RESEARCH REPORT FRAGILE BUT NOT HELPLESS Scaling Up ... But Not Helpless UK... · FRAGILE BUT NOT...

Transcript of RESEARCH REPORT FRAGILE BUT NOT HELPLESS Scaling Up ... But Not Helpless UK... · FRAGILE BUT NOT...

RESEARCH REPORT

FRAGILE BUT NOT HELPLESSScaling Up Nutrition in Fragile and Conflict-Affected StatesDR SEBASTIAN TAYLOR

April 2013World Vision UK-RR-CH-02

AcknowledgementsThis research was undertaken and report written by Dr. Sebastian Taylor, an independent consultant. Thanks are due to Andrew Griffiths, Emily Cooper, Besinati Mpepo of World Vision UK and Kate Eardley and Lisa O’Shea of WV International; Dr Rob Hughes (UK Department for International Development), Leni Wild (Overseas Development Institute), Laurence Chandy (Brookings Institute) and Rob Page (International Development Committee) for their work on the External Reference Group; Dr Eric Brunner and Dr Carolina Perez-Ferrer (Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London) for their brilliantly insightful help with the quantitative analysis; Dr David Nabarro, Pau Blanquer and Martin Gallagher (SUN Secretariat Coordinator and team, Geneva) for their generous engagement. Thanks to the Internal Reference Group across the World Vision Partnership: Colleen Emary, Geraldine Ryerson-Cruz, Susie Grady, Marwin Meier, Mami Takahashi, Sharon Marshall, Sheri Arnott, Andrew Hassett and Chris Derksen-Hiebert. Thanks also to Jeremiah Sawyerr (WV Sierra Leone), Guy Bokongo (WV DRC) and Dr Ahmad Shakib (WV Afghanistan) for their unswerving efficiency in setting up field visits, and to the staff of government ministries, UN agencies, international and domestic NGOs, donors and project and programme beneficiaries in Sierra Leone, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Yemen, and Pakistan for their time and openness.

Thanks to UKAid and World Vision UK as well as World Vision International and the Child Health Now Campaign for funding the project, and to the Government of Ireland, the Minister for Overseas Development and Trade, and Irish Aid for launching it.

Disclaimer: While the author is grateful to all who have contributed to this work in one way or another, the views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily representative of the funders, World Vision and DFID, nor any of the contributors.

Cover image: Living in Afghanistan, Fattema is 30 years old and her husband is a farmer who bings in about a dollar a day by working on other people’s land as a labourer. They have had 6 children but 2 of them have died. She is joined here by here 2 year old daughter and 3 year old son. Fattema says, “I did not breast feed properly, I used a formula of some kind. I have learned that babies need other food.” She says, “My dream is to have my children healthy, and to have shoes.”© 2012 Paul Bettings/World Vision

Opposite: Children at a school in Herat, Afghanistan, whose lessons now include hygiene education. © 2012 Paul Bettings/World Vision

Published by World Vision UKOur child safeguarding policy prevents us from showing the faces of any girls affected by early marriage. All images used were taken with permission from similar contexts and are not linked to the specific stories in this report. All quotes from research respondents displayed in this report were given anonymously and are attributable by gender, age and location only.

© 2013 World Vision UKAll photographs: © World Vision

World Vision UKWorld Vision House, Opal Drive, Fox Milne, Milton Keynes, MK15 0ZRwww.worldvision.org.uk

World Vision UK – London office11 Belgrave Road, London, SW1V 1RB

World Vision is a registered charity no. 285908, a company limited by guaranteeand registered in England no. 1675552. Registered office as above.

“There is little doubt that SUN can work in fragile and conflict-affected states”

Government, DR Congo

Contents

Acronyms and Abbreviations 4

Background 5

Executive Summary 6

Key Findings 9

Concluding Observations and Recommendations 24

References 25

Annex 1 30

Acronyms & AbbreviationsAfDB African Development BankCAADP Comprehensive African Agricultural Development ProgrammeCPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (World Bank)CRS Creditor Reporting System (OECD-DAC)D/GBS Direct/General Budget SupportDFID Department for International Development (UK)DRC Democratic Republic of CongoFAO Food and Agriculture OrganisationFCAS1 Fragile and conflict-affected stateG7/8 Group of Seven/Eight (major donor countries)G7+ Group of fragile and conflict-affected states (see OECD International Dialogue on Peace building and Statebuilding)GDP Gross Domestic ProductGHA Global Humanitarian Assistance report (Development Initiatives)GNI Gross National IncomeIDS Institute for Development Studies (University of Sussex)IFI International Finance InstitutionsIFPRI International Food Policy Research InstituteIYCF Infant and Young Child FeedingKP/FATA Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (formerly NWFP)/Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Pakistan)LNS Lancet Nutrition Series (2008)MDG Millennium Development GoalNEPAD New Partnership for Africa’s DevelopmentNGO Non-government organisationODA Official Development AssistanceODI Overseas Development InstituteOECD-DAC Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development – Development Assistance CommitteeOOP Out of pocket (expenditure)REACH Renewed Efforts Against Child Hunger SUN Scaling Up NutritionUK United KingdomUN United NationsUNDP United Nations Development ProgramUnicef United Nations Children’s FundUS United StatesUSAID United States Agency for International DevelopmentWFP World Food ProgrammeWGI Worldwide Governance IndicatorsWHO World Health OrganisationWV World Vision

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

4

1 Countries are defined as FCAS by various institutions, including the World Bank, the OECD, and DFID. FCAS implies both overt crisis (organised conflict and violent disruption of socio-political processes), and latent fragmentation (contested political settlement, state predation, and failure to ensure basic rights and services). Net effects include potential loss of regime legitimacy, control of the use of force and provision of security, and inability or unwillingness to provide for basic livelihood conditions. Most FCAS manifest some combination of these problems.

Background‘Malnutrition’2 is an underlying cause of a third of child deaths globally.3 Acute malnutrition (wasting) directly contributes to child mortality through increased vulnerability to primarily infectious diseases. Chronic malnutrition (stunting) increases mortality, but impacts more widely through irreversible, lifelong physical and cognitive impairment. Chronic malnutrition undermines a country’s productive population and its chances for economic growth, as well as storing up potentially catastrophic costs in health care.4 In the 36 high-burden countries in the Lancet Nutrition Series (LNS, 2008), malnutrition costs an estimated USD$260bn per year.5 By contrast, a dollar investment in nutrition intervention can yield up to USD$30 in return.6

The prevalence of child malnutrition is comparatively high in fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS).7 Disruption of food production and supply, destruction of household assets and livelihoods, mass displacement of population, and degradation of vital services including health are all associated with rapidly escalating levels of acute malnutrition.8 But the causal relationship is two-way. It is increasingly recognised that food and nutrition insecurity are associated with heightened risk of violent social unrest and conflict.9 Despite this, the international community has neglected investment in nutrition in FCAS, a trend this report aims to address.

After several decades of progress, global reduction in malnutrition has stalled – partly undermined by the recent interlinked global food, fuel and economic crises from 2007-08, but partly also by stagnant or worsening conditions in global regions characterised by non-transient factors, in particular state fragility. While Latin America and east/southeast Asia continue to make strong headway, parts of sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia are seeing slow-down and reversal of earlier gains, with increase in absolute numbers of chronically malnourished. Without action, years of progress and generations of children risk being left behind.

For the future, macro-level factors – climate change, population growth, competition for land and water, rising energy costs and falling yields – look set to maintain upward pressure on food prices. At the same time, fiscal space to enlarge social protection, health and nutrition programmes will continue to be constrained in fragile and conflict-affected countries through the global economic slow-down, falling aid receipts, loss of export earnings, and weak domestic GDP growth and revenue.10 Being less equipped to cushion adverse effects, fragile countries are liable to see progress on nutrition halted, unless additional, properly targeted support is forthcoming.

