REDD+ hits the ground - pubs.iied.orgpubs.iied.org/pdfs/16614IIED.pdf · REDD+ hits the ground Tom...

Transcript of REDD+ hits the ground - pubs.iied.orgpubs.iied.org/pdfs/16614IIED.pdf · REDD+ hits the ground Tom...

REDD+ hits the ground

Tom Blomley, Karen Edwards, Stephano Kingazi, Kahana Lukumbuzya, Merja Mäkelä and Lauri Vesa

Lessons learned from Tanzania’s REDD+ pilot projects

IIED Natural Resource Issues Series Editor: James Mayers

REDD+ hits the groundLessons learned from Tanzania’s REDD+ pilot projects

Tom Blomley, Karen Edwards, Stephano Kingazi, Kahana Lukumbuzya, Merja Mäkelä and Lauri Vesa

First published by the International Institute for Environment and Development (UK) in 2016 Copyright © International Institute for Environment and DevelopmentAll rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-78431-320-3 ISSN: 1605-1017

To contact the authors please write to: Tom Blomley, [email protected]

For information on the Natural Resource Issues series please see inside the back cover of this book. For a full list of publications please contact:International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED)80-86 Grays Inn Road, London WC1X 8NH, United [email protected]/pubs

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

@iiedwww.facebook.com/theIIEDDownload more publications at www.iied.org/pubs

Citation: Blomley, T, Edwards, K, Kingazi, S, Lukumbuzya, K, Mäkelä, M and Vesa, L (2016) REDD+ hits the ground: Lessons learned from Tanzania’s REDD+ pilot projects. Natural Resource Issues No. 32. IIED, London.

Design by: Eileen Higgins, email: [email protected]

Cover photo: Community member undertaking assessment of tree and carbon stocks in her village forest reserve, Kilwa District, Tanzania. © Anne-Marie Gregory/MCDI

Printed by Full Spectrum Print Media, UK on 100% recycled paper using vegetable oil based ink.

i

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

i

Contents

AbstractAcknowledgementsAcronyms and abbreviationsExecutive summary

1 Introduction and background

2 Methodology and approach

3. The feasibility and viability of REDD+ in Tanzania

4. Identifying and addressing drivers of deforestation and forest degradation

5. Adapting participatory forest management to a REDD+ context

6. Benefit sharing

7. Consultation, stakeholder engagement and consent

8. Measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification

9. Getting projects to market

10. Looking back down the road to REDD+

References

iiiivv

vii

1

7

8

11

14

22

28

32

36

39

42

ii

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

ii

List of TablesTable 1: Overview of completed REDD+ pilots in TanzaniaTable 2: Benefit sharing arrangements under REDD+ pilot projectsTable 3: Status of four REDD+ pilot projects with regard to certification

List of BoxesBox 1: TFCG / MJUMITA model for benefit sharingBox 2: Summary of key practical lessons learned from the pilot projects in moving towards FPIC for REDD+

List of FiguresFigure 1: Map of REDD+ pilot projects in TanzaniaFigure 2: Comparison of above-ground biomass models applied in the REDD+ projects

32437

2530

533

iii

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

iii

Abstract

In 2009, the Tanzanian government, together with the Embassy of Norway, launched a series of pilot projects with the goal of testing approaches to reducing deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). These projects experimented with a range of different approaches to protecting forests and reducing carbon emissions, while supporting livelihoods and local economic development. In this report, we review the experiences and lessons learned from these pilot projects. We find that Tanzania’s unique legal and institutional framework for decentralised forest management has provided new opportunities to test how communities can be engaged in REDD+, but that new challenges have emerged due to the trade-offs between setting aside forest areas for long-term protection and short-term needs for agricultural expansion.

The technical challenges of establishing robust measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification systems have been a major hurdle for most projects, which in turn have delayed the development of approved project design documents. Other challenges have been low carbon stocks within Tanzania’s dry miombo forests and the high costs of implementing projects in remote areas of the country, which coupled with a weakening market for carbon, have undermined the economic viability of voluntary carbon projects. Limited interest from buyers in forest carbon has also meant that no projects have to date been able to sell carbon on the voluntary market.

However, some of the new opportunities that have emerged include benefit sharing approaches, designed and endorsed by the final recipients. These offer the most promising models for ensuring continued support for forest protection and improved management. Individual payment approaches, while costly to establish and maintain, have been found to minimise risks of elite capture and ensure widespread support for REDD+ across a given community. In addition, the inclusion of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) within project certification schemes has strengthened engagement between project proponents and participating communities, when compared with more mainstream approaches to community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) in Tanzania.

iv

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

iv

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank a number of individuals and institutions in Tanzania and elsewhere who have made this review possible. Firstly, we thank Søren Dalsgaard, Berit Tvete and Yassin Mkizu of the Norwegian Embassy in Tanzania who invited us to participate in the evaluations and review of lessons learned of REDD+ pilot projects between December 2014 and June 2015. Secondly, we extend our thanks to the individuals working within the implementing organisations who gave their time and inputs openly and freely, culminating in a two-day workshop in Dar es Salaam in May 2015 where findings were synthesised. Thirdly, we thank all the community members and partner organisations that supported our field visits across mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar, and who patiently and openly answered our questions and shared their views. Finally, we thank IIED – James Mayers for reviewing the text and welcoming the report into the Natural Resource Issues series, and Kate Lewis, Nicole Kenton and Khanh Tran-Thanh for their help in its production.

This report was funded by UK aid from the UK government, though the views expressed do not necessarily represent those of the UK government. The views expressed herein, and any remaining errors, remain the responsibility of the authors.

v

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

v

Acronyms and abbreviations

AWF African Wildlife FoundationBAU Business as usualCARE CARE InternationalCBFM Community-based forest managementCBNRM Community-based natural resource managementCCB Climate, community and biodiversity (Standards)CCBA Climate, Community and Biodiversity AllianceCFMA Community forest management areaCIFOR Centre for International Forestry Research CO2 Carbon dioxideCoFMA Community forest management associationD&D Deforestation and forest degradationFAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United NationsFPIC Free prior and informed consentFSC Forest Stewardship CouncilGIS Geographical information systemHIMA Hifadhi ya Misitu ya Asili (Protecting natural forests)ICT Information communication technologyIUCN International Union for Conservation of NatureJFM Joint forest managementJGI Jane Goodall InstituteJMA Joint management agreementJUHIBEKO Jumuiya ya Hifadhi ya Mazingira Tarafa za Bereko na Kolo (Union for protection of environment in Bereko and Kolo)JUMIJAZA Jumuiya ya Uhifadhi wa Misitu ya Jamii Zanzibar (Union of community forest associations, Zanzibar)JUWAMMA Jumuiya ya Watunzaji wa Msitu wa Masito (Network for Forest Protection of Masito)LULC Land use and land coverMCDI Mpingo Conservation and Development InitiativeMJUMITA Tanzania Community Forest Conservation NetworkMNRT Ministry of Natural Resources and TourismMRV Measurement, reporting and verificationMtCO2e Million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalentNCMC National Carbon Monitoring CentreNGO Non-governmental organisationNOK Norwegian KroneOECD/DAC Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development / Development Assistance CommitteePDD Project design documentPFM Participatory forest managementREDD+ Reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation

vi

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

vi

RNE Royal Norwegian EmbassyRS Remote sensingSCC Shehia Conservation Committee (Zanzibar)tCO2e Tonnes of CO2 equivalentTFCG Tanzania Forest Conservation GroupTNRF Tanzania Natural Resource ForumTZS Tanzania shillingUNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate ChangeUN-PEI United Nations Poverty and Environment InitiativeURT United Republic of Tanzania US$ United States dollarVCS Verified Carbon StandardVER Verified emission reductionVLFR Village land forest reserveVLUP Village land use planVNRC Village natural resource committeeWCS Wildlife Conservation SocietyWWF Worldwide Fund for Nature

vii

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

vii

Executive summary

While much has been written about REDD+ from a theoretical perspective, and much of it largely critical, little work has been done on analysing and documenting practical implementation of REDD+ activities on the ground. This report aims to fill this apparent gap by offering emerging lessons, experiences and insights gained from the implementation of REDD+ pilot projects across Tanzania between 2009 and 2015.

