PostScript - British Journal of OphthalmologyThe diagnosis was of steatocystoma sim-plex (SS) of the...

Transcript of PostScript - British Journal of OphthalmologyThe diagnosis was of steatocystoma sim-plex (SS) of the...

PostScript..............................................................................................

Merkel cell carcinoma of theeyelid in association with chroniclymphocytic leukaemiaMerkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare skinneoplasm. Tang and Toker1 first describedMCC in 1978 and since then 19 cases inassociation with chronic lymphocytic leukae-mia (CLL) have been reported.2–5 To the best ofour knowledge, involvement of the eyelid byMCC has never been reported in the literaturein association with CLL.

Case reportAn 84 year old white man was referred withan 8 week history of a painless lump on hisright upper eyelid (Fig 1A). He was complain-ing of visual obscuration secondary to amechanical ptosis. Ophthalmic history wasunremarkable and specifically there were noprevious chalazions or trauma. On examina-tion a firm lesion of the right eyelid measur-ing 2 × 1 cm with overlying telangiectatic ves-sels and sparing of the eyelashes was noted(Fig 1A). Further ophthalmic examinationwas unremarkable. General examination didnot reveal any abnormalities.

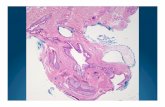

General medical history revealed that thepatient had been diagnosed with CLL 11months previously and was being treated withpulsed chlorambucil. His condition was con-sidered to be stable by his oncologist. At thetime he had a white cell count of 15.7 × 109/l.These consisted of immature lymphocytes of aB cell lineage. A full thickness incisionalbiopsy was performed under local anaesthe-sia. Histopathological examination of thebiopsy sample showed an intact epidermiswith the underlying dermis being infiltratedby clumps of a small cell tumour (Fig 2A).

Immunostaining showed the tumour cellswere negative for LCA (leucocyte commonantigen), CD3 (T cell marker), CD20 (B cellmarker), chromogranin, and S100 antigens.The tumour cells were positive for NSE (neu-ron specific enolase), EMA (epithelial mem-brane antigen) and CAM 5.2, which showedcharacteristic paranuclear accentuation (Fig2B). Other staining techniques showed 50% ofthe tumour cells to be in cycle. All thesefeatures are consistent with the diagnosis ofMCC.

Further investigation revealed no systemicmetastasis. We opted for radiotherapy as thepatient was reluctant to have surgical inter-vention. The patient was given a total of 40 Gyin 15 fractions. This caused the tumour toreduce in size relieving the mechanical ptosis(Fig 1B).

CommentThe recent surveillance, epidemiology, andend results (SEER) programme5 in the UnitedStates has estimated the incidence of MCC at0.23/100 000. MCC is very rare below the ageof 50 and is more common on sun exposedsites. It is an aggressive tumour with 12–45%being lymph node positive at presentation.This increases to 55–79% during the course ofthe disease. The 5 year survival has beenreported at 30–64%.6 7 Involvement of the eye-lid occurs in only 0.8% of MCC,5 and has notbeen reported in the literature in associationwith CLL.

Secondary tumours are common in B cellneoplasia with the relative risk of non-melanotic skin cancer being 4.7 in men and2.4 in women.8 The frequency and aggressive-ness of MCC and other skin neoplasmsincreases with immunosuppression, organ

transplantation, as well as B cell neoplasia.The precise reason for such an association isnot fully understood. Quaglino et al suggestedthat a depressed immunological system aswell as exogenous oncogenic factors may, invarious degrees, contribute to the develop-ment of neoplastic processes at differentsites.2

The treatment is wide local excision with orwithout adjuvant therapy consisting of blockdissection of lymph nodes or radiotherapy.Adjuvant therapy reduces local recurrenceand regional failure from 39% and 46% to 26%and 22% respectively.7 Most patients die fromcauses directly related to the disease.7 Poten-tially there is an increased risk of all skintumours including MCC in patients sufferingfrom CLL and this diagnosis should beconsidered when evaluating an eyelid lesionin such patients. In a patient with reducedimmunity it would be best practice to send allsurgical specimens for histology even if a sim-ple chalazion is thought to be responsible forthe lid lesion.

N Sinclair, K Mireskandari, J ForbesDepartment of Ophthalmology, Royal Free

Hampstead NHS Trust, London, UK

J CrowDepartment of Histopathology, Royal Free and

University College Medical School, London, UK

Correspondence to: Dr Sinclair;[email protected]

Accepted for publication 13 May 2002

References1 Tang C, Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of

the skin: an ultrastructural study. Cancer1978;42:2311–21.

2 Quaglino D, DiLeonardo G, Lallig.Association between chronic lymphocyticleukaemia and secondary tumours: unusualoccurrence of a neuroendocrine (Merkell cell)carcinoma. European Review for Medical andPharmacological Sciences 1997;1:11–16.

3 Ziprin P, Smith S, Salerno G, et al. Two casesof Merkel cell tumour arising in patients withchronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol2000;142:525–28.

4 Safadi R, Pappo O, Okon E, et al. Merkel celltumor in a woman with chronic lymphocyticleukaemia. Leukaemia and Lymphoma1996;20:509–11.

5 Miller RW, Rabkin CS. Merkel cell carcinomaand melanoma: etiological similarities anddifferences. Cancer Epidemology, Biomarkersand Prevention 1999;8:153–8.

6 Shaw J, Rumball E. Merkel cell tumour:clinical behaviour and treatment. Br J Surg1991;78:138–42.

7 Hamilton J, Levine M, Lash R, et al. Merkelcell carcinoma of the eyelid. Surg Rev1993;24:764–9.

8 Mellemgaard A, Geisler CH, Storm HH. Riskof kidney cancer and other second solidmalignancies in patients with chroniclymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Haematol1994;53:218–22.

Steatocystoma simplex of thecaruncleThe caruncle has a non-keratinised epitheliallining similar to the conjunctival epithelium.However, unlike the conjunctiva, the caruncleharbours skin elements such as hair follicles,sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and accessory

Figure 1 (A) Merkel cell tumour involving most of the upper lid causing mechanical ptosisand visual obscuration. Biopsy site is seen laterally. (B) Merkel cell tumour after treatment withradiotherapy.

Figure 2 (A) Haematoxylin and eosin stain Merkel cell tumour. (B) Immunostaining withCAM5.2 showing characteristic para-nuclear accentuation.

Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:240–251240

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

lacrimal tissue. Consequently, the carunclemay develop a tumour or cyst similar to onefound in the skin, conjunctiva, or lacrimalgland.

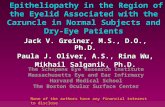

Case reportA 26 year old woman presented with a 2 mm,asymptomatic, pale yellow lesion of the rightcaruncle, present for 8 months (Fig 1). It wasexcised intact under local anaesthetic andhistological examination revealed a cyst linedby stratified squamous epithelium and con-taining sebaceous glands in its wall (Fig 2).These communicated directly with the cystlumen. No associated hair follicles were seen.An eosinophilic, crenulated cuticle waspresent on the inner aspect of the cyst wall insome areas. The patient had no other skinlesions of note. The nails, teeth and hair werenormal. There was no family history of similarlesions. At the 6 month follow up there havebeen no signs of recurrence or development ofother cysts.

