

Regardless of the will and capacities of states tocare for their populations, humanitarian actors alsoneed to better engage local communities bylistening to their concerns and encouraging theirparticipation in humanitarian programming. Bydoing so, humanitarian actors can help build, in aconcerted manner, local communities’ capacity towithstand and react to crises. Relief agencies mustwork better with their development counterparts tostrengthen the resilience of local populations toshocks in the longer term and avoid costly relapsesinto crises. Building the population’s resilience alsoimplies empowering civil society organizations,which are usually the first responders to a disaster.Although international humanitarian agencies areaware of the shortcomings and improvements havebeen made in recent years, the modern interna-tional humanitarian system still tends to sidelinethese important actors, not least in coordinationfora, favoring a top-down approach that sometimesundermines local capacities altogether.62

3. DEVELOP NEW PARTNERSHIPS

The increasing humanitarian caseload andchanging nature of crises raise fears that thehumanitarian system, constrained as it is by finiteresources, will not be able to face these growingneeds. Better anticipating threats and operating innew environments, such as urban areas, requiresskills, means, and knowledge that are not readilyavailable within the system. Humanitarian actorsmust learn how to better work with experts indifferent fields, such as meteorologists, economists,or demographers, if they want to adapt successfullyto tomorrow’s crises.Meanwhile, the humanitarian system has already

opened up, more or less willingly, to a number of“nontraditional” actors playing an increasing role inemergency relief or in the environment wherehumanitarians operate. New partnerships must bedeveloped with these “nontraditional” actors:national militaries, private military and securitycompanies, corporations, religious institutions, and

diaspora communities. Partnerships will allowadditional human and technical expertise to bemobilized and expand the coverage of humani-tarian response. In the same vein, developingpartnerships is a condition for strengthening theresilience of affected populations, as it is key toempowering and enhancing the capacities ofcommunity-based organizations to prevent andrespond to crises. While increased involvement of other actors in

humanitarian efforts is badly needed, it is alsofraught with risks. Military forces or corporationsmight have unique means or specific skills tocontribute to relief operations, but they have alimited understanding of the specific environmentof crises and of humanitarian practices andstandards developed and tested over decades offield activities. Arguably, active engagement withnew partners will allow for maximizing theresponse while avoiding the undermining ofexisting humanitarian principles, standards, andprocesses. 4. ENLARGE THE FUNDING BASE ANDUSE IT MORE EFFECTIVELY

The funding conundrum—namely, doing morewith finite resources—can be resolved by followingtwo parallel and complementary tracks: moreefficiently disbursing existing funding and lookingfor nontraditional sources in addition to traditionalones. The former track requires efforts from both

operational humanitarian actors that disburse themoney and traditional donors. There are ways tomake the money more readily available, distributedtransparently, and in accordance with assessedneeds through further development and improve-ment of pooled funding mechanisms such as theCentral Emergency Response Fund (CERF)administered by OCHA. Although widelyacclaimed since its restructuring in 2005 as part ofthe broader reform of the humanitarian system,CERF still suffers from a number of shortcom-ings—for example, its inability to directly fundNGO projects creates an additional bureaucraticlayer and delays in disbursing funds. Inconsequence, NGOs also advocate to maintain

61 Edmund Cairns, “Crises in a New World Order,” p. 19.62 ALNAP, “The State of the Humanitarian System: Assessing Performance and Progress,” London: Overseas Development Institute, January 2010, pp. 37-39.

Jérémie Labbé 15

-

channels of funding other than UN-administeredpooled mechanisms, such as the recent Consortiumof British Humanitarian Agencies (CBHA), anNGO consortium that makes pooled funds readilyavailable to its members in case of emergency.63Improvements do not necessarily require moregenerosity from traditional donors, but increasedpolitical will to fully comply with the GoodHumanitarian Donorship (GHD) principles towhich they signed up.64 For instance, a reduction inearmarking would allow better allocation of fundson the basis of need only and contribute to morepredictable, flexible, and timely funding, in linewith the GHD principles.But a more efficient use of existing funds might

not be enough to face increased needs. As shownearlier, the amounts contributed to the formalinternational humanitarian system remainmarginal compared to the overall contributions todisaster relief made through remittances, directforeign assistance, and domestic revenues ofaffected states. The GHA Report acknowledges thatglobal humanitarian assistance far exceeds the$16.7 billion reported for 2010. By way of example,it mentions the $6.2 billion spent over the last fiveyears by the Indian government in its own countrythat dwarfs the $315 million received fromdonors.65 India and other emerging powers areincreasingly capable and willing to deliver aid, notonly to their own population but also to affectedpopulations abroad. Humanitarian actors are wellaware of this and must develop outreach toemerging donors, an effort that is largely underway.5. ENHANCE COORDINATION,LEADERSHIP, ACCOUNTABILITY, ANDPROFESSIONALIZATION

