Racialised postsocialist governance in Romania s urban...

Transcript of Racialised postsocialist governance in Romania s urban...

-

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttps://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccit20

Cityanalysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action

ISSN: 1360-4813 (Print) 1470-3629 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccit20

Racialised postsocialist governance in Romania’surban marginsHousing and local policymaking in Ferentari, Bucharest

Dominic Teodorescu

To cite this article: Dominic Teodorescu (2019) Racialised postsocialist governance in Romania’surban margins, City, 23:6, 714-731, DOI: 10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208

© 2020 The Author(s). Published by InformaUK Limited, trading as Taylor & FrancisGroup

Published online: 06 Feb 2020.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 178

View related articles

View Crossmark data

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccit20https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccit20https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208https://www.tandfonline.com/action/authorSubmission?journalCode=ccit20&show=instructionshttps://www.tandfonline.com/action/authorSubmission?journalCode=ccit20&show=instructionshttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/mlt/10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/mlt/10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2020-02-06http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2020-02-06

-

Racialised postsocialistgovernance in Romania’s urbanmarginsHousing and local policymaking inFerentari, Bucharest

Dominic Teodorescu

Postsocialist urban development is partially characterised by housing deterioration and theperpetual overrepresentation of Romanian Roma in substandard dwellings. These phenom-ena are particularly noticeable in the margins of larger Romanian cities. Many poor Roma-nians found, in urban peripheries, a last resort during a period of economic crisis and housingshortages. In the meantime, public policy and urban planning have focused on maintaining‘collective order’ and accommodating the wishes of the ‘decently’ housed residents of thecity. This is certainly the case in Bucharest, where squatters and homeless people havebeen expelled from central districts and where the same privileged districts receive substan-tially more attention. This collective order is apparently deemed more important than theneeds of marginalised groups in Romanian society. This article examines how urban mar-ginality is addressed at the municipal level and how ‘parsimonious’ public intervention inpoor residential areas is justified. In doing so, I highlight the roles of postsocialist devolution,inadequate use of EU and national funds, and reviving racialisation in reproducing housingpoverty.

Key words: governance, local trap, affordable housing, inequality, racialisation, Bucharest,Romanian Roma

Introduction

Over the past three decades, Roma-nian politics and governance havebeen reconfigured dramatically.

The centrally-led socialist plannedeconomy was replaced by a decentralisedand market-oriented model. Decentralisa-tion of authority was one of the conditionsof the European Union (EU) for Romania’s

accession (Dobre 2010; Ion 2014; Profiroiu,Profiroiu, and Szabo 2017). Decentralisa-tion was conflated with financial and politi-cal autonomy and more citizenparticipation. However, the devolution ofauthority has also meant that most socioe-conomic challenges fell under the responsi-bility of local administrations. In return forthese thoroughgoing reforms, the EUpromised generous funding that would

# 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis GroupThis is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivativesLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproductionin any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

CITY, 2019VOL. 23, NO. 6, 714–731, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8287-2213http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/http://www.tandfonline.comhttp://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1080/13604813.2020.1717208&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2020-02-19

-

finance locally expressed needs. In practice,however, the situation has proven to bemuch less tractable (Clapp 2017; Profiroiu,Profiroiu, and Szabo 2017; Vincze andZamfir 2019).

I focus on the decentralised governanceof one of Bucharest’s administrative sub-units, Sector 51 and aim to understandwhat role governing institutions inBucharest play in the reproduction or miti-gation of housing decay and severe socioe-conomic deprivation. Sector 5 containsFerentari (see Figure 1), a notorious neigh-bourhood with a disproportionately highpresence of Romanian Roma.2 The

neighbourhood exhibits severe social, tech-nical, and economic difficulties. These issuescould and should be eligible for EU Cohe-sion Policy funds or Romania’s own devel-opment funds, but are largely overlookedby local politicians, who are responsiblefor applying for grants-in-aid. Moreover,urban displacement and ‘Romaphobia’has further pushed poor Roma to theurban margins in recent years (Lancione2017; O’Neill 2010; Vincze 2018; van Baar2018).

Racial and socioeconomic segregationworsened in Romania after the fall ofstate socialism (Berescu, Petrović, and

Figure 1 Map of Bucharest (Source: original map by author).

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 715

-

Teller 2013; Powell and Lever 2017; Vinczeand Zamfir 2019), with over 25% of allRomanians living in poverty (INS 2016)and Roma representing up to 50% of thepopulation in deprived neighbourhoods(Vincze 2018). This situation can be par-tially explained by understanding the inca-pacity of local authorities and their apathyin absorbing available EU or national funds(Ion 2014) as creating a ‘local trap’ of decen-tralisation. Although governance anddecentralisation in Romania are increas-ingly subjects of scholarly interest, norecent works have used the local trapconcept in problematising local decision-making. According to Mark Purcell (2006,1921), the local trap is ‘the tendency toassume that the local scale is preferable toother scales’, because local decision-making supposedly reflects local, democra-tically-informed desires and requirements.But who informs these desires? Is it theelectorate or rather local coalitions ofprivate and public actors? For Purcell(2006, 1921), this remains highly uncertain,and local decision-making gives no guaran-tee of increased popular participation, as‘all depends on the agenda of those empow-ered’. By considering the case of Bucharestand the local-level actions there, this articlesupports the argument that the local scaleis not a priori the best scale for producinggood outcomes. Moreover, it also arguesthat racialised discourses at the localadministrative level can only increase thehazards of the local trap.

I analyse the Bucharest’s housing govern-ance in poor districts through two sets ofdata: interviews and document analysis.Through the interviews with officials, Iattempted to obtain information about howsubstandard housing, external developmentfunds and existing policies, and the situationof Bucharest’s poor are understood. Theselected official documents are analysed inorder to establish what the existing socialhousing policies are and what is proposed todesegregate Bucharest and increase the city’snumber of affordable housing. The fieldwork

took place in three periods: November 2011–March 2012, March 2014, and June–Septem-ber 2015. The local housing and governancesituation of Ferentari and Sector 5 was dis-cussed with a total of fourteen informants.Of these, five were officials from Sector 5and two were planners from Bucharest cityhall.3 The informants from Sector 5 wereactive in the domains of housing, planning,public works, and racism and equal rights.

In total, I conducted 12 face-to-face inter-views with these officials, interviewing onecity hall planner four times and conductingfollow-up interviews with two officialsfrom Sector 5. These seven state officials4

did not respond to my email and phone invi-tations, but were recruited through happen-stance. Even when visiting the city hall andthe Sector 5 office, I was repeatedlyignored. It was through an unplannedencounter with someone from Sector 5 thatI gained access. This person also initiated asnowball effect by putting me in touch withother officials from Sector 5, only five ofwhom ultimately accepted my invitation toparticipate. My academic background raisedsuspicions, while race- and poverty-relatedquestions often resulted in lack of interest infurther cooperation.

Furthermore, I held two interviews with theFrench diplomat Jérôme Richard, serving as acoordinator of Sector 5’s master plan for Fer-entari, and two with Petre Florin Manole,Romania’s secretary for the national minoritycommission and a Roma himself. All inter-views were semi-structured and, as requestedby some informants, anonymity was provided.I also interviewed five experts in housingexclusion (i.e. Cătălin Berescu, LiviuChelcea, Florina Presada, Anemari Necsu-lescu, and Florin Botonogu) who shared criti-cal reflections on the actual state of affairs andhelped me analyse the gathered data.

In addition, I analysed: (1) Bucharest’sGeneral Urban Plan, Plan UrbanisticGeneral (PUG); (2) a master plan for thecohesive future urban development in thecity, Strategic Concept Bucharest 2035,Concept Strategic Bucureşti 2035 (CSB);

716 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

-

(3) Sector 5’s latest master plan, RegenerareUrbană Ferentari (RUF; Sector 5 2017);(4) social housing allocation procedures; and(5) an internal housing project from Sector 5.The analysis of Ferentari’s housing and socio-economic policies is primarily based on tran-scribed interviews, official documents, andsocial housing allocation procedures.

