Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

-

Upload

ardel-b-caneday -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

1/34

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

2/34

132 TRINITY JOURNAL

companies call them). In years to come many a Christian attemptedto provide me with "good" reasons why God would have ordained

my brother's death. Those discussions served to spur my reflectionon divine providence for over twenty years, (p. 9)

Sanders has forged his view of God in the crucible of his deeppersonal pain. He describes a similar experience about fifteen yearsafter his brother's death, when he was struck by a pastor's wordsbeside the grave of an infant girl, "God must have had a good reasonfor taking her home" (p. 10). Sanders explains, "Of course 'takingher home' is a euphemism for God's killing her" (p. 10). Later the

parents of the child inquired of Sanders, "Why did God kill our babygirl?" (p. 10). He tells us they were angry with God, but their angerwas "directed at a particular model of God," not at God himself (p.10).

As Sanders came to terms with his brother's tragic death, hechafed under the thought that God had anything to do with tragedy.And he still does. Despite his claims that The God Who RisL onlyoccasionally critiques the traditional and orthodox view of God'sprovidence, it is evident that his youthful anger has turned toscolding and deriding the theologians who, as he sees it, created theGod to whom he first raised his voice in anger. Sanders sees twoalternative ways to view God, and he strongly dislikes one of them.

Either God does take risks or does not take risks in providentiallycreating and governing the world. Either God is in some respectsconditioned by the creatures he created or he is not conditioned bythem. If God is completely unconditioned by anything external tohimself, then God does not take any risks. According to the no-riskunderstanding, no event ever happens without God's specificallyselecting it to happen. Nothing is too insignificant for God'smeticulous and exhaustive control. Each and every death, civil war,famine, wedding, peaceful settlement or birth happens becauseGod specifically intends it to happen. Thus God never takes anyrisks and nothing ever turns out differently from the way Goddesires. The divine will is never thwarted in any respect, (p. 10)

With a touch of mockery, he scolds these "no-risk" theologians,

It is not up to human beings to dictate the sort of providence God

must exercise. Instead, we should try to discern what sort ofsovereignty God has freely chosen to practice, (p. 11)

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

3/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 133

caused the death ofmy brother was a tragedy. God does not have aspecific purpose in mind for these occurrences, (p. 262)

These are the thoughts over which John Sanders has brooded forseveral years and which he has hatched in several published works,the most recent being The GodWho Risks. However, it is not as ifSanders came to his view of God unaided. At least three otherfactors prepared the way to "make it safe" for Sanders to adopt andpublish his bold new view of God: (1) the rise of process theologyamong liberal theologians since the 1960s, which provides aparadigm of thought; (2) the popularizing of the ideas of process

theism by Harold Kushner's When Bad Things Happen to GoodPeople;

2

and (3) validation by "evangelical sympathizers" of process theism,such as Clark Pinnock and Richard Rice.3

So, strongly disliking the model of God he inherited, Sandersconceives of his mission as "iconoclastic" (his own term)to shatterthe prevailing concept of "God as king" and replace it with "themetaphor of God as risk taker" (p. 11). Sanders recognizes that manyreaders will be shocked by his notion of God as "a risk taker" (p. 11),so he promptly seeks to calm some readers. He intends this impactto be reduced proportionally to the degree that one already agreeswith his "particular theological model: a personal God who entersinto genuine give-and-take relations with his creatures" (p. 12).People who will be scandalized do not embrace "relational theism,"which is any view that "includes genuine give-and-take relationsbetween God and humans such that there is receptivity and a degreeof contingency in God" (p. 12). Therefore, he expects to scandalizeall who cling to "an impersonal deity" (deists) or to "a personaldeity who meticulously controls every event" (determinists of allkinds [p. 12]). But he anticipates agreement from "relational theists,"

who embrace "'freewill theism,' simple foreknowledge, presentism(the openness of God) and some versions of middle knowledge" (p.12). It seems that Sanders wants to relocate the line of division whichhe, Richard Rice, Clark Pinnock, William Hasker, the Basingers, andothers have drawn between "open theism" and "traditional theism."Evidently the "open theists" initially drew the circle too small whenthey first circumscribed their views by redefining omniscience tomean, "God's knowledge is coextensive with reality. God knows allthere is to know. Since, it is claimed, the future actions of free beings

are unknowable, God does not know them" (305 n. 121).4

They

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

4/34

134 TRINITYJOURNAL

began to find themselves somewhat isolated by their own restrictivedesignation "open theism/' and they found their view of God

denounced as "heresy/7

even by an Arminian theologian who wasoutside their narrowly defining arc.5Understandably, then, Sanders

wants to enlarge his theological tent in an attempt to find alliesamong those who hold to what he calls "relational theism" (p. 12).

While Sanders attempts to soften distinctions between "opentheism" and the Arminian segment of classical theism, heexaggerates theological differences within classical theism between

Arminianism and Calvinism. He carefully shapes the wholediscussion by painting the perspective of his theological opponents

flat, with no contours. Their views are portrayed in darkcolors, withbroad and coarse strokes, while he dips his fine brush in warm huesto provide detail and depth to his own viewpoint. He identifies oneelement of his opponents' understanding of what the Bible saysconcerning God, and he isolates it from other elements in theirtheological beliefs so that he presents them, not at their best, but asholding positions they in fact do not adopt. His book is saturatedwith appeals to prejudices and feelings (ad hominem) rather than todiscernment. It is charged with devices designed to maneuver hisown viewpoint into more advantageous acceptance by excludingcrucial elements of his opponents' viewpoints (diversion).Consequently he excludes any view that stands between his ownand his caricature (false disjunction). Sanders has crafted a prima facieargument to evoke dislike for a "no-risk" view, and thus, by default,to gain devotees for his own "God-at-risk" view. The usefulness ofhis book is tarnished by the fact that he has reduced even carefullynuanced compatibilism to a fatalism which is "nonrelational." At thesame time, from the opposite end of the spectrum, he has drawn alarger arc around "open theism" by renaming it "relational theism."

He thereby attempts to relocate the center of classical theism closerto his own position, which he calls "presentism."

Therefore, he projects a new model of God's providence byforcing his readers to view God through his narrow aperture and"through the lens of divine risk taking" (p. 14). With this as hisagenda, Sanders brings together philosophical theology and biblical

be known ahead of time. They literally do not yet exist to be known" ("God LimitsHis Knowledge/' in Predestination andFree Will: Four ViewsofDivine Sovereignty aFreedom [Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1986] 157). Cf. Gregory A. Boyd and Edward

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

5/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 135

theology to sketch his view ofThe God who RisL while putting at riskthe God of orthodox theism. So,

the portrait of God developed here is one according to which Godsovereignly wills to have human persons become collaboratorswith him in achieving the divine project of mutual relations of love,(p. 12, emphasis added)

This expression, "the divine project/' is Sanders's favoritedesignation for God's providential work with his creation, for avariation of it occurs repeatedly throughout the book. Unforeseen toGod, his project aborted (pp. 49,230). That's no problem in Sanders'stheologyGod can simply switch from "plan A to plan B" (see p.64).

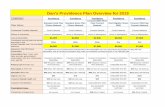

II. AN OVERVIEWOF THE BOOK

Because of considerable repetition in Sanders's book, thisoverview will be unbalanced, with larger summary given to the firstthree chapters, where he attempts to deal with biblical evidence forhis view of God and the world. It is important for readers of this

review to see Sanders's own comments upon biblical texts.

