POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE - urbancentre.utoronto.ca · Poverty by Postal Code details the dramatic...

Transcript of POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE - urbancentre.utoronto.ca · Poverty by Postal Code details the dramatic...

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

A Report Prepared Jointly byUnited Way of Greater Toronto and

The Canadian Council on Social Development

M6L 1K9 M1K 2J5 M5E 1B3 M6J 2X4 M5E 1W2 M6L 1K9 M2N 1H0 M7G 2N6 M6L 1K9 M1K 2J5 M6L 1K9 M1K 2J5 M5E 1B3 M6J 2X4 M5E 1W2 M6L 1K9 M2N 1H0

K9 M1K 2J5 M5E 1B3 M6J 2X4 M5E 1W2 M6L 1K9 M2N 1H0 M7G 2N6 M6L 1K9 M1K 2J5 M6L 1K9 M1K 2J5 M5E 1B3 M6J 2X4 M5E 1W2 M6L 1K9 M2N 1H0

The Geography of Neighbourhood Poverty l 1981–2001

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

The Geography of Neighbourhood PovertyCity of Toronto, 1981 - 2001

A REPORT PREPARED JOINTLY BY

UNITED WAY OF GREATER TORONTO AND

THE CANADIAN COUNCIL ON SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

APRIL 2004

UNITED WAY OF GREATER TORONTO

Research, Analysis, & Writing:Susan MacDonnell, Research DirectorDon Embuldeniya, Research AnalystFawzia Ratanshi, Research Analyst

CANADIAN COUNCIL ON SOCIAL

DEVELOPMENT

Research & Analysis:John Anderson, Vice-President, ResearchPaul Roberts, Senior Research AssociateKate Rexe, Research Assistant

© United Way of Greater Toronto, 2004National Library of CanadaISBN 0-921669-33-X

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Why worry about poor neighbourhoods? Shouldn’t we con-centrate on helping poor people? Of course, United Way ofGreater Toronto cares deeply about both. We are con-cerned about the profound human cost of poverty on indi-viduals and families who struggle not only to survive, but toparticipate fully as citizens. This report, however, focuses onthe geography of poverty, because neighbourhood povertyhas a devastating human cost and also damages the economicand social vitality of an entire region, affecting the quality oflife for everyone in Toronto.

Healthy neighbourhoods are the hallmark of Toronto’s civicsuccess. Their strength comes from the rich mixture of cul-tures of residents, safe streets, abundant green space, diversi-ty of shops and cultural amenities, and the social infrastruc-ture of community services and programs. All these factorsbring Toronto worldwide recognition as one of the best citiesin the world.

But there are troubling signs that all is not well with ourneighbourhoods. Poverty is rising, and deepening, and theincome disparity between rich and poor is widening.Toronto’s population is growing much faster in the innersuburbs yet there has been no commensurate investment insocial infrastructure.

Poverty by Postal Code details the dramatic increase in thenumber of poor Toronto neighbourhoods. It shows that thecity now has many more concentrated areas of poverty thanit did 20 years ago. This rapid and extensive growth in thenumber of neighbourhoods with a high proportion of fami-lies living in poverty not only undermines their strength - andToronto as a whole - it also makes children, single parents,newcomers and visible minorities particularly vulnerable.

We must emphasize that United Way does not wish to stig-matize neighbourhoods or their residents. Rather, our goal isto highlight the real challenges and multiple barriers facingthese communities to educate, influence, and create a catalyst for collective action.

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

The increase in neighbourhood poverty is especially alarming for two reasons. First,we know that the consequences of living in a poor neighbourhood are significant - andlong-term - for children and youth, for newcomers to our country, for the entire com-munity. Second, poor neighbourhoods can spiral into further decline, cause increasesin crime and abandonment by both residents and businesses. And, shockingly,Toronto is losing ground faster than any other urban centre in Canada.

Poverty by Postal Code was undertaken as part of United Way’s ongoing research intosocial issues, and to help determine its funding priorities. With the assistance of theCanadian Council on Social Development, it was written to provoke governments andcommunities to act. Neighbourhood decline is not inevitable, and investments in com-munities do make an enormous difference. That is the lesson to be learned from suc-cessful neighbourhood revitalization efforts in the United States and Britain. Bothcountries experienced the bitter consequences of neighbourhood-based social andeconomic exclusion; they learned these lessons the hard way - after many of theirurban neighbourhoods had become areas of intense, racialized poverty and urban des-olation. And both countries have seen these neighbourhoods transformed - throughreinvestment and collaboration - into strong, vibrant foundations of healthy cities offer-ing their citizens an improved quality of life and economic opportunities.

United Way of Greater Toronto builds for the future with a history of solid research,thoughtful response, and action. A Decade of Decline, released in 2002, providedToronto with hard evidence of growing poverty and income disparity that occurredduring a period of robust economic growth. Despite the economic recovery of the late1990s, Torontonians were falling behind financially, the gaps between the city’s richand poor had widened significantly, and poverty was increasing in neighbourhoodsoutside the downtown core.

Three months later, United Way launched Strong Neighbourhoods, Healthy City, apilot to help address the lack of social infrastructure in several of the city’s mostunderserved communities. This strategy funds innovative service partnerships in neigh-bourhoods across the inner suburbs, directs more donor dollars to these areas, andstrengthens social service agencies.

Other United Way research has exposed challenges facing our communities. In 2002,our concern about the loss of access to public infrastructure led to the creation of aspecial task force, which published Opening the Doors: Making the Most ofCommunity Space. This report linked adequate community programs and the healthof the city, and called for the preservation of community use of school and city-ownedspace.

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

United Way co-chaired the 2002 Toronto City Summit, participated in the TorontoCity Summit Alliance, and was instrumental in calling for the establishment of a tri-partite agreement among the City of Toronto, the province and the federal govern-ment to support community services infrastructure, particularly in our poorest neigh-bourhoods.

Torontonians Speak Out (2003) - the result of extensive consultations across the city -described Torontonians’ profoundly mixed feelings about their neighbourhoods.Their clear pride of place is combined with concern about the onset of decline andurban decay in many parts of the city, and a shared anxiety about the lack of pro-grams, services and opportunities for youth. People spoke passionately about wantinga better life for their children. Perhaps the most poignant message was about growingstigmatization, fear that the rest of Toronto might abandon poorer neighbourhoods.

Poverty by Postal Code charts profound changes, the rapid, dramatic rise and intensi-fication in the number of high-poverty neighbourhoods, particularly in the formercities of North York and Scarborough. The response from governments and commu-nities must be prompt and comprehensive, aimed at transforming high-need neigh-bourhoods. The consequences of inaction are grave - for the present, and for thefuture.

United Way’s concern for Toronto’s future led us to examine families, family poverty,and the trends in the geography of family poverty in this report. Families comprise themost vulnerable, and the largest, group of people living in poverty, and foreshadowlimitations on the future, on individual futures, and the city’s future.

In response to these data and community consultations, United Way of GreaterToronto has established new priorities to help address the systemic causes that con-tribute to poverty. We will apply increased resources to building stronger neighbour-hoods, with an emphasis on newcomers and young people. The voluntary sector hasa strong role to play in addressing threats to the vitality of our neighbourhoods.We have an opportunity to take action before our neighbourhoods reach a crisis. Butwe must act soon. And we must act in partnership - government, business, labour,community organizations, and local residents - to turn the tide of neighbourhood neg-lect and decline.

Government action is crucial, and it must start with a renewed commitment to theconstruction of affordable housing. The expansion of poverty outside the downtowncore is inextricably linked to the search for lower housing costs, a search that is prov-ing increasingly elusive. Investments must be made in neighbourhood social infra-

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

structure - facilities, programs and social networks - a system that includes everythingfrom local parks and community centres to crisis intervention programs. These servic-es contribute to the health and vitality of neighbourhoods. They provide a social safe-ty net in times of vulnerability and foster social cohesion.

Finally, governments must review income supports, minimum wage, and programsdesigned to promote labour market attachment through training, employment, andthe economic integration of immigrants. Alleviating poverty cannot happen without acombination of renewed income supports and a market economy that promotesemployment. As a society, we have failed to make the most of newcomer skills and credentials. This failure has profound effects on not only individuals and families, butthe very cohesion and productivity of our community.

The statistics in Poverty by Postal Code are significant, and grim. Rather than provokedespair and paralysis, they can motivate a collective vision - a determination to pro-foundly change our city. Toronto’s greatest challenge is to restore and rebuild. Ourgreatest strength is our network of neighbourhoods, a network that connects citizensto one another, promotes the participation of children and youth, and welcomes new-comers. Revitalizing neighbourhoods is an opportunity to reclaim our legacy, while webuild a stronger future for everyone in Toronto.