G8 donors have shown increasing interest in the problems of hunger and nutrition in recent years. They have also committed a substantial proportion of their aid budgets to addressing conflict and security in fragile countries and regions.11 All major arguments – moral, equitable, efficient – suggest that they should look closely at maximising the complementarity of their spending in these two areas.

2 This report focuses on acute and chronic malnutrition, described throughout the report as ‘undernutrition’.3 Lancet, 2008.4 IFPRI, 2012; SUN, 2010; Unicef, 2009; de Onis et al., 2000; Kikafunda et al., 1998; Yoon et al., 1997; Victora et al., 2008; Czernichow et al., 2006; Alderman et al., 2006; Kar et al., 2005; Kim, 2004; Alvarez et al., 2003; Robinson, 2001; Osmond & Barker, 2000.5 Sarma, 2011; this amounts to approximately twice the total global aid spend by all donors in 2011-12.6 Horton et al., 2010.7 AfDB, 2012; SUN, 2012; IFPRI, 2012; Whitehall & Kandasamy, 2012; Kandala et al., 2011; Horton et al., 2010; Megeily, 2010; Guha-Sapir et al, 2005; Brennan & Nandy, 2001; Hussein & Herens, 1997.8 Acute and chronic undernutrition overlap in many instances but also occur independently and in highly varying ratios.9 vLautze, 2012; Hendrix & Brinkman, 2012; IFPRI, 2012; Brinkman & Hendrix, 2011; World Bank, 2010; Diaz-Bonilla & Ron, 2010; Bakrania & Lucas, 2009; Wodon & Zaman, 2008; Messer et al., 2001; Ogden, 2000; Cohen & Pinstrup-Andersen, 1999; Hendrickson & Armon, 1998.10 Addison et al., 2011.11 In total, G8 commitments to undernutrition and conflict/security in recent years amount to around USD$66 billion.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 5

April 2013

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

6

Executive SummaryFragile and conflict-affected states (referred to as ‘FCAS’ throughout the report) suffer some of the worst rates of acute and chronic undernutrition in the world. Yet, of 42 FCAS, a minority (16) have, so far, joined the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement. Moreover, those FCAS remaining outside SUN have systematically weaker economic indicators and poorer governance capacity than those now within the movement.

The weight of financial, policy and programmatic attention – particularly in FCAS – is directed at acute malnutrition. Chronic malnutrition, by contrast, remains poorly understood and widely under-addressed in practice by government and partners in many fragile contexts. In many fragile states and conflict situations, donors focus funding on short-run measures that visibly reduce acute suffering and hunger. FCAS governments, meanwhile, prefer to support food measures that mitigate immediate (often urban) threats to social stability. Civil society efforts are hampered by short-term thinking in the policy and financing environment, and the limits to scale within which they operate. These conditions conspire to limit what one might call ‘governance for nutrition’ in many FCAS contexts.

There is little active opposition among non-SUN FCAS to signing up. Instead, commitment appears obstructed by uncertainty and inertia. Absence of clear signals from donors that new resources may be available for nutrition reduces political interest in an area conventionally given quite low priority anyway. Institutional uncertainty about the financial, political and security environment locks partners into a perpetual humanitarian mode of intervention. Evolving beyond known and relatively reliable emergency and short-term funding and implementation relationships is perceived as risky, not only for line ministries but for partners too. This increases the difficulty in achieving cross-government, intersectoral coordination (in particular between core nutrition ministries of health and agriculture) on which a more sustainable, integrated approach to nutrition is founded.

The state of play regarding nutrition in FCAS is inefficient (especially where ‘fragility’ is poorly defined and the problem of ‘insecurity’ is overstated), and liable to render statebuilding and peacebuilding objectives less effective. Ultimately, however well food aid and emergency feeding programmes drive down the immediate problem of hunger, failure to mitigate the chronic, socially-embedded drivers of childhood malnutrition is likely to lead to new generations of young people, biologically disadvantaged from before birth, disadvantaged at school, disadvantaged in the labour market and poorly paid. Those drivers frequently mimic broader horizontal socioeconomic and ethno-political divisions in society, so that the systematic exclusion that fosters chronic undernutrition in the most vulnerable and marginalised groups simultaneously builds the risk of a new cycle of instability, violence and conflict.

SCALING UP NUTRITION (SUN)12

‘Scaling Up Nutrition’ (SUN) is a global movement launched in 2010 by the UN Secretary General, to enhance action on undernutrition. It builds on the findings of the Lancet Nutrition Series, advocating a package of interventions which includes both ‘direct’ nutrition (largely through the health system), and ‘nutrition-sensitive’ programming (including agricultural production and food security, as well as education, water and sanitation amongst others). It advocates a stronger focus on undernutrition in general, in particular maximising the ‘window of opportunity’ (associated with preventing irreversible damage to the child) through pregnancy to 2 years of age. SUN is founded on the principle of member state sovereignty – insofar as joining SUN is a decision taken by the country concerned. In principle, all countries are eligible to join SUN, without selection.

As of 30 January 2013, 33 countries had signed up to SUN. We use the term ‘signed up’ to denote the act of submitting the demarche-style letter from a country’s head of state or mandated ministry or agency to the Geneva SUN Secretariat. Clearly, signing up is a relatively simple procedure. This research takes signing up (or not) as a marker of political and policy discussions and processes – regarding the importance attached to key human welfare matters like nutrition – going on within government in fragile and conflict-affected states. In this sense, signing or not signing up to SUN constitutes a useful starting point for investigating those discussions and process which, collectively, constitute an important dimension of governance.

12 http://scalingupnutrition.org/

Using quantitative analysis covering 42 SUN and non-SUN FCAS, and qualitative field-based country case studies,13 this research project aims to answer three central questions:

• How is SUN working in fragile and conflict-affected countries? • What are the factors that appear to support or obstruct FCAS engagement with SUN? • What may be needed to strengthen FCAS engagement with SUN and with undernutrition more generally?

The research does not evaluate the impact of joining SUN – that remains to be done in years to come. But it starts from the premise that the approach and package of interventions promoted by SUN are derived from best available evidence, and that it is political commitment and institutional capacity that determine progress.

The research was designed to understand SUN and the problem of nutrition in the context of state fragility and conflict. It quickly became apparent, however, that how FCAS governments respond to the problem of undernutrition and the SUN agenda offers an insight into how governance works in such countries, when confronted with a particular problem and corresponding opportunity.

In particular it highlights some of the tensions generated by nutrition, within government and with partners, over the appropriate balance between humanitarian and development modes of analysis and action. It highlights the distinct variation in government functionality and the nature of insecurity within the FCAS category, encouraging a closer look at what we mean by fragility and how far the category should be allowed to determine overarching policy in such environments. And it highlights the political and policy struggles in many FCAS over prioritising productive sector spending (such as health and agriculture) under heavy competition from dominant security and macroeconomic policy agendas.

Recommendations are directed first and foremost at donors, but include action that can – and should – be taken complementarily by other partners working on nutrition in FCAS. The central propositions – increasing the resource incentive to take action on undernutrition, and constructing resource mechanisms that encourage government ownership and cross-sectoral working – are closely interconnected.

The overarching observation is that undernutrition in FCAS continues to be seen, fundamentally, as a problem of acute malnutrition, whose solution lies in an increase in the provision of food. If SUN is, truly, endorsed within the international community as a better approach, donors and technical agencies partnering with government in FCAS should be more consistent in adopting and promoting the SUN model of integrated action on nutrition – action which addresses both acute and chronic undernutrition, by incorporating interdependent interventions in health, food security and agriculture.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 7

April 2013

13 These case studies – for Sierra Leone, DR Congo and Afghanistan, with additional analysis of Yemen and Pakistan – are made available in the full research report, from May 2013.