A. Chap. 2: "The Nature of the Task" (pp. 15-38)

This chapter addresses the crucial issue of metaphors andimagery in theological discussions. Sanders correctly states, "Thelanguage of Scripture is 'reality depicting' in that what weunderstand to be real is mediated through its metaphors andimages" (p. 15). However, Sanders does not tether his discussion to

biblical "metaphors and images"; his interest is not to develop acoherent portrait of God's providence by examining the full range ofbiblical "metaphors and images." Rather, when he talks about the"language of Scripture," what he has in mind is the biblicalmetaphor that is regarded as the "control metaphor" by which weshould read the Bible. He says,

When we read the Scripture through the lenses of certain models,we tend to interpret Scripture from that perspective. Thus it is notsurprising that someone affirming God as the immutable kingwould view the biblical texts on divine repentance asanthropomorphisms so that God never actually changes his mind,

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

6/34

136 TRINITYJOURNAL

doctrines and practices such as divine repentance and petitionaryprayer, (p. 16)

His discussion of the place of "anthropomorphism" in talk aboutGod is engaging. He properly points out that anthropomorphismhas both "a narrow and a broad meaning" (p. 22). The narrowconcerns specific and well-recognized figures of speech in whichhuman qualities such as arms, hands, and eyes are ascribed to God.In the broader sense, because "all our language about God is humanlanguage," it is therefore anthropomorphic. Why? Because, in concert

with theologians such as Herman Bavinck,6

Sanders rightly affirms

"we are inevitably predicating properties of God that are derivedfrom human categories" (p. 22). If we want to speak of God, we mustchoose between using anthropomorphic language or completesilence. So, he is correct to say, "If we think of God as personal,living and interacting with us, then we are speakinganthropomorphically" (p. 23).

Howdoes anthropomorphism disclose God to humans? Sanderssays,

Anthropomorphic language does not preclude literal predication to

God What I mean by the word literalis that our language aboutGod is reality depicting (truthful) such that there is a referent, another, with whom we are in relationship and of whom we havegenuine knowledge, (p. 25)

He reasons "that Jesus is the consummate anthropomorphism,"which prepares for his later literalizing of certainanthropomorphisms (p. 26).

Sanders does not accept any attempt on the part of orthodoxChristians to explain biblical anthropomorphism as God's"accommodation" to "our limited abilities to understand" (p. 33). Healso discredits any appeal to paradox in an effort to represent humanlimitations to explain the tension that seems to exist between God'ssovereignty and human accountability (p. 35). He thinks all suchappeals "fail to take seriously enough the conditions of ourcreatedness" (p. 37). Therefore, according to Sanders, both D. A.Carson and J. I. Packer are guilty of attempting to go beyond whatGod has revealed when they acknowledge an insoluble tension

between divine sovereignty and human responsibility, best

represented in compatibilist terms.

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

7/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 137

B. Chap. 3: "Old Testament Materials" (pp. 39-89)

In chaps. 3 and 4, Sanders explores "the nature of the divineproject" in the biblical narrative and concludes that "there is morethan sufficient biblical data teaching that God does not exercisemeticulous providence in such a way that the success of his projectis, in all respects and without qualification, a foregone conclusion"(pp. 39-40).

Though God created all things, this is no guarantee that thecreator will get his way with his creation (p. 43). God's projectaborts; "creation has miscarried" (p. 49). "God does not give up hopeand will continue his project through Noah's family" (p. 50). God isvulnerable to his creatures. God's test of Abraham really is a test ofGod, for "God genuinely does not know" whether or not Abrahamtrusts him (p. 52). He cites Gen 22:12"'Do not lay a hand on theboy,' he said. 'Do not do anything to him. Now I know that you fearGod, because you have not withheld from me your son, your onlyson'""He did not know. Now he knows" (p. 52, he quotesBrueggeman). Sanders explains,

Many commentators either pass over this verse [Gen 22:12] insilence or dismiss it as mere anthropomorphism. It is oftensuggested that the test was for Abraham's benefit, not God's. Itshould be noted, however, that the only one in the text said to learnanything from the test is God. (p. 52)

Apparently it does not occur to Sanders that he has proved too muchfor his "open theist" view, because his reading of the text indicatesthat God does not know the present reality of Abraham's fear untilafter God tested him. This contradicts his own definition of"presentism," which he defines as God's "exhaustive knowledge ofthe past and present" (p. 199). ^

Gen 50:20, a verse that affirms that God effectively succeeds athis plans, has consoled innumerable Christians. But it now meanssomething quite different. Sanders explains,

I take this to mean that God has brought something good out oftheir evil actions. God was not determining everything in Joseph'slife, but God did remain "with" him. (p. 55)

The subject and its verb"God intendedit for good"has nothing todo with intention at all but refers to God's ability to mop up the

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

8/34

138 TRINITY JOURNAL

subjects his efforts to the hands of people who "could havefailedthey could have acted differently and let the boys die" (p.

57). "God works with what is available in the situation" (p. 57).Later, God tells Moses that Pharaoh will not let the people go "basedon his knowledge of the king's stubborn nature" (p. 59). Thishardening of Pharaoh's heart "is commonly citel in discussions ofdivine sovereignty to demonstrate that God is in full control of evenoppressive and disastrous situations" (p. 59). Sanders thinksotherwise.7 Instead, "In making use of the resources available, divinesovereignty does not exercise absolute control over the human order.God does not easily get his way with either Moses or Pharaoh" (p.

60). Sanders devotes an extended excursus to biblical texts thatpresent God as changing his mind or repenting. He objects toanyone who explains "divine repentance" as anthropomorphiclanguage of accommodation.

On what basis do these thinkers claim that these biblical texts donot portray God as he truly is but only God as he appears to us?How can they confidently select one biblcal [sic] text as an "exact"description of God and consign others to the dustbin of

anthropomorphism? (p. 68)

Sanders dislikes John Calvin's explanation of "divinerepentance" texts, but he formally finds himself agreeing withCalvin later in the same excursus when he affirms, "Metaphors donot provide us with an exact correspondence to reality, but they doprovide a way of understanding reality" (p. 72). Isn't this what JohnCalvin, Paul Helm, and Bruce Ware8 also mean when they say, asSanders paraphrases,

Ifthe Bible in one place predicates a change ofmind with respect toGod [e.g., 1 Sam 15:11] but elsewhere proclaims that God cannotchange his mind because "God is not human" [e.g., 1 Sam 15:29],then the texts predicating a change of mind in God are to be takenas anthropomorphic expressions that are not literally true of God.(p. 67)

Yet Sanders is only in formal agreement with these theologiansbecause he claims that they do not give anthropomorphism its

proper due. Sanders believes

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

9/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 139

A better approach to the divine-repentance texts is to acknowledge

that they are metaphorical in nature. Metaphors do not provide uswith an exact correspondence to reality, but they do provide uswith a way of understanding reality. No single metaphor capturesthe biblical God. Rather, a number of metaphors are used in orderto build up a portrait of God. (p. 72)

Would Calvin or Helm or Ware disagree? Sanders clarifies twoessential differences he has with them. First, Sanders elevates"divine repentance" to the level of "a significant controlling metaphorin the biblical narrative" (p. 72, italics added). Though it is true that

no single metaphor is capable of disclosing God in the Bible, Sandersdoes insist that divine repentance, because it is so "pervasive in theOld Testament" (p. 72), should be the aperture through which therevelatory light of the biblical narrative should present itself to thehuman mind. The second essential difference is that Sanders acceptsevery anthropomorphic use of repentance to portray God as he reallyis. God really does change his mind, because these "repentance"texts are not "merely anthropomorphisms" (pp. 67,69,72).9

Other pieces of this segment beg for attention, but space

prohibits. Sanders nicely sums up his conclusion to the review of OTmaterial:

God resourcefully tries out different paths in his efforts to bring hisproject toward a successful completion. God's activity does notunfold according to some heavenly blueprint whereby all goesaccording to plan. God is involved in a historical project, not aneternal plan. (p. 88)

The "divine project" is an experiment that has gone awry; it is a

divine adventure (cf. p. 260, where Sanders uses these words todescribe providence).

