Ptosis' · Ptosis FIG. 2. Apatienit with moderate left ptosis andleft hemiparesis. moderately...

Transcript of Ptosis' · Ptosis FIG. 2. Apatienit with moderate left ptosis andleft hemiparesis. moderately...

Journial of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 1974, 37, 1-7

Ptosis'

LOUIS R. CAPLAN2

From the Stroke Service of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Mass., U.S.A.

SUMMARY Twenty-five examples of ptosis occurring with an acute stroke are analysed. Thirteenof these patients had hemispheral infarctions in which ptosis could not be explained by third nerveor sympathetic dysfunction. The ptosis in these 'cerebral' cases was bilateral, with other factors suchas pyramidal tract damage determining the asymmetry of the ptosis. In some patients, the eyelid wasptosed on the side of a hemiparesis, narrowing the palpebral fissure. The anatomical basis for this isprobably damage to pyramidal neurones or their fibres. The 10 cases of ptosis in relationship tobrain-stem infarction included two patients with isolated complete ptosis in one eye in associationwith a contralateral third nerve palsy.

Eyelid ptosis, a common neurological sign, isclassically explained by weakness of the levatorpalpebrae superioris muscle due to oculomotornerve disturbance, or by weakness of Muller'smuscle secondary to involvement of its sympa-thetic innervation, or by intrinsic disorders ofthe lids and their musculature. A less knownform is 'cerebral' ptosis which occurs in associa-tion with hemispheral lesions (Marquez, 1936;Cogan, 1956; Walsh and Hoyt, 1969). Most ofthe reported cases of cerebral ptosis have been inpatients with brain tumours, with the ptosishaving been attributed to pressure on the brain-stem, third nerve, or sympathetic nerves.The present report had its origin in the observa-

tion that in some patients with hemiparesis due tohemispheral infarction, ptosis was noted whichwas not readily explained by either a third nerveor sympathetic paralysis. Twenty-five consecu-tive cases of ptosis of recent origin from theStroke Service of the Massachusetts GeneralHospital have been studied and analysed. Thesecases were seen within a nine month periodduring which 284 stroke patients were examined.Thirteen cases qualify for 'cerebral' ptosis, and10 had a lesion in the brain-stem. Two patientshad ptosis as part of a Horner's syndrome relatedto local disease of the carotid artery. All patients

Work supported by a NINDB Special Fellowship Grant no.1 F 11 NS 2241-01-NSRA.2 Address for reprints: Dr. Louis R. Caplan, Neurology Service, BethIsrael Hospital, 330 Brookline Avenue, Boston, Mass. 02215, U.S.A.

1

were examined three or more times during theacute phase of their strokes. Drowsy patientswere excluded. The inclusion only of alertpatients with vascular disease minimized the roleof pressure phenomena.The findings proved to be somewhat complex

in so far as ptosis was present in some cases onthe hemiparetic side, in others on the non-paralysed side, and in still others bilaterally.The need to be precise in the selection of casesrequired that the term ptosis be defined for thepurposes of the study. This was not simple, forno definition that included measurable criteriacould be found in the literature. Therefore thelids of 20 control patients were examined inorder to determine the range of normal lidmeasurements.

RESULTS

1. CONTROLS The control group, selected ran-domly from the medical wards, had an averageage of 66 years, identical with that of the strokegroup. Figure 1 depicts the measurementsutilized with the patient fixing gaze straightahead. The vertical height of the upper eyelidranged from 2-12 mm. The palpebral fissurevaried from 6-12 mm with no definite inverserelationship to the lid height. The diameter of thecornea was relatively uniform at 12 mm (varyingfrom 115 to 12-5 mm). In 19 of the 20 controls,the upper lid covered less than 4 mm (one-third)

Protected by copyright.

on February 25, 2020 by guest.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.1.1 on 1 January 1974. Dow

nloaded from

Louis R. Caplani

TABLECLASSIFICATION OF CASES

FIG. 1. Measurements of lid and palpebral fissure.1. Vertical height of upper lid. 2. Diameter of cornea.3. Palpebral fissure.

