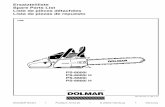

Ps Tsoh106

-

Upload

david-beagin -

Category

Design

-

view

530 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Ps Tsoh106

eith and Steven Martin, ages 5 and 3, are two contented,joyful little boys. It’s a sunnyTuesday morning when their

father, Loran, brings them to Penn StateChildren’s Hospital for their regularcheckups at the Stem Cell OutpatientClinic on the seventh floor.

To watch them play in the children’splayroom, just across a toy-filled lobby,you’d never know that both of them suffered from the same life-threateninggenetic disease. Not so long ago, theyhad a delicate procedure performed tosave their lives. The brothers fromNewville, Pa., were born with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), an immuno-deficiency disorder.

Normally, the immune system useswhite blood cells and antibodies to attack potentially harmful substances.Immunodeficiency means that theimmune system fails to protect the body.The disorder causes increased infection,more severe reactions, and delayed recov-ery from sickness. Those suffering fromimmunodeficiency are also more proneto developing cancer.

DiagnosisThe road from diagnosis to recovery

has been a rough one for Loran and hiswife, Selesti. When the Martins’ secondchild and oldest son Keith was 4 weeksold, Selesti noticed a large bruise on hisbody as she was changing him.

Concerned, the Martins took him totheir family physician. They were told totake Keith to the local emergency depart-ment if he didn’t improve. The bruisefaded, but other sicknesses such as con-tinual ear infections, asthma, skin rashes,pneumonia, and bloody diarrhea plaguedKeith. At 8 months, while Keith was inthe hospital to have tubes placed in hisears, blood work revealed the source ofthis young baby’s ailments: WAS. Keith’sdoctors immediately referred the Martinsto Penn State Children’s Hospital. Hisdoctors prescribed a stem cell transplant.

What is stem cell transplantation?In addition to immunodeficiency disor-

ders, stem cell transplants are used to treatpatients with cancer, leukemia, aplasticanemia, and disorders of hemoglobin pro-duction. “The sources of stem cells fortransplant include bone marrow, umbili-cal cord blood, or stem cells collected fromthe blood,” explains Kenneth G. Lucas,M.D., director of the transplantprogram, Penn State Children’sHospital. Here, stem cells are producedand mature to become red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

KMeet Keith and Steven of Newville, Pa.

Spring 2006

Taming Tantrums........2 Help for Eating Problems.........4 Baby Walker Warning........6 Volume 12, Number 1

Steven and Keith Martin play in the Children’s Hospital playroom.

continued on page 2

2 Penn State Children’s Hospital, www.pennstatechildrens.com

As they grow, they are released into theblood to perform their specific functions.

In the process of stem cell transplanta-tion, the patient receives high doses ofchemotherapy and/or radiation to destroyunhealthy bone marrow cells. Stem cellsthat have been collected from a donor’sbone marrow are then given back torestore the body’s production. The cellsare transplanted through a broviac line,inserted surgically in a central vein beforetransplant. The central line allows allfluids and medications to be administered

through the same line, eliminating theneed for multiple intravenous sticks.

For patients with immune deficiencylike Keith, transplant provides healthycells capable of fighting infection. Thosewith leukemia receive cells free of disease.In cancer patients, stem cell transplantsallow patients to receive higher levels ofchemotherapy or radiation therapy thanwould otherwise be possible. Transplantis used most often in cancer patientswhen conventional treatments havebeen unsuccessful in destroying all ofthe cancer cells, or when patients experi-ence a return of their cancer, known as arelapse. The higher doses of chemother-apy kill all of their bone marrow cells,but a transplant replaces the cells withhealthy ones.

Two different sources for stem cell trans-plants exist. Allogeneic transplant stemcells are collected from either a matchedrelated donor, a matched unrelated donor,or from cord blood. Autologous transplantstem cells are collected from the patientprior to transplant. This type of transplantis used most commonly with patients whohave relapsed solid tumors including neu-roblastoma, brain tumors, and lymphomas.