G Chap. 4: "New Testament Materials" (pp. 90-139)

Sanders refers to Jesus as "the ultimate anthropomorphism" (p.90). "In Jesus we see the genuine character of God, who is neither anomnipotent tyrant nor an impotent wimp" (p. 91). He clarifies,

The king of creation does not intimidate us or dominate us, as inthe traditional monarchical model of providence. Instead, the kingsends his son in order to reconcile us, making us children of the

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

10/34

140 TRINITY JOURNAL

king and siblings of Christ. God is indeed King and Father, thoughan atypical king and father, (p. 92)

Appeals to false disjunctions, such as these, characterize the book.Sanders traces select elements from the gospels to make his

point: "The way of providence in the life of Jesus did not occur bysome predetermined plan. Everything is not being worked outaccording to some eternal script" (p. 137). "Furthermore, in contrastto the no-risk model, Jesus did not go about cleaning up the messcaused by the disease, disasters and misery that his Father hadcaused" (p. 138). Truly an amazing caricature of the view he

opposes.Every page of this chapter, along with the endnotes, contains

statements that require close attention, but a few citations mustsuffice. Concerning God's appointment of Mary to conceive and bearthe Savior of the world, Sanders says, "God became genuinelydependent" upon Mary and "did not merely work through" her as ifshe were a "secondary cause" (p. 92). Commenting on Luke 1:26-33,he claims, "God does not unilaterally achieve his goal of incarnationby forcing his will on Mary" (p. 92). So,

If Mary had declined . . . then God would have sought otheravenues. After all, it is doubtful that there was only one maiden inall of Israel through whom God would work. God is resourceful infinding people and then equipping them with the elementsnecessary for accomplishing his purposes, (p. 92)

Sanders tells us it is a mistake to believe that before CreationGod planned Jesus' crucifixion. Likewise, it is a mistake to believethat God had previously appointed Judas to betray Jesus to his

death. So, when Jesus announces during the Passover meal "that oneof the disciples will 'hand him over' (paradidomi does not mean'betray') to the temple authorities" (p. 98), we are wrong to thinkthat Judas "betrayed" Jesus, and we are wrong to suppose that thisis working out in keeping with some grand design that God hadpreviously planned. When Jesus tells Judas, "What you are about todo, do quickly" (John 13:27), Sanders claims Jesus would not have"told Judas to go out and deliberately commit a sin. In this light it isclear that Judas is not betraying Jesus and that Jesus is not issuing

any prediction of such activity" (p. 99). Sanders assuredly claims, "Arisk is involved here, since there is no guarantee which way Judaswill decide None of this was predetermined" (p 99) Sanders

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

11/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 141

framework ogeneralprovidence, then in its outworking God does notalways get his way because he is contingent and dependent upon

human choices. Sanders believes this may be seen plainly in theCrucifixion. In the Garden of Gethsemane,

Jesus wrestles with God's will because he does not believe thateverything must happen according to a predetermined plan. . . .Together they determine what the will of God is for this historicalsituation. Although Scripture attests that the incarnation wasplanned from the creation of the world, this is not so with the cross.The path of the cross comes about only through God's interactionwith humans in history. Until this moment in history other routes

were, perhaps, open.... Jesus is in the canoe heading for the falls.There is yet time to get over to shore and portage around the falls.Jesus seeks to determine if that option meets with his Father'sfavor. But the canyon narrows even for God. (pp. 100-1)

Incredibly, Sanders tells us the Crucifixion was not part of God'sstory line until the night before it occurs. For on that dark night inthe Garden "Father and Son, in seeking to accomplish the project,both come to understand that there is no other way" (p. 101). But

once it is determined that Jesus must die, uncertainty still remains."Will this gambit work?" (p. 101).Sanders acknowledges, "The notion that the cross was not

planned prior to creation will seem scandalous to some readers" (p.101). Indeed it will. For most readers will know that there arenumerous places in all the gospels that make it clear that the Crosswas not planned the night before the Crucifixion, not to mentionbefore Creation. Astonishingly, there is not a hint of reflection uponthese texts (e.g., Mark 8:31ff; 9:31-32; 10:32ff).

Sanders makes an effort to quell the doubts of dubious readerswho wonder about all those OT texts which they believe prophesythe death of Jesus Christ. He cannot address all the texts, but heconsiders one"they have pierced my hands and my feet" (Ps22:16). One could wish that Sanders had chosen to explain aprophetic text such as Isa 52:13-53:12, the one most Christiansprobably would think of first, and which the NT writers use toexplain the sacrificial death of Jesus. Christians who believe andtreasure the OT prophecies concerning Christ's death are given littlehelp in reconciling these prophesies with Sanders's view. To explain

the relationship of the Crucifixion to texts long-claimed to prophesyChrist's death, he would probably appeal to his treatment of biblical

i i

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

12/34

142 TRINITY JOURNAL

Since human decisions were necessary to carry out Jesus' crucifixion,God could not know it until the human conspiracy was actually in

placethus God's resigned acceptance of it the night before ithappened.

What about NT texts that seem to say that God planned theCrucifixion before Creation? Passing over his odd reading of Rev13:8, let us consider his interpretation of Acts 2:23 and Acts 4:27-28.Concerning Acts 2:23"This man was handed over to you by God'sset purpose and foreknowledge"Sanders says,

It was God's definite purpose . . . to deliver the Son into the handsofthose who had a long track record of resisting God's work. Theirrejection did not catch God off guard, however, for he anticipatedtheir response and so walked onto the scene with an excellentprognosis (foreknowledge, prognsei) of what would happen, (p.103)

Though Acts 4:27-28 affirms that the conspiracy hatched by Herod,Pontius Pilate, the Gentiles, and the Israelites to crucify Jesushappened in accordance with what God's "power and will haddecided beforehand should happen," Sanders sidesteps this text,

simply noting the reference in his discussion ofActs 2:23.Before Sanders concludes his chapter on NT materials, he offersan extended excursus on divine predictions and foreknowledge (pp.129-37). As expected, he insists that the biblical portrait of God'spredictions and foreknowledge is best represented by "the present-knowledge model" (p. 130). So he concludes that there are threepossible explanations for divine predictions. First, "God can predictthe future as something he intends to do regardless of humanresponse" (p. 136), but this "does not require foreknowledge, only

the ability to do it" (pp.130-1). Second, "God may utter a conditionalstatement that is dependent on human response" (p. 136), but ofcourse, a conditional promise cannot be "genuine if God alreadyforeknows the human response" (p. 131). Third, "God may give aforecast of what he thinks will occur based on his exhaustiveknowledge of past and present factors" (p. 136), but such predictionsare always open to "the possibility that God might be 'mistaken'about some points" (p. 132).10 Sanders admits,

It may seem to proponents of exhaustive foreknowledge that the

explanations of various scriptural texts discussed above arestrained and unconvincing. But that is the way those who affirmpresentism regard the explanations offered by proponents of

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

13/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 143

We leave it to the reader to judge which view results in the greaternumber of strained and unconvincing interpretations.

D. Chap. 5: "Divine Relationality in the Christian Tradition" (pp. 140-66)

Sanders includes this chapter since it is important that anytheological proposal be consonant ''with the tradition" (p. 140). Hisreal concern is to argue that Augustine corrupted the early theologyof the Fathers, who, though they adopted "the vocabulary of Greekphilosophy," nonetheless attempted "to articulate what it means forGod to be the free Creator and the gracious Redeemer" (p. 146).

Sanders claims that the early church fathers believed that God "usesforeknowledge to see who will have faith and then elects those whowill," but Augustine "rejects such a belief for two reasons; hisanthropology and his doctrine of God" (p. 148). The problem withAugustine is that he "knows what is fitting for God to be {dignum

Deo) and uses this understanding to filter the biblical message" (p.149). Luther, the later Augustinian, comes under Sanders'sindictment because he follows this theology when he argues that"God's will is the sole reason for individual salvation." Lutherclaims that "human wills are so depraved that they cannot choosethe good, and thus God must choose for them" (p. 154). But it isCalvin who comes under Sanders's sustained heavy artillery (pp.155-7).

E. Chap. 6: "Risk and Divine Character" (pp. 167-207)

This chapter is rather dull because it repeats earlier data from hisoverview of the Old and New Testaments and arranges themaccording to his philosophical-theological framework concerning

divine attributes. He devotes thirteen pages to an excursus on divineomniscience, but Sanders argues that "the key issue is not the type ofknowledge an omniscient deity has but the type of sovereignty anomniscient God decides to exercise" (p. 195). So, he attempts tocajole advocates of "simple foreknowledge" to side with him againstthose who avoid "an omniscient God who takes risks" (p. 195). Thus,he repeats this claim of absolute disjunction: "Proponents of divinedeterminism hold that God never responds to creatures, whereasproponents of relational theism see God entering into genuine

personal relations with creatures" (p. 195). According to Sanders,only his kind of God can answer prayer, for "Only if God does notyet know the outcome of my journey can a prayer for safe traveling

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

14/34

144 TRINITY JOURNAL

for Providence" (pp. 200-6) at this conclusion. Thus, Sanders equates"the fellowship model" and "the relational model of God" with

"open theism" (see p. 207). He is determined to divide and conquertraditional theists by balkanizing Arminians, who hold to "simpleforeknowledge," against the Calviniste, who hold to "divinedeterminism."