1. Cerebrala. Hemisphere or pyramidal tract infarction with unilateral ptosis

on the hemiparetic side (6)(3) Embolic infarction in middle cerebral artery territory(2) Pure motor hemiparesis, lacunar infarction(I) Internal carotid artery stenosis

b. Hemtsphere lesion with bilateral ptosis, more severe on thehemiparetic side (3)(1) Anterior cerebral artery occlusion(I) ? slit haenmorrhage, posterior hemisphere

c. Hemisphere lesion with bilateral prosis, less on the hemipareticside (2)(2) Bilateral cerebral infarction, old and recent

d. Hemisphere lesion with unilateral ptosis on the non-hemipareticside (2)(2) Unilateral embolic cerebral infarction

e. Internal carotid artery occlusion with ptosis ipsilateral to thleocclusion as a part of a Horner's syndrome (2)

2. Brain-stemita. Part of a Horner's syndrome (6)

(2) Lateral medullary infarction(1) ? embolus to the top of the basilar artery(3) Basilar occlusion or branch occlusion with pontine infarc-

tionb. Unilateral ptosis on the hemiparetic side WvithouLt pupillary

change (1)(I) Medial pontine syndrome

c. Bilateral complete ptosis (3)(3) Rostral brain-stem infarction

of the cornea. In the exception, the patient had aneurological lesion. From these findings, thefollowing criteria were derived to define ptosisacquired during an acute stroke.

1. Drooping of the upper lid to cover one-third (4 mm) or more of the cornea.

2. A vertical measurement of the lid more than8 mm.

3. A definite increase in eyelid droop com-pared with the previous state, according torelatives, friends, a physician, or a photograph.

Slight degrees of ptosis have been excluded bythese criteria. Ptosis was called 'mild' if it metthe above criteria, 'moderate' if the lid coveredmore than one-half of the cornea, and 'severe'if the palpebral fissure was nearly closed by thedrooped lid.

2. CEREBRAL (HEMISPHERAL) a. Unilateralptosison the side of hemiparesis (six cases) Three ofthese patients had the sudden onset of contra-lateral hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, andhemianopsia with aphasia or apractagnosia.Two of these three patients had a recent myo-cardial infarction; one had mitral stenosis, andall were thought to have had middle cerebralemboli. Two of the other patients fulfilled

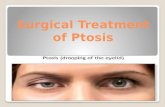

Fisher's criteria for pure motor hemiparesis,indicating a lacunar infarction (Fisher andCurry, 1965). One patient had a slight righthemiparesis and aphasia due to severe stenosis ofthe internal carotid artery at the syphon. Fourpatients in this group had mild ptosis, and intwo others the ptosis was moderate in degree(Fig. 2).

In these cases the palpebral fissure was muchnarrower on the side of the facial paresis, a find-ing that runs counter to the usual teaching thatit is wider on that side. Since this type of ptosisoccurred both in large hemispheral lesions and inlacunar cases in which the infarct lies in theinternal capsule, the responsible insult probablyinvolves descending suprasegmental upper motorneurone pathways.

b. Bilateral ptosis, greater on hemiparetic side(three cases) One patient had an angio-graphically demonstrated anterior cerebral arteryocclusion with left lower extremity and shoulderparesis but no facial weakness. The second hadheadache, left hemianopsia, left hemisensoryloss, bloody spinal fluid, focal seizures, and a

2

Protected by copyright.

on February 25, 2020 by guest.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.1.1 on 1 January 1974. Dow

nloaded from

Ptosis

FIG. 2. A patienit with moderateleft ptosis and left hemiparesis.

moderately severe left facial paresis. All of thephysical signs remitted within a week except forthe facial paresis and ptosis. The lesion wasthought to be a subcortical haemorrhage in theposterior right hemisphere. The third case had anangiographically demonstrated left internal caro-tid artery occlusion with severe aphasia andright hemiplegia. These were considered examplesof bilateral cerebral ptosis in which the ptosiswas accentuated on the side corresponding tothe pyramidal tract deficit. The three patientsall had ptosis of moderate severity.

c. Bilateral ptosis, less on hemiparetic side(two cases) Both patients had a history of anold hemiparesis that had cleared and suddenlydeveloped a hemispheral lesion in the previouslyuninvolved hemisphere. Neither had ptosis as aresidue of their first stroke. Each patient had asevere facial paresis, and mild ptosis on thehemiparetic side and severe ptosis on the non-hemiparetic side. These were believed to be casesof bilateral cerebral ptosis in which a widerpalpebral fissure occurred on the side of thehemiparesis.