Children in Afghanistan face some of the most difficult conditions in the world. This school started in 2005 and educates 2,700 students a day in two shifts in only 10 classrooms. Children learn computer skills, hygiene and family awareness.© 2012 Paul Bettings/World Vision

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

8

1a There is major variation in awareness and understanding of SUN between FCAS

1b Prevalence of undernutrition does not drive government action in FCAS

2 FCAS with poor economic indicators are less likely to join SUN. Weak confidence in additional resources dilutes political interest in/ commitment to the nutrition agenda

3 FCAS with weaker governance are less likely to join SUN. Emphasis on sector-specific humanitarian treatment of mainly acute undernutrition inhibits intersectoral and inter-ministerial incentives to collaborate

2.1 Donors should collectively signal new funding for integrated nutrition in FCAS

2.2 Donors should design an appropriate mix of mechanisms by which to provide new nutrition resources and support, to build government ownership and governance capacity (including, inter alia, general budget support, pooled funding, programme support, and pragmatic technical support to ministries)

2.3 Donors, UN agencies and NGOs should use their networks to promote nutrition as a core strategy in FCAS with multiple dividends in peacebuilding and long-term conflict risk reduction, economic recovery (livelihood security) and economic development (productivity and growth)

3.1 Donors, UN agencies and NGOs should promote nutrition as a strategy for economic development, institutionally endorsed by the relevant finance ministry with power to broker coordination of line ministries, with emphasis on building the bilateral relationship between health and agriculture

3.2 Partners should support domestic non-state actors (CSOs, business) to lobby for nutrition investment, emphasising accountability (governance) and efficiency (growth)

4.1 Partners should identify and invest in key areas which support SUN viability, fitted to FCAS country context, including e.g. role of agriculture in peacebuilding; political commitment to equitable basic healthcare; presence of REACH or similar technical alignment mechanism; quality of public finance management; sympathy of finance institutions to nutrition agenda etc. in order to build national capacity to lead nutrition strategy

4 Prevailing insecurity in an FCAS does not preclude effective government. Partners should proactively seek ways to build government and governance from early stages of intervention even in conditions of instability and ongoing conflict

4.2 Partners should establish a long-term strategy coordination mechanism from the earliest phase of intervention in FCAS, separate from emergency fora

4.3 Operational partners (UN and I/NGOs) should design and lobby for longer-term integrated nutrition projects, with government and donors in FCAS, as part of a combined short/long-term post-conflict strategy

1.3 Donors and partners should agree additional stimulus for FCAS to adopt SUN model (whether or not joining SUN)

1.1 SUN should secure more coherent endorsement of its model with strategic donor and UN partners

1.2 Donors and partners should promote the SUN model more strongly and consistently throughout FCAS

Finding Recommendation

Key findingsThe main body of this report presents, in summary form, the principal findings of the research.

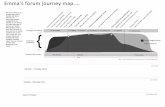

Finding 1: Prevalence of Undernutrition does not Predict Accession to SUNThere was no statistical correlation between the level of undernutrition in a population and the likelihood of its government signing up to SUN (graph 1).

This is not necessarily a surprising finding in and of itself. After all, although FCAS have relatively high rates of malnutrition, their responsiveness and accountability to popular issues are stereotypically classed as weak. While one might hope that population rates of wasting above 20% and stunting as high as 60% would galvanise urgent priority within government, the evidence here suggests that the numbers do not, on their own, drive political or policy response in FCAS. Add to this the finding that civil society and public activism does not appear to influence FCAS chances of joining SUN, and the viability of relying on domestic forces within FCAS countries to drive SUN accession – or indeed better action on nutrition – becomes doubtful.15

SUN is founded in the principle of being a country-led movement.16 The problem is that according to this finding, in the absence of additional (probably external) encouragement, some FCAS are likely to remain outside SUN at least for a foreseeable period. This could be viewed as an unfortunate but acceptable outcome. The danger is that SUN then becomes, albeit unintentionally, part of a process of backing winners, with some better-performing FCAS taking on the SUN agenda, and others not. Assuming that SUN is effective, this then leads to a rise in nutritional inequity, as the SUN countries improve and non-SUN FCAS stagnate or fall behind.

In any case, country case studies show donors and external agencies taking an extremely active role with government on SUN in some instances, suggesting that external influence is not only acceptable but instrumental.17 The issue is not the validity of external influence, but the fact that the level of partner activism on SUN varies dramatically from one FCAS country to another. Yemen and Sierra Leone received both high-level political encouragement from donor countries, and

14 The descending lines indicate rates by country between SUN and non-SUN FCAS. When we added non-FCAS SUN signatories to the graph, as a control comparison for the SUN/non-SUN analysis, we found that, although they had marginally lower rates of undernutrition, all three country groups were broadly similar.15 The relationship between civil society activism and FCAS governments’ likelihood of joining SUN is probably more complex than this suggests. The indicators used are not necessarily the best ones, though they are the ones most consistently available. Further research would be useful, not least since analysis of other global movements (for example access to antiretrovirals and humanitarian disarmament) shows the substantial potential benefits of well-coordinated civil society support. International and domestic civil society in FCAS may be more heavily engaged in emergency projects, limiting capacity and political space to push governments in the broader domain of policy advocacy. 16 Dr David Nabarro, the Secretary General’s Special Representative on Food and Nutrition Security and SUN Secretariat Coordinator clearly states that SUN is non-selective. In itself, this seems the right position to take, both because a global movement encounters identity problems when it becomes exclusive, and because donors’ use of ‘good governance’ selectivity among FCAS has created some extraordinarily counter-rational policy positions with deeply unfortunate effects (see, e.g. McGillivray, 2006). However, this research argues that more proactive support from partners does not necessarily compromise the country-led ideal.17 The principle of state sovereignty and of ‘country-led’ processes like SUN does not demand a hands-off approach. Indeed, partners sometimes use arm’s length intergovernmental propriety to camouflage political squeamishness. The idea that donors and technical agencies (let alone a globalising private sector) do not exercise major influence on government thinking in FCAS is nonsensical. The key is not to try avoiding influence, but to ensure that influence is positive with regard to accepted norms (such as the desirability of reducing global hunger) and workable with regard to an adequate understanding of context.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 9

April 2013

Graph 1: Prevalence of Stunting (moderate & severe) in SUN and non-SUN FCAS14

highly-aligned technical support across the major UN agencies. Pakistan has received considerable encouragement, though with less clear outcomes given the current governmental gap in Islamabad. By contrast, promotion and awareness of SUN in both DR Congo and Afghanistan were negligible and in some quarters noticeably ambivalent. It would be helpful to understand these differences since, whilst they may reflect legitimate policy on the part, for example, of donors, they may also reflect a new version of familiar preferential behaviour towards some FCAS to the exclusion of others.18

It is undoubtedly the case that, in some places, a combination of genuinely humane (or at least economically enlightened) government and powerfully-articulated public demand will result in a kind of home-grown nutrition movement.19 But the implication of this finding is that other FCAS are going to need additional stimulus to take action.20 In the long-run, such stimulus should involve building public awareness of nutrition and civil society organisation around the issue (the policy demand-side). But in the near-term, the finding suggests that stimulus should be applied to government itself (the policy supply-side), in particular in the areas of resource mobilisation and institutional coordination.

Across the country case studies, there was virtually no evidence of active opposition to the SUN movement.21 What we see, rather than opposition, is uncertainty and inertia – partly political, partly institutional.22 Stimulus – implicitly provided in part by actors external to government – does not necessarily undermine country leadership. Government – particularly in FCAS – embodies political and sectoral contests among elites, factions and ministerial institutions. Nutrition is an aetiologically, programmatically, financially and hence politically complex field of policy and planning. Stimulating technical understanding and political commitment, and supporting institutional arbitrage among key actors, can be a valuable and legitimate element of relations between the international community, country partners, and government. More broadly, actively promoting government ownership and capacity to govern in critical areas of social policy and programming should be a clearer and stronger part of partners’ strategy in supporting FCAS conflict resolution and recovery.

The quantitative analysis and country case studies point to two areas in which additional stimulus to government should be directed: first, clearer signals (primarily from donors) regarding availability of resources to support SUN implementation in specially challenging FCAS conditions; second, stronger support to government in FCAS in ways that foster ownership of and capacity to lead an integrated nutrition agenda, as envisaged by the SUN movement (whether or not they subsequently decide to join SUN).