Frances LankinPresident and CEOUnited Way of Greater Toronto

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

CONTENTSIntroduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Do Neighbourhoods Matter? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

The Research Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Poverty Amidst Prosperity: An Age of Extremes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

The Shifting Poverty Landscape . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

The Inner Suburban Story . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

The Changing Character of Higher Poverty Neighbourhoods . . . . . . . . . . .42

Summary & Implications: Putting Neighbourhoods on the Public Policy Agenda . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .54

Appendix One: Tables & Charts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61

Appendix Two: References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .74

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

1

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Neighbourhoods are enjoying a ren-aissance of public policy attention

today in a number of the developednations in the world. Fuelled by the needto make their cities more globally com-petitive, city and national governmentsare recognizing the need to tackle grow-ing poverty concentration, and the socio-economic problems that are entrenchingdisadvantage in their communities.

Nowhere has this renewal been moreevident than in Great Britain, where thegovernment of Prime Minister TonyBlair has taken unprecedented action to

address the decline in cities and townsacross that country. Beginning with the‘New Deal for Communities’ in 1998, itwill spend approximately £2 billion on39 of England’s most distressed commu-nities, and will combat growing problemsof poor job prospects, high levels ofcrime, educational underachievement,poor health, and deteriorating housingand physical environments.

In 2001, Britain followed the ‘New Dealfor Communities’ with a more compre-hensive plan – the ‘NeighbourhoodRenewal Strategy’ – with the ambitious

INTRODUCTION “A successful city neighbourhood isa place that keeps sufficiently abreast of its problems

so it is not destroyed by them”.

Jane JacobsThe Death and Life of Great American Cities

Poverty by Postal Code is a research study of the spatial concentration of fami-ly poverty in the City of Toronto over the past two decades. The study findingsare deeply disturbing. Twenty years ago, most 'poor' families in Toronto livedin mixed-income neighbourhoods. Today, they are far more concentrated inneighbourhoods with high levels of poverty. The increase in the number ofhigher poverty neighbourhoods in our city has been rapid, and they cover amuch broader portion of the city now than they did twenty years ago. The grow-ing spatial concentration of poverty has impacted certain vulnerable groupsmuch more acutely than others. And the challenge of growing numbers of high-er poverty neighbourhoods is something that the City of Toronto alone is fac-ing in the Greater Toronto Area.

In presenting the findings of this report, United Way of Greater Torontoemphasizes that it does not wish to stigmatize neighbourhoods or their resi-dents. Our aim is to raise public awareness of the stresses on many of our neigh-bourhoods; to influence government and community leaders to work togetherto develop strategies that will turn the tide of growing neighbourhood poverty.

2

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

goal of narrowing the socio-economic gapbetween its most deprived neighbour-hoods and the rest of England. Addinganother £1.875 billion pounds, the ulti-mate vision is that in 10 to 20 years, “noone (in that country) should be seriouslydisadvantaged by where they live.” Ineffect, the plan is to eliminate what theBritish refer to as ‘postal code’ poverty.

In the United States, the federal govern-ment has adopted an equally aggressiveapproach to revitalizing communities,investing billions of dollars in a range ofinitiatives. TheCommunityEmpowerment Fundsupports businessinvestment and jobcreation in distressedcommunities. TheEmpowerment Zonesand EnterpriseCommunity Initiative,targeted to areas ofpervasive poverty andhigh unemployment,are designed to help local businesses pro-vide more jobs and promote communityrevitalization. In 2001, EmpowermentZones were eligible for an additional $11billion for low-income housing. ACommunity Development Block GrantsProgram is directed toward revitalizingneighbourhoods, economic develop-ment, and providing community facilitiesand services.

These community revitalization strategiesare informed by a long tradition of neigh-

bourhood research in the United Statesand a new, flourishing one in GreatBritain. In the U.S., the interest in whatwas happening to its neighbourhoodsgoes back three decades, at the time ofthe flight of the middle and upper classesout of the inner cores of American cities,leaving deeply segregated and racializedpoor neighbourhoods in their wake. Alarge body of research has been built up,which has tracked these trends andattempted to understand the forces atplay in the growth and concentration ofpoverty at the neighbourhood level and

the process of neigh-bourhood decline.

In Canada, there havebeen two, targetedcommunity revitaliza-tion initiatives – one inVancouver and one inWinnipeg – governedby tri-paritite agree-ments among all threelevels of government ineach jurisdiction. The

aim is to improve the social and physicalinfrastructure of the distressed downtownareas in these cities, and enhance theeconomic opportunities of their resi-dents. While there have been other morenarrowly focused initiatives in certainjurisdictions, neighbourhoods inCanadian cities have not enjoyed thesame kind of public policy attention atsenior government levels as in GreatBritain and the United States. Nor hasthere been the same degree of interest inneighbourhood distress and the concen-

Just as governments in theUnited States and Europe

have been taking measures torevitalize their cities, Canadian

cities are beginning to showsevere signs of strain after

decades of rapid economicand population growth.

TD Economics: Special Report, 2002

3

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

tration of poverty at the neighbourhoodlevel among researchers and academicsuntil relatively recently.

But that is starting to change, sparked bythe now well documented growingincome disparity between the rich andpoor in our cities, and the intense atten-tion that the state of our cities is beinggiven by municipal politicians and com-munity leaders across the country. Andwhat the new research is telling us is thatthe number of neigh-bourhoods with highpoverty in the coun-try’s largest urbanregions is indeedgrowing [Hajnal(1995), Kazwmiparand Halli (1997),Hatfield (1997),Myles, Picot andPyper (2000),Kazemipur (2000)].

Ironically, while we inCanada are just begin-ning to turn our atten-tion to the intensification of neighbour-hood poverty, new U.S. research isshowing an astonishing turnaround in thenumber of high poverty neighbourhoodsin that country, declining by more thanone-fourth between 1990 and 2000, afterdoubling over the previous two decades(Jargowsky, 2003). A decade of strongeconomic growth in the 1990s and theimpact of the government’s revitalizationefforts are thought in large part to liebehind the improvements.

The concerted actions that other govern-ments are taking to revitalize their com-munities, and the evidence of their suc-cess, make it all the more worrying thatso little is being done in this country toaddress the signs of growing distress inour neighbourhoods. It raises many seri-ous questions about their future. Couldour neighbourhoods ever reach the levelof social deprivation and discord that hascharacterized poor neighbourhoods inthe U.S. and in England? Do we know

how, and do we havethe resolve to preventfurther decline?

To be sure, our socialhistories are different.The depth of theracial divisions creat-ing the highly segre-gated communities inthe U.S. have noprecedent in Canada.Nonetheless, researchhas shown there is astrong associationbetween race and

minority status, and living in neighbour-hoods of concentrated poverty inCanada [Kazwmipar and Halli (1997),Hajnal (1995)]. So perhaps the situationhere is not as dissimilar as we would liketo think.

It may also be true that the differencesrelate to the fact that our cities areyounger than their counterparts at leastin Great Britain, and that the decline inour distressed neighbourhoods simplylags behind theirs by a decade or so.

Toronto’s claim to fame hasbeen that of the well-planned,

liveable, yet urbane city with anexemplary quality of life.

Walking around many big U.S.cities – and then walking around

ours – it’s no longer safe toassume our primacy. I never

thought in my lifetime the tablesmight be turned.

Joe BerridgeReinvesting in Toronto: What the

Competition is Doing

4

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

One thing appears certain from the evi-dence that we have so far. We can nolonger afford to ignore how the growingincome disparities within our populationare impacting neighbourhoods. Torontohas always taken pride in its strong neigh-bourhoods. The Report of the GTATask Force in 1996 put it this way: “Ahealthy respect for neighbourhoods hasbeen a hallmark of communities acrossthe GTA” .... and, “this commitment topreserving and regenerating urban neigh-bourhoods, no longer as strong as it oncewas, needs to be rediscovered” (GreaterToronto: Report of the GTA TaskForce, 1996).

Our belief that healthy and inclusiveneighbourhoods are essential to the qual-ity of life of all Torontonians, and to thecreation of a strong and vibrant city pro-vides the impetus for this study of pover-ty concentration.

The study seeks to obtain a much betterunderstanding of what has been happen-ing to Toronto’s neighbourhoods overthe past two decades. It does this byexamining the changing geography ofneighbourhood poverty in the City ofToronto between 1981 and 2001. Itlooks at the increase in the number ofhigh poverty neighbourhoods, identifiesthe areas of the city which have experi-enced the greatest increase, and consid-ers how the resident profile of thesecommunities, as well as other ‘stressors’associated with high poverty concentra-tion have changed – factors like unem-ployment levels and low education.

The report tells an unsettling story. Notonly has the concentration of neighbour-hood poverty in Toronto been increas-ing, it has done so at a rapid rate. Therehas been a major shift in who has beenmost affected by growing poverty concen-tration. Today, residents of high povertyneighbourhoods are much more likely tobe newcomers to Canada and visibleminorities.

The findings raise many more questionsthat can be answered in this report, how-ever, our hope is that it will accomplishtwo purposes. First, that it will raiseawareness and stimulate public debateabout the changing nature of our neigh-bourhoods. Second, that it will serve as awake-up call for effective action. Torontois one of the primary economic enginesin the country, and we cannot afford tolet our neighbourhoods drift further andfurther into deepening poverty. Whilethe causes are complex and the solutionschallenging, they must be confronted ifToronto is to maintain the high quality oflife it has enjoyed for so many decadesand which has made it one of the bestcities in the world to live.