The pilot projects were designed to test local approaches to implementing REDD+ across a range of different social, institutional, tenure and ecological conditions. Funding for the REDD+ projects was provided by the government of Norway through the Royal Norwegian Embassy. Much of the material for this review was gathered from external evaluations of individual pilot projects that we undertook on behalf of the Norwegian government between December 2014 and May 2015. We also organised a two-day workshop in Dar es Salaam at which implementing organisations were encouraged to identify key lessons learned. We present these lessons in eight thematic areas, as summarised below and as presented as chapters in the paper:

The feasibility and viability of REDD+ in Tanzania When compared with other tropical countries with high carbon stocks, Tanzania presents many challenges from a REDD+ perspective in terms of its overall viability to support REDD+. Low rainfall across much of the country means that forests are generally relatively low in carbon. Drivers of deforestation and forest degradation are multiple, interlinked, locally-derived and inextricably linked to the actions of millions of rural land and forest users. Developing cost-effective strategies that can address such drivers at scale is immensely challenging. The size of the country, coupled with poor accessibility, means that the costs of establishing and running field-based activities are high. Compounding these challenges are the low prices and weak demand for carbon offsets on the global voluntary market. Despite these evident challenges, Tanzania has a unique legal framework, which presents unique opportunities for decentralised decision-making and locally-driven natural resource management. A key aspect of this enabling legal framework is Tanzania’s participatory forest management programme.

Identifying and addressing drivers of deforestation and forest degradationThe main drivers of forest degradation, as identified by pilot projects, are the growing energy needs of an expanding population (principally charcoal) and the expansion of small-scale agriculture into non-farmed areas. At the local level, drivers are complex, multi-sectoral, and often interlinked. After detailed studies on local drivers of deforestation and forest degradation, pilot projects experimented and tested a range of different tools and approaches for addressing the drivers

viii

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

viii

with varying degrees of success, effectiveness and efficiency. Identifying the models and approaches that can be taken to scale is a crucial part of achieving emission reductions and other REDD+ results under a national or jurisdictional approach. This is an area where projects have been less successful, as many activities being implemented by projects require significant levels of staffing and financial support at a very local level. Pooling resources and creating partnerships with non-forestry organisations and institutions are approaches to address the agriculture and energy drivers in a more strategic and cost-efficient way and across a wider area. With regard to the different interventions practised by different projects, participatory forest management, community-based fire management and conservation agriculture appear to be the most effective approaches for addressing deforestation drivers in the Tanzanian context.

Adapting participatory forest management to a REDD+ context REDD+ has created funding and implementation opportunities for scaling up participatory forest management (PFM) across different parts of the country. Many of the pilot projects used PFM as a key strategy to devolve control over forest resources to local communities, with 491,000 hectares (ha) of woodlands and forest under some form of local management as a direct result of pilot project actions. The use of PFM within the context of REDD+ has sparked a healthy debate regarding the goals, objectives and implementation of PFM within Tanzania. A key lesson is that REDD+, with its externally defined objectives of reducing carbon emissions and conserving carbon stocks, may distort local incentives for forest management by protecting larger areas of forest than would otherwise have been the case. REDD+ often conflicts with local demands for expanding agricultural production and such trade-offs need to be negotiated in a participatory and inclusive manner. A second key finding is that community-based forest management (CBFM), as practiced across Tanzania over the past two decades, may be resulting in high levels of leakage. Previous CBFM efforts have tended to be strongly focused on the management of specific areas of forest within village lands, with little attention to the management of trees on village lands outside community-protected areas. REDD+ projects have also generated valuable lessons with regard to the formation of inter-village aggregation entities that are able to present larger, economically-viable volumes of carbon to the international voluntary carbon market than would be possible from individual, dispersed and relatively small forest areas under PFM at individual village level.

Benefit sharingBenefit sharing arrangements in the context of natural resource management is a contentious issue that has stoked controversy within the Tanzanian PFM debate. Pilot projects, by including ‘front-loaded’ payments in their budgets, were able to experiment with benefit sharing models at individual, group and community levels. Individual payments, while accounting for high transaction costs, minimised risks of elite capture and were instrumental in creating high levels of awareness and support for avoided deforestation measures at the community level.

ix

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

ix

Consultation, stakeholder engagement and consentPilot projects have experimented over a continuum of approaches and although only one project explicitly included free prior and informed consent (FPIC) in its original design, at least three others, through an adaptive learning process, integrated FPIC practice into their implementation. The inclusion of a requirement to respect the right to FPIC as part of the climate, community and biodiversity (CCB) validation for REDD+ appears to have stimulated and incentivised more conscious practice and the facilitation of quality participation and community decision-making to achieve consent for REDD+ interventions in Tanzania, although initially perceived by many as only relevant to indigenous peoples. Pragmatically, it was recognised by most of the pilot project NGOs that engaging local people in project decisions is critical to ensure effective project implementation. Obtaining consent within the context of a REDD+ pilot project generated important benefits, but also resulted in delays and additional up-front costs.

Measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification REDD+ pilots have experimented with a variety of approaches to measuring, monitoring, reporting and verification, all of them combining highly technical, remote sensing (RS) approaches with community-based forest carbon monitoring models. Piloting of participatory forest carbon monitoring in the context of REDD+ pilot projects has demonstrated that communities are capable of undertaking complex and technically demanding MRV tasks when sufficient training and incentives are applied. Due to the dependence on contracted external expertise, challenges with untested technology, the absence of national standards and a body for guiding MRV and hosting collected carbon data, some REDD+ pilot projects have not achieved their objectives of building a sustainable MRV system. No project has been able to feed data to national level forest carbon monitoring because the National Carbon Monitoring Centre (NCMC) is yet to become operational. The creation of different MRV approaches (and in particular forest stratification and data analysis protocols) has meant that comparison of datasets and results between projects is methodologically challenging.

Getting projects to marketGetting REDD+ projects proved much more complex than originally anticipated. This was caused by a combination of factors, including a lack of internal technical capacity coupled with poor support from specialist service providers. However, many projects simply under-estimated the time, effort and cost of developing a comprehensive project design document of a sufficient quality to be validated externally. As a result of these problems, many projects missed their targets of producing project design documents (PDDs) by the end of their funding term. Problems have been compounded by the realities of getting validated projects to market – due to falling carbon prices as well as limited demand. These realities threaten both the viability and sustainability of project-based approaches in Tanzania.

x

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

x

Looking back down the road to REDD+Many fears were being expressed both within Tanzania and internationally regarding REDD+ when the pilot projects were launched. These fears related to resource grabs, recentralisation of hard-won forest tenure rights, and a return to ‘fortress conservation’. Our findings do not provide evidence to support these fears, in large part because of the widespread market failures associated with the REDD+ voluntary carbon markets. While far from perfect, many of the pilot projects went beyond previous approaches to secure consultation, to avoid elite capture of project benefits, and to strengthen forest management rights through community-based forest management.