In what follows, I first ‘set the stage’ for thearticle’s theoretical framework by analysing aselection of remarkable quotes from oneinterviewed official. In the remainder of thesection, I describe how a local trap wascreated in Romania’s Europeanisation anddecentralisation processes, which involvedthe problematic pairing of centralisedfunding decisions and local decentralisedsocioeconomic policymaking. Second, Idiscuss the literature on the racialisation ofBucharest’s poor and their ongoing displace-ment from central areas. Third, by drawingon empirical data and local policy documents,this paper illustrates how local, everydaypolitics has unfolded and failed to addresssocioeconomic and housing problematics.While arguing that the ill-prepared decentra-lised governance structure of Bucharest hasplayed a major role in reproducing poverty,I also comment on the racist sentiments thathave further frustrated the implementationof inclusive policies.

Local governance, postsocialist citizenshipand marginalising the poor

In March 2014, I first interviewed a publicworks official from Sector 5. A selection ofhis thoughts on Sector 5 in general and Feren-tari in particular sets the stage for the literatureto be discussed. When I first brought up thetopic of ‘good governance’, he responded thathis district was ‘probably leading in thecountry’, and continued to state that thesector ‘made schools, kindergartens . . . parks. . . in the poor areas of the sector . . . 99% ofall streets are connected to the sewer system,all paved’. Furthermore, the official stressed

that citizens were fully responsible for theirliving conditions. Even the serious issues ofdrug use, flooded cellars of apartment blocks,rat infestations, and the severe dilapidation ofbuildings in the sector’s poorest areas weredeemed private concerns, matters to beaddressed by local residents or by strict poli-cing. Essentially, he underscored a narrowunderstanding of local governance in hissector that can be summarised as follows: theinvestments in local well-being and economicsustainability serve above all the ‘car-owning,tax-paying, and hard-working’ Romanian,while welfare support is kept at an insignificantlevel. When I tried to find out whether anyefforts were really being made to constructmuch-needed public housing (he was after alla member of the Romanian Social DemocraticParty), the conversation suddenly changedtrack. An extensive, disdainful account ofpoor Bucharesters followed, characterised bydistrust, contempt, and hatred:

‘Let’s be honest here, didn’t we give them[i.e., the poor Bucharesters from Sector 5]these “vagabond” apartments on Livezilor,Zăbrăuţilor, and Carpaţi? We connected themto water, we cleaned the buildings, we did Idon’t know what else . . . A kindergarten wasbuilt. But these people need to be adopted,and this is what the EU doesn’t understand.The EU is reacting like a freaked-out woman,and instead of adopting these people, tochange them, to give them livelihoods [inricher parts of the Union], they provide theseinclusion funds. Their reaction is like a guywho gives money to his hysterical wife, just sohe can be left alone.’

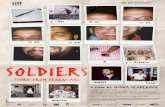

Apart from the blatant sexism embedded inthis statement, this moment of the interviewwas vital because it revealed four things.First, I identified a cruel lack of interest ininclusive politics. Second, even though heframed ‘giving’ communist-era one-room orvagabond apartments (see Figure 2) asutterly generous, the reality is that these apart-ments were from the beginning publichousing estates. While the bulk of Romania’ssocialist-era public housing was privatised in

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 717

-

the first postsocialist years (Amann, Bejan,and Mundt 2013; Berescu, Petrović, andTeller 2013; Şoaită 2017), a small percentageof mostly inferior housing units stayed inpublic hands, becoming a ‘magnet’ to poorRomanians (Marcińczak et al. 2014). Third,his assumption that the sector connected‘them’ to water is curious to say the least, asmost of the physical infrastructure wasalready in place before 1989 (Chelcea andPulay 2015) and severely deteriorated in thepostsocialist years because of public disinvest-ment. Fourth, that moment of the interviewwas also the beginning of an explicitly racistdiscourse that went further than the infantilis-ing declaration that ‘these people need to beadopted’. More specifically, he spoke nolonger about poor residents (amărâţi) butabout Gypsies (ţigani), and ‘clarified’ that itwas preferable if they left his sector, in linewith what former president Traian Băsescuhad hoped for during his term as Mayor ofBucharest (Creţan and Powell 2018):

‘Everywhere in the world, you encounterpoor settlements, but in most cases peopleprove to be inventive, you understand? Butmy impression of Gypsies is that, whereverthey settle, the fields are parched. If you’dreturn after two years to an abandonedsettlement, it’d be a miracle if anything wasactually growing where they pitched theircamp. Not sure how, don’t know what theydo, but there must be acid in their urine.Wherever they stop, they raze everything tothe ground. I talk about the Gypsies that arenot Romanianised . . . old habits persist and Iam happy to see them leaving Romania.Because before they left, some ten years ago,they robbed us, they harassed our women –they grabbed purses out of their hands, [but]now they rob yours, you understand?’(March, 2014)

In the remainder of this section, I reviewtheory that critically reflects on the devolu-tion of authority in general and in Romaniain particular. This clarifies how decentralisedgovernance certainly does not equal increased

Figure 2 The so-called ‘vagabond’ apartments on Livezilor Alley (Source: author).

718 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

-

democracy and attention for inclusivepolicies.

Bucharest’s local trap: from top-downplanning to badly managed governance

Bucharest’s spatial development is increas-ingly dictated by global capital investment(Nae and Turnock 2011), with local budgetsbeing streamlined to sustain this process5

(Ion 2014; Light and Young 2015). The litera-ture usually refers to streamlining as theprocess by which elected governing bodiesbecome less influential over the patterns ofurban development and less accountable tothe electorate (Goodwin and Painter 1996;Purcell 2006). Streamlining can further betraced back to reduced taxes, increased—and yet selective—public infrastructurespending, the privatisation of municipalinfrastructure, and the relaxing of planningpermitting (e.g. Geddes 2005; Jessop 2005;Jessop, Brenner, and Jones 2008). This shiftto streamlined governance did not startimmediately after 1989. The first postsocialistdecade was chaotic, during which the lack offinancial resources reduced the role of thelocal governments to ‘the delivery of basicservices, the reviewing of permit applications,the granting of zoning variances and the per-mitting of a patchwork of small- andmedium-sized private building projects’(Ion 2014, 177). From the late 2000s,increased investments from EU and nationalfunds changed this situation. However, thenew financial opportunities did not result inincreased social expenditures. Local govern-ments were instead active in financing, forexample, renovation works, flagship projects(e.g. a new national stadium or the People’sSalvation Cathedral), and major infrastruc-tural projects. An in-depth discussion ofthese urban developments and streamliningis beyond the scope of this paper; instead, Ifocus in the remainder of this section onhow the imposed devolution is potentially alocal trap due to the dismissal of localclaims in governance.

According to Mark Purcell (2002, 2006,2013), an urban democratic crisis canemanate from the assumption that devolveddecision-making equals increased publiccontrol. This assumption implies that localgovernance decreases the gap betweenelected representatives and the electorate.Local governance or ‘the local’ is thus ‘con-flated with the good’ and becomes a politicalend in itself, rather than ‘a means to an endsuch as democracy, justice or sustainability’(Purcell 2006, 1927). However, the transferof administrative responsibilities from thenational to local levels can risk reducingaccess to social services if local budgets areinsufficiently bolstered. This problem canmanifest itself in two ways. On one hand,the local can simply be a suboptimal scale atwhich to carry out complex tasks. Certainpolitical interventions or certain contextssimply require different scalar arrangements,which are hard to establish a priori. Second,decentralisation can potentially marginalisethe needs and rights of minority groups.Despite these being expressed, the majorityof the electorate can silence these minoritiesby an overly narrow interpretation of urbandemocracy (Attoh 2011). Purcell does notentirely reject the local as a political scalefor increased democracy, but he rejects theuncritical acceptance of devolved responsi-bilities that potentially undermine socialjustice.