5

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

One school of thought would have itthat local neighbourhoods are less

important today because they have beenreplaced by ‘communities of interest’which now provide the social and sup-portive networks previously found inone’s local community. Additionally, themajority of urban dwellers can nowchoose to access a vast array of servicesand shops outside their immediate neigh-bourhoods.

While there may be some truth to this,neighbourhoods still have great impor-tance for most people, especially forthose who are less well off, and do nothave the same opportunities for makingconnections beyond their local commu-nities. For them, the neighbourhood isoften central to their social, recreationaland service needs.

If we think about the kinds of decisionsthat people make in their lives, few aremore important than where they chooseto live and raise their families. Selectingthe best neighbourhood and the bestaccommodation that they can afford is ofsingular importance. A recent survey ofover 20,000 households conducted bythe ESRC Centre for NeighbourhoodResearch in Great Britain confirms this

(Parkes et al 2002). Of a wide range ofneighbourhood characteristics, housingsatisfaction and the general appearanceof the area where they lived were the twofactors most strongly related to neigh-bourhood satisfaction among the peoplesurveyed.

But safe and attractive neighbourhoodsare not just important to the people liv-ing there; they are also fundamentallyimportant on a much larger scale – tothe economic health of the city overall,both today and in the future. Increas-ingly, cities and countries around theworld are recognizing the importance ofhealthy, inviting and affordable neigh-bourhoods as a critical element inattracting and retaining the kind of quali-fied workforce required to successfullycompete in the knowledge-based, globaleconomy. Neighbourhoods should beaffordable and appeal to upper, middle,and lower income workers.

This idea is captured in a City ofToronto report, which notes that“attracting the very mobile labour andintellectual capital that drives regionaleconomic development is highlydependent upon making that region anattractive place to live.” The report goes

DO NEIGHBOURHOODS MATTER?“Neighbourhoods are what make this city great. We mustvalue what is distinct about our neighbourhoods, and rec-

ognize that which has value beyond its cost”.

David MillerInaugural address, December 2, 2003

6

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

on to say that “this means providing cul-tural and recreational opportunities, asafe and healthy environment, and a vitalurban culture” (City of Toronto, 2000).

We know why attractive and affordableneighbourhoods are important to theindividual and why they are essential tothe economic vitality of the city as awhole; we also know what we do notwant our neighbour-hoods to become.

In its study of howneighbourhoodsdecline, CanadaHousing and MortgageCorporation paints astark portrait of the fac-tors that are associatedwith the declineprocess: poverty, highlevels of crime, conver-sion of single family homes to multi-fami-ly housing units, abandonment of hous-ing stock, out-migration of better-off fam-ilies to the suburbs, exit of retail busi-ness, conversion to lower forms of non-residential land use for businesses thatcater to the poor, decline in land values,increase in absentee landlords, poorbuilding maintenance, and the in-migra-tion of economically marginalized popu-lations. Once decline has reached a cer-tain point, CMHC suggests that it is verydifficult to turn the process of disinvest-ment around.

The Honourable Judy Sgro, in her TaskForce Report on Urban Issues, points tothe need to address the marginalizationof the poor in our cities, as a critical ele-ment of the broader reinvestment need-ed to ensure the long-term sustainabilityof our cities. She warns that “our urbanareas are home to a growing number ofvulnerable people and more must bedone to address social problems such as

poverty, drug andalcohol abuse, andmarginalization”(Sgro, 2002).

Finally, there is thequestion of how grow-ing up in a poor andmarginalized commu-nity may affect the lifechances of childrenand youth. A greatamount of research

has been done in this area, now knownas the study of “neighbourhood effects”.The idea is that the neighbourhood hasan influence on the lifeline of a person,independent of other factors such as thelevel of family poverty or a person’s edu-cation level – in effect, that the whole(the neighbourhood) is greater than thesum of its parts. The stigmatization of liv-ing in a distressed neighbourhood is oneway that ‘place’ can have an independ-ent, detrimental effect. The strength ofpeer influence when large numbers ofyoung people are living in circumstancesof socio-economic disadvantage is anoth-er.

The literature makes clearthat (neighbourhood)

disinvestment is the result ofdecline, and not its initial trig-ger. Once underway, declineand disinvestment tend to beevolutionary and accretive.

CMHC Disinvestment and the Decline of

Urban Neighbourhoods

7

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Certainly there is a well-documentedassociation in the research literaturebetween poverty and such adverse out-comes as poorer health, low birth weight,shorter life expectancy, lower educationalachievement, and lower reading and writ-ing abilities of children. A considerablebody of research has also found a strongassociation between living in a poorneighbourhood and a variety of health,social and developmental problems[Wilkins et al (2000), Boyle et al (1998),Kohen et al (1998), Ross & Roberts(1999), Hertzman (2002), Boardman etal (2001), Ross & Mirowsky (2001), Pearlet al (2001), Ainsworth(2002), Overman &Heath (2000), Crane(1991)].

Isolating the preciseimpact of the neigh-bourhood from otherimportant influences ona person’s life chances,such as the familyincome level and thequality of parenting inthe home, is extraordinarily difficult,however. Reviewers conclude that whileneighbourhood does make a difference,precisely how much is still uncertain[Seguin & Divay (2002), Diez Roux(2001)].

The significance of this has more to dowith public policy and the kinds of inter-ventions that are needed to improve thelife chances of people living in disadvan-

taged circumstances. No one argues thata healthy and safe neighbourhood isn’tessential to quality of life. The issue thatthe research on neighbourhood effectsraises is simply where best to target inter-ventions – at the individual or familylevel, or at the structural, neighbourhoodlevel.

In fact, the research strongly suggeststhat a comprehensive and integratedapproach is necessary to successfullyturn the tide of neighbourhood decline –an approach that focuses at both neigh-bourhood and individual levels. This

includes initiatives toimprove the social andphysical infrastructure,promote economicgrowth and enhanceeconomic opportuni-ties, reduce crime andrepair housing.Research also suggestsa strong need to buildcommunity capacity inlow-income disadvan-taged neighbourhoods,

by promoting partnerships among localorganizations and residents so that resi-dents can build the leadership skills andknowledge necessary to advance theinterests of the community.

When you apply for a jobyou never say you’re from

the Park. One of my friendsgot a job at a bank but he

didn’t put his address. Youhave to lie so they don’t think

you’re a thug.

United Way consultation with youngblack youth in Regent Park,

Summer 2002

8

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

THE RESEARCH APPROACHResearch on neighbourhoods indi-

cates that one of the prime triggersof neighbourhood decline is highly con-centrated poverty, and the associated‘stressors’ that accompany it – high levelsof unemployment, low education levels,and residential overcrowding, to namejust a few. This is why researchers in thiscountry have begun to show such interestin the growth in the concentration ofneighbourhood poverty.

But in almost all cases, their work hasfocused at the Census Metropolitan Area(CMA), which encompasses much largercity regions. The focus of this study is thepattern of neighbourhood poverty at thecity level, in this case, the City ofToronto.

PUTTING THE GEOGRAPHY OF

POVERTY INTO A WIDER CONTEXT

To understand the forces underlying thegrowth in poverty at the neighbourhoodlevel, our study begins by looking morebroadly at the increase in poverty andincome disparity in major urban centresin Canada, and particularly in theToronto region. The City of Toronto is the centre of amuch larger economic region, theGreater Toronto Area (GTA). At its coreis the old City of Toronto, circled byinner suburbs – the former municipali-ties of Etobicoke, York, North York,East York and Scarborough. Beyond theCity of Toronto boundaries lie the outer

suburbs – cities like Mississauga,Markham, Richmond Hill, and Whitby.While different governance structuresoperate within this huge region, it is, ineffect, one continuous expanse of resi-dential, commercial and industrial devel-opment, with its population linked byjobs, transportation systems, services, andhousing. Because the geographic distribu-tion of poverty across city-regions like theGTA follow distinctive patterns, with citycores typically exhibiting much higherpoverty levels than the outer, newer sub-urbs, it is important to understand if thispolarity is intensifying in the Torontoregion.

EXAMINING THE GROWTH AND CON-CENTRATION OF NEIGHBOURHOOD

POVERTY

This study examined the changing spatialconcentration of poverty in the City ofToronto in three ways, by:

Determining the percentage of the city's 'poor' families that were living in higher poverty neighbourhoods in each of the three years - 1981, 1991 and 2001;

Identifying the number of higher poverty neighbourhoods that existed at each of the three points in time; and,

Plotting the changes in neighbour-hood poverty over time on maps of the City of Toronto.

9

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

The study asked the following questions:

Has there been a change in the number of high poverty neighbour-hoods in the City of Toronto over this twenty-year period?

Has there been a change in the proportion of the city’s poor families that live in high poverty neighbour-hoods – in effect, has poverty becomemore concentrated?

