Report on Internal Control and on Compliance and … ON INTERNAL CONTROL AND ON COMPLIANCE AND OTHER...

-

Upload

nguyenkhuong -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

1

Transcript of Report on Internal Control and on Compliance and … ON INTERNAL CONTROL AND ON COMPLIANCE AND OTHER...

REPORT ON INTERNAL CONTROL AND ON COMPLIANCE AND OTHER MATTERS

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF PHILADELPHIA

FISCAL 2012

June 5, 2013 Pedro A. Ramos, Esq., Chairman and Members of the School Reform Commission 440 N. Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19130 Dear Chairman Ramos and Members: In accordance with the Philadelphia Home Rule Charter, the Office of the City Controller conducted an audit of the basic financial statements of the School District of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as of and for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2012, and has issued its Independent Auditor’s Report dated February 11, 2013. In planning and performing our audit, we considered the School District of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s internal control over financial reporting as a basis for designing our auditing procedures for the purpose of expressing our opinions on the financial statements, but not for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the School District of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s internal control over financial reporting. Accordingly, we do not express an opinion on the effectiveness of the District’s internal control over financial reporting. Attached is our report on internal control over financial reporting and on compliance and other matters, dated February 11, 2013 and signed by my deputy who is a Certified Public Accountant. The findings and recommendations contained in the report were discussed with management at an exit conference. We included management’s written response to the findings and recommendations and our comments on that response as part of the report. We believe that, if implemented by management, these recommendations will improve the School District of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s internal control over financial reporting. We would like to express our thanks to the management and staff of the School District of Philadelphia for their courtesy and cooperation in the conduct of our audit. Respectfully submitted, ALAN BUTKOVITZ City Controller cc: William R. Hite, Jr., Ed.D., Chief Executive Officer and Superintendent of Schools Matthew E. Stanski, Chief Financial Officer Marcy F. Blender, CPA, Deputy CFO and Comptroller

REPORT ON INTERNAL CONTROL OVER FINANCIAL REPORTING AND ON COMPLIANCE AND OTHER MATTERS BASED ON AN AUDIT OF FINANCIAL STATEMENTS PERFORMED IN ACCORDANCE WITH

GOVERNMENT AUDITING STANDARDS To the Chair and Members of The School Reform Commission of the School District of Philadelphia We have audited the financial statements of the governmental activities, the business-type activities, each major fund, and the aggregate remaining fund information of the School District of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (School District), a component unit of the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as of and for the year ended June 30, 2012, which collectively comprise the School District's basic financial statements and have issued our report thereon dated February 11, 2013. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America and the standards applicable to financial audits contained in Government Auditing Standards, issued by the Comptroller General of the United States. Internal Control Over Financial Reporting Management of the School District is responsible for establishing and maintaining effective internal control over financial reporting. In planning and performing our audit, we considered the School District’s internal control over financial reporting as a basis for designing our auditing procedures for the purpose of expressing our opinions on the financial statements, but not for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the School District’s internal control over financial reporting. Accordingly, we do not express an opinion on the effectiveness of the School District’s internal control over financial reporting. Our consideration of internal control over financial reporting was for the limited purpose described in the preceding paragraph and was not designed to identify all deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting that might be significant deficiencies or material weaknesses and therefore, there can be no assurance that all deficiencies, significant deficiencies, or material weaknesses have been identified. However, as described in the accompanying report, we identified a certain deficiency in internal control over financial reporting that we consider to be a material weakness and another deficiency that we consider to be a significant deficiency.

C I T Y O F P H I L A D E L P H I A O F F I C E O F T H E C O N T R O L L E R

A deficiency in internal control exists when the design or operation of a control does not allow management or employees, in the normal course of performing their assigned functions, to prevent, or detect and correct misstatements on a timely basis. A material weakness is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements will not be prevented, or detected and corrected on a timely basis. We consider the following deficiency described in the accompanying report to be a material weakness:

• Ineffective procedures for reconciling reported equity in pooled cash and investment amounts to the balance of cash and investments in the bank resulted in the failure to timely detect material financial statement errors.

A significant deficiency is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control that is less severe than a material weakness, yet important enough to merit attention by those charged with governance. We consider the following deficiency described in the accompanying report to be a significant deficiency:

• Inadequate design and operation of controls over the furniture and equipment inventory increased the risk of asset misappropriation.

Compliance and Other Matters As part of obtaining reasonable assurance about whether the School District’s financial statements are free of material misstatement, we performed tests of its compliance with certain provisions of laws, regulations, contracts, and grant agreements, noncompliance with which could have a direct and material effect on the determination of financial statement amounts. However, providing an opinion on compliance with those provisions was not an objective of our audit, and accordingly, we do not express such an opinion. The results of our tests disclosed no instances of noncompliance or other matters that are required to be reported under Government Auditing Standards. We noted certain other conditions that represent deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting and compliance that are listed in the table of contents and described in the accompanying report. We also identified other internal control deficiencies during an assessment of information technology general controls conducted by an independent accounting firm engaged by us, which will be communicated to School District management in a separate report. Additionally, we noted a compliance condition that will be communicated to School District management in separate correspondence. The School District’s written response to the material weakness, significant deficiency, and other conditions identified in our audit is included as part of the accompanying report. We did not audit the School District’s response and, accordingly, we express no opinion on it. We have also included our comments to the School District’s responses that we believe do not adequately address our findings and recommendations.

C I T Y O F P H I L A D E L P H I A O F F I C E O F T H E C O N T R O L L E R

This report is intended solely for the information and use of the management of the School District, the School Reform Commission, and others within the entity, and is not intended to be and should not be used by anyone other than these specified parties. February 11, 2013 GERALD V. MICCIULLA, CPA Deputy City Controller

CONTENTS

Page MATERIAL WEAKNESS Cash Reconciliation Procedures Needed Improvement ........................................................... 1 SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY Safeguarding and Recordkeeping over School Furniture and Equipment Were Inadequate ......................................................................................................................... 3 OTHER CONDITIONS

Management of Petty Cash Remained Deficient ..................................................................... 13 Oversight of Student Activity Funds Remained Problematic ................................................. 15 Controls over Student TransPass Activity Continued to Need Enhancing ............................. 19 Financial Statement Review Procedures Needed Management’s Attention .......................... 21 Eligible Costs Were Not Always Capitalized .......................................................................... 22

Artwork Records Not Yet Adequately Updated ...................................................................... 23 Monitoring of Unapproved Payrolls Continued to Need Strengthening ................................ 25 Tax Treatment for Termination Payments Has Still Not Received State and City Confirmation ...................................................................................................................... 27

Long Outstanding Termination Pay Should Be Escheated ..................................................... 28 Review Procedure for Processing Termination Compensation Not Adequately Documented ........................................................................................................... 30 Integrity of Payroll Passwords Continued to Be Compromised .............................................. 30 Non-Compliance with Statement of Financial Interest Filing Requirements ......................... 31 Minutes of Public Meetings Not Published .............................................................................. 32 Procedures for School Security Cameras Still Required Formal Approval ............................ 32

