Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

Transcript of Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

-

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

1/24

Returning from Forced Exile:

Some Observations on Theodor W. Adornos

and Hannah Arendts Experience ofPostwar Germany and Their

Political Theories of Totalitarianism

BY LARS RENSMANN

In recent years, the German-Jewish theorists Theodor W. Adorno and HannahArendt have often been described as two of the most important social philosophersand political theorists of the twentieth century. While the former figure had gainedsuch a status by the 1960s, which is to say already during his lifetime, it took until the1980s and 1990s for Arendts multi-faceted work to receive a truly broad reception.By then it had gained its place in the canon of modern political thought, in manyways surpassing Adornos (declining) influence on American and European social

and political philosophy. However, despite many biographical, intellectual andtheoretical affinities, the work of Arendt and Adorno was subject to different, evenmutually hostile cultures of reception. These reproducedand certainly in partemerged fromthe mutual aversion the two eminent intellectuals cultivated duringtheir lifetime.1A posthumous dialogue has only recently begun.2

In spite of the intellectual and personal tensions between them, both Adorno andArendt have also frequently been labelled witnesses of a century, and for goodreasons. Starting in the 1940s, each figure self-consciously acquired the position of apublic intellectual, in the full Gramscian sense: that of an active theoreticianrepeatedly taking sides in contemporary public and political debates. Each thus

became an outstanding international commentator on a century in turmoilacentury shadowed by unprecedented social, cultural and political transformations,new and hideous forms of warfare and, indeed, human catastrophes on anunimaginable scale.

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

1The lack of mutual respect between Arendt and Adorno is documented in their limited correspondenceof 1967; see Library of Congress, Manuscript division, Folder Arendt; for copies see Hannah Arendt

Archive Oldenburg, General Correspondence, Theodor W. Adorno, 1967,7.1; at one point Arendtdescribed Adorno as a half-Jew and one of the most disgusting people that I know and as a string-puller in public campaigns against Martin Heidegger; for these and other such comments on Adornosee Hannah Arendt and Karl Jaspers, Briefwechsel 19261969, Munich 1993, pp. 670, 679 and 673(Arendt to Jaspers, 18 April 1966, 29 April 1966, 4 July 1966).

2The dialogue was initiated with a conference at the University of Oldenburg in 2000 (Witnesses of aCentury); see most recently the approach put forward in Dirk Auer, Lars Rensmann and Julia SchulzeWessel (eds.),Arendt und Adorno, Frankfurt am Main 2003.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

2/24

For both thinkers, the experience of forced emigration from Germany to Americain a quest for refuge from Nazi persecution was crucial.3 But, foremost, it was thecatastrophe of the death camps, or rather its retrospective contemplation, thatinfluenced most of their further thought. The Holocaust, both argued, had forced areadjustment of all philosophical and historical thinking in the West. As Arendt putit, the death camps had exploded the continuum of our history and the terms andcategories of our political thinking.4 In this light, Nazism and modern

totalitarianism soon occupied the centre of Arendts and Adornos theoreticalendeavours and intellectual interventions. For obvious reasons, with both Adornoand Arendt deeply marked by Germanys and European Jewrys fate, the Europeanand especially the German problemcoming to terms with and thinking aboutthe road of European and German history, political culture and the continents andGermanys futurealso became an important focus of their political commentary.This article will discuss some of the reflections offered by the two migrs in response

172 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

3On the intellectual migration of Arendt and Adorno see Anthony Heilbuts instructive Exiled in Paradise:German Refugee Artists and Intellectuals in America from the 1930s to the Present, Cambridge, MA 1993, pp.160174 (Adorno) and pp. 395437 (Arendt).

4Hannah Arendt, Elemente und Ursprnge totaler Herrschaft, Munich 1986, p. 705. It is striking that find thispassage only appears in the German edition.

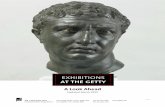

Theodor W. AdornoBy courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute,

New York. Gisela Dischner

Hannah Arendt c. 1936

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

3/24

to their experiences in the Germany of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The articlewill also consider the intellectual processing of these experiences by both intellectualsin the last decades of their careers. I will suggest that their experiences in postwarGermany induced some limited questioning of their own modernist paradigms and

interpretations of the Holocaust, in particular with regard to the role of democraticand anti-democratic mentalities and traditionsbut that they also point to sharedtensions within their approaches to both the twentieth centurys catastrophes and toambivalences in relation to their own German cultural and intellectual heritage.

I

The analytical perspectives that Arendt and Adorno developed in their wartimeAmerican exile largely placed the Nazi dictatorship in the context of modernity. Although Arendts political and Adornos social theory offer quite differentapproaches to a critique of modernity, they also display a great deal of commonground; both theories can be viewed as representative of a critical Europeanhumanism of their time. In general, their modernist approach focused on thedistinctly modern dynamics enabling totalitarian rule, Arendt and Adorno thusemerging as advocates of a universalising approach to Nazism and the Holocaust.Their primary focus is on the historical rise of unprecedented modes of moderncapitalism, bureaucracy and imperialism. Their approaches are linked to themodern experience of permanent change, upheaval and catastrophic loss: an

experience shared with many fellow intellectual migrs. For all of them, the Nazirevolution was of interest less as a specific political-cultural process than as anexpression of the abyss of the modern condition.

In turn, this view is marked by a consciousness of radical insecurity, with bothArendt and Adorno conceptually addressing the rapid political, cultural and socialchanges unfolding in the first half of the twentieth century. The phenomena andevents they addressed ranged from increasingly rapid industrialisation, and theconcomitant evolution of a mass society and mass culture, to the OctoberRevolution, two world wars, and the establishment of three entirely different political

orders in Germany alone: a chaotic historical dynamic transcending all previoussocietal limits and appearing to culminate with the Nazi state and its annihilatoryproject. In light of such a development, for Arendt and Adorno along with manyother European intellectuals, nothing seemed predictable any more, apart frompermanent discontinuity and insecurity.

