ASEAN success and failures Jonathan Lim Jun Hong(12) Ng Hou Shun (16) Teh Zi Tao (27)

Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

-

Upload

jutta-pflueg -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

Transcript of Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 1/22

Refugee protection in ASEANnational failures, regional responsibilities

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 2/22

People's Empowerment Foundation (PEF), November 20101/546 Nuan Chan RoadKlongkum, BungkumBangkok 10230, Thailand

tel./fax: (+66) 29466104e-mail: [email protected]

web: http://www.peoplesempowerment.org

Acknowledgements

PEF would like to thank all who provided information for this report,particularly the refugees and asylum seekers who shared their stories.Special thanks to Ang Chanrith in Cambodia, Abdul Hamid and Abdul Ghaniin Malaysia, and Abdul Kalem, Ven. Son Sinan and Ven. Thach Veasna inThailand for their time and dedication in assisting with interviews. We are

also appreciative of Veerawit Tianchainan, Executive Director of the ThaiCommittee for Refugees (TCR), and Anoop Sukumaran, Coordinator of the Asia-Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN), for their valuable analysisand suggestions.

researched and written by Pei Palmgren

research funded by the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy

cover photo: Rohingya refugees in the Immigration Detention Center,

Bangkok, Thailand / Pei Palmgren

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 3/22

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2

I. INTRODUCTION: NATIONAL FAILURES AND REGIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES 3

II. STATELESS ROHINGYA 4

Excluded and Abused in Burma 5

Squalor and insecurity in Bangladesh 5

“Illegal economic migrants” in Thailand 6

Criminalized and vulnerable in Malaysia 8

III. PERSECUTED KHMER KROM 10

Landlessness, poverty, and human rights abuse in Vietnam 10

Statelessness and insecurity in Cambodia 11

Searching for refuge in Thailand 14

IV. LAO HMONG ON THE RUN 15

Hiding in the jungles of Laos 16

Warehoused in Thailand 16

Forced repatriation 18

V. CONCLUSION: TOWARDS REGIONAL SOLUTIONS 19

VI. RECOMMENDATIONS TO ASEAN 20

1

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 4/22

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Countries in Southeast Asia act as origins, transit routes, and destinations for an increasing number of refugees,asylum-seekers, and other forcibly displaced people from the region and other parts of the world. Fleeing conflict,persecution, and other dire circumstances in their home countries, they are continually left vulnerable to a variety of human rights abuses carried out by both state and non-state actors in multiple countries. Sadly, such refugee

problems are being severely neglected in the context of mixed migration. While regulating the inflows of migrants,governments of popular destination countries lack mechanisms for identifying refugees in need of protection, insteadcriminalizing them along with other undocumented migrants. This has led to the persistent suffering and overallconditions of human insecurity for some of the region’s most vulnerable people.

Considering the failure of individual states to protect the rights of refugees, as well as the cross-border implications of refugee problems, it is time for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to take a lead in developing morefair and effective forms of refugee protection at the regional level. So far, ASEAN has come up short in addressingcurrent refugee problems that require close dialogue and cooperation among several member states and others in theinternational community. The Rohingya, Khmer Krom, and Lao Hmong refugee situations reflect the complexity,diversity, and urgency of such problems. These cases demonstrate several glaring gaps in refugee protection inmultiple ASEAN member states and raise challenges for improved protection at the regional level.

Denied citizenship by Burma’s 1982 Citizenship Law, the Rohingya are a stateless ethnic minority who suffer fromsevere oppression and human rights abuse at the hands of the country’s military regime. Fleeing harsh treatment andconditions, the Rohingya face great dangers while being transported on dilapidated boats from Bangladesh to Thailand(as well as beyond), risking drowning and starvation along the way. Considered illegal economic migrants in Thailand,the Rohingya are subject to refused entry, arrest, prolonged detention and deportation. In Malaysia, Rohingyas alsoconfront a hostile environment characterized by immigration raids and cycles of arrest, detention, and deportation, attimes directly into the hands of human traffickers. Unable to rely on any government to protect their rights, theRohingya are an extremely insecure stateless population in need of regional protection.

The small but growing number of Khmer Krom asylum seekers in Thailand is a manifestation of a larger human rightscrisis existing throughout three countries of Southeast Asia. Persecuted for peacefully demanding their rights to

practice religion and own land, monks and land rights activists have fled southern Vietnam to neighboring Cambodia,where they are promised citizenship as Khmer people. Documents required for citizenship are often difficult to obtain,however, leaving many Khmer Krom stateless yet unable to apply for asylum with the Office of the United Nations HighCommissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Khmer Krom monks who fled persecution in Vietnam are particularly vulnerablein Cambodia, where they are closely monitored by authorities and treated as dangerous dissidents. Many resort toliving in Thailand, deprived of rights and fearing arrest and deportation while waiting on asylum bids.

Thousands of Lao Hmong live in the jungles of Laos, fearing violence and death at the hands of Lao soldiers who havebeen suspicious of the Hmong since their involvement with the CIA and American army during the war in Vietnam.Thousands fled to Thailand beginning in 2005 and were eventually contained in a makeshift camp, where thegovernment denied the UNHCR access on grounds that the Hmong were illegal economic migrants. A smaller group of

Hmong refugees, already recognized by the UNHCR, was arrested in Bangkok and detained for 3 years in the NongKhai detention center. They were eventually granted visas to be resettled in third countries but instead were forciblydeported to Laos along with the thousands of Hmong from the camp. Disturbing reports of coercion and other formsof mistreatment in the Laos resettlement camps have been left unverified due to the highly restricted nature of therepatriation process.

With hundreds of thousands of refugees, asylum seekers, and other forcibly displaced people in Southeast Asia fallingthrough the cracks of national legal and administrative mechanisms inadequate to ensure their rights, it is time for ASEAN to include refugee rights protection on its regional community-building agenda. Alternatives to thecriminalization and detention of refugees, the most vulnerable people in ASEAN, must be found in order to achieve thestated goals of a “people-oriented” regional community. ASEAN and its newly established human rights commissioncan address problems by facilitating multilateral dialogues and actions, including participation of civil society

organizations and direct stakeholders, on the most pressing refugee situations. In particular, a regional agreementidentifying core principles, standards of treatment, and shared responsibility for refugee protection among ASEANmember states can contribute substantially to solutions to refugee problems.

2

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 5/22

I. INTRODUCTION: NATIONAL FAILURES

AND REGIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Several ASEAN countries act as origins, transit routes,

and destinations for an increasing number of refugees,asylum-seekers, and other forcibly displaced peoplemigrating throughout Southeast Asia in search of peaceand human security. People from ethnic minoritygroups continually flee conflict and persecution in Burma(Myanmar), thousands of Muslim civilians have beendisplaced by fighting in the southern Philippines, andmembers of religious minorities have escapedrepression in Vietnam, for example, most seeking refugein nearby countries. In addition, a growing number of refugees displaced by conflicts in such countries as Sri

Lanka, Afghanistan, and Iraq have been arriving inSoutheast Asia to seek asylum or in transit todestinations beyond the region.

Distinct from other migrants, refugees are completelydeprived of rights regularly associated with citizenshipand nationality and face grave dangers in their countriesof origin. Importantly, refugee movements in Southeast Asia are occurring within a regional context of mixedmigration, which includes a diverse jumble of not onlyrefugees but also economic migrants leaving varyingsocioeconomic circumstances at home in search of

improved livelihood prospects elsewhere. Suchmigrants often traverse borders and settle in newlocations through the same means and routes as asylumseekers, making it difficult to distinguish betweenmigrants looking for employment and refugees in urgentneed of protection. Instead, states have lumpedrefugees in the same legal category as otherundocumented migrants, effectively criminalizing themas “illegal” in national immigration frameworks.

Without recognition of the distinct rights of refugees andasylum seekers, governments and their nationalimmigration systems have failed to protect refugees inthe region. Of the ten ASEAN member states, onlyCambodia and the Philippines are state parties to the1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Statusof Refugees and its 1967 protocol, while more populardestination countries lack adequate procedures toidentify and protect refugees. Though ASEAN states arebound by customary international law and obligated touphold the rights stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), including those relating torefugees, government policies and practices have run

counter to these responsibilities, regularly threateningthe human rights and security of refugees and asylumseekers.

