Restorying the Wild Wren Smith - National Association … naturalist Robert Bridges heads up a group...

Transcript of Restorying the Wild Wren Smith - National Association … naturalist Robert Bridges heads up a group...

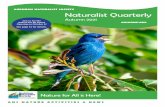

"Restorying" the Wild, by Wren Smith ______________________________________________________________ As a child, whenever I had a few hours to explore the woods, I'd make myself a nest out of soft pine needles or leaves and downed branches. I'd settle back and enjoy this tiny world feeling a sense of connection and very rested. In fact, for years afterwards I misspelled forest, believing it contained two "r"s—"for rest." It wasn't that I used my little "nest" for any real slumbering, but I entered a sort of meditative reverie. Like Saint-Exupery's Little Prince, my world was not much bigger than myself and yet it contained all the magic and potential of the universe. Sunshine and shadows danced at my fingertips. A limb moved here and a window opened there. In this tiny patch of wildness with its parade of insects disguised as sticks and thorns, its pungent earthy smells, I sensed that I too was one of nature's creatures, part of a much larger story. Bernheim Forest is a 14,000-acre nature oasis just 30 minutes south of Louisville, Kentucky. Coming to this country as a teenager in 1867 with four dollars in his pocket, Isaac W. Bernheim ultimately made his fortune in the whiskey industry. Sensing that some day, young people would grow up in a world of concrete and steel removed from the healing influence of nature, Mr. Bernheim eventually purchased most of the land that has become such a source of renewal for so many. Although Mr. Bernheim may never have used the word restoration, it is clear from many of his actions that he understood the concept. In fact, when Mr. Bernheim purchased the land it was not the beautiful, holy, or whole place it is today. The land had been severely damaged by practices that left the forest almost bereft of trees—first by extensive farming and later by the salt and iron ore industries. Mr. Bernheim understood that with time, good planning, and hard work the land would be restored to a place of grace and beauty. It is evident that he also believed that people would respond not only on a physical level but also on a spiritual one. As part of the formal opening announcement for Bernheim in 1930 he said, "To all I send the invitation to come from city, village, hamlet, and farm to re-create their lives in the enjoyment of nature and the many blessings she gives with open hand to those with understanding." Today, Bernheim's legacy is evident in the lives of the people who are touched by this special place. Robin Mayberry, a petite woman in her twenties, sits on a bench near Bernheim's Sun and Shade trail. It has been a stressful week—too much to do, not enough time to do it—but she is letting go of all that now. She just finished a hike along a hilly section of the trail and her body is responding by releasing endorphins. Robin begins to breathe slowly and deeply as she marvels at the luminous light from the forest canopy and the interplay of shadows. She listens to the flute-like songs of the wood thrush and the gentle flow of a nearby stream. Later, on her 30-minute drive back home to Louisville, Robin realizes that she is not the same stressed and angry person that she was just three hours ago as she headed out to Bernheim. She notes that her foot is lighter on the gas pedal and she doesn't feel the tide of anger rise when another driver cuts dangerously close. Her shoulders aren't hunched up around her neck but hang loose and relaxed. She is feeling calm and centered as if she just had a massage. Robin shared this story during a training session at Bernheim, but she went on in her clear, soft voice to tell us more. "So often our lives run at such a fast pace, with kids, responsibilities, etc., it's easy to get caught up in that…but when I immerse myself in places like Bernheim, it's as if I take on the pace and the flow of the natural world…. Besides, the air is cleaner and being out getting exercise is good too." Ecologist and writer Gary Paul Naban suggests that to preserve and protect the places that we love we must find ways to "re-story" them—to make these places a part of our own life stories, festivals, and celebrations. Implicit in this idea of "re-storying" is an understanding that the work of restoration often happens on many levels: physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. Allen Peacock, another naturalist trainee, shares support for this holistic view of the restorative process. Allen, a gifted artist, whose mannerisms suggest a gentle heart and penetrating mind, tells us that spending time close to nature improves his overall state of being. Allen then makes a lovely case for the language of the senses when he says, "It's as if by osmosis—through my eyes, my ears, my nose, and by touch—these wonders (of nature) minister to my heart giving me health and wholeness and peace." It's not just the environment that is damaged when we destroy beauty but also the more tender and beautiful offerings from other peoples' hearts. Destructive actions keep us cut off from creation and intimacy with others, and true knowledge and love of ourselves. Whenever we create beauty, plant a garden, or restore a forest or a stream we nurture our own souls." Volunteer naturalist Robert Bridges heads up a group of Trail Scouts that often spend days in the woods clearing trails of fallen trees and repairing foot bridges and such. He says, "Doing physical work in the woods is a great