From such a perspective, modernity came to represent new excessiveconstraints, permanent transformation, and the very unpredictability of the socialworld. With the traditional social order now dissolved, for Arendt as for Adorno, intoan aggregate of reified and atomised masses, individuals, formerly agents of socialaction and rational reflection, were now threatened with absolute powerlessness in

the face of overwhelming social processesat its extreme, with absorption into amachinery following the principles of division of labour and instrumental logic.Totalitarianism and the loss of the world (Arendt) could only take hold under thesedistinctly modern conditions. This is the context for Arendts famous (or, depending

Returning from Forced Exile: Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt 173

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

4/24

on ones perspective, notorious) understanding of Eichmannand with him of thetypical Nazi perpetratoras a petty-bourgeois administrator driven by little ornothing other than a sense of blind bureaucratic purpose and petty career ambitions.It is also the context for Adornos typological definition of the bureaucratic

manipulative character as the ideal-typological Nazi organiser of genocide and,simultaneously, as the ideal type of modern subjectivity.5

To be sure, Arendts idea of totalitarianism and her interpretation of the eclipseof reason followed an independent historical-genealogical pathalbeit one stronglyindebted to Kant and Heidegger. Arendt saw the iron band of terror, ice coldreasoning and the suprahuman logic of nature (Nazism) and history(Stalinism),6 as modern, totalitarian substitutes for expressions of human solidarity,interaction, and reasoning traditionally manifest in both public and private spheres.Totalitarian logic, then, was unique and unprecedented; but it was alsopreconditioned by modernitya kind of radicalization of the same loneliness itseems to have produced.7 This lonelinessin its most modern, radical form, theexperience of a vanished private and public life, indeed of not belonging to the worldat allwas the common ground for terror closely connected with [the]uprootedness and superfluousness which have been the curse of modern massessince the breakdown of political institutions and social traditions in our time.8

Adorno also pointed to a structural atomisation of the individual as a preconditionfor Nazism. His own emphasis was on a lossof individuality and individual experience,rather than on a critiqueof individualisation or privatisation (as argued by Arendt)anemphasis deriving from a socio-economic rather than Arendts political perspective.

However, according to Adorno and similar to Arendts general interpretation,totalitarianism is viewed as the most radical expression of the transformation ofindividuals into powerless masses lacking consciousness and conscience, eager to getinvolved in a totalitarian dynamism. In 1946, he observed that:

Totalitarianism means knowing no limits, not allowing for any breathing spell, conquestwith absolute domination, complete extermination of the chosen foe. With regard to thismeaning of fascist dynamism, any clear-cut program would function as a limitation, akind of guarantee even to the adversary. It is essential to totalitarian rule that nothingshall be guaranteed, no limit is set to ruthless arbitrariness.9

Despite the somewhat different vantage point, this analytic definition has strongsimilarities with Arendts view of the inherent dynamic and drive of totalitarianmovements, implicitly sharing her emphasis on the secondary role played withinthem by specific ideologies.

174 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

5See Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, New York 1965, pp. 2155 andpp. 234279; Theodor W. Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, R. Nevitt Sanford, The

Authoritarian Personality, New York 1982, pp. 355ff.6Hannah Arendt, Origins of Totalitarianism, San Diego, CA 1966, pp. 465ff.7ibid., p. 474.8ibid., p. 475.9Theodor W. Adorno, Anti-Semitism and Fascist Propaganda, in idem, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 8,Frankfurt am Main 1977, pp. 397407, here p. 400.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

5/24

It is important to note that although the strong influence of Kants three critiquesmarks another similarity of Adornos mature perspective with that of Arendt,10Adornowas strongly influenced by the European heritage of Hegelian-Marxist dialecticalmaterialism that Arendt categorically rejected. Nevertheless, the view of totalitarianism

held by both these German-Jewish intellectuals is unmistakably stamped by MaxWebers theory of bureaucratic rationalisationmore specifically, Webers well-knownnotion of an iron cage emerging from modern labour-oriented modes of action,administrative evolution and radical rationalisation. It is as if, in the Holocausts wake,both Adorno and Arendt put aside Webers emphasis on the necessarily ambivalentnatureof this cage, its function as a metaphor of the burden always accompanying the positiveaspects of democratic individualism and the modern sceptical spirit, reading it insteadas a metaphoric encapsulation of a totally reified objective world. In contrast to thisWeberian vision, and in spite of their belief in modernitys post-metaphysicalemancipative potential, for both Arendt and Adorno, the modern condition itself, itsparadigms and culture have led to an alienation between individuals nothing short ofbarbarian.11 For Adorno, the principles of modern society, organised around abstractexchange value, have fostered a subjectivity oriented at control and domination, in theprocess robbing the subject of essential cognitive and moral qualities. In the end, thisleads to in what he terms a subjectivity without subjectivity within a totallyrationalized and socialized society, the universal condition of late capitalism, withblinded men robbed of their subjectivity set loose as subjects.12

Reflecting their shared rejection of any explanations for the Holocaust attemptingto take account of particular historical conditions and dynamics within Germany,

both Arendt and Adorno, emerging from exile, initially strongly defended Germanculture in public statements and private letters. Even later, albeit in the context of acritique of conventional research on national cultures, Adorno would lay emphasistogether with Max Horkheimer on the absence of any German problem, and ofany uniquely German political-cultural issues, furnishing an explanation for eitherNazi-totalitarian antisemitism or the Holocaust. In the straightforward words ofAdorno and Horkheimer, totalitarian anti-Semitism is not a specifically Germanphenomenon. Attempts to deduce it from a questionable entity such as nationalcharacterdownplay the inexplicable that needs to be understood. The problem

needs a social explanation, and this is impossible in the sphere of nationalparticularities.13 Immediately after the Second World War, Arendt used similar ifnot identical language: The real problem is not the German national character butrather the disintegration of that character, or at least the fact that this character doesnot play any role in German politics any more. It is as much a part of the past asGerman militarism and nationalism.14

Returning from Forced Exile: Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt 175

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

10Stefan Mller-Doohm,Adorno, Frankfurt am Main 2003, pp. 493ff, also points out the general lack ofattention to this Kantian dimension of Adornos thinking.

11Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno,Dialectic of Enlightenment, New York 1994, p. 161.12ibid., p. 171 (emphasis added by L.R.).13Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Vorwort zu Paul W. Massings Vorgeschichte des politischenAntisemitismus, in Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 8, Frankfurt am Main 1985, p. 128.

14Hannah Arendt, Das deutsche Problem: Die Restauration des alten Europa, in idem, Zur Zeit: PolitischeEssays, Berlin 1986, p. 31ff.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

6/24

In this respect, it is noteworthy that in preparing the second volume of Origins ofTotalitarianism, completed at the end of 1947,15Arendt had in fact already discussedthe very specific role played by the weakness and collapse of the Weimar Republicsparty system, with its peculiar coalition between the mob and the lite, in the triumph

of Nazism; she had also analysed specific forms of vlkisch-romantic imperialismcentred in Germany and Russiacompensation for a lack of national unity and lostcoloniesthat contributed to the emergence of totalitarian dictatorship. And in 1945,she was one of the first social-political theorists to suggest that the belateddevelopment of the Germans to become a nation and their lack of any sort ofdemocratic experience were important aspects of the Nazi rise to power.16 Thisparticular dimension, however, largely disappeared in Arendts generalised theory ofmodern totalitarianism, as developed in volume three of the Origins, completed in1950, with its strongly universal focus. This is even more the case for the works finalchapter, Ideology and Terror, which Arendt wrote in 1958 for its second edition. Inthe framework of the Cold War, a rather conventional view of totalitarianismresonates here, conceptualising and focusing on parallels between Stalinism andNazism as mere examples of closed modern societies.17A similarly universal andgeneralising approach is evident in Adornos most eloquent and sophisticatedphilosophical text, the Negative Dialecticsof 1966. Here the Holocaust emerges as amaster moral paradigm,18 one leading to a radical adaptation and postwar revisionof the Kantian imperative: In the state of their unfreedom, Hitler has superimposeda new categorical imperative on humans: to adjust their thinking and action in a waythat Auschwitz will not be repeated, that nothing similar will happen.19 Taking

Auschwitz as a new, unprecedented starting point of historical perception and action,this formula is not only tied to revised Kantian cosmopolitan-universalistic premisesbut also embedded in the concept of a general human Verfallsgeschichtean approachto modern history as a negative process reaching its negative climax with theHolocaust. Despite his relentless insistence on historical contingency and possibilityand his explicit challenge to Hegels notion of a universal history,20 Adornostheoretical foundations, as echoed in his Negative Dialectics, themselves represent auniversal Hegelian historical outlook, conceptualising a general historical movementin which the Holocaust is presumably rooted.

In retrospect, it is quite clear that the approach to the Holocaust generallypresented by both Arendt and Adorno reveals many of the limitations of perspectiveinherent in any radically generalising stance. If modern social conditions in generalconstitute the Holocausts main sourcemore specifically, universal socioeconomicconditions (Adorno); modern paradigms of action that have destroyed the res publicaand being in the world (Arendt)then all questions of democratic and legal

176 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

15See Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt: Leben, Werk und Zeit, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p.290.16ibid., p. 28.17See Hauke Brunkhorst, Hannah Arendt, Munich 1999, p. 53.18On a parallel development within the American public sphere, see Jeffrey Shandler, While America

Watches: Televising the Holocaust, Oxford 1999.19Theodor W. Adorno,Negative Dialektik, Frankfurt am Main 1966, p. 358.20ibid., p. 313.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

7/24

theory, the role of political culture and (anti)democratic tradition, human action andresponsibility, and in this case specific German culpability, are in effect left by thewayside. It is equally evident that maintaining such a position made it far easier forArendt and Adorno to return to Germany in the early postwar period without any

strong reservations. I will now argue that although neither Arendt nor Adorno wouldever abandon their basically universalistic intellectual-ethical values, the experienceof this return did lead to a shift, albeit one that was limited, contradictory andfragmented, in their analysis of totalitarianism in generaland of the historical,political and cultural dynamics of the Nazi final solution in particular.

II

Although Arendt clearly remained attached to Germany and Europe and wasconcerned about the fate of both, she found her new home in America and neverreally intended to move back; for his part, Adorno had never given up the hope ofreturn during his exile years.21 He would later on explain that he returned becausehe belonged to Europe and to Germany and simply wanted to return to the placeof his childhood.22 In addition, he had the feeling that in Germany he could dosome good things to help prevent a repetition of disaster.23 He also believed thatGermany would re-emerge as the place where dialectical philosophy could best bepractised; he looked forward to teaching German students committed to thisphilosophy and initially encountered a passionate participation regarding these

questions and matters, a participation that has to make a teacher happy.24 WhileArendt herself made the decision to return to Europe, she would return only forvisits: initially for a longer periodher first return to Europe after the war extendedfrom August 1949 to March 1950then for almost regular, sometimes substantialvisits that went on for the rest of her life, albeit with no consideration of staying. Infact, during her first longer stay in postwar Germany, Arendt felt homesick forAmerica. This visit was commissioned by Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, a newly-founded agency with a centre in Wiesbaden.25 Working at the agency, Arendt alsotravelled across Germany by train and took several journeys across Europeto

France, Germany and Switzerland, where she visited Karl Jaspers in Basel.26

Adornos first return lasted for three years, from the autumn of 1949 to theautumn of 1952.27 He arrived in Frankfurt on 2 November 1949 and was

Returning from Forced Exile: Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt 177

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

21Theodor W. Adorno, Auf die Frage: Warum sind Sie zurckgekehrt, in idem, Gesammelte Schriften,vol.20.1, Frankfurt am Main 1986, pp. 394395, here p. 394.

