PREFACE - reptile conservation · PREFACE The article “Morphological characterization of the...

Transcript of PREFACE - reptile conservation · PREFACE The article “Morphological characterization of the...

PREFACE

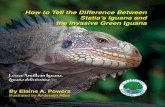

The article “Morphological characterization of the common iguana Iguana iguana (Linnaeus, 1758), of the Lesser Antillean iguana, Iguana delicatissima, Laurenti, 1768 and of their hybrids” by Michel Breuil was originally published in the Bulletin de la Société herpétologique de France, (2013) 147:309–346 in French. The document details the impact and significance of the invasive Iguana iguana on the populations of Iguana delicatissima in the Lesser Antilles.

To support the dissemination of the document to a broader audience for the purpose of awareness, the International Reptile Conservation Foundation (IRCF), non-profit 501(c)(3), has translated the document into English. While best efforts have been made in the translation, no warranties or representations are made with respect to accuracy of the translation. The IRCF thanks Tri Luu for his assistance, time and efforts in translating the original document.

The IRCF expresses its gratitude to the following donors for making this effort possible: 480 Pythons, Aaron Rezek, Adam Landry, Adam Meth, Adrian Ramos, Amanda Rose, Arnold Bantug, Atinat Boonkure, Ashtyn Rance, Beardorama Exotics, Chris Murray, Chris Pellecchia, Christopher McCoy, Jr, Domenic Curcio, Elaine Fournier, Elana Golding Erik & Renata Carlseen, ExotiCare Inc., Frank Coseglia, Frederic Burton, Grant Garton, Gregory Gontowski, Ian Schneider, Jason Juchems, Jason Rogers, Jeremiah Mills, Jill Jollay, John & Sandra Binns, Juliann Hoag, Julie Morningstar, Just Plain Wild Exotics, Karen’s Closet, Ken Foose, Kevin Romero, Kim Cadwallader, Kirsten Lewis, Kisha Jones, Kristen Richards, Lam Do, Littlefoot Animal Refuge, Lynda Bagley, Lynette Huffstedtler, Matthew Krzemienski, Megan Harrison-Moore, Michael Joseph Nesbit, Michelle Cutler, Nancy Harker, Neil England, Nick Chandanais, Nicole Pesek, Patrick Burian, Peggy Mundy, PETOWN L.L.C., Rebekah Gletner, Reversal, Richard Luna, Scales Exotic Creatures, Tri Luu, Ty Park, Warayot Nanakornpanom, Weiyi Lu, Wildlife Discovery Center (City of Lake Forest Parks and Recreation Lake Forest, Ill.), William Bradley, William Stewart, and Zoo Mom Science.

The original document can be found here:

https://www.researchgate.net/prof i le/Michel_Breui l2/publ icat ion/276284428_66._BREUIL_M._2013_-_Caractrisation_morphologique_de_liguane_commun_Iguana_iguana_(Linnaeus_1758)_de_liguane_des_Petites_Antilles_Iguana_delicatissima_Laurenti_1768_et_de_leurs_hybrides._Bull._Soc._Herptol._Fr._147__309-346/links/5555caf508ae6943a871f1f0.pdf

The IRCF expresses its gratitude and appreciation to Michel Breuil for his work and permission to use this document to help develop awareness and support in the efforts to eliminate the hybridization of Iguana delicatissima.

John Binns, CEOInternational Reptile Conservation Foundation

Bull. Soc. Herp. Fr. (2013) 147 : 309-346

Morphological characterization of the common iguana

Iguana iguana (Linnaeus, 1758), of the Lesser Antillean Iguana

Iguana delicatissima Laurenti, 1768 and of their hybrids

by

Michel BREUIL

Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle

Département de Systématique et d’Évolution

CP 30 (Reptiles et Amphibiens)

57, rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris cedex 05

Association Le Gaïac-GECIPAG, La Chaise

97110 Sainte-Rose

Réserve Naturelle de Saint-Barthélemy

Association Grenat, BP 683, Gustavia

97098 Saint-Barthélemy cedex

Summary – Morphological characterization of the common iguana Iguana iguana (Linnaeus,1758), of the Lesser Antillean iguana Iguana delicatissima Laurenti, 1768 and of their hybrids. French West Indies are inhabited by two Iguana species, the Lesser Antillean Iguana (Iguana delicatissima) and the common iguana (Iguana iguana). Historical and morphological data show that the common iguana came to Les Saintes in the middle of the nineteenth century during the exchange of convicts between the prisons of French Guyana and the penitentiary in Les Saintes. Then this species was introduced voluntarily to Basse-Terre in the late 1950’s and to Martinique in the 60’s. It was then introduced in Saint Martin. In Les Saintes and Grande-Terre, the arrival of common iguanas has lead to hybridization between the two species and the elimination of the Lesser Antillean Iguana. In Basse-Terre, all I. delicatissima populations are invaded by common iguanas and their hybrids. Moreover, common iguanas escaped from captivity, and invaded Saint Martin in early 2000 and arrived to Saint Barthélemy; few years later hybridization started. The two species differ from each other by

Page 1

more than 15 characteristics, most of them were unnoticed before the present study. The common iguana from Guadeloupe and Martinique (Iguana iguana iguana) differs also from iguanas found in Central America (Iguana iguana rhinolopha) and from those of the islands of Saint Lucia and Saba whose morphological characteristics are described for the first time. The morphology of the hybrids is described. These hybrids are morphologically very diversified and clearly show that F1 individuals are fertile, leading to introgression and progressive extinction of delicatissima.

Keywords: Iguana delicatissima, Iguana iguana, Iguana iguana rhinolopha, hybridization, morphology,

Guadeloupe, Martinique, St Martin, St Bart, St Lucia, Saba.

I. INTRODUCTION

The two species of the genus Iguana (Laurenti, 1768) live in the French Antilles. The Lesser Antillean iguana, Iguana delicatissima, (Laurenti, 1768) endemic to the Lesser Antilles, Anguilla in the north and Martinique in the south and the common iguana Iguana iguana (Linnaeus 1758) present in Guadeloupe (Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, Les Saintes), Martinique, Saint Martin, Saint Barthelemy (Breuil 2002 Breuil et al. 2010a, 2011a, b), Anguilla, Saba, Montserrat and Saint Lucia (Henderson & Breuil 2012). While the origin of common iguanas of Martinique is well identified from introductions made from Saintes in the ‘60s (Breuil 2009), the situation is less clear for Guadeloupe. Lazell (1973), based on the ecological separation or rather the geographical separation of the two species to Saintes (Guadeloupe) and the terms of their morphological variations, considered the common iguana was a natural inhabitant of the Lesser Antilles and that there was no competition between the two species, as other authors have suggested (reviewed in Breuil 2002). Moreover, according to this author, man would in no way responsible for its distribution in the Lesser Antilles. The studies I conducted since 1987 show that the situation is different. Recall that the Lesser Antillean iguana is a species that was first classified as vulnerable by the IUCN (Day et al. 2000) and it is now considered endangered (Breuil et al. 2010b).

II. HISTORY OF RESEARCH OF SPECIFIC CRITERIA IN THE GENUS IGUANA

Linnaeus (1758) described Lacerta iguana but its diagnosis is too vague to differentiate the two currently recognized species in the genus. He cited figures Seba (1734: 95.1, 95.2, 96.4, 97.3, 98.4) to characterize the common iguana or green iguana. All these figures correspond to the taxon now considered as Iguana iguana (Breuil 2002). Moreover, it suggests, among others, the figure from Sloane (1725) as also representing this species, but this figure is only a reproduction from Du Tertre (1667) corresponding to Iguana delicatissima as shown among other the united tail, lack of subtympanic plate and thorns on the underside of the dewlap (Breuil 2002). Laurenti (1768) described two species of iguana (Iguana delicatissima and Iguana tuberculata) based on plates in the office of natural history of Seba (1734) and the existence of individuals observed in Austria in the collections Count Thurn (Breuil 2002) but disappeared today (Pasachnick et al. 2006). His Latin description allows the identification of the two species. As diagnostic characteristics, Laurenti said the absence of tubercles on the neck in delicatissima and their presence in the common iguana he called, in reference to that characteristic, Iguana tuberculata. In addition, he also noted the flathead of Iguana tuberculata and tuberculous bumps on the back of the head in Iguana delicatissima. If this description is to enable the

Page 2

separation unambiguously of the two species, the quoted figures of Seba however, on which it is to rest in part, is wrong. All mentioned figures by Laurenti (95.1, 95.2, 96.4, 96.5, 97.3, 98.4) are assigned to Iguana delicatissima and none of them is assigned to I. tuberculata, which corresponds to an inversion between the diagnosis and iconography rather than a determination error. Duméril and Bibron (1837) indicated that only 96.5 figure from Seba matches I. delicatissima. The iguana in Figure 96.5 shows no nuchal tubercles, but has a row of sub-labial isodiametric scales and 12 gular spines, a combination of characters that suggests a hybrid (Breuil 2002) has been faithfully drawn. Thus, the descriptions of Linnaeus (1758), of Laurenti (1768) and that of Lacépède (1788) do not correspond to homogeneous groups. If we exclude the error of referring to the figures, the description given by Laurenti of I. delicatissima, based on specimens seen in the collections of Count Thurn is a perfectly diagnosis.