The diagnosis was of steatocystoma sim-plex (SS) of the caruncle.

CommentSteatocystoma simplex, the non-heritablesolitary counterpart of steatocystoma multi-plex (SM), was first described as a distinctentity by Brownstein in 1982.1 It is a benign

adnexal tumour, thought to originate from anaevoid malformation of the pilosebaceousduct junction.2

Lesions are described on the forehead, nose,scalp, neck, axillae, chest, upper limbs, back,legs,1 and even intraorally.3 To our knowledgethough, steatocystoma has not previouslybeen reported in the caruncle.4 5

Thirty two cases of SS are reported in theliterature, divided evenly between men andwomen and ranging in age from 15 to 70years.1 3 6 Clinical and histological features inSS are usually identical to those seen in theindividual lesions of SM. Lesions are de-scribed as asymptomatic, flesh coloured oryellowish, intracutaneous, well circum-scribed, soft, mobile, and non-tender. On inci-sion they are found to contain an oilysubstance composed of sebum.1

However, it is important to confirm thesolitary nature of a steatocystoma. SM can befamilial and autosomal dominantly inherited(steatocystoma multiplex congenita).7 Severalfamilial cases have been linked to pachy-onichia congenita and ectodermal dysplasiathrough a mutation in keratin 17.8 It has beenassociated with hypothyroidism, hypohidro-sis, hypotrichosis and hypertrophic lichenplanus, ichthyosis, and koilonychia.9 SM maybe progressive with inflamed cysts, rupturing,and healing with scars.7

Steatocystoma is histologically character-ised by a cystic structure with sebaceousglands within the cyst wall and epitheliumthat displays an eosinophilic cuticle. It is pos-sible to make a diagnosis of steatocystoma ifthe characteristic hyaline luminal cuticle ispresent, even in the absence of sebaceouselements.1

The differential diagnosis included seba-ceous gland hyperplasia, sebaceous glandadenoma, and lipogranuloma. Clinically theyare also characterised by a yellow, nodularappearance.5 Rarely, sebaceous gland carci-noma of the caruncle may occur.5 Along withhidrocystoma and eruptive vellus hair cystthey can usually be excluded histologically.Oncocytomas are asymptomatic, slowly pro-gressive, solid or cystic masses but usuallydescribed as reddish blue/tan.4 5

Most treatment regimens for steatocystomareflect the multiplicity and widespread extentof lesions of SM. Oral isotretinoin has beenused to reduce associated inflammation.Cryosurgery, carbon dioxide laser, and inci-sion with removal of the cyst wall have beenemployed.7 10 We felt the best way to managethis solitary lesion arising in the caruncle wasby simple excision with removal of the cystwall intact, thereby reducing the risk of recur-rence. We were able to confirm the uniquenature of this lesion and rule out malignancy.

J Bowyer, T SullivanThe Eyelid, Lacrimal and Orbital Clinic, Division of

Ophthalmology, Department of Surgery, RoyalBrisbane Hospital, Herston Road, Herston,

Brisbane, Qld, 4029, Australia

K WhiteheadSullivan Nicolaides and Partners, 134 Whitmore

Street, Taringa, Qld, 4068, Australia

Correspondence to: Dr T Sullivan; [email protected]

Accepted for publication 24 June 2002

References1 Brownstein MH. Steatocystoma simplex; a

solitary steatocystoma. Arch Dermatol1982;118:409–11.

2 Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Follicular hybridcysts; an expanded spectrum. Am JDermatopathol 1991;13:228–33.

3 Olson DB, Mostofi RS, Lagrotteria LB.Steatocystoma simplex in the oral cavity: apreviously undescribed condition. OralSurgery Oral Med Oral Pathol1988;66:605–7.

4 Luthra CL, Doxanas MT, Green WR. Lesionsof the caruncle. A clinicopathological study.Surv Ophthalmol 1978;23:183.

5 Shields CL, Shields JA, White D, et al. Typesand frequency of lesions of the caruncle. Am JOphthalmol 1986;102:7721–8.

6 Nakamura S, Nakayama K, Hoshi K, et al.A case of steatocystoma simplex on the head.J Dermatol 1988;15:347–8.

7 Pamoukian VN, Westreich M. Fivegenerations with steatocystoma multiplexcongenita: a treatment regimen. PlasticReconstruct Surg 1997;99:1142–6.

8 Feinstein A, Friedman J, Schewach-Millet M.Pachyonychia congenita. J Am Acad Dermatol1988;19:705–11.

9 Sohn D, Chin TCM, Fellner MJ. Multiplekeratoacanthomas associated withsteatocystoma multiplex and rheumatoidarthritis. Arch Dermatol 1980;116:913–4.

10 Krahenbuhl A, Eichmann A, Pfaltz M. CO2

laser therapy for steatocystoma multiplex.Dermatologica 1991;183:294–6.

Preliminary results with posteriorlamellar keratoplasty forendothelial failureWe describe the technique and the results ofthree cases where we performed a posteriorlamellar keratoplasty.

Case reportsThe following surgical technique was per-formed in all cases. The donor posteriorbutton was obtained from an entire freshglobe. We made sure that intraocular pressurewas adequate by injecting BSS (balanced saltsolution, Alcon) in the vitreous cavity. With aMoria ONE microkeratome, an anterior cap of250 µm was cut and lifted. A Barron trephine7 mm in diameter was used to obtain the pos-terior button, covered afterwards with visco-elastic to protect it and to avoid desiccation.

With our microkeratome an 8.5 mm indiameter, nasal hinge and 250 µm flap wasobtained. The trephination was made with a 7mm Barron trephine and completed with cor-neal scissors, under viscoelastic protection.

After the intraocular injection of acetylcho-line the posterior donor button was placed onthe recipient eye under viscoelastic protection.Six 10-0 Nylon interrupted sutures were usedto secure and close the wound. Immediatelyafter, the flap was put back and fixated withsix interrupted 10-0 Nylon sutures and theknots were buried. The viscoelastic anteriorchamber was exchanged with BSS using anautomatic pressure controlled irrigation-aspiration system.

Case 1This was a 36 year old woman with Fuchs’endothelial dystrophy. Preoperative BSCVAwas 0.4 in the right eye and 0.6 in the left. Slitlamp examination showed diffuse cornealoedema clearly affecting the anterior layers ofthe cornea. Endothelial cell count (ECC) wasbelow 900 cells/mm in both eyes. Surgery wasperformed on the right eye (Fig 1A). The fol-low up was done for 12 months (Fig 1B).

Case 2Case 2 was a 57 year old man with Fuchs’endothelial dystrophy. Preoperative BSCVAwas 0.1 in the right eye and 0.06 in the left.Slit lamp examination showed diffuse stromalcorneal oedema in the left surgical eye. ECCswere difficult to perform because of the light

Figure 1 Clinical appearance of the paleyellow lesion of the right caruncle (arrowed).