CORRECTIVE ACTIONS TAKEN BY DISTRICT

Student Dental Care Benefits No Longer Paid Through the Public School Health Fund ................................................................................................................................ 34 Encumbrance Policy Now Clarified ......................................................................................... 34 CAFR Preparation Procedures Now Improved ........................................................................ 35 Completed Project Costs Now Properly Transferred Out of Construction in Progress ................................................................................................................................. 35

APPENDIX I: OBSERVATIONS AT FORMER WEST PHILADELPHIA HIGH SCHOOL .........................................................................................................................37

RESPONSE TO AUDITOR’S REPORT

Matthew E. Stanski, Chief Financial Officer ........................................................................... 38

AUDITOR’S COMMENTS ON AGENCY’S RESPONSE ....................................................... 53

MATERIAL WEAKNESS

1

CASH RECONCILIATION PROCEDURES NEEDED IMPROVEMENT School District of Philadelphia (District) reconciliation procedures for equity in pooled cash and investments1 need to be improved, as District accountants failed to timely detect millions of dollars in errors. Our testing of the account disclosed that the District initially reported a balance of equity in pooled cash and investments at June 30, 2012 that was $66 million higher than bank records indicated on that same date. District accountants were unaware of the error until we brought it to their attention during the audit. Management’s subsequent investigation of the discrepancy disclosed that accountants:

• Failed to detect the improper accounting treatment of the last bi-weekly payroll for fiscal year 2012 by the District’s computerized accounting system, which incorrectly increased the District’s payroll liabilities fund equity in pooled cash and investments account by $30 million. The increase of $30 million should have more appropriately been recorded as a transaction in fiscal year 2013 instead of fiscal year 2012. This error materially misstated the fund’s assets and related liabilities.

• Erroneously recorded a year-end accounting adjustment involving accrued fringe benefit

expenditures that led to a $36 million overstatement in the District’s general fund equity in pooled cash and investments. District accountants made the incorrect adjustment to the books in October 2012.

Once we brought the $66 million discrepancy to management’s attention and they determined the above-described causes with which we concurred, District accountants made the appropriate adjustments to correct the financial statements. While District accounting management asserted that they perform a reconciliation of total funds’ equity in pooled cash and investments to the cash and investment bank balances, it did not appear to be an effective or timely reconciliation since it failed to detect the $66 million of errors. The only reconciliation the District provided to us during our audit fieldwork was a schedule, received in early January 2013, which reflected the revised equity in pooled cash and investment amounts after the $66 million of errors were corrected.

Recommendation: To improve monitoring of equity in pooled cash and investments, we recommend that District accountants periodically reconcile the total funds’ equity amounts to the cash and investment bank balances throughout the fiscal year – preferably monthly but no less frequently than

1 It is a common practice for governmental entities to pool the cash and investments of various funds to improve investment performance. Each fund’s share of this internal investment pool is reported in the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report as an asset titled equity in pooled cash and investments. An important accounting procedure to ensure the accuracy of the reported cash and investment amounts is to reconcile the total balance recorded on the books with the amount held by the bank.

MATERIAL WEAKNESS

2

quarterly. Discrepancies noted should be promptly investigated and resolved. Also, to ensure the accuracy of reported equity in pooled cash and investments, we recommend that the reconciliation be performed as one of the final procedures in completing the fund financial statements. Each reconciliation should be independently reviewed and approved by supervisory personnel. To evidence performance of these tasks and affix accountability, District accounting management should require that documentation be maintained on file for all reconciliations completed [600112.01].

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

3

SAFEGUARDING AND RECORDKEEPING OVER SCHOOL FURNITURE AND EQUIPMENT WERE INADEQUATE The District needs to better safeguard and account for its $272.6 million furniture and equipment inventory. We found nearly 67 percent (87 of 130) of furniture and equipment items selected from District records for testing at eleven different schools could not be located.2 The unlocated items, with a cost value of $196,000, consisted of computers, printers, various audio visual devices, cameras, snow blowers, musical instruments, air conditioners, medical equipment, and athletic equipment. Additionally, we also found that 23 percent of another 90 items chosen haphazardly from furniture and equipment we observed at nine of the eleven selected schools could not be found in the District’s inventory records for the schools.3 These too were items such as computers, a printer, musical instruments, audio visual equipment and a snow blower. Our audit disclosed the following deficiencies and breakdowns in the District’s procedures over its furniture and equipment inventory, which increased the risk of asset misappropriation and contributed to our inability to locate sampled assets and find selected items on the District’s inventory records:

• A new computerized inventory system did not provide for adequate accountability over deleted furniture and equipment.

• District personnel did not maintain adequate records to document what happened to

equipment or furniture left behind in the old facilities when certain schools were relocated to newly constructed facilities.

• District personnel frequently failed to affix school property tags to equipment and furniture.

• Some District personnel removed equipment from school premises without proper

authorization and documentation.

2 For our testing of items chosen from the District’s furniture and equipment records, we selected ten school locations with high dollar amounts of inventory according to the District’s records as of March 27, 2012. The ten selected schools were as follows: West Philadelphia High School, High School of the Future, Edward Bok High School, Overbrook High School, Strawberry Mansion High School, Thomas A. Edison High School, Jules E. Mastbaum High School, Frances E. Willard Elementary School, Warren G. Harding Middle School, and Baldi Middle School. In addition, our sample also included Samuel S. Fels High School, which was tested during the previous audit and required follow-up of prior noted conditions. 3 For the sample of furniture and equipment inventory chosen from observation, we used the same ten school locations selected for the test of items picked from the District’s furniture and equipment records. See note 2 above. During our visit to one of these ten schools (High School of the Future), we were unable to locate any tagged items. Therefore, our test only included a sample of tagged items from the other nine schools. The deficiency regarding various schools’ failure to ensure that furniture and equipment were properly tagged is discussed in more detail on pages 6 and 7 of the report.

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

4

• School personnel frequently did not update their inventory records for furniture and

equipment dispositions.

• Certain schools failed to submit the required annual physical inventory reports for the furniture and equipment located at their facilities.

• Idle equipment observed at a closed school building indicated the District may not always

be optimizing its use of available assets. Each of these deficiencies is discussed in more detail below. New Inventory System Did Not Provide Adequate Accountability over Deleted Furniture and Equipment In fiscal year 2012, the District upgraded its computerized recordkeeping system for furniture and equipment inventory so that personnel at individual schools or units could electronically make changes to their school’s inventory records. Transactions entered by a District school or unit required the electronic signoffs of the designated preparer and the principal or unit administrator. The deletion of items from a school/unit’s inventory records also required the electronic approval of accounting personnel in the District’s Office of Accounting Services and Audit Coordination (OASAC). For certain deletions, such as furniture and equipment less than five years old that was damaged, lost, or stolen, school/unit personnel also had to submit a Serious Incident Report (Form EH-31) before OASAC would approve the removal. However, deletions of items five years or older did not require the submission of any supporting documentation. OASAC management informed us that, for items five years or older which could not be found, school/unit personnel were instructed to delete the items using the “obsolete” disposition code even though there were separate codes which could be used to report damaged, lost, and stolen equipment. Under the new system, the amount of furniture and equipment removed from the District’s inventory records in fiscal year 2012 amounted to $46.3 million, which was more than three times the prior year deletion total of $14.9 million. Of the $46.3 million in deleted furniture and equipment, $44.5 million was coded as “obsolete”. Table 1 on the next page provides a breakout by asset type and age of the $44.5 million in “obsolete” equipment deletions.4 In our opinion, the practice of allowing undocumented deletions increases the chance that thefts of furniture and equipment at District locations can occur and not be detected. Additionally, generic use of the “obsolete” code for these deletions resulted in the District’s inventory records not accurately portraying what happened to certain furniture and equipment. For example, with regard to 28 of the 87 items we were unable to locate – which included computers, printers, a scanner, projectors, an air conditioner, a camera, a camcorder, a saxophone, a piano, a copier, and a television – school personnel removed these items from their inventory records after we visited those schools. Since all 28 items were five years or older, school personnel assigned the “obsolete”

4 The dollar figures presented in this paragraph represent the original cost amounts for the deleted assets. The net carrying value of the fiscal year 2012 deleted furniture and equipment was $1.8 million (original cost of $46.3 million less accumulated depreciation of $44.5 million).