Has there been a greater increase in the number and concentration of high poverty neighbourhoods in certain parts of the City, compared to others?

Has the resident profile of higher poverty neighbourhoods changed?

Are there differences between the City of Toronto and the rest of the Toronto CMA1, in terms of the change in the number of high poverty neighbourhoods?

FOCUSING ON FAMILIES

To answer these questions, the economicfamily was selected as the primary focusof analysis (see definition on next page).It should be noted that this measuretends to undercount the incidence of

family poverty because families who aredoubled or tripled up – a practice whichUnited Way member agencies report iscommon in many of Toronto’s poorest,and most densely populated communi-ties – are counted as only one ‘economicfamily’. Our results will therefore besomewhat conservative.

SOURCES OF DATA

All neighbourhood income and popula-tion data are derived from the long-form,20% sample of the 1981, 1991 and 2001census. Poverty is measured usingStatistics Canada’s, pre-tax low-incomecut-offs (LICO), which is the only meas-ure available from the census (see defini-tion next page).

DEFINING NEIGHBOURHOOD

Census tracts are used to define neigh-bourhoods. There were 428 censustracts in 1981 with sufficient data to per-mit analysis, 476 in 1991, and 522 in2001. While they by no means perfectlydefine how local residents would delimittheir neighbourhoods, they are the bestmeasure available to us to quantifychanges in poverty concentration overtime.

DEFINING HIGH POVERTY NEIGH-BOURHOODS

Our definition of high neighbourhoodpoverty is derived from researchers whohave previously studied the spatial con-centration of poverty in both Canadaand the United States. Using their work

1Toronto CMAThe Toronto Census Metropolitan Area includes theCity of Toronto, plus 23 surrounding municipalities:Ajax, Aurora, Bradford, West Gwillimbury,Brampton, Caledon, East Gwillimbury, Georgina,Halton Hills, King Township, Markham, Milton,Mississauga, Mono Township, Newmarket,Tecumseth, Oakville, Orangeville, Pickering,Richmond Hill, Uxbridge, Whitchurch-Stouffvilleand Vaughan.

10

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

as a model, we have established four lev-els of neighbourhood poverty, againstwhich changes in Toronto’s neighbour-hoods are tracked.

We begin with Hatfield’s definition of‘high’ poverty neighbourhoods, which isa measure double or greater than thenational average poverty rate of econom-ic families. By selecting the 1981 averagepoverty rate of 13.0%, then 26.0%becomes the level at which neighbour-hoods are considered to be in ‘high’poverty. We then adapted Hatfield’s

measure by using the 1981 average as afixed measure against which changes aretracked in Toronto neighbourhoods in1991 and 2001.

To define ‘very high’ poverty levels, wedraw upon the work of U.S. researchers.Although a 30% neighbourhood povertyrate has sometimes been applied, 40%has now become the more commonlyused measure in the U.S. to identifyextremely distressed communities.(Jargowsky, 1997; Jargowsky, 2003;Kingsley et al, 2003).

ECONOMIC FAMILY

Statistics Canada defines the economic family as a group of two or more persons who live inthe same dwelling and are related to each other by blood, marriage, common-law or adop-tion. By definition, all persons who are members of a census family are also members of aneconomic family. Examples of the broader concept of economic family include the follow-ing: two co-resident families who are related to one another are considered an economicfamily, and two co-resident siblings who are not living with parents are considered an eco-nomic family.

LOW-INCOME CUT-OFF (LICO)The LICO is a measure developed by Statistics Canada to compare the relative economicwell-being among Canadian households. We use the pre-tax LICO, which is the only meas-ure of low-income available from the census. The LICO has traditionally been used bysocial researchers as a measure of poverty and is the one used in this study. The LICOexpresses the amount of income that a family of a particular size and living in a particularurban area, would need to live. Families with incomes lower than this amount are said to bein ‘straightened circumstances’. Using this measure, a Toronto family of a husband and wifeand two children in 2004 is considered poor if their income is less than $36,247.

CENSUS TRACTS

A census tract is defined by Statistics Canada as a relatively compact, permanent area,resembling a small urban neighbourhood or rural community, which follows permanent andeasily recognizable physical features. Census tracts have a population ranging from 2,500 to8,000 (4,000 is the preferred level ) and to the greatest extent possible, social and economichomogeneity. In 2001, there were 527 census tracts in the City of Toronto, of which datawas reliable for 522.

11

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

On this basis, the level of family povertywithin neighbourhoods was categorizedinto the following ranges:

LLower PPoverty:

0 - 12.9% (below the Canadian average poverty rate of economic families in 1981)

MModerate PPoverty:

13.0 - 25.9% (above, to nearly double the national 1981 average)

HHigh PPoverty

26.0 - 39.9% (double the national 1981 average to 39.9%)

Very HHigh PPoverty

40% + (more than three times the national 1981 average)

If the efforts of society, the economy andgovernments have been productive, thenone would expect that rates of ‘high’poverty and ‘very high’ poverty neigh-bourhoods in 1991 and 2001 would be atleast equal to those of 1981, if not lower.However, should there have beenchanges that increase the level of povertyprevailing in Canada, as measured usingLICO figures, over the period from 1981to 2001, then our fixed levels will showan increase in the number of neighbour-hoods that can be considered as ‘high’ or‘very high’ poverty. It must be remem-bered that the aim of the analysis is notto compare poverty levels to somenational average at each point in time,since this simply masks any generalincrease. Rather, the aim is to establish afixed level – we have chosen two, ‘high’and ‘very high’ – and to see how there

has been fluctuation around this fixedpoint over time. Unlike inflation, rates ofpoverty over time do not have to be stan-dardized, as they are adjusted annuallyfor inflation.

DEFINING POVERTY CONCENTRATION

In this study, poverty concentration isdefined as the percentage of all poor fam-ilies in a geographic area that reside inhigher poverty neighbourhoods. The geo-graphic areas that were examined werethe entire City of Toronto, and each ofthe former municipalities that make upthe new City of Toronto.

DEFINING GEOGRAPHIC VARIATIONS

A key question is whether there havebeen variations across the city in thenumber of high poverty neighbourhoodsand the concentration of neighbourhoodpoverty. This is important because thesocial infrastructure in Toronto is heavilyconcentrated in the city centre, and ifneed is growing at a faster rate in theinner suburbs, this has implications forwhere new investments in social infra-structure should be directed.

To gain an understanding of geographicvariations, the neighbourhood povertydata was analyzed using the boundaries ofthe former municipalities which nowmake up the new City of Toronto –Toronto, Scarborough, North York,York, Etobicoke, and East York.

12

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Our focus on neighbourhood povertymay seem incongruous, at first

glance, given the prosperity that has typi-fied the Toronto region for so manyyears. It is, after all, one of the prime gen-erators of wealth in the country, account-ing for 44% of the Ontario’s GDP, mak-ing it and the Province of Ontario majoreconomic engines in the country (Sgro,2002). It houses 40 per cent of Canada’shead offices, and has an impressive arrayof highly competitive industry clusters,including financial services, bio-medical,aerospace, and automotive. These indus-tries are generally considered to haveweathered, extremely well, the majorrestructuring of the economy in the1990s, and the shift from a largelyCanadian market to a North American,and in many cases, global market, (TDBank Financial Group, 2002). Today,Toronto’s food and beverage manufactur-ing sector and its automotive industryrank second largest in North America, itsfinancial services sector third largest, andits biomedical & biotechnical industryfourth largest (Toronto City SummitAlliance, 2003).

The success that Toronto has achievedhas brought it world-wide recognition asone of the best cities in which to live. In2000, it ranked as the 7th best place tolive in North America, by the PlacesRated Almanac, based on job markets,cost of living, educational standards,quality of public transportation, healthcare, recreational facilities, and crimerates. And it was ranked 12th of 215cities worldwide in William M. Mercer’sQuality of Life Survey, which considerspolitical, social, economic, health, educa-tion, recreation, housing, and environ-mental factors (2003).

With its highly skilled labour force,young population, institutions of higherlearning, and culturally and linguisticallydiverse population, the Toronto region isthought by many to be well positioned tosustain its prosperity and competitivenessin the next decades.

Yet, there is a deep unease in Toronto,as there is in other cities in the country,about whether they can truly keep upwith the competition from cities in other

POVERTY AMIDST PROSPERITY: AN AGE OF EXTREMES“With the shift to cities, many of society’s inequitiesand ills are also becoming more and more urban.

We see stark contrasts: contrasts in wealth and opportunity;contrasts in urbanization patterns; and

contrasts between housing costs and the salariesoffered by labour markets”.

Kofi Annan, Secretary-General, United NationsConference on Sustainable Urban Development

Moscow, June 5, 2002

13

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

countries. The reason has to do with thedeclining state of the physical and socialinfrastructure in our cities, and the lackof financial tools at their disposal to dothe necessary rebuilding that has beengoing on in competitor cities in the U.S.and elsewhere. Much has been written inthe last few years about our cities’ lack ofa diverse revenue base, their over-reliance on property taxes, and the factthat they have not enjoyed the kind ofreinvestment from senior levels of gov-ernments that has occurred elsewhere.There is widespread concern that unlessthese financial tools are made available,Canadian cities may soon start to fallbehind.

