pT! - DISABLED VETERANS.ORG

Transcript of pT! - DISABLED VETERANS.ORG

IB

, GABE pT! ~, ~.!a

17JJ0

REPORTTO THE

NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL

D/8-go4'-p/Sa-

pl )3

US POLICY ON CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICALWARFARE AND AGENTS

Submitted by theInterdepartmental Political-Military Group

in response to NSSM 59

1ÃASE' '

IHI(a575'gl»—IIW~ T(Xt "* =

GRO UP 3Downgraded at 12 year intervals,not automatically declassified.

NOVEMBER 10,

I"

~I'MF

US POLICIES ON CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE AND AGENTS

Introduction

In response to NSSM 59, this report by the Inter-departmental Political-Military Group (IPMG) examines USpolicies, programs, operational concepts and alternativesthereto with regard to both chemical and biological war-fare+ and agents. Part I contains background informationon US policies and programs essential to an understandingof. the policy issues. Part II addresses the importantpolicy issues and options, and the relevant pros and cors .

While chemical and biological weapons are oftenreferred to as a single group or category, there areimportant distinctions between them. For purposes ofpolicy, international law, military application andpublic discussion, it is essential that these distinc-tions be kept clearly in mind. For the purposes of thisreport, CW and BW are considered separately. There arealso significant differentiations within the broadchemical and biological categories that require separateconsideration.

Biolo ical a ents require a period of incubationbefore they can take effect, and are generally notconsidered useful where rapid results may be requiredin tactical or battlefield situations. There are twoother notable characteristics of biological weapons:

First, a small amount of an agent (in terms ofweight, and bulk) has the potential to infect a larg&target area measured in hundreds of square miles.

Department of Defense prefers the terms "biologicalagents" or "biological research agents. "

Second, it is difficult to confine their effects toa given target area. With some agents, the disease couldspread beyond those originally infected with it.

Various living organisms (e.g. , rickettsiae, virusesand fungi), as well as bacteria, can be used as weaponsand, in the context of warfare, are generally recognizedas biological warfare agents.

Most chemical a ents take effect rapidly. Consequentltthey are more suitable for battlefield situations. Howeverconsiderably larger quantities of chemical agents must bede 1ive re d on t a rge t to p rod uce de s ire d e ffect s.

For purposes of this report chemical and biologicalagents are categorized as follows:

Lethal A ents - Chemical and biological, are thosewhich are intended to cause death. (We have includedmustard gas in this category. )

Inca acitatin A ents --Chemical and biological, arethose which are intended to cause temporary disabilitywithout residual injurious e ffeet.

Riot Control A ents - A few chemical agents such astear gases, have been used by governments in civil disturbances, and in warfare for a variety of other missions.These latter are referred to in this report as riot contro~sents (RCA) .

Chemical herbicides are used as defoliants and ast - P B t . B 1 1 t - ~t t t

for use only n'gainst crops.

Smok1 liame nnd incendiar a cnts arc not cat&:;;orixias either CW or BW and are not dealt with in this report.

~589I~3-

As far as is known, biological agents of warfare havenever been employed in modern times. On the other hand,lethal chemical agents have been employed: (1) by bothsides during WW I; (2) by Italy during the Abyssinianconflict (1935-6); (3) by Japan in China in 1939-1942; and,(4) by the UAR against Yemeni royalists in 1962-1967.

Riot control agents (tear gas) and herbicides havebeen used by the US and its allies in Vietnam. Smallquantities of tear gas have been used by the other side.

Part I: Back round

A. Statement of the Problem

Since World War I the US has maintained a chemicalwarfare (CW) program, and since World War II a biologicalwarfare (BW) program. Yet during these years the UnitedStates has not had a fully developed national policy ineither the CW or BW fields.

Recent developments have generated considerable con-troversy over US policies and programs. These include:

l. A series of incidents relating to testing, trans-portation, disposal and overseas storage.

2. The use of riot control agents and chemicalherbicides in combat situations by US forces in Vietnam.

3. The introduction of new arms control initiativesin the international arena, both at the CCD at Genevaand the UNGA, and in the Secretary General's report.

4. Congressional reviews and proposed restrictions.

B. The Nature of the Threat to the US and Its Allies

1. Soviet Chemical Warfare

Information about the USSR's CW program is ratherextensive yet incomplete in some important details. Onesuch detail concerns the size of the Soviet toxic agentsstockpile.

5

,this stockpile zslarge* and militarily significant.

The Soviets class CW weapons with nuclearweapons as "weapons of mass destruction. " We concludethat the use of chemical weapons by the USSR is subjectto the same type of political control at the highestlevel as are atomic weapons. We believe it virtuallycertain that they would use-CW- in the event of generalnuclear war if they considered it to their advantage todo so. We believe, however, that they would not initiatetheir use in a conventional conflict against an opponentcapable of retaliation in kind. They would not hesitateto retaliate with CW if chemical weapons were used againstthem in a conventional war.

Soviet documents indicate that the USSR expectsNATO to employ BW as well as CW in the event of war andis preparing against both. It is worth noting that theSoviets have maintained an active defense program overthe years in an attempt to reduce the vulnerability oftheir population to chemical, biological, and radiologicaleffects.

The Soviets appear to appreciate both the capa-bilities and limitations of chemical weapons. Soviet doctrinetactical use of chemical weapons appears to be based onthe concept of utilizing the best attributes of theseweapons in relation to HE and nuclear weapons. Thus,

* The Department of State view is that given the paucityof available evidence, as is reflected in the above,it is not possible to characterize the size of thestockpile. DIA believes it is possible to characterizethe size of the stockpile.

- 5

;this stockpile islarge* and militarily significant.

The Soviets class CW weapons with nuclearweapons as "weapons of mass destruction. " We conc ludethat the use of chemical weapons by the USSR is subjectto the same type of politica'1 control at the highestlevel as are atomic weapons. We believe it virtuallycertain that they would use CW in the event of generalnuclear war if they considered it to their advantage todo so. We believe, however, that they would not initiatetheir use in a conventional conflict against an opponentcapable of retaliation in kind. They would not hesitateto retaliate with CW if chemical weapons were used againstthem in a conventional war.

Soviet documents indicate that the USSR expectsNATO to employ BW as well as CW in the event of war andis preparing against both. It is worth noting that theSoviets have maintained an active defense program overthe years in an attempt to reduce the vulnerability oftheir population to chemical, biological, and radiologicaleffects.

The Soviets appear to appreciate both the capa-bilities and limitations of chemical weapons. Soviet doctrnm ontactical use of chemical weapons appears to be based onthe concept of utilizing the best attributes of theseweapons in relation to HE andmuclear weapons. Thus,

* The Department of State view is that given the paucityof available evidence, as is reflected in the above,it is not possible to cha'rac'terize the size of thestockpile. DIA believes it is possible to characterizethe size of the stockpile.

-6-

chemical weapons may be used instead of nuclear weaponswhere physical destruction of a target is not desirable.In small sectors, large-scale use of chemical warfaremight be used to produce large casualties as well as todemoralize enemy troops and to facilitate movement ofground forces. Fram the Soviet point of view, chemicalweapons are especially advantageous for use in mountainousterrain, where precision artillery or aircraft bombard-ment is difficult, and in other areas where natural orconstructed physical features protect. personnel from theeffects of nuclear and/or high explosive detonations.We have good indications that current Soviet plans forgeneral nuclear war call for about one-third of allwarheads available for Soviet ground-launched tacticalmissiles and rockets to be chemical.

There is better information regarding researchand development that may relate to CW and on doctrine fortactical use than on the production of chemical agents.It is known that the Soviet Union has considerable interestin CW and that the Soviet arsenal iricJ.udes CW agents ofthe WW-I type as well as the more recently developed nerveagents. Soman, which appears to W a major component ofthe Soviet nerve agent stockpile, is 'of special concernto the West because it is resistant to the usual nerveagent antidotes and therapy. Another important Sovietnerve agent, appears to be aV-agent type material. Its toxicity fs believed toexceed somewhat that of UX standardized by the West. A

point of particular relevance to this study is that theSoviets appear to be emphasizing letha 1 agents in theirCW activities and, while we have evidence of their R&D

interest in them, there is no evidence that they arestockpiling incapacitating agents of any type.