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

5

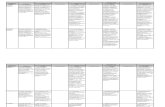

Table 1: Fiscal Year 2012 Furniture and Equipment Deletions Coded as “Obsolete” (amounts in thousands)* Age of Equipment

Equipment Type

5 to 6 Years

6 to 7 Years

7 to 8 Years

8 to 9 Years

9 to 10 Years

Over 10 Years Totals

Computer Hardware &

Software $841 $4,611 $4,644 $3,475 $2,658 $12,721 $28,950 Buses &

Other Vehicles 0 47 0 535 0 5,384 5,966 Furniture &

Fixtures 14 106 80 143 51 4,652 5,046 Musical

Instruments 0 1 1 21 1 1,325 1,349 Audio Visual Equipment 61 247 133 369 99 199 1,108 All Other

Types 33 193 232 227 117 1,235 2,037 Totals $949 $5,205 $5,090 $4,770 $2,926 $25,516 $44,456 Source: Prepared by the City Controller’s Office based on analysis of District furniture and equipment records. *Dollar amounts represent the original cost of the deleted assets.

disposition code to these deletions and thus were not required to submit supporting documentation. However, for 7 of the 28 deletions, school officials had shown us items similar in description to the sampled assets; we could not definitively identify those items because there were no property identification tags affixed to them. Additionally, with regard to 4 of the 28 deleted items, school personnel asserted they had previously disposed of the equipment. When we requested to observe the electronic signoffs of the unit personnel who initiated and approved these 28 asset deletions, OASAC personnel informed us that, due to a limitation with the District’s new system, they were unable to retrieve the history of which employees initiated and approved inventory change transactions. In August 2012, OASAC personnel indicated that they have brought this system limitation to the attention of the District’s Office of Information Technology (OIT). District Personnel Did Not Keep Adequate Records to Document Dispositions of Furniture and Equipment During Relocation to New Facilities In our prior report, we commented that, for certain schools which relocated to newly constructed facilities, District personnel did not maintain adequate records to document what happened to furniture and equipment not moved to the new facility. We again noted this condition during the current audit. As a result, certain schools’ furniture and equipment records were not properly updated to reflect equipment disposals and transfers and, therefore, were not accurate. Two of the schools included in our review – Frances E. Willard Elementary School (Willard) and West Philadelphia High School (West Philadelphia) – moved to newly constructed facilities in September 2010 and September 2011, respectively. When we visited both locations in April 2012, we could not locate and observe 15 of 18 items we chose from the two schools’ furniture and

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

6

equipment records that had been acquired prior to the relocations.5 Officials at both schools failed to supply us with any documentation to support the disposition of the items in question. Subsequently, in July 2012, we requested the deputy chief financial officer (deputy CFO) in charge of the District’s OASAC to provide us with any available records detailing furniture and equipment dispositions during the relocation of the two schools. For the Willard relocation, OASAC provided us with documents, dated October 26, 2010. Those documents had been received and processed by OASAC in March 2012 and indicated that various computer equipment from Willard’s former facility had been transferred to the Spring Garden School and the OIT’s education technology warehouse. From our review of the documents, we could account for only 1 of the 5 items that we had been unable to locate at Willard. However, this item had not been removed from Willard’s inventory records because of an oversight when OASAC personnel processed the relocation documents. When we brought this oversight to OASAC’s attention, its employees adjusted Willard’s records accordingly. In response to our July 2012 request for documentation about the two school relocations, the deputy CFO for OASAC also made inquiries of personnel in the District’s OIT, Facilities and Operations Department, and the Office of Grants Development and Compliance as to what information these units had. In August 2012, OIT furnished OASAC with schedules indicating that several interactive whiteboards and projectors had been removed from West Philadelphia during October 2011 and June 2012 and were either transferred to other schools, stored at the education technology warehouse, or disposed of due to being damaged. OASAC personnel then updated West Philadelphia’s inventory records for these changes. However, none of the ten items we were unable to locate at West Philadelphia were on the schedules submitted by OIT. OIT also provided OASAC with a computer file containing information on West Philadelphia’s computer equipment. However, OASAC personnel stated that the file did not contain usable information for them to update the school’s inventory listing for equipment deletions and transfers. On September 10, 2012, OASAC personnel informed us that they were working with OIT and West Philadelphia officials to clean up the school’s inventory records. District Personnel Frequently Failed to Ensure Furniture and Equipment Were Tagged District Policy 750.0, which establishes procedures over equipment security, requires that all District-owned furniture and equipment be properly identified by affixing a standard property identification tag to it. Property tags are used to track and identify District-owned equipment and serve as a safeguard against theft. As in prior year audits, our visits to selected schools continued to disclose numerous instances of when District personnel failed to ensure that furniture and equipment were tagged. The instances are described below:

• For 42 of the 87 items we could not observe, school officials showed us an item similar in description to the sampled asset. However, we could not positively identify these items as

5 For 6 of the 15 items unable to be observed, school officials showed us an item similar in description to the sampled asset. However, we could not definitively identify these items as the sampled assets because there were no property identification tags affixed to them. The deficiency regarding various schools’ failure to ensure that furniture and equipment were properly tagged is discussed in more detail above.

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

7

the sampled assets because there were no property identification tags affixed to them. Additionally, even though the District’s inventory records listed the manufacturer’s serial number as an available information field, the District’s records did not indicate the serial number in most cases so we were unable to identify the items through use of the serial number.

• During our visit to High School of the Future, we were unable to find any furniture and

equipment with property identification tags affixed to them. According to the District’s inventory records, High School of the Future had a total of 1,282 items valued at $2,365,764.

• In June 2011 during the prior audit, we observed at Samuel S. Fels High School (Fels) a bag

containing 324 property identification tags that were not affixed to any equipment. These tags pertained to various office furniture purchased in fiscal year 2010 at a total cost of $220,000. We again visited Fels in April 2012 and found that the 324 tags had still not been affixed to the related office furniture. School personnel informed us they had a brief description of the related office furniture but did not know where the specific items were located in the school. Also, during our April 2012 visit, we observed that the bag contained three additional tags, which pertained to computer software and instructional aids purchased in June 2009, September 2010, and December 2011 at a total cost of $9,009.