Rather than protecting refugees, states in Southeast Asia have been compounding problems by arresting,detaining, and at times dangerously deporting those in

need of protection, in the latter case violating theprinciple of non-refoulement ,1 a cornerstone of international refugee protection. Moreover, thecriminalization of refugees and asylum seekers has leftmany vulnerable to a variety of additional human rightsabuses carried out by corrupt officials, exploitativeemployers, human traffickers and other state and non-state actors throughout the region.

Given the failure of individual states to protect the rightsof refugees, it is now crucial for ASEAN to take a lead in

developing more fair and effective forms of refugeeprotection at the regional level. As refugee crises arecross-border in nature, impacting states beyond thecountry of origin, involving a variety of actors operatingin and throughout several locations, and constitutingproblems that exist between and across multiplecountries, multilateral cooperation at the regional level isnecessary. Furthermore, if ASEAN wishes to fulfill itsstated commitments to building a “people-oriented”regional community that respects human rights and isinclusive of all people in Southeast Asia, it must urgemember states to seek alternatives to the criminalization

and detention of refugees, the most marginalizedmembers of this envisioned community.

This report aims to highlight key issues and concernsrelated to refugee protection, or lack thereof, inSoutheast Asia by outlining three refugee case studies – the Rohingya, Khmer Krom, and Lao Hmong. While notserving as an exhaustive illustration of all refugee andforcibly displaced people issues in the region, thesecases illuminate several glaring gaps in refugeeprotection in multiple ASEAN countries. The reportconsiders ASEAN’s recent responses to refugeeproblems and urges the bloc to affirm refugee rights andstrengthen protection throughout the region.Recommendations for developing a regional refugeeprotection framework are offered to ASEAN.

Methodology

To learn about the current situation of the three refugeegroups discussed in this report, People’s EmpowermentFoundation (PEF) conducted field visits and interviews

3

1 Non-refoulement is a principle of customary international law that forbids the expulsion of a refugee into an area where the person might be subjected to

persecution. It is considered binding on all states, regardless of whether or not they have ratified a relevant treaty.

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 6/22

with Rohingya, Khmer Krom, and Lao Hmong refugeesand asylum seekers in three countries. Rohingyarefugees and asylum seekers were interviewed inBangkok, Thailand and Kuala Lumpur and Penang,Malaysia. Khmer Krom refugees, asylum seekers, andother migrants were interviewed in Phnom Penh, Kandal,and Takeo provinces of Cambodia, as well as inBangkok. A discussion session with a small group of Lao Hmong refugees was held in Bangkok. In addition,

offices of the United Nations High Commissioner forRefugees (UNHCR) were consulted in Bangkok, KualaLumpur, and Phnom Penh, as were severalnongovernmental and community-based organizationsinvolved with refugee assistance and rights monitoringand protection in the three countries.

A draft of this report was presented during the“Refugees and Displaced People” workshop at the ASEAN People’s Forum (APF) in Hanoi, Vietnam on 25September 2010. The workshop was organized by PEFin cooperation with the Thai Committee for Refugees

(TCR) and the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN) and attended by civil society actors fromthroughout Southeast Asia. Recommendations for betterrefugee rights protection in the region were agreedupon by workshop participants and included in the final APF statement to ASEAN leaders. Theserecommendations, as well as content and analysis in thisreport, were finalized through consultations betweenPEF, TCR and the coordinator of APPRN for inclusion in

the report.

II. STATELESS ROHINGYA

In early 2009, Rohingya refugees received a rush of international attention when six boatloads of them werediscovered within a span of 6 weeks in the AndamanSea. Reports soon surfaced that officers of the Thai

4

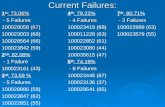

Non-protection in an international context

Southeast Asia

Source: UNHCR, October 2008

The countries in blue are

non-members to the UN

Convention Relating to

the Status of Refugees,most existing in South

and Southeast Asia.

Only two ASEAN

countries, Cambodia

and the Philippines, are

state parties to the

convention.

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 7/22

Navy had abused the Rohingya before towing them outto sea and sending them adrift without food, water, orfunctioning engines. It was found that over 1,000Rohingya had been pulled to sea before being picked upby the Indonesian Navy, with over 300 believed to havedrowned.2 From these events, the world was alerted tothe existence of a new “boat people” in Southeast Asia.

The Rohingya refugee crisis, however, has existed formany years, rooted in Burma and dispersed throughoutSoutheast Asia and beyond. A look at the currentproblems faced by exiled Rohingya in the region revealsserious human rights issues involving an array of stateand non-state actors, including but not limited to humantrafficking, prolonged detention, extortion and laborexploitation, statelessness, and an overall state of human insecurity.

Excluded and Abused in Burma

The Rohingya are a Muslim ethnic minority groupdescended from a mix of Arakanese Buddhists,Chittagonian Bengalis and Arabic sea traders.3 Incustoms, religion and language, they share severalsimilarities with neighboring Chittagonian Bengalis.4 Numbering nearly 2 million total, an estimated 800,000Rohingya live in Burma’s Arakan state, while one millionare believed to live in exile in Bangladesh, Thailand,

Malaysia, the Middle East and elsewhere.5

The conditions leading to such a dispersion outside of Burma have a legal basis in the country’s 1982Citizenship Law,6 which excludes the Rohingya from thelist of 135 officially recognized ethnic groups in Burmaand thus denies them citizenship. On this basis, theBurmese military junta regards the Rohingya as foreignresidents, rendering them stateless people with norights associated with Burma or any other nation.

As an excluded minority, the Rohingya suffer from severe

and systematic human rights violations carried out by

the ruling military regime. Such abuses, described to usby Rohingya refugees living in Thailand and Malaysia,and documented in articles and human rights reports,7 include land confiscation and forced displacement,religious intolerance, rape and sexual violence, arbitraryrestrictions on marriage, forced labor, stringentrestrictions on movement at local and national levels,arbitrary taxation on land and crop yields, and otherforms of harassment. In addition, humanitarianproblems in northern Arakan are compounded byextreme poverty and an absence of developmentinitiatives.8

Due to the severity and persistence of such persecution,masses of Rohingya have realized that staying in Burmais no longer an option. Since mass exoduses in 1978and 1991/92, hundreds of thousands have continued toflee Burma, ending up in Bangladesh, Thailand,

Malaysia, and some Middle Eastern countries, with nooption to return home safely. More recently, groupshave turned up in Cambodia and Indonesia, with sometraveling as far as Australia in hopes of acquiringasylum.

Squalor and insecurity in Bangladesh

Though not occurring in an ASEAN country, theconditions suffered by Rohingya in Bangladesh

contribute directly to the regional crisis. Adjacent tonorthern Arakan state, Bangladesh has received themost Rohingyas, with approximately 28,000 living in twoofficially recognized camps in the Cox’s Bazaar district of Southern Bangladesh (pending repatriation), another4,000 in a settlement near Kutupalong, and 9,000 in theunofficial Leda site.9 As the Bangladeshi governmentceased granting refugee status to Rohingyas in 1993,they are no longer being registered, and approximately200,000 live in the country with no officialdocumentation.

For several reasons, Bangladesh has proven unsafe for

5

2 “Indonesia’s Poor Welcome Sea Refugees,” New York Times, April 18, 2009, <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/19/world/asia/19indo.html?

scp=7&sq=rohingya&st=cse>, (accessed August 19, 2010).

3 Mathieson, David Scott, “Plight of the Damned: Burma’s Rohingya.” Global Asia, Volume 4, Number 1, Spring 2009, pg. 86-91.

4 Lewa, Chris, “Asia’s New Boat People,” Forced Migration Review, Issue 30, April 2008, pg. 40-42.

5 Refugees International, Rohingya: Burma’s Forgotten Minority , December 2008.

6 Burma Citizenship Law, October 1982, <www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3ae6b4f71b.html>, (accessed August 2, 2009).