1

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

1Introduction and background

While the discourse surrounding REDD+ to date has been vibrant and frequently critical, there has been limited discussion around constructive approaches, grounded in field implementation, on how REDD+ can work in the complexities of the African context. This paper aims to address this gap by offering lessons, experiences and insights from Tanzania –a country with a strongly devolved legal framework to governance and natural resource management – on how REDD+ can work on the ground.

Tanzania, like many developing countries, has been engaged in developing national capacity and systems for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) since around 2009. With support from the government of Norway as well as other international agencies, such as the UN-REDD programme, the government of Tanzania has been directing activities to two levels. At national level, a series of activities has been implemented to prepare for results-based financing. This includes the establishment of a National Carbon Monitoring Centre at the Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA) in Morogoro, the development of environmental and social safeguards, the strengthening of inter-governmental coordination, as well as the setting up training and awareness-raising programmes at many levels.

At sub-national level and in parallel to these national efforts, the Tanzanian government, with support from the Norwegian government, has supported NGO pilot projects across the country. These pilot projects were designed as a ‘testing ground’ for REDD+ in Tanzania, with the expectation that early, field-tested results and lessons would feed into and inform the evolving national REDD+ readiness process. Pilot projects were expected to contribute to one or more of the following four outcome areas:

n Building local REDD+ readiness: The aim was to build REDD+ readiness processes, including the establishment of the necessary local institutional arrangements for carbon stock monitoring, accounting, marketing and financing.

n Policy testing: Combined with research, communications and advocacy interventions, the pilot projects were set up to allow the testing of different REDD+ policies with a view to informing future policy development at a national level. These included benefit sharing, participatory monitoring, local governance and ways to address the deforestation and forest degradation (D&D) drivers.

n Supporting broad stakeholder involvement: By ensuring a wide geographic spread of projects across the country, it was envisaged that pilot projects would help to ensure sufficient diversity in terms of stakeholder perceptions, experience and involvement during the REDD+ readiness phase.

n Delivering REDD+ results: In addition to supporting REDD+ readiness, projects were also expected to deliver REDD-related results, such as measurable

2

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

improvements in forest condition, emission reductions from reduced deforestation, as well as social and environmental benefits from improved forest management. Projects were encouraged to include ‘front-loaded’ payments within their budgets to test payment and benefit sharing arrangements in the expectation of making longer-term carbon sales through the voluntary carbon market.

In February 2009, the Royal Norwegian Embassy (RNE) in Tanzania and the National REDD+ Task Force launched the pilot project process. More than 40 concept papers were received in response to a call for applications and out of these, a total of nine were selected for financial support. By the end of 2014, seven REDD+ pilot projects were completed according to plans.1 One of the seven completed pilot projects, implemented by the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF), was fundamentally different from others as it mostly aimed at creating detailed carbon baseline data and building capacity of Tanzanian professionals in MRV. The seven completed projects designed to deliver REDD+ results are summarised below in Table 1.

1. Two pilot projects, implemented by the Wildlife Conservation Society of Tanzania and the Tanzania Traditional Energy Development Organisation were discontinued due to financial reporting and audit concerns. These two projects are not included in the analysis.

3

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

Organisation and project title

Project description Funding and timeframe

African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) Advancing REDD in the Kolo Hills Forests

Purpose: Preparing local communities to participate in REDD as an incentive for long-term conservation.Where: Covers 18 villages and 71,632 ha of mixed land uses including 20,146 ha of forest.Actions: Assessing carbon and other benefits; enhancing REDD understanding; improving land and forest management; developing benefit sharing mechanisms (including trial payments); supporting livelihoods alternatives. Credits being validated by Plan Vivo.Outcomes: 12,832 ha of forests under PFM; 26,153 tCO2e / annum reduced emissions (not verified).

NOK 17.71 m 5 years Jan 2010 – Dec 2014

The Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) Building REDD readiness in the Masito Ugalla Ecosystem Pilot Area

Purpose: Building awareness and enhancing capacity and governance for local communities and government to administer and benefit from REDD in high biodiversity forests.Where: Covers 90,989 ha of miombo woodland under varied ownership between 13 villages. Actions: Facilitating establishment of: inter-village CBOs to manage forests, replicable and scalable remote sensing method, community and CBO capacity to monitor carbon stocks, and community mechanism for equitably sharing carbon revenues; trial payments made.Outcomes: Conservation of 90,989 ha forest, anticipated (but not verified) 55,000 MtCO2e emission reductions from avoided deforestation.

NOK 19.32 m 3.5 years Jan 2010 – June 2013

Mpingo Conservation and Development Initiative (MCDI) Combining REDD, PFM and FSC Certification in Southeastern Tanzania

Purpose: Using financial flows from REDD to expand PFM and Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) certification of sustainable timber harvesting in village land forest reserves.Where: Southern-coastal Tanzania. 10 villages with 17,829 peopleActions: MCDI used REDD revenue to off-set start-up costs for PFM and FSC certification (combining REDD, PFM and FSC); Community based fire management.Outcomes: 96,112 ha under CBFM; 27,600 MtCO2e reduced emissions (not verified).

NOK 13.64 m 5 years Jan 2010 – Dec 2014

Tanzania Forest Conservation Group (TFCG) and Community Forest Conservation Network of Tanzania (MJUMITA) Making REDD Work for Communities and Forest Conservation in Tanzania

Purpose: Pro-poor approach to REDD, generating equitable financial incentives for communities sustainably managing or conserving Tanzanian forests. Performance-based. Communities directly access REDD finance. Credits validated by VCS and CCB.Where: 27 villages (49,025 people) in two districts. High biodiversity hotspots. Actions: Assisting communities to market emission reductions generated through interventions that aim to address the main deforestation drivers including CBFM, improved agriculture, improved forest governance and land use planning; national and international advocacy on REDD policy; performance-based payments made.Outcomes: 152,000 ha of miombo / coastal forest conserved; 39,896 t CO2e reduced emissions verified in Lindi from 2012 to 2013.

NOK 41.40 m 5 years Sep 2009 – Dec 2014

Table 1. Overview of completed REDD+ pilots in Tanzania

4

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

CARE Tanzania Hifadhi ya Misitu ya Asili (HIMA) / Piloting REDD in Zanzibar through Community Forest Management

Purpose: Ensuring REDD+ benefits contribute to reducing poverty and enhancing gender equality.Where: 45 Shehias, (113,845 people) on Zanzibar and Pemba islands. Actions: Promotes community forest management through: Addressing drivers; Improving governance, including equitable benefit sharing; Ensuring poor benefit and are not further disadvantaged; Controlling leakage, eg domestic woodlots and income generating alternatives; Mainstreaming gender.Outcomes: 82,754 ha of forested land protected by community forest management areas (CFMAs); 581,252 t CO2e reduced emissions (not yet verified)

NOK 38.77 m 4.5 years Apr 2010 – Dec 2014

Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) REDD Readiness in Southwest Tanzania

Purpose: Develop capacity and knowledge to participate in REDD, while establishing sustainable alternatives. Where: In and around protected areas (PAs) in four forests in Southern Highlands (52,680 ha). 40 villages (70,000 people).Actions: Baseline study, Provide methods for estimating degradation, deforestation, carbon sequestration, emissions, leakage; Provide carbon data; Demonstrate appropriate tools for implementing and monitoring REDD; Estimate expected emission reductions levels; Provide economic incentives (and address drivers), including benefit sharing, environmental education, and alternative forest resource provision.Outcomes: 50,000 people reached with environmental education; 250 ha woodlots established. No data on emission reductions.