d. Unilateral ptosis, oni non-hemiparetic side(two cases) One patient with rheumatic heart

disease and documented bacterial endocarditisand aortic insufficiency suddenly developed a lefthemiplegia and left hemisensory loss. The secondpatient had a cardiac pacemaker and suddenlydeveloped a right hemiplegia with aphasia. Bothwere diagnosed as embolism to a cerebral hemi-sphere. Each had moderate ptosis on the normalside, and a severe facial paresis contralaterally.These were also believed to be cases of 'bi-lateral' cerebral ptosis (as described in (c) above)in which the widened palpebral fissure on thehemiparetic side had completely obscured theptosis on that side.

e. Homner's syndrome on non-hemiparetic side inrelationship to ipsilateral internal carotid arteryocclusion (two cases) Two cases had mildptosis and miosis on the side of an occludedcarotid artery. One internal carotid artery wasoccluded at the common carotid artery bifurca-tion in the neck; the other had an occlusion ofthe internal carotid artery at the syphon withretrograde extension of the clot into the neck.Each patient had a severe hemispheral deficit.

3. BRAIN-STEM a. Complete bilateral ptosis(three cases) Two of these patients had a com-plete third nerve paralysis on one side, while on

3

Protected by copyright.

on February 25, 2020 by guest.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.1.1 on 1 January 1974. Dow

nloaded from

Louis R. Caplai

the other side complete ptosis occurred in isola-tion and was not accompanied by any othersigns of third nerve deficit. These three casesprobably had midbrain infarction and representexamples of the 'syndrome of the mesencephalicartery' recently reviewed by Segarra (1970).

b. Ptosis on side of hemiparesis (as in 2a) (onecase) This patient, a diabetic lady, awakenedwith a right hemiparesis, left intranuclearophthalmoplegia, mild right ptosis, and slightposition sense loss in the right hand. The lesionwas clinically localized in the medial pons. Thepupils were of normal size and equal. This casewas believed to be similar to group 2a in whichthe responsible insult probably involved thedescending pyramidal fibres in the brain-stem.

4. HORNER'S SYNDROME (six cases) Six patientswith a Horner's syndrome had brain-stemlesions. Two of these patients had typical lateralmedullary infarctions and three had pontineinfarctions. In one case of pontine infarctionwith bilateral miotic pupils, there was bilateralptosis greater on the hemiparetic side (as in 2aand 3b). The remaining patient with a Horner'ssyndrome had an unusual clinical picture withsudden onset of rostral brain-stem and parieto-occipital infarction. The Horner's syndrome inthis case was probably related to diencephalicinfarction.

DISCUSSION

In this series, 11 patients had ptosis attributableto either a Horner's syndrome or third nervepalsy. In the 15 remaining cases of hemiparesis,ptosis was unilateral on the hemiparetic side inseven, bilateral but greater on the hemipareticside in four, and greater on the non-hemipareticside in four other cases. These findings suggestthat some control of elevation of eyelids isexerted cortically, probably bilaterally from onehemisphere, so that a hemisphere lesion causesbilateral ptosis. The symmetry of the ptosis maybe modified by widening of the palpebral fissuredue to facial weakness; or by an accentuation ofptosis on the hemiparetic side due to a disturb-ance of pyramidal fibres.

Evidence for cerebral control of the eyelidscomes from several neurophysiological studies.

Experiments by Ferrier (1875), Sherrington andGriinbaum (1902), and Leyton and Sherrington(1917) showed that, in the monkey, stimulatingan area anterior to the motor strip in the secondand third frontal convolutions consistently pro-duced bilateral eye opening, usually with turningof the eyes, head, and neck. Occipital stimulationin the monkey produced eye opening oftenaccompanied by conjugate turning of the eyes(Leyton and Sherrington, 1917; Walker andWeaver, 1940). Penfield and Rasmussen (1968)evoked eye opening by stimulating in awakehumans the prefrontal, occipital, and, rarely, theprecentral cortex.