The USSR possesses considerable productioncapacity and storage facilities which would be suitablefor lethe L agents.

Just how ready Soviet forces are for offensiveCW and how far forward stocks of chemical munitions aremaintained are matters on which there is still uncertainty&but there is good reason to believe that weapons capableof delivering chemical munitions are available at division,army, and "Front" level. There are increasing indicationsthat at least some quantities of CW agents are storedunder Soviet control in non-Soviet Warsaw Pact (NSWP)countries. We believe that the Bloc countries are notproducing CW agents nor are they allowed ro accumulatestocks of them free of Soviet control. The Warsaw Pact'scurrent capability to wage CW in Europe undoubtedlysurpasses that of NATO.

Defensive CW equipment includes protection,detection, and decontamination equipment effective againstall known lethal chemical agents; Soviet Bloc attention to.defensive CW training and protection against chemicalattack exceeds that of the US as well as of its NATO

allies. Most new construction Soviet ships are providedin varying degrees with washdown systems, filtered ventila-tion systems and decontamination stations that would enablethe ships to,carry out their assigned missions in a CBenvironment. Extensive training is provided for themaintenance of a permanent, high level of CW and BW readi-ness for the various naval units.

- 8

2. Soviet Biolo ical Warfare

Our intelligence on Soviet BW capabilities ismuch less firm than on CW activities. Soviet interestin various potential biological uarfare agents has beendocumented and the intelligence community agrees thatthe Soviets have all the necessary means for developingan offensive capability in this field. '

In Soviet writings, BW is linked with nuclearand chemical warfare in terms that indicate a highdegree of political control and restraint. We believethat Soviet vulnerabilities would weigh heavily againstcnemis at ini tia tion of BW.

There are frequent Soviet references to BW

weapons as a "means of mass destruction" that would beused in future conflicts. We believe it unlikely thatthe Soviets would employ BW as a primary means of initialstrategic attack, although it might subsequently be usedin the course of a gener'al war. Soviet and NSWP militaryforces, including naval unit~ are equipped with personneland collective protective devices which could enable themto operate in a biological warfare environment. The Sovietsprobably believe that biological warfare weapons can bee ffee tive in some tact ica I situations, though ine ffectivein many, and are especially suitable for clandestinedelivery.

3. CBW Ca abilities of Other Countries

There is evidence of Chinese Communist interestin the CBW weapons field, but Communist China at presenthas at most an extremely limited offensive capability inchemical agents only.

A limited chemical and biological warfare capa-bility, at least in terms of crude weapons, can be acquiredby States with even a limited modern industrial base.Important aspects of CBW technology are widely known andeasily obtainable through open sources. Some existingchemical and pharmaceutical facilities can be adapted forthe development and production of CBW agents. As deliverycan be accomplished by several kinds of relativelyunsophisticated weapons, the acquisition of a limitedoffensive capability in BW and CW need not be expensive.

It should be noted that there is evidence ofinterest on the part of some nations

in acquiring or enhancing CBW capabilities and oflimited use of chemical weapons by the UAR in Yemen.Considerable related and high-quality research is evencarried on by countries that indicate no intention ofdeveloping offensive capabilities of their own (e.g. ,Sweden).

C. Current US Polic

There is no document that sets forth National Policyin this field comprehensivelymr definitively. Discernibleelements of a National Policy have been suggested in state-ments by US officials, and in Government documents.Nowever, the extent to which these define policy is unclear.The lack of clarity concerns what the US policy is, wherethat policy is to be found, the reach of that policy, andwhether that policy purports to-be based upon rules ofinternational law.

The only public statement of policy by a Presidentwas Roosevelt's 1943 statement which emphasized twopoints: (a) no first-use of poisonous or noxious gasesand (b) "retaliation in kind. " The terms "poisonous ornoxious gases" have never been officiall'y defined by a USspokesman.

Presidential policy guidance was incorporated in theBasic National Security Eblicy (BNSP), which was issued onAugust 5, 1959 and rescinded in January 1963. It stated:"The United States will be prepared to use chemical andbiological weapons to the extent that such use willenhance the military effectiveness of the armed forces.The decision as to their use will be made by the Presi-dent. If time permits and an attack on the United Statesor US forces is not involved, the United States shouldcons'ult appropriate allies before any decision to usenuclear, chemical and biological weapons is made by thePresident. "

On November 17, 1966, in a letter to the Secretaryof State, the Secretary of Defense proposed DOD respon-sibilities for CW and BM in the following terms;

"It is in the national interests of theUnited States to be prepared to employ CB weaponsand to maintain a balanced offensive and defensivecapability for CB operations. The possession ofa credible capability to employ them could detertheir use by an enemy. Accordingly, US forcesshall be prepared to defend against CW weaponsby an enemy, to conduct operations in a toxicenvironment, and to use these weapons when directedto do so. The President does not now expect toauthorize US forces to use lethal anti-personnelCB weapons prior to- their use by another nation.In certain situations of national urgency, thePresident may authorize the use of CB incapaci-tating weapons. "

11

Ther» is no extant p'olicy directive from a Presidentthat requires Presidential authority prior to employmento f these weapons. However, DOD policy spec if i»s that thePresident must approve the employment of CW and BW otherthan riot control agents and herbicides. President Johnsonreaffirmed the authority of the JCS to authorize use ofRCA's in Vietnam.

D. US Chemical Ca abilities Stock ile R&D and Costs

1. Current Lethal Chemical Ca abilities

A review of the current US chemical postureindicates the following: The US inventory of chemical~gents, mustard and nerve agents GB and VX, is approxi-mately 30,000 tons. Of this amount, 13,000 tons areWW I mustard agent. The immediately usable portion ofthe US stockpile amounts to about 18,400 agent tonsconsisting of the agents in filled munitions plus bulkstocks for munitions to be filled in the field.

Stocks in Europe would provide about 97 tons ofground munitions each for the five US divisions nowcommitted to NATO or about five tons of ground munitionsper US and NATO division if chemical operations beginafter D+60, versus estimated requirements of about 8 tonsper day. Stocks now in the Pacific (currently on Okinawabut to be removed) total about 1,600 tons for the entiretheater. Total US inventories of 155 mm and 8-inch GB andVX munitions and 'aircraft spray tanks are grossly inadequateto engage in large-scale chemical operations in either Europeor the Pacific.

2. Inca acitatin Chemical A ent Ca abilities

The one standard chemical incapacitating agent,BZ (stockpile 49 tons) is unlikely to be employed due toits wide range of variability of effects, long onset time,and inefficiency of existing munitions. Agents in R&D, which mayhave greater military potential', are not currentlystandardized.

12

3. Riot Control A ent RCA Ca abilitiesRCA's are being procured commercially to support

both Southeast Asia operations and civil disturbancemissions. Stockpiles are located in CONUS and overseas.

4. Herbicide Ca abilities

Defoliants have been and are used on a con-siderable scale in Vietnam, and have proven effectivein clearing the sides of roads, canals and rivers andaround encampments. The US has also conducted chemicalanti-crop missions in Vietnam and Laos.

5. Chemical Defense Ca abilities

Over-all, the present US chemical defensiveposture is marginal or poor, allied defensive capabilitiesare even worse. US chemical defensive posture providesprotective masks, some manual detection and combat vehiclecollective protection. There are no plans or capabilitiesfor protection of the US civilian population. However,a mask for the use of the civilian population has beendeveloped and tested.

6. Chemical production Ca abilities

Decisions on new or future procurement of lethalchemical warfare agents and related delivery systemsare deferred pending the outcome of this NSSM. Nooperational chemical warfare agents are being produced.No delivery systems are being procured. No additionalagent production is programmed until binary agents becomeavailable.

The United States has no production facilitiesfor bulk mustard. Riot control agents, herbicides, andthe chemical incapacitant BZ are procured commercially.

13-

Production facilities for the nerve agents GB and VX arein lay-away status. Under emergency conditions, GB pro-duction could be resumed in 12 months, with maximumproduction by 15 months, and VX-in nine months, withmaximum by 12 months. Neither on-hand stocks in CONUS,nor pre-positioned stocks overseas, nor the sum of these,is capable of sustaining large-scale chemical operationsuntil production could be resumed.