But it is not just the need for reinvest-ment in infrastructure that is causing con-cern. There is also wide recognition thatsuccessful cities of the future will have tooffer attractive, vibrant and inclusivecommunities – ones that not only pro-vide good jobs, but also are places wherepeople will want to live. Hence, thegrowth of poverty in our cities is consid-ered to be a serious detriment to theirfuture health – and nowhere has thistrend been more acutely felt than in theCity of Toronto.

The problem is that Toronto is losingground faster than most other urbanregions in the country. It is this trendwhich we want to highlight in this sectionof the report, in order to put our exami-nation of the spatial aspect of growingpoverty in the City of Toronto into abroader context.

REASONS FOR GROWING POVERTY

The trends of growing urban poverty andincome disparity between rich and poor,which are occurring in cities around theworld, are thought to be getting worsebecause of the impact of economicrestructuring on vulnerable workers, theloss of jobs in the manufacturing sector,the high cost of urban living, and an ero-sion of the social safety net which hastaken place in many countries, includingCanada. And it is the core areas of cityregions that have been the most seriouslyimpacted by these changes.

If we look at employment growth as anexample, we see that the City of Torontois lagging significantly behind the rest ofthe city region. Over the last five years,the employed labour force in theToronto CMA, excluding the City ofToronto, grew by 23%. In the City ofToronto itself, the rate was only 11.7%,or roughly half the growth rate in theouter regions. And while Toronto's num-bers were better than the Canada averageat 10.3%, the momentum in growth isclearly in suburbs such as Richmond Hill(38%), Vaughan (46%), Brampton (27%)and Markham (26%) (see Table 1.1 inAppendix One).

Not only has there been slower growth injobs, but most of these jobs have been inthe lower paying service sector, while asizeable number of higher paying manu-facturing jobs have disappeared. In thetwenty year period from 1983 to 2003,

14

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

total jobs in the manufacturing sector inthe City of Toronto declined by 73,213 –a 30% loss. The losses in certain sectorshave been particularly heavy (see Table1.2 in Appendix One for sectoral break-down).

At the same time as good paying, stablejobs have been lost, the cost of accom-modation has continued to rise, and thesocial safety net has weakened. Datafrom the 2001 census indicate thatapproximately 197,270 tenant house-holds had affordability problems in theCity of Toronto, spending 30% or moreof their total household income on rent.This equates to 43.2% of all ten-ant households experiencinghousing affordability issues, or 4out of every ten tenant house-holds (Chart 1.1 in AppendixOne).

There have been no increases insocial assistance rates since 1993,and a 21.6% reduction in benefitsin 1995. The levels established atthat time have since lost ground toinflation each year. The new mini-mum wages, while an improve-ment, do not provide a livingwage; a single parent with onechild would need to earn almosttwo times the minimum wage tobe above the Statistics Canadalow-income cut-off for a family ofthis size living in Toronto. Andthe barriers to economic integra-tion that newcomers face – gettingaccreditation and finding employ-

ment in the fields for which they aretrained – are forcing many newcomerfamilies into poverty.

Added to all these trends were the eco-nomic cycles of slow, then robust growthwith which vulnerable workers have hadto contend: from the poor economicconditions that existed in the early 1980s,which were followed by a period of eco-nomic recovery, to the deep recession ofthe early 1990s, which was again followedby economic growth, lower unemploy-ment and a general recovery.

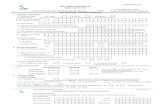

CHANGE IN MEDIAN INCOME FOR CANA-DIAN CENSUS FAMILIES, CANADA ANDLARGE CMAs, 1990-2000 (CONSTANT 2000$)

TABLE 1

MEDIAN INCOME

($)PERCENTAGE

CHANGE

1990 2000 1990 -2000

CANADA 54,560 55,016 0.8

MONTREAL 53,624 53,385 -0.4

OTTAWA-HULL 68,088 69,518 2.1

TORONTO 66,520 63,700 -4.2

HAMILTON 61,260 63,031 2.9

WINNIPEG 53,755 55,634 3.5

CALGARY 61,408 65,488 6.6

EDMONTON 58,242 60,817 4.4

VANCOUVER 60,254 57,926 -3.9

Source: Statistics Canada, 96F0030XIE2001014, Census 1991 & 2001

INCOME GAP IN TORONTO WIDEST IN

THE COUNTRY

Evidence of greater financial stress in theToronto region is seen in the incomegap between rich and poor. For Canadaas a whole, there was a substantial$174,729 dollar gap between families inthe bottom 10%, ranked by averageincome, compared to families in the top10%. But what is alarming, is how verymuch larger that gap was in the Torontoregion – a difference of $251,471. Thismeans that families in the Torontoregion in the highest decile had 27.3times the income of families in the low-est decile (Table 2).

15

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Not everyone shared in the recoveries,and large portions of the population areexperiencing growing financial insecurity.

A DECADE OF DECLINING MEDIAN

INCOME

One way to see how Torontonians arelosing ground is to look at what has hap-pened to median incomes.1 In the coun-try as a whole, the median family incomebarely budged over the last decade, ris-ing by just 0.8% in real dollars (Table 1).For some city regions, however, medianincomes actually went down; this is thecase for the Toronto CMA whereincomes dropped by 4.2%, the largestdecline of any of the largestcensus metropolitan areas inthe country. Only Vancouver,with a decline of 3.9% wasnear Toronto’s. In other cityregions, median incomes grewbetween 1990 and 2000, mostnotably in Calgary where theincrease was 6.6%, but also inEdmonton, Winnipeg,Hamilton and Ottawa.

1 Median incomes of Canadianfamilies are determined by sortingall families in order of earnings andthen by picking the family in themiddle of the list, the median fami-ly is determined. Half of all fami-lies have more income, half have

AVERAGE INCOME($)

INCOME OF THOSEIN THE HIGHEST

DECILE FOR EVERYDOLLAR OF

INCOME OF THOSEIN LOWEST DECILE

LOWESTDECILE

HIGHESTDECILE

CANADA 10,341 185,070 17.9

MONTREAL 10,405 179,725 17.3

OTTAWA-HULL 12,823 214,037 16.7

TORONTO 9,571 261,042 27.3

WINNIPEG 11,429 169,626 14.8

CALGARY 13,037 248,604 19.1

EDMONTON 11,949 184,642 15.5

VANCOUVER 8,723 205,199 23.5

AVERAGE INCOME OF CENSUS FAMILIES INLOWEST AND HIGHEST INCOME DECILES,CANADA & CMAs, 2000 (CENSUS 2001)

TABLE 2

Source: Statistics Canada, 96F0030XIE2001014

16

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

THE NEIGHBOURHOOD INCOME GAP

When we examine the poverty gap at theneighbourhood level in the City ofToronto, we see the same stark differ-ences. The average family income in thebottom 10% of neighbourhoods actuallydeclined between 1981 and 2001, from$41,611 in 1981 to $39,298 in 2001(constant 2000$). Even when the bottom25% are considered, we still see a drop inreal income over the two decades, from$45,462 to $44,773 (Table 3).

The exact opposite trend is observed inthe richest 25 per cent or the richest 10per cent of neighbourhoods by averagecensus family income. Here, the richestneighbourhoods experienced continuousand very large increases in average censusfamily income. Over the 1981 to 2001period the top 10 per cent of neighbour-hoods experienced an average increaseof about $85,000 in constant dollars, or59%.

THE GROWTH IN POVERTY

The trends in poverty show a similar pat-tern of greater financial stress in the Cityof Toronto. In the country as a whole,the rate of poverty among economic fam-ilies remained fairly flat over the lasttwenty years, actually dipping slightly by2001 (Table 4). The rates were higheramong the 25 largest census metropolitanareas, as one would expect given thetrend of greater poverty in urban areas.But, as in the country as a whole, theaverage rate of the 25 CMAs haddecreased slightly in 2001, from 1981 fig-ures.

In the Toronto CMA, the low-incomerate for families in 1981, at 11.4%, waslower than the national and average rateamong all 25 CMAs in that year, but by2001 it stood at 14.4%, surpassing bothrates. Thus, contrary to the nationaltrend of stagnation, the Toronto regionaltrend had moved higher (Table 4).

1981 1991 2001

BOTTOM 10% OF CTs (constant 2000$) $41,611 $43,976 $39,298

BOTTOM 25% OF CTs (constant 2000$) $45,462 $49,252 $44,773

TOP 25% OF CTs (constant 2000$) $103,289 $125,472 $150,853

TOP 10% OF CTs (constant 2000$) $135,801 $170,018 $221,111

RATIO OF BOTTOM 25% TO TOP 25% OF CTs 2.3 2.5 3.4

RATIO OF BOTTOM 10% TO TOP 10% OF CTs 3.3 3.9 5.6

CENSUS FAMILY AVERAGE INCOME PER CENSUS TRACT

TABLE 3

Source: Statistics Canada, 96F0030XIE2001014

17

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Of great significance is the pronouncedpoverty trend that occurred in the City ofToronto, where the total number of eco-nomic families increased 15.3% between1981 and 2001, compared to the muchlarger 68.7% rise inthe total number of‘poor’ families.

