Research Article Sleep, Fatigue, and Functional Health in...

Transcript of Research Article Sleep, Fatigue, and Functional Health in...

Hindawi Publishing CorporationSchizophrenia Research and TreatmentVolume 2013, Article ID 425826, 7 pageshttp://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/425826

Research ArticleSleep, Fatigue, and Functional Health in Psychotic Patients

Flavie Waters,1,2 Neepa Naik,2,3 and Daniel Rock1,2,3

1 School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, The University of Western Australia, Perth, WA 6009, Australia2 Clinical Research Centre, Graylands Hospital, North Metropolitan Mental Health, Private Bag No. 1,Claremont Perth, WA 6910, Australia

3 Clinical Applications Unit, Graylands Hospital, North Metropolitan Mental Health, Perth, WA 6910, Australia

Correspondence should be addressed to Flavie Waters; [email protected]

Received 9 March 2013; Accepted 10 April 2013

Academic Editor: Markus Jager

Copyright © 2013 Flavie Waters et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License,which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This study sought to examine the association between sleep, fatigue, and functional health in psychotic patients. Participantsincluded 93 psychotic inpatients (𝑛 = 67 with schizophrenia) who completed the Chalder Fatigue Scale (ChFS), the FatigueSymptom Inventory (FSI), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the SF36 Health Survey. Patients were classified onthe basis of their performance on sleep and fatigue measures: 60% reported significant levels of fatigue and 67% significant sleepdisturbances. 28.4% reported both, suggesting that fatigue and sleep dysfunctions do not necessarily cooccur. A closer examinationof patterns showed that fatigue was only related to qualitative aspects of sleep and not quantifiable aspects of sleep disturbances.The results also showed that functional health was the lowest in patients with high levels of fatigue, compared to patients with sleepproblems only or patients with neither symptom. A regression analysis further showed that the size of the contribution of fatigueonto functional health was twice as much as that of sleep dysfunctions. In conclusion, the results show that (i) dissatisfaction withsleep—and not sleep itself—is related to fatigue symptoms and that (ii) fatigue is particularly detrimental to functional health,regardless of the presence of sleep dysfunctions.

1. Introduction

Fatigue is a condition characterised by persistent weaknessor exhaustion and a combination of symptoms that featureself-reported impairments in some of the following: impairedattention and concentration, headaches, unrefreshing sleep,and/or musculoskeletal pain [1]. Fatigue is an experientialstate typically diagnosed on the basis of self-reports and isa common complaint in the general population [2, 3]. It isusually associated with middle age, being female, and havinglower education and occupation attainment [4]. Fatigueis common in psychiatric conditions such as anxiety anddepression (25–36%) [5–7] and in chronic medical condi-tions such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis,diabetes, and viral infection [8–12]. Fatigue worsens withincreasing physical disease severity [10] and is independentof medication suggesting that medication itself is not respon-sible for fatigue.

Studies of fatigue in patients with psychotic disorderssuch as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are currently

lacking. Yet several reasons support an investigation intofatigue symptoms in these individuals. First, the functionalimpairments associated with fatigue include considerableimpairments and disability [13, 14] pointing to fatigue as animportant target for treatment. Second, the cooccurrence offatigue and psychiatric symptoms such as depression is linkedto greater functional impairments than when it occurs alone[15, 16], suggesting that fatiguemay aggravate current existingpsychiatric conditions. Third, indirect evidence supportsan association between fatigue and severe mental illness.Environmental or neurobiological traumas during criticalperiods are common vulnerability factors for both fatigueand psychiatric disorders and are increasingly scrutinisedas a pathway for the development of psychosis and fatigue[16, 17]. Finally, there ismuch overlap in affected brain regionsbetween fatigue and psychotic disorders. The prefrontalcortex and the anterior cingulate play an integrative role inarousal, drive, motor control, and executive control and aredysfunctional in both psychiatric disease and fatigue. Givensuch overlap, one might therefore expect greater rates of

2 Schizophrenia Research and Treatment

fatigue-like symptoms in individuals with severe psychiatricdisorders. The first aim of the present study was thereforeto investigate the symptoms of fatigue in patients withpsychosis, as assessed using questionnaires commonly usedto assess fatigue in community, primary care, and clinicalsettings: the Chalder Fatigue Scale [18] and the Fatigue ScaleInventory [19].

The second aim of this studywas to assess the relationshipbetween fatigue and sleep, as measured with the PittsburghSleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire [20], in patientswith psychosis. Sleep dysfunctions are a common clinicalfeature of severe psychiatric disorders. Sleep complaintsinclude increased time to fall asleep, decreased total sleeptime, and increased sleep awakening [21–23] and are linked tosignificant functional and psychosocial impairments, includ-ing decreased coping, greater distress, and increased risk ofsuicide [21, 24, 25]. Poor sleep has been estimated to accountfor 24% of the variance in quality of life in schizophrenia [21].