7 See, for example, Irish Centre for Human Rights, Crimes against Humanity in Western Burma: The Situation of the Rohingyas, 2010; Lewa, Chris, “The

Rohingya: Forced Migration and Statelessness,” Forced Migration in the South Asia Region: Displacement, Human Rights and Conflict Resolution , Ed. Mishra,Omprakash, Jadavpur University Centre for Refugee Studies, 2004.

8 Equal Rights Trust, Trapped in a Cycle of Flight: Stateless Rohingya in Malaysia. January 2010, pg. 5.

9 Refugees International, Rohingya: Burma’s Forgotten Minority , December 2008.

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 8/22

Rohingya asylum seekers. Bangladesh has no legalframework for refugees, regarding them as illegaleconomic migrants rather than people in need of protection. This designation is reflected in governmentpractice. Border officials have regularly pushed back Rohingya trying to enter the country, and raids at bordercrossing points are also common. More recently,Bangladesh law enforcement agencies have escalatedtheir crackdown on unregistered Rohingya refugees,resulting in the arrest of over 500 Rohingyas within thefirst two months of 2010, some of which were jailed onillegal immigration charges and others pushed back across the Burmese border.10

Those living in unofficial camps and settlement areas aresubjected to overcrowding, food insecurity, lack of cleanwater and poor sanitation, leading to starvation,malnutrition and a variety of illnesses.11 Unofficial camp

populations are also subject to arbitrary arrest anddetention if they leave. These poor conditions, inaddition to insecure legal status and an increasinglyxenophobic local population, compel many Rohingya tomove beyond Bangladesh in search of a decent lifeelsewhere. In recent years, Bangladesh has served as atransit country for Rohingyas who depart on boatsheaded to Thailand and beyond.

“Illegal economic migrants” in Thailand

Though international attention to Rohingya refugeesarriving in Thailand peaked in 2009, as a neighboringcountry to Burma, Thailand has been a destination forRohingyas for over twenty years. In the past, overlandcrossings into Thailand were more common. SeveralRohingya we spoke with in Bangkok walked across theborder from Myawaddy to Mae Sot over ten years agoand have been living and working in Thailand’s informallabor sector ever since. More recent arrivals come byboat and stay temporarily in transit to Malaysia, thepreferred country of destination. As recent repor ts

have shown, Rohingyas arriving in Thailand findthemselves vulnerable and insecure in the context of thecountry’s strict immigration policy.

Perilousmi gra-onbysea

Before reaching Thailand, many Rohingya facehazardous conditions on boat journeys from Bangladesh(sometimes directly from Burma). Most pay traffickersto take them on crowded boats often exceeding 100people, while others pool money in large groups to

purchase a boat that they navigate themselves.Between October 2006 and March 2008, an estimated9,000 Rohingya traveled on rickety boats destined forThailand and Malaysia, with an estimated 7,500 arrivingin southern Thailand since the 2006/2007 sailingseason.12

During the voyage, boat passengers are cramped tightlyagainst each other, often unable to lie down to sleep.Rations of food and water regularly run low, resulting inhunger and starvation on the last legs of the journey.

For example, two refugees we spoke with in Penang,Malaysia reported that 13 out of 105 people on theirboat died after the engine gave out and they drifted for4 days without food before being helped by Burmesefishermen.13 The decrepit condition of many of theovercrowded boats also poses the great risk sinking inthe ocean.

Deten-on,deporta-onandpush‐back

Those fortunate enough to survive the boat journeyarrive to a country that doesn’t recognize refugees but

instead regards them as illegal economic migrantssubject to detention and deportation under the ThaiImmigration Act of 1979.14 Though Thailand has hostedtens of thousands of refugees, mostly from Burma, overthe last 30 years, the country has no refugee law and isnot party to the UN refugee convention and its protocol. With the Thai Provincial Admissions Board (PAB)assuming refugee processing operations for all migrantscoming from Burma since 2005, newly arriving Rohingyaare unable to seek asylum through the UNHCR.

In the context of illegal immigration, Rohingya who reach

the southern coast of Thailand by boat are arrestedupon arrival and put in police lockup for several daysbefore being transferred to an immigration detentioncenter (IDC), where they spend months in cramped andunsanitary quarters before being deported. SeveralRohingya reported experiences of deportation to an

6

10 The Arakan Project, Unregistered Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh: Crackdown, forced displacement, and hunger , February 2010.

11 Physicians for Human Rights, Stateless and Starving: Persecuted Rohingya Flee Burma and Starve in Bangladesh, March 2010.

12 Alternative ASEAN Network on Burma (ALTSEAN), Rohingya, Asylum Seekers and Migrants from Burma: A Human Security Priority for ASEAN , February16, 2009, pgs. 5-7.

13 Interview with two Rohingya refugees in Taman Brown commune, Gelugor district, Penang, Malaysia; July 31, 2010.

14 Thai Immigration Act, 1979, <http://www.immigration.go.th/nov2004/en/doc/Immigration_Act.pdf >, (accessed August 24, 2009).

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 9/22

area in Myawaddy, directly across the Thai border, wheretrafficking/smuggling agents wait for potential clients.Those with enough money stay in safe houses near theborder before being smuggled back into Thailand, manychoosing to go further to Malaysia.

More recently, the practice of arrest, detention anddeportation has been succeeded by a strict “push-back”policy, whereby boats carrying Rohingya refugees areexpelled to sea upon arrival to Thai shores. After the2009 revelations that the Thai Navy had sent severalboats adrift without food or working engines, thegovernment vowed to investigate incidents but stayedcommitted to their policy of barred entrance, ostensiblyto offset a perceived “pull factor.” Most recently, inMarch 2010, authorities pushed back a boat of 93Rohingya, this time with rations and a working engine.15

The current situation of a group of Rohingya capturedoff the coast of southern Thailand in late 2008 exhibitsanother troubling response to Rohingya refugeesarriving in Thailand. Before being transferred to theimmigration detention center in Bangkok, 55 of theseboat passengers were detained in Ranong, where theysuffered from respiratory problems, muscle atrophy, and

other illnesses due to improper ventilation,lack of exercise, and months of sleep on thecement floor.16 Two detainees died incustody. Once in Bangkok, a group of Bangladeshis was identified and sent back to their country, one man died, and the reststill remain, detained indefinitely with noclear policy or intended government actionin sight.

Ge;ngbyintheinformallaborsector

Rohingya who manage to enter Thailandundetected join an older generation of Rohingya refugees, many who have lived inthe country for over a decade. While theirlives are significantly better compared totheir time in Burma and Bangladesh,

Rohingya in Thailand still face certain levelsof insecurity as illegal migrants. Thoseliving in Bangkok selling roti, for example,are subject to police harassment, requiredbribes, and the constant prospect of arrest,detention, and deportation.

A Rohingya roti seller in Bangkok told us that he isrequired to pay local police 2,000 baht per month,bribing 4 departments at 500 each, to ensure that hewill be allowed to stay and earn his living.17 Severalothers told of experiences of being arrested, thrown in

the IDC, and then sent to the Mae Sot border where theywere taken to the Burma side and put in jail. They wereable to return by paying a 1,800 baht bribe, splitbetween Thai immigration and Burmese border officials.Those without money were reportedly turned over to theBurmese government, never heard from again.

Not recognized as refugees, Rohingya have had to relyon Thai migrant labor procedures to gain minimal levelsof security. For years, Rohingya and otherundocumented workers in Thailand were able to applyfor temporary work permits, renewable each year, which

allowed them to stay in the country (though they weren’ta guaranteed safeguard against deportation withoutbribe money). A new nationality verification process,however, requires proof of identity documents, such aspassports, before applying for a work permit, somethingthat Rohingya, as stateless people, are unable to obtain.

7

15 The boat subsequently arrived in Malaysia where passengers were detained before being registered by the UNHCR and eventually released to Rohingyacommunities in Kuala Lumpur and Penang with the help of the community-based Rohingya Society in Malaysia (RSM).

16 People’s Empowerment Foundation, Report: Visit to Rohingya Detainees in the Immigration Detention Center, Ranong , August 16, 2009.