7. Bins Munitions

The US is developing a shell or bomb in whichtwo non-toxic chemicals are filled in separate compart-ments. The chemicals are mixed after firing and form alethal chemical agent, which is disseminated when themunition arrives on target. The development of suchweapons is expected by 1974 at the earliest.

Binary munitions are safer during storage andhandling than previous chemical munitions and may alleviatemany problems - both technical ard political - that presentagents raise. During storage and transportation, the twocomponents could be separated so that if an accidentoccurred there would be no formulation, much less release,of toxic materials. Binaries could be dispersed as areconventional munitions instead of having to be stored inspecial ammunition storage sites.

For binaries, there would probably be no needto construct and operate large, costly government-ownedtoxic production facilities. The components, beingrelatively non-toxic, could easily be manufactured bythe US chemical industry and procured by DOD on competi-tive contract purchase.

~lgIRa&14-

8. Current Costs of Chemical Pro rams

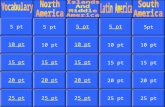

The proposed FY 70 funding for chemical warfareis shown below:

Procurement

Lethal ChemicalsIncapacitating ChemicalsRiot Control Agents & WeaponsHerbicidesDefensive Equipment & Misc.

($ in millions)

00

571028

Sub Total 95

RDT&E ($ in millions)

General InvestigationsOffensive R&DDefensive R&DTest & Evaluation

8201911

Sub Tots'1 58

~Ot IMaintenance of Depots,

Transportation 15

Military Construction

Sub Total 19

Total 172

* The report of the House-Seriate conference on 4 November1969 indicated a reduction of $10.5 million in RDT&E onchemical and biological warfare agents and delivery systems,a reduction of about 11 percent from the President's budgetfigures shown in thiq +)I gandm~table on page 16.

- 15

E. US Biolo ical Ca abilities Stock ile R&D and Costs

1. Current 0 erational Ca abilities

No large inventory of dry (powdered) anti-personnel lethal or incapacitating biological agents ismaintained and only eight aircraft spray disseminatorsare in the inventory.

No missile delivery capabilities are currentlymaintained for delivery of biological agents, although abomblet-containing warhead for the SERGEANT missile hasbeen standardized, but not produced in quantity.

Small quantities of both lethal and incapacitat-ing biological agents are maintained in special warfaredevices.

2. Current Research and Develo ment Pro ram

Funds — RDT&E funds for the biologicalresearch program reached a-. high. .point of $39 millionin FY 64 and since have been reduced by DOD action to$30 million.

- 16-

b. Defensive Problems - Timely detection ofan attack and the identification of the agent used arethe major defensive problems. Ne biological detectionsystem is presently deployed or in prospect. There isno effective prophylaxis for large-scale or multi-agentbiological attacks. No nation is known to have solvedthese problems.

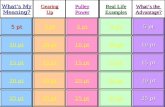

3. Costs of Biolo ical Pro rams

The total biological program has a relativelylow dollar cost as the table below indicates. Replenish-ment of the current existing biological stockpiles hasbeen stopped since August 1969, pending a decision of thisNSSM.

(Annual Cost of CurrentBiological Program inMillions of Dollars)

Total RDT&E*(including basic cost) $29.4

Replenishing existingStockpiles 1.5

Operation and Maintenance ofexisting Pilot Plant Pro-duction Facility 5. 5

TOTAL $36.4

F. Milita Considerations and Doctrine

Doctrine, as well as US military policy, governingthe use of CW and BW weapons, may be found in the plansdeveloped by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in studies pre-pared for them on concepts of 'operational use, and in thevarious service field manuals that provide direction onCW and BW employment and defense.

See footnote on gfg@kl$1qg j]

, CKADR

17

US military doctrine views CW weapons as having awide variety of possible military uses both in defensiveand in offensive (retaliation as well as first use)warfare throughout the entire spectrum of conflict rang-ing from counterinsurgency operations to general war.

Defense. Given adequate warning devices and propertroop training, equipment such as gas masks, protectiveclothing, airproof structures with filtered ventilation,and decontamination equipment, a reasonably successfuldefense against either lethal or non-lethal chemicalagents can be made. The requirement of preparing forchemical operations impose certain disadvantages, princi-pally by restricting maneuverability through logisticallyencumbering defensive equipment. Battlefield defensesagainst chemicals would be largely effective againstbiological agents.

Delive S stems. The various chemical and biologicalagents can be delivered by a wide variety of weapons.Artillery shells with chemical-agent projectiles have alimited-area coverage capability. This can be enlargedby rockets whose warheads, if massed, can attack targetson the order of several square kilometers. For evenlarger attack areas, rockets and missiles with self-dispersing bomblets can be used. Conventional minefieldscan be reinforced by mines containing persistent chemicalnerve agents.

Chemical agents can also be delivered by aircraft bymeans of bombs, spray tanks, cluster-bombs and dispensersof self-dispersing bomblets. Dissemination by helicopter'in a variety of situations is also feasible. The majordelivery means for biological agents in the presentmilita ry inventory is a ircra ft spray tanks.

C'

r

- 18-

All of these weapons are to some degree sensitiveto variations in the environment in which they are to be

/used. In some cases, there is considerable uncertaintyas to the effects of different terrain and weather condi-tions on particular agents. The effects of chemical andbiological agents depend to varying degrees upon agentand proposed use and on specific conditions of wind,temperature, humidity, and terrain.

G. Arms Control Initiatives in the International Arena

At the July 10, 1969 session of the ENDC, the UnitedK~dp td d ff t, d p y1gdraft Security Council Resolution (ENDC/255), which wouldban research aimed at producing biological agents forhostile purposes, and production, possession and use inany circumstances of biological methods of warfare. * Thedraft treaty does not provide for on-site verification,but it does contain complaint procedures for investigationof treaty violations under UN auspices. No consensus hasemerged on the UK draft, but many delegations in Genevaopposed the attempt to give separate treatment to biologicalweapons. The US, in informal sessions of the ENDC and inmeetings with the British, commented on the UK drafts with-out in any way preempting decjsiofis likely to follow thecurrent NSSM exercise. As a result of these informal sessions,the UK submitted a revised draft convention on August 26, 1969.

Also in early July, the Re ort of the UN SecretaGeneral on CBM was distributed at Geneva and the UN, andwidely publicized. The Group of Consultant Experts, whoprepared the report, including a representative from theUS, cited the danger of proliferation of these weapons andconcluded that the momentum of the arms race would clea rlydecrease if their production were effectively banned.

* The UK stated at the July 2 NAC discussion of their con-vention that parties would be free to produce biologicalagents for use in vaccines, — etc. The convention does notattempt to establish exactly what level of production ortesting is consistent with a passive defense capability.

~ggg

, GAOL~i~LIL@killl IN

- 19-

The Secretary-General urged in a forward to the Reportthat UN Members undertake the following measures:

1. To renew the appea& to all States to accedeto the Geneva Protocol of 1925;

2. To make a clear affirmation that the pro-hibition contained in the Geneva Protocol appliesto the use in war of all chemical, bacteriologicaland biological agents (including tear gas and otherharassing agents), which now exist or which may bedeveloped in the futur'e;

3. 'To call upon all countries to reach agree-

ment to halt the development, production and stock-piling of all chemical and bacteriological (biological)agents for purposes of war and to achieve theireffective elimination from the arsenal of weapons.

Sweden, on August 26, 1969, introduced a UNGA draftresolution which condemns and declares as contrary tointernational law the use of any C and B agents in inter-national armed conflicts. The draft resolution statesthat an existing customary rule of international lawprohibits the use in international armed 'conflicts of allbiological and chemical methods of..warfare.

Canada, also has submitted a draft resolution tothe UN General Assemb'ly. It reiterates, inter alia, aprevious UNGA' invitation to all States to accede to the1925 Protocol, recommends that the UNSYG's report beused as a basis for the CCD's further consideration ofthe elimination of C and B weapons, and urges the CCDto complete work on the UK draft convention at an earlydate.