Figure 2 Histological examination revealsa cyst, lined by stratified squamousepithelium with an eosinophilic cuticle on theinner aspect (C) and sebaceous glands in thecyst wall communicating directly with thelumen (SG). The diagnosis is steatocystoma.(Original magnification ×100, haematoxylinand eosin.)

PostScript 241

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

scattering induced by the oedema but werebelow 800 cell/mm in both eyes. The patient’scase was followed for 12 months (Fig 1C)

Case 3This was a 57 year old man with history ofmyopia in both eyes (right eye −4.00, left eye−9.00). There was a history of subretinalmacular neovascularisation and cataract ex-traction in his left, surgical, eye, with an ECCof 950 cell/mm. Preoperative BSCVA was 0.5 inthe right eye and 0.2 in the left. The follow upwas done during 14 months (Fig 1D).

Examinations in all cases were at day 1, 1week, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. All Nylon sutureswere removed before the 6 month control.

All surgeries were technically uneventful.The immediate and late postoperative controlsshowed transparency of the cornea and nosigns of rejection. In case 1 at the time ofremoving the superior suture (3 months post-operatively) a separation between the anteriorcap and the edge of the corneal recipient eye

was observed (because of the stromal flapoedema) and two interrupted 10–0 Nylonsuture were placed for 3 more months.

Uncorrected and BSCVA did not improve inall cases in spite of corneal transparency(Table 1). We observed a significant increase inastigmatism in all cases during the follow upand also after the suture removal,1 but it wasnot the main cause of reduced vision (Table 2).We checked vision changes with refractionover rigid gas permeable lenses but the resultswere lower than expected.

CommentMany attempts have been made to independ-ently replace the endothelial layer. FirstMohay2 and McCulley3 used eyes of theanimal models and obtained successful re-sults. Later, Melles et al described a surgicaltechnique in which through a scleral tunnelincision a mid-stromal pocket was dissectedto separate and transplant the posteriorstroma4 Ehlers5 and Busin,6 using a micro-keratome to access the posterior cornea, also

had similar results. We used the open tech-

nique as described by Busin, but suturing

both corneal layers, and our cases showed a

significant astigmatism and very low visual

results.

Reviewing our experience during the past 6

years in performing penetrating keratoplasty

(PK) for Fuchs’s dystrophy, and obviously

understanding that this is not a comparative

study, we realised that our mean improvement

in best corrected visual acuity was 3.1 lines

(range 0–8), with a mean postoperative time

for visual rehabilitation of 8 months (range

3–18 months).

The recovery time was slower when com-

pared with PK, perhaps because of the optical

distortion of the interface. We must also not

forget that we sutured both the donor button

and the superficial lenticule, perhaps inducing

interface distortion. Also it is important to

mention the risk of wound leakage and inter-

face aqueous humour dissection.

We think that the time of graft deswelling

was not as expected because at the time of

suture removal a separation was noted be-

tween the anterior cap and the recipient eye in

cases 1 and 2. We placed sutures in this site

but the time of suture removal was extended

to 12 months. Another contributing factors

would be host-graft disparity, trephination,

and suture technique.5

In our experience this technique shows that

it is possible to change only the posterior lay-

ers of the cornea with successful anatomical

result. Nevertheless, from a functional per-

spective penetrating keratoplasty has been a

much better and faster approach and, in fact,

in both techniques we are replacing the

endothelium using an open sky technique.

J L. Güell, F Velasco, E Guerrero, O GrisCornea and Refractive Surgery Department,

“Instituto de Microcirugía Ocular,” Barcelona,Spain

M CalatayudCornea and Refractive Surgery Unit, University

Hospital, Vall d’ Hebron, Barcelona, Spain

Correspondence to: Jose L Güell, MD, PhD, Institutode Microcirugía Ocular, Departamento de Cornea,

c/Munner 10, 10 CP 08022, Barcelona Spain;[email protected]

Accepted for publication 17 July 2002

Figure 1 (A) Photography of case 1 at 1 week after posterior lamellar keratoplasty. (B) Case1 at 12 months after posterior lamellar keratoplasty. (C) Case 2 at 3 months after posteriorlamellar keratoplasty.(D) Case 3 at 6 months after posterior lamellar keratoplasty.

Table 1 Best corrected visual acuity before and after the endokeratoplasty

Preoperative 2 Weeks 3 Months 6 Months 9 Months 12 Months

Case 1 0.5 Counting fingers to 1metre

0.1 0.1 0.32 0.5

Case 2 0.63 0.1 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.5Case 3 Counting fingers 0.5

metreCounting fingers 0.5metre

Counting fingers 0.5metre

Movements of hands0.5 metre

Movements of hands0.5 metre

Movements of hands0.5 metre

Table 2 Astigmatism before and after of endokeratoplasty

Preoperative 2 weeks 3 months 6 months 9 months 12 months

Case 1 −0.75 −7.00 −7.50 −8.50 −9.50 −6.00Case 2 −2.00 −3.00 −4.00 −5.00 −6.50 −5.00Case 3 −0.5 −3.00 −4.00 −4.00 −3.50 −3.50

242 PostScript

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

References1 Pineros O, Cohen EJ, Rapuano CJ, et al.

Long-term results after penetrating keratoplastyfor Fuch’s endothelial dystrophy. ArchOphthalmol 1996;114:15–18.

2 Mohay J, Lange T, Soltau J, et al.Transplantation of corneal endothelial cellsusing a cell carriers device. Cornea1994;13:173–82.

3 McCulley JP, Maurice DM, Schwartz BD,Corneal endothelium transplantation.Ophthalmology 1980;87:194–201.

4 Melles G, Lander F, Beekhuis W, et al.Posterior lamellar keratoplasty for a case ofpseudophakic bullous keratopathy. Am JOphthalmol 1999;127:340–1.

5 Ehlers K, Ehlers H, Hjortdal J, et al. Graftingof the posterior cornea. Description of a newtechnique with 12-month clinical results. ActaOphthalmol Scand 2000;78:543–6.

6 Busin M, Arffa R, Sebastián A.Endokeratoplasty as an alternative topenetrating keratoplasty for the surgicaltreatment. Ophthalmology 2000;107:2077–82.

Persistent accommodative spasmafter severe head traumaSpasm of accommodation is the suddendevelopment of a considerable degree of myo-pia which disappears after cycloplegia, usuallyfunctional in origin.1 Bohlmann and France2

reported a patient with persistent spasm ofaccommodation 9 years after head traumaand suggested that a possible lesion in theupper brainstem might be responsible for thedysfunction. We report two similar cases inwhich magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)failed to show abnormalities in the mid-brainand revealed cerebellar and supratentorialtraumatic lesions.

Case reportsCase 1A 34 year old female patient came to therefractive surgery service for correction ofmyopia and astigmatism. She had been coma-tose for 45 days after suffering severe headinjury at the age of 24, and 3 months laternoticed difficulties in her distant vision andwas prescribed corrective lenses.