The relationship between sleep dysfunctions and fatiguein psychiatric illness has not yet been explored. Some suggestthat sleep dysfunctions and fatigue could be intrinsicallyrelated [26]. Evidence presented in support includes thefinding that fatigue is a common complaint in individualswith sleep disorders [27], and that these conditions often co-occur [28]. Sleep and fatigue also share phenomenologicalfeatures such as inactivity, tiredness, and daytime sleepi-ness. Furthermore, patients with persistent fatigue (chronicfatigue) report difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep asa primary complaint [26, 29, 30]. However, sleep is a mul-tifaceted concept which includes sleep efficiency, perceivedsleep quality, and impact on daytime functioning [31], andstudies that have examined components of sleep have showedthat fatigue is not relieved by sleep time or efficiency [32], andthat sleep quality is not always associated with fatigue [33].This suggests that the relationship between sleep disturbancesand fatigue is complex, and different patterns of relationbetween sleep and fatigue may arise [33].

The third aim of the current study was to examine therelationship between sleep, fatigue, and functional health inpsychosis. Psychosis is linked to considerable disability, anda better understanding of the factors that contribute to thisdisability can reveal important new treatment options. Asmentioned above, the daily consequences of both fatigue andsleep include impaired daytime functioning and impairmentsin health and functional ability [14], although this relation-ship has not yet been examined in patients with severementalillness. Here, we examined this association with correlationsand group comparisons, enabling an analysis of both linearrelationships and group profiles.

In summary, the aims of the study were to (i) investigatethe symptoms of fatigue in patients with psychosis, (ii)examine the relationship between sleep dysfunctions andfatigue, and (iii) assess the relationship between sleep andfatigue on functional health in this clinical population. Itwas hypothesised that patients would show high levels offatigue and that fatigue would not be directly related to sleepdysfunctions. Finally, it was hypothesised that both fatigueand sleep would be independently linked to poor perceptionsabout health.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants. Participants included 93 psychiatric inpa-tients of Graylands Hospital in Perth, who agreed to partic-ipate in a health survey. Clinical diagnoses were made bypsychiatrists with clinical interviews and comprised axis Imental disorders, predominantly schizophrenia, and bipolar-affective disorder. All inpatients were asked to complete aself-administered health survey,which took approximately 20minutes to complete. Ethical approval was obtained from theNorth Metropolitan Mental Health Human Research EthicsCommittee.

2.2. Measures. The Chalder Fatigue Scale [18] (ChFS) is an11-item questionnaire which assesses physical and mentalsymptoms of fatigue. Scores for both physical (items 1–7) andmental (items 8–11) fatigue can be combined to provide a totalscore. All items were rated using a 4-point scale (0 = “betterthan usual,” 1 = “no more than usual,” 2 = “worse than usual,”3 = “much worse than usual”). A bimodal scale is also used toprovide a validated cut-off score to calculate clinical severity(0 = “better than/no more than usual” and 1 = “worse/muchworse than usual”). Cronbach’s alpha for the ChFS from thecurrent sample was adequate at 0.88.

Fatigue Scale Inventory [19] (FSI) provides an indicatorof the impact of fatigue on daytime functions with 14 items. Itassesses the frequency, severity, daily pattern, and perceivedinterference on quality of life. Four domain scores canbe calculated. The FSI severity compositeis calculated byaveraging four symptom severity scores (Items 1–4), eachusing an 11-point scale (0 = not at all fatigued and 10 = asfatigued as I could be). A perceived interference scale scoreis measured using 7 items (Items 7–11) assessing perceiveddaytime interference from fatigue symptoms. FSI days refersto the number of days of the week participants felt fatigued inthe pastweek (item 12: from0 to 7 days).TheFSI percentrefersto the proportion of each day that respondents felt fatigued onaverage (item 13: 0 = none of the day, 10 = the entire day).Therecommended cutoff for clinically significant cases of fatigueis a score of 3 or greater on the Average fatigue severity item.Cronbach’s alpha for the FSI from the current sample wasexcellent at 0.93.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [20] (PSQI) com-prises 19 self-rated questions designed to measure sleepquality during the previous month and discriminate betweengood and poor sleepers. Domain scores ranged from 0(no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty), which are summedto produce a global score (range 0–21). A global score>5 is suggestive of clinical levels of sleep disturbances. Itassesses seven broad domains: sleep quality, sleep latency,sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances,use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction. Thesecan be aggregated into a three-factor solution [34]: sleepefficiency (comprising of the “sleep duration” and “sleepefficiency” domains), perceived sleep quality (comprising“use of sleep medication”, “subjective sleep quality” “sleeplatency”), and daily disturbances (“daytime functions”and“sleep disturbance”). Cole et al. [34] factors produce morestable subscale scores than the PSQI and reduce the number

Schizophrenia Research and Treatment 3

of measures to be analysed. The PSQI has been validatedin several clinical populations and shows high internalconsistency (Chronbach’s 𝛼 = 0.80) and good constructvalidity [20].

