RCSS Policy Studies 20 · RCSS Policy Studies 20 Globalization and Multinational Corporations in...

Transcript of RCSS Policy Studies 20 · RCSS Policy Studies 20 Globalization and Multinational Corporations in...

Regional Centre for Strategic Studies

RCSS Policy Studies 20

Globalization and MultinationalCorporations in South Asia:

Towards Building a Partnership forSustainable Development

Arjun BhardwajDelwar Hossain

Published by:Regional Centre for Strategic Studies2, Elibank RoadColombo 5, SRI LANKA.Tel: (94-1) 599734-5; Fax: 599993; e-mail: [email protected]: http://www.rcss.org

© Regional Centre for Strategic Studies 2001

First Published: July 2001.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, storedin a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,mechanical or photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the priorpermission of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies. It is distributedwith the understanding that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise besold, lent, hired or otherwise circulated without the prior consent of theRCSS.

Views expressed in materials published in RCSS Policy Studies are ofcontributors, and not necessarily of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies.

Printed by:Design Systems, Colombo 8.

ISSN: 1391-2933ISBN: 955-8051-21-7

In memory of Delwar Hossain’s father,the late Faizuddin Ahmed, who left for his heavenly abode

on 20 August 2000

Foreword

The concept of security has undergone major changes both globallyand regionally in recent years and particularly after the end of the ColdWar. Central to this question is what is it that we want to secure? In the eraof strong state nationalism, the answer was obvious. It was the territory ofthe nation state and national interests. This idea held sway till the end ofthe Second World War and even afterwards. It was common under theseconditions to expect the citizens of a nation to unquestionably lay downtheir lives, in defence of both these causes. This idea no longer holds at theend of the Cold War. The developed western countries today find it difficultto justify the loss of life of a single citizen whatever be the cause. This islargely because, security in the minds of people today have come to acquireentirely different connotations.

In truth security is far too interdependent and fundamental an issue,which cannot be defined in purely military terms. It is no longer my securityagainst yours, but my security AND your security, in a global environmentwhere all are equal stakeholders. With this concept has also developedgreater tendency for regional cooperation to further both national andregional interests.

It was with this aim and with support from the Ford Foundation, thatthe Regional Centre for Strategic Studies initiated a project on NonTraditional Security Issues in South Asia, as part of an Asia wideprogramme, to examine these emerging conditions of security. The topicsaddressed in this first phase were; Globalisation and Security, Governancein Plural Societies and Security and Environment and Security.

The principal studies on the above three topics were conducted byleading experts of South Asia and have resulted in independent books.Simultaneously, the RCSS also asked younger scholars to examine each ofthese issues from their own perspectives. The Centre decided to name thesecompetitive regional research projects as Mahbub Ul Haq Awards. ThisAward, which has led to three RCSS Policy Papers, is a comparativelysmall part of that overall programme. A unique feature of these Awardswas that scholars from two different countries of South Asia wouldcollectively address each topic. The extensive network developed by theRCSS made this possible.

We are indeed fortunate to be allowed to name these studies afterMahbub Ul Haq (1934-1998), a most distinguished South Asian scholar

of contemporary times, whose contribution to our understanding of‘development’ is internationally acclaimed and in particular his work onHuman Development Reports. He was a pioneer in the propagation ofthe concept of human development model, “the basic precepts of whichare to improve capabilities and expand opportunities of all people,irrespective of class, caste, gender and ethnicity.” Not only did he speak ofthe intensity of deprivation in the region, but also strived to bring to lightthe reason for such misery and mayhem. He was determined in his studyon South Asian countries to bring to light the oppressive political, economicand bureaucratic systems in the region. His work spanning over thirty yearswas dedicated to analysing how far governments affected the lives of itspeople-politically, economically and socially.

We humbly dedicate these three volumes to his name with the kindpermission of his equally well-known wife, Ms Kadija Haq, who continueshis work today.

This current work on Globalisation and Multinational Corporationsin South Asia, is by Delwar Hossain from Bangladesh and ArjunBhardwaj from India. It reflects their collective view on this issue ofmajor concern to the region.

Dipankar Banerjee June, 2001Executive Director

Preface

Globalization is not a new phenomenon. What is new is its speed andreflexivity given its complex nature and the gravity of impact on states andsocieties. Contrary to interdependence, it refers to a gradual and ongoingexpansion of interaction processes, forms of institutions, and forms ofconflict and cooperation, cutting across domestic and internationalboundaries. It covers the entire gamut of economic, political, social andcultural development across the world marked by the dramatic spread ofthe market economy and democracy in the post-Cold War period.Multinational Corporations (MNCs) are a driving force behind the processof globalization. The relationship between MNCs and globalization iscomplementary since one reinforces the other. Under the conditions ofglobalization, MNCs are increasingly becoming major players at bothdomestic and international levels. Many of the costs and benefits ofglobalization are closely linked with the operations of MNCs. On the otherhand, empirical evidence suggests that globalization is becoming both athreat and an opportunity for non-traditional security in many different ways.For example, threats are manifested (among other ways) by widening therich-poor gap, social instability and increasing environmental degradation,while opportunities have shown up in forms of faster economic growth,more technology transfer, and increased democratization. In this context,the imperative of sustainable development could address the pitfalls andpromises of the process of globalization.

We, therefore, argue that the phenomenon of globalization is stronglylinked to sustainable development, and we have analysed these linkages inthe context of the environment in South Asia. Sustainable developmentaddresses the problems of global security. Developing countries have alwaysclosely examined the costs and benefits of the entry of multinational firms.Before the 1990s, relations were antagonistic, driven partly by ideologicalconsiderations and partly due to irresponsible behaviour by many largecompanies which led to horrible industrial tragedies. In the 1990s, therehas been an increasing acceptance of MNCs in South Asia, and there havealso been concerns of building partnerships with MNCs and elicitingstronger participation from them in the sustainable development process.In our study, we focused on companies in India and Bangladesh and triedto identify the trends of foreign direct investment (FDI) as well as closelyexamine some of the development efforts of MNCs. We discovered theruthless decision-making processes in these companies and the pressureunder which professionals perform. Our search for role models of partnership

also led us to look extensively at the strong partnerships which theIndian company Tata Steel had created in the development process, withoutactually using too many of their own resources. We felt that managerialskills at MNCs could add great value to the processes of sustainabledevelopment.

When we took up this challenging assignment of identifyingpartnerships between MNCs and host governments in South Asia, inunderstanding the new emerging security paradigm and to focus onopportunities and areas of collaborative efforts between MNCs and otherstakeholders in the sustainable development process, we did not have toomany leads to follow. Scanning existing literature and talking to executivesacross the corporate sector, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) andpolicy makers helped us build a perspective on the ways these differentorganizations approached the prospects of being partners in the sustainabledevelopment process. We studied many MNCs and their efforts in thedevelopment process in the host nations, and discovered a few where wefound examples of remarkable collaborative efforts in which the corporatesector played an important role.