17 PEF interview with Rohingya man in Bangkok, August 13, 2010.

Rohingya detained in the IDC in Bangkok / photo: Pei Palmgren

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 10/22

Criminalized and vulnerable in Malaysia

Ranked in 2009 by the US Committee for Refugees andImmigrants as one of the 10 worst places for refugeesfor the second consecutive year,18 Malaysia is “home” to90,000-170,000 refugees and asylum-seekers.19 Among them, an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 Rohingya

currently live in Malaysia, 20 with approximately 19,000registered by the UNHCR at the time of writing.

Rohingya we spoke with in Kuala Lumpur and Penangreported stories of being smuggled across the Thai-Malaysia border. The journeys usually involved a footcrossing or cramped van/truck ride in which refugeesare hidden among luggage or other cargo, a nighttimetrek through the jungle, and a van, taxi, or bus ride tothe destination city. Most Rohingya coming to Malaysiasettle in Kuala Lumpur or Penang, while communities

also exist in Johor, Kedah, and Terengganu. The mostpopular destination for Rohingya, Malaysia is arguablythe least safe place for refugees and asylum seekers inSoutheast Asia.

LegalframeworkandUNHCRo pera-ons

Like Thailand, Malaysia has yet to become a state partyto the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol and has no legal oradministrative framework for refugee protection.Rohingya and other refugees and asylum seekers are

regarded as illegal immigrants, lumped in the same legalcategory as other undocumented migrants. All aresubject to prosecution under the Immigration Act of 1959/1963 (amended in 2002),21 which rendersrefugees vulnerable to arrest, imprisonment, caning,detention and deportation.

With no government procedure in place for grantingasylum or registering refugees, such operations arehandled by the UNHCR office in Kuala Lumpur, which hasvarying capacity to protect refugees depending on levelsof government cooperation. The UNHCR now repor ts

that their relationship with the Malaysian government isthe best that it’s ever been, with increased ability tointervene when refugees are arrested and improvedaccess to detention camps and centers, where they arenow able to register refugees.

After years of issuing Rohingyas with temporaryprotection letters and then UNHCR identity cards, allsuch processes were halted at the end of 2005 after theMalaysian government announced that it would issueIMM13 temporary residence permits to the Rohingya.This scheme was soon suspended, however, due toallegations of corruption and fraud in the Rohingyacommunity-led registrations, and the government hasyet to resume such registrations.22 The UNHCRresumed their registration efforts in 2009 and iscurrently active in registering Rohingya refugees, withover 19,000 registered to date and an estimated1,000-2,000 yet to be registered.23

Targetedasillegal

Unfortunately, recognition of refugee status from theUNHCR hasn’t translated to sufficient rights protection

for Rohingya and other refugees in Malaysia. All suchmigrants are deprived of such basic rights as access tohealthcare and to schools for their children. In addition,they are unable to work legally and are thus limited tothe unsteady and exploitative informal labor sector. InFebruary 2010, Secretary General for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Datuk Mahmood Bin Adam, announcedplans to issue temporary ID cards for UNHCR-recognizedrefugees, stressing that they “cannot work here, but cando odd jobs.”24 Such cards had yet to be issued at thetime of writing.

Adding to their burdens, Rohingya refugees live inconstant fear of arrest, detention, and possibledeportation. Established in 1972 to maintain peace andsecurity in the country, the People’s Volunteer Corps(RELA) acts primarily to conduct raids and arrest of illegal immigrants. Since 2005, RELA has had expandedpowers to use firearms, raid premises and arrestrefugees and other undocumented migrants withoutwarrant. RELA often conducts joint operations withpolice and the Immigration Department, during whichlarge numbers of refugees are rounded up andarrested. In 2006 and 2007, there were several raidstargeted specifically toward Rohingya refugees.

Though RELA is said to have toned down its aggressivepursuance of Rohingyas, several we spoke withexpressed their persistent fear of immigration raids. In

8

18 United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2009.

19 Amnesty International, Abused and Abandoned: Refugees Denied Rights in Malaysia, June 2010, pg. 3.

20 Equal Rights Trust, Trapped in a Cycle o f F light: Stateless Rohingya in Malaysia. January 2010, pg. 6.

21 Malaysia Immigration Act, 1959-1963, <http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3ae6b54c0.html> (accessed August 12, 2010).

22 Equal Rights Trust, Trapped in a Cycle of Flight: Stateless Rohingya in Malaysia. January 2010, pg. 35.

23 Consultation with UNHCR officers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 26 July 2010.

24 Amnesty International, Abused and Abandoned: Refugees Denied Rights in Malaysia, June 2010, pg, 12.

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 11/22

April 2010, a young Rohingya man living in Penang hadto flee the construction site where he works when 30 to40 RELA officers arrived during lunch-hour looking forundocumented workers.25 Those with UNHCR cardswere not taken, while 19 lacking documents, includingRohingya, Indonesian, and Chinese migrant workers,were arrested and put in detention. As he hasn’t beenregistered with the UNHCR, he ran with others andmanaged to escape. He still works at the site and livesin fear of the next raid.

If arrested, Rohingya and other refugees are detained inone of 13 immigration detention centers or depots,where they live in overcrowded and grimy conditions,lacking health care, sufficient food supplies, and clean

drinking water. Fortunately, UNHCR access to suchcenters has improved dramatically since 2009, and theynow have the ability to work for release of refugees andregister asylum seekers inside the centers. Recognitionof UNHCR cards by police, immigration officials, andRELA is also said to be improving as a result of improved training efforts. There are recent reports,however, of immigration officers in detention centersdemanding bribes from refugees and asylum seekerswanting to meet UNHCR officers, limiting the improvedaccess to those able to pay for it.26

VulnerabletoHumanTrafficking

In the recent past, deportation from detention centersdirectly into the hands of human traffickers at the Thai-Malaysia border was a prevalent problem for Rohingyaand other refugees arrested in Malaysia. Collusionexisted between prison guards, immigration authorities

from both Malaysia and Thailand, and human traffickers,with deals often struck within detention centers wherebrokers were given easy access.27

The experience of a 33-year oldRohingya man living in Kuala Lumpur isconsistent with other deportationrepor ts. Though in possession of aUNHCR card, this man and his family werearrested during a nighttime raid at hishouse in July 2007. After a short stay in

an immigration depot, he was detainedfor two months in Ajil detention camp andthen deported to the Thai-Malaysiaborder, where he was sold totraffickers.28 He was then held there fordays, unable to pay for his entry back

into Malaysia and threatened to be sold toa fishing boat, until a friend sent him the

required 2,000 ringgits to be smuggled back across theborder.

Testimonies in other reports29 reveal similar experiences

of deportation and being forced to pay a trafficking feeto escape a life of bonded labor on Thai fishing boats.Many have also reported beatings throughout theprocess, by RELA officials, in detention, and bytraffickers. It is believed that “a few thousand” Burmesemigrants, including Rohingya, have been taken to theborder in this manner in recent years.30

Fortunately, this practice has reportedly been phasedout, with the UNHCR reporting that no deportations haveoccurred since July 2009. Organizations involved withrefugee victim assistance and rights monitoring also

report that they haven’t been informed of recentdeportations, though they are careful to not be overly

9

25 PEF interview with Rohingya man in Jalan Perma, Taman Brown, Gelugor, Penang, Malaysia, July 31, 2010.

26 Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Malaysia Human Rights Report 2009: Civil and Political Rights , 2010, pg. 134.

27 Equal Rights Trust, Trapped in a Cycle of Flight: Stateless Rohingya in Malaysia, January 2010, pg. 23.

28 PEF interview with Rohingya man in Taman Mudah, Cheres, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, July 16, 2010.

29 Equal Rights Trust, Trapped in a Cycle of Flight: Stateless Rohingya in Malaysia. January 2010; United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations,Trafficking and Extortion of Burmese Migrants in Malaysia and Southern Thailand , April 3, 2009; Tenaganita, The Revolving Door: Modern Day Slavery Refugees,

2008.

30 United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Trafficking and Extortion of Burmese Migrants in Malaysia and Southern Thailand , April 3, 2009.

Undocumented migrants rounded up and detained after a RELA immigration raid in

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. / photos: Mien Ly

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 12/22

optimistic about the permanence of this improvement.Possible reasons for such improvement includeincreased international attention to the problem, forexample the downgrading of Malaysia in the 2009 USTrafficking in Persons Report31 and an April 2009 reportto the United States Senate Committee on ForeignRelations, which implicated Malaysian officials in thetrafficking of Burmese refugees.32 Following suchattention, several immigration officials were arrested ontrafficking charges.