22ibid., p. 395.23ibid.24Theodor W. Adorno, Die auferstandene Kultur, in idem, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 20.2, Frankfurt am

Main 1986, pp. 453464, here p. 454.25See Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt: Leben, Werk und Zeit, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 344.26ibid., p. 337 and p. 305.27See Rolf Wiggershaus,Die Frankfurter Schule: Geschichte, theoretische Entwicklung, politische Bedeutung, Munich

1988, pp. 507f; for a more recent and more extensive account see Detlev Claussen, Theodor W. Adorno:Ein letztes Genie, Frankfurt am Main 2003, pp. 240ff and Mller-Doohm, pp. 496ff.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

8/24

immediately confronted with heavy professional responsibilities.28 From the onset,his time in Frankfurt partly served to prepare his remigration and the re-establishment of the Institute for Social Research, which soon came to be envisionedas Germanys new central sociological research institutionsomething promised by

Adornos close friend and fellow remigr Max Horkheimer.29 During this timeAdorno taught philosophy classes and lectured at the University of Frankfurt; he alsoconducted or participated in several empirical studies, including a study of thecommunity of Darmstadt and its rural surroundings and the Group Experiment, aqualitative study of German postwar attitudes towards Nazism, re-education, andGerman guilt.30As a naturalised American citizen, Adorno was forced to return tothe United States in October 1952 in order not to lose his American citizenshipwhich he strongly wanted to keep. Deeply committed to the idea of re-establishingthe Frankfurt institute together with Horkheimer, he left with an endlessly heavy

heart,31

travelling via Paris to New York and Los Angeles. He would only remainten months before finally resettling in Frankfurt in August 1953, eventually beingappointed supernumerary professor for philosophy and sociology.32 Following thissecond remigration Adorno would never return to America.

Despite all its recent horrors, Arendt and Adorno both initially arrived in Europeand Germany with a sense of hope for the possibilities of the countrys political andmoral renewal, and a sense of belief in the cultural and human resources for suchrenewalfeelings that inform several of their early postwar essays and writings.33

Immediately after his return to the German classrooms, Adorno praised theintellectual passion34 of his German philosophy students, as documented in an

essay of 1950 called Die auferstandene Kultur (The resurrected culture), thoughAdorno simultaneously acknowledged that the students apolitical Vergeistigung, theirorientation towards philosophical and spiritual matters, might be considered anambivalent process from a democratic perspective.35 In 1965 Adorno would lookback on such early sentiments regarding his native country:

At no moment during my emigration did I relinquish the hope of coming back. Andalthough the identification with the familiar is undeniably an aspect of this hope, itshould not be misconstrued into a theoretical identification for something that probablyis legitimate only so long as it obeys the impulse without appealing to elaborate

theoretical supports. That in my voluntary decision I harboured the feeling of being ableto do some good in Germany, to work against the obduration, the repetition of thedisaster, is only another aspect of that spontaneous identification.36

178 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

28See Claussen, p. 242.29Wiggershaus, p. 514; Horkheimer to Adorno, 13 March 1953.30ibid, p. 504 and p. 526.31ibid, p. 508; Adorno to Horkheimer, 20 October 1952.32ibid, p. 520.33See two texts written by Arendt in 1945: Approaching the German Question, in idem, Essays in

Understanding 19301954, ed. by Jerome Kohn, New York 1994, pp. 97126; The Seeds of a FascistInternational, ibid., , pp.140150; for Adorno see two texts written in 1949: idem,Die auferstandeneKultur; Toward a Reappraisal of Heine, in idem, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 20.2, pp. 441452.

34idem, Die auferstandene Kultur, p. 453.35ibid.36Theodor W. Adorno, On the Question: What is German?, in idem, Critical Models: Interventions and

Catchwords, New York 1998, pp. 205214, here p. 209.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

9/24

Furthermore, at the onset of his return it appeared to Adorno, as if in Germany,of all places, an autonomous culture would still be possible and not only a lostidealistic illusion emerging from a German tradition.37 Adorno was not onlyinitially enthusiastic about his new German students, these young people, the

academic youth, as he wrote to Thomas Mann in a letter dated 28 December 1949;in general, the intellectual climate in Germany appeared to him quite seductive,as he explained to Horkheimer in a letter written one day later.38 Adorno waslooking forward to teaching German philosophy to committed native students, andin German, the only language he considered fully suitable for dialectical-speculative,anti-positivistic thinking.39 Following his successful escape and survival in exile, healso hoped to finally find conditions that would, as he put it, impair his work as littleas possible40conditions he deemed only present in his native environment. On atheoretical and political level, it is worth noting his recollection that the conceptionthat the Germans as a people are guilty was alien to me and his insistence thatNazism should not be seen as deriving from a German national character.41

In contrast to Adorno, Arendt, as indicated, never seriously considered moving backto Germany permanently. Still, she herself expressed her desire and commitment tohelp the Germans build a new societyone based on a truthful acknowledgment andworking through of the past.42 This desire and commitment, apparently driven by afirm if ambivalent affection for her society of origin, is documented in private lettersand attested to in her carefully thought out decision to return temporarily to Germanyand engage in difficult Hundsarbeit43 for Jewish Cultural Reconstruction.