The USSR, as well as most members of the CCD, haveinsisted on: (1) the need for universal adherence to the1925 Geneva Protocol as a condition precedent to the con-sideration of more compfehensive measures; and (2) theundesirability of according separate treatment to C andB weapons.

- 20

At the UN General Assembly, on September 19, 1969,Foreign Minister Gromyko announced that the USSR, allother Warsaw Pact countries (except East Germany), andMongolia were submitting to the 24th UNGA an item onconclusion of a convention on the Piohibition of Develop-ment, Production and Stockpiling of Chemical and BiologicalWeapons and on their Destruction. The Soviet draft conven-tion would ban development, production, stockpiling ora'c'quisition of both chemical and biological weapons. Itrelies on self~olicing rather than on any plan of inter-national control by inspection. 'The Soviet initiative hasbeen allocated to Committee One of the UNGA for debatethis fall along with the Report of the CCD (CBW relatedsections) and the Secretary-General's Report on CBW.

H. Coo erative Pro ram with Allies

The United States has a cooperative research agree-ment with Great Britain, Canada and Australia for theexchange of chemical and biological warfare information.We have less extensive CBW information exchange agreementswith other countries, including Germany. Under the agree-ment with Germany, the US has provided over the years small,sample quantities of agents for use in RDT&E of defensiveequipment. The extent to which this practice will becontinued will be reviewed in the light of the decisionsmade by the NSC on the fundamental issues raised in this .study.

I. The USEof Tear Gas CS in South Vietnam

1. CS has been used in South Vietnam since 1965.CS provides the possibility of a nonlethal solution tomilitary operational problems and their military utilityin the folloiwng circumstances:

a. Increases the possibilities of the captureof PW's from mixed military/civilian population withoutcivilian casualties.

21-

b. In urban areas, decreases the destructionof housing and public facilities. Any destruction ofhousing or public facilities provides the VC with tangiblepropaganda and is used against Zhe United States.

c. Provides the commander with a nonlethaloption to the use of massive HE in overcoming a dug-inenemy. (CS forces enemy into the open where he has theoption of surrendering. The alternative to CS use ismassive use of HE, killing or trapping the enemy indestroyed fortifications, or exposing American soldiersby attacking individual fortifications by gun and bayonet.Friendly casualties in this method of attack are extremelyhigh, while use of CS allows great reduction in friendlycasualties and gives the enemy the option of surrenderingif he so desires. )

d. If used for area restriction, it limits theuse of terrain and prevents reuse of field fortifications.Denial of areas with CS has in many cases altered enemyinfiltration routes and thus required him to develop newroutes. It can also be used to canalize an enemy assaultand increase enemy vulnerability.

e. In reconnaissance-by-fire employing CSrather than HE shells, it is particularly effective forchecking heavily wooded areas and is much more effectivefor detection of occupied fortifications than is HE.

2. CS, when used in offensive operations,

a. Assists in the assault of point targetssuch as bunkers and automatic weapons emplacements.Within a few seconds any occupants lacking protectionagainst CS will be rendered unable to defend themselvese ffective ly.

- 22

b. Aids in the assault of area targets.

c. Is effective in flushing bunkers and caves.

d. Is very useful in the suppression of small-arms fire around helicopter LZ's.

3. CS when used in defensive operations:

a. Assists in perimeter defense by impedingapproaches to and passages through the perimeter.

4. CS has been found to be increasingly effectiveby military commanders in South Vietnam. Procurement ofbulk CS, primarily to support SVN, has amounted to3.5 million pounds in FY 1968 and 4.0 million pounds inFY 1969. Sixteen hundred tons have been expended in thepast 18 months.

J. Public Attitudes in the International Arena

Public attitudes toward chemical and biological weaponshave generally been largely formed by: (a) continuedCommunist propaganda charges citing US failure to ratifythe 1925 Geneva Protocol; (b) US use of riot control agentsin Vietnam since 1965; (c) The Communist campaign of theearly 1950's charging the US with germ warfare in Korea.A series of accidentis since early 1968, and the US domesticcontroversy over transport and storage of chemical agents,has sharpened public criticism here and overseas.

g~lgSIP23

Part II: CW and BW Folic Issues

Int rod uc t ion

Before the nature, scope and direction of a coherentUS policy for CW and BW can be decided upon, several under-lying issues should be addressed and resolved. These issuesfall into three categories.

The first two categories deal with CW and BW programsrespectively, for policy will indeed be concerned with theobjectives, scope and nature of future programs. The thirdcategory deals with a set of issues concerning the publicand international posture of the US on CW and BW issues.This involves legal issues, arms control policy, and US

positions in international conferences and negotiations.

Before examining the various policy issues, over whichthere is disagreement, a few areas of agreement deservemention.

First, there is need for a continuing US RDT&E programto improve defenses and guard against technological surprise.Indeed, there is a consensus that, regardless of decisionson the following issues, there should be more emphasis upondefensive measures and programs.

Second, the US should continue to work on, develop andimprove controls and safety measures in all chemical andbiological programs.

Third, a requirement exists for more definitive intelli-gence on other nations' CBW capabilities.

Fourth, Declaratory policy with respect to lethal chemicalsand lethal biological agents is ynd should continue to be"no first use. "

svIINIOim

-24-

Fifth, no agents except RCA's and/or herbicides canbe used except with Presidential approval.

Finally, to try to keep public opinion problemsmanageable, public affairs policy should be planned andimplemented on an inter-agency basis in close integrationwith substantive policy.

I. BW Polic Issues*

A. Should the US maintain a lethal biolo ical ca abilit ?

Pros:

1. Maintenance of such a capability could contri-bute to deterring the use of such agents by others.

2. Without any production capability and deliverymeans for lethal agents, the United States would not be ableto reconstitute such a capability within likely warningtimes.

3. Retains an option &r the United States atvery little additional cost as a hedge against possibletechnological surprise or as a strategic option.

Cons:

1. Control of the area of effect of known BW

agents is uncertain.

* Relevant legal arguments are discussed in Section III E .Although BW agents do require large safety zones, theircontrollability under other than a strategic attackis possible, based on results of testing to date.

25

2. A lethal BW capability does not appear necessaryto deter strategic use of lethal BW.

3. Limits our flexibility in supporting arms controlarrangements.

B. Should the US maintain a ca abilit for use ofinca acitatin biolo icals? (We now have two biologicalincapacitants in stock. )

Pros:

1. From a military standpoint, incapacitatingbiologicals might be an effective method of preparing foran amphibious invasion, disrupting rear-echelon militaryoperations, or of neutralizing pockets of enemy forces.

2. Biological incapacitants could provide in somecircumstances a method of capturing particular targets orareas which might be more humane than conventional weapons.

3. Without a production facility in being at thepresent -state of readiness, it would take approximately 2-3years, starting from scratch, to produce biological agentsin militarily significant quantities.

4. Maintains the only existing US incapacitantcapability for those situations where incapacitation overa period of several days is desirable.

Cons:

1. Biological incapacitants have a questionabledeterrent or retaliatory value.

2. First-use of incapacitating biologicals would beconstrued by most nations, including most US Allies, to becontrary to international law. and the Geneva Protocol.

- 26

3. An enemy may perceive no clear-cut distinc-tion between incapacitating and lethal agents under wartimeconditions.

C. Should the US maintain onl an RDT&E ro ram:

There are really two sub-issues here: (1) should theU. S. restrict its program to RDT&E for defensive purposes onlyor (2) should the U. S. conduct both offensive and defensiveRDT&E? While it is agreed that even RDT&E for defensivepurposes only would require some offensive R&D, it is alsoagreed that there is a distinction between the two issues.A defensive purposes only R&D program would emphasize basicand exploratory research on all aspects of BW, warning devices,medical treatment and prophylaxis. RDT&E for offensive pur-poses would emphasize work on mass production and weaponiza-tion and would include standardization of new weapons andagents. If a decision were made to continue an RDT&E programfor defensive purposes only, it would be necessary to reviewthe necessity for retaining existing production facilities.

(1) - in the offensive and defensive areas?