In Romania’s case, the country underwentrigorous decentralisation during the 1990s inorder to start the European integrationprocess and become eligible for EU funds(Dobre 2010; Ion 2014; Profiroiu, Profiroiu,and Szabo 2017). At the same time, fund-granting decisions became increasingly‘regionalised’. Romania has opted for‘regional operational programmes’ that arecreated and administered by developmentregions.6 Through these programmes, localadministrations are expected to (1) identifywhere people are at risk of poverty and exclu-sion and (2) submit application proposals forthe EU’s structural and regional developmentfunds. Subsequently, the development region

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 719

-

is responsible for selecting funding appli-cations and redistributing granted funds.The pervasive problems flowing from thisapproach can be captured in two develop-ments. First, local politicians clearly favour‘fast-track, large-scale’ infrastructural pro-jects and city beautification programmes asa way to gain political capital among theirelectorate (Ion 2014; Marin and Chelcea2018). Second, the political affiliations oflocal recipients are often of overriding impor-tance, and funds are seen by state officials as a‘vehicle for the extraction, instead of theredistribution, of public resources’ (Ion2014, 172). Consequently, the use of nationaland EU funds is narrow (i.e. for infrastruc-ture and beautification), leaving many vitaland much-needed tasks, such as housingrenovation and construction, unaddressed.Ample reason exists to question the effective-ness of Romania’s decentralisation process inreducing the gap between ‘local needs’ andactual policy outcomes.

The initial low absorption of EU andnational funds and the subsequent urgencyof increasing the use of allocated publicfunds have resulted in an increase in thenumber of ‘fast-track’ infrastructural andbeautification projects (Ion 2014; Tosics2016). This recent phenomenon has exposedthe inability of local administrations inRomania to counter social polarisation withavailable public funds. Instead, projectsapproved in Bucharest have disregardedpoorer parts of the city (Ion 2014; Surubaru2017), destroyed cultural heritage (Calciu2016), and stimulated car use in an alreadycongested city (Chelcea and Iancu 2015; Ion2014).

The above examples illustrate how devel-opment proposals originating from thedrawing boards of local administrations donot necessarily consider the needs anddesires of local inhabitants. This is not tosay that the local level cannot be radicallychanged by effective resistance or citizen par-ticipation, but rather illustrates that in theBucharest context, neoliberal urbanismprevails.

Governing Bucharest’s poor citizens: someexamples of displacement practices

On top of the issues involving devolution,poor Bucharesters are also being actively dis-placed by the city’s governments. I followhere Vincze and Zamfir (2019) who arguethat much of the displacement politics inRomania are closely linked to spatial raciali-sation of the poor and the (often informaland substandard) settlements they inhabit.They argue that spatial racialisation enablesauthorities to ‘easily’ displace ‘the poor, theRoma [from] the spaces where they live’ inorder ‘to increase their [the space’s] value’(2019, 445). Studies of evictions (Arpagianand Aitken 2018; Lancione 2017; Vinczeand Zamfir 2019), gentrification (Chelcea,Popescu, and Cristea 2015), the policing ofunwanted poor in central districts (Chelceaand Iancu 2015; O’Neill 2014, 2017; Vinczeand Zamfir 2019), and the removal of illegalsettlements (Lancione 2017; StudioBASAR2010; Vincze and Zamfir 2019) haveexposed some aspects of how the city andsector councils endeavour to move peopleaway from squats, sidewalks, and centralareas.

However, there are different interpret-ations of the local management of poorBucharesters. Michele Lancione (2017, 2019)has described, for example, the active banish-ment of an evicted Roma community thattried to resist eviction by camping in frontof their former dwellings. He argued thatwithin the overarching processes of the capi-talist system, local politics further shape pre-carity. In particular, the violent reactions tore-squatting, the occupation of public space,and demonstrations reveal for Lancione aclear political choice: one engages construc-tively with deepened precarity or otherwisefaces relentless violence.

Bruce O’Neill instead highlights the soph-isticated politics of the domination and sub-jugation of poor and jobless Bucharesters.In his works (2010, 2014, 2017), O’Neill hasfollowed a group of what he calls ‘idle’,‘bored’, and ‘invisible’ Bucharesters. His

720 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

-

ethnographic engagements with this groupreveal a different interpretation of the displa-cement policies targeting Bucharest’s mostprecarious groups. Instead of arguing thatthe activities and lifestyles of these impover-ished people are ‘unrecognised social pro-duction’ or ‘radical contestations’, heidentifies disguised forms of inhabiting thatare intended to stay outside the institutionalgaze (O’Neill 2017). Daily practices such asconsuming, working, and dwelling areexperienced by these poor Bucharesters asprofoundly insignificant. Squatting, forexample, is described as the art of not attract-ing the attention of the municipality or neigh-bours. This is achieved by making as littlenoise as possible and being home only atstrictly necessary times of day. The labouractivities of these marginal poor (mostlyhelping car drivers finding free spots) aremarked by high stress levels due to a dailyhide-and-seek with patrolling policemen, andthe purchase of groceries takes place in smalland unpretentious booths, as these people aredenied access to regular supermarkets.Hence, seen from this perspective, precarityis not necessarily banished to more peripheralspaces but continues through humiliatingrhythms outside the institutional gaze.

The situation in Ferentari

Ferentari takes a somehow unique place inBucharest. It contains the highest concen-trations of Bucharest’s most deprived commu-nities and it is indeed also the place wheremany Bucharesters affected by the policiesdescribed above found a last resort. Althoughthe actual number of impoverished Buchares-ters inhabiting Ferentari is difficult to deter-mine, estimates range from 12,000 to 40,000(Teodorescu 2018; Sector 5 2017). Thesepeople live concentrated in the south of theneighbourhood, the area also often called theghetto (ghetou), ‘the Bronx’ (Bronxul), or‘Gypsy land’ (ţigănie). Gergó́ Pulay (2015) isright when he claims that an imaginary con-tainer was placed in Ferentari, filled with all

the prejudices of majority society regardingsocio–ethnically deprived areas—‘an internalOrient’, to paraphrase Edward Said. Imminentevictions are a smouldering threat here.However, in Ferentari, one can also see howa complex assemblage of informal economicactivities animates hopes of improved livingstandards (Teodorescu 2018; Pulay 2015).Many apartments are used as workplaceswhere, for example, shoes and grave wreathsare manufactured, hair is cut for a fair price,and groceries can be bought on credit (cum-părături pe caiet).

Beyond this in situ entrepreneurship, Fer-entari also hosts numerous flower ware-houses, scrap recycling companies, andthriving networks of more obscurebusinesses. Pulay (2015, 130) accuratelysuggested that ‘the neighbourhood can beunderstood as an extremely busy intersectionbetween diverse local and transnational net-works’. Nonetheless, this pauperised popu-lation’s urgent needs and critical housingsituation are obvious. In the remainder ofthis article, I examine how these are under-stood and addressed by the local authorities.

Actual and future housing inclusionefforts: does it work and for whom shouldit work?

Analysis of my data identifies three distinctbut related policy issues. First, the actualsocial housing provision in Bucharest is dis-cussed. Second, I provide an overview ofsome policy plans that have been presentedin recent years. At least on paper, these areintended to increase the number of socialhousing units and to improve the overallliving conditions in Bucharest. Third, Isituate local governance within a discussionof racism and political disregard for poorBucharesters. Arguably, this section illus-trates how unclear social housing rules, insuf-ficient labour and know-how, scarce financialresources, and racist attitudes among localofficials thwart effective housing policyimplementation.

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 721

-

While this article offers a case study oflocal governance practices in administrativeunits with high Roma segregation, this doesnot mean that a poor Bucharester is necess-arily a Romanian Roma. Poverty and exclu-sion are, however, heavily racialised inRomania (Creţan and Powell 2018; Csepeliand Simon 2004; Vincze and Rat 2013;Vincze and Zamfir 2019). According toRughiniş (2010), the racialisation of poorplaces results in the ‘hetero-attribution ofethnicity’ by officials to local residents, i.e.the ascription of ethnicity to an individual orcommunity by Romanian officials based on aset of racialised stereotypes. For example,several residents I spoke with in Ferentaridid not identify as Roma or said they werehalf-Roma, half-Romanian. Interviewed offi-cials, on various occasions described Feren-tari’s population as ‘Gypsies’ (ţigani) or‘people of colour’ (oameni de culoare) onlybecause they resided in the Sector’s poorestparts (the ‘Gypsy land’).