F. Chap. 7: "The Nature ofDivine Sovereignty" (pp. 208-36)

If the previous chapter attempts to rescue the term "divineomniscience" from the accretions of determinism and various views

of foreknowledge, in this chapter Sanders beats back thosetheologians who "attempt to coopt the term sovereignty forthemselves, saying it can have only one meaningtheirsand thusdisqualifying from the discussion any position but their own" (p.208). One of those theologians, R. C. Sproul, claims, "If God is notsovereign, then God is not God" (p. 208).11 Sanders explains, "By

sovereign Sproul means exercising exhaustive control over everydetail that happens, and thus God by definition must exercise thissort of sovereignty" (p. 208). Now comes Sanders's coup de thtre,that is, his reversal of the charges. Sanders insists that it is not hisview, but the traditional view that diminishes God: "Such thinkerslimit God by asserting that God cannot decide which sort ofsovereignty to practice" (p. 208). It is not the God of those whobelieve in "specific sovereignty" who is truly free; he is bound andlimited by his inventors. It is the God of those who embrace "generalsovereignty" who is truly free. Sanders explains, "God is sovereignover his sovereignty and is thus free to choose what sorts of relationshe desires to create" (p. 211). Unlike those who insist that"sovereignty" must mean "exhaustive control" and impose upon

God their own "preconceived notion (dignum Deo)" of deity (p. 208),for Sanders, God had exhaustive sovereignty before he sovereignlychose to create relationships that limited him to exercise "generalsovereignty."

G. Chap. 8: "Applications to the Christian Life" (pp. 237-79)

This chapter sustains his absolute antithesis between his viewand the traditional view of God's providence, between "the risk and

no-risk, or relational and nonrelational models of providence" (p.237). He puts his view to the theological test of "adequacy to thedemands of life " He raises the questions:

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

15/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 145

What do these two models of providence have to say about sin,

grace and salvation? What insight do they give us into the problemofhuman suffering and into our experience ofevil? Are Christiansjustified in believing that prayers of petition make a difference toGod? Can we ever fail to understand God's guidance? (p. 237)

Briefly, on sin and salvation, the problem with Augustine and histheological heirs is that they believe, "Due to our sinful nature weare only free to sin. We can never desire God because our sinfulnature excludes such 'good' desires" (p. 238). For Sanders, adifferent view of sin and grace is in order.

Since its arrival on the scene, sin has become a universal humanexperience. Each of us grows up in relation to other sinners andsinful institutions and organizations. Socially, we are born into sin.Individually, we follow our forbears in sin. (p. 243)

He views "sin as the breaking of a relationship rather than as somesort of entity or condition" of the human heart (p. 251). So, Sandershas a problem with Calvin's view that "The very inequality

[distribution] of his grace proves that it is free" (p. 242). God freelygives his love and grace to whomever he wills, but "to say that Godgives his love freely does not require that God withhold it fromsome" (p. 242). Sanders contends that Augustine and Calvin "runtogether" the idea of free grace with the idea that grace is notdeserved (p. 242). Instead, God is like a human father whose love isproperly doubted if he should deny equal assistance forrehabilitation to his two drug-addicted sons (p. 242). UnlikeAugustine's God, who engages in "divine rape" by forcing his willupon the elect (p. 240), Sanders's deity gives "enabling grace" to

every human who has ever or will ever live (p. 245). "The love ofJesus elicits our loving response and motivates our imitation of hislove" (p. 246). Contrary to Augustine's view of God, Sanders arguesthat "God does not rape us, even for our own good. . . . God takesrisks with enabling grace in that people are not forced to believe" (p.246). His God only enters into a consensual relationship, and whenGod seeks our consent he always puts himself at risk because "it ispossible for us (however unreasonably) to refuse" (p. 246).

H. Chap. 9: "Conclusion" (pp. 280-2)

S d l d

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

16/34

146 TRINITY JOURNAL

no eternal blueprint by which all things happen exactly as Goddesires, (p. 280)

IIIA CRITIQUE

A. General Layout

Sanders's argument sometimes presumes greater understandingof terms, issues, and historical-theological knowledge than manyreaders may bring to it. Yet Sanders generally makes his pointsunderstandable and clear.12 However, the argument is so protractedand repetitive that many are likely to abandon the book. His fifty-sixpages of notes provide insight, for they indicate who his theologicalallies truly are; it is frequently non-evangelical theologians to whomhe appeals for support. Sanders places some of his more derisivecomments in the endnotes (e.g., p. 296 n. 131; p. 299 n. 6; p. 310 n. 79;p. 334 n. 61). He also buries in his endnotes questions that mightscandalize some readers.13

B. Derisive Sarcasm Against Traditional Theism

Only Sanders's sympathetic readers will not be put off by thesarcasm that runs throughout the book. For example, concerning"orthodox Christians" who "claim that biblical anthropomorphismsare 'accommodations' on God's part to our limited abilities tounderstand," Sanders responds, "Perhaps, but how do they knowthis is so? Have they found out the God beyond God?" (p. 33).Calvin, in particular, comes under sharp blows for his statement,

God is wont in a measure to "lisp" in speaking to us. Thus such

forms of speaking do not so much express clearly what God is likeas accommodate the knowledge ofhim to our slight capacity. To dothis he must descend far beneath his loftiness. (Institutes 1.13.1)

Sanders responds,

12There are, of course, some grammatical errors (pp. 35, 216) and an unusuallylarge number of printing errorsmisspelled words (pp. 56, 68, 331), missingcharacters (pp. 68, 111), missing words (pp. 68, 70,158), an incorrect verse reference(p. 83), an unfortunate double negative (p. 267).

l3For example, he comments: "Some people believe that Jesus could not havef il d hi [i h ild ] b h i G d Thi l i h i b d

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

17/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 147

Of course, those making such a claim were somehow able to

transcend their finite minds in order to know what God is reallylike. That is, they seemingly believed they could observe God usingboth lisping and normal discourse and were consequently able totell the rest of us which forms of discourse were accommodationsand which were literal. . . . I do want to point out that lurkingbehind the notion of divine accommodation seems to be the ideathat some people know for a fact what God is really like and arethus able to inform the rest of us . . . "duller folk" that we aremistaken, (pp. 33-4)14

Again, when Calvin explains that divine "repentance" is to be"takenfiguratively,"as "accommodation" by antiiropomorphism for"we cannot comprehend him as he is" (Institutes 1.17.12), Sanders isless than charitable with him by saying,

Of course, one may ask how Calvin acquired the correct knowledgeof the God beyond the scriptural revelation in order to know thatGod was accommodating himself to us. . . . [H]ow does Calvinknow, if not by divine revelation? If he claims it is taught inScripture, where does he get his criterion for claiming that texts

saying that God "will not change his mind" . . . refer to the wayGod really is, whereas texts saying that God "will change hismind" refer to the way God appears to be to us? (p. 156; italicsoriginal)

It does not seem to occur to Sanders that others could ask this samequestion of him when he claims, "Though God sustains everythingin existence, he does not determine the results of all actions orevents, even at the subatomic level" (p. 215). How did Sandersacquire such knowledge of God's activities at the "subatomic level"?But, more important, one should inquire how Sanders accounts forbiblical texts such as Prov 16:33, "The lot is cast into the lap, but itsevery decision is from the Lord" (NASB). Or, one could ask how heexplains that the random slinging of an arrow fulfills the prophesieddeath of King Ahab (cf. 1 Kgs 22:34; 22:28,38).