Contents

I Introduction 1

II Scope of the Study and Hypothesis 5

III Globalization, Security, andSustainable Development 9

IV Implications of Globalization:A Critical Overview 25

V Multinational Corporations: Changing Strategies 30

VI Multinational Corporations in South Asia 36

VII The Indian Example:Case Studies of Enron and Tata Steel 45

VIII A Case Study from Bangladesh 59

IX The Road Ahead 65

Notes and References 68

Bibliography 73

10 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 11

I

Introduction

With the process of globalization, the traditional power and authorityof nation states have come under scrutiny. As Edwards argues, changes inthe distribution of power and authority are characteristic of the processeswe call globalization.1 While the ‘globalists’ argue that globalization willcontinue until there is a “borderless or seamless” world in which the non-state actors will play a substantive role, the ‘internationalists’ feel that theprimary actors will continue to be nation states. Despite considerable debate,the fact lies that although the role of the state has not diminished, it haschanged to a great extent. Two non-state actors which structure globalpolitics and economics in the age of globalization are the private sectoractors of MNCs and NGOs. The rising power of MNCs, particularly, in thepost-Cold War era generates a paradoxical situation for governments ofdeveloping countries. On the one hand, they need to attract the capital,management skills, technology and global market access that MNCs canprovide. On the other hand, they need to be sensitive to the potential dangersof transfer of important assets from domestic hands to foreign control.2

The urgency of action is now particularly great: not only is the volume ofFDI booming, but the strategies being deployed by transnationalcorporations (TNCs) are also giving them increased leverage. Globally, thecorporate world is becoming increasingly intertwined. The MNC is both avehicle for generating FDI as well as a product of it. This trend towardsMNC-based foreign investment is likely to continue as a result of theglobalization of markets for goods, services, and capital.

In this context, the role of international financial and economicorganizations is vastly favourable for MNCs. The World Bank andInternational Monetary Fund (IMF) have systematically undertaken“structural adjustment programmes” around the world by attachingconditions to use their lending to help adjust economic structures of debtornations to suit the purposes of world development strategies with the aimof opening economies to markets. These programmes have clearly benefitedlarge multinationals, ruling elite, and the lenders themselves. The nationalresponse to the 1997–8 financial crisis in Asia is a good example. Despitethe crisis, economic, social and technological forces towards globalizationremain strong. The IMF-host country agreements reduced restrictions onforeign ownership of land and investment, placing forest and land resources

12 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

more directly under the influence of global market forces and foreigncorporations. In fact, much globalization is driven by MNCs. Competitionamong MNCs is intensifying at the global level, and the pressure to keepcosts down forces them to locate in or relocate to countries that offer first-class conditions. This will influence global investment patterns and hasimportant consequences for South Asia.

Concern about increasing corporate power was clearly voiced in the10th UNCTAD conference held on 12–19 February 2000 in Bangkok, whereAsian leaders talked about the growth and increasing power of huge MNCs.In a speech to at conference, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamadsaid he was “worried and frightened” by the speed at which companieswere merging to seek domination of some global industries. Chambersmaintains that in the 1980s and 1990s, the World Bank, IMF and otherbanks and donors set conditions for domestic economic policies in the Southto a degree unthinkable in the 1960s or 1970s. More than ever before, poweris concentrated in the cores of the North, including power to determinenational policies in the South.3 The 1999 Human Development Report states,“…the new rules of globalisation—and the players writing them—focuson integrating global markets, neglecting the needs of people that marketscannot meet. The process is concentrating power and marginalizing thepoor, both countries and people.” In addition, pressures from internationalfinancial institutions, trade organizations and international financial marketsseverely constrain the developing world governments’ ability to design theirown development strategies and to establish fair and equitable relationsbetween host countries and the multinationals.

Against this background, the developing world in general, and SouthAsia in particular has been facing a major policy dilemma in the area ofFDI arising from the challenges of globalization. This has larger implicationsfor the security of South Asia by way of their role in economic development,environmental security and social resilience. The MNCs could play asignificant role in the development process of the nation state by generatingeconomic growth, exemplified in the case of East and South-East Asiancountries since the 1970s. Also, under Cold War assumptions, countriesare always prepared for emergencies, but economic integration andglobalization are helping alter this. As globalization accelerates andeconomies get integrated, political and security relations too enter a newera.4 Capturing some recent trends, it may be argued that globalization has,at a certain level, helped countries like Singapore buy security insurance,and multinational presence is also helping countries like India and Chinagain greater bargaining positions when dealing with developed countries.

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 13

A case in point was the sanctions against India after the nuclear blasts,where, ironically, it was large multinationals with high commercial stakeslike Enron, Coke and Pepsi which emerged as the biggest post-Pokhranlobbyists for minimizing the negative impact of sanctions on India.

The MNCs continue to be at the centre of the debate regarding thecosts and benefits of their operations in the emerging economies of SouthAsia. Many concerns about the exploitation of the Least DevelopedCountries (LDCs) by multinationals are accentuated by such incidents asthe Bhopal gas disaster in India and the Magurchara tragedy in Bangladesh.Issues of social responsibility continue to centre on the poverty, lack ofequal opportunities, environmental and consumer concerns, and the needto make MNCs partners in sustainable development. The MNCs concentratetheir R&D in home countries, restricting the transfer of modern technologyand know-how to host countries. Environmentalists and labour rightsactivists sharply criticize MNCs for endangering the ecological balanceand human rights. All these generate a complex situation for South Asiancountries in formulating policies concerning FDI. As globalization spreadsfast and economies get integrated, political and security relations too entera new era. Ironically, tons of research work has been done on the ratherantagonistic relationship between MNCs and host countries, but not toomuch research has been done on building bridges for collaborative efforts.This is an area we feel needs to be studied in depth.

Given these emerging trends and the significant presence multinationalshave in these developing economies and the increasingly important rolethey play in both the security and economy of these countries, governmentsrealize that there is a need for establishing and strengthening partnershipswith them and making them part of the sustainable development processes.Faced with intense pressure from environmental and human rights groupsnot only in host countries and elsewhere, these companies, in order to protectthere long-term interests, have also been under pressure to reconsider theirearlier policies and to use their strengths in terms of skills, resources andpower and take initiatives to make a fair contribution to the developmentof host countries. That begs the question as to what role can be played byMNCs in South Asia in making a positive contribution to sustainabledevelopment. How would the regional host governments be involved inthis process? Will the South Asian states continue to criticize the role ofMNCs? Or will they welcome FDI uncritically? Will the malpractices ofMNCs be repeated in neglecting the development of host countries? Will itbe worse now since they have a more favourable climate to manipulatetheir corporate interests? It is against this backdrop that this study examines

14 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

the role of MNCs in South Asia, taking into account the regional and globalchanges under conditions of globalization. The study also explores whatrole models of MNCs and policy responses of host governments’ areappropriate for the development of this highly underdeveloped region.

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 15

II

Scope of the Study and Hypothesis

With the end of the Cold War, security assumes an integrated approachencompassing socio-economic, environmental and human factors, whichclearly establish the primacy of non-traditional security in the whole gamutof the global security structure. Presently, two different trends of securityexist: one is a paradigm shift from conflict-based security to cooperativeand common security, and the other is the deepening of the security concernsof societies against the backdrop of persisting environmental, economicand social problems under the process of globalization. Given the changingperspective of security, sustainable development can best serve the non-traditional security interests of nation states. As popularly understood, theoperations of MNCs in many cases imperil the three components ofsustainable development—sustainability of economic growth, of humandevelopment and of ecology. In reality, as indicated earlier, MNCs couldplay a substantive role in the whole development process of nation states.Recently, several MNCs like Enron, Levi, Nike and Novartis have beenengaged in sociocultural development programmes in many host countries.These companies are also giving more attention to environmental and humanrights concerns. Although South Asia finds it difficult to attract global capital,there has been a significant presence of MNCs in this region. With theglobalization process, MNCs have become an inevitable part of thedevelopment process in almost all the economies of South Asia. Therefore,the major imperative for South Asian countries is to make these MNCspartners for sustainable development in this region.