A different childIn November 2000, 1-year-old Keith

received an allogeneic stem cell transplant,with his 21/2-year-old sister, Grace, serving as donor. After the transplant, Keithremained in the hospital for a few weeksto allow the cells to engraft. At first, theMartins didn’t notice much difference.But suddenly in January 2001, the Martinsnoticed a dramatic, positive change. “Hewas just a different child,” says Selesti.

Déjà vuOne year later, the Martin family

welcomed their third child, Steven.Physicians performed tests immediately tosee whether he also had the gene for WAS.The tests were positive. “This time, we sortof knew what was coming,” says Selesti.“It was easier and it wasn’t—because weknew what was coming.” Even though thesame ailments that plagued Keith hauntedSteven as well, as a whole, he was ahealthier child than Keith.

Steven received his stem cell transplantwhen he was 2 years old. The stem cellswere harvested from the Martins’ fourthchild—a newborn sister whose umbilicalcord provided the cells. Selesti says the

Keith and Steven, continued from page 1

Trishia Layden, R.N., takes Steven’s blood

pressure. “They’re our most well-behaved

patients,” she says.

our little one is having a kick-ing, screaming mega-meltdownin the frozen-food aisle. Andyou’re sure everyone in the

market is thinking, “Why is that childcarrying on, and how come the parentisn’t doing something to stop it?”

The period from 14 to 30 months is a peak time for tantrums, says LynnWegner, M.D., F.A.A.P., a developmentaland behavioral pediatrician and adjunctprofessor at the University of NorthCarolina in Chapel Hill. Toddlers that age are learning to verbalize their feelings.

Young children whose “wants” arebeing blocked are apt to lose control,especially when hungry, tired or over-stimulated. Parents in a chaotic publicsetting, focusing on the task at hand, are

less likely to notice shifts in their child’smood. This means they may miss thechance to defuse matters before a full-blown tantrum breaks out.

Preventing a tantrum is mucheasier than stopping one. So beforeyou step out with your child:■ Try to plan your outing for a time

when crowds are few. That helps youavoid long lines and reduces embar-rassment if it all falls apart anyway.

■ Ensure you and your child are well-fed,comfortably dressed and rested beforeyou leave.

■ Offer some run-around time before youconfine your child to a shopping cartor stroller.

■ Bring toys, snacks or books to entertainand distract if need be.

Even with preparation and plan-ning, tantrums are bound tohappen at times. When they do:■ Make sure the environment is safe if

your child is kicking, flailing, or throw-ing things. Remove the child if sharpcorners, breakables or other objectspose injury risks.

YTechniques for Taming TantrumsTake steps to avoid them, but if that fails, know what calms your child

Penn State Children’s Hospital, www.pennstatechildrens.com 3

Spacers on Inhalers Curb Asthma AttacksFighting a child’s asthma attack could be as simple as sliding a plastic tube onto the endof an inhaler, University of Florida researchers say. Yet a lot of doctors don’t give parentsthis option, they add. The plastic tube is a holding chamber, or spacer. Using a metered-dose albuterol inhaler with a spacer and increasing the number of puffs to treat breath-ing trouble works as well as a nebulizer, studies show. It also causes fewer side effects.“Most doctors and patients misbelieve that a nebulizer is more effective than an inhaler,”says Florida professor Leslie Hendeles, Pharm.D., lead author of a report in the AmericanJournal of Health-System Pharmacy. A nebulizer turns albuterol into a fine mist thatpatients breathe in through tubes. An inhaler uses albuterol at a lower dose. The spacermakes the inhaler more effective.

Air Bags Can Harm Kids 14 and UnderChildren 14 and younger shouldn’t sit in the front seat of cars with air bags, says a studyin Pediatrics. Federal rules say carmakers must warn of a risk for air bag injuries for chil-dren 12 and younger. But researchers looked at an eight-year sample of 3,790 childrenages 1 month to 18 years who were seated in the right front seat during crashes. Thestudy found kids 14 and younger were at high risk for serious injury from air bags. Airbags tended to protect children ages 15 and up. “When my 13-year-old nephew wantsto sit in the front seat now, I won’t let him,” says study lead author Craig Newgard, M.D.,an emergency medicine researcher at Oregon Health & Science University.