B. Misrepresentation ofTraditional Theism

Throughout his book, Sanders sets up an absolute antithesis that

misrepresents the views of those he opposes, for he reduces the

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

18/34

148 TRINITY JOURNAL

Augustinian-Calvinistic viewpoint to fatalism. It is apparentthroughout that he has an emotional aversion to any "no-risk" view

of God's providence. Thus, he claims theologians of the no-risk view"attempt to win the debate simply by definition," because as far asthey see it, "divine sovereignty can only mean exhaustive control ofall things" (p. 11). Sanders infers that these theologiansphilosophically forged their definition out of whole cloth and notout of Scripture. He chastens them, saying,

We have to observe what God has chosen to do in historybasedpreeminently on the history of Israel and Jesus of Nazarethratherthan simply define the type of sovereignty God must exercise, (p.

11)

Anyone who charitably reads the literature that has come fromthe pens of men such as Augustine, Martin Luther, John Calvin,Jonathan Edwards, R. C. Sproul, Paul Helm, D. A. Carson, JohnPiper, etc., also knows that while they talk about God's sovereigntyin exhaustive terms, they also speak of the significance andresponsibility of choice on the part of God's creatures, whetherangelic, demonic, or human. In fact, all these theologians carefully

insist that both propositions are true and must be affirmed withoutnullifying one or the other.15 Carson, for example, nicely lays out thetwo propositions:

1. God is absolutely sovereign, but his sovereignty neverfunctions in Scripture to reduce human responsibility.

2. Human beings are responsible creaturesthat is, they choose,they believe, they disobey, they respond, and there is moralsignificance in their choices; but human responsibility neverfunctions in Scripture to diminish God's sovereignty or to

make God absolutely contingent.16

Because Sanders will not say anything good concerning hisopponents' views, he insists on enforcing his absolute antithesis: onemust believe in Sanders's deity who is "relational" and takes "risks,"or one is left with only one other choice, which is a God who is"nonrelational," "manipulative," exercises "meticulous providence,"and "rapes" humans by forcing his will upon them. Thisexaggerated antithesis is present both in his arguments with his

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

19/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 149

opponents and in his handling of Scripture. To the latter we nowturn.

D. Inconsistency in Interpretation of Anthropomorphisms

Sanders complains that those he opposes misinterpret biblicalanthropomorphisms. They dismiss those that do not fit their ownview, labeling them as "mere anthropomorphisms" (e.g., pp. 52, 62,69, 72, 160, 187, 257). And they unfairly elevate otheranthropomorphisms to an elite status.

First, he believes that the metaphor of "God as king," has

dominated theology long enough (p. 11). It must be dethroned andreplaced with "the metaphor of God as risk taker." The hegemony ofthe royal metaphor must be shattered, and we need to open up "newways for us to understand what is at stake for God in divineprovidence" (p. 11). While Sanders properly recognizes that thevastness of God cannot be captured by a "single metaphor" (p. 72),he immediately asserts that one particular metaphor should berecognized as "a significant controlling metaphor in the biblicalnarrative" (p. 72). Which metaphor is this? It is "divine repentance."Why? Because it "is pervasive in the Old Testament" (p. 72). Butwhat has Sanders done? Has he not committed the same error forwhich he criticizes traditional theists? If they are guilty of readingthe biblical narrative through the narrow aperture of the royalmetaphor ("God as king"), Sanders is guilty of reading theScriptures through the single lens of his preferred "repentant God"metaphor ("God asrisktaker").

An illustration of Sanders's procedure is in order. Sandersalleges that traditional theists, particularly of the Augustinian-Calvinistic tradition, read the "potter" imagery "as a controlling

metaphor" in discussions that concern divine providence (p. 86).This is a disingenuous criticism coming from Sanders, for while hecharges that they are wrong to adopt the potter as the controllingmetaphor, he adopts his own controlling metaphor, arguing thattheirs has dominated "for so long in theology" (p. 11). He correctlyreminds us, "[I]n certain respects God canrightfullybe described asa potter, but God is not a potter in all respects" (p. 85). Here, Sandersquarrels with a strawman, for the best representatives of theAugustinian-Calvinistic tradition do not reify the potter imagery

(e.g., Isa 29:15-16; 45:9-13; Jeremiah 18) as he alleges. They do notread the metaphor to mean that because the clay represents people,h h i i tt l llifi d Th f ll P l' f h

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

20/34

150 TRINITY JOURNAL

like that of a potter and clay" (p. 86). But who among theologians heopposes has ever said it is?

Sanders rightly chastens any traditional theist who wouldelevate one biblical imagery to the level of "controlling metaphor" orto reify such a metaphor, but he fails to heed his own chastening, forhe imposes his preferred metaphor upon the biblical text as a gridthat controls what the text can say. He essentially admits this in theintroduction. He says,

I am examining providence through the lens of divine risk takingand am studying aspects of providence in order to see what shouldbe said concerning a risk-taking God. This will lead some readers

to judge the book "imbalanced." (p. 14)

Yes, it is imbalanced, because he has imposed his "God as risk-taker" motif upon the Bible. But not only does he force his "God asrisk-taker" grid upon the text, he also reifies his "controllingmetaphor" of divine repentance.

This raises his second concern with regard to biblicalanthropomorphisms. Sanders objects to traditional theists forbelieving that metaphorical descriptions of God, such as changes of

mind, "are not actually to be attributed to God" (p. 20). What hemeans is that they don't take anthropomorphisms literally, as hedoes. This is evident in his criticism of how "traditional theists"handle those biblical texts concerning God's "repentance" or his"change of mind." Sanders explains,

Claiming that biblical texts asserting that God "changed his mind"are merely anthropomorphisms does not tell us what they mean. If,in fact, it is impossible forGod to change his mind, then the biblicaltext is quite misleading. Asserting that it is a nonliteral expression

does not solve the problem because it has to mean something. Justwhat is the anthropomorphic expression an expression of? Thusclassical theists are left with the problem of misleading biblicaltexts, or, at best meaningless metaphors regarding the nature ofGod. (p. 69)

If Sanders had patience to read with charity Calvin's Institutes andothers with whom he disagrees, he would discover that they do not,in fact, assign biblical imagery concerning God "to the dustbin ofanthropomophism" (p. 68) or dismiss metaphor as "merelyanthropomophism" (p. 69) or simply assert that God's "repentance"is a "nonliteral expression" (p. 69).17 The problem is not theirs; John

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

21/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 151

biblical figures of speech must be taken literally. Note how Sanderslacks caution when he says,

Anthropomorphic language does not preclude literal predication toGod What I mean by the word literalis that our language aboutGod is reality depicting (truthful) such that there is a referent, another, with whom we are in relationship and of whom we havegenuine knowledge, (p. 25)

The word "literal" is a slippery term, which if not used carefullywill lead to confusion, at best, and to idolatry, at worst. DoesSanders mean "literal" as opposed to "not actual, not real?" Or does

he mean "literal" as opposed to "figurative"? He is confused. Hecorrectly states, "Metaphors do not provide us with an exactcorrespondence to reality, but they do provide a way ofunderstanding reality" (p. 72). However, while Sanders refuses toreify anthropomorphic ascription of eyes and hands to God, heequivocates when "repentance" is ascribed to God (p. 72). He clearlymoves beyond equivocation to reify or literalize anthropomorphismwhen he objects to the way John Calvin, Paul Helm, and Bruce Wareunderstand texts concerning God's "repenting" (as in 1 Sam 15:11,

29, 35). Sanders objects, "On what basis do these thinkers claim thatthese biblical texts do not portray God as he truly is but only God ashe appears to us?" (p. 68, italics added). Does he mean to say thatGod really does repent? Yes, that is exactly what he means, becauseunlike those thinkers, Sanders will not treat the words as "merelyanthropomorphisms" (p. 69). He confidently asserts, "If, in fact, it isimpossible for God to change his mind, then the biblical text is quitemisleading" (p. 69). Sanders makes anthropomorphic "repentance"portray God as he really is.18 Sanders does not realize that he has

reified metaphors and anthropomorphisms concerning God, despitethe fact that he says, "It may be objected that divine repentance isliterally impossible, since God has exhaustive foreknowledge offuture events" (p. 73, italics added). Because he regards "divinerepentance" to be a major "controlling metaphor" throughout thebiblical narrative (p. 72), as a matter of course, Sanders takes "divinerepentance" to portray God as he really is (pp. 75,77). Therefore,