Against this backdrop, the basic question upon which the study is basedis to investigate how South Asian countries are facing the dilemma of makingthe multinationals part of the process of sustainable development and toestablish long-term constructive and mutually beneficial relationships whichwould ensure non-traditional security at regional, national and individuallevels. The underlying assumption is that the process of globalization hascreated a compelling ground for both MNCs and state actors to look forareas of partnership in order to achieve mutual gains. Although state actorsare considerably constrained in their actions, in most cases it is theemergence of civil-society movements (specifically in the South) that, inplace of states, puts tremendous pressure on the behaviour of MNCs.Competing relations between the two non-state actors (MNCs and civil-

16 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

society organizations, or CSOs) provide an important opportunity for statesto redefine their linkages with MNCs. The basic question will be addressedby answering the following questions.

• How do we conceptualize the process of globalization? To whatextent have its various dimensions changed the focus of security?Why is the issue of sustainable development important in thiscontext?

• How do MNCs influence the directions of globalization? How isFDI related to MNCs? What are the strategies of MNCs? How dothey affect the interests of host countries?

• What are the trends, composition and sources of FDI in SouthAsia? What are the problems of the operations of MNCs in thisregion?

• Is it possible for MNCs and host countries in South Asia to forgemutually beneficial relationships in order to achieve sustainabledevelopment, thereby ensuring non-traditional security?

By answering these questions and investigating the main hypothesis,we aim to achieve the following objectives.

• To conceptualize globalization in relation to security andsustainable development.

• To analyse the expectations and perceptions of host governmentswith special reference to development and security needs;

• To identify possible areas of partnership.

• To recommend a policy framework in order to cater to thedevelopment and security needs of South Asian countries.

The study makes some assumptions. (1) That, for better or worse,the position of MNCs has been strengthened in the age of globalization. Anumber of domestic and international regulations along with fundamentalglobal structural changes precipitated by the end of the Cold War contributedto increasing corporate power. For instance, the investment relatedregulations of WTO and the proposed Multilateral Agreement on Investment(MAI) strengthened the bargaining power of MNCs vis-à-vis host countriesof the developing world. (2) That although developing countries are keento attract MNCs, they can neither accept the ever-increasing power of MNCs,nor orchestrate necessary policy measures at domestic or multilateral levelsin order to restrict their behaviour. (3) That the role of MNCs is perceived

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 17

in the changing conceptualization of security and development. (4) Thatthe issue of sustainability can bridge the gap between MNCs and hostcountries in South Asia.

Methodological Considerations

To achieve the above-mentioned research goals, we need toconceptualize the basic phenomena properly and to choose an appropriatelevel of investigation for empirical grounding. In addressing the conceptualquestions, the study has developed some operational definitions of keyconcepts and has made some assumptions, as indicated earlier. Thetheoretical framework of the study depends on conceptualization of thekey concepts to understand the interconnection between the three variables:globalization, security and sustainable development. The research techniquethat is likely to prove the most meaningful to provide empirical evidence inour study is an investigation of specific countries to illustrate how MNCsand host governments in South Asia could forge partnerships for sustainabledevelopment. India and Bangladesh were selected as cases in point.Compared to global models, which are too aggregative and prone to leaveout important details, our technique of studying specific countries wouldprovide factual and detailed information of considerable significance incrafting future policy frameworks to meet the challenge of globalization.However, the research design will proceed with the analysis of three crucialfactors: theorization of key variables by examining the linkages betweenglobalization, security and sustainable development; the salience of FDI asa force behind globalization; and the analysis of trends and directions ofMNCs in the globalized world economy. Finally, the study will seek toidentify issues of partnership between MNCs and host governments in SouthAsia in order to develop new policy responses to globalization. Apart fromdiscussing case studies, we have made a substantive review of literature.As a result, the study draws on both primary and secondary sources ofresearch materials. A series of interviews were conducted with scholars,government officials, businesspersons and citizens’ groups in Bangladeshin order to provide more empirical basis to the study.

Organization of the Study

The study is divided into seven sections. The first section introducesthe conceptual framework of analysis through establishing the key linkagesbetween globalization, security and sustainable development. The secondtakes a critical overview of the process of globalization and itsinterconnection with MNCs, besides examining how MNCs as agents of

18 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

globalization can influence the non-traditional security concerns, particularlythose of developing countries. The third section deals with the changingstrategies of MNCs with specific focus on historical analysis of MNCs–host country relations and corporate behaviour. The fourth section highlightsthe operations of MNCs and current trends of FDI in South Asia. It alsodwells on the changing perspective of host governments and MNCs’relations in South Asia. The fifth section looks at case studies on Indiawhile the sixth section focuses on the case of Bangladesh. In the final section,we examine some future trends in order to build up collaborative relationsbetween MNCs and South Asian states.

Limitations Of The Study

The study does not claim to represent the views of the developed ordeveloping countries in general, rather it examines the research question inthe context of South Asia to reflect the scenarios of the South inconceptualizing the triangular relationship between globalization, securityand sustainable development. Although this study provides an importantstarting place to investigate the emerging relationship between globalizationand non-traditional security in the specific context of MNCs’ operations, ithas two limitations. First, the data that ground this study are inadequate,which may constrain the generalizability of their findings. Second, theframework of analysis is not fully specified. The constructs and theirunderlying relationships require greater precision in order to be predictive.To understand sustainable development-oriented MNCs, we need to furtherexplore the contexts that precipitate these motivations and their interactions.

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 19

III

Globalization, Security, andSustainable Development

In this section we introduce a wider theoretical postulation of the keyvariables in order to understand their complex linkages. The process ofglobalization is treated as an independent variable, while the concepts ofsecurity and sustainable development are regarded as dependent variables.Another dimension of understanding the process of globalization is therelationship between globalization and MNCs. Through the channel of FDI,the MNC has emerged as a driving force behind the process of globalization.

Globalization

Globalization is not a new phenomenon. What is new is its speed andreflexivity given its complex nature and the gravity of impact on states andsocieties. Some argue that globalization has existed for centuries. Whilecontemporary globalization started after World War II, the earlier versionwas observed before the war. Keohane states, “Economic globalisation tookplace between approximately 1850 and 1914, manifested in Britishimperialism and increased trade and capital flows between politicallyindependent countries.”5 Chomsky argued that contemporary globalizationis rooted in the mid-1970s since when exchange rates were floated andlimitations on capital flows were eroded.6 More importantly, theintensification of the process of globalization has been linked with the endof the Cold War. Some argue that it is the ending of the Cold War thatfinally released the forces capable of propagating new socio-political andeconomic movements in domestic or external contexts in the absence ofstrategic obsessions of the two superpowers—the United States and theformer Soviet Union. Thus, the demise of the Cold War in 1990 marks anera of rapid and extensive global change.7 The economic, political andstrategic implications of this change are enormous.