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

10

18 See, e.g. OECD, 2011. Aid allocations – and donor engagement – across FCAS continue to reflect geopolitical interests rather than proportional response to objective need.19 Many of the current FCAS SUN signatories would probably be described as being ‘high-performing’ in the FCAS category.20 ‘Stimulus’ here does not refer to the kind of predominantly fiscal manoeuvres seen in high-income countries.21 Possibly Pakistan, where sovereignty issues may have inspired opposition to what is perceived as unwarranted intrusion.22 Lack of leadership in and ownership of a national nutrition agenda can be major barriers to government engagement.

Baby Safia is checked with a MUAC band at a World Vision nutrition project, just outside Herat, Afghanistan.©2012 Chris Weeks/World Vision

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 11

April 2013

Finding 2: Better Economic Conditions Significantly Improve Likelihood of FCAS Accession to SUN The quality of economic performance predicts the likelihood of a FCAS government signing up to SUN. Long-run positive trend in GDP growth improves the chances, while higher debt-to-GDP ratio strongly reduces them (graph 2). This finding, again, is intuitive. Where FCAS governments are struggling to protect fiscal space for perceived national priorities (amongst which nutrition is often relatively low), greater scarcity of resources will weaken attention to concerns classed as lesser.

In the absence of economic confidence domestically, availability of donor support is likely to have a significant influence over both the prioritisation of nutrition and the credibility of national nutrition strategies and plans. Support can take various forms, from general budget support, through pooled funding or programme support, to technical assistance. Finding the right composition of resources and support can help shape incentives for government to take greater ownership of the issue, but will likely need to be context-specific in design.

In the main, government institutions were unable to see any clear signals regarding the likelihood of new funding following on from accession to SUN.23 Major donors – including those leading on nutrition in some countries – have so far been notably non-committal with regard to new commitments. Even in Sierra Leone, where government has gone beyond accession to inter-ministerial budgeting and planning, major donors on nutrition do not expect their own agencies to produce new SUN-specific support.

“Other donors are not so interested in nutrition here”Donor, Sierra Leone

Rather, the dominant donor view appears to be that SUN accession creates a ‘brand’ (marking a government out as actively engaged with the problem of undernutrition), on the basis of which future requests for support may be treated with special consideration. The expected sequence is that FCAS governments join SUN, and associated new domestic resources to undernutrition then crowd in donor support. This ‘articulated’ approach to resource mobilisation will not necessarily appeal to some FCAS governments – especially those who believe that the problem is mainly acute malnutrition; that acute malnutrition is already covered by humanitarian agencies; and that government priorities, in any case, lie more centrally in re-establishing security and engendering macroeconomic reform.

Moreover, from a FCAS government perspective, there are good reasons to view sceptically a donor promise of ‘jam tomorrow’. Donors are tightening their belts in the aftermath of the global downturn. Commitments to UN Resolution 2121 of 0.7% GNI in Official Development Assistance (ODA) are being reconsidered (and even where the commitment is honoured, contraction in OECD economies will mean a reduction in what the percentage actually entails).24

Donor commitments have rarely, as a rule, equalled what they give. Aid to fragile and conflict-affected countries has been especially uneven and volatile for decades.25 That situation is given an additional layer of complexity as major donors seek to revisit existing rules on ODA for military, defence and security spending.26 Whilst this report recognises the legitimate concern

23 The principle of state sovereignty and of ‘country-led’ processes like SUN does not demand a hands-off approach. Indeed, partners sometiFrom a strategic point of view, the secretariat suggests that SUN is not designed to be a new financing mechanism [personal communication, SUN Secretariat, 8 March 2013]. That said, the SUN Strategy, 2012-15 acknowledges that: ‘the success of SUN will depend on the preparedness of countries and donors to provide the necessary financial resources’.24 UK aid, for example, was expected to be 4-5% lower than forecast prior to the period of recession (OECD, 2010).25 See, e.g. OECD, 2011; McGillivray, 2006. Volatility is estimated to reduce the value of aid by up to 15%.

Graph 2: Debt-GDP ratio, GDP growth rate, and inflation in SUN and non-SUN FCAS

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

12

for security in FCAS contexts, it suggests that investments (including aid and FCAS governments’ own spending) should demonstrate a balanced approach to spending on security relative to spending on basic services as complementary elements of conflict resolution and peacebuilding. Over time, as active conflict declines, partners in FCAS countries should expect to see a shift in the ratio of government spending on defence and basic services in favour of the latter, and to plan for this from the early post-conflict period onwards.27

Although some donors have enhanced aid to fragile states and regions in recent years, reduction in access to ODA is expected in many FCAS. In Afghanistan, for example, USAID projects a very substantial fall in country allocation from 2014 on with the draw-down of military presence.28 After 2009, African FCAS were predicted a real-terms decline of USD$368m in aid receipts.29 It is estimated that over half (58%) of the expected downturn in aid will fall on FCAS countries, with countries of lesser geopolitical interest falling further behind in terms of donor attention.30 At the same time, FCAS countries will see domestic resources deteriorate sharply.31 In these circumstances, governments operating under heightened stress are unlikely to view potentially costly but unsupported commitments to areas like nutrition as a good deal. That makes the viability of SUN in FCAS less certain, without significant change in the resource environment.

Uncertainty over future resources not only reduces political engagement. It increases the disincentive for individual institutions and ministries to engage in the longer-term, intersectoral mode of working that SUN envisages. In a climate of political and financial uncertainty, ministries are less likely to risk income and institutional capital on unproven and politically complex intergovernmental collaborations. Instead, they show a distinct preference for fortifying existing, reliable, even if short-term and sectorally-confined humanitarian funding relationships. Weakness in cross-government coordination is noted as one of the most significant obstacles to SUN in country case studies.

26 Reuters, February 13, 2013 http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/02/21/uk-britain-economy-budget-idUKBRE91K00G20130221. The UK is by no means alone in this thinking. The US, the Netherlands and Germany are among major OECD donor countries producing similar ODA policy positions (OECD, 2010; Camack et al., 2006; Macrae & Harmer, 2004). For further discussion of this, see Finding 4, p.20, below.27 In many FCAS contexts, spending on defence and security remains relatively high, often outstripping spending on basic services. Non-SUN FCAS spend a larger amount on defence and security, relative to basic services, than SUN FCAS. This either indicates that SUN FCAS governments feel more confident in their chances of avoiding return to conflict (and hence the need for larger defence budgets) or that, notwithstanding those concerns, they view basic services as, in themselves, a legitimate area of expenditure in the peace- and statebuilding process. 28 One estimate was a reduction of up to 80% of current aid over the next 2-3 years. Contrast this with planning for a US-Afghanistan strategic partnership from 2014 to 2024 which forecasts allocations of USD$82 billion to military assistance for the country, and USD$9.7 billion for ‘economic development’ annually in the period from 2013 to 2017 (Katzman, 2013).29 OECD, 2010.30 OECD, 2011.31 IMF, 2009 in Bekrania et al., 2009. African economies are expected to see national growth fall from 5% to 1.7% as a result of the global crisis, though more recent data suggest some areas of recovery in the region.