Inactive Girls Gain WeightInactive teen girls gained an average of 10 to 15 pounds more than active girls during a 10-year study, The Lancet reports. At ages 9 and 10, there were slight differences in body mass index—about 4 to 5 pounds—between active and inactive girls. But the gap grew by the time the 2,379 girls in the study turned 19. The girls’ calorie intake rose just a bit and did not seem to be tied to the weight gains. “Just preventing the decline in physical activity that currently occurs among adolescent girls may be enough to prevent obesity,” says research nutritionist Eva Obarzanek, Ph.D., of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

[ health bits ]

Kids’ Shots Are Often LateNearly two out of five U.S. children are “under-vaccinated” for more than six months during their firsttwo years of life, a study found. “It’s really importantthat kids get vaccinated on time, especially during thefirst two years, because that’s when they are at highestrisk for many of the vaccine-preventable diseases,”says study author Elizabeth Luman, Ph.D., a NationalImmunization Program disease expert. Children needabout 15 to 20 shots to head off measles, mumps,chickenpox, and the like before their second birthday.While 73 percent of children get all the shots they need, just 9 percent get themall on time, researchers wrote in the Journal of the American Medical Association.To check the vaccination schedule, ask your doctor or visit www.cdc.gov/nip.

■ Remove your child if you want to avoiddisturbing others or ease your ownstress. It may be easier to calm the childin a quiet place.

■ Don’t worry about other people’s reactions. Focus on your child, Wegnersays. Pick actions based on your child’sunique needs and temperament. Someyoungsters respond to being held or toa parent’s calm,repetitive words.Others do bestwith watchfulwaiting.

■ Stay centered,take deep breathsand remember:This too shallpass. Hopefully,soon! ❖

improvement was more gradual in Steven.Today, both he and his big brother aredoing fine. Steven returns to Penn StateChildren’s Hospital every three monthsfor checkups, while Keith visits every sixmonths. By the smiles on their faces, theydon’t seem to mind. ❖

Steven with his brother Keith

To Learn More

For more information aboutStem Cell Transplantation atPenn State Children’s Hospital, visit www.pennstatepediatricstemcell.com.

oes your child throwtantrums at the dinner table?Eat chocolate pudding and only chocolate pudding?

Maybe your child is physically inca-pable of chewing and swallowing. If any of these scenarios sound familiar,the Feeding Program at Penn StateChildren’s Hospital may be the answer.

Keith Williams,Ph.D., director of the FeedingProgram at PennState Children’sHospital, and hisstaff are committed tohelping children witha range of feeding andnutritional problems.

The program atChildren’s Hospital is

one of only about a dozen comprehen-sive programs in the country, havingcared for children from 21 states andfour countries outside the United States.

One of those countries is Ireland,which doesn’t have a feeding programlike the one at Penn State Children’sHospital. Ann and John Cahill of AshlerTulla, Ireland, had given up hope aftertaking their tube-dependent daughterTinalee to doctors and feeding programsin Ireland. At the age of 6, Tinalee hadnever eaten solid foods or spoken asingle word. She was also still in dia-pers. Yet even after surgeries to correcther physical problems, Tinalee stillcouldn’t eat or speak. She had become

traumatized by food, associating it withpain, and her mouth muscles weren’tstrong enough to form words.

Children are enrolled in the FeedingProgram for a variety of reasons. Someregularly refuse food or exhibit signifi-cant behavioral problems, such asthrowing food or hitting, during meals.Others eat extremely limited varieties offoods or textures that are not develop-mentally appropriate, such as baby foodwhen they should be eating solids.Some children, like Tinalee, have moreobvious feeding problems, such as vom-iting after or during meals, or relyingon a feeding tube for nourishment.

But how do parents know if theirchild has a serious feeding problem thatneeds professional intervention or if it’ssomething they can handle themselves?Williams says that when children are

failing to thrive,it can affectheight, weight,and brain devel-opment, and it’sdefinitely time toget help. Parentsshouldn’t blamethemselves, headds. Most feed-

ing problems are a result of illness orother problems.