If God decides to disclose himself to us as a personal being whoenters into relationship with us, who has purposes, emotions anddesires, and who suffers with us, then we ought to rejoice in thisanthropomorphic portrait and accept it as disclosing to us the very

t f G d ( 38 it li dd d)

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

22/34

152 TRINITY JOURNAL

Sanders is rather inattentive concerning his use of the termliteral. But to be fair, it does not appear that he is disingenuously

exploiting the slipperiness of the term "literal." It appears morelikely that he is sloppy in his use of "literal," for he is unaware thathis own explanation of figurative language concerning God actuallymigrates from his mild disclaimer that metaphors do not provide"an exact correspondence to reality" (p. 72). He contrasts his readingof anthropomorphisms with that of those he opposes. While theythrow them onto a scrapheap (p. 68), John Sanders believes "allbiblical metaphors are to be taken seriously" (p. 72, italics added). Itis evident that "seriously" is, for Sanders, another word for

"literally." Sanders confuses these two terms throughout the book.For example, he insists that "the Bible does not need to be read as atwo-layered cake with the top layer representing how God appearsto us . . . and the bottom layer representing how God really is" (p.187). Interpreted, this means, "There is no need to dismiss as mereanthropomorphisms the texts in which God plans, repents, changesin his emotional state, anticipates or is surprised at our sinfulresponse" (p. 187). Then, without any indication that he realizes thathe has reified metaphors and anthropomorphisms, Sanders says,"They are metaphors that reveal the kind of God who addresses us"(p. 187).

So, against traditional theists who understandanthropomorphism to provide an accommodating glimpse of God whocondescends in love as an actor in his unfolding drama ofredemption, Sanders understands such figures of speech as "divinerepentance" to portray God as he actually is. In this, he and his fellow"open theists" have followed the lead of Clark Pinnock, whoreasons, "According to the Bible, God anticipates the future in a way

analogous to our own experience" (italics added).19 They have inverted

the imago Dei. While the biblical text insists that humans areanalogous to Godman was made in God's imageSanders and"open theists" insist that God is analogous to humansGod exists inman's image.20 For "open theists," human qualities become the pointof reference by which they understand and measure God.

Sanders's interpretation of 1 Samuel 15 is unpersuasive. Thestory of Saul's demise as king over Israel explicitly disallows hisexplanation of the two times God is said to "repent." The storyincludes v. 29 for the express purpose of proscribing a childish and

irreverent reading which might presume that the anthropomorphiclanguage of vv. 11 and 35 portray God as he actually is. OverSanders's intense objections 1 Sam 15:29 makes this ab ndantl

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

23/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 153

clear, for the text reads, "He who is the Glory of Israel does not lie orchange his mind; for he is not a man, that he should change hismind" (NIV). This text warns Sanders not to do the very thing hedoes. It warns him not to reason, "When the text uses the same verbin verses 11 and 35 to say that 'God regrets/ the text means that Godreally does change his mind." Contrary to Sanders, 1 Sam 15:29 must

be taken in the most comprehensive sense as an assertion aboutwhat the God of Israel is always like (see p. 69). To read the text likethis is not a "disparagement of anthropomorphism," as Sandersclaims (p. 20). Nor does such a reading "describe an abstracttranscendence" (p. 22). The verse expressly characterizes the God of

Israel as one who, under no circumstances either "lies" or "changeshis mind."

21

E. Imposition ofHisOwn Dignum Deo on the BiblicalPortrayalofGod

Sanders repeatedly censures his opponents, such as Augustine,for assuming "what is fitting for God to be (dignum Deo)"and thenuses this understanding "to filter the biblical message" (p. 149). Heargues that such theologians are saying in effect, "Any God worth

his salt must conform to our intuitive notions of deity or get out ofthe deity business" (p. 33). If this is an error for Augustine andCalvin, is it not an error when Sanders uses his own dignum Deo as alens through which to read the Bible, fitting everything into his own"preconceived notion" of what deity must be like (cf. p. 208)? Hecorrectlynotes, "When we read the Scripture through the lenses ofcertain models, we tend to interpret Scripture from that perspective"(p. 16). Sanders wants readers to believe that his view of God as"risk taker" emerges from the pages of Scripture.

22Yet, at the same

time he admits, "I am examining providence through the lens ofdivine risk taking" (p. 14). Should Sanders be exonerated for doingthe very thing he reprimands in others? Is Augustine's error to use areading lens, or is it failing to admit, as Sanders does, that he uses areading glass? One could point to numerous examples todemonstrate how Sanders imposes upon the biblical text his "opentheist" view of what God must be like (dignum Deo). To do so wouldinflate this critique to book-length. Four categories of evidence mustsuffice.

1. Inconsistent Concerning Anthropomorphisms

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

24/34

154 TRINITY JOURNAL

arms, etc. to God? Why not literalize a metaphor that portrays Godas a father? Is it not because there are verses which affirmgeneralized principles that prohibit such an error? God who madethe heavens and earth is not in need of food, though he speaks withhis mouth. He does not eat the animal sacrifices required of thepeople (Ps 50:1-13). The Lord who made the heavens and earth everkeeps watch over his people as a watchman. Yet, his eyes do notgrow weary and close in slumber, nor does he refresh himself withsleep (Ps 120:2-4). God who sits enthroned upon the heavens is like afather who has compassion on his children. Yet, he is not like manwho flourishes and quickly fades away (Ps 103:13-19). All these

passages that use anthropomorphic language concerning Godinclude sufficient information, though not always explicit, to quashreification of the imagery. Certainly, it is not merely because John4:24 declares, "God is spirit" that Sanders does not actualizeanthropomorphisms concerning eyes, ears, and hands. If Sandersinsists upon a literal reading of anthropomorphisms "in texts inwhich God plans, repents, changes in his emotional state, anticipatesor is surprised at our sinful response" (p. 187), why is he notconsistent? He is sure that Genesis 22 means that "God genuinely

does not know" whether or not Abraham trusts him (p. 52). Why notthen be honest and admit that God not only does not know thefuture free acts of creatures, but that he also does not know some ofthe present secrets in human hearts? If God "does not know"something, the present, and not just the future, is involved. Also,why not be consistent and read God's anthropomorphic question,"Adam, where are you?" (Gen 3:9; cf. vs. 11), to indicate that Goddoes not know at least some things that are in the present?Furthermore, why not read Gen 18:20-21 in the same way? The Lordtells Abraham, "The outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah is so greatand their sin so grievous that I will go down and see if what theyhave done is as bad as the outcry that has reached me. If not, I willknow." If Sanders is going to insist that his reading of biblicalanthropomorphisms is consistent, then he must believe that Goddoes not have present knowledge of the affairs in Sodom, for Godwas only basing his present knowledge on reports. Thus, God has tofind out what is now happening in Sodom. God doesn't know untilhe goes down there. Open theists dare not be consistent with suchtexts, because to be uniform necessitates that they admit that there

are some things that God does not presently know.

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

25/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 155

knowledge (Isa 40:13-14), who ordains all things that come to pass(Eph 1:11), who declares things before they come to pass (Isa 41:26),who purposes to do whatever he desires with no one having thepower to thwart his intentions (Ps 115:3; Isa 14:27; Dan 4:35), whoordains the most fortuitous events, including lots or dice (Prov16:33), who determines when even a sparrow should fall to theground or a hair should be uprooted from the scalp (Matt 10:29-30).Second, Christians have also read in the Bible that God discloseshimself as a person who relates to his creatures, who inquires whereAdam is located, who tests Abraham, who is grieved overwickedness, who repents that he has made Saul king, who becomes

incarnate as a man. Anthropomorphism and metaphor are crucial,for they disclose things about God that we would not know withoutthem, qualities that we must factor in to our affirmations concerningGod. Sanders virtually ignores the first set of passages as heconcentrates his efforts upon the latter. Though he honestly believesthat his theological opponents have nullified this second set ofpassages with the first, it is he who has done the converse. This isirresponsible. Those against whom Sanders so vigorously fightshave devoted much of their lives attempting to handle these two

biblical themes responsibly and even-handedly.