While conceptualizing globalization, it is clearly observed that thenotion of globalization is subject to various interpretations, diversetheoretical frameworks and different kinds of empirical evidence. AsFriedman observes, the notion of globalization has been “discussed so widelyin scholarly and popular circles that it has reached the ignoble status of‘buzzword’, familiarly used by many to refer to some fuzzy phenomenon

20 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

or trend in the world, but hardly understood by any.”8 Despite this debate,the literature on globalization continues to proliferate, and the notion itselfoccupies the centrality of contemporary social science. The literature onglobalization demonstrates two diametrically opposite extremes in thecontinuum. Some strongly advocate the benefits and its overwhelmingpower to change the existing social phenomena, most notably, the role ofthe state.9 Friedman, a supporter of extreme globalization, argues that it is“the overarching international system shaping the domestic politics andforeign relations of virtually every country, and we need to understand it assuch”.10 Some argue that it is a myth and has no significant role in alteringhuman relations, while some take a cautious approach in assessing the costsand benefits of globalization, as the process itself is unfolding.

All debates on globalization eventually come down to either narrowdisciplinary boundaries or major theoretical approaches. It is a rather futileexercise trying to find out the loci of the debate in the disciplinary context asthere are many branches of human knowledge. So, it is appropriate to addressthe contending theoretical approaches behind the conceptualization ofglobalization. In this connection, we observe three different approaches: theliberal/neo-liberal thread; realism/neo-realism; and historical structuralism.While the neo-liberalists perceive the process of globalization primarily asan economic phenomenon prompted by market ideologies creating aborderless global economy with a substantive role of non-state actors, neo-realists question the existence of this notion and feel that the primary actorwill continue to be the state. So the realists tend to identify the process ofglobalization as “internationalization”, or “openness in the internationaleconomy”. On the other hand, historical structuralism argues that globalizationrepresents a power-domination dichotomy reflecting hegemonic relationsbetween the North and South. It emphasizes the characteristic features of theglobal economic system, which demonstrates an inherently imbalanced patternof international interdependence leading to inequalities within and amongcountries, perpetuating the dominance of powerful states and strengtheningcorporate power. However, this debate is presented in the subsequent section.

As indicated above, various approaches to globalization reflect a limitedunderstanding of the reality, since they are confined within particular researchagenda. So the fact is that no single approach can capture all the complexitiesof understanding the process of globalization. Therefore, we are better offwith a diverse array of competing ideas rather than a single theoreticalorthodoxy. Thus, arresting the salient features of different contendingapproaches, it may be argued that globalization is the outcome of the infusionof diverse and complex social realities generating from economic, political

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 21

and cultural contours. Some neo-realist assumptions such as state-centrism,presence of anarchy, possession of military power, and ally-enemy rotationmake us think critically about the process of globalization from the realistpoint of view. Similarly, the neo-liberal approach has established some validgrounds to consider the notion of globalization, given the overriding emphasison market mechanisms, liberal democracy and non-state actors such MNCsand CSOs, signifying the differences of values and identities as stressed bythe realists/neo-realists. The structuralists have also made strong argumentsif globalization is seen from the “bottom”. It may be argued that the notion ofglobalization emerges as an inevitable outcome of systemic evolution morein economic terms, and its emergence would rather accentuate structuralchanges at domestic and global contexts. Therefore, it is best perceived as amultidimensional spatial phenomenon, which is not an “event”, but a gradualand ongoing expansion of interaction processes, forms of institutions, andforms of conflict and cooperation cutting across domestic and internationalboundaries. It refers to the set of economic, political, social and culturaldevelopments across the entire world, marked by the dramatic spread of marketeconomy and democracy in the post-Cold War period. It covers a broad rangeof material and non-material aspects of production, distribution, management,finance, information and communications technologies, and capitalaccumulation.11 As a dynamic process, it introduces transformational changesin a range of human activities, generating a set of new conditions. Arguably,these changing new conditions drive the national structure to integrate intothe global system on the one hand; it generates changes in the rules the ofgame in domestic and international contexts, on the other. Prakash and Hartargue that globalization processes are initiated and encouraged by fourcategories of factors: technological change, spread of market-based systems,domestic politics, and interstate rivalries that clearly establish it an independentvariable (Fig. 3.1).

Spread of market institutionsDemocratizationInformation communication technologyCivil-society movementsInterstate rivalry

Process of globalization

Institutions of governance

Fig. 3.1 Globalization as an Independent Variable

22 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

Now it is pertinent to identify what the factors are that have beencatalysing the process of globalization by way of introduction of changesin rules and regulations in domestic and global contexts. We conceive thatfinancial liberalization, openness in trade, degree of privatization, level ofdemocratization, access to information and communication technology(ICT) and activity of CSOs are closely enmeshed with the process ofglobalization.

Financial Openness

The major defining character of contemporary globalization is ever-expanding capital movement across borders caused by financial reforms.World financial flows are so large that the numbers are overwhelming.12

These flows are largely liquid and are attracted by short-term speculativegains, and can leave the country as quickly as they came. Besides currencytrade, new financial instruments such as bonds, mutual funds, junk bondsand derivatives have emerged in the recent past, which have furthercontributed to the globalization of finance. Behind this movement of capitallies the opening up of the financial structure of a country, which dependson a number of concrete economic measures. As the World DevelopmentReport 1989 suggests, the major components of financial reform specificallyin the context of developing countries are (1) financing fiscal deficits, (2)interest rate policy, (3) directed credit, and (4) institutional restructuring.13

However, in reality, it is the process of deregulation of domestic economyfrom the control of the state that opens up the financial sector. Technologygenerates the environment of deregulation in many countries. For example,the invention of the cellular phone through lowering the cost brings manycompanies together in carving out the global market. Moreover, exchangerate reform through currency convertibility and devaluation and pricereforms provide a major push to financial openness.

Trade Liberalization

Liberalists maintain that unrestricted international trade maximizes totalworld income and welfare from a fixed quantity of available resources andtechnology. By contributing to a more efficient use of the world’s resources,liberalization by any country contributes to gains from trade.14 So tradetransactions both at domestic and international levels must be liberalizedthrough the removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers, which ultimatelycontributes to opening up external markets. For example, the export-ledgrowth strategy that contributed largely to the spectacular economicdevelopment of East Asian countries depends on trade liberalization. In

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 23

addition to domestic policy changes, the international regime under therules of the World Trade Organization (WTO) promotes an externalenvironment in liberalizing trade policies in both developed and developingcountries.

Privatization

Privatization is another major component of the overall process ofglobalization that promotes an economy where goods and services areproduced and distributed by individuals and organizations that are not partof the government or state bureaucracy. The issue of property rights, whichdepends on three interrelated issues (the concept of property, exclusive rightsto own, and transferability) is at the heart of the privatization process. Inthe capitalist economic system, privatization refers to the establishment ofprivate ownership of property through denationalization and thedevelopment of private entrepreneurship. According to neo-liberalism, it isan effective economic strategy to increase efficiency and productivity indomestic economy, thereby increasing the wealth of the nation. In reality, itcreates a profit-making capitalist class that might not contribute to nationaldevelopment. In contrast to industrialized nations, the privatization processhas not been contributing to national economic development in manydeveloping and transitional economies. However, under conditions ofglobalization it continues to be an important factor for economic change.