way to burn off some energy." He says that most of the folks who help him with those projects say that it's also a way to give something back. Portia Brown talks about the spiritual lift she gets volunteering as a naturalist leader. She says of her work here, "It really brings home the sometimes elusive concept that we are each part of a much larger community. Bernheim, the physical place, provides large habitats, making a significant contribution to the well-being of communities of native flora and fauna; this is exciting in and of itself. The research, public educational programs, designed landscapes, and tree collections benefit human communities in many ways. No matter what may be going on in one's personal life, one never leaves Bernheim without being touched by this contagiously uplifting sprit." Naturalist trainee Terell Holder says, "Some people come simply to lay back on blankets in a beautiful place, dozing and just being quiet. The more you connect with the natural world, even in the simplest of ways, the more likely that connection will stay with you. The peacefulness of the "woods" can be conjured in a moment in the yard, the landscaping around the office, or in the changing of the clouds in a brief glance out the window." But some visit Bernheim for more specific reasons. These are the folks that seem to carry some of the earth, both literarily and figuratively deep within their bones. They seek out places like Bernheim because of a sense of resonance. This resonance acts like an interior sounding board from which their personal authority arises. It's as if they need to listen to the myriad voices of insects, trees, and toads in order to feel right with the world. Knowing the importance of this in my own life, I've pondered how and to what extent this resonance, which can also be described as "rootedness" works towards restoring health, wholeness and holiness in our lives. What are the experiences that allow us to hear stories on such a level that they become not only deeply entwined with our own but restorative as well? The German-speaking poet Rainer Maria Rilke has left us with a powerful image by proclaiming in The Book of Hours, "If we listened to earth's intelligence we could rise up rooted like trees." Kayla is perched on her haunches near Rock Run. An eight-year-old with dark eyes and deep caramel complexion, Kayla motions to her friends and calls out excitedly, "Look, I found one—a caddisfly larva. Come see, come see!" The volunteer who has taken this group of young girls to explore life in the creek peers over Kayla's shoulder into the shallow water and nods appreciatively. She encourages Kayla to notice the tiny sticks used by the larva to craft its home. Later the girls write and draw in their journals. Kayla shares hers with the group. It's a colorful caddisfly larva and beneath it Kayla has written, "The caddisfly makes its home from nature, nature is my home too!" Perhaps such an observation made during these formative years will lay the foundation for a relationship with the natural world that can enrich Kayla's life and give her body and spirits a lift when they need restoring. As philanthropist and social worker Edith Cobb suggested in her ground-breaking research, The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood, published in 1959, there is a period of middle childhood when children are especially open to developing a deep bond with nature. Those who find spiritual as well as physical nourishment from the natural world often share stories of times wandering and exploring woods, creeks, and canyons of their childhood. These early experiences provide the foundation for reading nature's language—for being able to pick out the patterns that form the stories of plants, animals, landscapes, and people. When we sense these stories expressed in the songs of birds, the mystery of light inside a canopy of leaves and the deep, relaxed breathing of our own bodies, we often experience wholeness (holiness), wellness, and restoration. A common thread in many early nature experiences is that of building dens or forts in a nearby field or weed lot, under the sweeping boughs of hemlock or pine trees, or perhaps deep in the tangle of vines. In partnering with these elemental forms, children nurture an early sense of connection with nature as they create a safe place to take in the sights, sounds and the fragrances of the season. Perhaps someday, Kayla will take her granddaughter to play along a stream at Bernheim. Perhaps they will wander along the tree-lined banks and find a good-sized sycamore tree sprawling along the bank near a curve in the stream. Perhaps they will climb barefooted upon the anaconda-like roots where a deeper pool of water is now home for numerous minnows, tadpoles, and whirly gig beetles. Perhaps Kayla will peer over her granddaughter's shoulder into the clear waters of Wilson Creek and they will both be renewed by what they find there.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About the Author As a child Wren and her family made several visits to Bernheim Forest, which she credits for helping her discover her calling as a naturalist. Today Wren is the interpretive programs manager for Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest. Wren has begun Bernheim's Training-for-Naturalists program to help Bernheim meet its mission of connecting people to nature. Wren can be reached at [email protected].

Copyright © 2008 National Association for Interpretation. Legacy July/Aug 2005