Dynamic refraction revealed in the right eye−3.75 sph −1.50 cyl × 5 and in the left eye−3.50 sph −1.00 cyl × 170. Visual acuity was20/25 in each eye with this correction. Pupils

were equal in size and measured 5 mm innormal room light, with normal reactions.Cycloplegic refraction after instillation of twodrops of 1% cyclopentolate and one drop of 1%tropicamide revealed −1.25 sph −1.50 cyl × 5right eye and −0.75 sph −1.25 cyl × 165 lefteye, obtaining 20/20 in each eye. She hadattention and memory deficits, left cerebellarataxia, left pyramidal syndrome, and speechdifficulties due to vocal cord paresis. The MRIscan showed multiple lesions in the peri-ventricular and subcortical white matterinvolving the left temporal lobe (Fig 1) and inthe frontal and parieto-occipital regions bilat-erally on FLAIR sequences. High signal inten-sity was observed in the cerebellar vermis aswell as in the dorsal pons (Fig 1). Noabnormalities was observed in the mid-brain.Images with 3 mm thickness T2 weightedspin echo sequences also did not revealabnormalities in the mid-brain (Fig 2).

The cycloplegic refraction was prescribedbut she returned 2 months later complainingof blurred vision. She was prescribed −2.50sph −1.50 cyl × 5 right eye and −2.00 sph −1.25

cyl × 165 left eye which she has been wearingfor 6 years, despite still having difficultieswith distance vision. Multiple repeat exami-nations confirm that she needs −1.25 sph overher glasses in order to reach 20/20 vision ineach eye. Cycloplegic refraction remain un-changed from the first examination.

Case 2A 24 year old male patient had blurred distantvision soon after he recovered from headinjury including a 2 months period in a coma.He had not worn glasses in the past.

On examination visual acuity was 20/200both eyes without correction and 20/25 with−3.00 sph in each eye. Pupils measured 4 mmeach with normal reactions. The rest of theophthalmic examination was normal. Cy-cloplegic refraction, after instillation of twodrops of 1% cyclopentolate and one drop of 1%tropicamide, revealed 20/20 vision both eyes(+0.25 sph in each eye). He had recentmemory and gait deficits. MRI scan revealed aheterogeneous area, hypointense on T1 andhyperintense on T2 weighted images, affect-ing the left temporal lobe, compatible withgliotic reaction. There were no abnormalitiesin the dorsal mid-brain.

The patient was prescribed 1% atropineevery 12 hours, which he took for 6 monthswith normal distance vision but he com-plained of difficulties reading and photopho-bia. Atropine was discontinued and blurreddistant vision recurred. He then took atropineevery other day for 2.5 years associated withreading glasses. When it was discontinuedhowever, accommodative spasm again re-curred and a −3.00 sph correction in both eyeswas prescribed.

CommentIn our patients, a relation of accommodativespasm and the head trauma seems well estab-lished because it appeared soon after theyhave recovered from severe head injury,persisted for several years despite the pro-longed use of cycloplegic drops, and thepatients were not trying to obtain any benefitby complaining of blurred vision.

The supranuclear control of accommoda-tion is poorly understood. In cats, neuronsthat discharge in temporal correlation withaccommodation were found in the lateralsuprasylvian area.3 Electrical stimulation onipsilateral interpositus nuclei and on contra-lateral interpositus and fastigial nuclei in thecerebellum are known to induce accommoda-tion.4 These nuclei are connected to parasym-pathetic oculomotor neurons in the mid-brain.3 4

Very little accommodative dysfunction re-sulting from central lesions has been reportedin humans. Ohtsuka et al5 studied a patientwith left middle cerebral artery occlusion whohad reduced accommodative responses andmarkedly lowered accommodation velocity.Their patient had low density lesions on com-puted tomograph (CT) scan involving the lefttemporal lobe, near the sylvian fissure. Kawa-saki et al6 reported a patient with normalaccommodation amplitude but increased ac-commodation and relaxation times. Theirpatient recovered normal accommodation 10days after removal of a large subtentorialarachnoid cyst and the authors suggested thatthe cerebellum might have a role in theorganisation of the human central controlsystem of accommodation.

Bohlmann and France described a patientwith persistent spasm of accommodationafter head trauma.2 CT scan revealed a skullbase fracture without intracranial abnormali-ties and the authors suggested that a possible

Figure 1 Case 1. Magnetic resonance imaging FLAIR sequences (TR 8000, TE 150, TI2300 ms) magnetic resonance imaging scan (6 mm thickness) showing white matter lesion inthe temporal lobe (black arrows), in the dorsal pons (small white arrow), and in the cerebellarvermis (large white arrow). Cerebellar atrophy is indicated by enlarged folia.

Figure 2 Case 1. T2 weighted (TR 3570,TE 120 ms) spin echo sequences, 3 mmthickness, with normal findings in themid-brain.

PostScript 243

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

mesencephalic lesion might be responsible forthe spasm. Chan and Trobe7 reported aretrospective review of six patients with post-traumatic pseudomyopia but did not includeMRI studies. In our patients, MRI scan failedto show abnormalities in the mid-brain. Bothof them had lesions in the left temporal lobeand the first patient also had abnormalities inthe frontal and parieto-occipital lobes bilater-ally and the cerebellum. Although it ispossible that they have small mesencephaliclesions, not detected by MRI scan, thefindings is our cases suggest a higher originfor accommodative dysfunction in some pa-tients with closed head trauma.

M L R MonteiroDepartment of Ophthalmology, Hospital das

Clínicas of the University of Sao Paulo MedicalSchool, Sao Paulo, Brazil

A L L CuriDepartment of Ophthalmology, Fluminense Federal

University, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

A PereiraDepartment of Ophthalmology, Hospital das

Clínicas of the University of Sao Paulo MedicalSchool, Sao Paulo, Brazil

W ChamonDepartment of Ophthalmology, Sao Paulo Federal

University, Sao Paulo, Brazil

C C LeiteDepartment of Radiology, Hospital das Clínicas of

the University of Sao Paulo Medical School, SaoPaulo, Brazil

Correspondence to: Mário L R Monteiro, MD, AvAngélica 1757 conj.61, 01227–200, Sao Paulo,

SP, Brazil; mlrmonteiro@ terra.com.br

Accepted for publication 18 July 2002

References1 Goldstein JH, Schneekloth BB. Spasm of the

near reflex: a spectrum of anomalies. SurvOphthalmol 1996;40:269–78.

2 Bohlmann BJ, France TD. Persistentaccommodative spasm nine years after headtrauma. J Clin Neuro-ophthalmol1987;7:129–34.

3 Bando T, Yamamoto N, Tsukahara N.Cortical neurons related to lensaccommodation in posterior lateralsuprasylvian area in cats. J Neurophysiol1984;52:879–91.

4 Hosoba M, Bando T, Tsukahara N. Thecerebellar control of accommodation of theeye in the cat. Brain Res 1978;153:495–505.

5 Ohthsuka K, Maekawa H, Takeda M, et al.Accommodation and convergenceinsufficiency with left middle cerebral arteryocclusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;106:60–4.