Cuvier (1816) based on an old engraving (Fig. 1) from the early seventeenth century (Besler 1616) and republished by Lochner and Lochner (1716) described the naked necked Iguana under the name Iguana delicatissima Laur. “Looks like the ordinary [iguana], especially by the dorsal spines; but does not have the large plate to the corner of the jaw, or the scattered tubercles on the sides of the neck. The top of the skull is topped with curved plates, the dewlap is poor and without perforations. Laurenti says the Indies.” The review of the reference etching (Fig. 1), but also the image from the Besler museum in the edition of 1616 where this animal is drawn from a different angle, show that this description applies to a rock iguana (Cyclura),

Figure 1: Besler’s (1616) Plate I republished by Lochner & Lochner (1716) under N° XIII and cited by Cuvier (1816) as “L’iguane à col nu. Besler. Mus. tab. XIII. fig. 3. Ig. delicatissima. Laur.” and by Cuvier (1829) as “L’iguane à col nu. (Ig. nudicollis Cuv.) Besler. Mus. tab. XIII. fig. 3. Ig. delicatissima.Laur”.

Page 3

not to Iguana delicatissima as indicated by the curved and oval scales in the corner of the mouth and the absence of gular spines. Moreover, Cuvier wrote of the horned iguana of Santo Domingo (Cyclura) “not unlike the ordinary iguana [common iguana] and even the previous [Lesser Antillean iguana]”. Cuvier (1829) took over the preceding description but had completed it by adding the Latin name of Iguana nudicollis “... bulging sclerosis, tuberculosis occiput; dewlap is poor and has few teeth, and only forward. Laurenti says the Indies, but this is a mistake, as we have received from Brazil and Guadeloupe.” Between the two editions of the works of Cuvier, 1816 and 1829, Le Règne animal, the MNHN received I. delicatissima sent by Félix Louis L’Herminier on a boat from Brazil across the Atlantic (Breuil 2002). Cuvier (1829) has characterized the dewlap, which was not fully visible in the figure which he used to describe his naked necked iguana. Thus the first description of Cuvier (1816) of I. delicatissima Laur. which he calls “naked neck Iguana” applies to a Cyclura and the second refers to the same figure to which he adds copies of I. delicatissima from Guadeloupe sent by Félix Louis L’Herminier (Breuil 2002). Between the two editions of the Règne animal, Merrem (1820) proposed Iguana nudicollis as an alternate name for Iguana delicatissima. Cuvier (1816, 1829) considered that only the figures from Seba (1734) of 95.1, 97.3 and 98.1 correspond to Iguana tuberculate Laur. and hence its reference series contains only that species; these figures from Seba therefore illustrate the syntypes Lacerta iguana of Linnaeus.

Duméril and Bibron (1837) gave a good description of I. delicatissima they named naked necked iguana (Iguana nudicollis), echoing the name of Cuvier probably to avoid giving a name that was applied to two species: “The dorsal crest is proportionately less; plates that are the top of the skull are much tuberculosis, and grouped such that they are formed two projections, one right, one left; under the ear there are no large circular dander; the sides of the legs submandibular, instead of offering a paved with hexagonal scales, each having a single longitudinal row of eight or nine scutes thick, convex that, although actually having several sides, affecting a circular shape; this row is parallel to that of lip plates which it is separated only by one or two series of small scales; the lower part of the baleen is rounded, and its front edge presents at most 8 or 9 serrations. As for the color mode, it looks easier than the iguana tuberculosis; because all the subjects that we found in the case to examine, gave us a uniform bluish green tint on all the upper parts of the body; while the lower differed in that by a lighter color. One individual has shown marked his shoulder a yellow stripe as in the tubercular Iguana.” Following the approach of Linnaeus (1758), Duméril and Bibron (1837) removed the Seba 96.5 figure from their description of the tuberculosis iguana and attributed their naked necked iguana. However, this choice leads to inconsistency as the number of gular spines of 12 on the figure of Seba (Breuil 2002) and becomes 8-9 in their description while this number is less on Iguana delicatissima that they have observed and that are still present in the MNHN collections. The bluish-green color is an optical effect due to the solubilization of yellow-orange carotenoid pigments in alcohol and interference of white light on the scales producing a blue color while physical, superimposed chemical pigments gives the green color on the living. The blue color also appears during moulting.

Wiegmann (1834) described another iguana species native to Mexico under the name Iguana rhinolopha which differs from the Iguana tuberculosis by the presence of little horns on the snout and a lower number of dorsal spines that are also larger (Fig. 2). Subsequently, this species has been recognized by Duméril and Bibron (1837). Boulenger (1885) then considered I. rhinolopha as a subspecies of I. tuberculata which differs only by the presence of two or three tapered and flexible scales back the nostrils. These scales are more pronounced among older males than in females and in the young, these scales are not always visible. According Boulenger, there would be a gradual transition from the tuberculata form to the rhinolopha form. The specimens he used for his diagnosis of tuberculata came from South America, Central America and the Caribbean. The number of spines mentioned by Duméril and Bibron to distinguish rhinolopha from tuberculata was deemed not critical to separate these two species. However, we note that the source of

Page 4

iguanas used by Boulenger covers much of Central America and the island of Saint Lucia. Boulenger also notes that the Iguana tuberculata with conical scales on the snout have the largest number of dorsal spines while Iguana rhinolopha in whom nasal horns are the least developed have considerably less.

Dunn (1934) took over the Boulenger characteristic (nasal flake form of horns) to distinguish rhinolopha form of iguana, and he left the label of Laurenti to resume that of Linnaeus but failed to justify his choice. According to this author, there is a species with two subspecies on the continent. Iguana iguana iguana dwell in Panama and the Atlantic coast of Costa Rica and Iguana iguana rhinolopha would be present in Nicaragua and the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Dunn recognizes as the distinguishing features between Iguana delicatissima and Iguana iguana as the presence of a large subtympanic scale in iguana and its absence in delicatissima, and the presence of a row of large sublabial scales in delicatissima and relatively uniform scales in iguana.

Following the study and measurements of 139 I. iguana in the Caribbean, Central and South America and 29 I. delicatissima, Lazell (1973) rejected the differences noted by previous authors to characterize Iguana iguana iguana, I. i. rhinolopha and Iguana delicatissima and retained only the presence of the big subtympanic plate as constant characteristic differentiating the two species. In addition, this author stated that there is a complete ecological separation between the two species in the archipelago of Les Saintes and that in no case there might have been competition and elimination of the Lesser Antillean iguana by common iguana, as had been suggested for example by Underwood in 1962. Moreover, based solely on the presence of nasal horns and their absence in some iguanas in the range of rhinolopha and their presence both in Central America and the West Indies from Saint Lucia to Grenada, Lazell (1973) rejected the subspecies rhinolopha. However, although the nasal horns iguanas are present in South America and the Lesser Antilles and absent

Figure 2: Iguana iguana rhinolopha from Saint-Martin (A=Male, B=female). The nasal horns, the very large subtympanicscale, the numerous large nuchal tubercles, the body colour, the gular spikes (shape and number) and the colour of the eye distinguish these iguanas from those of St. Lucia.

A B

Page 5

in some Central American iguanas, they do not all have the same morphology. In addition, there are other morphological characteristics that differentiate Central American iguanas from South America iguanas and common iguanas endemic to the Lesser Antilles.

To clarify the debate, I propose for practical reasons that rely on genetic data Malone and Davis (2004) and morphological differences described in this work, which are not confined to the absence or presence nasal horns to reconsider the proposal from Dunn (1934) recognizing the two subspecies:

■ Iguanas of northern South America: Iguana iguana iguana;

■ Iguanas of Central America: Iguana iguana rhinolopha.

Van Denburgh (1898) considered that the iguanas of Mexico belonged to the subspecies Iguana iguana (sic) rhinolopha. Smith and Taylor (1950) have followed this opinion endorsing the earlier proposal by the name Iguana iguana rhinolopha Wiegmann.

For island iguanas and endemic to Saint Lucia, Saba and Montserrat, it would be better to consider them as different lines as shown by the genetic data of Malone and Davis (2004) though the taxonomic level remains unclear (Vuillaume et al. in preparation) which should not be confused with invasive iguanas. This opinion is shared among others by Daltry (2009) and Morton (2009). To take account of morphological features of the endemic iguanas from Saint Lucia and Saba and differentiate from common iguanas, particular morphological characteristics of these island iguanas are presented and interpreted in the light of knowledge about the origin of common iguanas from Guadeloupe and the phenomenon of hybridization (Breuil 2002. Breuil et al 2010A)

III. HISTORY OF THE KNOWLEDGE OF THE SYSTEMATIC OF IGUANA IN THE FRENCH WEST INDIES

Duméril and Bibron (1837) cited the presence of the common iguana as the Iguana tuberculata (Laurenti 1768) in Martinique based on individuals sent by Plée in 1821. The catalog Plée (MS 71 III) kept at the Library of the National Museum of Natural History (Breuil 2002) states: “individual of American iguana more known in Martinique under the green lizard name”. The MS 71 IV mentions “an iguana Spanish Trinity [Trinidad] stuffed (Lacerta iguana) over 5 feet in length and in perfect condition. Another individual from the ordinary iguana of the Trinity but is a much less considerable size.” These three individuals are present in the national collections under the respective numbers MNHN 7481, 7482, 7484 and therefore did not come from Martinique as indicated in the catalogs. Obviously Plée did not differentiate between the two species.

The first common iguana mentioned in the Guadeloupean archipelago was in l’îlet à Cabrit (Saintes) by Dunn (1934). Subsequently, this species has been reported from Terre-de-Haut Les Saintes in 1962 and in 1964 in the Pigeon Islands off the Caribbean coast of Basse-Terre by Lazell (1973). However, in the ‘50s, Underwood (1962) has observed Iguana delicatissima in these islets. Observing Underwood is perfectly reliable, common iguanas from Saintes were released in the south of Basse-Terre in the late ‘50s and gradually replaced the Lesser Antillean iguana (Breuil et al. 2010a).

Page 6

Surveys carried out in Saintes ending in 1992, at the request of the National Park of Guadeloupe, led to the proposal of a competition and hybridization between the two species of iguanas in these islands (Breuil et al. 1994; Breuil 2002). This hypothesis was based partly on the replacement of I. delicatissima by I. iguana in Terre-de-Bas and in the eastern part of Terre-de-Haut and secondly, the presence of individuals with intermediate phenotypes between the two species. Thereafter, surveys conducted on the Basse-Terre have shown, next to pure populations of I. delicatissima, the existence of populations where both parental species coexisted with individuals with intermediate phenotypes (Breuil et al. 1994). The morphological and genetic analyzes of the iguanas in these mixed populations have confirmed the reality of the hybridization (Day & Thorpe 1996). This work was based on the sequencing of the cytochrome c gene differentiating perfectly I. delicatissima from I. iguana by some 10% of substitutions and the existence of individuals with mitochondrial genome of a species associated with the phenotype of the other species or to an intermediate phenotype. However, the original data of this study have not been published, which led to the rejection of hybridization and competition as the main threat to the Lesser Antillean iguana by Lorvelec and Pavis (1999). Genetic differentiation between the two species was later confirmed by Malone et al. (2000) on another mitochondrial sequence (ND4-NatR-Leu). These authors showed that all studied I. delicatissima (Dominica, Saint Eustache, Anguilla) have the same mitochondrial haplotype and the divergence with I. iguana is about 10%, confirming previously published findings on the differentiation of two species.

Following the work Lazell (1973) performed in the ‘60s on the distribution and morphology of the two species, the only difference between these taxa recognized was the presence of a subtympanic plate whose size is at least 80% of the largest diameter of the eardrum. The Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) has a series of 20 individuals captured in the Saintes by Noble in 1914. The iguana MCZ 10969 was determined to be Iguana delicatissima by Lazell (1973) and poses a problem. The presence of nuchal tubercles, the number and shape of gular spines, subtympanic plate of small size, the characteristic sub-labial scales and the back of the skull indicate that this individual is a hybrid iguana (Fig. 3).

I determined from photographs by MCZ the 17 iguanas remaining in the series, all considered in the online catalog as I. delicatissima, with the exception of two individuals from l’îlet à Cabrit, labeled I. iguana. At that time, the Saintes (probably Terre-de-Haut) were inhabited by I. iguana (MCZ 10626, 10968, 10973, 10976, 10977, 10978, 10979, 10980, 10981, 10982, 10983, 10984), I. delicatissima (MCZ 10975) and hybrids (MCZ 10969, 10972). The only morphologically pure I. delicatissima is that illustrated by Dunn (1934) whose skull was mounted thereafter. This skull has the characteristics exhibited by Conrad and Norell (2010). According to Dunn (1934), l’îlet à Cabrit was inhabited in the early twentieth century by I. iguana. Both copies (MCZ 10962-63) from this islet are among the many Iguana iguana ill identified in the catalog of MCZ, but correctly identified by this author. However, the specimen MCZ 10963, a newborn could be introgressed. These data suggest than I. delicatissima seemed already scarce in Terre-de-Haut from the beginning of the twentieth century and the common iguana was already the dominant species at least in part of the island as evidenced by the number of individuals collected. However, it is surprising that Dunn did then mentioned I. delicatissima in Terre-de-Haut (MCZ 10975) whereas most individuals in this series are I. iguana from this island that has obviously not been studied but which were recorded incorrectly in the catalog as I. delicatissima.

Comparison of common iguanas present in Saintes with iguanas from Guyana kept at the Natural History Museum has no evidence of morphological differences between specimens of these two origins. The common Iguanas from Saintes do not present characteristics that might suggest an endemic lineage like those in Saint Lucia, Montserrat and Saba (Malone & Davis 2004). Historical data shows that the common iguana has

Page 7

subsequently been introduced in southern Basse-Terre in the late ‘50s (Breuil et al. 2010a) and from there invaded the island and rest of the Guadeloupean archipelago, except for the moment, the Désirade and islands of Petite Terre. The morphological kinship of common iguanas from Saintes with iguanas from Guyana and the lack of genetic differentiation (Vuillaume et al. In preparation) argue for a recent transportation by man. In 1852, the old ort Josephine, located on the islet in Cabrit became a penitentiary until 1905. The Fort Napoleon built on Terre-de-Haut was completed in 1867, it was later used as a prison until 1902. So, many ships from Guyana including îles du Salut and Saint Laurent du Maroni (two places of the prison) stopped at Saintes for prisoner exchanges and returned to Guyana (Fougère 2010). Common Iguanas have been transported, voluntarily or involuntarily, from Guyana on these occasions and found themselves free on Saintes, including the l’îlet à Cabrit and Terre-de-Haut. It is also contemplated that I. delicatissima from Saintes were distributed through the same channel to South America. In August 2000, following numerous outbreaks of common iguana in a garden of the house where I lodged in the south of Basse-Terre, two infants were found in my luggage and could have been transported to, without my knowledge, another island. This observation clearly shows how easily young iguanas are potential stowaways. Moreover, Indians are known to deliberately transport live iguanas during their travels in the Lesser Antilles (Anonyme de Carpentras 1994). The transport of Iguanas of these islands to Venezuela and the Guyana Shield is plausible.

With the request of a National Action Plan in April 2006 by the Ministry of Ecology and Sustainable Development (MEDD), studies on competition and hybridization of iguanas that had been blocked in Guadeloupe resumed

Figure 3: Iguana MCZ R 10969 collected by Noble in 1914 in les Saintes Archipelago. This iguana was illustrated in black and white in the paper by Lazell (1973) who identified it as Iguana delicatissima. The presence of a subtympanic plate smaller than the tympanum, the small number of nuchal tubercles, the 6-7 triangular gular spikes, the arrangement of the sublabial scales and the colour shows that this individual is probably a backcross with a Lesser Antillean iguana.

Page 8

(Breuil 2003). New surveys were undertaken by the Groupe d’Étude et de Conservation de l’Iguane des Petites Antilles en Guadeloupe (GECIPAG). These surveys show the catastrophic situation of the species in the Guadeloupean archipelago (Breuil et al. 2007, Breuil & Ibéné 2008a, b, Breuil et al. 2010a, 2011, pers. obs. In August 2011, 2012). They allowed the observation of many other hybrids and biopsies for genetic studies. There currently are no more pure breeding population of Lesser Antillean iguana in Basse-Terre and the species has disappeared from Saintes and probably Saint Martin and Grand-Terre while Lorvelec et al. (2007) reported, without citing sources, the actual presence of this species in these islands which suggests that there are still viable populations that have nothing to do with the survival of a few isolated individuals (Breuil & Ibéné 2008b).

Moreover, the common iguana has multiplied more and more and, in five years, it has moved to Marie-Galante, Tintamarre and Pinel (Saint Martin), Saint Barthelemy and Saint Lucia not to mention its proliferation on all of the Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Saint-Martin and its expansion in Martinique. The latest populations of I. delicatissima on Basse-Terre known in the mid-90s (Breuil 2002) are all overgrown with common iguana and hybrids. The National Action Plan for safeguarding the Lesser Antillean iguana is associated, at the request of the Ministry, the elimination of the common iguana, invasive species recognized by the Grenelle de l’environnement. The common iguana is one of the most problematic species on DOM (Breuil et al. 2011) but also in Florida (Krysko et al. 2007) and Puerto Rico (Lopez-Torres et al. 2011). Six years after the request of the Ministry, no concrete action has been taken in Guadeloupe to limit its expansion. However, the community of Saint Barthelemy became an Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT) since 1 January 2011 which enjoys autonomy for environmental management has, since April 18, 2011, a territorial order authorizing the “neutralization” of the common iguana and all hybrid forms. Saint Martin is still under the jurisdiction of Guadeloupe and the common iguana is protected there. The common iguanas in Saint Martin are a result of trade and are now mainly from Central America (Breuil 2002). Common Iguanas present at Saint Barthelemy are from Saint Martin and were released by individuals in the island in the mid-2000s (Breuil et al. 2010a) or forward as suggested by phenotypes showing traces of introgression.

The administrative inertia in the French Antilles undermines all backup plans of the Lesser Antillean iguana in the whole of the Caribbean. It is therefore necessary to offer different managers with reliable criteria to differentiate the two species of iguana, their hybrids and endemic insular forms. These criteria can not be limited to the presence or absence of a subtympanic plate as too many people believe the following working Lazell (1973). The ability to recognize from a morphological point of view the invasive species from local species and their hybrids is therefore essential to avoid, considering only a limited number of characters, or even one, as in Parc Zoologique des Mamelles (Guadeloupe) that an individual is determined wrong and used in future breeding programs. Since the National Action Plan has been requested, the numerous surveys carried out by the GECIPAG (Groupe d’Étude et de Conservation de l’Iguane des Petites Antilles en Guadeloupe), L’ASFA (L’Association pour la Sauvegarde et la réhabilitation de la Faune des Antilles), the MNHN (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle ) and UAG (Université Antilles-Guyane) have helped better understand the morphological diversity of the two species and their hybrids in Basse-Terre, Grande -Terre and Saint Barthelemy. The biology studies of populations I’ve carried out in Chancel since 1994 (Breuil 2009) and now with ONCFS (Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage), at Petite Terre and La Désirade with GECIPAG, at Saint Barthelemy with the Natural Reserve, the Alsophis association and the group Iguana delicatissima de Saint-Barthélemy (IDSB) (2011a Breuil, Quellec 2011a, b) led to the capture and characterization of nearly 1,500 iguanas of both species and a growing number of hybrids.

Page 9

The Nature Reserve of Saint Barthelemy has included in its management plan (Réserve naturelle 2008) control of invasive iguana population. Since 2011, a large study of iguanas was conducted at Saint Barthelemy with the support of the Community, of the Nature Reserve, the Alsophis association and the group Iguana delicatissima de Saint-Barthélemy (http://alsophis-Antilles.blogspot.com/p/groupe-idsb.html). It led to the marking 300 I. delicatissima, the capture and neutralization of common and hybrid iguanas, the strengthening of the population of I. delicatissima on l’îlet Fourchu, the translocation of Iguana delicatissima on l’îlet Frégate and rescue a nesting of this species (Quellec 2011a, b, c).

A fundamental difference in the situation of iguanas in Guadeloupe, Martinique and the northern islands (Saint-Martin, Saint-Barthélemy) is the origin of common iguanas. In Guadeloupe and Martinique, the invasive iguanas came from a population in Guyana while in Saint Martin, they are mainly from Central America and belong to a different clade (Malone et al., 2000, Malone & Davis 2004) morphologically identifiable. However, in Fort-de-France (Martinique), iguanas from Central America are becoming more abundant and hybridising with iguanas from South America introduced by Father Pinchon in the ‘60s (Breuil, pers. obs. unpublished, October 2011).

IV. DIAGNOSTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF TWO SPECIES OF THE GENUS IGUANA

The correct identification of indigenous species relative to invasive species is the key to the success of any conservation program (Powell et al. 2011). The characteristics that I propose to differentiate the two species of Iguana and different island iguana (Fig. 4) characters are easy to grasp. They require no steps and are not dependent on sex as are the size of the dorsal spines. They are also determinable from photographs. They were established after studying over 1,500 I. delicatissima currently in pure populations or have been (Saint Barthelemy, Basse-Terre, Désirade, Petite Terre, Martinique, Chancel Dominique) plus numerous photographs published or not of island iguana that I have not visited such as Anguilla and Saint Eustache. The characteristics of the common iguana present in the French Antilles were compared with individuals from the South American continent tabled in National Museum of Natural History and literature data. This choice was dictated by the fact that no iguana from South America, like those seen in the French Antilles, possesses horns on the nose unlike those present in Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent, Grenada and the Grenadines and Central America (Lazell 1973).

Page 10

However, since the beginning of my comments in 1987, the situation has changed very fast. The common iguana was very localized in Basse-Terre in the late ‘70s (Breuil 2002). In 40 years, it has colonized almost all the coast of Basse-Terre and Grande-Terre. In Martinique, common iguanas introduced from Saintes were limited to the Fort Saint-Louis (Fort-de-France) to the mid-90s, then left to conquer the south of Martinique (Breuil, 2009, 2011b). Moreover, in the past ten years it has been observed in Martinique iguanas from Central America who came from individuals escaped or released from captivity. These iguanas are different from common iguanas originating in Guyana, among other things, a size and a higher build, a subtympanic plate proportionally larger, proportionally more dewlap, nasal scales more or less developed in the form of horns, a rather yellow eye and an orange coloring of the body more or less supported in breeding males.

Figure 4: Current and past distributions of the different lineages of Iguana in the Lesser Antillean north of St. Lucia (map drawing from Henderson & Breuil, 2012). Iguanas from St. Vincent, and Grenada Bank are considered as autochthonous Iguana iguana. Islands or part of islands inhabited by I. delicatissima (South to North): Martinique Bank (Ramiers + Chancel), Dominica Bank, Guadeloupe Bank (N, SE, and SW, Basse-Terre), La Désirade and Petite Terre), Saint-Barthélemy + Îlet Fourchu, and Anguilla. Islands where I. delicatissima disappeared (South to North): Les Saintes Bank, Marie-Galante Bank, Guadeloupe Bank (Grande-Terre), Antigua Bank (Antigua, Barbuda), St. Christopher Bank (St. Christopher, Nevis), Îlets Bonhomme and Frégate North St. Barthélemy, and St. Maarten. Islands inhabited by endemic lineages of Iguana iguana.

Page 11

Since 2006, this scenario of invasion by iguanas from Central America takes place in Saint Lucia where such external iguanas, released from captivity, proliferate despite the control measures implemented (Morton 2009 Daltry 2009). Saint Lucia endemic iguanas are characterized by a set of morphological characters never revealed before this work (Fig. 5) that makes them unique and which are presented below. These morphological differences associated with genetic differences revealed by Malone and Davis (2004) show the originality of this clade that is completely different from that of Central America. The presence of “horns” that unfairly linked them in the rhinolopha taxon appears as a convergence especially since these horns have different characteristics.

Saba iguanas are known locally as “Black Iguanas” (Fig. 6). According to Malone and Davis (2004), they belong to the same clade as Montserrat and Venezuela which form the sister group of that of Saint Lucia. The morphological characteristics of Saba iguanas are presented here. I do not have enough data about Montserrat iguanas to perform a morphological description. However, the available information does not differentiate morphologically from those of Saba. Ongoing genetic analysis iguanas of these populations (Fig. 4) will show their relationship and differentiate from the continental common iguanas.

Figure 5: Iguana from St Lucia (Iguana iguana cf. iguana). Adults (A=male, B=female) characterized by a black-ringed body, a small number of nuchal tubercles, a subtympanic plate similar in size to that of the tympanum, nasal horns, a straight dewlap with 7-8 triangular spikes extending into its lower part, and a brown eye.

A B

Figure 6: Black Iguana from Saba (Iguana iguana cf. iguana). Adult males (A, B) characterized by a black body, a high number of prominent nuchal tubercles, a developed subtympanic plate, a pink and black coloration of the subtympanic plate and of the scales of the cheek, a straight black dewlap with 8-9 triangular spikes extending into its lower part, and a dark brown eye.

A B

Page 12

In Saint Martin, common iguanas were held in hotels and a small zoo situated on the Dutch side but also sold (Breuil 2002). These common iguanas, I observed in 1996, have two origins, probably South American from individuals caught in Guadeloupe or in Suriname, and Central American from individuals from the pet trade. Since the early 2000s, the proliferation of a stock of some 120 escapees during a transit at Princess Juliana Airport (Breuil 2002) changed this situation. These Central American iguanas were recaptured and partly displaced by the Nature Foundation of Saint Martin in the Dutch side and received adjustments to compensate the destruction of mangroves in which they lived during the airport extension (Breuil, 2002, Powell & Henderson 2005). Here we see how an initiative that seemed good impacted because those iguanas invaded Saint Martin and arrived in Saint-Barthélemy. The invasive iguana proliferates especially in the mangroves of the Anse Marcel Marina and other points along the coast. Saint-Martin is faced with the presence of iguanas in Central America and South America that are morphologically identifiable. Anguilla is home to iguanas from Guadeloupe that came naturally with Hurricane Luis in 1995. Some 36 common iguanas were transported on a floating raft and other debris that has washed up in east of Anguilla after passing by Antigua and Barbuda (Censky et al. 1998 Breuil 1999, 2002, Hodge et al. 2011). Some iguanas arrived in Anguilla were measured and marked to follow the invasion process (Hodge et al., 2003, 2011). In the southwest of Anguilla, common iguanas present are from the pet trade (Hodge et al. 2003) and are iguanas from Central America. Thus some 100-300 I. delicatissima remaining Anguilla are surrounded by iguana populations of both origins. It is imperative that common iguanas present in Anguilla are neutralized failing which efforts should be made to quickly remove the last delicatissima. Efforts are being made in this direction (Hodge et al. 2011).

Figure 7: (A) Morphological features of the head of Iguana iguana (Fort Saint-Louis, Martinique). 1. Subtympanicplate. 2. Lower sublabial scales forming a mosaic. 3. Flat sub-labial. 4. Dewlap edges forming a right angle. 5. Gular spikes extending into the lower half of the dewlap. 6. Gular spikes > 10. 7.Triangular gular spikes. 8. Top of head flat. 9. Eye chestnut brown. 10. Nuchal tubercles. 11. Body colour greenish grey.

(B) Morphological characterization of the head Iguana delicatissima (Petite Terre, Guadeloupe Island). 1. No subtympanic plate. 2. Sublabial row of scales ± parallel to the labial scales. 3. Rounded scales. 3. Row of oval scales between the labials and sub-labials. 4. Rounded dewlap edge. 5. Gular spikes on the straight upper edge of the dewlap. 6. Gular spikes <7-8. 7. Conical, long and more or less curved gular spikes. 8. Top of head bumpy. 8’. Occipital bumps. 9. Grey eye. 10. Lack of nuchal tubercles. 11. Body colour brownish-grey.

A B

Page 13

Iguana delicatissima probably died at Saint-Martin and the last individual seems to have been observed in 1996 (Breuil 2002). Powell and Henderson (2005) and Powell (2006) have adopted this view and was endorsed during the drafting of the latest version of the red list of IUCN (Breuil et al. 2010b). Lorvelec et al. (2007) then considered. I. delicatissima is always present, but their data is a simple recovery of Breuil (2002). Moreover, the nature reserve management plan for Saint-Martin (Diaz & Cuzange 2009) indicates the presence of hybrid between I. iguana and I. delicatissima. The photographs underlying this statement show that animals considered hybrids are not. This erroneous information was acquired by Legouez (2010) in the National Action Plan for the Iguana of the Lesser Antilles. The characteristics that I propose to identify the two species of iguanas to adulthood (Fig. 7) and hybrids will avoid such errors. Extensive surveys would be required to search for survivors for translocation of I. delicatissima at l’îlet Tintamarre once invasive iguanas are removed from the islet where these common iguanas are always protected.

1. Subtympanic region

■ Iguana iguana iguana: a shell or subtympanic plate big size, slightly domed, whose diameter is clearly greater than the largest diameter of the eardrum. This shell is lined with a black border especially visible on its upper and front sides. The superior and anterior sides of this shell are surrounded by a series of size scales growth going down. Most anterior sometimes reaches two thirds of the height of the subtympanic plate (Fig. 7A).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: subtympanic plate sometimes more than 3 times the height of the eardrum (Fig. 2).

■ I. iguana St. Lucia: subtympanic plate whose height among both males and females is approximately (± 10%) up to the eardrum (Figs 5, 8).

■ I. iguana Saba: tympanic sub plate a little more than twice the height of the ear drum, black and rose more or less dark, sometimes black out (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: absent subtympanic plate replaced in the back and bottom of the oral corners by many small scales milimeters in size arranged in rows more or less longitudinal well visible among the males. The lower sublabial scales does not extend under the eardrum (Fig. 7B). According Lazell (1973), the subtympanic plate is the only character that differentiates the two species. The inclusion of hybrid (Fig. 3) and island endemic populations of Saint Lucia (Figs 5, 8), Montserrat and Saba (Fig. 6) prevented this author from detecting other diagnostic characteristics.

2. Lower sublabial scales

This section below includes three characteristics of the sublabial scales that are more or less interrelated: them against each other and compared to labial scales, their number and size.

■ Iguana iguana iguana: mosaic of flat scales, fairly uniform, from the edge of the lower lip and extending to the upper limit of the dewlap. Scales growing near the subtympanic plate. In the front, the tip of the nose directly above the front edge of the eye, sublabial scales contiguous to labial scales. First three anterior labial scales in contact with the sublabial scales, the following separate sublabial scales by a row of small elongated scales arranged in the spaces left free at the junction between these two rows. This arrangement, with the increased number of scales in the anteroposterior direction, leading to a skew from 30 to 40° from the horizontal boundary between these scales and those of the dewlap (Fig. 7A).

Page 14

■ I. i. rhinolopha: as in I. i. iguana, the obliquity is higher due to the large size of the plate subtympanic especially in males (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: mosaic rather elongated scales and growing, 2 or 3 slightly decreasing diameter scales before subtympanic plate. This arrangement leads to a skew of about 20° (Figs 5, 8).

■ I. iguana Saba: mosaic of elongated scales pale pink circular, dark pink or completely black. Scales before the subtympanic plate arranged in pairs one above the other. Skew is approximately 20-25° (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: a set of sublabial scales curved and roughly isodiametric, forming a row parallel to the labial scales. Number: 7-8, rarely 9, 10 or 11; separated from the labial scales by one or two lines of small scales curved shape rather than oval. In some individuals of Saint Barthelemy, 1-3 earlier labial scales are directly in contact with the sub-labial. In some individuals, from directly above the eye, these isodiametric scales are replaced by curved scales the diameter of which is between half and one third the diameter of the previous scales. When this type of smaller scales present, they are more numerous and correspond to higher values (9, 10, 11). Rows of labial scales and sublabial scales substantially parallel, however, the number of small scales arranged between these two rows, the appearance of a slight skew in some individuals (Fig. 7B).

3. Form and arrangement of sublabial scales

■ Iguana iguana iguana: sublabial scales flat, roughly hexagonal arranged in a mosaic with the banks often marked with a black border (Figure 7A.).

■ Iguana iguana rhinolopha: sublabial scales shape and size variable (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: sublabial scales more elongated than other iguana, flat or slightly convex, juxtaposed or slightly overlapping. For most individuals no black edging on the edge of the scales and when they have, the deposit of pigments is less uniform than other iguana (Figs 5, 8).

■ I. iguana Saba: sub-labial scales elongated, roughly hexagonal black with anterior and posterior more or less pink (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: sublabial scales curved, isodiametric and aligned (Fig 7B.).

4. Shape and size of dewlap

■ Iguana iguana iguana: large dewlap whose straight leading edge carries gular spines. At its lower end, more or less rounded leading edge; front edge and bottom edge of forming a dewlap more or less right angle (Fig. 7A).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: dewlap even greater than I. i iguana and the lower part is often rounded (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: dewlap straight front edge, but in some individuals, top of the straight edge of the dewlap and bottom curved, black in older individuals (Figs 5, 8).

■ I. iguana Saba: dewlap straight leading edge, straight or rounded bottom edge, black in older individuals (Fig. 6).

Page 15

■ Iguana delicatissima: dewlap rectilinear and oblique front edge approximately the upper third bearing the gular spines, the lower two thirds forming a rounded devoid of thorns (Fig 7B.).

5. Location of gular spines

■ Iguana iguana iguana: gular spines on the anterior edge of the dewlap into the lower half (Figure 7A.).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: gular spines on the anterior edge of the dewlap into the lower half (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: gular spines extending in the upper part of the lower half of the dewlap (Figs 5, 8).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: gular spines extending in the upper part of the lower half of the dewlap (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: gular spines on the straight edge of the dewlap, rarely beyond the junction with the rounded edge (Fig 7B.) with the exception of certain individuals of Saint Barthelemy and Basse-Terre.

6. Number of gular spines

There are difficulties to count gular spines. The smallest in the top of the dewlap on the chin does not exceed 2 mm but their position and form generally used to identify them as such and accounted for.

■ Iguana iguana iguana: at least 10 gular spines perfectly identifiable from medium to large (Figure 7A.).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: at least 10 gular spines perfectly identifiable medium to large (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: 7 gular spines of medium to large size and in the upper part of a dewlap or two very small (Figs 5, 8).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: 8-10 gular spines of medium size (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: often less than 6 gular spines of medium to large size (Fig 7B.).

The values given by Lazell (1973) for this characteristic are 7-22 for I. iguana and 4-10 for I. delicatissima. However, according to this author, these values also reflect the difficulty in counting the gular spines. My counts do not overlap those of Lazell. Indeed, the iguana population of Saint Lucia that Lazell considered to be I. iguana is characterized by a number of gular spines of 7. Similarly, some individuals from Saintes considered by Lazell (1973) as I. delicatissima are hybrid (Fig. 3) and therefore Lazell introduced in the variability of each species characteristics of these hybrid and native islanders attached to I. iguana such as Saint Lucia or Saba. Thus, by considering the number of gular spines in delicatissima populations that are not in contact with I. iguana, we do not account for more than 6 spines of medium to large size, unusually 7 or 8 when considering small. The population of Saint Barthelemy and Basse-Terre differ, in some individuals, the presence of spine which the lowermost is sometimes on the rounded top of the dewlap.

7. Form of gular spines

The shape of these thorns changes with age which sometimes makes comparisons difficult.

■ Iguana iguana iguana: gular triangular spines, rather flattened, sometimes fused at the base and sometimes slightly curved hook (Fig 7A.).

Page 16

■ I. i. rhinolopha: gular triangular spines, rather flattened, sometimes fused at the base and sometimes curved hook, often longer in males than in iguana.

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: gular triangular sometimes slightly flat hook thorns, relatively elongated, rather heterogeneous (Figs 5, 8).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: triangular gular spines flat and relatively short (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: more elongated spines gular, more tapered and thinner. Characteristic more marked when the individual is an elderly male. Rather triangular spines in young (Fig. 7B).

8. Head shape

■ Iguana iguana iguana: flat head and elongated. Seen in profile, the eyebrows forming a slight bump from the base of the skull and muzzle are flat (Fig. 7A).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: as in I. i. iguana, but larger cheeks in males (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: rather short head that looks more like that of I. delicatissima, few tubercles on the undeveloped head occipital bumps (Figs 5, 8).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: as in I. i. iguana, perhaps flatter and more elongated (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: occipital crest formed by scales more or less pointed and tuberculosis. Present in both sexes, but particularly developed in males. Seen in profile, three waves: occipital protuberance, eyebrow and nose (Fig 7B.).

Osteological studies (Conrad & Norell 2010) showed that the skull of I.delicatissima is shorter than the skull of I. iguana. In I. iguana, the frontal bone is virtually in the extension of the nasal bone while in I. delicatissima, it plunges with an angle of about 130°.

9. Eye Color

■ Iguana iguana iguana: brown eye (Figure 7A.).

■ I. i. rhinolopha yellow eye, orange-yellow, more or less dark (Fig. 2).

■ I. iguana St. Lucia: dark brown eye (Fig. 5).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: light brown eye (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: more or less dark gray eye (Fig 7B.).

10. Nuchal tubercles

■ Iguana iguana iguana: tubers (conical scales) on the upper neck. Tubers more or less gray green developed and more or less abundant, particularly marked among older males. There is some variability in this characteristic which would require a more precise quantification (Fig. 7A).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: more tubers and significantly more prominent than I. i. iguana, this character is quite variable as its color (Fig. 2).

Page 17

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: few nuchal tubercles of small size green, gray green (Figs 5, 8).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: very prominent tubercles often grouped in lines parallel to the axis of the body, usually white or gray becoming partly in black melanistic individuals (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: nuchal devoid of tubercles (Fig 7B.).

11. Body color in life

■ Iguana iguana iguana: variable color where gray speckled green dominates as well in males than females (Fig 7A.). Vertical stripes more or less pronounced marking the bodies of some individuals while others have a carpet in phenotype (Lazell 1973). Overall color depending on the proportion of the different color scales. The gray-green individuals have scales that color and dark marks on the body or tail rings correspond to the beaches of black scales. Green apple individuals, as youth, have scales that color.

■ I. i. rhinolopha: variable color, but the reproductive males often display an orange-yellow color more or less steady (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: 6 black bands on the trunk even more marked when the individual is older (Figure 5A.). More posterior bands branched dorsal side. Green apple among newborns and young with already visible bands; older individuals gray green between bands.

■ I. iguana Saba: with age, tend to mélanisme more or less pronounced. The black color appears first on the head, then the dewlap, forelegs and hind and finally the body. The presence of carpet patterns are often visible under black coloring. Black spot between the eye and the ear drum in adults. Some entirely black individuals. Labial scales, under lip, subtympanic plate, pink gular spines more or less dark black (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: dimorphism more or less pronounced coloration. Young of both sexes are apple green and become more or less brown with age. Old males dark brown united, more or less gray (Fig. 7B). Females becoming with age, a darker green gradually invaded by brown plates. Green color due to apple green scales and brown ranges due to scales of this color. I. delicatissima has no marks on the body. Older individuals have lost their original green color and are united.

The iguana Saba was observed by Lazell (1973) approximately 800 m altitude in rainforest. Its habitat seems to be essentially the cliffs of the island facing south where the main populations of the island are installed. These iguanas live mainly in the rocks. The island of Saba is often in the clouds and rain and temperatures are relatively cool. I observed in October iguanas coming out of hiding at 5:45 am and bask with the first rays of the sun. In this type of environment, the black color is an adaptation that promotes rapid increase in body temperature.

12. Colour of tail

■ Iguana iguana iguana: ring-tailed black (Fig. 2).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: ring-tailed black (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: ring-tailed black (Figure 5A.).

■ I. iguana Saba: ringed tail with black rings but based in melanisation of the tail (Fig. 6).

Page 18

■ Iguana delicatissima: no ringed tail. It is united and going, with age, from green to brown from the back end (7B).

13. Anatomy of the tail

■ Iguana iguana iguana: autotomy and tail proportionally longer (about 3/4 of the total length) as that of I. delicatissima, autotomisable tail.

■ I. i. rhinolopha: as in I. i. iguana, autotomisable tail.

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: autotomisable tail, no data on the caudal portion.

■ I. iguana Saba: autotomisable tail, no significant data on the caudal portion.

■ Iguana delicatissima: no caudal autonomy, tail accounting for about two-thirds of the caudal length.

I caught hundreds of Lesser Antillean iguanas either by the base or the tip of the tail and I have never seen an iguana this species that left his tail in my hands. L’Anonyme de Carpentras (1994) mentions that the Indians catch iguanas “with one hand by the tail and the other seized their neck.” When they want to eat, they do a good fire and “take the lizard by the tail tip ... it only spin and to raise its tail ... it thus continues to struggle until death.” When a Lesser Antillean iguana is caught by the tail on a branch or in a hole, he tries to move forward by clinging to the substrate to be released; the ground, he turns around to bite. The tail seems less used as a whip for I. delicatissima when the animal is cornered as is very common in I. iguana. In contrast, in I. iguana caudal autotomy is a phenomenon known by the terrarium and is observed in nature when we grabbed the animal by this appendage. A common iguana grasped by the tail leaves it in the mouth of the predator or hunter who tries to catch it. Furthermore, in mangroves, the escape modes between the two species are different. I. iguana usually falls and flees by swimming underwater. This type of behavior is also reported by Jelski in Daszkiewicz and Massary (2008). However, I. delicatissima tends to rise as high as possible in the tree or to reverse and do not plunge despite having good swimming abilities but lower than I. iguana (Breuil 2002) which may be due to a shorter tail.

The caudal autotomy based on the presence of a cleavage plane within the vertebrae. It is interesting to note that land iguanas (Conolophus) and marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus) of Galapagos as well as the genus Brachylophus from Fiji and Tonga have lost their cleavage plane as I. delicatissima (Frost & Etheridge 1989) and are therefore incapable of autotomy. This difference between the two species of the genus Iguana could be explained by the absence of natural predators likely to catch an iguana by the tail. The loss of this nature increase the likelihood of survival compared to its conservation. The Iguana iguana of Saint Lucia, Saba and Montserrat who arrived later in the Lesser Antilles than Iguana delicatissima have a tail that is autotomisable.

14. Length and weight

I. iguana is much bigger and fatter than I. delicatissima. The biggest male delicatissima captured in Guadeloupe weighed 3.150 kg for a size of 141.5 cm. At Sainte Barthelemy, the largest male measured reached 3.740 kg for 41 cm body length and 121.5 cm in total length. Lazell (1973) mentioned an individual collected in Dominica over 5 feet (> 150 cm) and said he observed individuals probably greater in Terre-de-Bas in Saintes. The size and weight of I. delicatissima vary widely in different populations. For example,

Page 19

males of Terre-de-Bas Petite Terre measure 26.5 cm in body length and a weight of 750 g (n = 45), while those of Saint Barthelemy weigh 2030 g and a length of 34.1 cm (n = 34). The 1500 Lesser Antillean iguanas currently equipped with transponders in the French West Indies since 2006 as part of the National Plan of Action (Association le Gaïac-GECIPAG, Réserve Naturelle de Saint-Barthélemy, ONCFS de Martinique) to save this species will bring, in the long term information including longevity and growth of this species. The markings dewlap made in 1997 Chancel (Martinique) and in 2000-01 at Saint Barthelemy show that this species has a life greater than 18 years, but the size and weight achieved in different populations vary widely for same age.

The larger males I. iguana rhinolopha far exceed 7 kg for sizes greater than 1.80 m. Published data are still fragmented for endemic iguanas from Saint Lucia and Saba. The biggest male known to Saint Lucia (Fig. 5) measures 1.60 m weighing more than 5 kg (Morton 2009).

15. Nasal Horns

I deal with this characteristic at the end because of its peculiarities and significance that was granted. The presence of horns was considered one of the only characters identifying the taxon rhinolopha originally described of Mexico (Fig. 2). Following the discovery of the population of Saint Lucia by Bonnecourt (Fig. 8), Duméril and Duméril (1851) and Boulenger (1885) included this island population in this taxon. Lazell rejected this taxon because of the inconsistency of the change in characteristic “horns” and its presence both in Central America, South America and the West Indies south of Saint Lucia.

■ Iguana iguana iguana: no nasal horns (Fig 7A.).

■ I. i. rhinolopha: 2-5 nasal horns flattened at the base in the anteroposterior direction and aligned in the plane of symmetry. The size of these scales varies by age and sex (Fig. 2), are sometimes absent.

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: horns of 2 to 4, often enlarged at the base, located after the rostral scale; in some individuals one or two lateral scales transformed also into little horns (Figs 5, 8).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: no nasal horns (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: no nasal horns (Fig 7B.).

Figure 8: Iguana from St Lucia (Iguana iguana cf. iguana) (MNHN 2362 collected by Bonnecourt in 1850-51) showing the nasal horns, the small subtympanic plate, the 7 gular spikes, and the low number of small nuchal tubercles.

Page 20

Tabl

e I:

Com

paris

on o

f the

phe

noty

pes

from

diff

eren

t Igu

ana

igua

na p

opul

atio

ns

Igua

na i.

igua

na

Sout

h A

mer

ica

(Guy

ana)

Igua

na i.

rhin

olop

ha

Cen

tral

Am

eric

a

Igua

na ig

uana

(Sab

a)

Igua

na ig

uana

(Sai

nt L

ucia

)

1. S

ubty

mpa

nic

regi

on

Sub

tym

pani

c pl

ate

(PS

T) ta

ll 2x

ear

drum

sur

-ro

unde

d by

a b

lack

circ

le

Sub

tym

pani

c pl

ate

larg

e 2.

5 to

3×

eard

rum

su

rrou

nded

by

a bl

ack

circ

le

Sub

tym

pani

c pl

ate

larg

e

2-2.

5x e

ardr

um p

ink

and

blac

k

Sub

tym

pani

que

plat

e th

e si

ze o

f the

ear

drum

± 1

0%

2. P

oste

rior s

ubla

bial

sc

ales

Sca

les

mos

aic

form

ing

a ci

rcul

ar a

rc a

roun

d th

e pl

ate,

or s

cale

siz

e sl

ight

ly

low

er th

an P

ST

Sca

les

mos

aic

form

ing

a ci

rcul

ar a

rc a

roun

d th

e pl

ate,

or s

cale

siz

e sl

ight

ly

low

er th

an P

ST

3-5

pairs

of s

cale

s

pink

and

bla

ck s

ize

com

para

ble

to th

e

subt

ympa

nic

plat

e

2 or

3 s

cale

s of

siz

e

decr

easi

ng fo

rwar

d of

PS

T; n

o cr

own

scal

es a

roun

d th

e P

ST

3. F

orm

of t

he la

bial

sc

ales

and

sub

labi

als

Labi

al s

cale

s an

d su

blab

ial

plat

es ju

xtap

osed

Labi

al s

cale

s an

d su

blab

ial

plat

es ju

xtap

osed

, som

e-tim

es a

way

by

the

size

of

jow

ls

Labi

al s

cale

s an

d su

blab

ial

plat

es ju

xtap

osed

Labi

al s

cale

s an

d su

blab

ial

plat

es s

light

ly o

verla

ppin

g

3 ‘.

Layo

ut o

f lab

ial s

cale

s an

d su

blab

ials

Row

s of

labi

al s

cale

s un

-se

para

ted

from

mos

aic

of

sub-

labi

al b

y sm

all s

cale

s el

onga

ted

over

the

entir

e le

ngth

Row

s of

labi

al s

cale

s un

-se

para

ted

from

mos

aic

of

sub-

labi

al b

y sm

all s

cale

s el

onga

ted

over

the

entir

e le

ngth

Row

s of

labi

al s

cale

s un

-se

para

ted

from

mos

aic

of

sub-

labi

al b

y sm

all s

cale

s el

onga

ted

over

the

entir

e le

ngth

Labi

als

ssep

arat

ed fr

om

subl

abia

ls b

y a

row

of e

lon-

gate

d po

lyhe

dral

sca

les

4. F

orm

of d

ewla

pS

traig

ht le

adin

g ed

ge,

botto

m e

dge

mor

e or

less

st

raig

ht

Dew

lap

larg

er s

ize

ofte

n lo

wer

edg

e ro

und

Stra

ight

lead

ing

edge

, bo

ttom

edg

e m

ore

or le

ss

stra

ight

front

end

± ro

und

5. L

ocat

ion

of g

ular

sp

ines

¾

hig

her

¾ h

ighe

r¾

hig

her

¾ h

ighe

r

6. C

olor

dew

lap

Sam

e co

lor a

s th

e bo

dy,

but s

ome

indi

vidu

als

with

a

porti

on o

f the

bot

tom

bla

ck

Sam

e co

lor a

s th

e bo

dy,

gree

n, o

rang

e, g

ray

Bla

ckB

lack

with

Gre

en

Page 21

Igua

na i.

igua

na

Sout

h A

mer

ica

(Guy

ana)

Igua

na i.

rhin

olop

ha

Cen

tral

Am

eric

a

Igua

na ig

uana

(Sab

a)

Igua

na ig

uana

(Sai

nt L

ucia

)

7. N

umbe

r of g

ular

e sp

ines

med

ium

to h

igh

≥ 10

≥ 10

≤ 9

7

8. F

orm

of g

ular

spi

nes

Flat

, sho

rt an

d

trian

gula

r

Flat

, sho

rt an

d

trian

gula

r

Flat

, sho

rt an

d

trian

gula

r

Flat

, tria

ngul

ar,

hook

9. H

ead

shap

eFl

atFl

at a

nd e

long

ated

Flat

and

elo

ngat

edS

hort

and

rela

tivel

y fla

t

10. C

olou

r of t

he e

ye (i

ris)

Bro

wn

Yello

w o

rang

eG

ray-

brow

nD

ark

brow

n

11. N

ucha

l tub

ercl

es

Abu

ndan

t and

pro

min

ent

Abu

ndan

t and

ver

y pr

om-

inen

t

Abu

ndan

t and

prom

inen

tS

mal

l and

few

12. N

asal

sca

les

No

horn

s

2-4

flat h

orns

,

trian

gula

r and

gene

rally

stra

ight

No

horn

s

Hor

ns s

ectio

n ra

ther

ova

l, of

ten

curv

ed, 2

to 4

in th

e

plan

, 1 o

r 2 s

ide

pairs

sm

all

and

not a

lway

s

pres

ent

13. B

ody

colo

r (ad

ult)

Gra

y, g

reen

± d

ark,

uni

ted,

with

ban

ds, c

arpe

t pat

tern

s

Gre

en, g

ray,

ora

nge

mal

es

rutti

ng

Gra

y gr

een

in a

dults

, som

e-tim

es w

ith fu

ll m

elan

ism

e,

blac

k sp

ot b

etw

een

the

eye

and

the

ear d

rum

Bla

ck b

ands

on

the

body

mor

e m

arke

d w

hen

the

indi

vidu

al is

old

er a

nd m

ale.

G

reen

app

le to

gre

en g

ray

with

age

.

14. C

olor

dor

sal s

pine

sG

reen

gra

y, ±

dar

k G

ener

ally

yel

low

, ora

nge

mal

es in

rut

Ligh

t gra

y-gr

een

to to

tally

bl

ack

Sam

e co

lor a

s th

e bo

dy

gree

n to

gra

y gr

een,

ligh

t or

ange

at t

he e

nd

15. S

ize

dors

al s

pine

sH

igh

Very

hig

h M

ediu

m-h

igh

Very

hig

h

16. O

vera

ll le

ngth

max

imum

adu

lts>

150

> 18

0D

ata

defic

ient

> 15

0

17. W

eigh

t max

imum

ad

ults

> 5k

g>

7 kg

Dat

a de

ficie

nt>

5kg

Page 22

16. Color and size dorsal spines

According Duméril and Bibron (1837), the lower number of spines, the presence of horns and proportionally higher dorsal scales are the only criteria that differentiate Iguana rhinolopha from Iguana iguana.

■ Iguana iguana iguana: green, gray-green, medium (Fig 7A.).

■ I. i. rhinolopha gray green, often orange in breeding males, tall (Fig. 2).

■ Iguana iguana St. Lucia: yellow green, gray, orange adult male, tall (Fig. 5).

■ Iguana iguana Saba: pink, gray, dark gray to black, medium size high (Fig. 6).

■ Iguana delicatissima: bluish gray, lighter or darker, smaller than that of other taxa (Fig 7B.).

Table I summarizes the characteristics of different populations of Iguana iguana.

V. HYBRID PHENOTYPES

All iguanas in populations where I. delicatissima and I. iguana were present were identified based on diagnostic characteristics described above and presumed to be a hybrid based on its phenotype if it has characteristics intermediate between the two parental species and / or a mosaic of characteristics from both parent species. When you consider all hybrid populations and all characteristics, the variety of phenotypes we noted, made me suggest, in 2000 (Breuil 2000, 2002), the possibility that hybrids are fertile and they are at least capable of backcrossing with one of the two parental species. Some individuals have an intermediate phenotype for all characteristics while others are at overall phenotype of a species and a few more or less pronounced than the other characteristics. The first category suggesting that these individuals are F1 hybrid (Fig. 9). The second category is either hybrid F2, F3 or to backcross (backcross) successive (Figs 10, 11). Table II summarizes the diagnostic characteristics of both species and phenotypes supposed hybrids F1. However, due to differences in the phenotypes of both parent species, the way crosses may have an influence on the phenotype of hybrid is not possible to quantify at the moment. Hybrids described match those of Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre and Les Saintes, i.e. at crossings between the Lesser Antillean iguana and common iguana from Guyana. Hybrids of Saint Barthelemy include individuals who come from hybridization between I. delicatissima and iguanas from South America and / or Central America.

1. Subtympanic region: subtympanic plate vs small scales

■ Hybrid F1: subtympanic plate reaching 1-2 times the height of the eardrum. The size of this plate is associated with sexual dimorphism and age (Fig. 9).

■ Post F1 Hybrid: subtympanic plate of the size of that of I. iguana, less than the height of the eardrum, sometimes located slightly forward of plumb eardrum, or small scales as in delicatissima (Figs 10, 11).

Page 23

Tabl

e II:

Com

paris

on o

f the

phe

noty

pes

of Ig

uana

i. ig

uana

, Igu

ana

delic

atis

sim

a an

d th

eir F

1 hy

brid

s.

Igua

na i.

igua

naIg

uana

del

icat

issi

ma

F1 H

ybrid

s

1. S

ubty

mpa

nic

regi

onLa

rge

subt

ympa

niqu

e pl

ate

Man

y m

illim

eter

siz

ed s

cale

s

Sub

tym

pani

c pl

ate

may

be

slig

htly

smal

ler t

han

igua

na s

omet

imes

pl

aced

slig

htly

in fr

ont o

f the

ear

-dr

um

2. P

oste

rior s

ubla

bial

sca

les

Sca

les

form

a m

osai

cS

ubla

bial

sca

les

± fra

ctio

nate

d3

or 4

sub

labi

al s

cale

s po

ster

ior ±

alig

ned

± la

rge

3. F

orm

of t

he la

bial

sca

les

and

subl

abia

lLa

bial

sca

les

and

subl

abia

l flat

Labi

al s

cale

s an

d su

blab

ial c

onve

xLa

bial

sca

les

and

subl

abia

l ±

conv

ex

3 ‘.

Layo

ut o

f lab

ial s

cale

s

and

subl

abia

ls

Row

s of

labi

al s

cale

s in

con

tact

with

th

e su

b-la

bial

Row

of s

ubla

bial

sca

les

±

isod

iam

etric

sep

arat

ed fr

om la

bial

by

sm

all e

long

ated

sca

les

Row

± is

odia

met

ric s

ubla

bial

sca

les

mor

e or

less

sep

arat

ed fr

om la

bial

sc

ales

by

smal

l elo

ngat

ed s

cale

s

4. F

orm

of d

ewla

pS

traig

ht fr

ont e

dge

Stra

ight

lead

ing

edge

in th

e up

per

part,

roun

ded

in th

e lo

wer

par

t

Inte

rmed

iate

, the

sep

arat

ion

betw

een

the

stra

ight

par

t and

the

curv

ed p

art i

s le

ss m

arke

d

5. L

ocat

ion

of g

ular

spi

nes

Upp

er th

ree

quar

ters

Top

quar

ter i

n th

e st

raig

ht p

art,

rare

ly 1

or 2

to th

e ju

nctio

n w

ith th

e ro

unde

d pa

rt

Upp

er h

alf,

rega

rdle

ss o

f the

shap

e of

the

front

edg

e

6. N

umbe

r of g

ular

spi

nes

> 10

<78-

9

7. F

orm

of g

ular

spi

nes

Flat

, sho

rt an

d tri

angu

lar

± C

onic

al a

nd lo

ng

Tria

ngul

ar, m

ore

or le

ss fl

at a

nd

long

8. H

ead

shap

eFl

atH

unch

back

ed±

Hun

chba

cked

9. C

olor

of t

he e

ye (i

ris)

Bro

wn

Gre

yG

rey

brow

n ±

dark

10. T

uber

s nu

caux

Abu

ndan

t and

pro

min

ent

Abs

ent

Few

er a

nd s

mal

ler

11. B

ody

colo

r (ad

ult)

Gra

y, d

ark

gree

n ±,

uni

ted

with

ba

nds,

car

pet p

atte

rns

Bro

wn