A mother feeds her undernourished child in a health centre in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.© 2012 Sylvia Nabanoba/World Vision

Finding 3: Governance is the most powerful predictor of accession to SUN Governance is, by several powers of magnitude, the most statistically significant predictor of FCAS countries joining SUN (graph 3).32 SUN FCAS (red) score systematically higher than non-SUN FCAS (blue) on the Country Policy and Institutional Analysis (CPIA) index used by the World Bank.33

Graph 3: Average CPIA Score, SUN and non-SUN FCAS, 201134

Yet, in spite of international commitments (in particular those around harmonisation and support to country-led systems and processes embodied in Paris, Accra and Busan), supporting governance in FCAS continues to be a challenge.35 Governance programmes frequently focus on centralised state legitimacy processes (such as elections, public finance management and corruption) and somewhat scatter-gun support to promoting

civil society activism. There is often considerably less attention to governance as the extension of state through local systems and services at the periphery. While funding can be channelled through government via sector ministries, the policy priorities for how money is spent are still very often guided by donors’ preferences rather than the priorities of government. Emphasis on programmes and projects suggests tactical use of deployable (often non-state) actors more than systemic investment in government as a core actor the whose visibility throughout the national space is understood to be axiomatic to the state-society compact.36

“Aid for nutrition does not follow Busan principles”Government, DR Congo

The proportion of aid provided as ‘General Budget Support’ (GBS)37 can be used as a proxy for donor confidence in and commitment to recipient government leadership and governance capacity. Across FCAS, the GBS proportion hovers between 2 and 4%. In 2011, 0.28% of Afghanistan’s and 2.6% of DR Congo’s aid was delivered as GBS (none of it provided by bilateral donors). In Sierra Leone, a healthier 12% of total aid was received as GBS, 72% of which came from bilateral agencies.38 Whilst one might hope to see a modest upward trend in the volume of GBS (as donor confidence builds), between 2007 and 2011, the GBS trajectory for many FCAS countries was volatile and unpredictable. To be clear, GBS is not the only mode of resource support donors can consider to strengthen nutrition action in FCAS (especially where

32 ‘Governance’ is measured, in the first instance, using the World Bank’s CPIA dataset.33 The y axis indicates average CPIA score by country; SUN and non-SUN states are arranged as two groups along the x axis.34 Interestingly, the pattern of the graph holds steady when we add in non-fragile SUN signatories. Non-fragile SUN countries score much the same as fragile SUN countries. This appears to suggest that the definition of ‘fragility’ is somewhat unstable, used differently by different classifying institutions, principally donors. That opens the way for political distortion of what is meant by fragility, and to whom it is applied. That should worry donors and recipient countries alike. 35 See Macrae & Harmer, 2006: ‘Perhaps one of the most significant shifts emerging […] in situations of protracted crisis is the increased interest in engaging with populations, if need be circumventing the state to deliver assistance’.36 The Busan Principles (article 19) commit partners to use ‘country systems’ wherever possible, to be transparent in cases where it is decided it is not, and to engage with government counterparts in such instances, to establish what would be required to move to country systems use. SUN and Busan are identical with regard to support for country-led process, and by implication, prioritising government capacity and governance. It is surprising therefore that, as of February 2013, only 3 FCAS countries were signatories of both movements.37 GBS is unearmarked finance that flows from donor to national treasury and from there to national priority allocations without necessary allocation-specific reporting obligations. 38 The intention here is not to argue that there is a systematic difference in proportion of aid given as GBS between SUN and non-SUN FCAS. While we note that Kenya (9.3%), Rwanda (8.2%) and Burundi (5%) are all signatories, we also note that Uganda (SUN) received just over 2% of aid as GBS in 2011, 100% of which came from bilateral donors, while Liberia (non-SUN) received 1.6%, none from bilaterals. For Pakistan (non-SUN) and Yemen (SUN), in 2011, no aid falls under GBS.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

14

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

4.5

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

CPIA Score, SUN FCAS & Non-SUN FCAS

SUN FCAS Country Governance Scores Non-SUN FCAS Country Governance Scores

CPI

A S

core

(to

tal,

2011

there are legitimate concerns over accountability). Programme-level finance, as well as pooled funds and pragmatic technical support can all form part of a mix that aims to increase government ownership. The key is that the country-specific mix demonstrates more convincingly that donors want to work through, and so strengthen, government in FCAS.

Uncertainty about FCAS governance and the viability of working with or through FCAS government extends into the nutrition agenda too. In 2008, the Lancet Nutrition Series (LNS) noted that: ‘maintaining effective national and sub-national nutrition programmes in contexts of political instability or, worse, open conflict, is seen as a major challenge in qualitative studies supporting the SUN movement’. Similarly, in contexts of ‘natural disaster or conflict’, it is suggested that the ‘international nutrition system’ may adopt a direct service provision role, circumventing government which is assumed to be incapacitated or uncooperative. More recently, in its 2010 strategy paper, SUN acknowledges that ‘In many, but by no means all, [situations of state fragility] it is not feasible to develop or implement country-owned strategies’.39

“We are starting to work more closely with government, but we don’t have a clear plan.”

UN, Afghanistan

This finding suggests that the approach to nutrition that SUN envisages requires greater engagement with FCAS governments and governance. Governance, however, is a notoriously overused term, often poorly defined or applied in vague generalisations. In order to understand in more detail what aspects of governance distinguish non-SUN from SUN FCAS, we broke down their overall CPIA scores into 16 sub-categories of performance, comparing sub-category averages between the two groups. We found that the most significant differences in governance performance between SUN and non-SUN FCAS lay in four areas:40 ‘fiscal policy’, ‘business regulatory environment’, ‘equity of public resource use’, and ‘social protection and labour’. Of these, three – fiscal policy, equity of public resource use, and social protection and labour – correspond strongly to observations from the country case studies.41

BUILDING INTRA-GOVERNMENT COORDINATION IS KEY TO NUTRITION AND GOVERNANCE IN FCAS

We know that bringing nutrition within the ambit of government priorities, and building genuine coordination between key nutrition-related ministries, is vital to SUN.42 We also know that government institutions, in general as well as in the country case studies, find this kind of collective planning and responsibility extremely hard to achieve in practice, while partners are often reluctant to engage with sensitive intra-governmental policy and fiscal bargaining processes.43 Low scores among non-SUN FCAS in the area of ‘fiscal policy’ point to difficulties within these governments in negotiating shared priorities, including for nutrition.44

A basic barrier to intersectoral coordination is the absence of a clear, shared concept of the problem.45 SUN envisages what might be called an ‘integrated nutrition model’, acting on both acute and chronic malnutrition through a combination of health and non-health interventions. In many FCAS however, as noted earlier, acute malnutrition and its treatment are seen as the priority.46 Malnutrition programmes are run predominantly by or through humanitarian agencies, often working directly under donors and in most cases weakly supporting the development of national governance capacity. Although interventions such as Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) are commonly rolled out through the

39 Bryce et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2008; SUN, 2010.40 Measured as sub-categories in which the differential between SUN and non-SUN FCAS average scores total or exceed 0.6. This is a somewhat arbitrary cut-off line, but constitutes 10% variance of the total available score in each area.41 ‘Business regulatory environment’ is the sub-category that was less clearly represented in the field. It is possible that this reflects a chance association, or that it reflects an association to do with FCAS governments’ capacity to control commercial aspects of national nutrition policy, perhaps particularly to do with regulation of food fortification. 42 FAO, 2012; SUN, 2012; Sarma, 2011; DFID, 2011; Levine & Chastre, 2011; Harper et al., 2010; Linnemayr et al., 2008; Black et al., 2008; Hunt, 2005; Zere & McIntyre, 2003; Webb & Lapping, 2002; Latham & Beaudry, 2001; de Onis et al., 2000; Delpeuch et al., 2000; Kikafunda et al., 1998; Bouvier et al., 1995; Mora et al., 1992.43 See, e.g., Lautze et al., 2012; Goodhand & Sedra, 2010; DESA, 2010. See, also, the Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium(SLRC) research programme of the Overseas Development Institute: ‘Political and governance constraints to policy implementation are a critical piece of the puzzle’ in the performance of public services. http://www.odi.org.uk/ 44 Whilst a core index of fiscal policy is debt-to-GDP ratio, a wider interpretation looks at the process of allocating public finance within and between productive sectors. 45 Exacerbated by a technical and policy language that can, at best, be described as opaque. 46 Harper et al., 2010; SUN, 2010; Spiegel et al., 2010; Oniang’o, 2009; Bryce et al., 2008; Flores, 2004; Young, 1999.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 15

April 2013

Ministry of Health, such programmes have not, characteristically, relied on or tried to build governance capacities, including cross-sectoral vision and collaboration.47

“Aid has focused on acute malnutrition up to now. Now we want a change”Government, DR Congo

A disproportionate focus on acute malnutrition in FCAS has either undermined or failed to strengthen concept and capacity within government in the emerging policy discourse of ‘food and nutrition security’.48 We see this in Afghanistan, DR Congo and Yemen. Sierra Leone is the only country case study in which genuine efforts to integrate acute and chronic malnutrition appear to have changed the political and policy balance. Donors and technical agencies (primarily the four UN partners in the Renewed Efforts Against Child Hunger (REACH) project – Unicef, WHO, FAO and WFP) have a key role to play in promoting an integrated model of nutrition, rebalancing the terms of the debate. To play this role, though, they need to decide whether they are, at institutional level, committed to the SUN model and, if so, to make it the centrepiece of their policy discussions and negotiations consistently at field level with their FCAS government counterparts.

We see that, where donors have led high-level contact, and where technical agencies have been closely aligned around an integrated nutrition model, FCAS responses have been positive (Sierra Leone and Yemen, for example).49 We also see that each, on its own, renders less clear outcomes. In Pakistan, absence of a negotiating partner in Islamabad has complicated approaches. In DR Congo and Afghanistan, notwithstanding some attempts at higher-level contact, SUN has been engaged primarily at the technical level of national nutrition programmes, which then struggle to negotiate the integrated model upwards to the ministerial and political domains.

“REACH enabled SUN to take off. It got people thinking together” UN, Sierra Leone

Political and technical endorsements are clearly necessary but not, in and of themselves, sufficient. Between them, they may eventuate the development of a national strategy or plan. But the prospect of the national plan being implemented collaboratively and effectively by different parts of government depends on complex institutional processes of negotiation that are likely to continue regardless of formal agreements to work together. Even in a strong SUN accession country like Sierra Leone, contest over share of access to resources under the National Food and Nutrition Security Plan is expected to continue between the two principal ministries – health and agriculture. Similar contests are emerging or predicted in Yemen and DR Congo. In Afghanistan the conjoined National Nutrition Action Framework is in place, but has been slow to eventuate sectoral action. In Pakistan, best estimates suggest that major efforts should be confined within the health sector, in part because the politics of agriculture and land are too contentious to touch. Ultimately, governance support to advance SUN in FCAS countries needs to address the likely inter-ministerial tensions that, almost inevitably, arise where scarce resources and the political capital of positive outcomes are to be shared. A clear message from the research is to focus support on the bilateral relationship between health and agriculture.50 But perhaps more importantly, the implication is that a government mechanism is likely to be required to broker between these ministries. Not infrequently, high-level endorsement by President or (more often) Vice-President/Prime Minister is seen as the most effective brokering mechanism in the case of intra-government log-jams. But we also find that senior politicians are wary of stepping into ministerial disputes (especially where ministries are allocated to different, not always friendly factions as part of an ongoing attempt at political settlement). Technical cadres, on the other hand, rarely have the political clout to discipline contending ministers.

47 See e.g. Carpenter et al., 2012; Nixon, 2009.48 See e.g. Spiegel et al., 2010. The emphasis on acute malnutrition may be compounded in FCAS countries which are heavily focused on improving their MDG performance. In many fragile states, >5 child mortality (MDG 4a) occupies top priority. In this research, FCAS joining SUN showed considerably better long-term trend in reducing >5 child mortality. An MDG orientation drives attention to acute malnutrition. The risks inherent in this are a) that it privileges short-term interventions with less interest in underlying, structural issues and b) it rationalises investments in nutrition which are timebound to 2015,the end date of the MDGs framework.49 The REACH initiative involving the four major nutrition agencies (Unicef, WHO, FAO and WFP) is now established in 12 countries, with several prospects on the horizon. Of these 12, all are also signed up to SUN (half of them being FCAS). Of three prospective countries, one joined SUN in early 2013, another is expected to join imminently; both are also FCAS. 50 Rather than pursuing the conventional multi-sector, multi-stakeholder approach which involves amassing as many vaguely relevant ministries as possible at meetings on the assumption that presence denotes commitment.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

16

“Each programme and department is looking for its own resources – it’s about survival”

UN, DR Congo

Country case studies suggest that support from a supra-sector ministry (e.g. finance, economy, planning) can provide helpful institutional authority to coordinate, arbitrate and even discipline line ministries (particularly with incremental aid accountability requirements). This suggests that advocacy for SUN should ensure early and active engagement with ministerial institutions responsible for the national budget process.51 In Sierra Leone, strong engagement by the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development has created an institutional environment in which commitments to intersectoral cooperation can be maintained and monitored, and disputes can be managed without the agenda itself being frozen or sidelined within government. Advocacy in support of SUN should aim to establish nutrition as a core strategy for economic development, and a legitimate policy issue for finance, budget and planning ministries to adopt and promote. Much current emphasis goes to the health sector, understandably. But this research suggests that the finance and economic development sectors are important targets.

Following on from this, the boxes below describe policy and governance challenges in key nutrition sectors, focusing on ‘equity in resource allocation’ (health) and ‘labour and social protection’ (agriculture) as areas in which to build governance for nutrition in non-SUN FCAS.

51 Acknowledging that this can be complex – in Sierra Leone, it is the powerful Ministry of Finance and Economic Development; in DR Congo, fragmentation of finance, budget and planning makes identifying the centre of fiscal power more difficult.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 17

April 2013

A woman and child at a health centre in Herat, Afghanistan.© 2012 Paul Bettings/World Vision

BUILDING EQUITABLE HEALTHCARE SUPPORTS THE EFFICIENCY OF NUTRITION INTERVENTIONS

SUN implies significant growth in the functionality of the health sector in participating countries.52 In some instances, service delivery and access needs to increase from lows of 2-10%, reaching 70-80%.53 In many FCAS countries, we know that health systems are damaged or simply underinvested. Yet the recurrent and sizable costs of building a sustainable system of healthcare create major barriers for both donors and government.54 Health aid remains uneven and often inadequate. Ranges run from 15% of total aid receipts in Sierra Leone through 10% in Yemen (almost entirely multilateral), to 6% in DR Congo, and 3.4% in Afghanistan.55 Individual donor commitments are in some cases worryingly small. USAID’s budget for health in Afghanistan constitutes less than 1% of its total country allocation. Alternatives for financing health care include outsourcing service provision to non-state providers and instituting cost recovery on some health goods and services.56

The response of both donors and government to weak health services is to finance a somewhat unwieldy compromise of state and non-state service providers, at least in the short-term humanitarian phase.57 But ‘short-term’ as often as not morphs into a long-term model, persistently bypassing government, and failing to strengthen health systemically.58 Health funding may be coordinated through the ministry of health, but often it remains heavily controlled by donors with regard to where it is spent, on what and by whom.59

There is no necessary objection – aside from ideological ones – to the use of non-state (NGO, private, faith-based) actors in providing health services in FCAS.60 So long as these actors, collectively, are able to provide an agreed and consistent package of services equitably accessible and acceptable across a population, there should be no necessary distinction between non-state and state.61 The problem is that this is not reliably happening in FCAS. Whilst NGO and other contract-based service providers are increasingly managed under a standardised package of healthcare interventions, coverage remains in many cases extremely patchy, tied to short-term humanitarian funding arrangements, and subject to weak or negligible government oversight.

What is missing, in both instances, is an adequate proportion of health funding allocated to supporting government to build and steward the health system. Between 1.9 and 2.8% of total health aid in FCAS goes to investment in ‘basic health infrastructure’; between 1.5 and 2.7% goes to ‘health personnel development’.62 Whoever the service provider turns out to be, building government capacity to oversee the progressive quality and equity of the system is key.63 For this, governance capacity is needed – both centrally and sub-nationally – to understand, plan, monitor and assess service provision, including the package of direct nutrition interventions. When we look at allocation of aid to ‘health policy and administrative management’, however, we find that while in SUN FCAS, one in every three health aid dollars is spent building policy and management capacity, in non-SUN FCAS countries, the ratio is one in ten (graph 4).