Democratization

Academic literature traces two causal paths linking globalization anddemocratization. Along one path, globalization promotes growth, which inturn promotes democracy. Along another, globalization promotes inequality,which creates instability, lower growth, and a degradation of democraticinstitutions. Drawing on endogenous growth theory, it is argued that thepath that prevails depends critically upon the nature of domestic politicalinstitutions, and especially the quality of capital-market (both financial andhuman) institutions.15 As advocated by neo-liberal thinkers, democracypromotes peace and economic development. Although it is debatablewhether globalization thrives on democratic impulses, political globalizationis almost synonymous with the establishment of a multiparty liberaldemocratic system. Democracy is defined as a political system whichsupplies regular constitutional opportunities for changing governmentofficials. It is widely held that democracy creates the enabling environmentin which market forces can perform their functions properly. Therefore,democratization emerges as an all-important issue after the end of the Cold

24 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

War. The level of democratization may be considered as a significantcriterion to measure how far a country is experiencing the process ofglobalization in the political sense.

Information and Communication Technology

The hallmark of globalization is the ‘technologization’ of trade.16

Recently, ICT has emerged as a paradigm of development given itswidespread impact on different facets of human life, thus becoming animportant force behind the process of globalization. Some argue that it isthe technological revolution as envisaged by Toffler in his famous workThe Third Wave which has been making the difference between the earlierand contemporary phases of globalization. In fact, ICT is considered as themain engine of economic growth for developed countries, and more so inthe coming decades. For example, the Organization for EconomicCooperation and Development (OECD) recently claimed that ICT is anenormous instrument to bridge the divide between the rich and poor, notjust the “digital divide” between those who have access to the Internet andthose who do not.17 There are three main components of ICTs: computing;communications; and Internet-related communications and computing.Particularly, the growth of the Internet marks an important breakthrough inthe economic and political domains of a country. The emergence of virtualstates, e-governance, e-commerce and so on has been changing the waysand operations of human activities.

Civil-Society Movements

Like ICT, the emergence of civil-society movements both in thedomestic and international contexts leads to the intensification of humaninteractions beyond the formal governmental process. This is more explicitlylinked with globalization, both as a cause and a way out. On the one hand,globalization by its emphasis on market forces and devolution of powercreated a wider role for CSOs, on the other hand local communities areforming networks of CSOs to address common concerns generated by thesame globalization. Civil-society movements are generally attributed tothe emergence of NGOs, non-profit organizations (NPOs), citizens’ andprofessional groups that have grown remarkably in variety and number inthe past 25 years. Though estimations differ, the NGOs listed in suchresources as the OECD Directory of NGOs, the United Nation DevelopmentProgramme’s (UNDP) Human Development Report and research based onthe Yearbook of International Associations all indicate a significantexpansion of the NGO sector.18 It is increasingly becoming a strong

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 25

phenomenon to exert considerable pressure on states and internationalorganizations in order to operate transactions in a certain direction.Interestingly, although CSOs generally oppose the process ofglobalization—or at least do the same in certain sectors like environmentand labour—in reality, they have become a significant force behindglobalization.

Of course, the politico-economic factors (such as financial openness,trade liberalization, privatization and democratization) have long beendiscussed, mainly under the framework of new-classical economics andthe modernization project since the 1950s. During the Cold War era, theimperative of preserving the capitalist system against the threat of Sovietsocialism always prompted the Western world to advocate these issues allover the world. But the difference in the present period lies with the factthere has been a global dominance of neo-liberal ideologies that addedspeed and reflexivity to the whole process. Equally important, ICTs andcivil-society movements are relatively new phenomena, cutting acrossterritorial boundaries, and all these create conditions conducive toglobalization. The preceding analysis demonstrates that the basic nature ofglobalization is economic, with related spillovers in political, cultural andsocial arenas. The underlying mechanism is the system of transnationalintegration and convergence in multiple sectors—trade, finance,communications, culture and employment. The major actors are nationalgovernments, international organizations, MNCs and CSOs .

Rethinking Security

Security at either national, or regional, or global levels has been widelycontested in its meaning and scope. For several decades, the predominanceof the realist paradigm defines security under the rubric of power.Conceptually, it was synonymous with the security of the state againstexternal dangers, which was to be achieved by increasing militarycapabilities.19 This state-centric definition emphasizes “self-help” andinternational “anarchy” in addressing the so-called “security dilemma” ofnation states. Balance of power or deterrence was considered the mosteffective instrument for bringing stability at regional or global levels. Theemergence of the Cold War in the mid-1940s and its sustenance can beattributed to the realist/neo-realist world view of the great powers in general,and the superpowers in particular. This resulted in the escalation of thearms race, interstate conflict and confrontation all over the world. Mostimportantly, it heavily undermined the real security needs of the Third Worlddeveloping countries. As Ayoob makes it clear, the quest for systemic

26 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

security actually increased Southern insecurity.20 However, the end of theCold War and other related developments in the early 1990s opened upopportunities for expanding the definitional boundaries of security in thereal sense. The widening of the scope of security has been recognized to agreat extent. The phenomenon of globalization, global concerns forenvironmental degradation and widespread global poverty have posed majorchallenges to the statist view of security.

Akin to the dominance of the state as security provider, Buzan makesthe most important and comprehensive re-examination of security in thepost-Cold War period.21 He clearly broadened the sources of threat, whichwere hitherto monopolized by military considerations, by including political,economic, societal and environmental concerns. More so, the level ofanalysis has been expanded to individual needs that fairly justify theimportance of human security. It may be noted that the re-examination ofsecurity goes back to the concept of “common security”, “comprehensivesecurity”, or “cooperative security” introduced much earlier in the 1980s.Mikhail Gorbachev proposed a comprehensive system of internationalsecurity in the mid-1980s, which would include disarmament as well asglobal economic and ecological security.22 Subsequently, the critical andfeminist perspectives have made important contributions to the redefinitionof security.

The Bruntland Commission of 1987, the protracted North-Southnegotiations, the Earth Summit in Brazil in 1992, the establishment of theCommission for Sustainable Development (CSD) and the GlobalEnvironmental Facility (GEF) and the publication of the HumanDevelopment Report provided an institutional environment to rethink thetraditional, statist concept of security. Based on the preceding analysis, weconceive security as a multidimensional and multilevel concept thatembraces an integrated approach by addressing the threats of diverse sources.A clear shift may be observed in the security paradigm from the traditionalmilitary to a non-traditional orientation, generating a transformation of state-centric threat perceptions. Also, a strong notion has been established thateconomic strength has replaced military strength as the measure of globalpower.23 As a result, the imperatives of economic development,environmental protection and human development come to the centre stageof security thinking. Some even argue that we are finally moving from thesecurity of the sovereign state to the security of the entire globe. Militaryinvasion and deterrence as observed in the Cold War era have becomeirrelevant, if not obsolete, in national strategies of survival. Now, whetherwe use the term “economic security”, or “environmental security”, or even

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 27

“military security”, instead of physical protection, development becomesthe overarching goal of security at every level. The pursuit of developmentis clearly linked with human survival.