NOK 9.3 m 4 years July 2010 – June 2014

Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) Tanzania Enhancing Tanzanian capacity to deliver short and long-term data on forest carbon stocks across country

Purpose: Contributing core data to the Tanzanian national MRV system that forms a part of the comprehensive forest carbon monitoring system for the country, and build capacity for sustainability in the future.Where: Across seven major vegetation types in seven regions.Actions: Baseline carbon plots, Hemispherical photographic survey, Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) technology further tested, soil carbon survey, future scenarios for changes in carbon stock, capacity building. Outcomes: 522 soil samples collected and analysed; 128 one-ha permanent carbon monitoring plots established and assessed

NOK 13.9 m 4.3 years Jan 2011 – March 2015

5

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

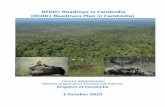

Tanzania is a diverse country, with a range of ecological conditions and forest types – including highland montane forests, dryland acacia and miombo woodlands as well as coastal forests. Pilot projects were strategically selected to ensure a wide geographic and coverage of the country to include these diverse conditions (see Figure 1).

Tabora

Dodoma

Kigoma

Kilwa Kivinje

KasulaShinyanga

Arusha

MbeyaSumbawangaSumbawanga

Kondoa

Iringa

Morogoro

Lindi

U N I T E DR E P U B L I C

O F T A N Z A N I A

K E N Y ALake

LakeVictoria

Kivu

LakeTanganyika

LakeNyasa

L. Eyasi

L. Natron

L. Manyara

Dar-es-SalaamDar-es-Salaam

Tanga

N

0 200miles

ShanganiShangani

TFCGTFCG

CARE

CARE

MCDI

CARE

CARE

KilwaKivinjeKilwaKivinje

AWFAWF

JGI

KilosaKilosa

TFCGTFCG

WCS

WCSWCS

WCS

REDD Pilot Sites

major towns

rivers

Figure 1. Map of REDD+ pilot projects in Tanzania

Source: WCS.

6

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

When the REDD+ pilot projects were launched in 2009, REDD+ as a concept was largely unknown in Tanzania. Awareness and understanding of REDD+ within the government and civil society was extremely limited. Even among international conservation NGOs, capacity was low. No national REDD+ strategy had been developed, and at international level, the now-familiar discussions on monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV), reference levels, carbon baselines, and accounting and safeguards had yet to take place. At the international level, fears were being expressed that REDD+ would inevitably lead to a ‘resource grab’, whereby powerful interests would capture the rights to forest areas with a view to generating carbon credits, thereby displacing traditional resident forest users (Phelps et al. 2010).

We were commissioned by the Norwegian Embassy in Tanzania to undertake external final evaluations of six of the seven pilot projects between January and May 2015 (NIRAS 2015a-f). The JGI project was reviewed in 2014 separately because it closed in 2013. Given the strong focus on learning, policy testing innovation and experimentation that was implicit within the pilot project approach, the RNE also commissioned a study on lessons learned from the seven pilot projects (NIRAS 2015g). The findings we present in this publication draw extensively on these six evaluations and one overall synthesis report. Chapter 4 of this report draws heavily on an article we submitted for publication in the Journal of East African Studies.2

2. Blomley et al. (in preparation).

7

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

2Methodology and approach

Given the explicit focus of the pilot projects with regard to learning and informing, many of the implementing agencies have already undertaken internal reviews of lessons learned during the course of implementation.3 Cross-project exchanges of lessons learned have also been facilitated to a lesser extent by the Tanzania Natural Resources Forum (TNRF) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), although these were undertaken when the projects were in their early stages.4 In total, 12 publications have been produced that seek to identify and describe lessons learned from Tanzania’s experiences in implementing REDD+. Our review of lessons learned differs from previous ones conducted in three key ways:n It took place after all projects had been completed.n It was written by an independent team with no direct role in implementation.n It places the Tanzanian experiences within a wider, global context of emerging

experiences from other sub-national implementation initiatives.

As such, we provide lessons that try to answer two key questions:n What unique aspects of Tanzania’s political, legal or ecological situation

provide valuable lessons / experiences that are of use to both Tanzanian and international audiences engaged in REDD+?

n What unique aspects of the Tanzanian pilot project experience provide useful lessons and experiences to other REDD+ practitioners working on similar initiatives but in different countries?

The main methods we used in this review include:n Reviewing and synthesising the findings and conclusions of the final review of

pilot projects.n Reviewing and synthesising literature and documentation already produced by

pilot projects.n Reviewing global literature and lessons relating to emerging experiences with

REDD+ pilot projects and the evolution of REDD+ more generally.n A two-day workshop with participating NGOs to identify and explore lessons

learned, held in Dar es Salaam in March 2015.

This publication is written primarily with practitioners in mind – both in Tanzania and internationally – in the hope that some of the experiences and lessons identified here can be adopted by others.

3. See for example: Jarrah 2014. 4. See for example: TNRF 2011.

8

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

3The feasibility and viability of REDD+ in Tanzania

Carbon stocks and deforestation driversWoodlands occupy 44 million ha (or 91 per cent) of the total forest area of Tanzania (MNRT 2014). Despite this relatively high level of coverage, biomass is relatively low (estimated to be around 55.1 m3/ ha). The associated carbon stocks in Tanzanian woodlands are estimated to be 17.5 tC/ha comparing unfavourably with more well-stocked forests in rainforest nations such as Indonesia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Brazil, where carbon stocks are generally in the region of 120-140 tC/ha (FAO 2010). In Asia and Latin America, deforestation is driven largely by large-scale, commercial food, oil and fibre production (such as beef, soya, plantation forestry, rubber and palm oil). In Africa, however (and in particular sub-Saharan Africa), forest degradation predominates, driven by more locally-derived factors such as fuelwood collection, subsistence agriculture, charcoal production and livestock grazing (Kissinger et al. 2012; Streck and Zurek 2013). This results from the actions of numerous individuals harvesting forests for timber, charcoal and firewood, as well as from slash-and-burn agriculture, which takes place in forested landscapes. Measures to address forest loss must therefore work at a sufficiently local level to engage with rural farmers and forest users.

Implementing REDD+ in Tanzania: costly and slowIn countries such as Tanzania, the costs of working at community level in remote, poor and inaccessible parts of the country are high. Approved methodologies under VCS for measuring and reporting on forest degradation, caused by the actions outlined above, are currently unavailable or prohibitively expensive and as such, more imprecise tools are needed to assess forest loss through deforestation. The MCDI project identified fire as being the biggest driver – accounting for the greatest levels of forest degradation. Unable to find any suitable methodology that could measure and report on forest degradation through fire, the project produced a new methodology under VCS, which has recently been approved (VCS 2015). Again, this has both cost and time implications, and without the support of a flexible funding agency, this would have been well beyond the financial means of a national Tanzanian NGO.

With the prevailing low carbon prices on the international voluntary market (currently around US$3-5/tonne), the overall viability of market-based approaches is questionable, given the high transaction, opportunity and institutional costs required to implement REDD+ activities in Tanzania. The TFCG/MJUMITA project calculated that they would need to sell carbon above a threshold price of US$7/ tCO2e if they were to pay communities at a minimum rate of US$3.25/ tCO2e, as well as maintain (and expand) current levels of support to communities (MJUMITA 2014).