While the cycle of back-and-forth deportation andtrafficking of refugees across the Thai-Malaysia border,aided by corrupt immigration officials, appears to haveceased, trafficking from Thailand to Malaysia still existsand pervasive trafficking networks are still active in bothcountries as well as in Bangladesh and North Arakan.Many Rohingya themselves are involved in these

networks, which operate in collusion with lawenforcement officials in different locations and stages of trafficking.

More recently, in 2009 many refugees and asylumseekers from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, and Burma(including some Rohingya) began boarding boats insouthern Malaysia headed to Australia via Indonesia, inhopes of being resettled.33 Thus, while there have beensome improvements in combating trafficking of refugeesto and from Malaysia, there are still networks active inprofiting from the fears and hopes of refugees

desperate for a decent future.

III. PERSECUTED KHMER KROM

Nearly 300 Khmer Krom refugees and asylum-seekerscurrently live in Bangkok. A small number have beenrecognized as refugees by the UNHCR, with a handfulbeing granted asylum in 3rd countries. Most, however,are lying low in a country that regards them as illegalimmigrants. Though the number of recognized Khmer

Krom refugees is low compared to those of otherdisplaced groups in the region, they are a manifestationof a larger human rights crisis involving ranging forms of persecution, legal uncertainty and statelessness, andvarying levels of human insecurity in three countries of Southeast Asia.

Landlessness, poverty, and human rights abusein Vietnam

The Khmer Krom (“lower Khmer”) are a Khmer ethnicgroup from the Mekong Delta, the southernmost regionof Vietnam bordering Cambodia, the Gulf of Thailand,and the South China Sea. Most speak Khmer as theirprimary language and the vast majority practiceTheravada Buddhism, a form that is particularlymarginalized in a country already wary of religiousorganization. While the Vietnamese government has foryears pinned the Khmer population at just over onemillion, other sources estimate up to 13 million KhmerKrom people living in the country.34 The largest ethnicminority group in the Mekong Delta’s 13 provinces, theKhmer Krom are mainly concentrated in the following:Soc Trang, Tra Vinh, Kien Giang, An Giang, Bac Lieu, CanTho, Vinh Long, and Ca Mau.35

Referred to as Kampuchea Krom (“Lower Cambodia”) byits Khmer inhabitants as well as by many Cambodians

who regard the area as a lost portion of the ancestralhomeland of Khmer people, the Mekong Delta provinceswere once incorporated as part of the Frenchprotectorate, Cochinchina, before being ceded toVietnam in 1949. This colonial remapping is at the rootof the current crisis faced by Khmer Krom insideVietnam and elsewhere.

Landlessness and poverty are intertwined problemssuffered by the ethnic Khmer of the Mekong Delta, anarea with the largest number of low-income people andthe 2nd highest level of landlessness in Vietnam.36

Relying heavily on agriculture for their livelihoods, KhmerKrom people have been devastated by decades of landreform policies and practices that have effectively

10

31 The United States Department of State, T ra fficking in Persons Report, 10th Edition, June 2009; Malaysia was downgraded to “Tier 3,” indicating that the

government did not fully comply with minimum standards and weren’t making significant efforts to do so. Malaysia was upgraded to “Tier 2 Watch List” in 2010

for making significant efforts to comply with standards.

32 United States Senate Committee on For eign Relations, Trafficking and Extortion of Burmese Migrants in Malaysia and Southern Thailand , April 3, 2009.

33 Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Malaysia Human Rights Report 2009: Civil and Political Rights , 2010, pg. 135.

34 “Religion, politics and race,” Phnom Penh Post , May 4-17, 2007.

35 Human Rights Watch, On the Margins: Rights Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, January 2009, pg. 14.

36 AusAID, Mekong Delta Poverty Analysis, 2004, pg. 21.

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 13/22

redistributed the majority of formerly Khmer Krom-owned land to the Vietnamese government and ethnicVietnamese farmers.37 Land-grabs by corruptgovernment officials persisted in subsequent years,leading to land rights protests that grew in the 1990s. An escalation of such protests occurred in 2007 and2008 with increasinglysevere repression.38 Fearing harsh reprisalfrom the Vietnamesegovernment, many knownleaders of such protestshave fled the country.

Despite guarantees of freedom of belief andreligion in the Vietnameseconstitution,39 persistent

threats to religious andcultural freedoms of theKhmer Krom are common.Vietnamese authoritiesstrictly control localpractices among KhmerBuddhists, makingintrusive decisions about religious ceremonies, contentof curriculum, internal elections of chief monks, andmore recently, disciplinary measures. The confiscation,destruction, and neglect of Khmer Krom pagodas hasalso angered religious rights activists, as thesestructures serve as centers for the preservation of Khmer religion, culture and identity. Practice of Khmerlanguage is under threat as well, with some policereportedly prohibiting Khmer instruction in Pagodaschools, the only sources of such education.

Though article 69 of the Vietnamese constitutionespouses a commendable list of civil liberties, practicesin relation to the Khmer Krom (among other ethnicminorities and religious groups) consistently run counterto such obligations as well as to those outlined in the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights(ICCPR), to which Vietnam is a state party. Freedom of movement is restricted at local and national levels,

particularly for monks, and leaving the country withoutprior authorization is prohibited. Freedoms of expression and assembly are also regularly abused, asevidenced in restrictions on Khmer languagepublications and harsh repression of peacefuldemonstrations.

Violations of civil andpolitical rights were mademost clear during thepolice crackdown onpeaceful monk protestsand land rightsdemonstrations thatoccurred in 2007 and2008, deemed by HumanRights Watch as “bare-knuckled, indefensible

political repression.”40

The monk demonstrations,calling for more religiousfreedom and Khmerlanguage/cultureeducation, resulted in thearrest and eventual

defrocking (disrobing) of several activist monks, despitepledges by authorities to address the monks’concerns.41

Around the same time, growing numbers of protests by

poor and landless farmers were met with harshrepression tactics, including the use of dogs and electricbatons to disperse crowds.42 As with the monk protests, arrest and increasingly stringent surveillanceof activist leaders followed, leading to prevalent fears of government reprisal. These fears have prompted manyknown activists to flee the country, with severaleventually ending up in Thailand as asylum seekers.

Statelessness and insecurity in Cambodia

Fleeing desperate poverty, landlessness, and an overallenvironment of discrimination against ethnic Khmers in

11

37 Khmer Krom Federation, The Khmer Krom Journey to Self-Determination, 2009, pg. 167.

38 On the Margins: Rights Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, Human Rights Watch, January 2009, pg. 47

39 1992 Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (As Amended 25 December 2001), Article 70.

40 “Vietnam: Halt Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Mekong Delta,” Human Rights Watch statement, January 2009.

41 Human Rights Watch, On the Margins: Rights Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, January 2009, pgs. 27-43.

42 Ibid. 44-48.

Five defrocked Khmer Krom monks, eventually given asylum and

resettled in the Netherlands and Sweden. / photo: Lenny Thach

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 14/22

Vietnam, since the early 1980s hundreds of thousandsof Khmer Krom (the majority not asylum seekers) havemade the surreptitious journey out of their villages andthrough unofficial border crossings – usually on footwith the help of locals living along the border – insearch of better lives in neighboring Cambodia, acountry with language and religion common to theKhmers from Vietnam. Religious and land rights activistshave migrated more recently to seek protection fromVietnamese government reprisal. Gaining suchprotection from the Cambodian government, however,has proven complicated and disheartening for many.

Unfulfilledci-zenshippromisesanddeniedasylum

The Cambodian Law on Nationality, adopted in 1996,states that any person who has one or both parents of Khmer nationality is afforded rights as a Cambodian

citizen,43

offering a vague definition of citizenship that isopen to interpretation by government officialsresponsible for implementation. The Cambodiangovernment has, however, made repeated statementsaffirming full citizenship and corresponding stateprotection for Khmer Krom people from Vietnam.44

Unfortunately, government practices have provencontradictory to their statements, instead taking theform of discriminatory, inconsistent, and ambiguousprocesses of citizenship recognition at commune anddistrict levels that have rendered many Khmer Krom

stateless.45 Khmer Krom residents we spoke withreported discrimination by local officials administeringregistration campaigns, including intentional neglect of Khmer Krom households during notifications, def erralsof Khmer Krom registration to future registration phasesthat never occur, and outright denial of registrationopportunities based on Khmer Krom identity. Corruptionamong local officials in the form of demanded bribes forservices promised by the government was alsorepor ted. Such actions have effectively restricted thepoorest Khmer Krom individuals and families from thecitizenship registration process.