6 Kawasaki T, Kiyosawa M, Fujino T, et al.Slow accommodation release with acerebellar lesion. Br J Ophthalmol1993;77:678.

7 Chan RVP, Trobe JD. Spasm ofaccommodation associated with closed headtrauma. J Neuro-Ophthalmol 2002;22:15–17.

Extramedullary plasmacytoma ofthe eyelidA 74 year old man presented with a foreignbody sensation in the right eye superimposedon a slowly growing enlarging lump in theright eyelid. He had no history of recurrentinfections, bleeding, weight loss, or nightsweats. His only other symptom was chronicbackache secondary to osteoarthritis. Pastmedical history included cataract extractionfrom the right eye 4 years previously andexcision of a basal cell carcinoma from theright pinna 5 years previously. Examination

revealed a large firm lesion in the right uppereyelid with no palpable lymph nodes. Theclinical diagnosis was of a chalazion.

The lesion was removed surgically andhistopathology (Fig 1) revealed an incom-pletely excised extramedullary plasmacytomawith a high proliferative index and amyloidchange. Immunocytochemistry was positivefor IgG kappa light chains. Further investiga-tions including full blood count, liver functiontests including lactate dehydrogenase (LDH),protein electrophoresis, skeletal survey, andbone marrow aspiration were normal with noevidence of multiple myeloma.

The whole of the upper eyelid was treatedwith radiotherapy using a customised leadcutout with internal shielding of the eye (Fig2); 120 kV x rays were used giving a dose of 30Gy in 10 fractions over 2 weeks.

On follow up (at 2 years) there has been noevidence of local recurrence or the develop-ment of myeloma, and lacrimation in the eyeappears normal.

CommentSolitary plasmacytomas are rare tumours.They are classified as either solitary plasmacy-tomas of bone (SPB) or extramedullaryplasmacytomas (EMP) of soft tissue. Themajority of EMPs (about 80%) involve theupper air passages of the head and arethought to arise in the submucosa, whereplasma cells are numerous.3 4 Other sitesinclude lymph nodes, spleen, skin and sub-cutaneous tissues, gastrointestinal tract, thy-roid, and testes.

There is a relation between solitary plasma-cytomas and subsequent development ofmultiple myeloma. About 44–69% of patientswith a solitary bone plasmacytoma willdevelop multiple myeloma within a mediantime of 3 years.5 Although EMPs recur inalmost 50% of cases, this is usually in bone butunlike multiple myeloma it remains circum-scribed within the bone with no predilection

for the axial skeleton. However, progression tomyeloma does occur though at a lower ratethan for SPB. Alexiou et al4 reported a rate ofprogression to myeloma for both upperaerodigestive tract and non-aerodigestivetract extramedullary soft tissue plasmacyto-mas of 16.1% and 14.6% respectively. As nopredictors of progression have been identifiedpatients probably need indefinite follow up.

Eye abnormalities such as cysts of theciliary body and vascular lesions have beendescribed in multiple myeloma but primaryplasmacytoma involving the eye is rare. Nine-teen cases affecting the orbit have beendescribed in the literature but this is only thefourth case of a primary plasmacytomaarising from the eyelid that has been reported.Most of the earlier reports of the plasmacyto-mas arising in the eye are not true plasmacy-tomas and are in fact granulomas due tochronic inflammation.7 Usual symptoms areprogressive painless swelling of the eyelid,proptosis, and diplopia. They can occur at anyage but the mean age of onset is in the sixth toseventh decade. The youngest reported casewas that of an 11 year old who had plasmacy-toma of the orbit.8

Of the three previously reported cases, allwere treated with surgical excision.7 9 10 Theirimmunocytochemistry was IgG lambdachain, kappa light chain, and IgG lambdachain respectively. Our case is similar but wastreated successfully with radiotherapy afterincomplete excision.

Solitary extramedullary plasmacytomascan be controlled with radiotherapy alone.Response rates with radiotherapy are as highas 94% and 93% for SPB and EMPrespectively.11 The optimal dose of radio-therapy has not been defined, though itappears that a dose of at least 30 Gy isrequired. Many centres use doses of between40–50 Gy.3 The extent of radiotherapy portalsis also a subject of debate with manyrecommending inclusion of regional lymphnodes if possible. The median survival ofpatients with EMP treated with radiotherapywas 8.5 years in one study with most patientsdying of causes unrelated to their EMP.12

Surgery is also an option, with Alexiou etal4 reporting a lower rate of progression tomyeloma for those treated by surgery (6.3%)compared with those treated with radiation(17.5%). The conversion rate for patientstreated with both modalities was 13.5%. Theseresults may reflect differences in the size oflesions, with small extramedullary plasmacy-tomas in easily accessible sites being amena-ble to surgical excision.

Chemotherapy is used for those patientswho progress to multiple myeloma.

E Ahamed, L M Samuel, J E TigheANCHOR Unit, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary,

Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZN, UK

Correspondence to: Dr L M Samuel, ANCHOR Unit,Ward 17, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Foresterhill,

Aberdeen AB25 2ZN, UK;[email protected]

Accepted for publication 22 July 2002

References1 Woodruff RK, Whittle JM, Malpas JS.

Solitary plasmacytoma. I Extramedullary softtissue plasmocytoma. Cancer1979;43:2340–3.

2 Uceda-Montanes A, Blanco G, Saornil MA,et al. extramedullary plasmacytoma of theorbit. Acta Ophthalmol Scand2000;78:601–3.

3 Selby P, Gore M. Myeloma and other plasmacell malignancies. Oxford Textbook ofOncology. Vol 2 .1995;12:81852–78.

Figure 1 Photomicrograph showinginfiltration of the conjunctiva by theneoplastic plasma cells with strongimmunocytochemical staining forimmunoglobulin IgG (×355).

Figure 2 Whole of upper eyelid treated byradiotherapy using a customised lead cutoutwith internal shielding of the eye.

244 PostScript

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

4 Alexiou C, Kan RJ, Dietzfelbinger H, et al.Extramedullary plasmacytoma. Cancer1999;85:2305–14.

5 Dimopoulos MA, Goldstein J, Fuller L, et alcurability of solitary bone plasmacytoma. JClin Oncol 1992;10:587–90.

6 Ganjoo RK, Malpas JS. Plasmacytoma,myeloma:biology and management. NewYork 1995;463–76.

7 Seddon JM, Corwin JM, Weiter JJ, et alSolitary extramedullary plasmacytoma of thepalpebral conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol1982;66:450–4.

8 Sharma MC, Mahapatra AK, Gaikwad J, etal. Primary extramedullary orbitalplasmacytoma in a child. Childs NervousSystem 1996;12:470–2.

9 Olivieri L, Ianni MD, Giansanti M, et al.Primary eyelid plasmacytoma. Med Oncol2000;17:74–5.

10 Choi WJ, Tchah H, Kim YJ. Plasmacytomapresented as a lid mass. Korean J Ophthalmol1991;5:92–5.

11 Holland J, Trenkner DA, Wasserman TH, etal. Plasmacytoma—treatment results andconversion to myeloma. Cancer1992;69:1513–17.