The practical necessity of human life as embodied by “human security”becomes a fundamental issue in the whole security debate in the 1990s.The concept of “human security” is defined as the protection of humanbeings from material and non-material threats. It is an action-orientedapproach that focuses on the individual, more comprehensively covered bythe notion of “human development”.24 Emphasizing “growth with fairness”,Sen also stresses the need to ensure human security by creating scope forpolitical participation of the underprivileged, in addition to the achievementof economic and social security. Thus, human security and humandevelopment are linked in a way where the former is an end, and the lattera means. Both rely on the development of society. As Kaul states, humandevelopment and human security are the outcome of the sum total of ourdevelopmental activities—economic, social and political, as well as local,national and international.25 Specific areas identified as being closely linkedto human survival include poverty, the environment, health care, andhumanitarian assistance. Thus, educational development, technologytransfer and IT infrastructure combined with conservation of environmentare vital to the development of developing countries, thereby ensuring humansecurity. The actors for implementing the goal of security are no longermonopolized by the state; rather it includes non-state actors such as businesscorporations, international organizations, and NGOs. All these actors areto provide the necessary conditions for economic viability to each and everyindividual.

Sustainable Development

Sustainable development remains a contested concept in both thephilosophical and political senses. Its theoretical foundation is based oncontributions from ecology, economics, anthropology, sociology,psychology and politics. The concept of sustainable development dates backto the early 1970s, and the Club of Rome report, Limits to Growth, wasprobably the cornerstone piece of literature that contained a powerfulmessage about the impending environmental disaster in the world.26 TheUnited Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro (1992) is seen as the majorevent that organized coordinated efforts to focus on sustainable development.The international political salience of environmental issues arising fromaccelerating rates of environmental degradation, improved scientificknowledge and ecological imbalances facing humanity captures the

28 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

intellectual attention of thinkers and practitioners. In particular, the growth-based neo-liberal development paradigm has been questioned for creatingso much trouble with the environment. Melinda Kane states, “The field ofeconomics is perhaps most guilty of considering only its own scope ofactivity, assuming other layers (social, ethical, cultural) will operate by thesame rules because actors will always be rational in their decision making.”27

There are at least three different perspectives behind theconceptualization of sustainable development. First, most commonly,environmentalists perceive sustainable development as referring to thechallenge of taking environmental values, and incorporating them into thetraditional social and economic values that govern public policy and ourdaily behaviour. They emphasize the ecological sustainability of the worldwe live in. They argue that massive industrial growth and exponential riseof population are the root causes of most environmental degradation. Theworld economy, fuel consumption, industrial activities and energyconsumption have increased by as much as 20, 30, 50, and 80 timesrespectively during the last hundred years.28 So, according to this view,sustainable development is defined as development that meets the needs ofthe present generation without compromising the ability of futuregenerations to meet their own needs. Second, the economists’ view, oftentermed as the “growth is necessary school of thought”, highlights thenecessity of economic growth with fairness. They criticize theenvironmentalists for being obsessed with environmental values that ignorethe issue of prosperity for the current generations. They prefer to call it“sustainable economic development” by maintaining a balance betweeninvestment and the distribution of income (issue of per capita income).Finally, according to the advocates of human development, it focuses onpoverty and population. They argue that there are close links betweenpoverty, environmental degradation, and rapid population growth.29 Bysustainable development, it refers to the qualititative change in the humancondition by improving the basic indicators such education, health, foodand shelter. Despite differences in these views, there is consensus on oneissue: that the earth is endangered.

Each of the perspectives reveals a limited understanding of the reality.It also generates a dilemma of “sustainability” and “prosperity”. The issueof improving the standard of living must get due consideration in the wholegamut of the sustainable development debate. This requires striking abalance between the needs of economic prosperity and protecting theenvironment that will lead to crafting a policy to make prudent use of theearth’s resources, as well as an improvement in the quality of the

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 29

environment. Thus, arresting the central thrusts of these views, we mayargue that there are three broad components of sustainable development—environment, economic growth and population. So, we perceive sustainabledevelopment as a multidimensional concept, a pattern of development thatmaintains the integrity and long-term viability of the biosphere, but alsothat which is sustainable in economic, social, and political terms.30 It maybe noted that sustainable development has strong global dimensions bothbecause of the high levels of economic interdependence, and because offundamental concerns about the distribution of wealth, power and resourcesbetween North and South.31 The challenge for sustainability is to providefor those needs in ways that reduce negative impacts on the environment.But any changes made must also be socially acceptable and technically andeconomically feasible. It is not always easy to balance environmental, socialand economic priorities. Compromise and cooperation with the involvementof government, industry, academia and the environmental movement arerequired to achieve sustainability.

Conceptual Framework

The preceding theorization of the key variables clearly demonstratesthat globalization is closely interconnected with security in its changingfocus on the scope and agency of threat as well as with the constituents ofsustainable development. The whole process of interconnection is complexand complicated, with the involvement of intervening variables. While thetriangle of globalization–security–sustainable development represents acausal relationship, the security–sustainable development linkage is seenas an ends-means pattern (Fig. 3.2). Sustainable development is perceivedas an instrument to combat the threats to security, specifically in its humandimension. The relationship between globalization and MNCs is twofold,since one reinforces another. In a generic sense, the processes ofglobalization contribute to the ever-expanding role of FDI. On the otherhand, economic globalization itself is the outcome of internationalizationof production, capital and global trade.

30 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

Fig. 3.2 Triangular Relationship Between Globalization, Security andSustainable Development

Indeed, the processes of globalization have fundamentally changedthe way we think about security. This change may be conceived in terms ofboth agency and scope of threat. Non-state groups and individuals haveemerged as powerful agents of threat that have widened the scope ofsecurity.32 Thus, the concept of security embraces a broad-based, integratedapproach going beyond military orientation. A plethora of non-traditionalsources of threat manifested in economic, environmental and culturalspectrums constitutes the bedrock of security thinking in the present-dayworld. The spread of communication and Information Technology (IT),increased capabilities of drug smugglers and criminal organizations, identitycrises of disadvantaged nations and substate groups and aggravating globalpoverty are bound to exacerbate security concerns in any part of the world.Seen from this perspective, the operations of MNCs as agents ofglobalization have enormous implications for security.

Similarly, the scope of “sustainable development” has been deepenedand broadened in the age of globalization. Although the general awarenessabout environmental degradation was generated in the West in the 1970sthanks to green politics and grass-roots movements, it is only in the early1990s that it took a global dimension. A wide range of issues ranging fromenvironmental degradation and human development to income disparitieshas come to the centre stage of development thinking. Globalization oftrade and investment may be the most advanced form of social and politicaltransformation that increasingly influences land-use and land-cover changein different countries and regions, in part by changing government policyand offering economic incentives to farmers and land developers. More so,globalization has implications for environmental management capacities

Globalization

Security Sustainabledevelopment

MNCs

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 31

of states by restricting the public measures, on the one hand, by boostingthe influence of markets on social and economic outcomes, on the other.So, we may argue that the agenda of sustainable development must be linkedwith the process of globalization in order to achieve security anddevelopment goals at national or international levels.

Having conceptualized the triangular relationship betweenglobalization, security and sustainable development, we will explore thepossibility of partnership between MNCs and host governments in SouthAsia. A question may be raised as to why MNCs would be interested in thispartnership. Although sustainable development can be a common concernfor the two parties for its focus on the fundamental existence of the earth,the specific reasons may be to comply with legislation, to build betterstakeholder relationships, to acquire economic wealth and competitiveadvantage, and to maintain the ecological balance.