More recently, Khmer Krom individuals and communitieswho have lived in the country for years have been ableto obtain identification cards only under the condition

that they change their birthplace to a Cambodianlocation and their surnames to those that don’t revealKhmer Krom identity. Every individual we interviewedwho was able to obtain an identification card did sothrough this process of denied identity. In one case, anentire village of 104 people was denied ID cards untilmaking these changes.46 Though this recent trendsuggests that more people are gaining citizenship andavoiding statelessness, it is nevertheless problematic

that Khmer Krom are forced to renounce their identityand falsify information to obtain proof of citizenship.

Rather than helping those fleeing persecution inVietnam, the government’s citizenship promise has onlycomplicated the process of asylum seeking for KhmerKrom in Cambodia. Though Cambodia is party to the1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugeesand its 1967 Protocol, the government’s insistence thatethnic Khmers from Vietnam are automatic Cambodiancitizens precludes their refugee status in Cambodia.Prior to 2005, Khmer Krom were able to seek asylum inCambodia and several successfully gained refugeestatus with the UNHCR in Phnom Penh. The asylumapplication process ended, however, after the

Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent a letter to theUNHCR assuring them that the Khmer Krom have fullcitizenship status in the country.47

12

43 Cambodia Law on Nationality, article 4, <http://www.interior.gov.kh/uploads/files/Law_on_Nationality.pdf > (accessed August 10, 2010).

44 Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs letter No. 1419, August 2, 2005; Letter from the deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs to the Minister

of justice, letter No. 7725, November 21, 2006; “His Excellency Deputy Prime Minister Hor Namhong meets with the US Assistant Secretary of State,” Permanent

Mission of the Kingdom of Cambodia to the United Nations Monthly Bulletin, March 2007, <http://www.un.int/cam bodia/Bulletin_Files/March07/

Minister_HOR_Namhong_meets_with_US.pdf > (accessed August 10, 2010).

45 See Khmer Kampuchea Krom Human Rights Organization, Report: Problem Assessment/survey and 2007 Project Monitoring, Koh Kong and Sihanoukville,

May 11, 2007; Khmer Kampuchea Krom Human Rights Organization, Report: On Collecting the Issues and Statistics of Khmer Kampuchea Krom in theCommunities of Ka-Orm Samnor Commune, Leuk Dek District, Kandal Province, July 30, 2007.

46 PEF interview with Khmer Krom community leader of Khsom Village, Baneay Dec Commune, Kien Svay District, Kandal Province, Cambodia, July 10, 2010.

47 Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs letter No. 1419, August 2, 2005.

Stateless Khmer Krom children, Kandal province, Cambodia. /

photo: Pei Palm ren

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 15/22

Since the 2005 citizenship affirmation, the UNHCR hasnot allowed any asylum applications to be submitted byKhmer Krom who have fled Vietnam, maintaining that, asa refugee agency, they are unable to offer protectionand/or assistance to people within their country of citizenship. The government-run refugee agency, whichhas recently assumed control of refugee statusdetermination in the country, will undoubtedly continueto deny any asylum bids from those that they assert areCambodian citizens.

Without the prospect of gaining refugee status, someasylum seekers have attempted to gain the citizenshipthat is promised to them, which proves to be afrustrating and often futile process. For example, agroup of 24 Khmer Krom asylum seekers who weredeported from Thailand to Poipet, Cambodia, inDecember 2009 spent months, with the help of local

NGOs and the UN Office of the High Commissioner forHuman rights (OHCHR), trying to gain identificationcards to live legally in Cambodia. With their legal statusin limbo, they were eventually denied identification cardson the basis of having no fixed address, yet they wereunable to find jobs and rent homes without first havingthe cards.48

Those unable to obtain citizenship documents are livingas stateless people without full rights afforded tocitizens. As such, they face several social and economicdisadvantages, including lack of access to healthcare,

restricted employment opportunities, inability to vote,denial of bir th certificates and education for children,limits to free travel, and restrictions on owning land.49 The lack of a regularized citizenship registrationprocess for the Khmer Krom in Cambodia is contributinga crisis of statelessness that affects both asylumseekers and other Khmer Krom migrant communities.Such conditions of statelessness are in turn potentialcauses of refugee situations that could grow if leftunaddressed.

RepressionandinsecurityofKhmerKromac-vists

Throughout 2007, several incidents occurred thathighlighted the lack of rights and security enjoyed bypolitically active Khmer Krom monks in Cambodia, manyof whom fled government reprisal after protestcrackdowns in Vietnam. On February 27, fifty-two such

monks holding a peaceful demonstration in support of fellow monks in Vietnam were stopped by over 150Cambodian police wielding shields, tear gas, electricbatons and guns outside of the Vietnamese embassy inPhnom Penh.50 The monks were held in buses andthreatened with defrocking before being released afterintervention from local human rights workers.51 Laterthat night, one of the monks, Eang Sok Thoen, wasfound dead in his pagoda with his throat slit in threeplaces. Within 24 hours the death was labeled a suicideand the body was buried before an autopsy or any

investigation could be conducted.52

Rights workersbelieve that the death was a murder likely related to thedemonstrations.

Subsequent incidents occurred throughout 2007, duringwhich monks attempting to deliver letters to theVietnamese embassy in Phnom Penh protesting thedefrocking, imprisonment, and disappearance of monksin Vietnam were confronted by heavily armed police andin one case a group of unidentified civilians and localmonks. Such incidents resulted in clashes, a nighttimebeating of a Khmer Krom monk on his way home, and

the use of electric batons by police who chased andbeat monks as they fled the heavily shielded embassy. 53

Seemingly in response to the earlier demonstrations, onJune 8, Supreme Patriarch, Non Nget, chief of PhnomPenh monks, issued a directive in conjunction with theMinister of Cults and Religion, Khun Haing, orderingmonks in the country to stop taking part in suchprotests. In addition, monks known to have participatedin the 2007 demonstrations reported being under closesurveillance by Cambodian authorities, with one telling

13

48 “Khmer Krom ID denied,” The Phnom Penh Post , February 22, 2010.

49 Khmer Kampuchea Krom Human Rights Organization, 2008 Annual Narrative Report , December 2008; PEF interviews with Khmer Krom people in Takeo and

Kandal provinces, Cambodia, July 10-12, 2010.

50 “50 Monks Stage Protest Near Vietnamese Embassy,” The Cambodia Daily, February 28, 2007.

51 LICADHO, Attacks & Threats Against Human Rights Defenders in Cambodia, 2007 , August 2008.52 Ibid.

53 LICADHO, Attacks & Threats Against Human Rights Defenders in Cambodia, 2007 , August 2008; “Khmer Kampuchea Krom Monks Chased and Assaulted by

Police in Phnom Penh,” CCHR-CHRAC-CLEC-LICADHO Media Statement, December 17, 2007.

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 16/22

us that he was compelled to go into temporary hidingdue to continual harassment and threats of arrest. 54 Furthermore, it is widely believed among monks andhuman rights workers that Vietnamese spies, recognizedas regular visitors to pagodas, are also involved inmonitoring Khmer Krom monk activities within Cambodia.