• During a visit to West Philadelphia High School in April 2012 to locate certain equipment

selected from its inventory records, we observed school personnel affixing the identification tags to two selected items – a saxophone and subwoofer that had been purchased in August 2011. Another sampled item – a television purchased in August 2011 – was found still in the box in which it arrived and after eight months had still not been tagged.

• At Warren G. Harding Middle School, we chose from our observations at the school a

tagged printer and discovered that, although its property tag number was located on the school’s inventory records, the equipment associated with the tag number was actually a computer. Therefore, the wrong tag had been placed on the printer.

District Personnel Removed Equipment from School Premises Without Proper Authorization and Documentation District Policies 750.0 (for equipment other than computers) and 750.1 (for computers), require that before removing equipment from a school, employees must prepare and submit specific documentation to the principal for approval. The principal must then retain the documentation. We continued to find that school personnel did not always prepare and submit the required documentation and obtain appropriate authorization when removing equipment from school premises. Specific examples noted during the audit included:

• At High School of the Future, we could not locate a laptop computer selected from the school’s inventory records. School personnel asserted that the laptop had been taken by the previous principal and never returned. They were unable to provide any supporting documentation for the removal of the laptop from the school premises.

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

8

• At High School of the Future, initially we could not locate a sewing machine chosen for

testing. School officials subsequently discovered that an employee had taken a sewing machine off the premises without obtaining the proper authorization from the principal. At the principal’s request, the employee brought the sewing machine back to the school. We returned to the school and observed this sewing machine; however, the item did not have a property identification tag affixed to it.

• During our April 2012 visit to Baldi Middle School, at first we were unable to find a desktop

computer selected for observation. When the school operations officer questioned the teacher in whose classroom the computer was supposed to be located, the teacher stated that she had taken the computer home during the previous summer because of a theft in her classroom during the school year. Our further inquiries revealed that the teacher had removed the computer from the school without submitting the appropriate documentation and obtaining the principal’s approval and then never returned the computer to the school. The school operations officer directed the teacher to return the computer. Upon its return to the school, we observed the computer.

• At Frances E. Willard Elementary School, school personnel informed us that a laptop

computer we could not observe had been taken home by the principal. However, again we determined that the required documentation for removing the computer was not available for inspection at the time of our testing.

School Officials Frequently Did Not Update Inventory Records for Equipment Dispositions To ensure the accuracy of the furniture and equipment inventory records, District policy and procedures require that each District location give an account of all changes to its inventory, including transfers, disposals, losses, thefts, and additions. As discussed in a previous section of this report, in fiscal year 2012 the District upgraded its computerized system for tracking furniture and equipment inventory so that school/unit personnel could electronically make changes to their location’s inventory records. However, as noted in several prior audits, we continued to find numerous instances of when school officials did not take appropriate action to update their inventory records to account for equipment dispositions. Of 7 items we could not observe at four schools visited in April 20126 – a sound module synthesizer, a snow blower, a printer, three computers, and audio visual equipment – school personnel asserted that the equipment had been either disposed of or transferred. However, as of July 2012, officials at the four schools had not taken action to revise their inventory records to reflect these disposals and transfers. Failure of school personnel to properly update their inventory records also contributed to our inability to locate several items selected from observation in the District’s furniture and equipment

6 The four schools were High School of the Future, Edward Bok High School, Strawberry Mansion High School, and Warren G. Harding Middle School.

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

9

inventory records for the schools where we had observed the items. Specific examples noted included:

• For three items chosen from observation at schools – a laptop computer at Edward Bok High School, a smartboard at Thomas A. Edison High School, and an overhead projector at Baldi Middle School – the equipment was eventually located in the inventory records under a different school location.

• At Edward Bok High School (Bok), we observed 90 laptop computers that did not appear in

the inventory records.7 These computers had been transferred to Bok from two other schools but still appeared on those two schools’ furniture and equipment inventory.

• Four computers selected from observation at West Philadelphia High School, Strawberry

Mansion High School, and Jules E. Mastbaum High School, had been incorrectly removed from the District’s inventory of furniture and equipment. These erroneous asset removals occurred because the four computers were recorded in the District’s records under incorrect school locations. School personnel at these locations then directed OASAC to delete the items since the equipment was not physically present at the locations. In all of the instances, District personnel failed to properly update their inventory records to show the assets’ correct locations.

• For 12 items selected from observations at six schools,8 OASAC personnel informed us that

there was no record of the items in the District’s computerized database of furniture and equipment. School personnel had failed to update their inventory records to report the existence of these items.

Certain Schools Did Not Always Submit Required Annual Physical Inventory Reports School principals are directed to perform a yearly inventory of furniture and equipment physically located at their facilities. A properly performed physical inventory is an important control procedure to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the reported inventory. To document its performance, principals are required to submit a physical inventory report, which should be signed by the principal who certifies that the furniture and equipment on the report has been observed and is located at the school. With regard to the eleven schools where we conducted audit testing,9 the following four schools did not submit their physical inventory reports for fiscal year 2012: West Philadelphia High School, High School of the Future, Edward Bok High School, and Samuel S. Fels High School.

7 These 90 laptop computers observed at Bok were not part of our sample of 90 tagged furniture and equipment items selected from observations at nine schools as discussed on page 3 of the report. 8 The six schools were West Philadelphia High School, Edward Bok High School, Strawberry Mansion High School, Jules E. Mastbaum High School, Warren G. Harding Middle School, and Baldi Middle School. 9 See note 2 for a list of these eleven schools.

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

10

Idle Equipment Observed at Closed School Building Suggests the District May Not Always Be Optimizing Use of Available Assets District protocol for closing schools provides general guidelines to be followed in the event of a school building closure and directs school officials to work with District central office personnel in assessing and developing re-distribution plans for various available assets such as furniture and equipment, artwork, and textbooks/instructional aids. However, based upon certain observations made during our audit testing, it appeared that the District’s procedures were not always effective in achieving optimal use of available assets. In light of the serious fiscal challenges facing the District, in our opinion, management needs to make use of every available resource. One of the schools included in our testing – West Philadelphia High School (West Philadelphia) – moved to a new facility in September 2011 after its former building closed in June 2011. When we visited the closed West Philadelphia facility approximately one year later in April and June 2012, we observed several instances of idle equipment and supplies still sitting in this closed school building. Our observations, most of which are illustrated in Appendix I, included the following:

• A classroom still set up as a computer lab containing 22 desktop computers and a printer, which were all powered on and ready for use (Figure 1).

• Various rooms stored numerous additional desktop computers, some of which were in

boxes. Records showed that several of the desktop computers were a little over two years old (Figure 2).

• One room housed a cart with several laptop computers.

• Interactive whiteboards were located in various classrooms (Figure 3).

• An exercise room contained various weight training machines, such as bench presses and a

leg press (Figure 4).

• Various musical instruments were still located in the building, including an organ and four pianos (Figure 5).

• Two artwork items – a bronze plaque and an antique grandfather clock – still remained in

the closed building.

• Several boxes of new textbooks were observed in classrooms and hallways.

• Eight boxes of what appeared to be new band uniforms were stored in the music room (Figure 6).