9

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

As seen in other sub-Saharan countries, forest loss in Tanzania is largely caused by forest degradation and not deforestation (we define the latter as wholesale clearance of forest and conversion to other uses). The agents of forest degradation are generally small-scale farmers expanding agricultural production through extensive systems of slash-and-burn agriculture. As such, any measure to address these drivers must work at this level, by empowering those local level actors to manage forests more effectively while improving local level agricultural practices. Forty-six per cent (21.9 million ha) of all forests and woodlands in Tanzania are found on village land5 and are therefore under the authority of elected village governments (MNRT 2014). The Forest Act (2002), drawing in turn on the Local Government Act (1982) and Village Land Act (1999), recognises this and provides village governments with the mandate and necessary incentives to claim and manage forests on village land. The availability of these enabling laws means that transaction costs for REDD+ projects in Tanzania are arguably lower than in other similar sub-Saharan countries with a less favourable legal environment.

The importance of site selection and ‘knowing your drivers’Tanzania is a diverse country and covers a range of agro-climatic conditions, forest types and population densities. As such, deforestation and forest degradation drivers vary significantly across the country in both their nature and their intensity. Given this high variability, different sites have very different potential (and viability) for implementing REDD+ interventions – something that was clearly demonstrated by different pilot projects. Furthermore, initial assessments of deforestation drivers were often changed following more detailed studies undertaken during project implementation.

TFCG/MJUMITA, with support from Forest Trends, had the most thorough site selection process, which used both pre-screening as well as selection criteria to identify those areas with the highest potential for generating the greatest impacts (Forest Trends 2010). Criteria included factors such as area of unreserved forest (suitable for inclusion with village-managed forest reserves); biodiversity; carbon density; leakage risks; population density (ratio of community size to available forest area); deforestation levels and opportunity cost. Despite this very thorough process, new threats emerged during the project in one of the two project sites – namely an influx of migrants from nearby areas, who are clearing land and planting tobacco, something that was unforeseen when the initial site selection was taking place.

MCDI initially assumed that the biggest deforestation driver in their project area was charcoal production (and therefore had designed a project based around sustainable charcoal production). However, after careful study, it became clear that at current levels, commercial charcoal production was a minor factor – and, as mentioned earlier, fire was in fact the biggest driver of forest change in Kilwa

5. Village land is a category of rural land that is administered by village governments.

10

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

district. As such, a fundamentally different approach was needed to address REDD+ (Ball and Makala 2014). AWF initially selected a government forest reserve in which to develop a REDD+ project, given its high value as a water catchment area for a downstream national park (Tarangire). However, when it became apparent that current methodologies of measuring and accounting for forest degradation within protected areas were complex and largely untested, it became necessary to expand the project area and approach to include reforestation and support to forest protection within community-managed forests.

The JGI project identified a large area of contiguous miombo woodland, shared between 15 villages. However, disagreements over tenure of the forest (specifically whether it would be managed by district or village governments) resulted in long delays, disputes and ultimately the project being delayed well beyond its funding period.

Summary of key messages

n Tanzania presents many challenges from a REDD+ perspective in terms of its relatively low forest carbon stocks, complex and locally-derived drivers of forest degradation, its size and accessibility.

n Low prices and weak demand for carbon offsets threatens the viability of voluntary market carbon projects.

n Despite these challenges, Tanzania has a unique legal framework, which provides for decentralised decision-making and management of natural resources, and ensures that local actions can be taken effectively.

n High levels of variability across the country in terms of local deforestation rates, deforestation drivers and tenure regimes means that project site selection is a key factor in determining the viability of local actions.

11

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

4Identifying and addressing drivers of deforestation and forest degradation

Deforestation drivers – in the global and Tanzanian contextA comparative study conducted in 46 countries showed that commercial agriculture is the most important direct driver of deforestation globally, followed by subsistence agriculture, while timber extraction and logging drives most forest degradation (Verchot et al. 2014). Other important drivers of degradation are fuelwood collection and charcoal production, uncontrolled fire and livestock grazing. The most important underlying or indirect drivers are economic growth based on the export of primary commodities and an increasing demand for timber and agricultural products in a globalising economy (Kissinger et al. 2012). In REDD+ readiness plans, many countries identify weak forest sector governance and institutions, lack of cross-sectoral coordination and illegal activity (related to weak enforcement) as critical, indirect drivers. Population growth, poverty and insecure tenure are also cited. The Tanzanian national REDD+ strategy identifies charcoal and firewood harvesting, illegal logging, forest fires and agricultural expansion as the top deforestation drivers; and weak law enforcement, poor forest governance, conflicting policies and market failures as indirect drivers (URT 2013).

A study by CIFOR in 2014 in 48 REDD+ countries on monitoring of direct and enabling interventions to address the D&D (Salvini et al. 2014) found that the most commonly identified direct interventions are sustainable forest management, fuelwood efficiency / cook stoves, agroforestry, protected areas strategies and afforestation or reforestation. Also agricultural intensification, permanent agriculture, plantations establishment and management and livestock rangeland management are widespread interventions. Concerning enabling interventions, the most common are stakeholder involvement (including CBFM), tenure and rights regularisation and policy and governance reform. The study goes on to state that many of the REDD+ activities identified are likely to have a relatively low carbon impact per unit area, but can have significant cumulative effects over large areas. Usually a combination of interventions is needed to address the drivers: for instance, agricultural intensification should be combined with zoning, protected areas or rehabilitation of degraded lands to prevent further forest clearing, and this should be backed up by support at policy levels (Skutsch and McCall 2010).

Addressing deforestation and forest degradation in TanzaniaCurrent estimates show that current harvesting in Tanzania exceeds the annual allowable cut by 7.6 million m3. Increasing woody biomass in plantations, the promotion of agroforestry practices and reducing slash-and-burn agriculture (through conservation agriculture, for example) offer solutions to these trends. This must be implemented together with measures to reduce consumption – such as the promotion of improved stoves, improved efficiency in processing and use

12

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

of waste material, as well as a shift in energy patterns. Enhancement of carbon stocks has been a common aspect of many pilot projects: CARE International and WCS supported both planting of fast growing exotic species for fuelwood and pole production, while AWF promoted production through boundary planting agroforestry. Regeneration of mangroves through planting was supported in Zanzibar, which is an acceptable activity under REDD+. Conservation agriculture was promoted in a number of projects including JGI, TFCG/MJUMITA and CARE International. Most pilot projects successfully supported the building of local organisations and institutions to plan and manage the use of village land and community forests as an enabling intervention. This had a significant impact on improving security of land tenure and control over the common property forests. All projects worked on PFM apart from WCS.

At the local level, drivers are complex, multi-sectoral and interlinked. The most important drivers identified by the pilot projects include agriculture (both slash-and-burn and the opening of new permanent agricultural areas), commercial woodfuel (charcoal and firewood) harvesting, brick making as well as fire. Overall, the final project evaluations identified that projects had little success in addressing energy drivers for a range of reasons – including insufficient or incomplete strategies, interventions, capacity and/or budgets. Most drivers are outside the forestry sector and require skills beyond the core competencies of many conservation NGOs. The creation of new partnerships between conservation NGOs and external service providers was a valuable approach in increasing local effectiveness. Interestingly, although all the projects identified population growth as an important driver of deforestation, only JGI had family planning and reproductive health activities (which were funded separately). Despite the complexity, a key lesson learned from TFCG/MJUMITA, as well as the MCDI projects, was the need to first understand and prioritise different drivers and then work on the principal driver in a focused manner. Focusing on multiple drivers is complex and results easily in overall loss of efficiency.