In Germany, however, neither Arendt nor Adorno were offered the reception they

expected, each instead encountering a society that maintained a collective narcissismof a nationalist nature: one whose basic values were still heavily influenced byNazism and that, in fact, harboured strong hostility towards all Jewish returnees. Theresponse to this encounter on the part of both German-Jewish intellectuals was anincreasingly sharp analysis of the particular social, psychological and politicaldynamics manifest in the postwar West German scene; the response was presentedmost pointedly by Arendt in her well-known essay, The Aftermath of Nazi Rule:Report from Germany (1950), and her observations concerning the Auschwitz trials,Der Auschwitz-Prozess (serving as an introduction to Bernd Naumanns book

Auschwitz, published in 1966);44

and by Adorno in his dissection of German society

Returning from Forced Exile: Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt 179

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

37Claussen, p. 243.38Cited in Mller-Doohm, p. 504. On Adornos correspondence with Thomas Mann see ibid., pp.

474489.39Adorno, On the Question: What is German?, pp. 212f.40See ibid., p. 211. Adornos former colleagues at the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Leo

Lwenthal and Herbert Marcuse, chose to stay in the United States.41 Adorno, Auf die Frage: Warum sind Sie zurckgekehrt, p. 394; see also Alex Demirovic,Der

nonkonformistische Intellektuelle: Die Entwicklung der Kritischen Theorie zur Frankfurter Schule, Frankfurt am Main1999, p. 99f.

42 Arendt, Approaching the German Question, in idem, Essays in Understanding, pp. 97126, pp.114;Hannah Arendt to Karl Jaspers, 17 August 1946, in Arendt and Jaspers, Briefwechsel, p. 89.

43See Young-Bruehl, p. 344.44Hannah Arendt, Preface, in Bernd Naumann, Auschwitz, New York 1966; published in German asArendt, Der Auschwitz-Prozess, in idem,Nach Auschwitz: Essays und Kommentare I, Berlin 1989, pp. 99136.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

10/24

entitled Schuld und Abwehr (Guilt and Defensiveness) as well as his broadlyreceived, most prominent critical intervention with the Kantian title Was bedeutet:Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit (The Meaning of Working through the Past).45

In her Report from Germany, Arendt came to terms with her experience of

living for six months in postwar Germany. She expressed shock at what she describedas a particular kind of German escapism. Willingly or unintentionally, she indicated,in so far as it might harm their idealistic collective self-image, the Germans she metavoided any serious confrontation with political and historical reality, constantlydisplaying a continuous totalitarian relativism towards historical facts, in other wordsthe habit of treating facts as though they were mere opinions. For example, thequestion of who started the last war, by no means a hotly debated issue, is answeredby a surprising variety of opinions. An otherwise quite normally intelligent womanin Southern Germany told me that the Russians had begun the war with an attackon Danzig; this is only the crudest of many examples.46

Arendt described time and again encountering people who still debated historicalfacts about the war, the concentration camps, and other historical realities in apseudo-democratic re-enactment of public arguing. The average German, shestated, honestly believes this free-for-all, this nihilistic relativity about facts, to be theessence of democracy. In fact, of course, it is a legacy of the Nazi regime.47 Ingeneral, Arendt realised that the truth about the death camps was publicly andprivately ignored, and any collective or individual responsibility was fiercely denied.Arendt noted that a ubiquitous absence of response to what happened is evidenteverywhere, adding that:

It is difficult to say whether this signifies a half-conscious refusal to yield to grief or agenuine inability to feel. And the indifference with which they walk through the rubblehas its exact counterpart in the absence of mourning for the dead, or in the apathy withwhich they react, or, rather, fail to react to the fate of refugees in their midst. This generallack of emotion, at any rate this apparent heartlessness, sometimes covered over withcheap sentimentality, is only the most conspicuous outward symptom of a deep-rooted,stubborn, and at times vicious refusal to face and come to terms with what reallyhappened.48

As a response to any references to recent history or ones own Jewish origins, Arendtobserved, people proceed to draw up a balance between German suffering and thesuffering of others, the implication being that one side cancels the other and we mayas well proceed to a more promising topic of conversation.49 Hence the mostcommon publicly expressed emotion Arendt was able to observe was self-pity, with Allied policies consistently seen as aimed at revenge, not democratisation. In

180 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

45Theodor W. Adorno, Schuld und Abwehr: Eine qualitative Analyse zum Gruppenexperiment, inidem, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 9.2, Frankfurt am Main 1975, pp. 121324; Theodor W. Adorno, TheMeaning of Working Through the Past, in idem, Critical Models, pp. 89104.

46Hannah Arendt, The Aftermath of Nazi Rule: Report from Germany, in idem, Essays in Understanding,pp. 248269, here p. 251.

47ibid., p. 252.48ibid., p. 249.49ibid.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

11/24

conclusion Arendt argued that German industriousness served as an effective tool inthe countrys sheltering of itself against the Nazi legacy and the political and moralchallenges of the time. Indeed, this present industriousness was in reality a drive torestore an idealised past, a drive crystallised in the word Wiederaufbau; it fuelled

Arendts impression at first glance that Germany is still potentially the mostdangerous European nation.50 Arendt encapsulated her report in an observationfusing objective history with subjective experience: And one wants to cry out: Thisis not realreal are the ruins; real are the past horrors, real are the dead whom youhave forgotten. But they [your addressees] are living ghosts, whom speech andargument, the glance of human eyes and the mourning of human hearts, no longertouch.51 However, while emphasising the specificity of the German situation, Arendts negative experience also reached, to some extent, beyond Germanysborders. In general, she was shocked by the moral chaos in Europe in toto, onlyEngland appearing to her as a country that survived the war morally intact.52

Among Arendts trips to Germany and elsewhere in Europe that followed herlong-term sojourn, the following are particularly noteworthy: a visit to Germanyfrom April to September 1952, this time with private funding, and with the task ofhelping with the reconstruction of German philosophical studies;53 a visit to KarlJaspers in the autumn of 1956 and a trip to Frankfurt in October 1958 to present thelaudatio for Jaspers, who was receiving the prestigious Peace Prize of GermanBooksellers; a trip to Hamburg in 1959 to receive the citys prominent Lessing Prizefor the humanistic and enlightened nature of her work; another trip to Darmstadt inSeptember 1967 to receive the Sigmund Freud Prize for Academic Prose of the