After we brought our observations to District management’s attention, OIT personnel informed us that the computer lab and interactive whiteboards were set up to temporarily house an alternative education program for District high school students run by a non-profit corporation, whose facility was deemed to need emergency repairs. We observed a School Reform Commission resolution

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

11

authorizing an agreement between the District and the non-profit corporation for the use of the old West Philadelphia building, the term of which ran from October 24, 2011 through November 23, 2011. OIT officials asserted that, once the non-profit corporation’s student program left the old West Philadelphia building in November 2011, the computer lab and interactive whiteboards were left intact during the remainder of the school year in case the space was needed again for another emergency. With regard to the other computers and interactive whiteboards observed, OIT personnel indicated that many of them were older models whose warranty expired so OIT intended to use them for replacements and parts. As for the newer model desktop computers noted, OIT management stated that these units were stored in the closed building until the student success center in West Philadelphia’s new facility was ready to house a computer lab. OIT provided us with a list of 16 computers, all purchased in fiscal year 2010, that were moved to the student success center in June 2012. OIT’s list indicated that two additional computers also scheduled for transfer to the student success center could not be located at the time of the move.

Recommendations:

To improve the safeguarding and recordkeeping of furniture and equipment assets, we recommend that District management contact the principals at the affected schools and work with them to reconcile the remaining differences noted during our testing [600112.02].

To improve controls over its new computerized furniture and equipment inventory system, District management should take the following actions:

• Instruct school/unit personnel that, instead of generically using the “obsolete”

disposition code for equipment deletions over five years old, they must use the disposition code reflecting what actually happened to an item so that inventory records accurately reflect whether items were damaged, lost, or stolen. For items five years or older that are damaged or stolen, school/unit personnel should submit a Serious Incident Report (Form EH-31) [600112.03].

• Given the steep increase in equipment deletions in fiscal year 2012, analyze deletions by location to identify schools/units with large amounts of deletions. Contact the principals or unit administrators at these locations to explain the increase in asset removals [600112.04].

• Revise the computerized system to provide the capability to retrieve the names of the

school/unit employees who initiate and approve each inventory change transaction [600112.05].

• Require that, when a manufacturer’s serial number is available for an item of equipment,

District personnel enter this information into the system’s serial number field to provide an additional way to identify and track equipment [600112.06].

SIGNIFICANT DEFICIENCY

12

In order to properly account for equipment dispositions during school relocations, we continue to recommend the District establish procedures requiring school personnel and other District staff conducting the relocation to maintain records of the furniture and equipment that is not moved to the school’s new facility. These records should list the items by identification tag number and indicate the final disposition of the items, whether scrapped or transferred to another school [600111.06].

To improve safeguarding of furniture and equipment at schools, management should send principals a directive (1) requiring them to contact OASAC to request identification tags for untagged equipment; (2) instructing them to immediately affix identification tags to all equipment once received; (3) advising them of the requirements of District Policies 750.0 and 750.1 regarding the removal of equipment from school premises; (4) reminding them to promptly report all changes in inventory on the computerized furniture and equipment tracking system; and (5) emphasizing the need to comply with established District furniture and equipment procedures for submitting a complete and accurate yearly physical inventory report [600108.01]. To improve utilization of available assets from school closures, we recommend District management provide a directive to school officials and responsible central office personnel detailing the specific steps to be taken in assessing and developing re-distribution plans for available equipment and supplies. District management should monitor compliance with this directive, including visiting the closed facility to ensure that usable equipment and supplies are not sitting idle. Providing detailed procedures for school closures is especially important in light of the many school closures planned at the end of fiscal year 2013 [600112.07].

OTHER CONDITIONS

13

MANAGEMENT OF PETTY CASH REMAINED DEFICIENT In several past reports, we have commented on numerous control weaknesses and instances of non-compliance with established control procedures involving operations of the District’s petty cash funds at the schools. Our visits to six selected schools in April and May 2012 disclosed that schools’ management of these funds continued to be deficient. Observations we made during the visits included finding: (1) significant account shortages; (2) noncompliance with the District’s expenditure policy; (3) inadequate segregation of duties; (4) infrequent account usage; and (5) failure of certain locations to take action to reduce their account balances to authorized levels. These findings, which are discussed in more detail below, adversely affect the District’s ability to properly safeguard and account for its $540,000 petty cash funds.

Significant Shortages Noted For Selected Schools While District accounting records indicated that the six schools we visited should have had total petty cash funds of $20,682.41 in their custody, our review of the schools’ supporting bank and disbursement records only accounted for $6,328.84 of this amount. Therefore, these schools’ petty cash funds were short by a total of $14,353.57, as detailed in Table 2 below. With regard to High School of the Future, we discovered that, while District accounting records at June 30, 2012 carried a petty cash fund balance of $5,000 for this school, its bank account had actually been closed out in September 2008, almost four years ago.

Table 2: Petty Cash Fund Discrepancies Noted for Selected Schools Visited

School

Balance Per

District Records as of June 30,

2012

Balance Accounted

For By Auditor

Account Overage

(Shortage) High School of the Future $ 5,000.00 $ 0.00 ($ 5,000.00) George Pepper Middle School 5,000.00 7.81 (4,992.19) Theodore Roosevelt Middle School 5,164.80 807.34 (4,357.46) Morris E. Leeds Middle School 1,517.61 1,511.49 (6.12) Austin Meehan Middle School 2,000.00 2,002.20 2.20 Woodrow Wilson Middle School 2,000.00 2,000.00 0.00 Total $20,682.41 $6,328.84 ($14,353.57) Source: Prepared by the City Controller’s Office based on analysis of selected schools’ petty cash records

Certain Schools Did Not Comply with the District’s Petty Cash Expenditure Policy Our review of petty cash disbursements at the schools visited disclosed the following instances of non-compliance with the District’s petty cash expenditure policy:

OTHER CONDITIONS

14

• We noted $1,672 in refreshments and other items purchased for various school meetings - $1,478 at Morris E. Leeds Middle School (Leeds) and $194 at Theodore Roosevelt Middle School (Roosevelt) – which District policy did not permit to be paid out of petty cash unless eligible to be reimbursed from available grant funds. In the case of Leeds, these purchases were incurred in fiscal years 2007 and 2008 but had not yet been reimbursed because Leeds failed to submit a reimbursement request before the grant award expired. Additionally, we found that one of Leeds’ refreshment purchases exceeded the $200 petty cash transaction limit. In October 2012, the District’s chief academic officer approved an exception to District policy so the $1,478 of expenditures could be reimbursed by the District’s general fund. With regard to Roosevelt’s $194 purchase, incurred in fiscal year 2008 but not yet submitted for reimbursement, the related imprest fund voucher indicated that the school would request reimbursement from the general fund, which District policy does not permit unless an exception is granted by upper District management.

• At Austin Meehan Middle School, our audit disclosed $105 spent from petty cash funds to

purchase wholesale club store memberships for three school employees to buy goods for student incentives. Our discussion with District accounts payable personnel indicated that this expenditure should more appropriately have been paid out of the school’s student activity funds.

Inadequate Segregation of Duties Was Noted At Selected Schools To reduce the risk of undetected errors and / or theft of funds, proper control procedures suggest that someone other than the petty cash custodian reconcile the fund’s bank account. However, at all five middle schools visited, we found insufficient segregation of duties, noting the fund custodian maintained the checkbook and also reconciled the petty cash bank account.