SF36Health Survey [35] is a self-report surveymeasuringdomains of health-related quality of life with 8 scales: physicalfunction, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality,social functioning, role-emotional and mental health. Twosummary measures known as component scores are derived:the physical health component score and the mental healthcomponent score. Each scale is standardized on a 0–100metric, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

3. Data Analysis

For aims 1 and 2, descriptive statistics were used to charac-terise fatigue and sleep, and bivariate correlation coefficientswere used to examine any linear relationship between thesescores. Nonparametric versus parametric analyses were usedaccording to the normality of the distributions. For aim 3,we sought to reduce the number of data variables consistentwith previous analyses [33, 36] by classifying patients intofour groups on the basis of their performance on sleep andfatigue measures. First, z-scores were calculated on eachmeasure, and composite z-scores were created for each ofthe fatigue and sleep scores. In other words, a fatigue scorewas created by averaging individual scores on the FSI andthe ChFS, whereby a sleep score was created from the PSQIglobal score. Second, a median-split approach was used todefine 4 subgroups with elevated/low scores groups on eachof the fatigue and sleep domains: low fatigue and low sleepdisturbances (group 1: “intact”), high sleep disturbances andlow fatigue (group 2: “sleep problems only”), high fatigue andlow sleep disturbances (group 3: “fatigue only”), and highfatigue and high sleep disturbances (group 4: “both sleep andfatigue problems”). This approach allowed a clinical frameof reference for understanding the characteristics of each ofpotential subgroups. The 4 groups were compared on theSF36, PSQI, FSI, and ChFS using multivariate analysis ofvariance (MANOVA) for each domain after controlling forthe variables that were significantly different between groupswith post hoc contrasts to determine which groups weredifferent from each other. As a final analysis, we conductedregression analyses to investigate the relative contribution ofsleep and fatigue to functional health.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics. Table 1 showsthe demographic and clinical characteristics of the partic-ipants. The mean age of the participants was 39.33 years.Patient diagnosis was available for 90 patients and includedschizophrenia spectrum disorders (including schizophrenia,schizoaffective, schizotypal, and delusional disorders) (𝑛 =67), bipolar affective disorder and other mood disorders (𝑛 =8), and other mental and behavioural disorders (𝑛 = 15).Medications data were available for 92 patients. Most (𝑛 =88) of them were on regular antipsychotic medications with

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics for all participant,and scores on the PSQI, ChFS FSI, and SF36 scales.

Variables Mean ± SD (range)Age 39.33 ± 12.08 (19–67)Sex M = 75, F = 18Length of illness (in years) 16.64 ± 11.18Chlorpromazine equivalent dose 913.51 ± 600.19 (66.5–2496)ChFS1 mental fatigue score(max = 12) 5.02 ± 2.29 (0–12)

ChFS2 physical fatigue score(max = 21) 9.14 ± 3.81 (0–19)

FSI2 severity composite 4.30 ± 2.31 (0–9.50)FSI2 perceived interference 3.54 ± 2.50 (0–8.86)FSI2 days 3.55 ± 2.65 (0–7)FSI2 percent 3.54 ± 2.91 (0–10)PSQI3 daily disturbances factor 2.35 ± 1.38 (0–5)PSQI3 sleep efficiency factor 1.17 ± 1.59 (0–6)PSQI3 perceived sleep quality factor 3.10 ± 2.07 (0–8)PSQI3 total score 6.62 ± 3.80 (0–17)SF364 mental health 57.22 ± 20.44 (3–100)SF364 physical health 61.14 ± 21.26 (12–98)SF364 total score 59.93 ± 20.45 (14–99)1TheChalder Fatigue Scale [18], 2The Fatigue Scale Inventory 1998 [19], 3thePittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [20], and 4SF36 Health Survey [35].

numbers of concurrent ATP formulations per person rangingbetween 1 and 4 (𝑛 = 38, 37, 10, and 3 resp.). Antipsychoticswere converted into chlorpromazine equivalents (Table 1).Thirty patients were on regular antidepressant medicationsand 19 patients were on benzodiazepines.

Complete fatigue data were available for 91 patients.Table 1 shows that, overall, patients reported significant levelsof fatigue. On the ChFS, the total mean fatigue score was3.72 (3.57 SD). 59.8% of patients scored 3 or greater on thebimodal scale, a validated cutoff for clinical fatigue cases. Onthe FSI, 73.6% of patients scored 3 or greater on the “averagelevel of fatigue” item, pointing to clinically significant levels offatigue. Patients reported that they suffered from fatigue, onaverage, 3.5 days per week. About diurnal aspects of fatigue,25.8% reported no consistent daily pattern of fatigue, and25.8% reported fatigue being worse in the morning. 13.5%reported fatigue being worse in the afternoon, another 13.5%in the evening.Only 1/5 of patients (21.3%) reported not beingfatigued at all.

Analyses of demographic and clinical variables showedthat the only significant correlation was between chlorpro-mazine equivalents and “FSI percent” (rho = −0.22 and 𝑃 =0.041), showing that increasing antipsychotic dosages werelinked to decreased number of days of the week participantsfelt fatigued. There were no other significant correlationsbetween ChFS or the FSI and age, chlorpromazine equiv-alents and length of illness, and no statistically significantdifferences based on gender or diagnosis (schizophreniaversus other diagnosis) (𝑃 > 0.08).