Almost all the pilot projects in Tanzania conducted studies to identify deforestation drivers, but only MCDI s studies resulted in a major change in approach. The pilot projects mostly focused actions on activities that had been already defined in the original project document. The MCDI project did, however, completely redirect its emphasis due to the findings of research conducted to identify deforestation drivers. Originally the project aimed to address the two drivers of shifting cultivation and charcoal production. Further study revealed however that in Kilwa district population pressure was still low, and that forest cover change was primarily driven by wildfires, which occur every one to three years at the peak of the dry season. The annual forest carbon loss through wild fires exceeds by 60 per cent that caused by shifting agriculture. The project now concentrates on the introduction of fire management through early burning, practised by VNRCs. This is a relatively low cost intervention with the potential for scaling up to other areas of the country facing similar conditions.

13

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

Addressing the most important driver, smallholder agriculture, has had some success but it is expensive and time consuming. It will be impossible to scale up impacts without extensive collaboration with agricultural research and extension organisations. Agriculture drives D&D either through the opening of new permanent farming areas or through the slash-and-burn plots, and is the most important driver in pilot project areas. This has been addressed by participatory land-use planning, improved agricultural extension services and increased enforcement of local by-laws that control the use of the village land and forest. Planning to zone the village area has achieved a significant change in land use patterns in the AWF villages in Kondoa; by-laws are now enforced to regulate the number of cattle, to restrict grazing from erosion-prone areas and to regulate the use of village forests. Furthermore, land use planning teams active in land management and governance have been created, such as in TFCG and AWF villages. In Zanzibar, community forest management areas (CFMAs) identified core REDD+ forests and utilisation forests where shifting agriculture can also be practised by obtaining a permit from the Shehia Conservation Committee. On the islands, land is limited and it is of crucial importance to address agricultural productivity if emissions are to be reduced. Food security is a major issue as drought, labour constraints and low yielding varieties prevail in rural Tanzania; more forest needs to be converted to subsistence crops such as maize and also sesame, which is an increasingly popular cash crop due to growing international markets. TFCG worked on conservation agriculture by training and subsidising farmers to use better maize seed, and improve soil moisture retention and crop spacing, showing that a major increase in production could be achieved.

Summary of key messages

n The main drivers of forest degradation, as identified by the pilot projects, are the growing energy needs of an expanding population, coupled with small-scale agricultural expansion. At the local level, drivers are complex, multi-sectoral and often interlinked.

n After detailed studies on local drivers of deforestation and forest degradation (D&D), pilot projects experimented and tested a range of different tools and approaches for addressing the drivers with varying degrees of success, effectiveness and efficiency.

n Identifying the models and approaches that can be taken to scale is a crucial part of achieving emission reductions and other REDD+ results under a national or jurisdictional approach. Pooling resources and creating partnerships with non-forestry organisations and institutions is an effective approach to addressing the agriculture and energy drivers in a strategic and cost-efficient way.

n Participatory forest management (which in turn emphasises the creation of local incentives for sustainable forest management), community-based fire management and conservation agriculture appear to be the most effective approaches in addressing deforestation drivers in the Tanzanian context.

14

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

5Adapting participatory forest management to a REDD+ context

PFM in Tanzania – legal basis and current statusThere is a considerable overlap between the goals of REDD+ and PFM with regard to the long-term protection and management of natural forests. Overall, both PFM and REDD+ aim to maintain forest cover, reduce conversion to other non-forest land uses, restrict unsustainable resource use, and generate long-term benefits to local users. As such, PFM is increasingly seen as a means to address local deforestation drivers. In countries with a strong legal jurisdiction relating to community tenure over land and forests, such as Tanzania, Nepal, Bolivia and others, PFM is being used as a basis for advancing REDD+ (Newton et al. 2014). Tanzania’s national REDD+ strategy describes PFM as ‘a valuable basis for REDD+ readiness’ (p. 9) and proposes using REDD+ finances to scale up PFM across Tanzania as a way of reducing prevailing high levels of deforestation and forest degradation (p. 19) (URT 2013).

Tanzania has a well-established PFM programme that builds heavily on existing land and local government laws. Two forms of PFM exist in Tanzania – joint forest management (JFM) and community-based forest management (CBFM) (Blomley and Iddi 2009).

n Joint forest management is a collaborative management approach, which divides forest management responsibility and returns between government (either central or local) and forest adjacent communities. It takes place on land reserved for forest management such as national forest reserves and local government forest reserves. It is formalised through the signing of a joint management agreement (JMA) between village representatives and government (either the district council or the Tanzania Forest Service).

n Community-based forest management takes place in forests on ‘village land’ (land which has been surveyed and registered under the provisions of the Village Land Act (1999) and managed by the village council). Under CBFM, villagers take full ownership and management responsibility for an area of forest within their jurisdiction. Following the legal transfer of rights and responsibilities from central to village government, villagers gain the right to harvest timber and forest products, collect and retain forest royalties, undertake patrols (including arresting and fining offenders). In addition, they are exempted from local government taxes (known as ‘cess’) on forest products and are not obliged to remit any part of their royalties to either central or local government. The underlying policy goal of CBFM is to progressively bring large areas of unprotected woodlands and forests under village management and protection through the establishment of Village Land Forest Reserves.

15

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

As of 2008, more than 2,300 villages (18 per cent of all villages nationally) had become engaged in PFM, with 1.6 million ha of forest under JFM and 2.1 million ha under CBFM, representing about 11 per cent of all forested land in Tanzania (Blomley et al. 2008). Since 2008, PFM has continued to expand, much of it with support from REDD+ pilot projects in different regions of the country.

PFM and REDD+Within the context of REDD+ pilot projects in Tanzania, most projects supported some form of community involvement in forest management as a means to reduce deforestation and forest degradation. Pilot projects directly supported PFM processes in over 491,000 ha of woodlands and forests across the country. Some projects have helped communities gain legal title over land and forests through the establishment of village land forest reserves (CBFM), while other projects carry out JFM initiatives around forests managed by central government – often with high biodiversity values. One project (JGI) supported the emergence of new forms of forest management – where previously unreserved forests were managed under an inter-village community-based organisation. The absence of any recognised legal framework for this arrangement has however meant that by the end of the project, forest tenure for this area of forest remains unresolved.

At the time when REDD+ was being endorsed by government as a new policy, views were mixed, both in Tanzania and elsewhere, regarding the potential impact of REDD+ on forest and land tenure rights. Some feared that increasing the value of natural forests through REDD+ could lead to a ‘resource grab’, involving either the government recentralising control over forest tenure, or powerful private sector interests buying up, or leasing, large areas of forested land and excluding local users in the process (Phelps et al. 2010). Others were concerned that REDD+ would lead to the return of ‘fortress conservation’ by both government and conservation NGOs, justifying a return to evictions and displacement of forest dependent communities (Beymer-Farris and Bassett 2012). Others struck a more optimistic note, suggesting that if well implemented, REDD+ had the potential to ‘unblock’ systemic or structural barriers that have hindered PFM’s expansion and adoption across the remaining unreserved forests in Tanzania (TFCG 2009). The following section discusses whether these hopes and fears have played out in practice through the implementation of the REDD+ pilot projects across different parts of the country. We review whether REDD+ helped or hindered the dissemination of PFM, by attempting to answer some key questions relating to effectiveness and impacts.

Did PFM lead to better forest management and reduced emissions?PFM was designed, primarily, as a tool to support improved forest management. A number of studies have been undertaken in Tanzania to assess the performance of PFM against this goal. Although results are somewhat mixed, the general consensus has been that forests managed either fully or jointly by communities tend to be in better condition than those managed exclusively by the state (Blomley

16

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

et al. 2008, Persha and Blomley 2009; Lund and Treue 2008 and Treue et al. 2014). These findings confirm similar studies on the performance of community forestry elsewhere in the world (Bowler et al. 2010). However, the results are not entirely consistent – a recent study of seven forests under CBFM and three under JFM showed that half were being managed unsustainably, with extraction levels exceeding annual growth rates (Ngaga et al. 2013).

