Remains of Giant Irish Deer (Megaceros giganteus) from Larne Lough Co. Antrim

-

Upload

peter-francis -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Remains of Giant Irish Deer (Megaceros giganteus) from Larne Lough Co. Antrim

Remains of Giant Irish Deer (Megaceros giganteus) from Larne Lough Co. AntrimAuthor(s): Peter FrancisSource: The Irish Naturalists' Journal, Vol. 20, No. 6 (Apr., 1981), pp. 240-243Published by: Irish Naturalists' Journal Ltd.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25538492 .

Accessed: 14/06/2014 15:43

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Irish Naturalists' Journal Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The IrishNaturalists' Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.177 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:43:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

240 Ir. Nat. J. Vol. 20 No. 6 1981

APPENDIX A LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL DONATIONS, FROM THE COLLECTION OF

D. R. PACK BERESFORD, TO THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND, DUBLIN

N.M.I. Registration Number and full Catalogue Description 4. 1938 Collection of Spiders

? 70 jars.

28. 1938 Two glass jars of Irish woodlice. Records.

29. 1938 One glass jar of Irish Phalangids. Records.

30. 1938 One glass jar of woodlice and spiders from Algiers. 31. 1938 Three glass jars of less common species of Irish spiders. Records.

32. 1938 Four glass jars of common species of Irish spiders. Records.

64. 1942 Collection of material presented by D. J. Pack Beresford, the

property of his brother, the late Denis R. Pack Beresford. Including ten jars of Irish woodlice, 6 jars of foreign woodlice, 9 jars

miscellaneous and 4 tin boxes containing tubes of spiders and woodlice from the stomachs of (English) toads and frogs.

65. 1942 Annotated literature dealing with Irish and foreign woodlice,

spiders and harvestmen, etc. (given by H. D. Pack Beresford).

REMAINS OF GIANT IRISH DEER (MEGACEROS GIGANTEUS) FROM LARNE LOUGH CO ANTRIM

Peter Francis

Joint Conservation Laboratory, Queen s University/Ulster Museum, Belfast

Remains of the Giant Irish Deer Megaceros giganteus Blum, have previously been recorded at two localities in the Larne Lough area. A near complete Giant Irish Deer skeleton was found in lacustrine deposits at Ballymoney townland, Islandmagee (Fig. 1), (Belfast Naturalists' Field Club 1874, Mitchell and Parkes 1949). In 1959 the skull and antlers of one individual were found on the lough shore at Magheramorne and these fragments are now in the possession of the Ulster Museum (Cat. No. 1959 424). Unfortunately no information accompanies this material, but examination of the original clay matrix adhering to the antler fragments has yielded marine shells and foraminifera that would indicate an origin in Larne Lough itself.

During the latter part of 1977, Mr D. A. Loughridge of Portland Place, Magheramorne, unearthed several antler and skull fragments of Giant Irish Deer from the Quaternary marine clays on the southern shore of the spoil tip at Magheramorne quarry (Figs. 1 and 2). This tip extends over a large area of Larne Lough, and its weight has displaced (and is still actively displacing) the underlying marine muds upwards to sev I metres above the high water mark. These muds are best examined along the shoreline as vegetation obscures much of their exposure on

higher ground, and continuing marine erosion uncovers large quantities of sub-fossil material, mainly shells.

Initially one antler was found and discarded but subsequently a large fragment of a right antler was discovered nearby with a portion of the skull attached. This skull bears only the stump to the left and its brow tine, so it may be surmised ihat all of these cranial remains are from one individual.

Further search by Mr Loughridge and myself along the entire shore of the tip during October 1979, produced seventeen further cranialand post-cranial fragments. These

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.177 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:43:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ir. Nat. J. Vol. 20 No. 6 1981 241

include three separate left mandible fragments, representing a minimum of 3 individuals,

only one of which was complete and in situ but each with well preserved teeth; the

terminations of three tines, a distal portion of antler palmation, fragments of the second, third and fourth left ribs (not necessarily from the same animal) a left tibia, a left scapula, a

left ulnar fragment, and indeterminate portions of vertebrae and limb bones. From their size these specimens are all apparently adult. All of this post-cranial material was identified by

comparison with a complete (although composite) adult skeleton on permanent display in

the Ulster Museum. Remains of Giant Irish Deer were previously found by the author during 1968/9 along

the shore of land reclamation tips to the west of Curran Point, Lame (Fig. 1). The

significance of these specimens was not recognised at the time, but re-examination of this

material shows that a complete left cannon bone, two fragments of left humerus and a third

right rib were collected, all adult and all in a good state of preservation. They were found in

clay similar to that at Maghermorne and here also it would appear that a shelf of Quaternary

clays has been thrust upwards above high water through displacement by dumped material.