Pros:

1. Ninimizes risks of technological surprise.

2. Provides knowledge and capability for physicaland medical defensive measures.

3. Retains a relatively short lead time for responseto new threats (depending on level of RDT&E effort).

Cons:

1. Could hc construed as preparation to usc bio-logical agents in war.

2. Would degrade VS capability for response in kind.

3. Would reduce US response options.

- 27

(2) - in the defensive area onl ? (Maintenance ofa defensive RDT&E program inherently requires some offensiveRDT&D effort. )

Pros:

1. Would provide some knowledge, although lessthan with the preceding option.

2. Would result in a more economical program.

in war.3. Could not be construed as preparation for use

Cons:

1. Would, as compared with (1) above, furtherdegrade US capability to employ biological agents.

2. Could require disposal of certain material andfacilities and loss of expertise.

surprise.3. Would increase the hazard of technological

D. Should the US su ort the UK Draft Convention forthe Prohibition of Biolo ical Methods of Warfare? (For briefdiscussion, see page 18.)

Pros:

1. If the US decides not to maintain a lethalbiological capability, it would be in our interest to obtainan undertaking by others not to do so.

2. The UK Convention contains provisions forinvestigations of allegations of violations, and an escapeclause, both of which may provide some measure of securityto the parties to the agreement.

"

28

3. If the US limits its BW program to RDT&E,the security of the US would be no more endangered underthe UK agreement thatn it would 3&e in the absence of anagreement, and the inhibitory aspects of the conventioncould be important.

4. The British interpret their Convention topermit the development of a passive defensive capabilityagainst BW, e.g. , development of vaccines and the pro-duction of protective and warning devices.

Cons:

1. The Convention does not provide assuranceof compliance because there is no provision for on-siteverification and violations could not be detected by uni-lateral means alone. Acceptance of an unverifiabletreaty provision would weaken our ability to resistsimilar obligations in other arms control contexts.

2. Would require the US to renounce all exist-ing offensive biological capabilities and thus woulddeprive the US of options it might wish to exercise inthe future.

29

II. CW Polic Issues~

A. Should the US maintain a -ca abilit to retaliatewith lethal chemical a ents? There is no consensus onwhat constitutes ade uate reta liator ca abilit

Pros:

1. The principal argument in favor of the develop-ment. and stockpiling of lethal chemical agents is that such

capability is needed to deter possible use against US orallied forces by others in war.

2. Reliance on nuclear weapons as the sole deter-rent against CW would deny to the decision-maker the lethalchemical option in retaliation, in the event US or alliedforces were subject to a CW attack. Depending on the mili-tary capabilities of the enemy, an expanded conventionalresponse could be inadequate and a nuclear response couldprove too escalatory.

3. A response in kind would force an enemy tooperate under the same cumbersome operational constraints(protective clothing, movement limitation and limited logis-tics) which would be imposed on our forces.

4. If the US were unilaterally to eliminate itslethal CW capability, this would remove a major bargaininglover for obtaining sound and effective arms control measures .

Cons:

1. The principal argument against the developmentand stockpiling of a lethal chemical capability is thatother military means, including a whole range of nuclearweapons, are sufficient to deter the use of lethal chemicals.

2. The deterrent threat of retaliation with nuclearweapons against a CW attack 'could- be more credible if the US

were to eliminate its CW capability.

Relevant legal arguments are discussed in Section III E

Bh;

- 30-

B. Should the US destro or detoxif its stock iles ofmustard? All stocks of hos ene have been dis osed of.

Pros:

l. Mustard is an obsolete World War I type gaswhich has considerably less military utility than modernnerve agents.

2. An announcement that we planned to dispose ofthese stocks would help to demonstrate US interest in con-trolling lethal chemical munitions and thus might have somepolitical value.

Cons:

Would remove about 40% of existing lethalchemical artillery capability which although not as desirable«s nerve agents do have a proven casualty producing capability. '

For these reasons, destruction is not appropriate until binaryagents are available.

C. Should the US continue to maintain stock iles ofChemical munitions overseas 1 in Euro e and 2 in thePacific'? (Euro ean stock ile is onl in German

Pros:

1. Stockpiles in close proximity to where theymay be used are necessary for deterrence and for a timelyand adequate response. Current stocks in Europe representonly 6-10 days of combat usage mnd in Asia about 15 days.

2. Not to continue to maintain chemical munitionsoverseas would impose a delay of at least 14 days for initialrc s ponse and up to 75-90 days for sustained operations.

- 31

3, If stockpiles are not established during peace-time, it might be provocative to attempt to reinforce chemicalstocks quickly in a crisis.

Cons:

1, Present stocks do not provide a significantoperational capability; the expansion of overseas stocksnecessary to create such a capability could involve increasedpolitical problems for the US,

2. Even maintaining present stockpiles of lethalchemical agents on foreign territory could become a source ofpolitical fritction with the host country.

D. Should the US consult with the FRG concernin the USCM stock ile in German

Pro:

Early discussion would help to remove a possibleirritant ln relations before it developed into a major issue.

Con:

If t'he US decides to retain these stocks, raisingth» issue could unnecessarily jeopardize this objective andplace ih» FRG in an awkward position.

F. Should the US reserve a first -use o tion forinca acitatin ~ chemicals ?s

Pros:

1. Successful development of an effective in& apaci-Lcting agent could provide a capability to gain a militaryadvantage, but with fewer casualties than is possible throu, :hthe use of conventional, lethal chemical, or nuclear w»apons.

The US currently does not have an effective operationalincapacitating chemical capability.

I58h8$

32

2. Because they are non-lethal it may be possibleto make these agents acceptable in world public opinion as'being more humane than conventional or nuclear weapons.

3. Eliminating a first-use option without compen-sating political or military gains may unnecessarily deprivethe US of a means of engaging in armed conflicts witn resultantfewer casualties than in conventional war.

Cons:

1. First-use of incapacitating chemicals wouldprobably be construed by most nations, including some USallies, to contravene international law and the GenevaProtocol and to be contrary to past expressions of USpolicy. "

2. First-use could lead to escalation to lethalchemical or biological warfare (if the enemy force had thecapability) since the enemy might well not acknowledge anydistinction between incapacitating and lethal agents.

3. First-use of incapacitating chemicals couldlead to a loosening of international constraints on CW andBW, make effective arms control measures more difficult andprobably bring the US considerable international and domesticcriticism.

F. Should'the US maintain an o tion for unrestricteduse of RCA's in warfare and continue racticin this o tionin Vietnam? (The discussion below excludes peacetime use byUS forces for crowd control and base security which is notprohibited by the Geneva Protocol or international lawgenerally. )

Pros:

1. In many military situations, use of RCA cancontribute to military effectiveness; reduce US, civilianand enemy casualties and fatalities; decrease the destruction

':DOD does not believe such would contravene int!ernation::1 1aw.

- 33

of civilian housing and public facilities; increase the possi-bilities of the capture of PWs; and impede enemy avenues ofapproach.

Cons:

1, The use of tear gases in combat situations couldblur the "no first-use" doctrine and ultimately contribute toa lowering of barriers against use and proliferation of CW

capabilities in general.

2. Use of tear gases in Vietnam as an adjunct tolethal weapons may be construed by some to be contrary to pastUS official statements on use of tear gases in Vietnam.

3. The useof tear gases in war (even if limited tohumanitarian purposes) has been considered by man nations tobe contrary to customary international law and by most to beprohibited by the Geneva Protocol.

G. If the US maintains an o tion for the use of tearas in war should it be limited to "humanitarian ur osesu?

Pros:

1. Would permit the US to ratify the Geneva Protocolwith a public interpretation that would. create a minimum ofinternational opposition.

*"Humanitarian purposes"has never been clearly defined.By way of illustration, however, the use of tear gase in Viet-nam would be authorired where civilians and enemy forces werethought to be intermingled and the purpose of using tear gaswas to save civilian lives. Tear gas would not be authorizedwhere the primary purpose was to deny enemy troops cover orconcealment and make conventional weapons such as artillery orairstrikes more effective. OSD/JCS believe that no "humani-tarian purpose" doctrine on the use of weapons exists.

- 34

2. Wartime use would be allowed in much the sameway us riot control agents are used in time of peace, allow-ing for broader use than most restrictive interpretations ofthe Geneva Protocol would permit.