Fig. 3.3 Mutual Interdependence between MNCs and Host Countries

With this above-mentioned framework for analysis, we will examinethe cases of India and Bangladesh to illustrate how MNCs as the drivingforce of globalization and host countries of South Asia can develop mutuallybeneficial relations for sustainable development. Historically, both countriesfollowed relatively inward-looking public-sector dominated economicstrategies for decades. Financial and trade sectors were overregulated bythe imposition of several kinds of restrictions including licensing systemsand tariffs. India and Bangladesh started deregulating the industrial sectorin the mid-1980s, although the latter initiated an economic reforms processa bit earlier. The process of economic reforms received considerablemomentum in both countries in the early 1990s. Changes in the policyframework for attracting FDI are also almost similar. The incentive structure,regulations and organizational framework to facilitate FDI appear to bevery similar not only in these two countries, but also in the whole region. Itis true that because of the difference in the sizes of the economies of thetwo countries, there have been some variations while considering the detailsof policy and implementation. But the basic approach and policy responseto globalization of FDI are almost similar.

Globalization and FDI

The expansion of the role of MNCs through the mechanism of FDI in

MNCs Host countries

32 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

the world economy is the driving force behind globalization. As Janardhanstates, the engines that are driving the globalization process are MNCs.33

Financial liberalization enhances capital mobility. Human-capital formationin developing countries improves the conditions for FDI and for theproduction of manufactured goods and services in the South. Tradeliberalization, meanwhile, facilitates the exports of manufactured goodsand services. It influences a range of issues spanning financial liberalizationto ICT. Thus, firms increasingly have a choice of location, since transportand communications systems work smoothly and at continuously decreasingcosts. Simultaneously, governments are competing with each other to attractpotential investors by offerring tax breaks, infrastructure development, andoften also breaks in terms of environmental or social standards. However,the salience of FDI behind the process of globalization is widely recognized.As the World Investment Report 1997 states:

Foreign direct investment (FDI) continues to be a drivingforce of the globalisation process that characterizes the modernworld economy. With some $6.4 trillion in global sales in 1994(and estimated global sales of $7 trillion in 1995)—the valueof goods and services produced by some 280,000 foreignaffiliates—international production outweighs exports as thedominant mode of servicing foreign markets.

The establishment of the Bretton Woods financial system under USleadership in the post-War period facilitated the expansion of cross-bordercapital flows and trade through the operations of MNCs. The world is nowwitnessing a third-generation boom34 in FDI flows which began in 1995,setting a new record of around $350 billion in 1996, a 10 per cent increase.On the inflow side, 54 countries and 20 countries on the outflow side setnew records in 1996. The major feature of this boom is significantparticipation of developing countries on the inflow side, although it is drivenprimarily by investments originating in just two countries—the United Statesand United Kingdom. For example, among the world’s 44,000 parent firms,7,900 firms were based in developing countries in the mid-1990s, comparedto 3,800 in the late 1980s—exports continue to be the principal mode ofdelivering goods and services to foreign markets. The gross product offoreign affiliates, a measure of their output, almost tripled between 1982and 1994, and its share of world output increased slightly, from 5 per centin 1982 to 6 per cent in 1994. In developing countries, the output of foreignaffiliates has contributed (in 1994) more to gross domestic product than ithas in developed countries: 9 per cent compared to 5 per cent.35

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 33

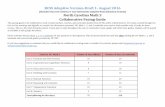

Table 3.1 Outflows of FDI from Five Major Home Countries

Home Country 1985 1987 1989 1990(US$ b) (US$ b) (US$ b) (US$ b)

France 2.2 9.2 19.4 34.8Germany 5.0 9.2 13.5 22.5Japan 6.4 19.5 44.2 48.1United Kingdom 11.1 31.1 32.0 21.5United States 8.9 28.0 26.5 29.0Total 33.7 97.1 135.6 155.9Developed countries 52.1 132.6 187.1 216.7Developing countries 1.2 2.4 8.9 8.1

Source: John Dunning, Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy,New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1993, p. 19.

Table 3.1 shows how FDI flows have expanded over the years, markinga big transformation observed in 1990. For example, FDI outflows ofdeveloped countries jumped from US$52.1 in 1985 to $216.7 billion,signifying a more than fourfold increase.

The deregulation and globalization of financial markets and capitalaccount liberalization (as part of structural adjustment programmessupported by the IMF and the World Bank) in developing countries coupledwith lower interest rates and institutionalization of savings in developedcountries are the main factors behind rapid transborder capital mobility.Transborder mobility has been further enhanced and strengthened by thegrowing understanding and nexus of the national elite of developingcountries with global players of finance capital. It is the globalization processwhich enriches and reinforces the nexus between the national elite andinternational finance capital. The globalization of production and trade,and internationalization of financial transactions are organized largely bythe fast-growing MNCs. It is estimated that multinationals today accountfor a quarter to a third of total world output, 70 per cent of the world trade,and 80 per cent of direct international investment.36 The expansion of FDIis closely linked to three major phenomena: internationalization ofproduction, increasing global trade and financial flows.

The 1980s and 1990s have witnessed rapid expansion of the productionprocess all over the world, facilitated by market-oriented policies in theNorth, structural adjustment programmes in the South, and technologicaladvancement in general. The World Bank, IMF and GATT (later WTO)

34 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

provided institutional support for this neo-liberal transformation. The drivingforce behind the internationalization of production is FDI. Faced withstagnant demand and sharp rise in production costs in home countries, MNCsare shifting their production bases to foreign countries, where the domesticmarkets of goods and services are growing and production costs are muchlower, as raw materials and labour are very cheap. Second, there has beenan unprecedented growth of international trade—almost thirtyfold in thelast three decades—as a result of dramatic rise in global production.Although world trade is still concentrated among the industrialized countriesof the North—its share is more than 80 per cent—there has been spectacularincrease in South’s manufacturing exports to the North, indicating aglobalized pattern in global trade. Finally, the process of globalization offinance has assumed greater significance and power than that of production,specially in recent years. The volume and mobility of global finance capitalhas surprised many observers. In 1986, about $188 billion passed throughthe hands of currency traders in New York, London and Tokyo every day.By 1995, the daily turnover reached almost US$1.2 trillion.37 Historically,most trading in foreign exchange was the result of international trade, asbuyers and sellers of foreign goods and services needed another currencyto settle their transactions. But now, trade in currency has very little to dowith international trade, which accounts for just 2 per cent of global currencymovements. Added to currency trade, new financial instruments such asbonds, mutual funds, junk bonds, and derivatives have emerged in the recentpast, which have further contributed to the globalization of finance. Allthese form the bedrock of economic globalization stimulated by FDI.