3. Restrictions On Texts That Speak OfGod's General Acts

If Sanders restricts the "pancausality" passages, which speakgeneral language concerning God within a given historical context,why not restrict every portrayal of God to a specific historicalcontext, since all Scripture is historically conditioned? When Sandersdismisses the prophet's question, "When disaster comes to a city,

has not the LORD caused it?" (Amos 3:6), he must be governed bytheological prejudice, for the whole context is full of generalized, nothistorically specific, cause-effect relationships. Consider alsoJeremiah's words: "Who can speak and have it happen if the Lordhas not decreed it? Is it not from the mouth of the Most High thatboth calamities and good things come?" (Lam 3:37-38). Sanders hasto oppose the obvious generalized meaning of the text, for otherwisehis whole case shatters. Like a child who covers the eyes todisappear, Sanders supposes that restricting these passages tospecific historical contexts protects God from being involved incalamity in general (see pp. 83-4,121). But don't these texts still saythat God caused the calamity? Not according to Sanders. The texts

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

26/34

156 TRINITYJOURNAL

Sanders exhibits linguistic deficiency. In his attempt to salvage hisrestrictive view that God has only present and past knowledge, hecommits two fallacies in interpreting the root in John'sgospel. He presumes that the etymology of the word establishes themeaning (the root fallacy), and he prescribes that one meaning("hand over") to every use of the word (the prescriptive fallacy) (pp.98-9). He indulges in semantic anachronism by imposing the currentEnglish use of prognosis upon Luke's use of the Greek word? in Acts 2:23. Sanders also commits the prescriptive fallacywith regard to the use of the three words Qcabed, hazaq, and qashah) todescribe God's "hardening" of Pharaoh's heart. He reasons that

because the Hebrew words could mean "to make something strong"(p. 59), that this is what the words mean in every context. Thus,"God strengthened Pharaoh's heart" (p. 121). Furthermore, Sandersrequires too much of conditional language throughout the Bible.Without showing any reflection on traditional accounts ofconditional or contingent language in the Bible and how it relates toGod, he uncritically quotes Terence Fretheim, who claims that "if"necessarily "implies a somewhat uncertain future'" (p. ).

23Later

Sanders claims, because God says through the prophet Jeremiah, "if

you repent then I will let you remain in the land" (Jer 7:5-7), "Such'if languagethe invitation to changeis ingenuine if God alreadyknew theywould not repent" (p. 74). Conditional language in itselfcannot properlybe taken to infer uncertainty or certainty, either forhumans or for God.

24While it is entirely true that the events God has

ordained to come to pass are conditional (that is they are ordered ina cause-effect relationship), God's planning of the events is notconditional. That is, his act of foreordaining is not conditioned by thethings he decreed, but the things he decreed are conditioned upon

the occurrence of their causes. This is so because for everyconditioned event, God's foreordination equally determined thecause as well as its effect.

^Note Sanders's absolutist reasoning concerning Pharaoh. "That the divinestrengthening leaves Pharaoh with alternatives is indicated by the conditionallanguage employed in [Exod] 8:2, 9:2 and 10:4. God proclaims that particular

judgments are coming ifPharaoh does not release the people. If, however, Pharaoh isso under divine control that he cannot let them go, then God's use of if isdi i f th f t i t B tt i diti l G d i i t

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

27/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 157

E. Contradictions In His Use OfTheological Argument

Sanders's dislike of Augustinianism and Calvinism appears toprompt some contradictions, such as when he disallows certaintheological distinctions to Calviniste that he himself appropriateswhen he needs them. Two examples stand out.

1. No Secondary Causes?

Compatibilists have long insisted that God employs means or

secondary causes to accomplish his ordained purposes. Because he isso intensely driven by his notion of "libertarian freedom/' Sandersrejects the idea of "secondary causes." He claims,

Calvin seeks to deflect the charge that God is then responsible forsin by defining human freedom in compatibilistic terms and bymaking use of the Scholastic notion that God worked throughsecondary causes. As long as God does not directly determineevents but only establishes the causes by which they come about,God is thought to be absolved of blame, (p. 155)

This statement is remarkable for two reasons. First, the latterstatement shows that Sanders does not accurately understandCalvin's view. For Calvin had no problem affirming that God in factpredetermined the Crucifixion; God planned both the event and thecauses of it. Yet, because God ordained that secondaryagentsHerod, Pontius Pilate, the Gentiles, and Israelites (Acts 4:27-28)should conspire to murder his Son, God is not culpable for thecrime. Second, Sanders finds it necessary for himself to retreat to the

same concept. Early in the book, as he works with biblical texts,Sanders tries to explain how future events said to be definite canagree with "open theism." He explains, "Texts indicating that afuture event is definite suggest that either the event is determined byGod to happen in that way or God knows the event will result from

a chain ofcausal factors that are presently in place" (p. 75, italicsadded). How does his appeal to "a chain of causal factors" differfrom the compatibilist's idea of "secondary causes"?25

^ h i s causes a theological dilemma for Sanders's view of a God to whom thefuture is open. This is so because if Sanders admits that anything in the future is

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

28/34

158 TRINITY JOURNAL

Yet, even after he makes this semi-veiled appeal to "secondarycauses," he repudiates the idea of "secondary causes" again only

seventeen pages later. When it is both convenient and necessary tomake a distinction concerning causation, Sanders adopts thecompatibilist's idea of "secondary causes," but he does so with a thinveil by assigning a different name to it. So when he responds to PaulHelm's charge that any who believe that one's salvation is based onan act of free will has grounds for boasting before God, Sandersanswers with a distinction

between the complete cause and the most significant cause. For

instance, if an arsonist uses gasoline in setting fire to a building,then gasoline and combustible material are certainly causal factorsin the fire. In the moral realm, however, we would look for themost significant cause and that would be the arsonist. God isclearly the most significant cause, but not the complete or solecause, of the personal relationship, (p. 247, italics added)26

Sanders, then, does distinguish between God's action and humanaction. But by using his designationscomplete cause and most

significant causehe assigns too much to humans and too little to

God and does not escape Paxil Helm's criticism.

2. Providence and Egalitarianism

Not only does Sanders reject Calvin's appeal to "secondarycauses" and then use the same basic distinction for his ownadvantage, he also refuses Calvin's "non-egalitarian" argumentconcerning divine providence and then uses it for himself, again,when it is advantageous. Calvin argues against the pagan notion

that things happen by chance, without divine causation (Institutes1.16.2-3). Sanders summarizes Calvin's claim: "

In life one person escapes shipwreck and another drowns; one isrich and another is poor; one mother has abundant breast milk andanother has hardly any. Calvin says that all these circumstances areexpressly arranged by God for some reason, (p. 212)

occasion, how does open theism escape the very charges they throw at classicaltheism, whether ofthe Arminian or Calvinist variety?^He appeals to J. R. Lucas's distinction between "complete cause" and "most

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

29/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 159

In other words, Calvin argues that one must not reason that becausethings appear to happen fortuitously and not with egalitarian equity

then God did not ordain all things. While Sanders refuses Calvin anyuse of this argument, he reserves the right to use it when it isexpedient. He challenges Gordon Kaufman's view that God does notdo any special acts in human history. Sanders claims,

What Kaufman and others really want is a uniform code ofegalitarian relations that God must follow. . . . But we have nogrounds for believing that a personal God is under some obligationto ensure total equality for us regarding life's circumstances.Moreover, no human has any sort of claim or right to a special act

of God. Nevertheless, in my opinion, God is much more active thanwe can ever identify. But most of his worklike most of aniceberggoes largely unseen. Theists simply do not know all thereasons behind God's actions, such as why God may act in onesituation for one person but not, insofar as we know, in anothersituation for someone else. Does this imply God's acts arearbitrary? In order to establish arbitrariness we would have to haveaccess to all of God's knowledge and intentions. Critics such asKaufman utilize the principle of egalitarianism in order to rule outany possibility of divine action and so opt for some form of deism.