3. Maintaining this option. would help us to explainour use of tear gas in Vietnam as consistent with our inter-preta tion of the Geneva Protocol.

Cons:

l. If accepted, the military might well have to berestricted to use of tear gas in wartime to crowd controland base security which would deprive the military commanderof the most useful military applications of tear gas.

2. Implementat ion of this principle would castdoubt on the legality of our present use of tear gas inVietnam.

3. "Humanitarian purposes " is a term difficult todefine conclusively and field commanders and others would beconstantly beset by doubts about particular proposals fouse tear gas, especially if its use would save the lives oftheir own troops, perhaps at the possible expense of thelives of the enemy. ~

H. Should the US retain a olic ermittin first-useof chemical herbicides? (There is agreement that use ofherbicides as a defoliant is not contrary to internationallaw and is less likely to have international repercussionsthan usc against crops. Thus the main issue centers on anti-crop use. Some believe that further research is required atleast on possible long-term ecological effects of herbicides,and on such effects on human embryos-as has led to the recentreaffirmation and extension of the policy banning the use ofAgent 2, 4, 5 T in populated areas of CONUS and in Vietnam. )

'ACDA believes that workable rules of engatement could beissued which, at a minimum, prohibited use of RCA's in con-junction with conventional weapons such as artillery or airstrikes to facilitate killing of enemy troops. OSD/3CS dis-agree s.

- 35

Pros:

1. Herbicides have been used effectively in Vietnamto clear the sides of roads, canals and rivers and aroundencampments, thereby reducing the possibility of enemy ambushand concealment, and providing more protection to US and SVNforces.

2. Herbicides have been used effectively in Vietnamto destroy crops, thereby making it more difficult for theenemy to secure food supplies.

Cons;

The use of herbicides in an anti-crop role blursa "no first-use" doctrine.

2. If the US continues to take the position thatthese agents are excluded from a "no first-use" policy, itcould make international control of CM more difficult.

3. It is difficult to determine that crops are solelyfor the consumption of the armed forces which is the soletarget sanctioned by international law.

I. Should the use in war of all chemical and biolo icala ents includin tear as riot control a ents and orherbicides re uire Presidential authorization?

Pro:

The political implications of the unrestricted useoI tear gas and/or herhicides in war could be of such magni-tude that it would be unwise to have them introduced withoutPresidential authority.

Cons:

1. These non-lethal weapons should not be singledout of the US arsenal for special authorization.

2. This type decision should be predelegated inorder for adequate planning and logistics support, if RCA isto be used.

d

36

1III; The Geneva Protocol of 1925

A. The Geneva Protocol of 1925: "Protocol for theProhibition of the Use in War of As h xiatin Poisonous orOther Gases and of Bacteriolo ical Methods of Warfare. "

The position which the US Government takes withrespect to the Protocol will depend upon:

1. The decisions reached on the policy issuesdescribed above, and in particular t' he decision with respectto tear gas; and

2. Legal interpretations of the scope and statusof the Protocol which are considered at the end of this section.

B. ~Bk ldld

1. At present, 84 States are Parties to the Genevaprotocol, including the USSR and Communist China. All majorStates are Parties except the United States and Japan. * TheUnited States signed the Protocol in 1925 but never ratifiedit. In operative part, the Protocol aeads as follows:

"Whereas the use an-war of asphyxiating,poisonous or other gases, and of all analogousliquids, materials or devices, has been justlycondemned by''the general opinion of the civilized.world;

"Whereas the prohibition of such use hasbeen declared in Treaties to which the majorityof Powers of the world are Parties; and

"To the end that this prohibition shall beuniversally accepted as a part of Interna-tional Law, binding alike the conscience and thepractice of nations;

*Since 1965, 20 States have become Parties to the Protocoland Japan has recently indicated its willingness to con-sider ratification.

37

"Declare:

"That the High Contracting Parties, so far asthey are not already Parties to Treaties prohibit-ing such use, accept this prohibition, agree toextend this prohibition of the use of bacteriologi-cal methods of warfare and agree to be bound asbetween themselves according to the terms of thisdeclaration. "

2. Thirty-nine States accompanied their ratifica-tions with reservations or declarations which declare theprohibitions of the Protocol, as to the reserving State, tobe inapplicable as to non-Signing States or toward SigningStates which have first violated its provision (i.e. , "nofirst-use") . Some reservations also include "Allies ofSigning States"in this exception.

3. Since many States (including the United Kingdom,France and the USSR) have ratified with reservations, theUnited States may wish to add a "standard reservation" similarto the operative portions of prior reservations relating to"no first use" and "allies". Although there is no consensusas to the scope and exact language of a proposed U. S. reser-vation, all agree that ratification by the U. S. should beaccompanied by a reservation which limits the undertaking toa "no first use", but would permit retaliation in the eventof use by another state or its allies.

4. If the United States ratifies the Protocol, itwill probably be desirable to include with ratification (andany reservation which it might wish to make) an interpretivestatement. Such a statement would set forth the UnitedStates position and interpretation as to the Geneva Protocol'seffect on the use of C agents such as herbicides, defoliants,the use in warfare of RCA 's, and any other points which requireinterpretation. Interpretive statements which differ fromgenera lly accepted interpretations of the Protocol may beconsidered by Parties as reservations subject to acceptanceor rejection.

- 38-

5. Ratification would not prohibit, restrict, orregulate any research and development, production, deployment,and stockpiling of chemical and biological weapons deemednecessary by the United States.

C. Should the US ratif the Geneva Protocol of 1925"Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of As h xiatinPoisonous or Other Gases and of Bacteriolo ical Nethods of

l. A reservation or inte retive statement~er-mittin the United States to use chemical and biolo icalinca acitatin . a ents (Presumably such a reservation/inter-pretation also would include tear gas and other non-lethalRCA's for which pros and cons are in PP2 below. )

Pro:

It would make clear our intent to preserve the option,wherever necessary and appropriate, to employ incapacitatingagents to reduce overall casualties.

Cons:

(a) Ratification under such conditions would runcontrary to the expressed views of nearly all other membersof the international community and adherents to the Protocol,and is likely to be rejected by many Parties to the Protocol,thus raising serious questions whether ratification wouldadvance US interests.

(b) First use of chemical or biological incapaci-tants would be viewed by many &ountries as contrary tocustomary international law and any attempt to reserve anoption for such use as legally ineffective.

(c) It could be construed as inconsistent withpast US statements of policy. ~* Legal issues underlying the pros and cons are discussed

in Section E, below.**DOD does not believe that past US official statements of

no-first-use of lethal agents apply equally to non-lethalagents.

- 39

2. A reservation or inter retive statementermittin the United States to use- tear as and other

non-lethal RCA's in wartime without restrictions?

Pros:

(a) It would accomplish the positive step of rati-fying the Protocol while at the same time preserving for theUnited States the wide latitude for the military use in war-time of tear gas and other non-lethal RCA's, ensuring thatwhenever necessary and appropriate, we would have the optionto employ some non-lethal agents instead of other more lethalmeans of warfare.

(b) Ratification would signal US interest in rein-forcing the barriers against CBW, and could enhance the USposition as regards the possible initiation or negotiationof any further arms control measures in the CBW area.

(c) A reservation or interpretive statement orboth is desirable to clearly state that we do not regard ouruse of RCA's and herbicides in Vietnam as contrary to theProtocol.

(d) Such a reservation or interpretive statementwould coincide with the practice in Vietnam of the US andcertain of its allies (Republic of Vietnam, Republic ofKorea, Thailand and Australia, the last two of which areparties to the Protocol. )

Cons:

(a) Ratification under such conditions would becontrary to the view of many members of the internationalcommunity and Parties to the Protocol that unrestrictedmilitary use of tear gas and other non-lethal RCA 's in war-time is prohibited by the Protocol. Ratification under sucha statement of interpretati'on might be regarded by Partiesto the Protocol as an attempt to change the actual nature ofthe existing obligations.

, OADR

- 40-

(b) Ratification under such restrictions wouldlimit "first-use" options for CW and BW incapacitatingagents which have some military vaIue.