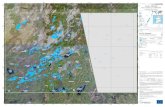

FIGURE 1 FIGURE 2

\Lough ^ \ ̂̂ ^^j5*Mandibte ^^QjVn

\ _|9

f IKm!^^-^ jnsittj |

Magheranrorrte+^b % X?r""" -T"V Rwginy of giartt frlsh Peer from Lame Lough

V I 1 I Locationof P^l Uplifted \ ) I I fincb ''" '"* Quaternaryclay

\> ( I ^| Reclaimed F:::.-::1 Main area of Ballycarry+ M V WM land k:"-::1 bone material

I i i i i i i y 10 12 3 4 5Kms. / J

Recent re-examination of the exposures at the Curran Point locality has failed to reveal

any further specimens so precise information as to the provenance of this material is

lacking. Of the Maghermorne remains, potentially the most informative is a single left

mandible found in situ, but the deformation which has accompanied the recent uplift of the

Quaternary clays, together with modern marine erosion, has so disrupted the succession that

no viable stratigraphy remains discernable. Apart from the availability of other organic material from the same stratigraphic horizon, it is difficult to derive further information as to

the provenance of the remains even from this in situ specimen.

The left mandible was found on the south-eastern shore of the quarry tip (see Fig. 2) at a point 880 cm. below HWM (60 cm vertically below high water level), partially embedded in the Quaternary clay. This jawbone is the best preserved specimen found to

date, lacking only the four incisor teeth, despite having been broken between the third and fourth cheek teeth into two discrete portions

? almost certainly as a result of deformation

during uplift. The enclosing plastic blue-grey clay was largely barren of visible shelly material but

contained many large peat blocks and black vegetational masses up to several metres across.

It was in clay between these peat blocks that the mandible was found. Praeger (1892)

suggested that these blue-grey clays are deep water (60 ft) marine, and it is most likely that

together with the animal remains the peat blocks were washed or rafted in from the nearby land. Their large size would suggest however that they were transported during periods of

exceptional flooding, and indeed the interposed clays show considerable turbidation. It is

difficult to envisage how objects as dense as the antlers of Megaceros could otherwise have

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.177 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:43:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

242 Ir. Nat. J. Vol. 20 No. 6 1981

been transported in the near still-water conditions then generally prevailing in Larne Lough.

Such periods of flooding would also account for the dispersal of the bones prior to burial since no other bones were found in situ within 10 metres radius of the mandible.

Unfortunately little further information is available on these clays. Exact age determinations have not as yet been undertaken, although it is almost certain that the Larne

Lough Giant Irish Deer correspond broadly with the Zone II (pollen) age obtained by Mitchell (1949) for the Ballymoney specimen. Available age determinations from elsewhere in Ireland would suggest that Megaceros was extant here only during this

relatively short period (corresponding to the Allerod interstadial, ca. 12,000-11,000 B.P.), (Gould 1974).

Of the material found to date the cranial remains are most easily compared withf

specimens elsewhere. The skull and antler fragment retains only the two scythe-shaped brow tines, but evidence of further tines remains on the right antler fragment, where they once joined the palmation. Of these, three projected anterio-dorsally (joining the palmation at approximately 350 mm, 650 mm, and 850 mm from the burr respectively) whilst the fourth projected posterially (at approximately 450 mm from the burr). A large portion of the antler tip is missing however, and undoubtedly further tines originally projected from this, but the remaining antler is approximately 826 mm long at its maximum extent, and up to

386 mm broad. The left antler has been broken close to the brow tine and only 184 mm is still attached to the skull. Of the skull, only the brain-case, forehead and left eye orbit remain, the nasal and palatal regions having been lost.

A variety of measurements have been made of the cranial dimensions of this specimen.

The parameters chosen correspond to those indicated in a system proposed by S. J. Gould

(1974), as this would appear to be the most reliable method by which inferences as to the

size, age etc. of a given Giant Irish Deer may be drawn from osteological data.

Of the parameters remaining on the Magheramorne specimen only the antler pedicel

height gives any direct indication as to the nature of the animal by offering a reliable estimate of the age of the individual. The height of 74 mm would suggest that the stag died in middle age when its antlers had grown to almost their maximum size (i.e. physical

maturity). This information allows other inferences to be drawn. A pedicel height of 74 mm

corresponds to a theoretical antler width of 380 mm, which is verified by an actual measurement of 386 mm. This in turn suggests a full antler length of 1140 mm (of which 826 mm remain) and a basal skull length of 490 mm.