52 See e.g. Lutter et al., 2012. The SUN Strategy Paper 2012-15 cites ‘universal access’ to services including health as key. 53 See e.g. Sierra Leone’s National Food and Nutrition Security Strategy, 2012-15.54 Look, for example, at the size of DR Congo.55 Creditor Reporting System, OECD-DAC [accessed 19 March 2013].56 Cost recovery presents a problem for equity and for efficiency in nutrition.57 See e.g. Spiegel et al., 2010.58 Of country crises recorded in the last decade, half have lasted more than 8 years (GHA, 2012).59 Influence of MDG and disease-specific targets on health sector spending was notable in both DRC and Afghanistan. 60 Except insofar as ‘state legitimacy’ depends on popular perception of service provision, distinguishing state employees from non-state contractors. See e.g. Carpenter et al., 2012.61 Major problems associated with delivery of health services by non-state parties (civil society, NGOs, private sector actors) – e.g. coverage and equity, coordination and quality regulation, sustainability and local ownership (Kharas & Rogerson, 2012) – should, in principle, be managed by strong government stewardship. 62 CRS, OECD-DAC, 2011.63 Focusing on the equity aspects of policy and planning functions with regard to the health system in FCAS should be seen as a priority in conflict recovery and peacebuilding. See e.g. Bornemisza et al., 2010.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

18

Improving nutrition will necessarily involve increasing support to the health system. This research does not propose to address the wider issues of universalising healthcare and the tensions of sustainability and equity in health financing options. But it suggests that more support could be provided, in FCAS contexts, to building government capacity to govern the health system. Beyond this, given the sheer scale of health care system strengthening in many FCAS, it may be worth considering a sub-national start for SUN in some contexts.64

PROTECTING SMALL-SCALE FARMING IN AGRICULTURE POLICY CAN SUPPORT BOTH NUTRITION AND PEACEBUILDING

Health remains the centrepiece of most national nutrition strategies, both in terms of the emphasis on direct interventions, and assumed institutional responsibility within government. The danger of a continuing health-centrality is that necessary counterpart sectors are demoted to a second tier of policy.65 In particular, the role of agriculture, food and food security can and should be much more strongly integrated in the global standard of a comprehensive nutrition strategy. The role of agriculture and food has a particular resonance in FCAS, where conflict results in often sharp rises in food insecurity, and where smallholder farming can, in the right circumstances, form the basis of peacebuilding and economic recovery.66 In many FCAS, food security remains a poor cousin to the nutrition agenda in terms of policy priority and investment.67 While direct interventions on food aid and assistance are critical to survival in many FCAS situations, such interventions have been designed primarily to address short-term emergency situations, with less success in building longer-term support food security.68 Evidence suggests that voluminous food aid and distribution programmes, whilst effective in reducing mortality, do not on their own mitigate the underlying problems of undernutrition.69

“Politicians prefer feeding programmes to nutrition” NGO, Afghanistan

Different FCAS countries appear to view the role of agriculture in building (or rebuilding) social stability very differently. In some instances, the rural sector has been seen as key both to demobilising and resettling combatants,

64 For example, DR Congo and Pakistan; see e.g. Van de Walle & Scott, 2009.65 The SUN Update (2012) notes more progress in direct interventions, with challenges to progress on nutrition-sensitive work. This imbalance is rooted in the original LNS research method, see e.g. Bhutta et al., 2008: ‘We excluded several important interventions that might have broad and long-term benefits, such as education, untargeted economic strategies or those for poverty alleviation, agricultural modifications, farming subsidies, structural adjustments, social and political changes, and land reform’.66 The emphasis in the latter case being on recovery of economic viability at household and community levels. 67 It is interesting that there is no code for ‘food security’ under ‘agriculture’ in the OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System (http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=CRSNEW). ‘Food security’ is listed as a co-element of ‘food aid’ under ‘Commodity Aid and General Programme Assistance’. 68 Productive safety net programmes such as in Ethiopia are examples of more sustained, integrated food assistance and security strategy. The problem for many FCAS is that they have limited capacity to fund this kind of social protection.69 See, e.g. Pantuliano, 2007. Large-scale food distribution in Afghanistan over an extended period has not translated into sustained improvement in malnutrition or reduction in chronic food insecurity among especially poor rural households.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 19

April 2013

Graph 4: % of Total Health spend allocated to ‘policy and administrative management’, SUN and non-SUN FCAS

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Av. % Total Health Spend to Health Policy and Management 2011

% spending for ‘health policy and management’, SUN and non-SUN FCAS

SUN FCAS Non-SUN FCAS

SUN FCAS

Non-SUN FCAS

% o

f Tot

al H

ealth

Exp

endi

ture

and as a foundation for reconstructing the livelihood viability of conflict-affected communities. But in most FCAS, public investment in agriculture remains relatively small (below 10% of national budget, more often below 5%), as does aid to the sector, and support to small-holder farmers remains ambivalent.70

Aid and investment that prioritises small-scale household and cooperative production and marketing systems can see relatively quick and effective return to stable communities after fighting has died down. Sierra Leone is notable for having incorporated return to agriculture as a core part of its early post-conflict recovery strategy.71 By contrast, demobilisation and reintegration efforts in DR Congo following the peace agreement in 2002 demonstrate a remarkable ambivalence towards a ‘return to agriculture’ model, with fully one half of combatants reinserted in the reformed army, the other dispatched with largely ineffective support to resettle in their communities of origin. It is not at all clear that there is an agricultural strategy for settlement (or perhaps more accurately reversion to livelihood development) among rural Afghans. Current food security interventions are small-scale in most cases, and dwarfed by military investments in securing the peace.72 Given the predominance of rural population dependent in one form or another on agriculture for livelihood in many FCAS, SUN may provide a lens through which governments and partners can look again at the role agriculture can and should play combining food security, nutrition and peacebuilding.73

The emphasis of agricultural investment in a number of FCAS contexts is either explicitly or implicitly on increasing productivity and production for commercialisation. In Sierra Leone and DR Congo, national agricultural strategies appear to favour expansion of cash cropping to increase export earnings as a contribution to national economic recovery and growth.74 Production for export is predicted to be, by some way, the largest sector of agricultural growth to 2020 in Afghanistan. The problem here is that an investment paradigm that favours larger-scale production and ignores smallholders, may well actively undermine the livelihoods – and hence nutritional conditions – of poor rural farming households.

Even where national agricultural strategy focuses explicitly on the condition of small-holder farmers – the vast majority of farming households in most FCAS – the dominant approach is to support increased production for sale, on the assumption that increased household income will underwrite better nutrition. Clearly increasing the income of poor households can improve nutritional status. But it is also clear that increasing poor rural household reliance on markets for nutrition can increase their vulnerability as net buyers. More evidence is needed before a strongly market-oriented strategy is allowed to dominate alternatives such as increasing households’ direct consumption of own produce as a way of improving nutrition.75

70 Of the case studies, in 2011, Sierra Leone has the highest proportion of aid allocated to agriculture (10%), followed by Afghanistan (8.3%), Pakistan (2.7%), DR Congo (1.4%) and Yemen (0.7%).71 This was the case also in Liberia.72 In very few instances are fundamental issues of land ownership and agrarian reform directly addressed. Where land rights issues are perceived to be too politically complex to touch (as in the case of Pakistan), emphasis on food security is re-marginalised in favour of safer sectors such as health.73 The World Bank (2010): concludes: ‘It is not possible to reduce conflict in fragile and poor countries on a sustained basis without significant new investment and partnerships in key areas of agriculture and rural development’.74 In spite of evidence suggesting that FCAS governments should focus on social rather than macroeconomic policies as a first line strategy for conflict resolution and peacebuilding (Collier, 2002). 75 This is not a zero-sum proposition. Agricultural policy that reflects both macroeconomic aspirations and the immediate and sustainable welfare of the population needs to support both export and local production (del Castillo, 2012).