12 Knowling MA, Harwood AR, Bergsagel DE.Comparison of EMPs with solitary and multipletumours of the bone. J Clin Oncol1983;1:255–62.

Idiopathic sclerochoroidalcalcificationSclerochoroidal calcification is a relatively rarecondition characterised by yellow-whiteirregular subretinal lesions usually in thesuperotemporal mid-periphery of the fundus.It is usually asymptomatic and has a classicclinical appearance. Most cases are idiopathicbut a few reports have associated thiscondition with abnormalities of electrolytes.1–3

We present three cases of idiopathic sclero-choroidal calcification.

Case reportsCase 1A 71 year old white woman was referred byher optician after attending for routine glassesupdate. On questioning she did complain of a“slight blurring of vision” gradually forseveral months. She had a history of leftamblyopia. Her medical history includedasthma, osteoarthritis, lymphoedema, fibro-myalgia, and hiatus hernia. Her only medica-tions were inhalers and paracetamol. She hadpreviously taken calcium supplements. Hervisual acuities were 6/6 in the right eye and6/12 in the left eye with a hypermetropic cor-rection. She had early cortical lens opacitiesand no vitritis. Both fundi revealed minimallyelevated yellow areas in the choroid along thesuperotemporal arcades (Fig 1A).

The patient had haematological investiga-tions revealing a normal full blood picture,urea and electrolytes, ACE level, urate, liverfunction tests, bone profile, immunoglobu-lins, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR),and C reactive protein. She also had a chest xray which was unremarkable. Her fundalphotography showed autofluorescence ofthese lesions and ultrasound scanning aidedthe diagnosis in that the lesions were highlyreflective with orbital shadowing (Fig 1B).

Case 2An 82 year old white woman was referred byher optician complaining of a gradual reduc-tion in vision bilaterally. She had recentlybeen diagnosed with polymyalgia rheumaticaand was well controlled with oral pred-nisolone. She had no headaches. Her medicalhistory included oesophagitis and hiatus her-nia and cervical spondylosis. Her unaided

visual acuity was 6/12 right eye improving to6/9 with pinhole, and 6/18 left eye improvingto 6/12 with pinhole. She had bilateralnucleosclerotic cataracts and both fundi re-vealed numerous pale elevated lesions clus-tered around the superotemporal and infero-temporal arcades (Fig 2A).

Haematological investigations and chest xray were unremarkable. Ultrasound scanningrevealed that these were areas of calcificationwith high reflectivity (Fig 2B).

Case 3A 71 year old man attended routinely forreview 2 weeks after cataract extraction. Hehad no past medical history and vision was6/9 right eye and 6/6 left eye. He was noted tohave a small optic disc haemorrhage coinci-dentally and therefore dilated fundal exam-ination was performed. He had bilateral pale

yellow elevated lesions along the superotem-poral arcades and also nasally in both fundi.Again electrolytes were investigated and werewithin the normal range.

CommentSclerochoroidal calcification has been de-scribed in the literature as an uncommoncondition found usually in older whitepatients.3 Patients have been unnecessarilyinvestigated in the past and even treated fortumours unnecessarily.4 Calcification can bedystrophic or metastatic but in these idio-pathic cases it is the former. The calcificationis believed to be deposited at the sites ofinsertions of the oblique extraocular musclesin a similar way that Cogan scleral plaques arecalcification at the insertions of the horizontalrecti muscles.5 Reports have been made ofsclerochoroidal calcification associated withBartter syndrome,1 Gitelman syndrome,2 hy-perparathyroidism, and hypomagnesaemia.3

It is important to exclude any electrolyteabnormality when a patient presents with thiscondition, but prolonged investigations areunnecessary. Autofluorescence and ultra-sound appearances are very useful to diagnosethis condition. Patients rarely develop visualdisturbance with sclerochoroidal calcification,but infrequent follow up is advised as cases ofassociated choroidal neovascular membranesand serous detachments with the lesions havebeen documented.6

AcknowledgementsALCON kindly sponsored the publication costs of the

figures.

C A Cooke, C McAvoy, R BestDepartment of Ophthalmology, Royal Victoria

Hospital, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK

Correspondence to: Dr Carole A Cooke

Accepted for publication 29 July 2002

References1 Marchini G, Tosi R, Parolini B, et al.

Choroidal calcification in Bartter syndrome.Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:727–9.

2 Bourcier T,Blain P, Massin P et al.Sclerochoroidal calcification associated withGitelman syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol1999;128:767–8.

3 Honavar SG, Shields CL, Demirci H, et al.Sclerochoroidal calcification. ArchOphthalmol 2001;119:833–40.

4 Lim JI, Goldberg MF. Idiopathicsclerochoroidal calcification. Arch Ophthalmol1989;107:1122–3.

Figure 1 Case 1 (A) Elevated yellow areas along the supertemporal arcades bilaterally anddemonstration of autofluorescence of these lesions. (B) Ultrasound scan showing the lesions tobe highly reflective with orbital shadowing.

Figure 2 Case 2 (A) Pale yellow elevatedlesions in the mid-periphery clustered aroundthe superotemporal arcade. (B) Ultrasound oflesions revealing that they are areas ofcalcification with high reflectivity.

PostScript 245

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

5 Cogan DG, Kuwabara T. Focal seniletranslucency of the sclera. Arch Ophthalmol1959; 62:604–10.

6 Leys A, Stalmans P, Blanckaert J.Sclerochoroidal calcification with choroidalneovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:854–7.

Stereotactic irradiation of biopsyproved optic nerve sheathmeningiomaThe role of conventional external beam radio-therapy in the management of optic nervesheath meningiomas (ONSM) has been con-troversial because of limited radiation sensi-tivity of these tumours and radiation damageto surrounding tissues.1 Recently, in a study of64 patients with ONSM managed with obser-vation, surgery, radiotherapy, or surgery andradiotherapy, Turbin and colleagues2 foundthat patients treated by (conventional) radio-therapy alone demonstrated the best longterm visual outcome, and suggested fraction-ated external beam radiation (5000–5500cGy) as the initial treatment in selected cases,when preservation of visual function is a rea-sonable goal.

The collateral damage secondary to conven-tional radiotherapy may be minimised by bet-ter focusing and shaping of the radiationbeams, as in stereotactic radiotherapy(SRT).3–5 We report on a woman whom wetreated with fractionated SRT for a biopsyproved, large ONSM.

In April 2000 a 41 year old woman wasreferred with a 1 month history of proptosis ofher left eye (Fig 1, top left). She had beentreated for a presumed orbital “pseudotu-mour” with oral prednisone (initial dose 90mg/day) without effect.