Existing social housing policies in Ferentari

The official introduced above mentioned thathis sector ‘really insisted’ on offering betterconditions to its impoverished residents.The experience of residents and my findingsindicate the opposite. Romania became a‘super homeownership society’ after 1989through government decree No. 61/1990.By that decree, privatised state-built, social-ist-era dwellings were offered at low pricesto sitting tenants supported by advantageousloans—a so-called giveaway privatisation. Asa result, the proportion of social housingunits dropped to 2% at the national leveland just below 1% in Bucharest (RomanianStatistics Institute, INS). In addition, thenew National Housing Agency, AgenţiaNaţională pentru Locuinţe (ANL),7 foundedin 1998, did not meet the EU requirementsto build 100,000 new units per year (Amannet al. 2013). In Ferentari, the little remainingsocial housing is concentrated in small one-room apartment blocks from the 1960s (the

earlier mentioned ‘vagabond apartments’).The few newly built ANL social housingestates are far from Ferentari and mostlyoutside Sector 5. That is a problem, becausesome ANL dwellings are only available toSector-residents. Furthermore, tenancyrequirements are stringent. For example,one must prove that one has not previouslyowned a dwelling, as ANL dwellings are pri-marily intended to provide housing forgroups that could not benefit from thelarge-scale housing privatisation of the early1990s. One of the planners from city hallclarified this issue:

‘Of course, social housing or municipalhousing companies are nonexistent and plansto build new houses for people living ininadequate dwellings do not exist, either. Notin a concrete sense, at least. Sure, there is theANL, but that agency sets unrealistic goalsand building criteria, which clearly do notcorrespond to the needs of such people.’(Official A, March 2014)

I was intrigued by the words ‘such people’ and‘unrealistic criteria’. The planner reasoned thatthe high prices and exclusive locations of mostANL projects make new social housing unaf-fordable for poor Bucharesters.

Also, the rental system for existing socialhousing stock has its limitations. First, thepoint system for applicants (based onHousing Law No. 144/1996) differs signifi-cantly between the sectors. Only Sectors 5and 6 favour large families living in poor con-ditions. All other sectors and the city hallclearly favour young university graduatesand households with stable incomes. Whendiscussing this issue with an activistworking at a local NGO, we realised thather situation (i.e. renting a house, having astable income, and graduated) gave hermore queuing points in Sector 1 or at thecity hall than those of a large householdwith irregular or no income and living inpoor conditions. However, in Sectors 5 and6 there is a much smaller social housingstock and greater demand due to the largernumber of poor Bucharesters and the much

722 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

-

smaller budgets of these sectors8 (Ghiţă et al.2016; Zamfirescu 2015). Sectors 2, 3, and 4 didnot publish their point system, but onlystated that they followed the above men-tioned law.

So, social housing is almost nonexistent,new plans to build additional social housingare lacking, and queuing rules differ fromsector to sector. This problematic situationwas emphasized by the planner quotedabove:

‘So I do understand the frustration [amongpoor Bucharesters], but the problem comesfrom above, from the government thatobstructs the proposals for EU funding,which surely could revitalise southernBucharest . . . On the other hand, we haveimproved many areas . . . But a communistmentality persists among many people,people waiting for someone to come and helpthem. Yet, times have changed and we are notaddressing every aspect of life for them. They[i.e. presumably poor households] also bearresponsibility for their situation.’ (Official A,July 2015)

This critical narrative connects well with whatJessop (1999, 2005) has called the critique ofself-expanding welfare provision. Thisimplies that extensive welfare regimes areblamed for generating the problems theyseek to address. As a result, these regimes arenot ‘responses to pre-given economic andsocial problems’ but constituents ‘of theirobjects of governance’ (Jessop 1999, 352).The ‘communist mentality’ was in that sensearguably generated by a previous system thataddressed socioeconomic problems throughself-expansion in the fields of, for example,housing and labour markets. That self-expan-sion, in its turn, nurtured a passive and indif-ferent ‘mentality’, because ‘everything wasprovided for’. However, that expansionstopped suddenly in 1989, and conditions inmuch of the sector’s public housing deterio-rated rapidly. In the early 1990s, small andinadequate apartments were abandoned andno longer maintained by Sector 5. In theyears to follow, instead of active maintenance

and allocation policies, the sector adopted apolicy of ‘finders keepers’ (interview withBerescu, July 2015; interview with Necsu-lescu, September 2015). All persons residingin an unclaimed apartment could registertheir apartment with Sector 5 as a socialhousing dwelling. The thousands of otherimpoverished Bucharesters who could notfind a vacant spot or afford private rentalswere condemned to the informal housingmarkets that emerged in southern Ferentari(Teodorescu 2018). These were, not unusually,apartments expropriated by local moneylenders (cămătari) or drug barons. When Iasked the planner whether economic down-turns rather than a supposed communist men-tality could explain much of the impoverishedsituation, he instead added ‘auto-segregation’of the ‘Roma residents’ to the story:

‘One can observe that many of them, even theones with income, prefer not to invest inhouses. They keep the money for otherthings, for okay and less okay investments . . .It’s a strong community now . . . and theyneed to make an effort first to accept makinginvestments themselves and to accept ourpresence. There is reticence [to do so].’

Plans and proposals for increased housinginclusion

As stated earlier, EU accession meant thatincreased public funds were available forlocal administrations in Romania. In thecase of Bucharest, these financial possibilitiesfinally offered a chance to set in motion plansfor social inclusion. What are Bucharest’sconcrete policy aims for targeting housingdecay and concentrated spatial poverty? Toanswer this question, I analyse the city’smaster plan on urban cohesion, StrategicConcept Bucharest 2035 (CSB) (PMB 2011),in relation to the existing plan, PUG(approved 2002). CSB is intended to updatePUG and guide ongoing developments in amore satisfactory way. On numerousoccasions, the two interviewed city hall plan-ners expressed high hopes for CSB.

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 723

-

Additionally, at the sector level, I highlightRUF together with some other local propo-sals intended to increase the number ofaffordable housing units.

CSB identifies serious postsocialist devel-opment setbacks that resulted in the presentsocio-economically segregated city. Itcharacterises these recent developments asthe outcome of unplanned, unequal, anduncontrolled spatial production (cf. Ion2014; Marin and Chelcea 2018). It furtherstates that the present situation can largelybe attributed to

‘decreasing quality of local governance, weakinvolvement of the central administration incoordinating the issues of an area of nationalimportance, inefficiency of local policies, andinsufficient planning capacities.’ (PMB 2011,39, author’s translation)

CSB also highlights the existence of chaoticand speculative development in thrivingparts of the city, seeing it as one of the post-socialist root causes of the production ofunaffordable housing, although the earlierquoted planner (Official A) would probablydisagree. When it comes to policy proposalsand potential revisions of existing govern-ment structures and planning forms, nothingrigorous is proposed to address the ‘weaklyinvolved’ policymakers. CSB instead advisescity hall on how to direct public investmentsto boost the competitiveness of Bucharest’seconomy, i.e. how to adopt growth strategiesand best practices from thriving urbanregions elsewhere (e.g. focusing on biotech-nology, IT, educational, and entrepreneurialhubs). Here, CSB clearly favours the flowof public money into projects that suppo-sedly generate economic growth.

CSB’s ‘sub-strategy’ on housing states thathousing is primarily the responsibility of thehomeowner. Only cases of severely deprivedtenants and homeowners should be sup-ported by ‘co-financed programmes and pro-jects, initiated by the city hall or sectors’(PMB 2011, 141). Essentially, this open-ended formulation legitimates the current

state of affairs that has tolerated segregationand housing decay. Concurrently, CSB’smore explicit calls for infrastructural projectsand urban redevelopment might contribute toan even more competitive city. Or as Purcell(2006, 1934) would have it, the promotion ofeconomic growth allows money to flow intoalready thriving areas rather than bolsteringthe wellbeing of all Bucharest’s inhabitants:it is the ‘neo-liberal instinct to sacrifice suchquestions on the altar of competitiveness’.