4 Schizophrenia Research and Treatment

Complete PSQI data was available for 81 patients(Table 2). Consistent with previous reports, 66.7% of thecurrent cohort scored above 5 on the PSQI total score,demonstrating clinically significant levels of sleep problems.Correlation analyses showed significant associations betweenthe PSQI daily disturbances factor and chlorpromazineequivalents (rho = −0.22, 𝑃 = 0.05), suggesting that increas-ing antipsychotic dosages were linked to a reduction in inter-ference from sleep problems. There were no other significantcorrelations with age or length of illness (𝑃 > 0.50). Similarly,therewere no significant differences based on sex or diagnosis(𝑃 > 0.14).

Complete data on the SF36 was available for 88 patients.Age and length of illness were significantly correlated withthe SF36 mental health and total scores (all rho < 0.05).Length of illness was also significantly correlated with SF36physical health. These results suggest that increasing age andillness duration were linked to worse perceived health. Malesreported significantly better health than female participants(Wilks 𝜆 = 0.91, F(1,86) = 2.96, 𝑃 = 0.037), but there wereno other effect of diagnosis or chlorpromazine equivalentdosages (all 𝑃 > 0.12).

4.2. Group Classification on the Basis of Sleep and FatigueScores. Table 2 shows the composition of the four subgroupscategorised on the basis of their scores on sleep and fatiguemeasures. 26 patients (32.1% of the total sample) showedneither sleep nor fatigue problems (“intact” group : group 1);13 patients (16.0%) had “sleep only” problems (group 2), 19patients (23.5%) “fatigue only” (group 3), and 23 (28.4%)“both” (group 4). Table 2 shows that the groups did not differin age (F(3,79) = 0.646, 𝑃 = 0.588), gender (𝜒2 = 5.42,𝑃 < 0.14), chlorpromazine equivalent doses (F(3,75) = 0.985,𝑃 = 0.405), or length of illness (F(3,76) = 0.72, 𝑃 = 0.544).

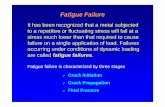

SF36 scores were then examined as a function of the4 groups classified on the basis of sleep/fatigue scores. A4 (groups) × 3 (SF36 mental and physical scores and totalhealth) GLM analysis was conducted, showing significantgroup differences Wilks 𝜆 = 0.74, F(3,73) = 2.51, 𝑃 =0.01, and partial 𝜂2 = 0.095. Between-subjects effects showedthat: First, group 4 (“both sleep and fatigue problems”)had significantly lower scores on all SF36 domains (greaterhealth problems) compared to groups 1 and 2 (“Intact” and“Sleep problems only”) (𝑃 < 0.004). second there were nosignificant differences between groups 4 and 3 (“Both” and“Fatigue only”). third, group 1 (“intact”) reported significantlybetter physical health (greater SF36 scores on physical health)compared to all the other groups.The analyses were repeatedcontrolling for age and gender, and the same results emerged.

Results in Table 2 can also be summarised as follows.Groups 3 and 4 both showed the worse health outcomes.Group 4 (“both”) had a 36.5% decrease in SF36 total scorewhen compared to group 1 (“intact”), while group 3 (“fatigueonly”) was linked to a 19.7% decrease in SF36 total scorecompared to group 1. By contrast, group 2 (“sleep problemsonly”) had very similar scores to group 1 (M = 66.50 versusM = 69.75).

Intact groupSleep problems only

Fatigue problems onlyBoth fatigue and sleep problems

SF36

body

pai

n

SF36

gene

ral h

ealth

SF36

men

tal h

ealth

SF36

phys

ical

func

tion

SF36

role

emot

iona

l

SF36

role

phy

sical

SF36

soci

al fu

nctio

n

SF36

vita

lity

80.00

75.00

70.00

65.00

60.00

55.00

50.00

45.00

40.00

35.00

30.00

Figure 1: SF36 domain scores for the 4 sleep/fatigue groups.

Figure 1 presents a visual representation of the 4 groups’pattern of performance across the 11 subdomains of the SF36.The “intact” group performed best across all domains ofhealth, and was closely followed by group 2 (“sleep problemsonly”). Groups 3 and 4 (“fatigue only” and “both”) showednoticeably lower health scores. Group 4 (“both”) showed theworst performance of them all in all domains except physicalfunctions. Overall, social functions and vitality were SF36domains that were most impacted in the “both” and “fatigueonly” groups, while physical aspects of health (body pain,general health, and physical functions) were the least affected.

4.3. Regression Model for Quality of Life. A regression modelfor predicting the factors best contributing to functionalhealth was conducted using the SF36 total score as thedependent variable. The predictor variables used to build themodel were derived by testing FSI, ChFS, and PSQI domainscores individually against SF36 total scores in regressionsand selecting only the variables showing significant associa-tions. From these analyses, sex, PSQI daily disturbances, andFSI total score were selected as the independent variablesin the regression model. The model produced an adjusted 𝑅squared value of 0.41, which was significant: F(3,71) = 18.01,𝑃 < 0.000, showing that 41% of the variance in SF36 totalscore was predicted by these independent variables. The betavalues for the variables are shown in Table 3. SF36 total scoreshowed a significant negative associationwith sex (𝛽=−10.56,𝑃 = 0.02), FSI total score (𝛽 = −4.46, 𝑃 = 0.000), and withPSQI daily disturbances (𝛽 = −2.86, 𝑃 = 0.045). This showsthat sex had the largest impact on functional health, followedby fatigue, which was in turn larger than the impact of sleepdisturbances.