Worthy of mention is the very small size of the brow tines (right 194 mm, left 177 mm), 42.8 mm and 65.5 mm respectively below the mean size quoted by Gould (1974) for mature Giant Irish Deer. This is largely related to their shape, the points being turned outwards at right angles with respect to the junction at the antler. The two tines are

also markedly assymmetrical (right 17 mm > left), a fact which is interrelated with the

assymmetry of the rose diameters.

The size of the complete mandible when compared to four similar specimens in the Ulster Museum collection (Cat. Nos. K3995, K3996, K3997, L5034) would suggest that it also belonged to a mature individual. With a maximum length of 408 mm (and a ramus 208 mm in height) the specimen was at least 12 mm longer than any of the Museum

specimens, but the difficulties of comparing a statistically small number of individuals should be borne in mind. These comparative examples were all male, as the associated

skulls bore antlers, and it is reasonable to assume that the Magheramorne mandible is male

also. It is not unlikely that this specimen belongs to the same individual as the skull and antlers originally found by Mr Loughridge, as it is his belief that these finds are all from the same general area.

The two further mandible fragments found loose on the shore are similar both in length and in circumference than the complete mandible. The precise lengths of these fragments are difficult to reconstruct as both are only small portions, but the circumference in each

case (from the base of the teeth) is only about 0.8 that of the complete mandible. The

remaining teeth are similar in size however (only the bone of the jaw is smaller), and show as much or even more wear than those of the complete specimen, so it is unlikely that they

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.177 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:43:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ir. Nat. J. Vol. 20 No. 6 1981 243

belonged to juvenile individuals. These mandibles therefore represent relatively small adult

males, or perhaps more probably adult females. Unfortunately no female specimens are

available in the Ulster Museum for closer comparison, but although seldom encountered in

the literature it must be assumed that females did exist.

Discussion

Several other points are worth noting in connection with the finds made so far. Firstly, no bones other than Giant Irish Deer were found at Magheramorne or the Curran. This would suggest that they greatly outnumbered the other cervids extant in this area at the time, or that the circumstances at death of certain Giant Irish Deer allowed only their remains to be

deposited in areas suitable for preservation. Also, there is no evidence to suggest damage to

the antlers during rutting or by resting on branches, as has been noticed on specimens from

elsewhere (Doughty 1966). From the number of finds made to date it would seem that remains of the Giant Irish

Deer must be fairly common within the Larne Lough clays, and now that their presence has

been noted it is to be hoped that further finds will come to light. The continuing erosion of the Quaternary clays bordering the spoil tip of Magheramorne quarry will certainly uncover

further material, and as this tip has not yet settled completely, fresh clay may also become

available for examination. Furthermore the great abundance of other organic remains within

the clays could provide a variety of information on the terrestrial and marine

palaeoenvironments of the time that is lacking at present. A prerequisite of any further study however would be the tabulation of a reliable stratigraphy, which present exposures are

unable to afford. Until such times, the resultant lack of precise provenance means that any

information which the Larne Lough localities can offer in relation to the Giant Irish Deer, must come from the bones themselves. The fact that many of these bones are loose beach finds is a disadvantage, but Magheramorne at least offers itself as a rich source of

post-cranial remains which have seldom been collected elsewhere.

Finally, all of the specimens collected to date are now in the possession of the author and would gladly be made available to any interested persons. The author would also be

pleased to receive any further information as to remains of Giant Irish Deer in East Antrim.

Acknowledgements

My thanks are due to Mr D. A. Loughridge, initially for having brought his finds to my attention, and subsequently for having sufficient enthusiasm to give frequent assistance in the field. I am also grateful to the staff of the Blue Circle Industries Limited at

Magheramorne, for having accommodated our many excursions onto the quarry tip, and Mr

P. S. Doughty, Keeper of Geology, Ulster Museum, for his assistance in examining

comparative material and in preparing this manuscript.

References

Doughty, P. S. (1966) Giant Irish Deer remains from Lough Neagh. Ir. Nat. J. 15: 187.

Belfast Naturalists' Field Club (1874) Guide to Belfast and its Adjacent Counties. Belfast, Marcus

Ward, 327pp. Gould, S. J. (1974) The Origin and Function of 'Bizarre' Structures: Antler Size and Skull Size in the

Trish Elk'. Evolution 28: 191-220.

Mitchell, G. F. and Parkes, H. M. (1949) The Giant Deer in Ireland. Proc. R. Ir.Acad. 52B: 291-314.

Praeger, R. L. (1892) Report on the Estuarine Clays of the North-East of Ireland. Proc. R. Ir. Acad. (3)2: 212-289.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.177 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:43:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions