Precursor manic behavior in the assessment and treatment of episodic problem behavior for a woman...

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

kristina-k -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

2

Transcript of Precursor manic behavior in the assessment and treatment of episodic problem behavior for a woman...

PRECURSOR MANIC BEHAVIOR IN THE ASSESSMENT ANDTREATMENT OF EPISODIC PROBLEM BEHAVIOR FOR

A WOMAN WITH A DUAL DIAGNOSIS

MARISSA B. ALLEN

MELMARK NEW ENGLAND

AND

JONATHAN C. BAKER, JODI E. NUERNBERGER, AND KRISTINA K. VARGO

SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY–CARBONDALE

A functional analysis examined the relation between consequences that maintained episodicproblem behavior (aggression, property destruction, and elopement) in the presence and absence ofmanic behaviors (MB). Results suggested that the presence ofMBwas correlated with the sensitivityof problem behavior to attention as a reinforcer during a functional analysis and that problembehaviors were maintained by attention. Noncontingent reinforcement was subsequentlyimplemented and demonstrated to be effective in reducing problem behavior during the presenceof manic behaviors.Key words: functional analysis, precursor behavior, dual diagnosis, noncontingent

reinforcement

The problem behavior of individuals withintellectual disabilities (ID) has been demonstrat-ed to be sensitive to social contingencies (Iwataet al., 1994). Although a functional analysis (FA)of behavior is a crucial first step in implementingeffective treatment (Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bau-man, & Richman, 1982/1994), FAs may produceundifferentiated or false-negative results (e.g.,when aggression is maintained by attention, but issensitive to the reinforcement contingency onlywhen a specific motivating operation is present;O’Reilly, 1997). One approach for clarifying FAresults is to extend the analysis to precursorbehaviors, which are behaviors that both precedeand predict problem behaviors (Fahmie &Iwata, 2011). Although researchers have typically

applied FA contingencies to precursor behaviorsso that less intense behaviors are reinforced duringan FA, research also supports the use of precursorsto help determine when to assess problembehaviors that occur infrequently (Fahmie &Iwata, 2011). When FA test conditions fail toevoke problem behavior reliably, the presence ofprecursor behaviors could be used to indicateappropriate times to conduct the FA. That is, ifprecursor behaviors are maintained by the samereinforcer as problem behaviors, the presence ofprecursor behaviors might signal optimal timeswhen test conditions would be likely to evoke andmaintain the problem behavior (Tarbox, Wallace,Tarbox, Landaburu, & Williams, 2004).

The purpose of the current study was twofold.First, we examined the consequences thatmaintained episodic problem behavior and therelation between those consequences and precur-sor manic behavior (MB; e.g., elevated speech).Second, we implemented noncontingent rein-forcement (NCR) to treat the episodic problembehavior (i.e., the problem behavior exhibitedwhen MB was also exhibited).

We thank Nicole Heal, Bud Mace, and Joel Ringdahl fortheir help, guidance, and suggestions with this project. Wealso thank Amanda Buchmeier and Sarah Bocock for theirhelp with data collection.

Correspondence concerning this article should beaddressed to Jonathan C. Baker, Rehabilitation Institute,Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62918(e-mail: [email protected]).

doi: 10.1002/jaba.57

JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS 2013, 46, 685–688 NUMBER 3 (FALL 2013)

685

METHOD

Participant and SettingNelly was a 48-year-old woman with a dual

diagnosis of moderate ID and schizoaffectivedisorder, bipolar type (she received 500 mg ofClozaril and 2,750 mg of Depakote daily); sheresided in a state facility. She was ambulatory,communicated by speaking in three- or four-word sentences, and could follow single-stepinstructions. Nelly’s speech was usually clear, easyto interrupt (i.e., she typically paused betweenwords), and easily understood by her communi-cation partners. She did not experience anychanges in dosages or medications, sleep patterns(averaged 6.5 to 7.5 hr of sleep per night), orhealth throughout the study.Approximately one to six sessions were con-

ducted per day, 1 to 5 days per week, in the dininghall. The session area contained a divider screen (tolimit distractions), table, chairs, and other materialsas needed (see below). Aside from treatment analysisconditions, all sessions were scheduled (i.e., thesession occurred regardless of precursor behaviors).

Response Measurement and InterobserverAgreementNelly’s problem behaviors included property

destruction (throwing or tearing leisure materi-als), elopement (standing up and walking out ofthe session room), and aggression (firmlygrabbing and pulling on the experimenter orcursing). Independent observers used laptopcomputers to score the frequency of problembehavior in continuous 10-s intervals. Twoindependent observers scored problem behaviorsimultaneously but independently during 100%of all FA sessions and 40% of treatment analysissessions. Agreement was defined as two indepen-dent observers scoring the exact same top-ographies and frequencies of problem behaviorin a given 10-s interval. Interobserver agreementwas calculated by dividing the number ofintervals with agreement by the number ofagreements plus disagreements and convertingthe result to a percentage. Mean interobserver

agreement across FA sessions was 98% (range,91% to 100%) and across treatment sessions was99% (range, 99% to 100%).Manic behavior was defined as loud (elevated

above typical conversational), rapid (emitting twoor more word bursts without pausing), anddifficult-to-interrupt speech. All three character-istics needed to be present to count as the presenceofMB. Staff at the facility used paper and pencil torecord whether or not MB occurred hourly acrossthe day. Interobserver agreement was calculatedbetween the primary observer (i.e., first author)and staff on the occurrence of MB. An agreementwas defined as the two independent observersscoring the presence or absence of MB during agiven 1-hr interval before sessions. Staff whoworked directly with Nelly were blind withrespect to the nature of the researcher’s datacollection; the researcher simply informed staffthat she would observe Nelly’s behavior in herhome setting for 1 hr before the sessions becausethese observations would contribute helpfulinformation to the study. The researcher didnot access staff data until after sessions had beencompleted each day. Interobserver agreement onMB was obtained for 75% of the FA sessions and60% of sessions during treatment and was 100%.To obtain treatment integrity data, observers

scored the occurrence of correctly and incorrectlydelivered (a) consequences during 27% of the FAsessions and (b) noncontingent attention during46% of NCR sessions. Mean treatment integritywas 96% (range, 93% to 99%) during FA andNCR sessions.

Functional AnalysisThe FA was conducted using a pairwise

multielement design, in which 5-min controlconditions and test conditions alternated quasir-andomly. Each session was separated by a 2-minbreak. The occurrence of sessions depended onNelly’s schedule (e.g., bathroom, snack, and dailyactivities before sessions varied in duration) andassent (e.g., Nelly asked to leave after one sessionor refused to participate on some days).

686 MARISSA B. ALLEN et al.

Attention. Nelly was seated at a table next tothe experimenter. The experimenter placed abright purple poster on one of the walls visible toNelly and wore a bright purple t-shirt. Due tosafety concerns associated with conductingsessions in the dining room (e.g., access to solidfoods that were choking hazards, trash, utensils),Nelly could not be left alone before sessions.However, pre- and between-session interactionswere kept minimal to avoid abolishing themotivating operation for attention. During thesession, the experimenter delivered a briefstatement (e.g., “I like your shoes”) or placedher hand on Nelly’s shoulder contingent onproblem behavior. These responses were selectedbecause they were similar to what staff had beenobserved to provide in the natural environment.Nelly received noncontingent access to preferredmaterials throughout the session.Control. The experimenter placed a black

poster on one of the walls visible to Nelly andwore a black t-shirt. Nelly received attentionevery 30 s (e.g., the experimenter said, “It is anice day,” or placed her hand on Nelly’s shoulder)and noncontingent access to preferred materials,and the experimenter responded to any inter-actions initiated by Nelly. Problem behaviorsresulted in no programmed consequences.

Treatment AnalysisTreatment was evaluated using an ABAB

reversal design.Baseline. The last three attention sessions of

the FA during which MB was present served asthe initial baseline. During the return to baselinewithin the reversal, sessions were identical to theattention condition of the FA, with the exceptionthat sessions were conducted contingent on theoccurrence of MB.NCR. Procedures were identical to the control

condition of the FA.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONWe compared the results of the FA when MB

was or was not recorded within the previous hour

(Figure 1, top). Nelly engaged in high rates ofproblem behavior across the attention condition(M ¼ 1.2 responses per minute; range, 0.2 to 2.4)when MB were observed before the session (MBphases). Conversely, she engaged in near-zero levelsof problem behavior (M ¼ 0.03 responses perminute; range, 0 to 0.2) during attention sessionswhen MB were absent before the session (no-MBphases). Moreover, she did not engage in problembehavior during the control condition, irrespectiveof whether or not MB preceded the session.Figure 1 (bottom) depicts the results of the

NCR treatment analysis, which was implementedonly when MB was observed prior to sessions.During baseline, Nelly engaged in high levels ofproblem behavior (M ¼ 1.9 responses per min-ute; range, 1.4 to 2.4). After implementation ofNCR, the level of problem behavior dropped tonear zero (M ¼ 0.1 responses per minute; range,0 to 0.4). This pattern of responding (higher levelsin baseline, near-zero levels during treatment) wasreplicated when treatment was subsequentlyremoved and then reinstated.The present study examined the consequences

that maintained episodic problem behavior andthe relation between those consequences and thepresence of MB before sessions. The currentstudy extends research related to clarifying FAresults in its application to MB correlated withproblem behavior. In the presence of MB,problem behavior was sensitive to social contin-gencies and more likely to occur. Research hasshown that it is possible for collateral behavior tocue optimal times to conduct FA sessions forproblem behavior thought to be related to anorganic cause (e.g., O’Reilly, 1997; Tarbox et al.2004 in ref. list.). One limitation to the currentstudy is that precursor behaviors (e.g., MB) werenot included in the FA, so it is not possible to sayif they were also maintained by attention.Fahmie and Iwata (2011) noted that one

missing area of research related to precursorbehavior was on “a precurrent relation, in whichoccurrence of a precursor increased the probabil-ity of reinforcement for a problem” (p. 997).

PRECURSOR MANIC BEHAVIOR 687

They go on to suggest that a precurrent relationmay be in place “if a precurrent response increasesa caregiver’s detection of the problem. Forexample, screaming or crying might serve thispurpose well because they are salient responsesregardless of the caregiver’s location or orientationrelative to the client” (p. 997). It is possible thatNelly’s MB might have functioned in this way.That is, staff may have become more sensitive toNelly’s problem behaviors when she engaged inMB. Future research might further evaluate thepossibility that precursor behaviors can becomepart of a precurrent relation.

REFERENCES

Fahmie, T. A., & Iwata, B. A. (2011). Topographical andfunctional properties of precursors to severe problembehavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 993–997. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-993

Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M., Slifer, K., Bauman, K., &Richman, G. (1994). Toward a functional analysis ofself-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27,197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprintedfrom Analysis and Intervention in DevelopmentalDisabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982)

Iwata, B. A., Pace, G. M., Dorsey, M. F., Zarcone, J. R.,Vollmer, T. R., Smith, R. G., … Willis, K. D. (1994).The functions of self-injurious behavior: An experi-mental-epidemiological analysis. Journal of AppliedBehavior Analysis, 27, 215–240. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-215

O’Reilly, M. F. (1997). Functional analysis of episodic self-injury correlated with recurrent otitis media. Journal ofApplied Behavior Analysis, 30, 165–167. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-165

Tarbox, J., Wallace, M. D., Tarbox, R. S. F., Landaburu, H.J., & Williams, W. L. (2004). Functional analysis andtreatment of low-rate problem behavior in individualswith developmental disabilities. Behavioral Interven-tions, 19, 73–90. doi: 10.1002/bin.158

Received November 14, 2012Final acceptance April 8, 2013Action Editor, Michele Wallace

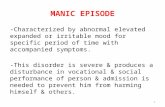

Figure 1. Rate of problem behavior during the functional analysis (top). MB ¼ manic behaviors were observed beforethe session; No MB ¼ manic behaviors were absent before the session. Rate of problem behavior during treatment sessionsfor which manic behaviors were observed before the session (bottom).

688 MARISSA B. ALLEN et al.