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

20

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02 21

April 2013

Finding 4: Insecurity does not Rule Out Effective GovernmentMuch of what has been proposed so far by this research is, of course, predicated on a sufficient degree of security in FCAS countries. Clearly, what constitutes ‘sufficient security’ (or ‘state fragility’) determines much that can be done in these environments. Insecurity has become an increasingly powerful discourse in the approach of partners to FCAS situations, limiting what they themselves are prepared to do (in particular how far they are willing to extend themselves into, and hence how much they directly know about, uncertain terrain), and limiting, sometimes drastically, expectations of FCAS government in terms of leadership and capacity.76

76 See e.g. Duffield, 2007.77 Pachon, 2012; OECD, 2010; DFID, 2009; Government of the Netherlands, 2008; Zoellick, 2008; Camack et al., 2006; Macrae & Harmer, 2004; OECD, 2004.78 ‘It is impossible to strengthen overall governance without attention to the security sector’. (Government of the Netherlands, 2011).79 OECD, 2010.80 GHA, 2012. 81 Rubenstein, 2011; Government of the Netherlands, 2011; OECD, 2010; Unicef, 2009; IDS, 2009; Justino, 2009; Brinkerhoff, 2005; Wagstaff & Watanabe, 1999; Brentlinger et al., 1999; Aldoori et al., 1994.82 OECD, 2010. Donors’ own funding mechanisms can be instrumental in locking in a humanitarian mode. Half of all humanitarian aid is extended over longer-term timeframes in protracted crises rather than ceding to developmental funding.

Partners in FCAS countries increasingly operate under a ‘security first’ paradigm, in which military stabilisation and re-establishment of state, primarily through ‘hard’ security interventions, is accompanied by sporadic and largely unsustainable humanitarian approaches to basic service delivery.77 Security is constituted as the ‘necessary precondition for longer-term sustainable development’.78 The proportion of aid allocated to ‘security’ has increased significantly faster than other elements of aid spending in the last decade, including after the economic downturn. Security sector spending increased by 61% after 2006-07, 86% of that rise from bilateral donors.79 Aid to ‘governance and security’ rose 165% between 2002 and 2009, rising from 6.9% to 12.2% of total spending over that period, and totalling USD$16.6 billion in 2009.80 Longer-term investments in government, governance and structural capacity to delivery national scale services, in this paradigm, tend to be seen as the consequence of re-established stability and security, rather than as a strategy for building peace in themselves.81

“Everything here is about security and politics. Donors want security.”UN, Afghanistan

In a practical sense, insecurity now limits – often quite severely – what partners believe is possible in some FCAS countries. It locks in a short-term, crisis management, humanitarian mode of thinking and action (which, in the absence of largely unavailable field-based evidence to the contrary, becomes the self-reinforcing shared mantra of donors, government and implementing partners). Donors prefer to retain shorter-term grant relationships and simpler goods and services delivery interventions to minimise exposure to unforeseen performance failures.82 Line ministries work to protect vertical (or ‘stovepipe’) relations with their sector donors and technical agencies, rather than building horizontal relations with other ministries. Perpetuation of humanitarian modes maintains a marginalisation of government as a coherent, independent actor in the systemic provision of welfare, undermining or attenuating its leadership. In many fragile and conflict-affected countries, however, insecurity based on actual threat of violence is often confined to relatively small geographical areas, while a comprehensive assumption of government dysfunction or incapacity is rarely borne out by reality. Fragility and conflict do not necessarily denote the breakdown of effective government. With this in mind, we should ask whether the ‘security first’ mode of operation unnecessarily neglects, or actively undermines, opportunities to strengthen governance in ways which could foster greater governmental responsibility for leadership on the kinds of social welfare and productive sector systems and services identified as key to nutrition and SUN.

World Vision UK –Research Report UK-RR-CH-02

April 2013

22

83 WGI provides a useful counterpoint to CPIA, being derived from a range of source datasets (rather than in-house World Bank assessments), and including perception data showing what government looks like from a popular perspective including, importantly, public perceptions of effectiveness in the provision of basic services. 84 Notwithstanding some bumpiness, accounted for mainly by Haiti and Niger.

In order to explore this, we compared CPIA data on governance in FCAS against Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) for both ‘effectiveness of government’ and ‘political stability and absence of violence’.83 We found, first of all, that governance in FCAS countries (CPIA) corresponds well with ‘effectiveness of government’ (WGI, graph 5).84 This strengthens confidence in the validity of governance measures.

When we compared the same governance scores with ‘political stability and absence of violence’ (WGI), however, there was no correspondence between the two (graph 6).

On the face of it, this might suggest that instability and violence are not necessarily the bar to good governance and effective government that they are imagined to be under the ‘security first’ worldview. This is an interesting finding when we consider evolving policy in FCAS, though one that requires further validation.

Having established that governance (CPIA) and government effectiveness (WGI) track one another, but that neither is associated with prevailing conditions of instability and violence, we decided to look at how effectiveness of government and presence of instability/violence affect FCAS chances of joining SUN. We find that, whilst there is a distinct positive association between the effectiveness of an FCAS government and its engagement with SUN (graph 7), there is no systematic difference between SUN and non-SUN FCAS countries related to the ‘absence (or presence) of violence’ (graph 8).

Graph 5: Governance (CPIA) and ‘Effectiveness of Government’ (WGI) in SUN and non-SUN FCAS, 2011

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

2.00

1.50

1.00

0.50

0.00

-0.50

-1.00

-1.50

-2.00

CPIA & WGI/Effectiveness of Government, SUN and Non-SUN FCAS

SUN

Ken

ya

SUN

Uga

nda

Non

-SU

N

SUN

Sri

Lan

ka

SUN

Nig

er

SUN

Mak

awi

SUN

Sie

rra

Leon

e

SUN

Bur

undi

Non

-SU

N K

irib

ati

Non

-SU

N

Non

-SU

N T

ogo

Non

-SU

N C

AR

Non

-SU

N

Non

-SU

N C

ote

Non

-SU

N

Non

-SU

N C

had

Non

-SU

N E

ritr

ea

Non

-SU

N

Non

-SU

N

Non

-SU

N S

omal

ia

... ... ... ... ... ... ...

CPIA/IRAI

Effectiveness of Government (WGI, 2011)

Graph 6: Governance (CPIA) and Political Stability/Absence of Violence (WGI) in SUN and non-SUN FCAS, 2011

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

2.00

1.50

1.00

0.50

0.00

-0.50

-1.00

-1.50

-2.00

CPIA & WGI/Political Stability, Absence of Violence, SUN and Non-SUN FCAS

SUN

Ken

ya

SUN

Uga

nda

Non

-SU

N B

osni

aH

SUN

Sri

Lan

ka

SUN

Nig

er

SUN

Mal

awi

SUN

Sie

rra

Leon

e

SUN

Bur

undi

Non

-SU

N K

irba

ti

SUN

Hai

ti

Non

-SU

N L

iber

ia

Non

-SU

N A

ngol

a

Non

-SU

N G

uine

a

Non

-SU

N C

ongo

Non

-SU

N G

uine

a

Non

-SU

N C

omor

os

Non

-SU

N S

udan

SUN

Zim

babw

e

Non

-SU

N

Non

-SU

N

Non

-SU

N S

omal

ia

... ... ... ...

CPIA/IRAI

Political Stability and Absence of Violence Trend 2000-2011 (WGI)

Finding 4 is, at this stage, suggestive. But it points to an interesting possibility – that government can remain more effective than commonly imagined, even under conditions of instability, violence or conflict. This would suggest that the current ‘security first’ paradigm may not always be necessary or indeed helpful – that there may be entry points to improving governance/government independent of reductions in ambient violence and securitisation of the state at the centre. It may be possible to engender important improvements in governance, government capacity and behaviour – for example relating to nutrition – earlier than is often assumed in the process of emerging from conflict into post-conflict, peacebuilding and statebuilding.85