(c) It could be construed as inconsistent withpast US official statements. *

3. An inter retive statement or reservationsettin forth the United States view that the Protocol doesnot rohibit the use of tear as and riot control a ents inwartime for "humanitarian ur oses. "?

Pros:

(a) It would preserve some latitude for the useof tear gas and other non-lethal RCA's in wartime for genuinehumanitarian purposes.

(b) Ratification would: (i) strengthen the legalforces of the Protocol and international restraints on theuse and proliferation of CW and BW agents; (ii) be inter-preted as a positive, welcome step by the internationalcommunity; (iii) reinforce. past US official statements onthe "no first-use doctrine"; (iv) reaffirm past US votesin favor of resolutions calling for strict adherence to theprinciples and objectives of the Protocol; (v) and couldenhance the US position as regards the possible initiation '

or negotiation of any further arms control measures in theCBW area.

Cons:

(a) Ratification under these conditions, becauseof the difficulties of actually determining "humanitarianpurposes", would, of necessity, tightly restrict the militaryuse of tear gas and other non-lethal RCA 's in wartime effec-tively limiting their use to crowd control and base security.In some cases where non-lethal agents might otherwise be used,lethal conventional weapons would have to be employed instead.

* DOD does not believe that past US official statements ofno-first-use of lethal agents apply equally to non-lethalagents.

lj:~SLING il

QADR

- 41

(b) Ratification under such restraints wouldrestrict "first-sue" options for non-lethal RCA's and CW

and BW incapacitating agents which we might wish to retain.

(c) A ratification without an interpretive statementregarding RCA's and herbicides (i) could lead to doubts onthe legality of our present use of tear gas in Vietnam and(ii) preclude future use of this weapon with the consequentloss: of its military value.

4. "Without an attem t to ex ressl reserve theri ht to use RCA's in war?"

Pros:

(a) Ratification without additional reservation orinterpretation would accord with the view of many States thatthe widest latitude ought to be given to the prohibitions ofthe Protocol.

(b) Ratification would: (i) strengthen the legalforce of the Protocol and international restraints on theuse and proliferation of CW and BW agents; (ii) be inter-preted as a positive, welcome step by the internationalcommunity; (iii) reinforce past US official statements onthe "non first-use doctrine"; and (iv) reaffirm past USvotes in favor of resolutions calling for strict adherenceto the principles and objectives of the Protocol.

(c) Ratification would signal US interest in re-inforcing the barriers against CBW, and could enhance the USposition as regards the possible initiation or negotiationof any further arms control measures in the CBW area.

Cons:

(a) A ratification without an interpretive state-ment regarding RCA's and herbicides (i) could cause gravedoubts on the legality of our present use of tear gas in

- 42

Vietnam+ and (ii) preclude future use of this weapon withthe consequent loss of its military value.

(b) In the view of many members of the interna-tional community and Parties to the Protocol, it wouldrestrict certain "first-. use" options for tear gas, othernon-lethal RCA's in wartime, and CW and BW incapacitatingagents which we might wish to retain, ruling out the useof these agents even for "humanitarian purposes".

D ~ Should the United States decide not to ratif theGeneva Protocol choosin erha s to make official ronounce-ments reaffirmin United States CBW olic ?

Pros:

l. It would avoid taking any firmer official posi-tion on the Protocol, particularly before the Senate duringthe ratification process, which might result in a restrictiveinterpretation of the Protocol and deny useful military options.(State and Defense differ over the scope of the prohibitionsin the Protocol. See legal views at.the end of this section. )

2. Ratification is not strictly necessary toestablish US support for the principles and objectives ofthe Protocol in view of- past official statements supporting.and announcing adherence to those principles and objectives.

* This disadvantage could be overcome if the decision wereaccompanied by a statement indicating this was a unilateralpolicy change not required by international law. , (ACDA)

This disadvantage may, in part, be justified by an officialpronouncement declaring that the United States has made aunilateral policy change toward the legal content of theGeneva Protocol. On the other. -hand, such an official pro-nouncement would not overcome the propaganda effects whichunfriendly States would enjoy. As such, an official state-ment of this kind would be harmful rather than beneficial (DOD)

- 43

3. It would avoid the disadvantages of ratifyingthe Protocol with a reservation that might not have inter-national acceptance.

Cons:

1. Non-ratification would be regarded by manynations who are aware of our current policy review as repre-senting a negative outcome to this review, and would leaveus vulnerable to propaganda exploitation by the Soviet Union.

2. Non-ratification would be seen as a blow toprogress in disarmament and arms control measures in theCBW field.

3. Non-ratification would represent loss of anopportunity to: (a) strengthen the legal force of the Pro-tocol and international restraints on the use and prolifera-tion of CW and BW agents; (b) take a positive step, whichwould be welcomed by the international community; (c) rein-force past US official statements on the "no first-usedoctrine"; and (d) reaffirm past US votes in favor of resolu-tions calling for strict adherence to the principles andobjectives of the Protocol.

E. ~LL 1

1. The De artment of State

(a) While the interpretation of the GenevaProtocol, as qualified by standard reservations, is no! freefrom ambiguities, the most persuasive interpretation is thatit .prohibits the first-use in warfare among parties of (i)all biological weapons and agents and (ii) all chemical agentsand weapons except (i) herbicides and (ii) those riot-controlagents widely used for domestic law enforcement purposes whenthey are used for "humanitarian purposes. " Most States,including the US in officx!I statements at the UNGA in December1968 and at the CCD, maintain that the term "bacteriological"in the Protocol includes all "biological" agents and weapons .

(b) While use of "asphyxiating" and "poisonous"gases is clearly prohibited by the 1925 Protocol, the term"other gases" is ambiguous. Some have suggested that a dis-tinction may be drawn between lethal and non-lethal chemicalagents. However, there is no basis in the negotiating historyof the Geneva Protocol for making this distinction. In addi-tion, there is no ob jective way to differentiate lethal fromsupposedly non-lethal chemical weapons. Many States, and theSecretary-General oz the United Nations, interpret the words"other gases" in the Protocol as prohibiting the use in war-fare of any C weapon or agent, including herbicides and teargas, under all circumstances The United States, speakingthrough the US Ambassador to the United Nations, has takenthe position that the Protocol does not prohibit the use inwarfare, for humanitarian purposes, of anti-personnel C gaseswhich are widely used by governments to control riots by theirown people. Today, this would permit the use of tear gas forhumanitarian purposes, since it is the only riot-control agentpresently widely used by governments domestically.

(c) The central purpose of the Protocol ishumanitarian--to prevent the use-of a class or classes ofagents in warfare that cause unnecessary suffering. Wided1&mastic use of tear gases for riot control purposes and theabsence of permanent. or long-term damaging effects provide

-45-

grounds for arguing that use of these agents in warfare is notinconsistent with the purpose of the Geneva Protocol. Theprimary rationale for an interpretation amounting to s totalban on chenical agents--that there is no reliable and non-controversial distinction between legal and illegal agents onthe basis of their harmless nature--may be overcome if legalagents are limited to those widely used by governments fordomestic law enforcement purposes. Moreover, the humanitarianpui poses of the Protocol are not offended, but rather furtheredwhen these agents are used in combat in a manner calculated toreduce enemy and civilian casualties. It cannot, nowever, beargued that use of these agents in conjunction with otherweapons to facilitate the killing or wounding of the enemyfurthers the humanitarian purposes of the Protocol. Any attemptto distinguish between the use of poisonous gas itself tocreate casualties, and the use of non-poisonous gas. in conjunc-tion. with other deadly weapons to create casualties, is notpersuasive in the context of the purposes of the Protocol, andwould almost certainly be widely condemned.

(d) The Department of State has also taken theposition that the principles of tne Protocol have become partof customary international law. Thus, in Congressional corres-pondence in 1967, it was stated that "We consider that thebasic rule set forth in this document has beenso widely accepted over a long period 'of time that it is nowconsidered to form a part ot customary international law. '"While the establishment ot these principles as customary inter-national law is not free from doubt, this conclusion is basedon th» practice and statements of States, including the UnitedStates, and the nature and purpose of the Protocol. Mostrecently, over 90 States, including the United States, havevoted for UN resolutions (in 1966 and 1968) that demand strictand unconditional compliance with the "principles and objectives"of the Protocol. The establishment oi the principle of theProtocol as customary international law renders inoperativereservations of some States which seek to apply the Protocolonly to other Contracting 'States . All States, whether or notParties to the Protocol, are bound to observe rules of customaryinternational law.