Schizophrenia Research and Treatment 5

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for the four groups classified on the basis of sleep and fatigue scores.

Group 1“Intact group”(𝑛 = 26)

Group 2“Sleep problemsonly” (𝑛 = 13)

Group 3“Fatigue problemsonly” (𝑛 = 19)

Group 4“Both sleep andfatigue problems”(𝑛 = 23)

Post hoc

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SDGender (M/F) 23/3 9/4 18/1 17/6 n.s.Age 38.42 12.68 36.85 9.54 41.72 12.55 37.17 10.72 n.s.Chlorpromazine equivalents (mg) 999.24 634.14 1069.23 652.44 903.01 541.54 753.55 524.13 n.s.Length of illness 17.12 12.52 13.76 11.47 18.76 11.73 14.69 8.97SF36 mental health subtotal 67.42 18.25 64.42 14.94 53.72 16.84 44.70 20.08 4 < 1, 2SF36 physical health subtotal 70.79 22.74 68.25 16.56 55.39 16.77 50.65 18.74 4 < 1, 2, 3SF36 total score 69.75 19.23 66.50 16.54 55.94 17.32 48.43 18.82 4 < 1, 2

Table 3: Beta values and significance levels of predictor variables.

𝛽 Std. error Sig.Sex −10.56 4.44 0.02FSI total score −4.46 0.88 0.000PSQI daily disturbances −2.86 1.40 0.045

4.4. Association between Fatigue (FSI, ChFS), Sleep (PSQI),and Functional Health (SF36). To examine for linear associ-ations between sleep problems and fatigue symptoms, corre-lations were conducted between FSI/ChFS fatigue and PSQIdomain scores. There were significant correlations betweendomains of fatigue and general dissatisfaction about sleep.All FSI measures (severity, interference, percent, days) werelinked to both PSQI daily disturbances, and perceived sleepquality (all rho< 0.006), andChFS physical fatiguewas linkedto PSQI daily disturbances (rho = 0.30, 𝑃 = 0.007). Bycontrast, PSQI sleep efficiency (sleep-related disturbances)was not correlatedwith any of the fatigue scores (all𝑃 > 0.15).

Next, we examined for associations between sleep,fatigue, and health measures. All three SF36 domains wereall significantly, and negatively, correlated with all ChFSand FSI measures and with PSQI daily disturbances (all𝑃 < 0.007). SF36 mental health was also correlated withPSQI perceived sleep quality (rho = −0.294, 𝑃 = 0.012).No association was found between PSQI Sleep Efficiencyand SF36 scores. Overall, these results demonstrate thatfunctional health tends to worsen with increasing fatigueand dissatisfaction with sleep. The analyses were repeatedusing partial correlations, controlling for age and gender, butoverall significance remained unchanged.

5. Discussion

The current study sought to investigate fatigue in patientswith psychosis and to examine the association betweenfatigue, sleep, and functional health.

A number of findings emerged. First, almost 60% ofpatients (59.8%) reported clinically significant levels offatigue as measured with the ChFS, and 3 out of 4 (73.5%)experienced daytime interference associated with fatigue(FSI severity composite score ≥3). Such high prevalence of

fatigue symptoms is comparable to studies of patients withchronic health conditions such as arthritis, breast cancer,and primary Sjogren syndrome [8, 37–39]. There was noassociation between fatigue and age, sex, length of illness,or diagnosis, although a significant association was revealedbetween chlorpromazine equivalents and the proportion oftime felt fatigued in the past week (FSI percent domain).This supports studies showing positive symptomatic effect ofantipsychotics on fatigue [40].

Second, 67% of patients showed significant levels of sleepdisturbances, underscoring previous findings demonstratingpervasive sleep abnormalities in this clinical sample [23, 41].This study also showed a link between PSQI daily disturbanceand chlorpromazine equivalents dosages. This replicates ourprevious finding that increasing antipsychotics dosages werelinked to better sleep [23], although this previous studyalso showed that antipsychotic medications only accountedfor a relatively small proportion of the variance (8%) andtherefore cannot account for abnormal sleep patterns in thispopulation.