Selected Schools Infrequently Used Their Petty Cash Accounts Of the six schools visited, only two schools used their petty cash accounts in fiscal year 2012, and that use was very infrequent. At Austin Meehan Middle School and Woodrow Wilson Middle School, which each had a $2,000 fund, there were only six disbursements (three at each school) totaling $749 during fiscal year 2012.

Certain Locations Failed to Reduce Account Balances to Authorized Levels In fiscal year 2008, District management announced plans to reduce the authorized amount of the petty cash imprest funds held at various locations. To reduce each location’s authorized amount, management decided it would process but not repay the locations’ petty cash reimbursement requests until the individual fund balances equaled the revised lower amounts. This practice was ineffective in achieving the desired petty cash reductions because of the large number of funds with low turnover. In November 2009, District management issued a directive instructing location administrators with petty cash funds higher than desired to draw and submit checks to the Accounts Payable Unit in the amount needed to reduce the authorized balances. Despite management’s efforts, as of March 11, 2013, there were still 72 District locations (42 schools and 30 program offices) where the petty cash account balance exceeded the desired authorized amount by a total of $90,819.

OTHER CONDITIONS

15

Recommendations:

With regard to the petty cash shortages found by our audit, District management should take the following actions:

• Work with the affected schools’ personnel to investigate the causes of these shortages and resolve the discrepancies appropriately. If adequate documentation cannot be found to account for the shortages, then District management should request that responsible school personnel reimburse the District for the shortages [600112.08].

• Adjust District accounting records accordingly to reflect the correct petty cash

balances for the affected schools [600112.09].

To enhance internal controls and minimize the risk of undetected errors or theft of petty cash funds, we continue to recommend that the District monitor and enforce policies and procedures relating to the management and reconciliation of all petty cash imprest funds [600108.04].

For all petty cash funds where the planned reduction in the authorized amount has not been completed, District management should enforce its November 2009 directive instructing location administrators to reduce their petty cash funds by paying those monies directly over to the District via a check drawn on the fund’s bank account. Additionally, the District should review the funds for infrequent activity and reduce the authorized amounts accordingly [600112.10].

OVERSIGHT OF STUDENT ACTIVITY FUNDS REMAINED PROBLEMATIC During several previous audits, we reported upon control deficiencies observed in the course of our review of student activity funds at selected schools. Although the District had developed a comprehensive School Fund Manual for student activity funds (Manual), which provided very specific responsibilities and detailed procedures, we found non-compliance with the Manual to be a common occurrence at the schools we visited. In May 2012, we performed a limited review of student activity funds at three high schools – John Bartram High School (Bartram), Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA), and Philadelphia High School for Girls (Girls’ High). Additionally, for 20 schools (the 15 schools with the largest reported cash balances along with 5 other haphazardly selected schools), we examined the fiscal year-end student activity funds financial reports on file in the District’s Office of Accounting Services and Audit Coordination. Our review continued to note non-compliance with the Manual and deficiencies in handling student activity funds, which totaled $5 million for all schools at May 31, 2012. Specifically, we found:

• inadequate procedures over one school activity’s collections; • several instances of expenditures with no supporting documentation; • improper use of student body activity account funds; • non-compliance with bidding requirements; • failure of a principal to review and approve bank reconciliations; • finance committees not being established;

OTHER CONDITIONS

16

• budgets not being prepared by activity sponsors; • activities with negative account balances; • improper retention of school-related funds;10 • failure to close inactive account balances; • long outstanding checks needed better monitoring; and • long outstanding deposits in transit appeared questionable.

Each of these deficiencies, which are discussed below, increases the risk for fraud to occur at the schools and not be timely detected. Procedures Over One School Activity’s Collections Were Inadequate At Bartram, we found inadequate procedures over collections for its student incentives activity which, according to deposit records, totaled $17,422 in fiscal year 2012.11 Collections for the student incentives activity, which were used to fund various student rewards, came from donations received by either the principal or school operations officer, and the sale of t-shirts by the school safety director. When activity sponsors collect money, the District’s Manual requires schools to maintain records that detail the amount, source (e.g. name of student), date received, and purpose of the collection. In spite of this requirement, the principal informed us that no such records were maintained for the student incentives activity. We believe the principal’s failure to require employees responsible for these monies to maintain records in accordance with the Manual created opportunities for the misappropriation of cash. One School Was Unable to Provide Documentation to Support Certain Expenditures The Manual requires that all disbursements from student activity funds be supported by an original invoice and a payment voucher (Form H-201), which the principal signs to evidence approval of the transaction. Our audit disclosed that Bartram school personnel were unable to provide the supporting payment voucher and invoice for expenditures totaling $1,265 – a $1,075 disbursement for a senior class activity and a $190 payment made to a bus company. Also, Bartram officials could not locate the supporting invoices for another $650 of expenditures, which, according to the payment vouchers, included a $150 reimbursement to a student for a stolen cell phone, a $150 purchase of championship game tickets, and a $350 payment to a pizzeria for a student incentive event. Student Body Activities Account Was Improperly Used The Manual requires that funds included in the student body activities account (SBAA) be spent for the general welfare of the student body and states that it is inappropriate to spend these monies on the purchase of normal classroom or office equipment. However, we observed disbursements totaling $2,093 from all three schools’ accounts that appeared questionable. Specifically, we noted the following: 10 School-related funds are monies collected by schools such as fees for transcripts, lost books and equipment, and identification card replacements. While these monies are not considered student activity funds, it is a common practice for schools to deposit, maintain, and disburse these funds from their student activity fund checking accounts. 11 This represents total collections according to deposit records as of April 24, 2012.

OTHER CONDITIONS

17

• At Girls’ High, $1,627 was expended from the SBAA for postage and toner. • CAPA’s disbursement records indicated that $316 of SBAA funds were spent for office

supplies, such as a calendar, toner, and a desk display.

• The unsupported reimbursement to a student for a stolen cell phone discussed above was disbursed from Bartram’s SBAA.

Non-Compliance With Bidding Requirements The Manual’s bidding requirements direct school officials to obtain and retain on file at least three competitive bids for any purchase exceeding $4,000 as well as all yearbook and photography contracts. However, when awarding the yearbook contract in fiscal year 2012, Bartram personnel only obtained two bids. Furthermore, Bartram officials informed us that they did not always solicit bids for the yearbook contract each year and the same vendor had produced the school’s yearbook since 2009. While Girls’ High personnel asserted that they obtained three bids for their yearbook contract, we were only able to observe two of these bids. When schools fail to comply with Manual bidding requirements, there is no assurance that the services are being obtained at a competitive price, and it gives the appearance that the selection process may have been intentionally biased to favor one vendor over others. School’s Principal Did Not Review and Approve Bank Reconciliations The Manual requires that principals review the student activity fund bank reconciliations to ensure their accuracy and identify any errors or irregularities requiring investigation. The principal should sign and date the bank reconciliation form to provide evidence and affix responsibility for the performance of this task. Our inquiries of Bartram’s principal disclosed that she did not review and approve the bank reconciliations. We observed Bartram’s bank reconciliations for the months of July 2011 through March 2012 and found no evidence of principal review. Schools Did Not Establish Finance Committees Student activity fund balances at the three high schools visited totaled $528,871 at May 31, 2012. Because of the significance of these amounts, the Manual requires principals to establish finance committees that advise them on investing cash in excess of current needs. Despite this requirement, Bartram, CAPA, and Girls’ High had not established a finance committee. In addition, we noted that all of CAPA’s funds, which totaled $145,302 at May 31, 2012, were on deposit in a non-interest bearing checking account. Activity Budgets Were Not Prepared At Bartram, budgets that disclosed anticipated income and expenditures were not being prepared on a consistent basis for all activities. According to the Manual, budgets should be constructed as a fiscal management tool for each activity by sponsors, working with student representatives and principals.