The advent of REDD+ has sparked a discussion regarding the impacts of PFM at a wider level of scale and the impacts of improved protection in one area on adjacent areas of forest, which are not subject to such stringent management practices. The displacement of harvesting from one area to another (known as ‘leakage’) may be widespread, leading to negligible net changes in deforestation or forest degradation at higher levels of scale (Balooni and Lund 2014). Much of the PFM promoted prior to the advent of REDD+ in Tanzania was designed to assist communities to protect forest areas that were important to them. This could be water sources, cultural or traditional forest areas, or areas used for grazing livestock during the dry season when other grazing areas are exhausted. In many cases, these areas represent the best-managed forests within their village area. CBFM, in effect, becomes a tool to protect areas that were not under a significant threat of deforestation, but perhaps subject to limited unregulated use and in need of improved management. Given a free choice, experience with CBFM to date in Tanzania has shown that villagers will set aside a relatively small proportion of their total forest area for protection and management, while leaving a relatively larger area for future agricultural expansion or harvesting for timber, firewood or charcoal (Morgan-Brown 2014). Under prevailing models of CBFM, therefore, harvesting and forest clearance continues in unreserved forest areas on village land, while small village land forest reserves are protected by village governments. The net effect across the whole village land area, however, is continuing forest clearance and conversion to alternative land uses. This implies a more holistic approach that considers trees both within and outside village-managed protected areas, the use of village land use planning tools, and the application of village by-laws to cover all trees within the village area.

One potential solution to this challenge lies with participatory land use planning (known in Tanzania as village land use planning (VLUP) to reflect the importance of village governments as a level of scale for planning and the institutional structures in which planning is embedded). While the national land use planning guidelines issued by the Ministry of Lands and Human Settlement (URT 1998) emphasise the importance of reserving locally important areas of forest for community use, the primary focus is on calculating and allocating future agricultural land use needs and zoning forest areas accordingly (Morgan-Brown 2014). As such, VLUPs promoted across Tanzania represent a ‘business as usual’ (BAU) scenario where forest is cleared as demands for land increase in line with population trends, based on current use patterns. Under REDD+ however, project proponents need to show how the BAU scenario will be altered through the actions of the project (for the purpose of demonstrating additionality).6

6. ‘Additionality’ in this context refers to evidence that any reduction in emissions from a REDD+ project is genuinely additional to reductions that would occur if that project were not in place.

17

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

Community-based land use planning is widely seen as a way in which local land use decisions can be effectively planned and regulated and as such have been strongly supported by REDD+ projects, both in Tanzania and elsewhere. However, experience has been very mixed. One of the main criticisms has been that plans are done as ‘one-off’ exercises, rarely followed up, and with no real framework for implementation or monitoring built in. As such, there are few sanctions if plans are not followed, and no incentives in place to encourage plan implementation (UN-PEI 2008). In other parts of the world, participatory land use planning has been criticised as it has failed to link to and address the real drivers of land use change (such as incoming private sector land-based investors with high level political linkages) (Rock 2004). In the Congo Basin, the effectiveness of participatory land use planning was found to be relatively limited due to insecurity of land tenure. Land users are generally not landowners and therefore not empowered to take long-term decisions, and they lack any incentives to undertake long-term investments designed to improve productivity (Yanggen et al. 2010).

Two of the REDD+ pilot projects (TFCG and AWF) used land use planning as a tool to address issues of leakage. By working with a series of neighbouring village areas, they were able to establish land use planning across a relatively wider area. In both cases, efforts were taken to ensure widespread participation in the production of the plan, and in the case of TFCG, the VLUP formed the basis of discussions (and eventually, a signed agreement) around securing free, prior and informed consent (FPIC). Contrary to experiences elsewhere, implementation of the plans appears to have taken place relatively effectively. The underlying reasons for this were found to be three-fold. Firstly, there are sanctions for infringements of agreed plans. These include fines levied by the village government using village by-laws, and also reduced revenues from REDD+ dividends, caused by non-performance. Secondly, the plans were closely anchored to village governments, which as legally mandated, government institutions had authority and responsibility to oversee implementation. Thirdly, the plans were developed in a participatory manner, reaching down to sub-village level and ensuring broad input from across the community.

Did PFM generate tangible benefits for local forest users and managers?Although PFM in Tanzania has made considerable progress in achieving a significant level of scale and adoption, research has shown that it has yet to generate notable and tangible economic incentives for local forest users (Persha et al. 2014). A study conducted in southern Tanzania established that, in 14 villages with village land forest reserves averaging around 2,600 ha each, villages generated annual revenues of around US$540 per year in 2002, rising to around US$720 per year by 2005 (Lund 2007). Finances generated from JFM areas are much less – averaging US$189 per village per year (Blomley and Ramadhani 2006). The reasons for this relatively low generation of income are many, but include the fact that many CBFM sites were degraded when handed over to communities and required a long lead-in time while forests recovered and until sustainable harvesting could be undertaken at a significant scale. Secondly, forests under JFM tend to be high biodiversity areas with very limited legal use and hence almost no opportunities for commercialisation of harvested forest

18

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

products. Thirdly, there is a prevailing belief among many government foresters that forests should be protected, conserved and subject to minimal levels of forest harvesting (Blomley et al. 2009). At the same time, PFM has involved significant opportunity and transaction costs for communities, in terms of foregone forest use and individual and institutional time committed to forest management operations (Merger et al. 2012). Financing from REDD+ has been seen by some as a means through which these costs can be offset (Khatun et al. 2015).

Most of the NGOs implementing the pilot projects (with the exception of CARE International and possibly MCDI) have a clear mandate and goal to protect and conserve biodiversity. As such, a number of organisations began discussions with communities over the conservation and protection of forests in ways that limit or minimise local use. In the case of JGI, this initial starting point proved untenable and communities made it very clear that some form of sustainable use would be needed if community support was to be secured, primarily to cater for local, domestic needs for firewood and other forest products.

Despite local demands, most NGOs considered that sustainable, commercial extraction of forest produce was considered complex, risky, likely to generate high emissions and hard to account for. TFCG have a sister project working within one of their two project REDD+ pilot areas that is supporting sustainable charcoal production within four of the REDD+ project villages. At around US$25 per ha per year, sustainable charcoal production generates more revenue per ha than when managed for REDD+ (with no commercial use). As such, there are trade-offs to be made between generating carbon credits (where use is minimised) and generating revenues from sustainable harvesting. TFCG analysis suggests that sustainable charcoal production results in 50-70 per cent permanent reduction in the carbon stocks of the areas being managed when compared with strict conservation.

Although projects have generated important co-benefits (such as improved land and forest tenure rights), it is looking increasingly likely that the interests of communities might have been better served if external support had been directed to helping communities access less risky and more accessible markets for sustainably harvested forest products (such as charcoal and timber). Being driven by the externally defined goal of reducing carbon emissions (with the expectation that performance-based payments would continue in the long term through voluntary market carbon sales), local goals for forest management appear to have been displaced. This is made more worrying by the fact that long-term payments have yet to materialise.

In effect, the MCDI project has addressed this concern, as its primary focus is helping communities establish secure rights to land and forest and then helping them to develop sustainable harvesting of FSC-certified timber for export markets. Payments from reduced emissions (which it is hoped can be secured from the sale of verified credits on the voluntary carbon market) will not go to communities, but instead be used to fund the expansion of CBFM and sustainable forest management by the implementing agency (Ball and Makala 2014).