Given the expansion of the humanitarian systemand its increasing diversity, coordination andleadership are crucial to facing tomorrow’schallenges efficiently. In the last two decades, therewere considerable efforts to bring more coherenceand better coordination within the humanitariansystem under the leadership of the UN.66 Although

successive reforms have brought some noticeableimprovements to the humanitarian system overall,there are widely shared views that some shortcom-ings and weaknesses still need to be corrected. More competent and experienced leadership

within the UN is central to this task, due to thedominant coordinating role of the world body. Thisapplies both at the management level—notably, forthe complex position of humanitarian coordinator(HC) that is often combined with the more politicalfunction of resident coordinator (RC)—and at thetechnical level, within the global and country-levelclusters. At the management level, a number ofrecent evaluations revealed rather poor perform-ances of HCs, not least because they come, moreoften than not, from the position of RC andtherefore have no, or limited, previous humani-tarian experience.67 However, the need forenhanced leadership does not concern only the UNbut also the NGO sector, which, in absolutenumbers, employs more than half the staff in thehumanitarian system and delivers the majority ofaid.68 The functioning of “clusters” also needs to beimproved to make them less bureaucratic andprocess-driven, more inclusive of national and localactors, and more participatory. As humanitarian needs increase, so does the

pressure on humanitarian organizations to beaccountable to the populations they help, as well asto donor governments and individuals.Accountability to affected populations is key toensuring that aid is adapted to their needs andcontributes to strengthening their resilience. Itrequires mainstreaming participatory approachesin both the programming and implementation offield activities, so that affected local communitiescan contribute to designing programs sensitive totheir needs, but also channel their complaints incase their needs are not being met properly. At theother end of the spectrum, humanitarians areexpected to be accountable to donor states andtaxpayers and justify that increasingly scarceresources are used to the best effect.

63 Sean Lowrie and Marieke Hounjet, “The Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies: A New Initiative of NGO Collaboration,” Humanitarian Exchange, No. 50(April 2011): 26-28.

64 The GHD initiative, which now gathers thirty-seven donor governments, has developed a set of twenty-three principles adopted in 2003 that aim to make humani-tarian aid more principled, predictable, and effective. For more information, see www.goodhumanitariandonorship.org .

65 Development Initiatives, “GHA Report 2011,” p. 6.66 See the text box on page 8 of this report.67 Ashdown, “Humanitarian Emergency Response Review,” pp. 19-21; Dempsey and Kyazze, “At a Crossroads,” p. 20.68 Dempsey and Kyazze, “At a Crossroads,” p. 21.

16 RETHINKING HUMANITARIANISM

www.goodhumanitariandonorship.org

-

The Transformative Agenda recently adopted bythe UN’s Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC)is an attempt to improve the performance of thehumanitarian system in the key areas of leadership,coordination, and accountability.69 But beyond suchefforts, there is a growing thrust toward profession-alization of the humanitarian system as a whole—professionalization of individuals working in thesystem but also of the organizations themselves.Over the last few decades, a number of qualitystandards and guidelines were adopted to profes-sionalize the sector, such as the Sphere Project, theQuality COMPAS, and the HumanitarianAccountability Partnership.70 Yet, some envisagethat, just as lawyers, doctors, or architects havebrought consistency to their profession by creatingprofessional bodies, the humanitarian systemshould work toward establishing certification andaccreditation mechanisms and, eventually, its owninternational professional association.71

6. MAKE INNOVATIONS ANDLEVERAGE NEW TECHNOLOGIES

The ability of humanitarian actors to face thechallenge presented by an increasing caseload andthe changing nature of crises will also depend ontheir capacity to innovate and better harness newtechnologies, in particular ICTs. The developmentand spread of ICTs, in particular mobile phonetechnologies, opens new opportunities to quicklyraise funds directly from the population ofwealthier nations,72 to interact with and engagecommunities living in the most remote andinsecure areas,73 and to deliver assistance or protec-tion in ways not thought about before.74 Similarly,the continued improvement of weather-forecastingtechnologies, climate science, and satellite imagerywill contribute to improving early-warningsystems, so that actors can better anticipate and

prepare for future hazards.However, using technological developments to

the best effect requires investment in research anddevelopment and taking risks in innovation, towhich humanitarian actors and donors are usuallyaverse. “Traditional donors remain very project-based in their grant making and humanitarianorganizations project-based in their culture,preventing the large-scale, necessary changes inhow aid is conceived and delivered for tomorrow’sworld.”75

Underlying this six-point agenda, there is broadagreement that if it is to appropriately adapt totomorrow’s challenges, the humanitarian sectormust do so while safeguarding its deontologicalfoundations. In order to save lives, reduce suffering,and preserve human dignity, humanitarian actorsmust act within an ethical framework that makesthis task possible. They should be motivated by thesole aim of helping other humans—as opposed to,for instance, making profit—and should do sobased on an objective assessment of needs andwithout any further discriminations. Independenceand neutrality of organizations is believed to enablerespect for the principles of humanity andimpartiality, particularly in conflict situations.76

Yet, humanitarian principles are challenged onseveral fronts, and by some of the very changesrequired within the system itself, as describedabove. The rapprochement of development, humanrights, and humanitarian agendas deemednecessary to address causes of crises, mitigate theireffects, and hence better cope with a growinghumanitarian caseload questions the ability ofhumanitarian actors to remain neutral andindependent. Indeed, working with national

69 “IASC Transformative Agenda 2012,” adopted by the IASC Principals in December 2011, available at www.humanitarianinfo.org/iasc/pageloader.aspx?page=content-template-default&bd=87 .