This disproportion-ate rise in the num-ber of ‘poor’ fami-lies over the twenty-year period, causedthe family poverty rate to rise from13.3% in 1981, to 16.3% in 1991, to19.4% in 2001. This means that by 2001,nearly one in every five families was liv-ing in poverty (Table 4).

Finally, it is instructive to examine thegrowth in poverty rates in the City ofToronto compared to other cities in theToronto region. Looking at the povertylevel of the entire population (not just

families), we see thatthe City of Torontohad by far the largestpoverty rate in 2000at 22.6%. This wasnearly double thenext closest rate of12.7%, which was inthe city of

Mississauga. (See Table 1.4 in AppendixOne for poverty rates of individualsmunicipalities within the TorontoCMA).

RATE OF POVERTY AMONG ECONOMIC FAMILIES, CANADA, TORONTOCMA, CITY OF TORONTO

1981 1991 2001 % CHANGE

1981-2001

CANADA 13.0% 13.2% 12.8%

AVERAGE OF 25 LARGEST CMAs 14.1% 13.0% 13.9%

TORONTO CMA 11.4% 12.4% 14.4%

CITY OF TORONTO (CSD 2001) 13.3% 16.3% 19.4%

NUMBER OF FAMILIES 556,300 586,800 641,400 15.3%

NUMBER OF POOR FAMILIES 73,900 95,800 124,700 68.7%

TABLE 4

Source: Statistics Canada, Census 1981, 1991 and 2001

The number of ‘poor’ familiesin the City of Toronto increasedby almost 69% between 1981 and

2001, compared to just a 15%increase in the number of

families overall.

18

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Falling median incomes, wideningincome gaps between rich and poor,

and rising poverty levels are having a pro-found effect on the spatial distribution ofpoverty in Toronto. The examination ofthe nature and magnitude of this changeis the focus of this section of the report.

To understand what has taken place, it isimportant to first consider where low-income families lived in the city prior to1981, when our analysis begins.

Traditionally, many of Toronto’s poorestfamilies have been concentrated in publichousing buildings that were built in the1960s and early 1970s, which housedpeople on the basis of greatest need.Hence, poverty concentration was largelythe result of public policy, rather than thenatural settlement patterns of families.The location of these public housingdevelopments create the familiar poverty‘U’, starting in the Jane-Finch area in thenorth-western part of the city, downthrough the former City of York, to theParkdale community, across the southernportion of the city to Alexander Park,Regent Park and Moss Park, and acrossto a few scattered neighbourhoods in theeast, in the former City of Scarborough.Private rooming and boarding houses in

the Parkdale and downtown areas of thecity, and housing adjacent to the railwayin the western part of the city also pro-vided relatively inexpensive accommoda-tion for families and individuals with lowincomes, filling out the poverty ‘U’. Inspite of this distinctive pattern of povertyconcentration, however, the vast majorityof families living in poverty were widelydispersed in mixed neighbourhoodsacross the former cities.

A number of changes have taken placesince the early 1980s that have affectedthe residential options of low-incomehouseholds. The cost of rental housingin the city has soared. Over just a ten-year period, between 1992 and 2002, theaverage rental cost in Toronto (in current2002 dollars) increased 42.1%,1 yet in the1990s, median incomes of Torontohouseholds declined (UWGT andCCSD, 2002). Rooming and boardinghouse stock has been lost, and gentrifica-tion has put once affordable neighbour-hoods beyond the reach of low-incomehouseholds. In addition, almost no newassisted housing has been built for nearlya decade.

THE SHIFTING POVERTY LANDSCAPE“Quality of life isn’t something that exists in isolation. Our

quality of life is shaped by our economic opportunities and thedegree to which we can all share in our city’s prosperity.”

Toronto at a Crossroads: Shaping Our FutureCity of Toronto

1 CMHC Rental Market Survey

19

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

While these changes were taking place,the demand for affordable neighbour-hoods has grown. This is not just theresult of increasing poverty, but alsobecause many of the more than 50,000newcomers arriving each year in the city,who must struggle to get an economicfoothold in their new home, have a greatneed for affordable housing.

This study questions how settlement pat-terns of low-income families havechanged, in light of the high cost ofurban living, declining affordable housingoptions, and stagnating incomes. Haveexisting pockets of high poverty expand-ed geographically? Are there new pock-ets of concentrated poverty, and if so,how many more? Has the profile of thefamilies living in these neighbourhoodschanged?

MAPPING THE POVERTY LANDSCAPE

Plotting the changes in poverty by censustract enables us to observe how neigh-bourhoods are spatially distributed andhow the geography of poverty haschanged over time.

The maps on page 21 show the level offamily poverty within each census tract,using the poverty levels discussed onpage 11. The colours on the map corres-pond to the following family povertyranges in neighbourhoods:

Neighbourhoods with family povertyrates in the 0-12.9% range (white on themaps) are ones that are below the aver-age poverty rate of economic families inCanada in 1981. In other words, theseare neighbourhoods that were doing bet-ter than the Canadian average. All otherneighbourhoods have family povertyrates that exceed the 1981 national aver-age.

Two aspects about the 1981 map arestriking. One is the distinctive poverty‘U’ described previously. The second isthe number of Toronto neighbourhoodsthat had ‘lower’ poverty rates in 1981 –228 of 428 neighbourhoods, or 53% ofthe total. Twenty years later, Toronto’sneighbourhoods had fallen far behind,with only 177 of 522 neighbourhoodswith poverty levels below what the aver-age family poverty level had been in1981.

The visible changes are dramatic in the1991 and 2001 maps. We see large por-tions of the city that had ‘lower’ povertyin 1981 now having ‘moderate’, ‘high’,and even ‘very high’ poverty levels by2001. The poverty ‘U’ has been replacedby a shape more like an ‘O’ around par-

0 -12.9 % . . . . . .LOWER POVERTY

13.0 - 25.9 % . .MODERATE POVERTY1

26.0 - 39.9 % . .HIGH POVERTY

40.0%+ . . . . . . .VERY HIGH POVERTY

1 Moderate PovertyThe term ‘moderate poverty’ is used to differ-entiate between ‘lower’ and ‘high’ levels ofpoverty. However, census tracts with povertylevels at the upper end of the ‘moderatepoverty’ range, approaching the level which isdouble the national average rate, actually havequite significant poverty levels.

ticular affluent areas in the former citiesof Toronto and Etobicoke.1

Another striking aspect of the changethat occurred over the twenty-year periodis the large growthin neighbourhoodpoverty in the innersuburbs, especiallyin the north-westernpart of the city inwhat was the formerCity of Etobicoke,across the formerCity of North York, to the east, overmuch of the former City of Scarborough.

THE GROWTH IN HIGH POVERTY

NEIGHBOURHOODS

With the declining number of ‘lower’poverty neighbourhoods, there was, ofcourse, a corresponding increase in the

number of neigh-bourhoods withpoverty rates abovethe 1981 average,from 46% in 1981,to 66% in 2001.

The largest increasewas in the number of ‘moderate’ povertyneighbourhoods, which grew from 166in 1981 to 223 in 2001 – a 34% increase.However, the greatest percentageincreases were in the ‘high’ and ‘very

20

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

There has been a dramatic rise inthe number of higher2 poverty neigh-

bourhoods in the City of Torontobetween 1981 and 2001, approxi-mately doubling every ten years.

CITY OF TORONTO

(TORONTO CSD) 3 1981 1991 2001

% CHANGE1981-2001

LOWER POVERTY (0-12.9%) 228 220 177 -22.4

MODERATE POVERTY (13 -25.9%) 166 189 223 34.3

HIGH POVERTY (26 -39.9%) 26 57 97 273.1

VERY HIGH POVERTY (40% +) 4 9 23 475.0

NUMBER OF NEIGHBOURHOODS BY FAMILY POVERTY RATE

TABLE 5

Source: Statistics Canada, Census 1981, 1991 and 2001

1A map of the City of Toronto showing the boundaries of the former municipalities is shown inChart 1.2 in Appendix One, as a reference for reading the maps on pages 21, and 31 thru 41.

2Higher Poverty: Throughout the report the term ‘higher’ poverty neighbourhoods is used when the

data for both ‘high’ and ‘very high’ poverty neighbourhoods are combined.

3Toronto CSD: All 1981 and 1991 neighbourhood data in Tables and Charts throughout the reportare based on the boundaries of the new City of Toronto (Toronto CSD), and include the formermunicipalities of Toronto, Scarborough, North York, York, Etobicoke, and East York.