Jackson hypothesized that bilateral lid move-ments, like thoracic and abdominal motions,were probably represented in each hemisphere.Gay et al. (1967) and Walsh and Hoyt (1969) citeextensive evidence that the eyelids work syn-kinetically. In the present series, five of thecerebral cases had bilateral ptosis, and twoothers possibly had the bilaterality of theirptosis obscured by a unilaterally widenedpalpebral fissure. Bilaterality of the ptosis mightwell be anticipated according to the experimentscited in which unilateral stimulation producedbilateral eye opening. It is a common experiencethat one cannot open one eye while keeping theother completely still. Although faulty eyeopening is a possible explanation of the bilateralptosis, in this series of cases asking the patient toopen his eyes fully produced nearly completeelevation of the upper lids. Another possibleexplanation for the ptosis is weakness or a de-crease in tone of the frontalis muscle, known toreceive bilateral innervation.

Blepharospasm sometimes occurs in patientswith hemiparesis (Fisher, 1963) and is a possiblemechanism for lid ptosis. In fact, four of thecases in this series with bilateral ptosis exhibitedforced lid closure when the lids were touched.Hysterical ptosis, another form of cerebralptosis, which was described in many 19th andearly 20th century textbooks of neurology andophthalmology is probably related to quasi-volitional lid spasm. Gowers (1893) emphasizedthat hysterical ptosis is generally accompaniedby a spasm in the orbicularis oculi, the latterusually readily proven by asking the patient tolook upward making the spasm of the orbicularisgreater in order to prevent the lid from moving

4

Protected by copyright.

on February 25, 2020 by guest.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.1.1 on 1 January 1974. Dow

nloaded from

Ptosis

upward with the eyeball. The phenomenon ofhysterical ptosis would be an example ofblepharospasm producing lids ptosed at rest.The finding of a widened palpebral fissure

associated with a central facial palsy is in agree-ment with the work of Penfield and Rasmussen(1968) who found that lid closure was the com-monest eyelid movement evoked by electricalstimulation of precentral cortex in man. Smith(1949) identified an area in the precentral cortexof monkeys just posterior to the arcuate sulcus,as a region from which eye closure could berepeatedly evoked by electrical stimulation.Since electrical stimulation of pyramidal tractregions leads to eye closure, a widened palpebralfissure could be readily interpreted as weaknessof eye closure. Though textbooks usually speakof lower facial weakness in upper motor neuronefacial paresis, Dejerine (1914) emphasized thatthe superior part of the face is always affected.In this series, four of the cerebral cases withptosis had a wide palpebral fissure on the hemi-paretic side.

Eleven cases had ptosis solely or accentuatedon the hemiparetic side. This observation gainsphysiological support from the observation thatLeyton and Sherrington (1917) were ableoccasionally to evoke eye opening by stimulatingportions of the precentral cortex in monkeys, andPenfield and Rasmussen (1968) were able toevoke eye opening by stimulating human pre-central cortex. Ptosis could be explained byfaulty unilateral eye opening on the side corre-sponding to the pyramidal tract deficit. How-ever, in each of these studies eye closure wasmore commonly evoked from stimulation ofprecentral cortex than eye opening. (Role (1968)has emphasized decreased lid tone as the sign ofupper motor neurone facial paresis in the stu-porous patient. A decrease in tone of theorbicularis oculi muscle may play a role in theptosis associated with pyramidal tract lesions.As already mentioned, in most cases of cere-

bral ptosis in the literature, pressure effects onthe third nerve or brain-stem were incriminated,although in the present series of vascular casesthis mechanism would appear to be excluded.Best (1931) described bilateral symmetricalptosis from a frontal lesion. Munk (1890) andvon Monakow (1914) reported ptosis from lesionsin the angular gyrus. Goldflam (1926) in dis-

cussing temporal lobe abscess noted that ptosiswas present in some cases. He felt that ptosis,like pain in the first division of the trigeminalnerve, was produced by pressure on the sympa-thetic or cranial nerves in the middle cranialfossa. Wilbrand and Sanger (1900) in reporting25 cases of cerebral ptosis pointed out the diffi-culty in attributing the lid sign to the cerebrallesion, since most patients had large tumourswith possible pressure effects. Krishna (1965) ina review of 60 cases of ptosis included 12 'cere-bral' cases (seven gliomas, four meningiomas,and two cases of subdural haematoma) ascribingthe ptosis in tumour cases to third nervepressure. Walsh and Hoyt (1969) added a case ofcerebral ptosis contralateral to a temporal lobeepileptic focus. Fisher (1967) described a case ofsubdural haematoma with ipsilateral ptosiswithout pupillary change. He tentatively attri-buted the ptosis to mechanical effects on ele-ments of the third nerve. Marquez (1936) in areview of abnormalities of the palpebral fissuredeclared that ptosis could occur as part of asupranuclear paralysis of third nerve functionproduced by lesions in the cerebral cortex orinternal capsule.Thus it is likely that there are hemispheral