19

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

Four of the REDD+ pilot projects included trial payments within their budgets with the aim of making ‘front-loaded’ payments to test benefit-sharing mechanisms and generate early incentives for improved forest management. This had the effect of putting cash in the hands of either individuals or elected village institutions and was an important catalyst for local level forest management.

Did REDD+ help speed up the formalisation process for PFM agreements?Joint forest management has been a high priority for both government and development partners, given its potential to help protect high biodiversity forest reserves under threat from encroachment and unregulated harvesting (Blomley and Ramadhani 2006). However, although many agreements have been successfully negotiated, a limited number have been formalised through the signing of legally binding agreements, as specified in law. Data provided by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism in 2008 found that across mainland Tanzania, 863 villages were involved in JFM processes, and only 155 (18 per cent) had resulted in signed agreements (URT 2008). A more recent study of JFM across 110 randomly selected JFM sites found that only 8 per cent had signed JMAs (Persha et al. 2014). One of the underlying reasons for this is that while forestry laws provide for JMAs, they are silent on how management costs and benefits should be shared. The matter is further complicated by the fact that much of the JFM in Tanzania is concentrated in high biodiversity forests. While these forests deliver a range of crucial environmental services to the nation (through conservation of water sources that provide water for drinking, industrial use, irrigation and power generation) and the global community (through conservation of biodiversity), their contribution to local users is highly limited as consumptive use is heavily restricted (Blomley and Iddi 2008).

Of those JMAs that have been signed, the general trend is that agreements are made to cover a period of five years. While this does, potentially, provide opportunities for the agreements to be revisited and revised after a five-year period, it does leave the door open to agreements not being renewed, thereby leaving communities in a somewhat precarious position of investing time and effort in the hard work of restoring forests – only to have any negotiated access rights taken away once the forest condition begins to improve. Many forests targeted under JFM were in a poor condition, having been subjected to decades of neglect and poor management by central government. Although no nationally agreed ratios were developed until 2014, agreements that were concluded generally left communities with 20-30 per cent of benefits that were accrued from forest management, with the remaining balance going to either central or local governments (Blomley and Iddi 2008).

Despite these evident risks, two of the REDD+ pilot projects opted to work in forest areas administered by government and proposed the development of legally binding agreements over the shared management of forests. AWF, working in Kondoa district, targeted Isabe and Salanaga Forest Reserves, which are under central government management. CARE International, working in Zanzibar where

20

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

all land is administered by the Zanzibari government, proposed to facilitate the agreements for the joint management of CFMAs. Perhaps as a result of the relatively high political profile accorded by being REDD+ pilot projects, both projects were able to successfully negotiate legally binding agreements between communities and government over forest management within a relatively short period. Given demands for permanence under REDD+, agreements in both sites have been made, covering a period of 30 years. Furthermore, both agreements specify clear agreements on how forest management benefits (in this case revenues from the sale of voluntary market REDD+ credits) are shared, which in both cases resulted in more than 80 per cent of net REDD+ dividends being allocated to communities or community organisations.7

Did REDD+ help with the low economic viability of small and fragmented forest patches managed under PFM?Although the total area of unreserved forest in Tanzania remains relatively high, the average size of forest areas reserved by village governments remains relatively small. Data from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism suggests that the average area of village land forest reserves in Tanzania is around 1,600 ha (URT 2008). The poor condition of many of these forests when they were incorporated under community management, coupled with limited use options imposed by village governments, means that opportunities for sustainable harvesting are limited (Mustalahti and Lund 2009). Under REDD+, given low carbon prices, total forest areas being managed need to be significant if they are to generate any appreciable revenues to local managers.

Within the context of REDD projects, forest areas managed by communities varied significantly. In the context of the TFCG/MJUMITA project, village forests varied between 1,500 to 8,000 hectares, while in another project working in central Tanzania (TaTEDO) village forests were much smaller (1.5-10 ha each). At the level of the individual community, small forest size and the transaction costs of measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification were considered too high to support the marketing of carbon credits and as such, a common feature across many projects was the creation of an ‘aggregation entity’. These were in effect intermediary organisations, designed to represent local interests by reducing REDD+ transaction costs for individual participating villages and increase economies of scale.

As none of the pilot projects have yet to sell carbon credits on the voluntary market, none of these bodies have become fully operational. However, useful lessons can be drawn from the experiences so far. Different projects attempted this in different ways. TFCG/MJUMITA proposed establishing a community carbon enterprise, which would be accountable to individual member villages involved in selling carbon but would bundle credits from across all villages for sale to potential buyers.

7. In the case of the AWF project in Kondoa, a ratio of 80:20 was agreed between communities with signed agreements and central government, while in Zanzibar, 50 per cent of gross revenues was agreed for communities with CoFMAs, 35 per cent to a civil society organisation representing CoFMA interests and the remaining balance to tax and project developers.

21

Natural Resource Issues No. 32

MJUMITA, which operates as a loose network of community forest user groups, has established contracts between itself and each participating village government. In Zanzibar, CARE International helped create a new institution – JUMIJAZA, a network of individual community forest management associations (CoFMAs), which, it is hoped, will aggregate and sell verified emission reductions (VERs) to the international carbon market. Trial payments (included within the project budget) were made to individual CoFMAs through local management structures (known locally as Shehia Conservation Committees). JGI, in their project, facilitated the emergence of an NGO (known by the Kiswahili acronym – JUWAMMA) – that was constituted from individual village governments for the shared management of the Masito forest.

Institutional capacity and sustainability of intermediary aggregation bodies is a key issue identified by a number of projects, with the conclusion that capacity development efforts need to be targeted towards such institutions at a very early stage in project implementation, and sustained investment needs to be made over a long period (Jarrah 2014). By the end of donor funding, few if any of the aggregation entities have either the capacity or financial flows to be able to operate independently of NGO support, and poor results in selling carbon credits has further undermined their long term viability. Despite their limited effectiveness, however, they do offer potential insights into how products (both carbon and non-carbon) could be marketed and sold from forest areas, which on their own would not be seen as economically viable. MCDI is already in the process of establishing a community-driven intermediary organisation that builds on these experiences, representing village level interests in the marketing and sale of certified timber from village forests (Ball and Makala 2014). Such models could usefully be scaled up in other areas where communities have expressed interest in collaboration around the sale of sustainably-harvested forest products, such as charcoal or timber.

Summary of key messages

n The use of participatory forest management (PFM) as a principal tool for addressing local deforestation drivers within the context of REDD+ has generated useful lessons and experiences when compared to previous, more established approaches to implementing community forestry in Tanzania.

n Externally-defined objectives of reducing carbon emissions (which call for large areas of forest to be protected) may conflict with local demands for expanding agricultural production due to growing demands for land; and such trade-offs need to be negotiated in a participatory and inclusive manner.

n Approaches to community-based forest management (CBFM) as practiced across Tanzania over the past two decades may be resulting in high levels of leakage, as management efforts tend to be strongly focused on the management of village land forest reserves, but with little attention to the management of trees on village lands, outside community protected areas.

n Demands under REDD+ for ‘permanence’ are providing impetus for the extension of JFM agreements of up to 30 years in duration, which provides increased tenure security for local communities.

n Fragmented, dispersed and relatively small sites managed under PFM require aggregating entities to be able to present larger, economically-viable volumes of carbon to the international voluntary carbon market.

22

Natural Resource Issues No. 32