German Academy for Language and Poetry, awarded to Arendt not for her (verylimited) admiration of Freuds work but because of her extraordinary contributionsto the German language, praise she clearly appreciated;54 and finally, a trip toCopenhagen in April 1975 to accept the Danish governments and the University ofCopenhagens prestigious Sonning Prize, awarded for major contributions toEuropean culture. (Arendt received the award on 18 April 1975 for her work as ahistorian of totalitarian systems and as a political theorist; she was the first Americancitizen and the first woman to receive the prize.)55 She also built new friendships withEuropean and German colleagues, re-established some old onesmost prominently

she always kept close contact with Karl Jaspersand even participated in Germanyspublic and academic life through her many publications, commentaries, andspeeches. Right from the start, the visits to Karl and Gertrude Jaspers in Basel hadmade her even feel at home in Europe, both philosophically and personally,

Returning from Forced Exile: Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt 181

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

50ibid., p. 254.51ibid.52See Young-Bruehl, p. 345.53ibid, p. 380 and p. 394.54In a letter to Dr. Johan, the president of the academy, Arendt wrote: I was forced to leave Germany 34years ago; my mother tongue was everything that I could take with me from my old home, and I alwaysmade great efforts to keep this irreplaceable treasure intact and alive. The Academys award is like arecognition that I succeeded in doing it. Arendt to Johan, 6 July 1967; quoted in Young-Bruehl, p. 535.

55ibid, p. 626 and p. 630; see also Ingeborg Nordmann, Hannah Arendt, Frankfurt 1994, p. 137.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

12/24

especially personally.56 At the same time, until her death in 1975 she kept aconsiderable distance from Germanys official policies and prevailing social mood:she strongly criticised the German governments reluctance to accept decisions bythe United States and the other Allied powers (for example, the decision to build a

European Defence Community in May 1952), a reluctance she began toconceptualise as stemming from an evil nationalism of the German people;57 andshe criticised the continuous German initiatives to legislate statutes of limitation forNazi crimes, as well as the general lack of willingness by the German governmentand German courts to prosecute Nazi criminals.58 In a letter published by theGerman weeklyDer Spiegel, in 1965 she wrote that Germans might well react to thethought of living with murderers of cab drivers by restoring the death penalty;59

but when it came to crimes of previously unheard of proportions, no one seemed toshow any emotional reaction, let alone anger or outrage.

Adornos experiences and analysis of the postwar mentality in Germany wasstrikingly similar to Arendts. In Adornos case, the analysis was backed up withsystematic social researchthe Group Experiment, his qualitative study of Germanguilt feelings and defensive mechanisms in respect to Nazi crimeswhich served asthe basis for a set of theoretical interpretations of postwar German reactions to theHolocaust.60 The study involved group discussions held among Germans fromvarious social backgrounds with a range of occupations and ages. The participantswere given a letter ostensibly written by an American soldier; in the letter he bothcriticised German authoritarianism and the way Germans had been dealing with therecent past and praised the Germans for their cultural achievements and capabilities.

The general response to the letter revealed strong affective reactionsin particularwhat Adorno defined as a collective defensiveness regarding German national guiltand political responsibility, as well as the guilt of specific German perpetrators. Theresponse appeared to be as strong among participants who were evidently personallyinnocent as among former members of the Nazi party, and efforts to denycollective, national responsibility appeared even more affectively loaded than thoseto deny personal guilt.

In his analysis of the findings, Adorno discerned seven major themes anddifferentiated between two major reaction-patterns among the participants. On the

one hand, the vast majority had a strong sense of German national identity andreacted defensively and aggressively when confronted with German crimes. Allfarmers participating in the study, as well as virtually all academics, denied any guilton the part of Germany or the Germans. Almost ninety per cent of the latter group

182 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

56Hannah Arendt to Fritz Frnkel, 20 December 1950, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Arendtfolder.

57Hannah Arendt to Heinrich Blcher, 30 May 1952, ibid.58See, for example, Arendts preface to Karl Jaspers, The Future of Germany, Chicago 1967.59Hanna Arendt to editors of Der Spiegel12 February 1965, Hannah Arendt Archive Oldenburg,

Catalogue: Publishers,Der Spiegel19651970, 32.5.60For a brief overview of the studys empirical results see Lars Rensmann, Collective Guilt, National

Identity, and Political Processes in Contemporary Germany, in Nyla Branscombe and Bertjan Doosje(eds.), Collective Guilt: International Perspectives, Cambridge 2004 [forthcoming]; for a more extensiveanalysis see Lars Rensmann, Kritische Theorie ber den Antisemitismus, Hamburg 1998, pp. 231288.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

13/24

was either somewhat or radically antisemiticalthough academics were oftenreluctant to speak up about the topic.61 On the other hand, a small minority of thoseinterviewed identified less with the national collective. While itself revealingdefensive reactions to a lesser degree, this minority (sixteen per cent) was relatively

open to acknowledging German guilt and more frequently supported the idea ofcompensation for the victims. But despite these scattered exceptions the studyunderscored a widespread pattern of defensive strategies such as equating theHolocaust with crimes committed by the others. These strategies wereaccompanied by continued strong identification with Germany as a self-evidentlysuperior nation, as well as frequent projection of personal guilt onto both the Alliedforces and, above all, the Jewish victims and survivors: a process expressed in what Adorno defined as a secondary antisemitism motivated by identifying the Jews asrepresentatives of an unwanted and unmastered memory. Adorno argued thatGermans holding such attitudes in fact simultaneously clung to authoritarianism anddeep-seated prejudices and clichs regarding virtually every minority, while everystatement about the Germans is defensively rejected as an illegitimate falsegeneralisation.62A cognitive incapacity to judge and evaluate historical processes oreven get the basic historical facts straight, strong national identifications and highlevels of prejudice, a general lack of empathy towards the victims, a high degree ofnational and individual self-pity to the point of viewing the Germans as the real victims of Nazism and the Second World War such traits, Adorno concluded,amounted to nothing less than a general social tendency towards an irrational,aggressive defensiveness, a transsubjective factor characterising early postwar,

post-totalitarian West German society and culture.63 Adorno thus discovered whathe termed a social objective spirit, amounting to a new German ideology.64