At referral, she had no history of diplopia orretrobulbar pain. On examination, the visualacuity (VA) was 1.25 (unaided) of the righteye and 0.8+ (cc S+2) of the left eye. Theintraocular pressure was 18 and 21 mm Hg inthe right eye and left eye, respectively. Therewas a left relative afferent pupillary defect(RAPD). The motility of the left eye wasslightly restricted in upgaze. The left eyeshowed mild periocular swelling and conjunc-tival chemosis. There was 5 mm of leftproptosis without upper eyelid retraction orlid lag. Funduscopy of both eyes showed noabnormalities. Visual field testing (Humphreyfield analysis (HFA II 750) showed relativescotomas of the left eye, mainly in both lowerquadrants. Visual evoked potential (VEP)examination of the left eye showed prolongedlatency and decreased amplitudes, suggestiveof optic nerve dysfunction.

Orbital MRI (T1 weighted) scans showed aproptosis of the left eye and a large retrobulbar,intraconal mass that stained intensely withgadolineum contrast (Fig 1, bottom left). Com-puted tomography (CT) imaging also showedan intensely staining retrobulbar tumour with-out calcifications, that encased and slightlydisplaced the optic nerve. There was no “tram-tracking” sign or bone involvement. Notumour extension into the optic canal orintracranially was noted. Orbital colour Dop-pler ultrasound imaging showed a highly vas-cularised retrobulbar mass with a verticaldiameter of at least 25 mm (Fig 2, top left).

Since, on imaging, no evident diagnosiscould be made, we decided to perform abiopsy on the lesion through a lateral orbit-otomy. At surgery, the tumour was pale andsolid. Histopathological examination of theincisional biopsy specimen showed whorls ofmeningothelial cells, with small nuclei and

inconspicuous nucleoli, consistent with ameningioma (Fig 2, bottom).

After surgery we observed the patient for 9months. During this period her left (cor-rected) VA deteriorated to 0.2 and her leftvisual field showed progression of her scoto-mas. This prompted us to treat her with frac-tionated SRT in March 2001. The radiation,delivered with a 6 MV linear accelerator (Var-ian), was given 5 days a week at 1.8 Gy perfraction, with a cumulative dose of 54 Gy.Treatment planning was based on orbital MRImatched with CT scans. A non-invasive stere-otactic frame was fixed with an external coor-dinate system (one isocentre). Target and sur-

rounding tissues at risk were defined asvolume of interest on contrast media en-hanced T1 weighted MRIs and transferred toCT by the stereotactic localisation techniqueusing a three dimensional planning system (XPlan, Radionics). Portals were optimisedusing a beam’s eye view technique. Fiveirregularly shaped non-coplanar beams(arcs) per treatment were used. Beam shap-ing was done with a mini-multileaf collima-tor (Radionics). No early complications of theradiation treatment were noted. At 6 monthsafter SRT, the (corrected) VA of her left eyehad recovered to 0.8, while no RAPD wasobserved.

Figure 2 Top left. Ultrasound examination at presentation. A large, heavily vascularisedretrobulbar mass is visible. Top right. Six months after radiotherapy, the tumour hasdiminished in size and vascularisation. Note that a different depth setting of the ultrasoundsystem has been used. Bottom. Histopathology of the optic nerve tumour, showing whorls ofmeningothelial cells, with small nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli (haematoxylin and eosin,×200 original magnification).

Figure 1 Top left. Appearance of a 41 year old woman with a biopsy proved optic nervesheath meningioma before SRT. Note the left exophthalmos and periocular swelling. Top right.Post-treatment appearance. Note the decrease of the fullness of the left eyelids. Also note theright upper lid retraction secondary to left upper lid ptosis. Bottom left. Orbital MRI scan (T1weighted with fat suppression and gadolinium contrast enhancement) at presentation. Bottomright. Six months after radiotherapy. A decrease of both tumour size and proptosis is clearlyvisible.

246 PostScript

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

Her periocular swelling had markedly di-minished (Fig 1, top right). Compared to pre-vious measurements, the protrusion of theleft eye had diminished by 4 mm. Fundus-copy, however, showed mild pallor of the leftoptic nerve head. Visual field testing showedunchanged loss of the left visual field com-pared to pretreatment values, with a higherfoveal threshold. VEP measurements showedimproved amplitudes, but prolonged latencycompared to previous examination. Orthopticexamination showed ductions similar to thosebefore treatment. Post-treatment MRI re-vealed a markedly decreased tumour size anda decrease of exophthalmos (Fig 1, bottomright). Colour Doppler ultrasonographyshowed a decrease in tumour size with mark-edly diminished vascularisation (Fig 2, topright). At the last follow up visit, 16 monthsafter treatment, her left VA and visual fieldswere stable.

CommentAs in the recent report on a presumed ONSMby Moyer et al,5 fractionated SRT in our biopsyproved case gave a remarkable visual recoverywithout detectable side effects. Both the sizeand the blood flow of the tumour regressedwithin the first 6 months, leading to reducedexophthalmos and periocular swelling. Theeffect of restored cosmesis was important tothis young woman whose main complaintwas her unilateral exophthalmos.

Since our follow up is limited to 16months, no conclusions with regard to longterm outcome can be made. More cases ofSRT for ONSM need to be studied over alonger period of time to assess the efficacy ofthis treatment.

AcknowledgementsThis study was presented in part at the 196th Annual

Meeting of the Dutch Society of Ophthalmologists,

Groningen, the Netherlands, March 2002.

The SWOO foundation is kindly acknowledged for

financial support.

A D A Paridaens, R L J van RuyvenRotterdam Eye Hospital, Oculoplastic Service

W M H EijkenboomErasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, Department of

Radiotherapy

CM MooyErasmus University Rotterdam, Department of

Ophthalmopathology

WA van den BoschRotterdam Eye Hospital, Oculoplastic Service

Correspondence to: A D A Paridaens, MD PhD, TheRotterdam Eye Hospital, Oculoplastic Service,

Schiedamsevest 180, 3011 BH Rotterdam,Netherlands; [email protected]

Accepted for publication 25 July 2002

References1 Dutton JJ. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas.

Surv Ophthalmol 1992;37:167–83.2 Turbin RE, Thompson CR, Kennerdell JS, et

al. A long-term visual outcome comparison inpatients with optic nerve sheath meningiomamanaged with observation, surgery,radiotherapy, or surgery and radiotherapy.Ophthalmology 2002;109:890–900.

3 Eng TY, Albright NW, Kuwahara G, et al.Precision radiation therapy for optic nervesheath meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol BiolPhys 1992;22:1093–8.

4 Lee AG, Woo SY, Miller NR, et al.Improvement in visual function in an eye witha presumed optic nerve sheath meningiomaafter treatment with three-dimensionalconformal radiation therapy. JNeuro-ophthalmol 1996;16:247–51.

5 Moyer PD, Golnik KC, Breneman J. Treatmentof optic nerve sheath meningioma withthree-dimensional conformal radiation. Am JOphthalmol 2000;129:694–6.

Severe interferon associatedretinopathyInterferon alfa is used in various humanmalignancies for its antitumour activity. Oneof its ocular side effects is retinopathy.1 Inter-feron associated retinopathy is generally mildand resolves completely. We describe a severeretinopathy in a hypertensive patient treatedwith interferon for multiple myeloma.