In fact, PUG (from 2002) refers moreexplicitly to much-needed radical change inrelation to social housing provision:

‘Though required by a large part ofBucharest’s population, nothing serious canbe achieved within the domain of publichousing without the elaboration of clearprogrammes and the existence of a new law.[New social housing programmes] shouldalso not have any political connotation; theyshould be indifferent to whoever is in power.’(p. 10 of Article 1:10, author’s translation)

Later in PUG (Article 2, on housing), it ismentioned that social housing dwellingsshould never exceed 20–30% of new private-led or PPP9 housing developments and notbe inferior in quality to other dwellings. Thisis proposed to avoid socioeconomic segre-gation and blatant discrepancies in housingquality. However, while social housing dwell-ings are capped at 30% of new housing devel-opments, reality shows that 0% is the moreaccurate output figure (INS 2016).

To further illustrate how local decision-making can disregard the needs of Buchar-est’s poorest groups, I now discuss thelowest administrative level, the sector level,and specifically Sector 5. Although it was dif-ficult to identify a coherent housing inclusionstrategy, at least two plans were given to meand discussed. One of the recent ‘concrete’policy outcomes was a 2014 document speci-fying that the sector’s then mayor, MarianVanghelie, ‘signed a partnership agreementwith the Chinese investment company Shan-dong Ningjian Construction Group, in order

724 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

-

to form a public–private partnership (PPP)that would realise the construction of aneighbourhood of 25,000 dwellings’ (2014,1, author’s translation). However, in 2017several Romanian newspapers reported thatthe Chinese company had ceased its activitiesin Romania. Nevertheless, the trust in thisplan exposes the limited role of the sectorlevel in housing provision. When discussingthe inclusion of affordable housing in theproject, Official C assured me that an unspe-cified ‘percentage’ would consist of ‘socialhousing units’:

‘These houses will be made available for aperiod of 2, 3, or 5 years, until the peoplesolve their problems and can move on to theregular housing market . . . [It is vital to have]those new apartments, because we now haveover 10,000 people in the queue waiting forsocial housing and only 4010 administereddwellings in our stock.’

The strong desire to eliminate concentrationsof poverty was incorporated in the latestmaster plan for Ferentari, RUF (Sector 52017). This document identified seven ‘mar-ginalised urban zones’ (ZUMs) in Ferentari(see Figure 1). According to RUF, theseareas are characterised by (1) low humancapital, (2) low legal employment rates, (3)precarious living conditions, and (4) ‘pro-blems with the Roma population’. Theseven ZUMs encompass 5700 dwellings and36,544 inhabitants. The percentage of Roma-nian Roma differs between ZUMs, but is esti-mated in the document to be as high as 90%in the ‘vagabond block’ areas.

Briefly stated, the plans for the ZUMs areto regenerate and revitalise the areas. Theregeneration implies, among other matters,stimulation of the local labour market,better healthcare, special attention to sub-standard housing, and increased green space.The revitalisation will focus instead onbetter urban services, such as new publicand economic centres (e.g. squares withnewly built market halls and cultural centresthat ‘promote multicultural local traditions’).What is more important (and threatening) for

the residents of the ZUMs, however, are theRUF’s aims to reclaim former public spacesand to demolish all ‘ghettoised’ blocks ofapartments and unauthorised constructionby the end of 2022 (Sector 5 2017, 94 and98). In turn, the construction of new condo-miniums is to be ‘promoted’ in the sameperiod at a cost of over EUR 70 million. Itis difficult to believe that this sum is enoughto replace thousands of decayed dwellings,and the RUF schedule was already behindschedule as of 2017. During my most recentcontact with Mr Manole (March 2018), Iwas informed that RUF is still in its initialphase: ‘Nothing has been concretised thusfar’. By the end of 2018, for example, anentire new section of Bucharest’s formerpublic transport depot was to be finished;this did not happen. Nonetheless, what didhappen were the planned evictions fromslums, for example, on Iacob Andrei Street.Following Lancione (2017), these evictionsdemonstrate the local political choice tofurther shape precarity in Ferentari.

During my interviews with the sector’sofficials, a clear narrative emerged in relationto decayed housing. Most officials expresseda desire to regenerate Ferentari by making itlook ‘just like the rest’ of the city. Thismeans, for example, that a science park anda creative industry hub need to appear inthe areas around the ZUMs (Sector 5 2017,48), so that the ‘local potential is capitalised’(Sector 5 2017, 21). Whether the deprivedhouseholds and unregistered residents willbe re-housed in these major projects is argu-ably a subordinate consideration. To illus-trate this point, I turn to the Frenchpartner’s impressions of RUF, which, follow-ing Purcell (2006), clarify the incapacity oflocal-scale to ensure increased popular par-ticipation and inclusive policies. Accordingto Mr Richard, in the years before RUF’sadoption, strong doubts existed about thesincerity of the involved actors and the feasi-bility of the set aims. Throughout RUF’spreparation stage, ‘storytelling strategies’were used to camouflage the ‘local lack ofinterest in committing themselves’ to the

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 725

-

promised and much-needed political agenda.Storytelling, he argued, was not helping the‘40,000 people living in poverty’. In hiseyes, this unwillingness was expressedthrough the obstruction of integrated multi-scalar collaboration with the national or EUlevels. Furthermore, there was no broadinterest in creating projects with inhabitantsor in creating databases of the actualnumber of people in need of new housing(including unregistered residents).

Mr Richard was in Romania in the 2011–2015 period to help local officials formulatefunding proposals and RUF. In his eyes,success in Ferentari was vital for the rest ofthe country and for Romania’s decentralisa-tion process. He noted that if a local coalitionsucceeded in redeveloping such an impover-ished urban setting, then ‘practically everyother municipality in Romania should beable to follow the “successful Ferentarimodel”’. Real solutions, such as the recon-struction of much of Ferentari’s housingstock and the immediate start of temporaryhousing construction, are, in his words, ‘toocomplex projects for the sector’ and requirea multi-scalar approach and much biggerbudgets. Sector 5 showed no intention tocooperate: ‘It never registered the amount ofsquatters and other unregistered residents,[and it] does not commit itself to longperiods of preparations for gigantic housingprojects’ (interview, September 2015).

Finally, this article considers the influence ofracism at the local institutional level and therole this has played in the unwillingness tocombat poverty among Romanian Roma—orat least in areas where the inhabitants areregarded as belonging to this minority.

Racist prejudices among local officials

In the general narrative of the local officials,Ferentari was imagined to be a ‘Gypsy area’of Bucharest. In line with Rughiniş (2010), itwas evident that Roma ethnicity was assignedto Ferentari’s residents and the spaces theyinhabited by the officials. However, as well

as this ‘hetero-attribution of Roma ethnicityto poor Bucharesters’, the narrative alsorevealed a strong racialisation of the Gypsy.‘Lazy’, ‘stubborn’, ‘uneducated’, ‘auto-segre-gating’, and ‘unreliable’ are just a selection ofthe characteristics attributed to this imaginarygroup of ‘urban Roma’ by the interviewedofficials. Racialisation should not be underes-timated in Romania’s decentralised policy-and decision-making process.

Vermeersch (2011, 2012, 2017), van Baar(2011, 2018), and Kóczé (2018) have theorisedabout Romaphobia and public governance inthe EU. Their studies have established thelimits and risks of the Europeanisationprocess in relation to local efforts to facilitateRoma inclusion. For instance, Vermeerschspecified (2017) that in the Europeanisationprocess, a substantial legal and political fra-mework for ‘European citizenship’ ismissing. Although the EU has identifiedseveral policy fields as relevant to Romainclusion (i.e. housing, health care, education,and employment), it also continues to allowfull national autonomy in identifying andaddressing the issues on the ground. Withinthis loose structure, numerous Eastern Euro-pean local administrations frame their Romacommunities as European and the majoritygroups as local. Given a neoliberal logicabout the role of local government, racialisa-tion of the Roma entitles politicians to arguethat no or limited responsibility ought to betaken for the ‘transnational Roma minority’.