Children can be referred by their doc-tors, therapists, parents, nurses, andteachers. Ann Cahill found the FeedingProgram at Children’s Hospital onlineand decided to call Williams in a

last-ditch effort. Williams asked Cahillto send Tinalee’s medical records and avideo of her trying to feed her daughter.He called the Cahills within two weeksand said that Children’s Hospital wouldwelcome Tinalee into the program.

In June 2004, Ann and Tinalee flewstateside while John stayed home withtheir two other children. After a week ofintensive therapy, Tinalee was takingher first bites of solid foods, requiringonly water through her feeding tube. In one month, Tinalee was completelyoff the tube. “It was a huge, unrealchange,” says Ann.

Tinalee was enrolled in the intensivetreatment program, an all-day alternativeto inpatient therapy used for childrenwho are dependent on supplementalfeedings or at severe nutritional risk.Intensive treatment entails between fiveand 10 feeding sessions per day.

Helping children with feeding and nutrition

D

4 Penn State Children’s Hospital, www.pennstatechildrens.com

Keith Williams,Ph.D.

Tinalee with motherAnn Cahill

Feeding Program

Bailey Ann Schwartz of Beach Lake, Pa.(in Wayne County), needed specializedcare for her systemic scleroderma. Sheand her family found assistance close tohome thanks to the partnership betweenPenn State Children’s Hospital andWyoming Valley Health Care System inKingston. Specialists from Children’sHospital regularly travel to WyomingValley to offer the care that area childrenneed. Services include the following:■ Cardiology■ Gastroenterology■ Hematology/oncology■ Nephrology/hypertension■ Pulmonology■ Rheumatology

Partnership HelpsWith Patient Care

To Learn More

For more information, ask you child’spediatrician or call Penn State Children’sHospital at (800) 243-1455.

Penn State Children’s Hospital, www.pennstatechildrens.com 5

Bailey Ann Schwartz

The feeding program also offers threeother treatment plans: outpatient feed-ing therapy, the oral motor clinic, andan evaluation clinic. Outpatient feedingtherapy is the most common treatmentand includes a single appointmentwhere therapists work with children totackle specific problems. The oralmotor clinic cares for children who arephysically unable to eat.

The multidisciplinary clinic featuresspecialists from pediatric gastroenterol-ogy, behavioral psychology, and manyother specialties. No matter the treat-ment plan, the goal is the same: teachingthe parents and caregivers how to main-tain their child’s healthy eating habits athome. Parents are able to watch feedingsessions in observation rooms attachedto each treatment room. In addition, ses-sions are videotaped with the therapistnarrating each technique. The session is

burned to DVD and sent home withthe parent or caregiver.

For the Cahills, the experience hasbeen life-changing. Tinalee has becomeindependent and vibrant, feeding her-self, using the bathroom, and speaking“loads of words,” says Ann. “She came tolife.” In addition, Ann has gone back towork part-time, and she and John can goout together again. “Before, everywherewe went, Tinalee came.” Now other care-givers are comfortable taking care ofTinalee. “We owe them so, so much.” ❖

To Learn More

For more information about how theFeeding Program at Penn State Children’sHospital can help your family, visitwww.hmc.psu.edu/childrens/feeding.E-mail: [email protected] (717) 531-7117

Babies Need“Tummy Time”Put infants to sleep on theirbacks, but act to avoid flatheads while they’re awake

High chairs are great for older children,

who can safely play with toys on a tray.

A simple piece of advice in 1992 cutthe death rate from sudden infantdeath syndrome (SIDS) by more thanhalf. That was the year the AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics (AAP) told parents to put babies to sleep on their backs.

Now, the experts have some newadvice to reduce the odds of flattenedheads, a possible result of babiesspending so much time on their backs.

No one’s sure how common flatheads are. Statistics vary a great deal,“from one in five cases for a mild formto one in 500 to 600 cases,” says AAPspokesman John Persing, M.D., a pro-fessor and chief of plastic surgery at

6 Penn State Children’s Hospital, www.pennstatechildrens.com

xtreme obesity plagues more thana million teens and young adults,experts estimate. The youths tendto be at least 100 pounds or 100

percent above their ideal body weight.So far, the toll for that extra weight

includes a sharp rise in type 2 diabetesamong the young. And the future maynot be any healthier for these teens, whoaren’t likely to grow out of their obesity.