sites both frontally and more posteriorly, de-struction of which produces bilateral ptosis. Thepresent cases do not identify the regions re-sponsible, since infarction in the territories ofthe middle and anterior cerebral arteries as wellas temporoparietal haemorrhage all producedbilateral ptosis. Facial paresis was not a neces-sary concomitant as it was absent in one case.This suggests that precentral and pyramidaltract pathways subserving supranuclear controlof the facial muscles need not be damaged incases of cerebral ptosis. At the same time, how-ever, pyramidal tract damage may modify thesymmetry of ptosis produced by lesions else-where, accentuating ptosis on the hemipareticside in some cases, and in others by widening thepalpebral fissure on the side contralateral to thelesion giving the patient the appearance of ipsi-lateral ptosis.Our observations on the duration of ptosis in

cerebral cases are fragmentary. In one case itlasted for two weeks and cleared while thehemiplegia persisted. In four other cases theptosis cleared as the remainder of the deficit dis-

5

Protected by copyright.

on February 25, 2020 by guest.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.1.1 on 1 January 1974. Dow

nloaded from

Louis R. Caplan

appeared. In two cases the ptosis still persistedwhen the patients were last seen a month afterthe onset of the stroke.The occurrence of bilateral complete ptosis as

the result of a presumably unilateral centralthird nerve lesion is of great interest. Theexplanation may be found in the work ofWarwick (1953, 1964) who, in an anatomicalstudy of the oculomotor nucleus in the monkeyidentified a caudal midline nucleus which con-tained a pool of motor neurones for the levatorsof the eyelids. The levators were the only oculo-motor muscles in which he could identify inti-mate bilateral central connections. This mightexplain the synkinesis of levator function alreadyreferred to above. Both cases in this series ofisolated levator paralysis in one eye had acomplete third nerve paralysis of the contra-lateral eye. The corollary might be proposed thatbilateral ptosis distinguishes a third nerve lesionnear or at its nucleus from a peripheral thirdnerve palsy. The complete inability to open aclosed eye might indicate the third nerve or itscentral neurones as the site of the lesion ratherthan a cerebral or pontine location.

Ptosis associated with a Horner's syndrome iswell known. Groch et al. (1960) reported fiveinstances of Horner's syndrome in patients withcarotid artery occlusion, the sympathetic paraly-sis being related to involvement of the nervesalong the carotid artery. O'Doherty and Green(1958) described a partial Horner's syndrome in12 of 18 cases of carotid artery occlusionemphasizing that the sign may be mild andtransient but offers an important clue as to thelocation of the thrombosis. In this series therewere two cases of Horner's syndrome related tocarotid artery occlusion and six cases with thesyndrome related to brain-stem interruption ofsympathetic pathways.

This preliminary study has shown that ptosisoccurs in hemispheral vascular lesions in theabsence of third nerve or sympathetic paralysis.Further observations are needed to identify thepathological anatomy and physiology of thecerebral ptosis. Recognition of cerebral ptosisand ptosis associated with pyramidal tract lesionsshould help to clarify heretofore puzzling cases inboth vascular and non-vascular disorders.

I wish to acknowledge the help of Dr. C. M. Fisher

whose advice and review of the manuscript havebeen of great value.

REFERENCES

Best, F. (1931). Die Augenveriinderungen bei den organischennichtentziundlichen Erkrankungen des Zentralnerven-systems. In Kurzes Handbuch der Ophthalmologie, Vol. 6,pp. 531-532. Edited by F. Schieck and H. Briuckner.Springer: Berlin.

Cogan, D. G. (1956). Neurology of the Ocular Muscles, 2ndedn, pp. 139-148. Charles C. Thomas: Springfield, 111.

Cole, M. (1968). Eyelid tone: a sign of facial paresis.Neurology (Minneap.), 18, 413-414.