It is striking that interspersed throughout Adornos two hundred-page empiricalmaterial, we find expressions of personal anger, and even shock, at the responses of various participants in his study. Like Arendt, Adorno, who as indicated hadcelebrated the capabilities of his new German students a short time before, wasunmistakably surprised and affected by the level of aggression, prejudice and denialhe encountered on an unexpectedly broad scale. It was as if, as Arendt later put it inEichmann in Jerusalem, German society and its prevailing moral system were not

shared by the outside world65

and were still a world apart from the rest ofcontemporary civilisation.

For Adorno, it appears that things did not get better in the 1950s; he experiencedthis static situation both personally and, more so, in his professional life in which hehad invested so much hope. Against his expectations, he was not welcomed home byGermanys academic community: like many other German-Jewish academic exiles,he initially received no adequate professional appointment (though he was invited toteach classes at the Philosophy faculty of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of

Returning from Forced Exile: Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt 183

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

61Wiggershaus, p. 490.62Adorno, Schuld und Abwehr, pp. 121324, here pp. 218f.63ibid., p. 138 and p. 146.64Draft manuscript by Adorno cited in Wiggershaus, p. 489.65Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, p. 103.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

14/24

Frankfurt between 1949 and 1952),66 and was finally offered a supernumerary chairin August 1953 by Frankfurt University as a result of pressure exerted by MaxHorkheimer after Adorno had spent another year in the US. Addressing AdornosJewish background and migr status, the dean of the philosophical faculty declared

that such a chair would be established for Adorno solely for reasons of restitution.67A number of his university colleagues, many appointed by Nazi university presidents,viewed Adornos position as a privilege granted because he was Jewish; his restitutionchair thus became aJudenprofessura Jews professorship.68 In any event, until July1957 his hopes of becoming a regular full professor remained unfulfilled.

In February 1956, Adorno was forced to remind the dean of philosophy of hisright to become a full professor according to the third revision of the Law for theRestitution of National Socialist Injustice. Many colleagues in the Philosophyfaculty (which, following the German tradition, included the humanities in their

entirety) objected. One of the most distinguished colleagues, Hellmut Ritter, aprofessor of oriental history, claimed in a meeting of the commission founded todeal with the Adorno case that in Frankfurt you only need to be promoted byMr. Horkheimer and to be a Jew in order to have a career.69 Ritters voice wasrepresentative of many, and of a generally hostile climate facing Jews in thePhilosophy faculty and in various departments throughout the university.70 Thisclimate largely shattered Adornos hopes for a fresh start for German society andculture that could revive its best traditions; the steady frustration caused byexperiences of ostracisation and inflicted resentment soon led to a fading of thehigh ambitions tied to the re-establishment of the Frankfurt institute. In May 1956,

Adornos friend and mentor Horkheimer officially applied for retirement because ofthe hatred against Jews expressed by his colleagues.71 To be sure, both Adornoand Horkheimer seemed to be encountering more hostility within the academythan outside it, where Adorno quickly re-established old friendships and formednew ones.72 Still, even when he finally received his Ordinariustitle on 1 July 1957, hedid not enjoy an ordinary professorship at Frankfurt; and at that point, he was notfully satisfied with the appointment, as its terms could not be improved on throughthe presence of similar offers from other German universities (he would receive nosuch offers during the remaining years of his career).73 In 1959, Adorno laid out the

conclusions drawn from his previous research, and even more so, from hisaccumulated experience inside the academy and in German society as a wholeduring the 1950s in his essay Was bedeutet: Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit (TheMeaning of Working through the Past), an essay that remains one of the mostradical critiques of postwar West Germanys approach to coming to terms with the

184 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

66See Mller-Doohm,Adorno, p. 507.67Wiggershaus, p. 520.68ibid.69ibid., p. 521.70ibid.71ibid.72Mller-Doohm, p. 526.73Wiggershaus, p. 521.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

15/24

past. Adorno here drew a stark portrait of a society in which National Socialismlives on, where even today we still do not know whether it is merely a ghost ofwhat was so monstrous that lingers on after its own death, or whether it has not yetdied at all, whether the willingness to commit the unspeakable survives in people as

well as in the conditions that enclose them.74 Within this framework, he criticisedan omnipresent desire to break away from the past, with its concomitant full-scalepublic destruction of memory75 a widespread indifference towards what hadtranspired that he identified with as much acuity and indignation as had Arendtalmost a decade earlier. Adorno argued:

There is much that is neurotic in the relation to the past: defensive postures where one isnot attacked, intense affects where they are hardly warranted by the situation, an absenceof affect in the face of the gravest matters, not seldom simply a repression of what isknown or half-known. We are also familiar with the readiness today to deny or

minimize what happenedno matter how difficult it is to comprehend that people feel noshame in arguing that it was at most only five and not six million Jews who were gassed.