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 35

IV

Implications of Globalization:A Critical Overview

Despite the prospects of benefits (as many argue), the process ofglobalization has unleashed a number of negative implications for nationstates (particularly those of the developing world) in many different ways.As a result, most developing countries, more specifically LDCs, arestruggling to cope with the new conditions in the global politico-economicarena. In identifying which the beneficiaries of globalization are, the UNDP-sponsored Human Development Report 2000 reveals that it is financialdealers, MNCs, tourists and highly-skilled labour who will be benefittedfrom the globalized world. Although it is identified as a group of people, itcould easily be inferred where those are people living. Even this concern ofexcluding the vast majority of people from the basket of benefits also reflectsin the deliberations of the G-7 summit.38 Though considered in the contextof industrialized countries, Rodrik’s observation reflects a verbatim picturein the South:

The cumulative consequence of globalisation will be thesolidifying of a new set of class divisions – between thosewho prosper in the globalized economy and those who do not,between those who share its values and those who would rathernot, and between those who can diversify away its risks andthose who cannot.39

Having seen the above, let us identify the specific areas ofimplications. First, the process of globalization exacerbates the existingpoverty and inequality situation within and among countries. It is oftenpointed out that globalization accounts for rising inequality in society.Charles Oman maintains that globalization today is accompanied by growinginequality, both within and between countries, and by a threat of exclusionfaced by many people.40 Some argue that globalization and liberalizationare precipitating a large-scale marginalization process. Historically, asWilliamson maintains, the inequality trends which globalization producedare at least partly responsible for the inter-war retreat from globalization[which appeared] first in the rich industrial partners.41 The situation becomesmore terrible in the South when this rising inequality conjoins with massive

36 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

poverty. Moreover, the issue of inequality also involves the functioning ofmultilateral organizations like the WB, IMF and WTO, which are maintainedthrough inequality and the will of their powerful members.42

Second, the issue of state autonomy figures prominently inunderstanding the political and economic implications of globalization. Stateautonomy is viewed as a situation at one end of the continuum in whichnational governments make decisions with little or no consultation and noexplicit cooperation.43 The process of globalization has enormous impacton the capacity of a state in exercising its autonomous power. Globalistspronounce the end of national economies, of geography and of the stateitself resulting from the growing transnational integration and rising powerof the market. Some hold to the view that, in conditions of globalization, itis precisely the state’s capacity to act strategically that has been eroded.44

Others insist that the state retains this capacity because of its location at theinterface between the international and the national.45 The reality is thatthe idea of a fully autonomous state is a problematic. The state is poised tomaintain a complex interplay between the civil society (inwards) and thecommunity of states (outwards). External sources of strength can buttressstates that are weak internally, but may also encourage them to pursuecoercive policies that weaken them further. Holsti dubbed it the “state-strength dilemma”.46 There are two extremes in this autonomy question—the state’s separateness from society, and its closeness to society.Globalization might destabilize states in the South, as it would expose theinternal problems and perennial tensions between state and society. In thecase of some of the weakest states of the South, strength may be generatedfrom social institutions within states in the absence of effective domesticsources of sustenance. State strength may be derived from the intensifiedintegration and interactions with external forces, particularly the weak andsmall states. But this is a remote possibility in the South. The issue thatfigures prominently in this part of the world is the weakening of the statesyndromes in the face of losing control over increasing pressures from withinand outside the state. External pressures have already curtailed the autonomyof the state in the South.

Third, it is well recognized that the process of globalization has beengenerating tensions on the fault lines of social integration. This tension isobserved between markets vs stability on the one hand, and betweenuniversalism vs particularism in the social context on the other. Thisphenomenon is common to both North and South. Economically, the processthat has come to be called “globalization” is exposing a deep fault linebetween groups which have the skills and mobility to flourish in global

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 37

markets, and those who either don’t have these advantages or perceive theexpansion of unregulated markets as inimical to social stability and deeply-held norms. The result is severe tension between the market and socialgroups such as workers, pensioners and environmentalists, withgovernments stuck in the middle.47

As to the tension between universalism and particularism, FrancisFukuyama’s “end of history” thesis as a universalization of liberal marketideology, along with the globalization of multinational capitalism, markedthe dissolution of differences into sameness: an emergence of culturalhomogenization. On the other hand, particularistic conflictualities,nationalist or ethnic, began to dictate the mode of articulation of politicalpractices and ideological/discursive forms in global relations, that is, culturalheterogenization.48 Arjun Appadurai suggested in this context that “thecentral problem of today’s global interactions is the tension between culturalhomogenization and cultural heterogenization”.49 However, it would be amistake if we take a position of “presentism” to celebrate the process ofglobalization as a new epoch which marks the end of the old,50 becauseglobalization is characterized by contradictions between the universal andthe particular, and despite the promise of radical changes by the process ofglobalization, one cannot ignore “continuities”, as unequality andunderdevelopment on the world scale remains as a function of globalcapitalism. It raises the question as to how this tension generated. Rodrik(1994) suggests that there are three sources of tension, particularly on theeconomic front. One, reduced barriers to trade and investment accentuatethe asymmetry between groups that can cross international borders andthose which cannot. In the first category are owners of capital, highly-skilledworkers and many professionals, while the second category is that of theunskilled and semiskilled. Two, globalization engenders conflicts withinand between nations over domestic norms and social institutions that embodythem. Spread of globalization creates opportunities for trade betweencountries at very different levels of development. Three, globalization hasmade it exceedingly difficult for governments to provide social insurance.The welfare state has been further attacked.

Fourth, the process of globalization has enormous implications forlabour rights in domestic and international contexts. Neo-liberals argue thatglobalization has a positive relationship between trade and employmentopportunities. The fear that greater openness is creating severe adjustmentproblems for certain countries, and for particular groups within countries—such as unskilled workers—became a topic for discussion in the 1999 WorldEconomic Forum Meeting held in Davos, Switzerland, with the theme

38 Arjun Bhardwaj / Delwar Hossain

“Globalization with a human face”.51 But it is mainly the developedcountries which benefit from this situation. Conventional wisdom says thatincreasing trade facilities could expand the labour markets of the developingcountries to the rich nations. But the paradox is that the developing countriesare surplus of unskilled labour, and there have been strict restrictions onimmigration in the industrialized countries, creating asymmetry betweenmobile capital (physical and human) and immobile “natural” labour. Underglobalization, the rich countries anticipate reduction in the number ofunskilled labourers from developing countries, causing adverse affects fortheir economies (though empirical studies suggest that international tradehas had only limited impact on wages).52 Another dimension of the trade-labour linkage is tension between trade and domestic social arrangements.International trade creates arbitrage in the markets for goods, services, labourand capital. But trade often exerts pressure on another kind of arbitrage aswell: arbitrage in national norms and social institutions. For instance, childlabour in international trade causes strain as it reflects on how trade meldsor otherwise with domestic norms and institutions.53 Workers experiencedifficulties in a globalized economy. The political salience of labour’s voiceis currently muted for three reasons. One, the same pressures that reducethe bargaining power of labour in the workplace also reduce its power inthe political marketplace. “Competitiveness” becomes another term forlabour costs. Two, the negligence of political parties in the domestic contextalso hampers their interests. Three, the receptivity of the general public tothe ideas of labour advocates is quite low.54

Fifth, globalization also raises security concerns in many different ways,such as increasing tensions, instability and sense of insecurity of nations,societies and individuals through increasing the propensity of intervention,resurgence of ethnic groups and communal feelings, poverty andmarginalization, replacement of traditional but stable value systems,proliferation of small arms, a fast-degrading resource base andenvironment.55 Although in the context of India, Chari deserves mentionhere.

The liberalization and globalisation policies currentlybeing pursued by India unleashed enormous economic andsocial forces that have greatly heightened expectations in thepeople. Their growing impatience with delays in improvingthe quality of their lives lends a new urgency to dealing withthese newer sources of insecurity. Otherwise, impatiencewould promote frustrations and lead on to violence.56

Moreover, globalization facilitates international crime by unleashing

Globalization and Multinational Corporations in South Asia 39