Third, fatigue and sleep dysfunctions cooccurred in lessthan a third of participants (28.4%), with a significantproportion reporting sleep problems in the absence of fatigue(16%) or fatigue only in the absence of sleep dysfunctions(23.5%).These findings support the conclusion that sleep andfatigue symptoms may be, at least in part, independent [33].A close examination of patterns of association provided fur-ther clues regarding their relationship. The analyses showedthat fatigue was only related to qualitative aspects of sleepsuch as general dissatisfaction and sleep complaints (dailydisturbances, and perceived sleep quality). By contrast, therewas no association between fatigue and more quantifiableaspects of sleep disturbances (PSQI sleep efficiency, contain-ing measures of sleep duration, and sleep efficiency). Thecurrent pattern of association between fatigue and subjectivesleep complaints provides a parsimonious explanation forthe mixed findings in the literature. Studies using objectivemeasures of sleep have failed to show a link with levelsof fatigue [32, 33], while questionnaire studies have moreconsistently demonstrated a link between self-reported sleepquality and fatigue [6, 27, 29]. Overall, this body of evidencepoints to the following tentative conclusions: (i) there appearsto be a close association between subjective sleep complaints

6 Schizophrenia Research and Treatment

and symptoms of fatigue, but (ii) sleep-related disturbancesmay not be directly linked to the experience of fatigue. Inother words, dissatisfaction with sleep—and not sleep itself—is related to symptoms fatigue. However, only studies usingobjective measures of sleep such as polysomnography canfully evaluate these conclusions.

Fourth, the current study demonstrated that the presenceand severity of fatigue were particularly detrimental to func-tional health, regardless of the presence of sleep dysfunctions.Health was remarkably lower in both groups of patients withhigh levels of fatigue (group 4 showing both fatigue andsleep problems and group 3 with fatigue problems only).Interestingly, the profile of individuals with sleep problemsonly was hardly different from that of “intact” patients (withneither fatigue nor sleep problems). Our regression analysesfurther showed that significant contributors of functionalhealth included gender, followed by fatigue and sleep. Fur-thermore, the size of the contribution of fatigue was twiceas much as that of sleep dysfunctions, highlighting fatigueas an important target for interventions in patients withpsychosis. These findings in a psychotic sample underscorethe conclusions of Fortier-Brochu and colleagues [33] onindividuals with insomnia that show that fatigue appearsassociated with greater impairments in health-related qualityof life.

Interestingly, the effects of fatigue were particularlyprominent on mental (i.e., vitality), general, and socialaspects of functional health. By contrast, the physical aspectsof health were relatively unaffected, consistent with the ideathat fatigue is primarily a psychological condition.

The study had limitations. This study did not haveinformation regarding the severity of clinical symptoms dueto the lack of symptom measures in the survey instruments.The lack of symptom data made it difficult to examine thepotential link between the negative/deficit syndrome andfatigue in psychosis. Both phenomena share several fea-tures, including problems withmotivation, social withdrawn,and diminished responsiveness; however there are uniqueidentifying features that differentiate negative symptomsfrom fatigue. For example, blunted effect is a characteristicand prominent feature of negative symptoms that is notcommonly linked with fatigue. In addition, fatigue symptomsare commonly seen in association with depressive cognition,depressedmood, and sleep dysfunctions, while these featuresare not related specifically to negative symptoms. Overall,the phenomenological differences between negative symp-toms and fatigue suggest these experiences may be, at leastpartially, distinct, although the similarities are intriguing andshould be pursued in future studies.

Other limitations include the fact that the study wasconducted using psychiatric inpatients, and therefore theresults might not be fully representative of psychotic individ-uals who live in the community. Another limitation was theuse of self-reports to assess fatigue. Fatigue, however, is anexperiential state traditionallymeasuredwith questionnaires.The questionnaires used in this study are commonly usedin the literature, and the reliability and consistency of thescales, as measured with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, wereadequate to good, indicating that this method of assessing

fatigue in our sample was valid and reliable. In addition, ourcurrent finding about the relationship between fatigue andhealth is in line with evidence from both community andclinical samples, supporting the validity of the results.

In conclusion, we believe this is the first demonstration ofsymptoms of fatigue in psychotic patients and link with sleepdissatisfaction. Importantly, fatigue particularly impacted ina significant way on functional health and well-being. Giventhat fatigue plays such a prominent role in the functionalhealth of patients, much can be gained by clinicians increas-ing the focus of their assessment and interventions on fatigue.

References

[1] K. Fukuda, S. E. Straus, I. Hickie, M. C. Sharpe, J. G. Dobbins,and A. Komaroff, “The chronic fatigue syndrome: a compre-hensive approach to its definition and study,” Annals of InternalMedicine, vol. 121, no. 12, pp. 953–959, 1994.

[2] T. Pawlikowska, T. Chalder, S. R. Hirsch, P. Wallace, D. J. M.Wright, and S. C. Wesely, “Population based study of fatigueand psychological distress,” BritishMedical Journal, vol. 308, no.6931, pp. 763–766, 1994.

[3] A. David, A. Pelosi, E. McDonald et al., “Tired, weak, or inneed of rest: fatigue among general practice attenders,” BritishMedical Journal, vol. 301, no. 6762, pp. 1199–1202, 1990.

[4] R. R. Taylor, L. A. Jason, and S. C. Jahn, “Chronic fatigueand sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of psychi-atric disorders in a community-based sample,” PsychosomaticMedicine, vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 896–901, 2003.