Dejerine, J. (1914). Semiologie des Affections du SystinmeNerveux, p. 170. Masson: Paris.

Ferrier, D. (1875). Experiments on the brain of monkeys.Proceedings of the Royal Society ofLondon, 23, 409-432.

Fisher, C. M. (1963). Reflex blepharospasm. Neutrology(Minneap.), 13, 77-78.

Fisher, C. M. (1967). Some neuro-ophthalmological observa-tions. Journal of Neutrology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry,30, 383-392.

Fisher, C. M., and Curry, H. B. (1965). Pure motor hemi-plegia of vascular origin. Archives of Neurology, 13, 30-44.

Gay, A. J., Salmon, M. L., and Windsor, C. E. (1967).Hering's law, the levators, and their relationship in diseasestates. Archives of Ophthalmology, 77, 157-160.

Goldflam, S. (1926). Beitrag zur Symptomatologie desSchlafenlappenabszesses. Deutsche Zeitschrift fuir Nerven-heilkunde, 90, 38-100.

Gowers, W. R. (1893). A Manual of the Diseases of theNervous System, Vol. 2, p. 201. 2nd edn. Churchill:London.

Groch, S. N., Hurwitz, L. J., Wright, 1. S., and McDowell, F.(1960). Bedside diagnosis of carotid-artery occlusivedisease. New England Journal of Medicine, 262, 705-707.

Krishna, A. G. (1965). Ptosis. A clinical analysis of 60 cases.Journal of the Indian Medical Association, 45, 326-328.

Leyton, A. S. F., and Sherrington, C. S. (1917). Observationson the excitable cortex of the chimpanzee, orang-utan, andgorilla. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology, 11,135-222.

Marquez, M. (1936). La hendidura palpebral normal ypatol6gica. Medicina Ibera, Madrid, 1, 209-222.

Monakow, C. von (1914). Die Lokalisation im Grosshirn undder Abbau der Fuinktion durch kortikale Herde, p. 1033.J. F. Bergmann: Wiesbaden.

Munk, H. (1890). (Jber die Functionen der Grosshirnrinde.Gesammelte Mittheilungen mit Anmerkungen, pp. 9-316.Hirschwald: Berlin.

O'Doherty, D. S., and Green, J. B. (1958). Diagnostic valueof Horner's syndrome in thrombosis of the carotid artery.Neurology (Minneap.), 8, 842-845.

Penfield, W., and Rasmussen, T. (1968). The Cerebral Cortexof Man, pp. 51-52, 67-76. Hafner: New York.

Segarra, J. M. (1970). Cerebral vascular disease and behavior.1. Archives of Neurology, 22, 408-418.

Sherrington, C. S., and Griinbaum, A. S. (1902). A discussionon the motor cortex as exemplified in the anthropoid apes.British Medical Journal, 2, 784.

Smith, W. K. (1949). The frontal eye fields. In The PrecentralMotor Cortex, pp. 309-342. Edited by P. C. Bucy. Uni-versity of Illinois Press: Urbana.

Walker, A. E., and Weaver, T. A., Jr. (1940). Ocular move-ments from the occipital lobe in the monkey. Jouirnal ofNeutrophysiology, 3, 353-357.

6

Protected by copyright.

on February 25, 2020 by guest.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.1.1 on 1 January 1974. Dow

nloaded from

Ptosis 7

Walsh, F. B., and Hoyt, W. F. (1969). Clinical Neuro- Warwick, R. (1964). Oculomotor organization. In Theophthalmology, vol. 1, pp. 297-304. 3rd edn. Williams and Ocldomotor System, pp. 173-202. Edited by M. B. Bender.Wilkins: Baltimore. Hoeber: New York.

Warwick, R. (1953). Representation of the extra-ocular Wilbrand, H., and Sanger, A. (1900). Die Neurologie desmuscles in the oculomotor nuclei of the monkey. Joutrnal of Aiuges. 1. Die Beziehungen des Nervensystems -i denComnparative Neutrology, 98, 449-503. Lidern, Vol. 1, pp. 96-114. Bergmann: Wiesbaden.

Protected by copyright.

on February 25, 2020 by guest.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.1.1 on 1 January 1974. Dow

nloaded from

![ptosis [emedicine]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/577cdd4a1a28ab9e78acb3ee/ptosis-emedicine.jpg)