As discussed in the previous subsection, inFerentari, local housing issues are to bereported by local authorities to the Bucharestdevelopment region. On top of the majorstructural funds, additional regional EU devel-opment funds can be tapped directly by localauthorities—but only to complement largerapplications with ‘soft measures’ such as voca-tional training. It is not unthinkable that, inFerentari, local administrative willingness toundertake laborious poverty reduction pro-jects is significantly diminished by Romapho-bia and alienation from Sector 5’s ‘Gypsies’.

This assertion brings us back to the same‘blunt’ official whose words I quoted earlier

726 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

-

in this article, because he illustrates veryclearly how the socioeconomic and housing-related problematics of the ‘Gypsies in Feren-tari’ are overwhelmingly regarded as a Euro-pean affair:

‘Just as the Americans did with the Mexicans,we need to invent unqualified work for Roma[across Europe]. Invite them and ask whatthey would most like to produce. Mysuggestion would be to let them produce fruitbaskets, as they did under Ceauşescu . . . Thekids, on the other hand, need good education.Let them learn French or German and read allthe poems you have over there . . . and in threeto four generations you’ll have well-educatedRoma.’ (Interview, March 2014)

Although his proposal is obviously racist andcolonialist, it is telling in two other ways. Onone hand, it transfers responsibility for policy-making from the local level (Sector 5) to theEU. Second, it relates in a striking way toone of RUF’s employment proposals: the ‘cre-ation of a Roma handcraft centre’ (meşteşugtradiţional). In this future centre, traditionalRoma crafts can be deployed: ‘The KaldareshRoma can work as smiths; the Fierari canproduce tools, etcetera’ (Sector 5 2017, 97,author’s translation). This project will verylikely not contribute to lift the thousands ofpoor Roma inhabitants out of poverty, nor isit rooted in local desires. While the projectcan be criticised for its limited impact, it canalso be contrasted to the long-standing needsexpressed by Ferentari’s residents.

In that sense, the plan to build a ‘Romahandicraft centre’ reveals both the racialisedinterpretation of Roma economic activitiesand the much broader and long-standinglack of interest in engaging with the localsituation. Even if national or Europeanfunds are obtained, better multi-scalar collab-oration and increased local involvement indecision-making are no guarantee of inclusivepolicies, though they can enable more andmuch awaited public funds to flow intoareas of Bucharest where the needs are great-est. However, the considerable humanresources needed to direct funds towards

poverty reduction and to actively engagewith local impoverished communities are,arguably, not stimulated by a context inwhich racism and distrust of ‘Gypsies’ is soopenly expressed. Hence, also racism canaggravate the ultimate outcome of local poli-tics when decentralisation is carried outincautiously. It can single out minoritiesand, thus, threaten urban democracy.

Conclusion

In the postsocialist period, decentralisationstarted under EU pressure. Initially, this wasimplemented in a chaotic and unplannedway (Profiroiu, Profiroiu, and Szabo 2017),and as a result, local authorities were able tocarry out only a limited number of tasks inthe 1990s. Following Romania’s EU acces-sion, public expenditures rose again, empow-ering deprived local authorities. However,due to poor financial management, lack ofexpertise, and patronage networks, revitalisa-tion programmes for poor districts and socialinvestments were largely neglected (Ion 2014).

Though the case of Ferentari is well alignedwith the above description, I also sought toreflect on the case using Mark Purcell’slocal trap concept. In various ways, local-scale governance has proven problematic inBucharest. To start, the existing socialhousing provision differs between sectors inBucharest. There is also no consideration ofthe much higher number of social housingapplicants in Sector 5 (Ghiţă et al. 2016). Fur-thermore, it is telling that the discussed policydocuments from both city hall and Sector 5lack clear and realistic statements about howthe needs of Ferentari’s poor householdswill be met and how housing affordabilitywill increase. One can certainly argue thatthis is due to a lack of funding, but that argu-ment is only partially true. The reality is thatRomania’s absorption of EU funds is low,and on top of that, large portions of thebudgets are earmarked for large infrastruc-tural budgets that disregard social cohesion.As such, the promotion of the economy

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 727

-

clearly outweighs the long-standing needs ofBucharest’s poorest groups. Moreover,serious engagement with Ferentari’s residentshas never been attempted. One plan, RUF,was made to address the impoverished‘40,000’, but this group was never directlyinvolved in discussions of how to spendfuture budgets for the neighbourhood. Thereason for this is difficult to determine, buthere I remind the reader that this samegroup was heavily racialised and distrustedby the interviewed officials. One could alsoconclude, at least hypothetically, that theracialisation of Romanian Roma makes therealisation of neoliberal principles easier forlocal administrations, which use racial preju-dice to justify the passivity of the local statetowards an extremely pauperised population.

In conclusion, what this case shows is that,although all actual housing procedures andfuture projects will be planned andimplemented at the local level, this does notmean that this is the right scale. It can bestated that the actual local institutions are illprepared for such a gigantic task, as MrRichard suggests, and that therefore funds arenot used for pressing social needs. It can alsobe argued that the process is not ‘localised’enough, and I have noted that the voices ofthe ‘local Gypsies’ are deliberately excludedfrom local policymaking. These findings offerthereby important evidence of the problemwith assuming that decentralisation will (auto-matically) lead to more positive outcomes.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my respondents, especially to RichardJérôme, Petre Florin Manole, Liviu Chelcea, andCătălin Berescu for giving their time and considerationto this study. Without them it would have been muchharder to research a very opaque side of Bucharest’slocal governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by theauthor(s).

Funding

This research was part of my doctoral thesis and the cor-responding fieldworks were largely financed by SSAG(Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography)and Smålands Nation’s Anna Maria Lundins TravelGrants.

Notes

1 Bucharest has a two-level governance structure witha city hall and six administrative units, called sectors(sectoare).

2 Roma comprised 1.27% of Bucharest’s totalpopulation and 2.57% of Sector 5’s population in2011, though these figures are greatlyunderestimated. Sector 5’s master plan for Ferentari(Regenerare Urbană Ferentari, RUF; see Sector 52017, 67–68) presents ethnic statistics for six of theseven most deprived areas of Ferentari. In theseareas, 85.6% of the residents (or 19,628) areidentified as Roma.

3 The two officials from city hall were part of a groupof nine that together form the Urban PlanningCommission. Sector 5 has no such commission. In arecent report (https://www.oar-bucuresti.ro/documente/sedinte_ctatu/2017-03-29/CTATU-2017-03-29.pdf) from the Urban PlanningCommission, complaints are raised about receivingdevelopment requests from Sector 5 due toincompetence: ‘People continue being sent to the‘Big’ city hall, as no specialised commission exists inSector 5’. The five people I spoke with from Sector 5include a large part of the staff involved in urbanplanning (Direcţia Arhitect Şef) and housing policy(Direcţia Generală Operaţiuni).

4 All officials are identified by letters: officials A and Bare city hall planners; officials C to G are employedin Sector 5, C in public works, D in socialassistance, E and F in public works, and G in urbanplanning.

5 In 2019, 27% of the city hall’s budget wasearmarked for large investment projects andinfrastructure, while only 9% would go to socialassistance. See Proiectul de Buget al MunicipiuluiBucuresti pe anul 2019.

6 Romania has eight development regions. Of these,seven are ‘less developed’ while one, Bucharest-Ilfov, is classified as ‘more developed’. Thegoverning council of a region is not directlyelected; instead, it is appointed by the presidentsand representatives of the counties andmunicipalities, respectively, that are part of thedevelopment region. The development regionscorrespond to the NUTS-2 level of the Europeanstatistics system (Profiroiu, Profiroiu, and Szabo2017).