21

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Toronto

Toronto

CITY OF TORONTO - POVERTY LEVEL BY NEIGHBOURHOOD

1981

1991

2001

0 -12.9 %13.0 - 25.9 %26.0 - 39.9 %40.0 - 70.0%

0 -12.9 %13.0 - 25.9 %26.0 - 39.9 %40.0 - 65.0%

0 -12.9 %13.0 - 25.9 %26.0 - 39.9 %40.0 - 73.0%

(2001 BOUNDARIES)

22

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

high’ poverty categories (Table 5 & Chart1).

In 1981, there were 26 ‘high’ povertyneighbourhoods and just 4 with ‘veryhigh’ levels, for a total of 30 neighbour-hoods that were double or greater thanthe average poverty rate of economicfamilies in the country in that year.

Ten years later, the number of ‘high’poverty neighbourhoods had increased to57, and ‘very high’ to 9, for a total of 66.

Ten years after that, in 2001, the numberof ‘high’ poverty neighbourhoods had

climbed to 97 and ‘very high’ to 23, for atotal of 120.

Clearly, there are a great many morepockets of high poverty today in the Cityof Toronto than there were twenty yearsago, approximately doubling every tenyears, from 30, to 66 to 120.

A similar trend is observed if you consid-er just the ‘very high’ poverty neighbour-hoods. By 2001 the number was nearlysix times what it was in 1981.

When considering these changes, itshould be noted that the total number ofcensus tracts in the City of Torontoincreased between 1981 and 2001, inresponse to the overall populationgrowth, and Statistics Canada’s policy ofkeeping census tracts within a particularsize range. One question could bewhether the large increase in the numberof higher poverty neighbourhoods is sim-ply a reflection of the subdivision of cen-sus tracts. Our analysis, however, tells usthat census tract subdivision accountedfor a very small amount of the growth inhigher poverty neighbourhoods.

NUMBER OF HIGH AND VERY HIGHPOVERTY NEIGHBOURHOODS

Source: Statistics Canada, Census 1981, 1991, and 2001

Chart 1

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

23

THE GEOGRAPHY OF POVERTY IN THE

REST OF THE TORONTO REGION

As the City of Toronto is part of a muchlarger economic region, it is important toconsider the geogra-phy of poverty in thewider, city-region con-text, in order tounderstand if the pat-terns in the rest of theregion are also chang-ing.

Table 6 shows thechange in the number of ‘moderate’,‘high’ and ‘very high’ poverty neighbour-hoods between 1991 and 2001, for theCity of Toronto and the rest of theToronto CMA.

What is most significant is the fact thathigher poverty neighbourhoods are

almost exclusively a City of Torontophenomenon. While the number of‘very high’ poverty neighbourhoods inthe City of Toronto grew from 9 to 23between 1991 and 2001, the rest of the

region had none ineither year. Andwhile the number of‘high’ poverty neigh-bourhoods in theCity of Torontoincreased from 57 to97 over the ten-yearperiod, the rest of

the region had none in 1991, and onlyone in 2001.

Although higher poverty neighbour-hoods are exclusive to the City Toronto,the number of neighbourhoods with'moderate' poverty levels has grown sub-stantially in the rest of the CMA, from31 in 1991 to 82 in 2001 – a 165%

High poverty neighbourhoodsare almost exclusively a

City of Toronto phenomenon,with only one neighbourhoodoutside of the City with ‘high’

poverty in 2001, and none with‘very high’ poverty.

NEIGHBOURHOOD POVERTY IN THE TORONTO CMA

Source: Statistics Canada - Census 1991 and 2001

1991 Economic Families 2001 Economic Families

City ofToronto(2001borders)

Rest ofTorontoCMA(2001borders)

TorontoCMA

City ofToronto(2001borders)

Rest ofTorontoCMA(2001borders)

TorontoCMA

Poverty Rate 16.3 7.1 12.4 19.4 8.8 14.4

Number ofNeighbourhoodsby Poverty Level

ModeratePoverty 189 31 220 223 82 305

High Poverty 57 0 57 97 1 98

Very HighPoverty 9 0 9 23 0 23

TABLE 6

24

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

increase in just ten years. This suggeststhat in the CMA the intensification ofneighbourhood poverty may be in theearly stages.

THE GROWTH IN CONCENTRATION

OF ‘POOR’ FAMILIES

The increase in the number of higherpoverty neighbourhoods is one way tolook at the geographic intensification ofpoverty in a city. Another is to determinethe percentage of an area’s total poorpopulation that is living in higher povertyneighbourhoods.

The data show a dramatic increase in theconcentration of family poverty in theCity of Toronto from twenty years ago,when ‘poor’ families were much moredispersed across the city, and more likely

to be living in mixed-income neighbour-hoods.

In 1981, just 17.8% of poor economicfamilies resided in higher poverty neigh-bourhoods. By 1991, this had climbed to29.6%, and by 2001, it had reached43.2% (Table 7).

The concentration of ‘poor’ families in‘very high’ poverty neighbourhoods wasrare twenty years ago, with just 3.4% of‘poor’ families living in these communi-ties. But by 2001, more than one in ten‘poor’ families resided in neighbour-hoods with this extreme level of poverty.

It may seem that these finding contradictthe picture of geographically spreadingpoverty that is illustrated on the maps onpage 21. Yet, both trends – spreadinghigh neighbourhood poverty, and theincreasing concentration of families inhigh poverty neighbourhoods – are tak-ing place at the same time.

1981 1991 2001

HIGH & VERY HIGH

POVERTY

NEIGHBOURHOODS

17.8% 29.6% 43.2%

VERY HIGH POVERTY

NEIGHBOURHOODS3.4% 5.7% 11.4%

CONCENTRATION OF POVERTY

TABLE 7

Source: Statistics Canada - Census 1981, 1991 and 2001

25

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

In 1998, the six former municipalitiesthat made up the Municipality of

Metropolitan Toronto amalgamated tocreate the new City of Toronto. The old-est of these was the old City of Toronto,which dates back to the early nineteenthcentury, and which became the commer-cial and financial hub of the region. Bythe first few decades of the twentieth cen-tury, much of its residential areas werefully developed. Four of the remainingformer municipalities – Etobicoke,Scarborough, North York, and York –developed much later. Although somewere formed out of earlier amalgama-tions of existing villages and towns, mostof the lands in each suburb were built uprapidly in the post-war years of the 1950sand 1960s. New and modern, theyoffered families the suburban dream ofthe single family home.

In 1979, twenty to thirty years after mostof the development had been completed,the Social Planning Council ofMetropolitan Toronto undertook a com-prehensive study of the suburbs. A fol-low-up report entitled, Planning Agendafor the Eighties - Part II: Metro’sSuburbs in Transition, called upon thegovernment of the day to assume greaterleadership in addressing economic andsocial needs that were emerging in thesuburban communities. The suburbswere becoming home to increasing num-bers of single parents, newcomers,

THE INNER SUBURBAN STORY

unemployed, and youth, and the reportidentified an urgent need for communityservices to address their needs. It waspredicted that inaction could ultimatelylead to the flight of the middle classes, ashad happened in American cities.

Now, a quarter of a century later, it isimportant to look at how the poverty lev-els as well as other socio-economic char-acteristics have changed in the inner sub-urbs.

In this section of the report, each of theformer municipalities is considered sepa-rately. But a number of general observa-tions are highlighted first.

GENERAL TRENDS ACROSS THE CITY

The first significant point is the fact thatthere has been a continuous rise in thepoverty rate among economic families inall the former municipalities over the lasttwo decades, with the exception of theformer City of Toronto. Here it declinedbetween 1991 and 2001, after increasingover the previous decade. By 2001, theformer cities of York, North York andScarborough all had poverty levels wheremore than one in every five of their fami-lies were living in poverty (Table 8).

A second important trend is in the con-centration of poverty, which increasedcontinuously over the twenty-year periodin all the inner suburbs. In 1981, the for-

26

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

mer City of Toronto had the highestconcentration of family poverty. By2001, North York, East York and Yorkhad the highest lev-els. In all three ofthese areas, abouthalf of their ‘poor’economic familieslived in higher pover-ty neighbourhoods(Table 8).

A third trend is theshift in the prevalence of higher povertyneighbourhoods from the central city tothe inner suburbs. In 1981, the old Cityof Toronto had half of all the higherpoverty neighbourhoods. By 2001, it hadonly 23% of the total, while the inner

suburbs accounted for a combined 77%(Table 9).

LOCATION OF

‘VERY HIGH’POVERTY NEIGH-BOURHOODS

In 1981, there werejust four neighbour-hoods with ‘very high’poverty rates. Threeof them were located

in the old City of Toronto, in the RegentPark and the Kensington-Chinatownareas. The fourth was in the former Cityof Etobicoke, in the Mount Olive-Silverstone-Jamestown community.