[5] S. B. Harvey, M. Wadsworth, S. Wessely, and M. Hotopf, “Therelationship between prior psychiatric disorder and chronicfatigue: evidence from a national birth cohort study,” Psycho-logical Medicine, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 933–940, 2008.

[6] N. Watanabe, R. Stewart, R. Jenkins, D. K. Bhugra, and T.A. Furukawa, “The epidemiology of chronic fatigue, physicalillness, and symptoms of common mental disorders: a cross-sectional survey from the second British National Survey ofPsychiatric Morbidity,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, vol.64, no. 4, pp. 357–362, 2008.

[7] P. Manu, D. A. Matthews, and T. J. Lane, “The mental health ofpatients with a chief complaint of chronic fatigue. A prospectiveevaluation and follow-up,” Archives of Internal Medicine, vol.148, no. 10, pp. 2213–2217, 1988.

[8] C. T. T. Lwin, M. Bishay, R. G. Platts, D. A. Booth, and S.J. Bowman, “The assessment of fatigue in primary Sjogren’ssyndrome,” Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, vol. 32, no.1, pp. 33–37, 2003.

[9] S.Wessely, T. Chalder, S. Hirsch, P.Wallace, andD.Wright, “Theprevalence andmorbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatiguesyndrome: a prospective primary care study,” American Journalof Public Health, vol. 87, no. 9, pp. 1449–1455, 1997.

[10] V. Metta, K. Logishetty, and P. Martinez-Martin, “The possibleclinical predictors of fatigue in Parkinson’s disease: a study of135 patients as part of international nonmotor scale validationproject,”Parkinson’s Disease, vol. 2011, Article ID 125271, 7 pages,2011.

[11] K. L. Hester, J. G. Macfarlane, H. Tedd et al., “Fatigue inbronchiectasis,” Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, vol. 105, pp.235–240, 2012.

[12] L. P. JJelsness-Jorgensen, T. Bernklev, M. Henriksen, R. Torp,and B. A. Moum, “Chronic fatigue is associated with increased

Schizophrenia Research and Treatment 7

disease-related worries and concerns in inflammatory boweldisease,” World Journal of Gastroenterologys, vol. 18, no. 5, pp.445–452, 2012.

[13] D. Racciatti, V. Gorgoretti, G. Sepede, F. Gambi, and E. Pizzi-gallo, “An Italian study on health-related quality of life andfatigue in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and patientswith chronic HCV virus infection: similarities and differences,”International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology,vol. 24, pp. 673–681, 2011.

[14] P. Skapinakis, G. Lewis, and H. Meltzer, “Clarifying the rela-tionship between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatricmorbidity: results from a community survey in Great Britain,”American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 157, no. 9, pp. 1492–1498,2000.

[15] R. Cairns and M. Hotopf, “A systematic review describing theprognosis of chronic fatigue syndrome,”OccupationalMedicine,vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2005.

[16] R. D. Kocalevent, A.Hinz, E. Brahler, and B. F. Klapp, “Determi-nants of fatigue and stress,” BMC Research Notes, vol. 4, article238, 2011.

[17] R. Yehuda and J. Seckl, “Minireview: stress-related psychiatricdisorders with low cortisol levels: a metabolic hypothesis,”Endocrinology, vol. 152, pp. 4496–4503, 2011.

[18] T. Chalder, G. Berelowitz, T. Pawlikowska et al., “Developmentof a fatigue scale,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, vol. 37, no.2, pp. 147–153, 1993.

[19] D.M.Hann, P. B. Jacobsen, L.M. Azzarello et al., “Measurementof fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of theFatigue Symptom Inventory,”Quality of Life Research, vol. 7, no.4, pp. 301–310, 1998.

[20] D. J. Buysse, C. F. Reynolds III, T. H. Monk, S. R. Berman,and D. J. Kupfer, “The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a newinstrument for psychiatric practice and research,” PsychiatryResearch, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 193–213, 1989.

[21] J. R. Hofstetter, P. H. Lysaker, and A. R. Mayeda, “Quality ofsleep in patients with schizophrenia is associated with qualityof life and coping,” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 5, article 13, 2005.

[22] N. A. DeMartinis and A. Winokur, “Effects of psychiatric med-ications on sleep and sleep disorders,” CNS and NeurologicalDisorders, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 17–29, 2007.

[23] F. Waters, D. Faulkner, N. Naik, and D. Rock, “Effects ofpolypharmacy on sleep in psychiatric inpatients,” SchizophreniaResearch, vol. 139, pp. 225–228, 2012.

[24] M. Pompili, D. Lester, A. Grispini et al., “Completed suicide inschizophrenia: evidence from a case-control study,” PsychiatryResearch, vol. 167, no. 3, pp. 251–257, 2009.

[25] M. Ritsner, R. Kurs, A. Ponizovsky, and J. Hadjez, “Perceivedquality of life in schizophrenia: relationships to sleep quality,”Quality of Life Research, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 783–791, 2004.

[26] R. Morriss, M. Sharpe, A. L. Sharpley, P. J. Cown, K. Hawton,and J. Morris, “Abnormalities of sleep in patients with thechronic fatigue syndrome,” BritishMedical Journal, vol. 306, no.6886, pp. 1161–1164, 1993.