What’s a parent to do? More and moreare looking at the same last resort asadults—bariatric surgery. Such surgery, ineffect, reduces the stomach’s size. Youfeel full sooner, so you eat less.

U.S. doctors did about 150 such pro-cedures on teens from 1991 to 2000, saysThomas H. Inge, M.D., Ph.D., surgicaldirector of the Comprehensive WeightManagement Center at CincinnatiChildren’s Hospital Medical Center. Noone’s sure how many have been donesince. Still, they’re clearly on the rise.About 60 teens have had the surgery justat Cincinnati Children’s since 2001.

But such surgery isn’t right for all obeseteens. In a recent Pediatrics article, Ingewrote that bariatric surgery is warrantedin most cases only when adolescents:

■ Have tried but failed at organized weight-loss attempts of six months or longer.

■ Have a body mass index (body weightadjusted for height) of at least 40.

■ Have finished most of their skeletalgrowth. That generally means girls mustbe at least 13 years old and boys 15.

■ Have obesity side effects that weightloss would help fix.

“If we sense a child is not ready to makea major change in his or her diet, or ifthey haven’t made a very valiant effortwith some sort of supervised weight-lossprogram for at least half a year, that’s areal red flag,” says Inge.

“If the child does not change behaviors,then the expected weight loss may notoccur or, with time, could be regained,”says Ronald Williams, M.D., directorof Penn State Children’s HospitalMultidisciplinary Weight LossProgram. Parents and children must alsounderstand the risk for complications,including the very slight risk for death.

Are you looking at such surgery for achild? Experts suggest you seek a centerexperienced in the procedure. The centershould have a weight-management teamwith experts in different fields—dieti-tians, psychologists or psychiatrists, andsurgeons—who can evaluate your child.

Long-term follow-up is a must. So is astrong commitment from you and yourchild. “The operation is a tool, not a cureor quick fix,” says Inge. “It takes lifelongcompliance with a dietary regimen, vita-min and mineral supplements, and exer-cise to maintain a healthy weight andavoid regaining the excess pounds.” ❖

For Obese Teens, Surgery Is the Last ResortWhile such operations are up, they’re not for all youths

E

“If the child does not changebehaviors, then the expectedweight loss may not occur or,with time, could be regained.”

—Ronald Williams, M.D., director ofPenn State Children’s Hospital

Multidisciplinary Weight Loss Program

Yale University School of Medicine. Butdoctors have seen a “significant increase”in flat heads in the past decade, says a2003 article Persing wrote in Pediatrics.

“It’s very important for infants to getsome tummy time when they are awakeand supervised,” says John Kattwinkel,M.D., chairman of the AAP Task Force

on SIDS and a pediatrics professor at theUniversity of Virginia School of Medicine.

To avoid a flat head, Persing andKattwinkel offer these tips:■ Parents should still place babies on

their backs for sleep.■ When babies are awake, put them on

their tummies for a while. This easespressure on the back of the head andhelps babies build shoulder and neckstrength. “This time must be super-vised, 100 percent of the time,” Persing says. “Don’t even run to the bathroom and leave an infant on the tummy.”

■ Relieve pressure on the back of thehead when you lay an infant down for sleep “by very gently turning theirhead 45 degrees to the left one night,then 45 degrees to the right the nextnight,” says Persing.

■ Change the crib’s position a few timesa week. As your child looks around theroom, the head will be in a new posi-tion because of that change.

■ Don’t overuse car seats when the childis not in a car. When in a car, move the car seat often from one side to the other.

■ If your child develops a flat spot on the head, see your doctor. Such flatspots usually form on the back or side of the head. ❖

Safety is your top concern for your child.Just as you put your infant in a car seat,you may think that putting your child ina baby walker is safe, too.

“Safety is a misperception,” says pediatric emergency physician JosephWright, M.D., a member of the AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committeeon Injury, Poison and ViolencePrevention. The AAP terms baby walkersdangerous and says you should throwthem out. “Even when parents are super-vising a child, he or she can move awalker at 3 feet per second,” he warns.