By 2001, there were 23 ‘very high’ pover-ty neighbourhoods.1 While the number

CONCENTRATION OF POVERTY(%)

POVERTY RATE(%)

1981 1991 2001 1981 1991 2001

NEW CITY OF TORONTO 17.8 29.7 43.2 13.3 16.3 19.4

FORMER MUNICIPALITIES OF:

TORONTO 26.2 46.3 40.2 18.5 19.1 17.6

ETOBICOKE 7.7 18.6 35.3 9.6 12.3 15.3

YORK 12.4 23.0 48.5 15.9 19.9 22.1

NORTH YORK 18.8 25.0 48.9 13.3 16.4 22.0

SCARBOROUGH 13.9 25.0 39.8 11.2 15.4 20.3

EAST YORK – 10.6 52.1 11.3 13.8 19.7

CONCENTRATION OF FAMILY POVERTY & POVERTY RATE, CITY OFTORONTO AND FORMER MUNICIPALITIES

TABLE 8

Source: Statistics Canada - Census 1981, 1991 and 2001

The increase in the number ofhigher poverty neighbourhoodshas been especially acute in the

inner suburbs, where theircombined total of high poverty

neighbourhoods rose from15 in 1981, to 92 in 2001.

27

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

Source: Statistics Canada - Census 1981, 1991 and 2001

in the old City of Torontoincreased from 3 to 7, the fargreater increase occurred in theinner suburbs. The former Cityof North York had 7 ‘very high’poverty neighbourhoods by2001, equalling the number inthe old City of Toronto.Scarborough had 5, Etobicoke3, and East York, 1 (Table 10).

The two neighbourhoods withthe highest rate of family povertyin 2001 are located in theRegent Park community in theold City of Toronto, with onehaving an extraordinary highfamily poverty rate of 72.8%. Asecond part of the same commu-nity has a 59.1% poverty rate(Table 11).

There were four more neigh-bourhoods in 2001 that hadmore than half of their familiesliving in poverty. Two of theseare in the former City of NorthYork – one in the FlemingdonPark community, with a familypoverty rate of 57.8%, and theother in the Glenfield-JaneHeights area, with a 50.1%poverty rate.

1981 1991 2001

CITY OF TORONTO 4 9 23

FORMER MUNICIPALITIES OF:

TORONTO 3 5 7

ETOBICOKE 1 0 3

YORK 0 0 0

NORTH YORK 0 2 7

SCARBOROUGH 0 2 5

EAST YORK 0 0 1

NUMBER OF ‘VERY HIGH’ POVERTY NEIGH-BOURHOODS

TABLE 10

1981 1991 2001

NEW CITY OF TORONTO 30 66 120

FORMER MUNICIPALITIES OF:

TORONTO 15 32 28

ETOBICOKE 2 5 10

YORK 2 6 12

NORTH YORK 7 12 36

SCARBOROUGH 4 10 26

EAST YORK 0 1 8

NUMBER OF HIGHER POVERTYNEIGHBOURHOODS IN INNER SUBURBS

TABLE 9

Source: Statistics Canada - Census 1981, 1991 and 2001

1 Table 11 lists the 23 neighbour-hoods with family poverty rates of40% or greater. There are six com-munities on the list that have twocensus tracts within them with pover-ty rates that are 40% or greater.

28

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

The former City of Scarborough alsohad two neighbourhoods where over halfof the families are living in poverty – onein the Oakridge community, at 57.1%and the other in the Morningside area,with a 50.9% poverty rate.

In the next pages of the report, each ofthe former municipalities are consideredseparately. Additional information aboutthe population growth in each of the for-mer municipalities, growth in the num-ber of economic families, and the growthin the number of ‘poor’ economic fami-lies are contained in Tables 1.5, 1.6 and1.7 in Appendix One.

29

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

COMMUNITY IN WHICHCENSUS TRACT ISLOCATED

POVERTYRATE

FORMERMUNICIPALITY

REGENT PARK 72.8% TORONTO

REGENT PARK 59.1% TORONTO

FLEMINGDON PARK 57.8% NORTH YORK

OAKRIDGE 57.1% SCARBOROUGH

MORNINGSIDE 50.9% SCARBOROUGH

GLENFIELD-JANE HEIGHTS 50.1% NORTH YORK

BLACK CREEK 49.0% NORTH YORK

MOSS PARK 48.8% TORONTO

BLACK CREEK 48.1% NORTH YORK

KENSINGTON-CHINATOWN 47.7% TORONTO

WOBURN 45.0% SCARBOROUGH

THORNCLIFFE PARK 44.3% EAST YORK

GLENFIELD-JANE HEIGHTS 43.3% NORTH YORK

NORTH ST. JAMESTOWN 43.0% TORONTO

MOUNT OLIVE-SILVERSTONE-JAMESTOWN

43.0% ETOBICOKE

UNIVERSITY 42.6% TORONTO

MOUNT OLIVE-SILVERSTONE-JAMESTOWN

42.6% ETOBICOKE

SCARBOROUGH VILLAGE 42.4% SCARBOROUGH

FLEMINGDON PARK 41.7% NORTH YORK

ISLINGTON-CITY CENTRE WEST 41.5% ETOBICOKE

SOUTH PARKDALE 40.9% TORONTO

OAKRIDGE 40.1% SCARBOROUGH

PARKWOODS-DONALDA 40.0% NORTH YORK

NEIGHBOURHOODS WITH ‘VERY HIGH’ POVERTYRATES IN 2001, RANKED BY POVERTY LEVEL

TABLE 11

Source: Statistics Canada - Census 2001

30

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

THE FORMER CITY OF TORONTO

The former City of Toronto is the eco-nomic and cultural centre of the city-region. Its downtown is a mix of corpo-rate head offices, cultural facilities andpublic institutions, including majorbanks, insurance companies, museums,art galleries, the-atres, sports centres,hospitals, universi-ties and colleges.Most of its residen-tial housing stock isbetween 75 and a100 years old. Theincome disparity between its rich andpoor households is greater than in anyother part of the country. The formercity has the largest and oldest publichousing community in the country, builtin the late 1940s and 1950s.

Between 1981 and 2001, the total popu-lation of the old City of Toronto grew by12.9%; economic families by 27.2%; and‘poor’ economic families by 21.2%.

The neighbourhood poverty data showthat the income polarity in the city con-tinues to widen. The former City ofToronto was the only one of the six for-mer municipalities to experience both anincrease in the number of ‘lower’ povertyneigh and ‘higher’ poverty neighbour-

hoods between 1981and 2001. Theincrease in ‘lower’poverty neighbour-hoods was likely dueto the condominiumbooms of the late1980s and the 1990sto the present time,

which added nearly 40,000 units, whichwas 43% of the total number built in theentire city during this period of time.1

The number of higher poverty neigh-bourhoods increased from 15 in 1981, to32 in 1991. While there was someimprovement in the subsequent tenyears, down to 28 in 2001, the number isstill almost double what it was in 1981.

In 1981, 26.2% of the former city’s‘poor’ families lived in higher povertyneighbourhoods – the highest concentra-tion of all the former cities (Table 8).

Although poverty con-centration increased to40.2% in 2001, threeother former municipali-ties surpassed these lev-els by 2001.

FORMER CITY OF TORONTO 1981 1991 2001

LOWER POVERTY (0-12.9%) 49 53 61

MODERATE POVERTY (13 -25.9%) 73 59 62

HIGH POVERTY (26 -39.9%) 12 27 21

VERY HIGH POVERTY (40% +) 3 5 7

NUMBER OF NEIGHBOURHOODS BY POVERTY STATUS

TABLE 12

There has been an increase in thenumber of both lower poverty,and higher poverty neighbour-

hoods in the former City ofToronto in the last twenty years.

1 Source: CMHC housing

starts data.

Source: Statistics Canada - Census 1981, 1991 and 2001

31

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

FORMER CITY OF TORONTO - POVERTY LEVEL BY NEIGHBOURHOOD

TorontoLow Poverty

1981

1991

2001

0 -12.9 %13.0 - 25.9 %26.0 - 39.9 %40.0 - 70.0%

0 -12.9 %13.0 - 25.9 %26.0 - 39.9 %40.0 - 65.0%

0 -12.9 %13.0 - 25.9 %26.0 - 39.9 %40.0 - 73.0%

(2001 BOUNDARIES)

32

POVERTY BY POSTAL CODE

THE FORMER CITY OF ETOBICOKE

The former City of Etobicoke is locatedin the western portion of the City ofToronto. It encompasses the formerlakeshore villages of Mimico, NewToronto and Long Branch in the southand the large industrial area of Rexdalein the north. Its cen-tral area is home tomiddle and upperincome families,while the northernand southern areashouse more modestincome families.

The total population of Etobicoke grewby 13.2% between 1981 and 2001, whileits economic family population increasedby 6.6%, and its ‘poor’ economic familiesby 70%.

Etobicoke experienced an intensificationof neighbourhood poverty over the twen-ty-year period, although it was not assevere as in other areas. In fact, by 2001,half of all census tracts in Etobicoke still

had poverty rates below the 1981 averagefamily rate.

The major change that took place inEtobicoke was in the number of neigh-bourhoods that moved from ‘lower’ to‘moderate’ poverty. There was also con-siderable growth in higher poverty, from