728 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

https://www.oar-bucuresti.ro/documente/sedinte_ctatu/2017-03-29/CTATU-2017-03-29.pdfhttps://www.oar-bucuresti.ro/documente/sedinte_ctatu/2017-03-29/CTATU-2017-03-29.pdfhttps://www.oar-bucuresti.ro/documente/sedinte_ctatu/2017-03-29/CTATU-2017-03-29.pdf

-

7 The ANL was ‘charged with the task of providinghousing to certain disadvantaged groups with fewerchances on the housing market and that had notbenefited from the earlier large-scale privatisation.The planned dwellings were to be sold withconvenient mortgages, while the rentals were alsoto be subject to right-to-buy schemes in the future . . .With only 31,000 new public housing units built,400 of which were for poor Roma households, ANLfailed to increase housing affordability.’(Teodorescu 2019, 29)

8 All sectors have autonomous budgets: Sector 1 hasthe largest one, while Sector 5 has the smallest.

9 PPP stands for public–private partnership.10 This official refers to two centrally-located blocks of

apartments used for emergency housing. The totalnumber of social housing in Sector 5 is unknown tohim or his colleagues and not made public either.Also the public housing administration (AFI) doesnot provide these figures.

ORCID

Dominic Teodorescu http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8287-2213

References

Amann, Wolfgand, Ioan Bejan, and Alexis Mundt. 2013.“The National Housing Agency–A Key Stakeholder inHousing Policy.” In Social Housing in TransitionCountries, edited by József Hegedüs, Nora Teller, andMartin Lux, 210–223. Abingdon: Routledge.

Arpagian, Jasmine, and Stuart C. Aitken. 2018. “WithoutSpace: The Politics of Precarity and Dispossession inPostsocialist Bucharest.” Annals of the AmericanAssociation of Geographers 108 (2): 445–453.doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1368986.

Attoh, Kafui A. 2011. “What Kind of Right is the Right tothe City?” Progress in Human Geography 35 (5):669–685. doi:10.1177/0309132510394706.

Berescu, Cătălin, Mina Petrović, and Nora Teller. 2013.“Housing Exclusion of the Roma. Living on the Edge.”In Social Housing in Transition Countries, edited byJózsef Hegedüs, Nora Teller, and Martin Lux, 98–116. Abingdon: Routledge.

Calciu, Daniela. 2016. “Memories and the City, Heritageand Urbanity.” In Space and Time Visualisation, edi-ted by Maria Boştenaru-Dan, and Cerasella Crăciun,113–124. Cham: Springer.

Chelcea, Liviu, and Ioana Iancu. 2015. “An Anthropologyof Parking: Infrastructures of Automobility, Work, andCirculation.” Anthropology of Work Review 36 (2):62–73. doi:10.1111/awr.12068.

Chelcea, Liviu, Raluca Popescu, and Darie Cristea. 2015.“Who are the Gentrifiers and How Do They ChangeCentral City Neighbourhoods? Privatization, Com-modification, and Gentrification in Bucharest.” Geo-grafie 120 (2): 113–133.

Chelcea, Liviu, and Gergó́ Pulay. 2015. “NetworkedInfrastructures and the ‘Local’: Flows and Connectivityin a Postsocialist City.” City 19 (2-3): 344–355.doi:10.1080/13604813.2015.1019231.

Clapp, Alexander. 2017. “Romania Redivivus.” New LeftReview 108: 5–41.

Creţan, Remus, and Ryan Powell. 2018. “The Power ofGroup Stigmatization: Wealthy Roma, Urban Spaceand Strategies of Defence in Post-socialist Romania.”International Journal of Urban and Regional Research42 (3): 423–441. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12626.

Csepeli, György, and Dávid Simon. 2004. “Constructionof Roma Identity in Eastern and Central Europe: Per-ception and Self-identification.” Journal of Ethnic andMigration Studies 30 (1): 129–150. doi:10.1080/1369183032000170204.

Dobre, Ana M. 2010. “Romania: From Historical Regionsto Local Decentralization via the Unitary State.” In TheOxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracyin Europe. https://search.crossref.org/?q=10.1093%2Foxfordhb%2F9780199562978.003.0030#.

Geddes, Mike. 2005. “Neoliberalism and Local Govern-ance–Cross-National Perspectives and Specu-lations.” Policy Studies 26 (3-4): 359–377. doi:10.1080/01442870500198429.

Ghiţă, Alexandru F., Ciprian Ciucu, Alexandru Damian,Alexandra Toderiţă, Roxana Albişteanu, andPopescu. Ruxandra. 2016. Policy Paper Nr. 1 /Ianuarie 2016: Locuirea socială ı̂n Bucureşti. Întrelege şi realitate. Accessed December 10, 2018 www.cdut.ro.

Goodwin, Mark, and Joe Painter. 1996. “Local Govern-ance, the Crises of Fordism and the Changing Geo-graphies of Regulation.” Transactions of the Instituteof British Geographers 21 (4): 635–648. doi:10.2307/622391.

INS (National Institute of Statistics). 2016. Dimensiuni aleincluziunii sociale ı̂n România. Bucharest: InstitutulNaţional de Statistică. Accessed August 10, 2017.http://www.insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/dimensiuni_ale_incluziunii_sociale_in_romania_1.pdf.

Ion, Elena. 2014. “Public Funding and Urban Governancein Contemporary Romania: The Resurgence of State-led Urban Development in an Era of Crisis.” Cam-bridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7(1): 171–187. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst036.

Jessop, Bob. 1999. “The Changing Governance of Wel-fare: Recent Trends in its Primary Functions, Scale,and Modes of Coordination.” Social Policy andAdministration 33 (4): 348–359. doi:10.1111/1467-9515.00157.

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 729

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8287-2213http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8287-2213https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1368986https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510394706https://doi.org/10.1111/awr.12068https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1019231https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12626https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183032000170204https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183032000170204https://search.crossref.org/?q=10.1093%2Foxfordhb%2F9780199562978.003.0030#https://search.crossref.org/?q=10.1093%2Foxfordhb%2F9780199562978.003.0030#https://search.crossref.org/?q=10.1093%2Foxfordhb%2F9780199562978.003.0030#https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870500198429https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870500198429http://www.cdut.rohttp://www.cdut.rohttps://doi.org/10.2307/622391https://doi.org/10.2307/622391http://www.insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/dimensiuni_ale_incluziunii_sociale_in_romania_1.pdfhttp://www.insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/dimensiuni_ale_incluziunii_sociale_in_romania_1.pdfhttp://www.insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/dimensiuni_ale_incluziunii_sociale_in_romania_1.pdfhttps://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rst036https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00157https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00157

-

Jessop, Bob. 2005. “The Political Economy of Scale andEuropean Governance.” Tijdschrift voor economischeen sociale geografie 96 (2): 225–230. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00453.x.

Jessop, Bob, Neill Brenner, and Martin Jones. 2008.“Theorizing Sociospatial Relations.” Environment andPlanning D: Society and Space 26 (3): 389–401.doi:10.1068/d9107.

Kóczé, Angéla. 2018. “Race, Migration and Neoliberal-ism: Distorted Notions of Romani Migration in Euro-pean Public Discourses.” Social Identities 24 (4):459–473. doi:10.1080/13504630.2017.1335827.

Lancione, Michele. 2017. “Revitalising the Uncanny:Challenging Inertia in the Struggle Against ForcedEvictions.” Environment and Planning D: Society andSpace 35 (6): 1012–1032. doi:10.1177/0263775817701731.

Lancione, Michele. 2019. “The Politics of Embodied UrbanPrecarity: Roma People and the Fight for Housing inBucharest, Romania.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical,Human, and Regional Geosciences 101: 182–191.doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.008.

Light, Daniel, and Craig Young. 2015. “Public Space andthe Material Legacies of Communism in Bucharest.” InPost-Communist Romania at 25, edited by LaviniaStan, and Diane Vancea, 41–62. Lanham: Lexington.

Marcińczak, Szymon, Michael Gentile, Samuel Rufat, andLiviu Chelcea. 2014. “Urban Geographies of HesitantTransition: Tracing Socioeconomic Segregation inPost-Ceauşescu Bucharest.” International Journal ofUrban and Regional Research 38 (4): 1399–1417.doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12073.