The above incidents and surveillance measures clearlyindicate a concerted effort on the part of Cambodianauthorities to curb any political activity, howeverpeaceful, of Khmer Krom monks. Such efforts seem tobe working, as no further demonstrations have occurredsince the end of 2007. Several monks we interviewedexpressed their fear of being politically active and theirlack of confidence in the Cambodian government toprotect them, especially after the death of Eang Sok Thoen and the arrest, deportation, and sentencing inVietnam of Tim Sakhorn,55 a leading activist monk who

had previously been defrocked for allegedly breachingBuddhist discipline and causing a “split in national andinternational unity, especially between the two countriesof Cambodia and Vietnam.”56

The Tim Sakhorn case is especially alarming, as ithighlights the cross-border collaboration that is takingplace between Cambodia and Vietnamese governmentsin suppressing Khmer Krom activism, revealed in various

internal Vietnamese government reports and memos.57 Recently, Vietnam’s deputy minister of public security,Tran Dai Quang, lauded Cambodian authorities for

helping to combat what he called “plots and operationsof hostile forces opposing the Vietnamese revolution,”also accusing Khmer Krom activists of trying to “opposeand destroy.”58 Such cross-border collaboration hasalso been reported in cases involving non-monks, suchas the attempted arrest of a man in Cambodia byVietnamese police for distributing Khmer Krom-relatedbooks.59

Considering the strict repression of Khmer Krom politicalactivity in Cambodia and the ability Vietnameseauthorities have in monitoring and arresting dissidentsin the country, it is understandable that those whofeared reprisal inside Vietnam are also afraid for theirsecurity in Cambodia. Such a fear has compelled anincreasing number of Khmer Krom rights activists toseek asylum in Thailand.

Searching for refuge in Thailand

Many Khmer Krom activists on the blacklist of theVietnamese government have escaped to Thailand dueto insecurity in Cambodia, crossing the border covertlyby foot with the help of locals. There are currentlynearly 300 Khmer Krom refugees living in Bangkok,regarded as illegal immigrants by the Thai government.

Already rejected or withdiminishing prospects of

asylum, many live in poor andinsecure conditions, distressedby constant fear of arrest anddeportation.

SeekingasyluminBangkok

In early 2007, the UNHCR inBangkok provided severalKhmer Krom asylum seekerswith certificates that minimizedthe threat of deportation, and

a few were granted refugeestatus. As the situation inVietnam and Cambodia

deteriorated in late 2008, increasing numbers beganarriving, and over 40 Khmer Krom have now been

14

54 PEF interview with 28-year-old Khmer Krom monk in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, July 13 2010.

55 See Human Rights Watch, On the Margins: Rights Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, January 2009, pg. 68; After his initial disappearance,

Sakhorn was sentenced to a year in prison by a court in An Giang province for violating Vietnam’s national unity policy under article 87 of the country’s penal

code. He was subsequently released and allowed to return to Cambodia. He eventually fled to Thailand and gained asylum in Sweden, where he now lives.

56 “Tep Vong Orders Khmer Krom Monk Defrocked,” The Cambodia Daily, July 2, 2007.

57 Human Rights Watch, On the Margins: Rights Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, January 2009, pg. 75.

58 “Vietnam applauds Cambodia’s help in combating ‘plots,’ Deutsche P resse Agentur , August 4, 2010.

59 “Khmer Krom man on the run from Vietnamese arrest (inside Cambodia!),” Radio Free Asia, February 22, 2009.

Left: Khmer Krom kids in Bangkok, unable to attend school; Right: preparing ingredients for

local food vendors / photos: Ang Chanrith

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 17/22

recognized as refugees, while over 100 have beenrejected.60 In addition, 6 monks who fled to Bangkok after their arrest and subsequent release in Vietnamwere eventually granted asylum and resettlement.

Many Khmer Krom, however, have been denied asylumdue to lack of or insufficient documentation proving

serious threats of individual persecution by theVietnamese government, such as written arrest warrantsor records of imprisonment, which are difficult to obtaingiven the arbitrary nature of their arrests. Others havehad difficulty with applications because of misconceptions of citizenship recognition in Cambodia. With the UNHCR understanding that all Khmer Krom aregranted Cambodian citizenship, asylum applicants mustsubstantiate persecution in both countries to berecognized as refugees in Thailand. This complicatesthe asylum application process, as complex

circumstances of citizenship denial and insecurity inCambodia may not yet be fully understood.

Lingeringrisksofdeporta-on

Several of the Khmer Krom we spoke with in Thailandhave asylum seeker certificates that have expired or willsoon expire. Without the prospect of gaining refugeestatus, and afraid for their security in both Vietnam andCambodia, these former activists have little choice but tolive as illegal immigrants, marginalized and insecure. Assuch, they lead inconspicuous lives, avoiding activity

during the day and limiting their travel out of fear of being arrested and deported.

Such fear has been substantiated by the Thaigovernment’s strict deportation policy and recent recordof Khmer Krom deportations. On June 13, 2009, forexample, 62 Khmer Krom were arrested and 54 wereeventually deported to Cambodia. Some of thedeportees, many of whom fled Vietnam because of landdisputes with the government, had certificates from theUNHCR recognizing their asylum applications.

In December 2009, 24 Khmer Krom were deported toCambodia, some of whom had re-entered Thailand afterbeing deported in June. Again, several of them were invarious stages of the asylum application process. Afterfailing to obtain the documents necessary for theissuance of Cambodian ID cards, many of these KhmerKrom asylum seekers have returned to Thailand asstateless migrants.

Povertyandmarginaliza-on

Deprived of legitimate legal status, Khmer Krom asylum

seekers rely on informal jobs to support themselves. A

group we talked to reported earning an average of 100baht per day doing informal tasks for Thais at the localmarket, such as food preparation and cleaning. Ahandful of men have found temporary work onconstruction sites. Fearing arrest, many stay at homeduring the day and go out looking for work at night,which limits the opportunities available. Their status asillegal immigrants has also left many vulnerable to laborexploitation by employers who can easily withholdpayment from “illegal” migrants too afraid to turn toauthorities. A handful of Khmer Krom have been able toregister, with the help of local NGOs, as temporarymigrant workers, which offers them some levels of security.

Given the lack of stable employment opportunities,those residing in and around Bangkok live as some of the poorest and most marginalized people in Thai

society. Many have problems earning enough money toprovide adequate supplies of food for their families andat times resort to begging from local Buddhist temples.Securing decent housing is also a challenge. KhmerKrom and other refugees are restricted to the poorestareas of Bangkok that have relatively affordable rent. Without legal status, they must rely on supportive Thaipeople to help them rent houses, providing the Thaifriends money to pay rent in their names.

Lack of access to education for children and healthcareare also of great concern to those we spoke with. Many

requested access to public schooling but were rejectedbecause the government doesn’t accept children of non-citizens who were not born in the country. None of thechildren who live in the community we visited wereattending school, a heartbreaking reality for the parents,who become very emotional when talking about theuncertain future of their children. As non-citizens, theKhmer Krom have no access to healthcare and cannotgo to hospitals for proper treatment of illnesses, insteadlimited to insufficient remedies from the pharmacy. Withlittle hope of gaining asylum, these conditions are the

norm for Khmer Krom in Thailand who are becomingincreasingly dejected about their limited prospects forthe future.

IV. LAO HMONG ON THE RUN

In late December 2009, the Thai government forciblyreturned nearly 4,500 Lao Hmong who had been living

in a makeshift camp in Petchabun province back to Laos.

15

60 Discussion with UNHCR Senior Protection Officer in Bangkok

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 18/22

Another 158 Lao Hmong who had been detained in aNong Khai detention center for three years were alsodeported, despite the fact that they had beenrecognized as refugees and accepted for resettlementto 3rd countries. Though the Lao government hasassured Thailand and the international community thatthe returnees will be resettled without harm, manyHmong fear for their safety in Laos. Such an act of refoulement , as well as the conditions suffered by therefugees while in Thailand, constitutes one of the moretroubling responses to a refugee crisis in the region.