OTHER CONDITIONS

18

Negative Activity Account Balances Improperly Created Our review of the fiscal year-end financial reports indicated 11 of 20 schools reported negative equity for at least one type of student activity. This negative equity ranged from ($18) to ($25,001) and totaled ($74,114). The existence of negative balances for individual activities means that expenditures were made even though there were insufficient funds to cover expenses. As a result, the schools used monies from other activities with positive balances to pay for the expenses. This is not permitted under Manual guidance. School-Related Funds Were Improperly Retained School-related funds represent amounts received by schools such as fees for transcripts, lost books and equipment, and identification card replacements. Schools deposit these funds in their student activity accounts and are required to establish separate ledgers to segregate them and facilitate their accounting. The Manual directs that schools remit these fees to the District’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB), who will credit the funds to each school’s operating budget. Our review of the year-end student activity funds financial reports disclosed that, as of May 31, 2012, 14 of 20 schools had not forwarded to the OMB $70,302 in fees related to transcripts, lost books and equipment, and identification card replacements. Inactive Account Balances Were Not Closed Based upon our observations of year-end financial reports, we noted 16 of 20 schools had 174 accounts totaling $135,858 for which there was no activity during the school year. The existence of long dormant balances provides the opportunity to use funds for unauthorized purposes and is addressed in the Manual. According to this guidance, student groups are to designate the use of any funds remaining after each program’s conclusion. In the absence of such designation, excess funds are to be transferred to each school’s student body activities account and used for the general benefit of students. Long Outstanding Checks Needed Better Monitoring The Manual instructs both the principal and school operations officer to monitor outstanding checks as part of the bank reconciliation process. Our review of bank reconciliations submitted with the year-end financial reports disclosed 13 of 20 schools listed checks that had been outstanding for long periods of time (some over 13 years old). In total for all 13 schools, we found 264 checks totaling $22,319 which had been outstanding for over one year. Failure to properly resolve long outstanding checks unnecessarily complicates the bank reconciliation process, and indicates non-compliance with the state’s escheat laws.12 Long Outstanding Deposits In Transit Appeared Questionable Our audit revealed that bank reconciliations for three schools – Julia R. Masterman High School (Masterman), South Philadelphia High School, and Thomas A. Edison High School (Edison) – listed several deposits in transit totaling nearly $10,000 which had been outstanding more than one year. In one case, a $2,011 deposit in transit, which was cited in the last two audit reports, had been

12 The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s escheat laws require that unclaimed property (other than payroll checks) be turned over to the state after remaining unclaimed for five years.

OTHER CONDITIONS

19

listed as outstanding on Edison’s bank reconciliation since July 2001. In another instance, Masterman’s bank reconciliation contained a $7,000 deposit in transit outstanding since January 2010. At the exit conference, District accounting management asserted that, in accounting for adjustments of voided checks on bank reconciliations, school personnel label these adjustments as deposits in transit. However, the District provided no evidence to enable us to determine whether the above deposits in transit carried for so long on the bank reconciliations represented voided check adjustments or missing monies that had been stolen.

Recommendations:

We continue to recommend that principals and school operations officers take steps to comply with guidance described in the Manual to strengthen control procedures and prevent misuse of funds. District management should reinforce the importance of compliance with Manual guidance at the annual training session for principals [600108.03].

Additionally, we again suggest that principals establish control procedures over collections for any activity that generates sales during the year. Activity sponsors should control collections through the use of a cash register or pre-numbered receipts, the information from which should then be reconciled to the counted cash and/or checks. Documentation of this reconciliation should be retained by the activity sponsors and periodically reviewed by the principal [600110.09].

CONTROLS OVER STUDENT TRANSPASS ACTIVITY CONTINUED TO NEED ENHANCING Since fiscal year 2008, the District’s student TransPass program has provided free transportation to Philadelphia public and non-public students by issuing weekly student TransPasses to students living 1.5 or more miles from school, special education students, students participating in desegregation programs and living one mile or more from assigned schools, and students who must cross hazardous roads on their commute.13 Prior reports have disclosed weaknesses and breakdowns in the District’s controls over the distribution and accounting for student TransPasses at individual schools. During the current audit, we performed a limited review of TransPass procedures at five high schools.14 While our current testing disclosed a significantly reduced number of unaccounted TransPasses as compared to the prior audit’s findings, we continued to note some problems with schools’ management of the student TransPass program, which had total expenditures of $35.3 million in fiscal year 2012. Our review of the actual TransPass practices at five selected high schools revealed the following instances of non-compliance with the District’s established procedures for TransPass activity:

• At four high schools – Communications Technical, Germantown, Abraham Lincoln, and Northeast – we observed that the vast majority of TransPass distribution listings were

13 The District purchases student TransPasses from the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA). 14 The five high schools where we reviewed TransPass procedures were the following: Communications Technical High School, Germantown High School, Abraham Lincoln High School, Northeast High School, and Philadelphia Military Academy at Leeds.

OTHER CONDITIONS

20

not signed by the employees who gave out the passes to attest that all students whose name was checked off actually received passes.

• At Philadelphia Military Academy at Leeds, we observed the Summary of Free Student

TransPasses report, which details the number of TransPasses received, distributed, and returned for the month, was not signed and dated by the principal to evidence her review of the report.

Furthermore, at two high schools visited (Germantown and Northeast), personnel who prepared the monthly Summary of Free Student TransPasses report informed us that the reported number of TransPasses distributed was essentially a plug, derived by calculating the difference between the number of TransPasses received and the count of TransPasses to be returned. In order for the monthly Summary of Free Student TransPasses to serve as an effective reconciliation to detect unaccounted TransPasses, personnel should instead determine the amount of TransPasses actually given out by reviewing the distribution listings. For the five schools visited, we reviewed TransPass activity for one selected week15 and, using records provided by each school and the District’s Transportation Services Department, recalculated the number of TransPasses not claimed by students. For each school, we compared our recalculated amount for unclaimed TransPasses to the reported number of unclaimed TransPasses returned to the Transportation Services Department. Table 3 on the next page presents the results of our reconciliation. In total for all five schools, we could not account for 71 TransPasses, which were estimated to cost $1,243.16 While officials at the five schools asserted that employees giving out TransPasses were required to document distribution by either checking off names on the eligibility lists or having students initial or sign the lists, this requirement did not always appear to be followed on a consistent basis. As a result, we could not determine whether the unaccounted TransPasses were a result of improper recordkeeping or irregularities.