Those who affirm a personal God who interacts with us will preferto live with the uncertainty of knowing why God does some thingsand not others. Admittedly, that God does some things and notothers means that providence is not run on a purely egalitarianbasis, (p. 261)27

How can Sanders refuse Calvin the same basic argument heemploys? Three reasons seem apparent. First, Sanders is concernedto preserve his view of "God as personal." He believes that Calvin,like Kaufman, holds to an impersonal God, though one is virtually afatalist while the other is a deist. Second, Sanders fails to realize thathe is using Calvin's argument, simply applied to a differentopponent of Christian faith. Third, though Sanders's "open theist"view of God is very defective, he actually mounts a traditionalist andorthodox apologetic defense of the biblical doctrine of God'sprovidence, not realizing that it agrees with Calvin's. Here,compatibilists should rejoice over Sanders's inconsistency.

27Ironically, Sanders's response goes against his own use of this same argument

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

30/34

160 TRINITY JOURNAL

F. A Challenge To The FoundationalBelief Of Christianity

Because the Cross is central to the Christian faith, it is necessaryto point out the gravity of what Sanders is arguing. He plainlyaffirms that God the Father and God the Son did not plan theCrucifixion before creating all things. Rather, they both came torealize, that dark night in Gethsemane, that there was no alternativeleft "for this historical situation" (p. 100). One could wish thatSanders would reflect a bit more on biblical texts and be morecautious when speaking of the Cross of Jesus Christ. As he strives tobe consistent within his theological commitments, he unfortunatelychallenges the heart of Christian faith. Apart from God's purposedintention to crush his own Son as the substitute who took uponhimself "our transgressions" and "our iniquities" (Isa 53:5-6),Christ's death is a pointless tragedy. D. A. Carson has wiselyobserved,

If the initiative had been entirely with the conspirators, and Godsimply came inat the last minute to wrest triumph from the jaws ofimpending defeat, then the cross was not his plan, his purpose, thevery reason why he had sent his Son into the worldand that is

unthinkable. . . . Christians who may deny compatibilism on frontafter front become compatibilists (knowingly or otherwise) whenthey think about the cross. There is no alternative, except to denythe faith.28

It is lamentable that Sanders does not back away from this precipice.After referring to the Cross as a divine "gambit," Sanders backs

away from attempting to explain the significance of the Cross,saying, "There is profound mystery in what God was doing on thecross, and I do not pretend to understand it" (p. 104). Nevertheless,

he explains, "First, I understand sin to primarily be alienation, or abroken relationship, rather than a state of being or guilt" (p. 105).With such an understanding of humanity's plight, his explanation ofthe Cross predictably falls short of biblical descriptions. He says,"The cross did not transform the Father's attitude toward sinnersfrom hatred to love. The Father has always loved his creaturesinspite of sin" (p. 104). So, when Sanders goes on with his attempt toexplain the significance of the Cross for God and humanity, he doesso without a hint of divine wrath, without any allusion to God's

justice, and with no clear indication of substitution. The most onecan charitably conclude from his discussion is that the Cross ofCh i t i b t i d i t f Ab l d' " l i fl " th

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

31/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 161

G. "Loaded" Language

Whenever Sanders represents Calvinism or compatibilism, heuses highly charged statements with associative significance. Heapparently wants to influence his readers to reject the view he scornsand to accept his "open theist" view of God. The compatibilist's Godis "impersonal" and "manipulative" (p. 215). This God engages in"meticulous providence," for he cannot bear to have creatures whohave "libertarian freedom" (p. 215). Sanders claims that those whohold the "no-risk view" do not believe in the sovereignty of

Godthey hold to "specific sovereignty" or worse, "themanipulative view of sovereignty" (p. 279). Such a view of Godnecessarily implies "a great deal of manipulation of humans" (p.277), because that God is a "nonrelational" deity (p. 237). Such a"God never responds to creatures," but the God of "relationaltheism" enters "into genuine personal relations with creatures" (p.195). No wonder, then, those who hold such a view of God are alsoimpersonal and cold: as Sanders characterizes them, "Forproponents of specific sovereignty there is no such thing as anaccident or a genuine tragedy" (p. 212). Their God "micromanages"

human events (p. 235). Not only is the "no-risk" God who exercises"exhaustive sovereignty" (p. 240) unworthy of human love, he also"is incapable of receiving our love because God is impassible andwholly unconditioned by us" (p. 247). Such highly chargedstatements punctuate Sanders's whole book.

Thus, to Sanders, the God of Augustine, Luther, Calvin, andtheir theological descendants is just as much a counterfeitrepresentation of the God of the Bible as is the God of processtheism. He says,

Such distorted images of omnipotence end up with a loveless power.God is the powerful, domineering Lord who always gets preciselywhat he wants. In contrast to this is process theism's God of

powerless love, who is impotent to act unilaterally in the world in theways depicted in Scripture, (p. 190)

He argues, if readers repel process theism, they ought to repeltraditional theism with equal repugnance.

One simply cannot have it both ways: either God controlseverything and the divine-human relationship is impersonal, or

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

32/34

162 TRINITY JOURNAL

God of sheer omnipotence can run a world of exhaustivelycontrolled beings. But what is magnificent about that? (p. 215)

It is one thing to admit one's perplexity concerning how God can beabsolutely sovereign over his creatures without, at the same time,nullifying their accountability. Paul acknowledges this difficultywhen he says,

One ofyou will say to me: "Then why does God still blame us? Forwho resists his will?" But who are you, O man to talk back to God?"'Shall what is formed say to him who formed it, "Why did youmake me like this?'" (Rom 9:19-20)

Sanders affirms that when the compatibilist's God saves peoplehe engages in

divine rape because it involves nonconsensual control; the will ofone is forced on the will of the other. Of course, the desire Godforces on the elect is a beneficent onefor their own goodbut it isrape nonetheless, (p. 240, italics added)

A charitable reader will wince at these words and may even absolve

the author for momentary excess, but Sanders presumes upon suchcharity for he exploits this deplorable image twice more (p. 246).Later he repudiates Calvin's distinction between "remote cause" and"proximate cause" by saying,

Ifa child is raped and dismembered, there is a human agent who isthe proximate cause, but God is the remote cause. The rapist isdoing specifically what God ordained him to do. Hence the humanagent is the immediate rapist and God is the mediate rapist, (pp. 255-6, italics added)

Here Sanders blatantly caricatures the God whom Christiansthroughout the centuries have embraced by faith and worshiped.Does Sanders represent his "open theist" associates as a spokesmanwhen he speaks like this? If so, are John Sanders, Clark Pinnock,Greg Boyd, David Basinger, and William Hasker consistent whenthey say that the traditional view of God which they oppose is partof orthodoxy? How can a God who is manipulative, micromanaging,non-relational, coercive, who forces his will upon people without

consent, yes who is a rapist, be tolerated by any open theist? Howcan such a deity be accepted by anyone? It is unconscionable and

thi k bl f th t d th t b li f i h G d i

-

7/31/2019 Putting God at Risk--A Critique of John Sanders's View of Providence

33/34

CANEDAY: PUTTING GOD AT RISK 163

IV. CONCLUSION

Many readers will cast The God Who Risks aside. Some will do soout of apathy, others out of uneasiness lest their faith fail, and othersout of disgust with the view of God presented by Sanders. To thedegree that Sanders arrests any whose excessive zeal for Calvinismcauses them to slip into a kind of fatalism, may God be praised evenfor using this book for such good. However, others will be attractedto accept Sanders's view of God. Two kinds of people are especiallyvulnerable. Many college students whose Christian beliefs are not

yet grounded but who already are asking the questions John Sandersraises and attempts to answer are prime targets for this book.Likewise, many who, after experiencing deep tragedies such as JohnSanders did with the accidental death of his brother, may teeter onthe brink of despising God. They are likely to find Sanders'sexplanations to be a way out of their dilemma, a dilemma that findsthem caught between despising the God who orders all things, eventragedies, and wanting desperately to retain something of their faith.Here is the great danger of Sanders's book. He puts God at risk forthese people. Yet no personal loss, however tragic, truly compares

with the murderous plot to which God's Son submitted when heoffered himself as the acceptable sacrifice to avert God's wrath fromhis people. At once the Cross and the participants were ordained byGod and the players conspired against God's Anointed One (Acts4:27-28). If anyone follows Sanders's guidance fully on how tounderstand such events, one jeopardizes faith in the God of theBible.