An estimated 4,360 children wereinjured due to baby walkers in 2004,according to the U.S. Consumer ProductSafety Commission. Walkers can causechildren to:■ Roll down stairs, causing head injuries

and even death. This is the mostcommon way kids get hurt in walkers.

■ Get burned. Children in a walker may

be able to reach a hot cup of coffee on a table or a pot on the stove.

■ Drown. A child can roll into a pool orfall into a bathtub or toilet.

■ Be poisoned. A child may be able toreach poisonous items you thoughtwere out of reach.

■ Pinch fingers or toes. A child’s tinydigits can get caught between thewalker and furniture.“Parents should avoid all mobile

walkers,” Wright says. For safety’s sake,also make sure there are no baby walkersanywhere your child spends time.

Walkers also slow development, Wright says. “Motor development isdelayed compared with infants who are not placed in walkers.”

The AAP suggests you use a stationaryjumping device instead. “Nonmobilejumping devices are safer and can pro-vide a level of freedom for parents,” Wright says. Such devices don’t have

wheels; instead, they have seats thatrotate and bounce.

Playpens are safe for children learningto sit, crawl, and walk. High chairs aregreat for older children, who can safelyplay with toys on a tray. ❖

Toss Your Baby Walker, Pediatricians SayChildren can roll themselves into danger

Penn State Children’s Hospital, www.pennstatechildrens.com 7

Playpens are safe for children learning to

sit, crawl, and walk.

Cub Chat is a complimentaryquarterly newsletter produced bythe Office of Strategic Services at

Penn State Children’s Hospital.

For questions or additional copies,

please call (717) 531-8606.

www.pennstatechildrens.com

A. Craig Hillemeier, M.D.Medical Director and Chairman

CHI-3227-06

Articles in this newsletter are written by professional journalists or physicians who strive to present reliable, up-to-date information. But no publication can replace the care and advice of medical professionals,and readers are cautioned to seek such help for personal problems. ©2006 Health Ink Communications, 780 Township Line Road, Yardley, PA 19067, (267) 685-2800. Some images in this publication may beprovided by ©2006 PhotoDisc, Inc. All models used for illustrative purposes only. Some illustrations in this publication may be provided by ©2006 The Staywell Company; all rights reserved. (106)

eaching future doctors how to provide child-friendly andfamily-centered care is as muchan art as it is a science. While

few in number, children’s hospitalstrain almost one-third of our nation’spediatricians and half of all pediatricspecialists, such as neurologists or cardi-ologists. If you have children, they’veprobably been cared for by a pediatri-cian or a family practice physician whotrained at a children’s hospital at somepoint in his or her career.

Because children’s hospitals often takecare of children with very serious andcomplex conditions, such as cancer,

cystic fibrosis, or heart transplants, theymust provide the most technologicallyadvanced care available. Doctors intraining at children’s hospitals get specialized education and unique experi-ence that no other hospital can provide.

But teaching great physicians takestime and money. While Medicare paysfor training physicians in adult hospi-tals, children’s hospitals don’t qualifyfor this funding because they don’t treatadult patients. That’s why, in 1999, the National Association of Children’sHospitals (NACH) successfully lobbiedCongress to create the Children’sHospitals Graduate Medical Educationpayment program. This program pro-vides federal funding to nearly 60 chil-dren’s hospitals that train physiciansand ensures children’s hospitals can continue to provide quality care whilethey train the next generation of healers.

However, NACH and children’s hos-pitals must appeal to Congress for this

funding each year.Ask your chil-dren’s hospitalhow you can helpmake sure chil-dren’s hospitalsget the moneythey need to trainthe doctors whocare for children.

Children’s hospitals also train nurses,occupational therapists, social workers,dentists, and other health care profes-sionals. By receiving professional train-ing in a children’s hospital, our nation’sfuture health care professionals gain anappreciation for the specialized needs ofchildren and develop the skills and com-passion needed to care for families. ❖

TTeaching the Next Generation of Healers

To Learn More

To learn more about the importance ofgraduate medical education to chil-dren’s health and children’s hospitals,visit www.childrenshospitals.net.

N A C H R INational Association of Children’sHospitals and Related Institutionswww.childrenshospitals.net