Responsibility for Hitlers crimes and the Nazi disaster, he continued, is shifted ontothose who tolerated his seizure of power [i.e. England and America] and not to theones who cheered him on. The idiocy of all this is truly a sign of something thatpsychologically has not been mastered, a wound, although the idea of wounds wouldbe rather more appropriate for the victims.76 What had not been mastered, heconcluded, was a persistent collective narcissism: an ongoing identification with anidealised image of the nation as a huge collective self. Secretly, smouldering

unconsciously and therefore all the more powerfully, Adorno suggested, theidentifications and collective narcissism stamping the Hitler years were thus notdestroyed at all, but continue to exist.77

Although in many respects Hannah Arendts interpretation of the Holocaust,totalitarianism, and the post-totalitarian constellation in Germany did differ fromAdornos, as has been suggested in these pages, in other respects we can also findstriking similarities in relation to the German problem, some of these apparentlyrelated to similar postwar observations and experiences. On the one hand, her timein postwar Germany did not induce her to revise her view of the modern condition,

and of totalitarianism as to a great extent a modern phenomenon, rooted inuniversal modern developments such as imperialism and atomisation in mass society.She continued to interpret antisemitism as an essentially supranational politicalideology that needed to be approached in terms of its general social and politicalorigins, in other words as a powerful weapon in organising the rootless, atomisedmasses of modernity.78 With the publication of her Eichmann book in 1963, sheeven seemed to go so far as to describe the Holocaust as essentially an abstractadministrative procedure carried out by thoughtless bureaucrats, rather than by

Returning from Forced Exile: Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt 185

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

74Theodor W. Adorno, The Meaning of Working Through the Past, p. 90.75ibid., pp. 89 and 91.76ibid., p. 91.77ibid., p. 96.78See Richard J. Bernstein, Hannah Arendt and the Jewish Question, Cambridge, MA 1996, p. 70.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

16/24

fanaticised followers of a demented political and cultural ideology. Some of herobservations on Germany in the wake of the Holocaust appear to reflect her thesisthat a totalitarian system destroys the moral and cognitive competence of itsmembers: the situation in postwar Germany, Arendt argued, also demonstrates that

totalitarian rule is something more than merely the worst form of tyranny.79 Theexperience of totalitarianism, Arendt claimed, had robbed the Germans of allspontaneous speech and comprehension, so that now, having no official line to guidethem, they are, as it were, speechless, incapable of articulating thoughts andadequately expressing their feelings.80

On the other hand, it is possible to discern a new epistemological position inArendts writings of the postwar period: an insight into the importance of socio-cultural, political, anti-democratic traditions, and, in particular into theunwillingness of most Germans to deal with the Nazi legacy; the isolation of acontemporary West German predisposition to coldness, indifference and insensitivitythat she defined as anti-democratic.81 The deep moral confusion apparent inGermany today, then, is more than amorality and has deeper causes than merewickedness. The so-called good Germans are often as misled in their moraljudgements of themselves and others as those who simply refuse to recognize thatanything wrong or out of the ordinary was done by Germany at all.82 In suchpassages, Arendt expressed her own surprise at the depth of the destruction ofGermanys prewar public and private life83at the extent of the anti-democratictraits maintained by accomplices to unspeakable crimes,84 and especially at thewidespread repression of recent history and outright hostility she encountered as a

German-Jewish exile.85 In an attempt to link her general theory of totalitarianism toan analysis of specific historical traits and traditions, Arendt critically reconstructedthese particular attitudes, for example as manifest in a prevailing bustling activitythat she saw not as the reflection of a fixed national character but rather as onesymptom of a deep-seated historically determined mentality.86 It was a well-knownfact, she indicated, that Germans have for generations been overfond ofworking.87 However, watching the Germans busily stumble through the ruins of athousand years of their own history, shrugging their shoulders at the destroyedlandmarks or resentful when reminded of the deeds of horror that haunt the whole

surrounding world, one comes to realize that busyness has become their chiefdefence against reality.88 For Arendt, then, such bustle and escape fromresponsibility89 and associated postwar defensiveness in the face of industrial mass

186 Lars Rensmann

1234

567891011121314151617181920212223

242526272829303132

3334353637383940414243444546

79Arendt, The Aftermath of Nazi Rule, p. 269.80ibid., p. 253.81ibid, p. 268.82ibid, p. 259.83ibid., p. 259f.84ibid., p. 261.85Hannah Arendt to Fritz Frnkel, 4 February 1950, Manuscript Division, Folder Arendt, Library of

Congress.86Arendt, The Aftermath of Nazi Rule, p. 261.87ibid.88ibid., p. 254.89ibid., p. 250.

atLeicesterUniversityLibraryonApril29,2010

http

://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org

Downloadedfrom

http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ -

8/4/2019 Rensmann Returning From Forced Exile

17/24

murder corresponded to the process through which the Nazi murder machine keptgoing.90At one point, she ironically remarked to Fritz Frnkel that The Germansare working their brains off (die Deutschen arbeiten sich dumm und dmlich).91

In Adornos postwar writing, and in light of his postwar experiences, one likewise

finds elements of an increasingly specified approach to the interlinking questions ofhow to define the role of German antidemocratic traditions and what caused theHolocaust. As the following remarks reveal, this development culminated in a complexand critical version of the Sonderwegthesis that was rooted in social psychology:

Because historically German unification was belated, precarious, and unstable, one tends,simply so as to feel like a nation at all, to overplay the national consciousness and irritablyavenge every deviation from it. In this situation it is easy to regress to archaic conditionsof a pre-individualistic disposition, a tribal consciousness, to which one can appeal with allthe greater psychological effectiveness the less such consciousness actually exists.92

In the same context, Adorno juxtaposed Germanys dominant blind dependencies,which include the unreflected supremacy of the national with another,universalistic tradition originating with Kant, whose thought centered upon theconcept of autonomy, the self-responsibility of the reasoning individual.93 In theyears after his return to Germany, Adornos focus would correspondingly turn to thespecific relationship between anti-modern sentiments and authoritarian ideologiesanchored in German political-cultural history, on the one hand, and the processes ofcapitalist modernisation and totalisation of the iron cage of modernity in thetwentieth century, on the other.