Recommendations:

To improve control procedures over TransPass activity and reduce the risk of theft and irregularities, we continue to recommend that the District monitor and enforce policies and procedures relating to the distribution and accounting for student TransPasses [600111.08].

To provide greater accountability over TransPasses, school personnel responsible for preparing the monthly Summary of Free Student TransPasses report should be instructed to determine the number of TransPasses actually given out by reviewing the distribution listings, rather than deriving that number as the difference between the number received and those to be returned. Any unaccounted passes detected from this review should immediately be brought to the attention of the principal and investigated promptly [600111.09].

15 We selected the week of February 6, 2012 through February 10, 2012 for testing, except for Germantown High School where we expanded our review to the entire month of February 2012 because of various differences noted on its monthly Summary of Free Student TransPasses report. 16 The estimated cost figure of $1,243 was calculated by multiplying the price of a five-day student TransPass by the number of unaccounted passes. According to the District’s Transportation Services Department, the price of a five-day student TransPass in fiscal year 2012 was $17.50.

OTHER CONDITIONS

21

Table 3: Auditor’s TransPass Reconciliation for Five Selected High Schools17 Column A High School

Column B

Number of TransPasses

Received Per

Auditor

Column C Number of

TransPasses Distributed

Per Auditor

Column D Number of

TransPasses Unclaimed

Per Auditor

(Col. B – C)

Column E

Number of TransPasses

Unclaimed Per School

District

Column F

Number of TransPasses

Unaccounted (Col. D – E)

Northeast 1,415 1,239 176 129 47 Abraham Lincoln 1,032 815 217 204 13 Germantown 1,474 1,138 336 327 9 Communications Technical 292 277 15 13 2 Military Academy at Leeds 200 197 3 3 0 Total 4,413 3,666 747 676 71 Source: Prepared by the City Controller’s Office based on analysis of the data from the sources listed in footnote 17 below.

FINANCIAL STATEMENT REVIEW PROCEDURES NEEDED MANAGEMENT’S ATTENTION Previously, we reported on deficiencies in the District’s financial statement review procedures. While District accounting management established a formal, written review process for the fiscal year 2011 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR), audit testing had still uncovered accounting errors not caught by this review process. Examples of errors noted included the incorrect reporting of a new asset and mistakes in the calculation of the net assets invested in capital assets, net of related debt. While the net assets computation was very complex and involved numerous adjustments to arrive at the related debt amount, there was no evidence of accounting management review. During the current audit, we observed that District accounting management now documented its review of the net assets invested in capital assets, net of related debt calculation on a written form signed by the responsible accounting manager. Therefore, we consider this prior deficiency resolved [600111.10]. Despite the above corrective action, and the District’s continuation of its formal review process, our current testing still found instances of when District accountants did not catch large mistakes with their review procedures.18 For example, we again noted mistakes in the computation of the net assets invested in capital assets, net of related debt, which resulted in a $9.6 million understatement

17 The sources of information for the TransPass reconciliation presented in Table 3 were as follows:

• Figures in columns B were obtained from the auditor’s review of TransPass receipt/delivery records at the school and the District’s Transportation Services Department.

• Amounts in column C represented the auditor’s count of checkmarks and/or student initials or signatures appearing on the distribution listings provided by school personnel.

• Figures in column E were obtained from the District’s Transportation Services Department.

18 Once we brought these errors to management’s attention, they made the appropriate adjustments to correct them.

OTHER CONDITIONS

22

of this account. Also, our testing of the food service fund’s statement of cash flows disclosed that the reported ending cash balance and cash flow activity were both understated by $5.7 million. District accounting management’s review failed to detect that the statement of cash flows did not include a $5.7 million equity in pooled cash and investments asset – an account which had not shown a reported balance on the food service fund’s year-end financial statements since fiscal year 2006.19

Recommendation:

To further strengthen the District’s procedures for detecting and correcting financial statement errors, we continue to recommend that District management emphasize to personnel responsible for the CAFR review the need to pay particular attention to accounts involving complex calculations and transactions related to new activity [600112.11].

ELIGIBLE COSTS WERE NOT ALWAYS CAPITALIZED Previously, we commented that the District’s capital asset accounting system did not always ensure the capitalization of all eligible capital project fund costs in the year of acquisition, as required by generally accepted accounting principles. As a result, capital assets were understated, and current year expenses were overstated. The prior audit disclosed this condition occurred because of the following:

• The costs for a project involving multiple asset locations were improperly expensed because the responsible District unit did not provide the information necessary to identify the related assets.

• It was the District’s policy not to capitalize furniture and equipment expenditures until

items were tagged with an identification label. We previously reported that District accountants attributed some of the delays in tagging the assets to the extra research required when purchase orders failed to contain sufficiently detailed descriptions of the equipment purchased. Insufficiently detailed purchase orders occurred because the District had not established a formal directive that required units to enter details of purchase requisitions into the accounting system. Our current review disclosed that management issued such a directive to District units on May 16, 2012. Accordingly, we consider our recommendation advising the District to issue a directive regarding purchase requisitions as implemented [600111.05]. However, because the directive was issued towards the end of fiscal year 2012, we will evaluate District units’ compliance with the directive and any resulting effect on equipment tagging in a future audit. Current audit testing found that $4.8 million of fiscal year 2012 information technology (IT) equipment purchases were improperly expensed. District accounting personnel stated these purchases involved networking equipment for which they needed the expertise of the Office of Information Technology (OIT) to determine the specific assets to be tagged and thus capitalized. 19 The District did not report an equity in pooled cash and investments asset for the food service fund during fiscal years 2007 through 2011 because the food service fund had incurred deficits which caused it to overdraw its share of pooled cash and investments. The overdraft was covered by the District’s general fund and properly reported as an interfund payable due to the general fund.

OTHER CONDITIONS

23

District accountants only sent the list of these IT equipment purchases to OIT personnel for review in mid-October 2012. OIT provided District accountants with an analysis of the taggable equipment on January 14, 2013. Since this IT equipment was not tagged by fiscal year-end, the District did not capitalize these assets in fiscal year 2012.20 Our discussions with both District accounting and OIT personnel indicated they planned to implement corrective actions. The OIT manager responsible for analyzing IT related expenditures to determine taggable equipment asserted that fiscal year 2012 was her first year in this role and stated OIT would provide more detailed descriptions for future purchase orders so accounting personnel could more readily identify taggable IT equipment. In addition, District accountants informed us that, in the next fiscal year, they plan to review capital project fund expenditures prior to the close of the fiscal year to identify purchases that may require additional information from other District units so assets can be tagged and capitalized in the year of acquisition.

Recommendations:

To improve capital asset accounting, we recommend that District accountants implement their plan to review capital project fund expenditures during the fiscal year to identify asset purchases that may require additional information from other District units. The information needed from other units should be requested on a timely basis to enable accounting personnel to record the assets in the year of acquisition [600112.12]. District management asserted the extra effort to include the balance of untagged equipment in reported capital asset amounts was not warranted from a cost-benefit perspective because the cost of the untagged personal property was immaterial. We continue to recommend that management annually review the amount of untagged personal property costs to ensure its immateriality in future years [600110.08].