, QATAR

- 46-

(e) Some have argued that there is no "humani-tarian purposes" limitation either in the Protocol or undercustomary international law on the ways ~n which RCAs can beused in warfare. The United States has /sought to establish a

4'+

broader exception that would permit the use of such agents inconnection with conventional fire to kill enemy troops. Moststates which have expressed views and the Secretary-Generaltake the position that the Protocol prohibits any use of teargases fLn warfare. Accordingly, if the United States determinesto ratify the Protocol and wishes to maintain the option touse tear gas "for humanitarian purposes, " an express interpre-tation to this effect should accompany ratifications. ':

(f) If the United States were to determine tomaintain the option for unrestricted use of tear gas andother incapacitants, it would be necessary not only to include(with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate) anexpress interpretation or reservation to this effect in rati-fying the Protocol, but also to take the position that theUnited States does not recognize any customary internationallaw restriction on such uses and to oppose UN resolutionsevidencing such a customx y law limitations.

2. The De artment of Defense

The Department of Defense does not a'gree withthe Department of State position that the Geneva Protocolnow states principles of customary international law andthat its prohibitions extend to the type of agents now beingemployed by the United States in Vietnam.

First, the Protocol language, itself, onlypurports to bind the Parties "as between themselves, " andt he many reservations limiting its application furtherdeprive it of any general law declaring effect and convert

"It is State's view that if this position is adopted, anypublic statements on the extent of the United Statesobligations under customary international law could andshould be avoided.

- 47

it into a confusing array of contractual relationships.That there is, at the least, major disagreement on theProtocol's legal effect is reflected in the UK study tabledat the ENDC in Geneva in August 1968:

"(ii) Jurists are not agreed whether theProtocol represents customary internationallaw or whether it is of a purely contractualnature. "

The reason for this di.sagreement is obvious.The reservations to the Protocol create the followingcongeries of differing contractual relationships, dependingupon the substance of the reservation, and upon whether otherratifying States have accepted or objected to the reservations.

(a) States which have ratified the Protocolwithout reservations have an unqualified commitment with allother such States, in which no use of the prohibited weaponsis legal, except, the limited right of reprisal.

(b) All States taking reservations concern-ing non-party States have qualified their obligations topermit use against a State which is not a party.

(c) Reserving States have qualified their.legal obligation so that a use of the prohibited weapon islegal if another State or its allies have' first used itagainst them. The language of the reservations regardingthis "second use" however, is not clear, i.e. , whether anyand all CW or BW agents may be employed as a second use orwhether the second use is limited to the specific CW or BW

agent used by the first using State.

(d) All States which have objected to theState or States making reservations, have either preventedthe Protocol from coming into force between them, or haveestablished a contractual relationship modified in termsof the reservation and objection.

y MkkMhaP 8 i

- 48

These varying contractual relationships,which confuse the interpretation and application of the GenevaProtocol, clearly show that the States which have ratifiedit did not intend to declare rules of customary internationallaw. Further, they deprive the Protocol from being anadequate "source" of customary international law. Thisconclusion is buttressed by a recent study conducted forACDA by the noted publicists Ann and A. J. Thomas, ofSouthern Methodist University School of Law. After survey-ing the confusion, they concluded:

"The best that can be said, therefore,of the Geneva Protocol is that. it doesnot constitute a completely legalobligation even between its signatories.It establishes a whole host of legalregimes which seem to be impossibleto untangle. " (At page 102)

Second, while it is true that thepractice of States since the 1925 Protocol has generallyshown compliance coinciding with its: provision, there is noevidence to show that such compliance was based on ~le alrestraints rather than ~olio reasons, facts which must beshown to deduce a rule of law from State practice. Nor isthere evidence to show that compliance was necessarily linkedto the Geneva Protocol. Indeed, the United States represen-tative recently stated categorically in the United Nationsthat the United States considered that non-use of C&B agentsduring WW II was based upon the fear of retaliation ratherthan on the Protocol's legal restraint. (Ambassador Fisher,November 27, 1967.)

Finally, recent discussions of Westerndisarmament expects in NATO (US Mission NATO 4454) demon-strates no consensus on the subject of whether or not theGeneva Protocol now states customary international law.Only the Netherlands was willing--to come out affirmatively

Q&

5%

ee%5SNAia

- 49-

on this point. The UK opinion was that there was "someevidence" of a customary rule, while Italy and Belgiumexpressed doubt. Denmark stated categorically that no suchcustomary rule existed.

Third, with regard to the type of agentswhich are prohibited by the Protocol, the DOD agrees with theDOS that the Protocol language is ambiguous. The DOD is ofthe further view that the Protocol does not prohibit the useof incapacitants, RCA, herbicides- or- defoliants.

There is, in fact, considerable disagree-ment among States on the Protocol's coverage, i.e. , whetherall gases, or whether only those which are lethal in natureare prohibited. This is a matter which is not resolved bythe Protocol. A UK study tabled at the ENDC in August 1968,stated, in this regard:

"(IV) There is no consensus on themeaning of the term "gases" in the phrase"asphyxiating, poisonous or devices. "The French version of the Protocol renders"or other" as "ou similaries" and thediscrepancy between "other" and "similaries"has led to disagreement on whether non-lethal gases are covered by the Protocol. "

The Department of Defense view issupported not only by the Practices which have been sanctionedby the United States Government for the use of RCA in Vietnam,but also by many statements of policy by United States'officials on these practices. -These statements demonstrate,contrary to the DOS position, that taken as a whole, USjustification of its use of RCA 's in Vietnam is that theseagents are not banned by the Protocol or by internationallaw--not on the narrow ground that a "humanitarian purpose"exception exists. Further, .there is no evidence that thisdistinction proposed by the Department of State--that riot

- 50-

control or incapacitants may be used in warfare only for"humanitarian purposes"--has been accepted by all or evena majority of States. The negotiating history of theProtocol does not show that this doctrine of "humanitarianpurpose" was even considered by i.ts draftsmen. In the DOD

view, use of RCA's or inca acitants is either rohibited bthe Protocol or it is not. There is no basis for theargument that their use is permitted for "humanitarian"purposes and prohibited for all others.

The Department of Defense view is thatthere are no rules of customary international law whichprohibit, per se, the use of any chemical agent reasonablyemployed to secure a military objective, other than thegenerally accepted principle that weapons shall not be usedagainst non-combatants or to cause unnecessary suffering,and those rules which state that a soldier who is hors decombat is not a lawful target under the laws of war.Whether or not the enemy is hors de combat, however, is afactual and not a legal question. There is no rule whichsays that gases and conventional weapons cannot be usedtogether. There is, instead, the above~entioned test tobe applied on a case-by-case basis to the facts. Thisposition is in accord with that developed by Thomas andThomas for ACDA (pp 171-173), referred to above. There isno support for the DOS argument that CW or BW agents--orany other weapon--shall be used "only for humanitarianpurposes" i.e. , only to save lives or reduce casualties.

With respect to biological agents theDepartment of Defense takes the view that the term "bacterio-logical" is vague and ambiguous and was not intended toencompass organisms which are not "bacterial" in nature.Other biological organisms such as rikettsiae, viruses andfungi under this view do not fall under the Protocol'sprohibition.

This view .i's supported by the "draftconvention on biological warfare" tabled by the United King-dom at the ENDC in June 1969, the purpose of which is to

- 51

overcome the ambiguous provision in the Geneva Protocol con-cerning "bacteriological" warfare-. The United Kingdom con-siders this term "not sufficiently comprehensive to includethe whole range of microbiological agents. "

Additionally, since the Protocol pro-hibition of "bacteriological methods of warfare" is onlyan extension to such agents of the basic Protocol prohibi-tion, the same rationale as set forth above with respectto chemical agents would apply to incapacitating bacterio-logical agents. Hence, such agents are considered to bebeyond the reach of the Protocol.