[27] M. Lavidor, A. Weller, and H. Babkoff, “How sleep is related tofatigue,” British Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 8, no. 1, pp.95–105, 2003.

[28] F. Romito, C. Cormio, F. Giotta, G. Colucci, and V. Mattioli,“Quality of life, fatigue and depression in Italian long-termbreast cancer survivors,” Support Care Cancer, vol. 20, pp. 2941–2948, 2012.

[29] R. K. Morriss, A. J. Wearden, and L. Battersby, “The relationof sleep difficulties to fatigue, mood and disability in chronicfatigue syndrome,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, vol. 42,no. 6, pp. 597–605, 1997.

[30] A. Kishi, Z. R. Struzik, B. H. Natelson, F. Togo, and Y.Yamamoto, “Dynamics of sleep stage transitions in healthyhumans and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome,”AmericanJournal of Physiology, vol. 294, no. 6, pp. R1980–R1987, 2008.

[31] C. A. Magee, D. C. Iverson, X. F. Huang, and P. Caputi, “A linkbetween chronic sleep restriction and obesity: methodologicalconsiderations,” Public Health, vol. 122, no. 12, pp. 1373–1381,2008.

[32] A. Sharpley, A. Clements, K. Hawton, and M. Sharpe, “Dopatients with “pure” chronic fatigue syndrome (neurasthenia)have abnormal sleep?” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 59, no. 6,pp. 592–596, 1997.

[33] E. Fortier-Brochu, S. Beaulieu-Bonneau, H. Ivers, and C. M.Morin, “Relations between sleep, fatigue, and health-relatedquality of life in individuals with insomnia,” Journal of Psycho-somatic Research, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 475–483, 2010.

[34] J. C. Cole, S. J. Motivala, D. J. Buysse, M. N. Oxman, M. J. Levin,andM. R. Irwin, “Validation of a 3-factor scoring model for thePittsburgh sleep quality index in older adults,” Sleep, vol. 29, no.1, pp. 112–116, 2006.

[35] J. E. Ware Jr. and C. D. Sherbourne, “The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and itemselection,”Medical Care, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 473–483, 1992.

[36] J. L. Hossain, P. Ahmad, L. W. Reinish, L. Kayumov, N. K.Hossain, and C. M. Shapiro, “Subjective fatigue and subjectivesleepiness: two independent consequences of sleep disorders?”Journal of Sleep Research, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 245–253, 2005.

[37] S. Vargas, W. K. Wohlgemuth, M. H. Antoni, S. C. Lechner, H.A.Holley, andC. S. Carver, “Sleep dysfunction and psychosocialadaptation among women undergoing treatment for non-metastatic breast cancer,” Psycho-Oncology, vol. 19, no. 6, pp.669–673, 2010.

[38] L. Traeger, I. M. Braun, J. A. Greer, J. S. Temel, B. Cashavelly,andW. F. Pirl, “Parsing depression from fatigue in patients withcancer using the fatigue symptom inventory,” Journal of Painand Symptom Management, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 52–59, 2011.

[39] Y. Garip, F. Eser, L. A. Aktekin, and H. Bodur, “Fatigue inrheumatoid arthritis: association with severity of pain, diseaseactivity and functional status,” Acta Reumatol. Port, vol. 36, pp.364–369, 2011.

[40] B. Green, “Focus on amisulpride,”CurrentMedical Research andOpinion, vol. 18, pp. 113–117, 2002.

[41] A. Royuela, J. Macias, J. A. Gil-Verona et al., “Sleep inschizophrenia: a preliminary study using the pittsburgh sleepquality index,” Neurobiology of Sleep-Wakefulness Cycle, vol. 2,pp. 37–59, 2002.

Submit your manuscripts athttp://www.hindawi.com

Stem CellsInternational

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

MEDIATORSINFLAMMATION

of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Behavioural Neurology

EndocrinologyInternational Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Disease Markers

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

BioMed Research International

OncologyJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

PPAR Research

The Scientific World JournalHindawi Publishing Corporation http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Immunology ResearchHindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Journal of

ObesityJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine

OphthalmologyJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Diabetes ResearchJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Research and TreatmentAIDS

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Gastroenterology Research and Practice

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Parkinson’s Disease

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Volume 2014Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com

![JumpingtoConclusionsIsAssociatedwithParanoiabut ...downloads.hindawi.com/journals/schizort/2012/384039.pdfTraining (SCIT) [19, 20], the Maudsley Review Training Program [21] or the](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f8db1eb16f3d9002e2a8bf8/jumpingtoconclusionsisassociatedwithparanoiabut-training-scit-19-20-the.jpg)

![Effect of Olanzapine on Clinical and …downloads.hindawi.com/journals/schizort/2018/3968015.pdfnights.M¨ulleretal.[ ]reportedanincreaseinSE,SWS, andREMsleepaerfour-weekadministrationofolanzapine](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f4abc30d174a336e86b10e2/effect-of-olanzapine-on-clinical-and-nightsmulleretal-reportedanincreaseinsesws.jpg)