Marin, Vera, and Liviu Chelcea. 2018. “The Many (Still)Functional Housing Estates of Bucharest, Romania: AViable Housing Provider in Europe’s Densest CapitalCity.” In Housing Estates in Europe, edited by DanielBaldwin Hess, Tiit Tammaru, and Maarten van Ham,167–190. Cham: Springer.

Nae, Mariana, and David Turnock. 2011. “The NewBucharest: Two Decades of Restructuring.” Cities 28(2): 206–219. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.04.004.

O’Neill, Bruce. 2010. “Down and Then Out in Bucharest:Urban Poverty, Governance, and the Politics of Placein the Postsocialist City.” Environment and Planning D:Society and Space 28 (2): 254–269. doi:10.1068/d15408.

O’Neill, Bruce. 2014. “Cast Aside: Boredom, DownwardMobility, and Homelessness in Post-CommunistBucharest.” Cultural Anthropology 29 (1): 8–31.doi:10.14506/ca29.1.03.

O’Neill, Bruce. 2017. “The Ethnographic Negative: Cap-turing the Impress of Boredom and Inactivity.” Focaal78: 23–37. doi:10.3167/fcl.2017.780103.

PMB (Primăria Municipiului Bucureşti). 2011. ConceptulStrategic Bucureşti. Bucharest: PMB.

Powell, Ryan, and John Lever. 2017. “Europe’s Perennial‘Outsiders’: A Processual Approach to Roma

Stigmatization and Ghettoization.” Current Sociology65 (5): 680–699. doi:10.1177/0011392115594213.

Profiroiu, Constantin M., Alina G. Profiroiu, and SeptimuR. Szabo. 2017. “The Decentralization Process inRomania.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Decentrali-sation in Europe, edited by José Ruano, and MariusProfiroiu, 353–387. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pulay, Gergó́. 2015. “The Street Economy in a PoorNeighbourhood of Bucharest.” Gypsy Economy:Romani Livelihoods and Notions of Worth in the 21stCentury 3: 127–144.

Purcell, Mark. 2002. “Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to theCity and its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant.” Geo-Journal 58 (2-3): 99–108. doi:10.1023/B:GEJO.0000010829.62237.8f.

Purcell, Mark. 2006. “Urban Democracy and the LocalTrap.” Urban Studies 43 (11): 1921–1941. doi:10.1080/00420980600897826.

Purcell, Mark. 2013. “The Right to the City: the Struggle forDemocracy in the Urban Public Realm.” Policy andPolitics 41 (3): 311–327. doi:10.1332/030557312X655639.

Rughiniş, Cosima. 2010. “The Forest Behind the BarCharts: Bridging Quantitative and QualitativeResearch on Roma/Ţigani in Contemporary Roma-nia.” Patterns of Prejudice 44 (4): 337–367. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2010.510716.

Sector 5. 2017. Regenerare Urbană Ferentari. Bucharest:Sector 5. Accessed August 10, 2017. http://www.sector5.ro/media/2763/ruf-cld.pdf.

Şoaită, Adriana M. 2017. “The Changing Nature ofOutright Home Ownership in Romania: HousingWealth and Housing Inequality.” In Housing Wealthand Welfare, edited by Caroline Dewilde, andRichard Ronald, 236–257. Cheltenham: EdwardElgar.

StudioBASAR. 2010. Evicting the Ghost: Architecture ofSurvival. Bucharest: Centrul de Introspecţie Vizuală.

Surubaru, Neculai-Cristian. 2017. “AdministrativeCapacity or Quality of Political Governance? EUCohesion Policy in the New Europe, 2007–13.”Regional Studies 51 (6): 844–856. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1246798.

Teodorescu, Dominic. 2018. “The Modern Mahala: Mak-ing and Living in Romania’s Postsocialist Slum.” Eur-asian Geography and Economics 59 (3-4): 436–461. doi:10.1080/15387216.2019.1574433.

Teodorescu, Dominic. 2019. “Dwelling on SubstandardHousing: A Multi-site Contextualisation of HousingDeprivation among Romanian Roma.” PhD diss.,Uppsala University.

Tosics, Ivan. 2016. “Integrated Territorial Investment: aMissed Opportunity?” In EU Cohesion Policy, editedby John Bachtler, Peter Berkowitz, Sally Hardy, andTatjana Muravska, 284–296. Abingdon: Routledge.

van Baar, Huub. 2011. “Europe’s Romaphobia: Proble-matization, Securitization, Nomadization.”

730 CITY VOL. 23, NO. 6

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00453.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00453.xhttps://doi.org/10.1068/d9107https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2017.1335827https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2017.1335827https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817701731https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817701731https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.008https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12073https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2010.04.004https://doi.org/10.1068/d15408https://doi.org/10.1068/d15408https://doi.org/10.14506/ca29.1.03https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2017.780103https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392115594213https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392115594213https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000010829.62237.8fhttps://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000010829.62237.8fhttps://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600897826https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600897826https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655639https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655639https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2010.510716https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2010.510716http://www.sector5.ro/media/2763/ruf-cld.pdfhttp://www.sector5.ro/media/2763/ruf-cld.pdfhttps://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1246798https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1246798https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2019.1574433

-

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29(2): 203–212. doi:10.1068/d2902ed1.

van Baar, Huub. 2018. “Contained Mobility and theRacialization of Poverty in Europe: The Roma at theDevelopment–Security Nexus.” Social Identities 24(4): 442–458. doi:10.1080/13504630.2017.1335826.

Vermeersch, Peter. 2011. “Europeanisering en de Roma:op zoek naar maatschappelijke inclusie in een nieuwepolitieke en institutionele contekst.” Tijdschrift voorSociologie 3 (4): 414–436.

Vermeersch, Peter. 2012. “Reframing the Roma: EUInitiatives and the Politics of Reinterpretation.” Journalof Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (8): 1195–1212.doi:10.1080/1369183X.2012.689175.

Vermeersch, Peter. 2017. “How Does the EU Matter for theRoma? Transnational Roma Activism and EU SocialPolicy Formation.” Problems of Post-Communism 64(5): 219–227. doi:10.1080/10758216.2016.1268925.

Vincze, Eniko. 2018. “Ghettoization: The Production ofMarginal Spaces of Housing and the Reproduction ofRacialized Labour.” In Racialized Labour in Romania:

Spaces of Marginality at the Periphery of GlobalCapitalism, edited by Eniko Vincze, Norbert Petrovici,Cristina Raţ, and Giovanni Picker, 63–96. Cham:Palgrave Macmillan.

Vincze, Eniko, and Cristina Rat. 2013. “Spatialization andRacialization of Social Exclusion. the Social and CulturalFormation of ‘Gypsy Ghettos’ in Romania in a EuropeanContext.” Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai 58 (2):5–21.

Vincze, Eniko, and George I. Zamfir. 2019. “RacializedHousing Unevenness in Cluj-Napoca Under CapitalistRedevelopment.” City 23 (4–5): 439–460. doi:10.1080/13604813.2019.1684078.

Zamfirescu, Irina M. 2015. “Housing Eviction, Displace-ment and the Missing Social Housing of Bucharest.”Calitatea vieţii 26 (2): 140–154.

Dominic Teodorescu recently obtained hisPhD at the Uppsala University and is now afixed-term lecturer at Uppsala University’sSocial and Economic Geography Department.Email: [email protected]

TEODORESCU: RACIALISED POSTSOCIALIST GOVERNANCE IN ROMANIA’S URBAN MARGINS 731

https://doi.org/10.1068/d2902ed1https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2017.1335826https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2017.1335826https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.689175https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1268925https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1268925https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2019.1684078https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2019.1684078mailto:[email protected]

AbstractIntroductionLocal governance, postsocialist citizenship and marginalising the poorBucharest’s local trap: from top-down planning to badly managed governanceGoverning Bucharest’s poor citizens: some examples of displacement practicesThe situation in Ferentari

Actual and future housing inclusion efforts: does it work and for whom should it work?Existing social housing policies in FerentariPlans and proposals for increased housing inclusionRacist prejudices among local officials

ConclusionAcknowledgementsDisclosure statementNotesORCIDReferences