Hiding in the jungles of Laos

The Hmong are a highland tribe residing in southernChina, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand. Theybegan settling as farmers in the northern mountains of Laos in the late eighteenth century and currentlynumber 450,000, constituting 8% of the totalpopulation and the third largest ethnic group in thecountry.61

Beginning in the early 1960s, many ethnic Hmongfought against the Communist Pathel Lao forces as partof the CIA-funded “Secret Army,” formed primarily toattack communist supply routes running through the jungles of Laos. After the communist victory in Laos in1975, the new government sent many Hmong and other

opponents to “re-education” camps, where they wereheld without trial in harsh conditions for over adecade.62 An estimated 10,000 Hmong were killed inretribution during this time.63 Others fled Laos, mostlyto seek refugee status in Thailand and resettleelsewhere. Between 1975 and 1996, over 125,000Hmong refugees were resettled in third countries, mostgoing to the United States.64

Thousands of Hmong who stayed in Laos retreated toforest areas out of fear of retribution from the new Laogovernment, forming an armed resistance movement

that was quickly thwar ted and is nonexistent today, withthe exception of a few armed “bandits.”65 Currently, afew thousand Hmong, including women, children andelderly, still live in hiding in jungles areas of Bolikhamxay,Xieng Khouang, Vietiane, and Luang Phrabang

provinces.66 In addition to lacking adequate food,clothing, housing, and medical care, these scatteredgroups are subject to attacks and persecution by theLao military, which continually ambushes clusters of nomadic Hmong.

The few journalists who have accessed the jungle

encampments have reported on desperate groups of poor and malnourished families living in makeshiftbamboo shacks, many having bullet and shrapnelwounds suffered while foraging for food.67 Hmongrefugees we talked to in Thailand also described asevere lack of food and clothing during their time in the jungle and reported constantly having to relocate out of fear of being killed by soldiers. Those who havesurrendered have reportedly been harassed, detainedand subjected to various forms of ill treatment by thegovernment.68 As such, fleeing to Thailand is thought to

be the only hope for many in need of safety.

Warehoused in Thailand

For years, Thailand was the main hosting country forHmong who fled Laos. In late 2004, many Hmong fromthe jungles began crossing the Mekong River intoThailand, with large numbers settling in Petchabunprovince. Others made their way to Bangkok and otherprovinces, where they lived furtively as undocumented

immigrants. Though Thailand used to be known forhelping to resettle the Hmong, more recently thegovernment has implemented detention and deportationpolicies that have endangered many Hmong fearingpersecution in Laos.

ConfinedinHuaiNamKhaocamp

After first living in forests on the outskirts of Huai NamKhao village, subsisting on food provided by localresidents and working on local farms, five to sixthousand Hmong asylum seekers were eventually forced

to settle on the sides of the town’s main road incramped living spaces with little access to food, shelter,drinking water and healthcare (Medicins Sans Frontieressoon set up an outpatient clinic). By mid-2007, therewhere 7,500 Hmong living in the encampment, and soon

16

61 Amnesty International, Hiding in the Jungle: Hmong Under Threat , March 2007, pg. 4.

62 Ibid. 5

63 “The Hmong and the CIA,” Time, December 20, 2009.

64 Amnesty International, Hiding in the Jungle: Hmong Under Threat , March 2007, pg. 5.

65 Ibid. 5.

66 Ibid. 9.67 “Out of the Jungle,” Al Jazeera, March 13, 2008. < http://english.aljazeera.net/news/asia-pacific/2008/03/2008525185848806332.html> (accessed September 1,

2010).

68 Amnesty International, Hiding in the Jungle: Hmong Under Threat , March 1007, pg. 16.

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 19/22

after they were relocated to a barbed-wire-enclosedcamp three kilometers from the village center.

The Huai Nam Khao camp was strictly controlled by theThai military, which restricted movements of Hmong toinside the camps. No educational facilities for childrenor employment opportunities for adults existed. In

addition, the UNHCR wasprevented from accessingthe Hmong to carry outrefugee statusdeterminations. The Thaigovernment, maintainingthat the Hmong wereillegal economic migrants,refused to recognize themas asylum seekers andcarried out no refugee

processing of their own.

Inside the camp, MedicinsSans Frontieres (MSF)provided humanitarian aidto the Hmong until April2009, when the Thai-based Catholic Office forEmergency Relief and Refugees (COERR) was chosen bythe military to take over such operations. During theirtime working in the camp, MSF found that the mainhealth problems suffered by the Hmong were

psychological, mainly anxiety exacerbated by theconstant fear of repatriation.69

DetainedasillegalimmigrantsinNongKhai

Outside of the camp, hundreds of Hmong settled inBangkok and other provinces, living in hiding andsometimes moving so as to avoid being noticed by localpolice. Despite obtaining UNHCR certificates evidencingrefugee status, they still feared deportation in a countrythat fails to recognize Hmong as refugees. In 2006,194 of these Hmong (most from Laos but a few from

Vietnam) were arrested during a 6 am police raid ontheir homes. They were sent to the IDC in Bangkok for21 days before being transferred to the Nong Khaidetention center, where they lived in jail-like conditionsfor three years. The handful of Hmong from Vietnamwas immediately sent to that country.

In the Nong Khai detention center, the refugees slept onthe floor in two cells separated by gender. They weregiven 2 hours of exercise per day and had a limited

amount of food and access to clean water and propersanitation facilities.70 In 2007, all 158 (some born indetention) Hmong refugees obtained visas to beresettled to 3rd countries after being interviewed by theUNHCR and embassies of the United States, Australia,the Netherlands, and Canada. Such resettlement,however, was denied by the Thai government, which

instead deported theHmong in Nong Khai, aswell as those in the HuaiNam Kao camp, to Laos.

Vic-msofRefoulement

In May 2007, Thailand andLaos signed the Lao-ThaiCommittee on BorderSecurity agreement, which

allowed Thailand to sendany Hmong asylum-seekers back upon arrivalin Thailand. In September2007, the two countriesagreed that the Hmong inHuai Nam Khao would berepatriated before the end

of 2008. Though this mass repatriation was halted byinterventions from the UNHCR and several local andinternational human rights organizations, over onehundred Hmong, including several children, were forcibly

returned to Laos throughout 2007.71 Though the Laogovernment denied mistreatment of these returnees,they never allowed independent monitors to investigatereports that emerged of forced disappearances,torture, and arbitrary detention upon return.72

On the morning of December 28, 2009, representativesfrom 3rd country embassies came to the Nong Khaidetention center to inform the Hmong that they would besent back to Laos for 30 days before being resettled inthe countries that accepted them. Later that evening,the phone signal in the center was cut off and hundredsof soldiers came to put the Hmong on a bus headedacross the border to Laos. The worst fears of those inthe Huai Nam Khao camp also came true on December29, when police wielding shields and dressed in riot gearevicted the Hmong and sent them on their way to Laos.

17

69 Medecins Sans Frontieres, Briefing Paper: The Situation of the Lao Hmong Refuges in Petchabun, Thailand, October 2007.

70 PEF discussion with Hmong refugees in Bangkok, August 23, 2010.

71 Medecins Sans Frontieres, Briefing Paper: The Situation of the Lao Hmong Refuges in Petchabun, Thailand , October 2007.

72 “URGENT ACTION: Refugees Forcibly Returned to Laos,” Amnesty International , January 13, 2010.

Lao Hmong kids in Huai Nam Khao camp, Petchabun province,

Thailand. / photo: Ann Peters

8/4/2019 Report: "Refugee Protection in ASEAN: National Failures, Regional Responsibilities"

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/report-refugee-protection-in-asean-national-failures-regional-responsibilities 20/22

Forced repatriation

Though told they would be taken to hotels in Vientiane,the deported Hmong from the Nong Khai detentioncenter were instead taken to an army camp and then toa larger camp in Bolican Sai province, where manyHmong from the Huai Nam Khao camp were also taken.

At this camp, they were strictly guarded by soldiers andhad to be asleep by 8 pm each night. The governmentprovided only small rations of rice and instant noodlesfor food.

Those from Nong Khai reported being monitored muchmore closely than those from the camp in Petchabun. Inaddition, they were coerced into writing letters statingthat the Lao government was taking good care of themand that they wanted to stay in Laos. Those whosubsequently escaped and returned to Thailand

reported to us that they were threatened and beatenbefore they agreed to sign the letters.

After a week in the Bolican Sai camp, the Hmongreturnees were moved to the Phonkham resettlementvillage in Borikhamxay province, where they live today(with the exception of escapees and the few who haverepor tedly been resettled in other villages). In thisvillage, police strictly controlled the returnees’movements and watched over them 24 hours a day. After clusters of returnees began escaping the camp,guards reportedly threatened to kill those who

attempted to do the same. The government has alsokept them in the dark about their situations, especiallyregarding the promised resettlement to 3rd countries.