Case reportA 56 year old man presented with a 3 weekhistory of deterioration and distortion of rightvision. Visual acuities (VA) were 6/60 rightand 1/60 left. Funduscopy revealed bilateralextensive peripapillary cotton wool spots,retinal thickening, optic disc hyperaemia, andblot haemorrhages. Arteriolar changes wereminimal.

He was anaemic (Hb 10.6 gdl/l) and slightlythrombocytopenic (platelets 93 × 109/l).Plasma viscosity was 1.59 (normal 1.5–1.7).Renal function was normal at presentation.

He underwent peripheral blood stem celltransplant for multiple myeloma 8 monthspreviously after having melphalan 110 mg/m2

and total body irradiation (including thehead) in a total dose of 1200 cGy given in sixfractions over 3 days. He then had interferonalfa therapy for 4 months, initially 3 megaunits three times a week, later reduced totwice a week. It was stopped immediatelyafter visual deterioration.

Five years previously, he had macular lasertreatment following left inferotemporalbranch retinal vein occlusion. On discharge 1year later, VAs were right 6/5, left 6/36.

He was a known hypertensive, takinglisinopril, but control was poor around the

time his VA began to deteriorate, withreadings up to 150/100 mm Hg. He was notdiabetic. His myeloma status was stable.Cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigen checked bypolymerase chain reaction (PCR) and pre-transplant HIV status were negative.

One week after presentation at the eyeclinic, VAs dropped to right 2/60, left fingercounting and did not improve after a course ofintravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day for3 days). He was registered blind.

A further 3 weeks later, bilateral cottonwool spots and haemorrhages were morenumerous and both foveas showed grossthickening with exudates (Fig 1). Fundusfluorescein angiography revealed retinalischaemia with capillary non-perfusion,pruning, and tortuosity of vessels, vessel wallstaining, and leakage (Fig 2).

Five months later preproliferative retino-pathy was noted and subsequent proliferativechanges were treated with bilateral panretinallaser photocoagulation. At 9 months, VAswere 1/60 right and left.

CommentIn a review article on interferon retinopathy,initial interferon alfa doses ranged from3–9 mega units three to six times perweek for several weeks.1 In a prospectiverandomised placebo controlled trial ofinterferon alfa therapy for maculardegeneration, retinopathy was noted withincreasing frequency in the highest dosegroup (5% of the patients taking 6 mega unitsthree times a week).2 The interferon doses inour patient were at the lower level of theseregimens.

Severity of retinopathy was found to berelated to the presence of the following riskfactors: large initial dosages, long duration oftreatment, and systemic diseases like diabetesmellitus or hypertension. Early onset of retin-opathy was also a good indicator of severity

Figure 1 Bilateral (right eye (A) and left eye (B)) extensive peripapillary cotton wool spots,retinal thickening with exudates, optic disc hyperaemia, and blot haemorrhages.

Figure 2 Fundus fluorescein angiography of the right eye: early frame (A) showing retinalischaemia with capillary non-perfusion, pruning, and tortuosity of vessels; late frame (B)showing vessel wall staining and leakage.

PostScript 247

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

and fundal examination up to 8 weeks fromstart of treatment was advocated for those atrisk.3

Significant visual impairment attributed tointerferon therapy was associated with macu-lar oedema in a hypoalbuminaemic butnon-hypertensive, non-diabetic patient4; andin two other cases in a case series report, oneof whom had poor control of blood pressureand the other an occasional mildly elevatedblood glucose level.5 All three patients hadresolution of the lesions by 2 months andsubsequently made good visual recoveries,unlike in our case.

In another case series report, two out ofseven patients on high dose interferon alfa-2bsuffered permanent visual loss after develop-ing macular oedema. Both patients werehypertensive and one had radiation treatmentto the brain. The latter later developed prolif-erative retinopathy as well.6

Deposition of immune complexes in theretinal vasculature has been postulated as apathogenetic mechanism for the retinopathy.5

Interferon alfa was also found to induceleucocyte capillary trapping in rat retinalmicrocirculation.7

Radiation may have contributed to thedevelopment of the clinical picture althoughits use in the treatment of myeloma isfrequent and ocular side effects have not beenwidely recognised in the past. Low doses tothe eye similar to that used in our patienthave been associated with retinopathyafter treatment of age related maculardegeneration.8

Retinal oedema is an indicator of severity ininterferon associated retinopathy. Early detec-tion of it, especially in hypertensives and dia-betics, may help avoid progression to perma-nent visual loss.

K L Tu, J Bowyer, K Schofield, S Harding

Correspondence to: Mr K L Tu, St Paul’s Eye Unit,Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool

L7 8XP, UK; [email protected]

Accepted for publication 29 July 2002

References1 Hayasaka S, Nagaki Y, Matsumoto M, et al.

Interferon associated retinopathy. Br JOphthalmol 1998;82:323–5.

2 Pharmacological Therapy for MacularDegeneration Study Group. Interferonalfa-2a is ineffective for patients withchoroidal neovascularization secondary toage-related macular degeneration. ArchOphthalmol 1997;115:865–72.

3 Soushi S, Kobayashi F, Obazawa H, et al.Evaluation of risk factors ofinterferon-associated retinopathy in patientswith type C chronic active hepatitis. NipponGanka Gakkai Zasshi 1996;100:69–76.(English extract)

4 Tokai R, Ikeda T, Miyaura T, et al.Interferon-associated retinopathy and cystoidmacular edema. Arch Ophthalmol2001;119:1077–9

5 Guyer DR, Tiedeman J, Yannuzzi LA, et al.Interferon associated retinopathy. ArchOphthalmol 1993;111:350–6.

6 Henjy C, Sternberg P Jr, Lawson DH, et al.Retinopathy associated with high-doseinterferon alfa-2b therapy. Am J Ophthalmol2001;131:782–7.

7 Nishiwaki H, Ogura Y, Miyamoto K, et al.Interferon alfa induces leukocyte capillarytrapping in rat retinal microcirculation. ArchOphthalmol 1996;114:726–30.

8 Mauget-Faysse M, Chiquet C, Milea D, etal. Long term results of radiotherapy forsubfoveal choroidal neovascularization in agerelated macular degeneration. Br JOphthalmol 1999;83:923–8.

Mass lesions of the posteriorsegment associated withBartonella henselaeBartonella (previously Rochalimea) henselae isthe infectious agent causing cat scratchdisease, a self limited regional lymphaden-opathy associated with flu-like symptoms.1 Inapproximately 10% of cases, extranodal dis-semination of the organism results in avariety of intraocular inflammatory lesions.1 2

We report a patient with acute Bartonellahenselae infection in whom the only physicalmanifestation was multiple, mass-like lesionsin the eye which resembled ocular metastases.

Case reportA 12 year old boy developed daily headachesand blurred vision. Four weeks later, he noted acentral grey spot in his left eye. Visual acuitywas 20/20 in his right eye and 20/400 left eye.Goldmann perimetry of the left eye revealed adense central scotoma with steep marginsnasally and moderate constriction of the tem-poral periphery. An afferent pupillary defectwas present on the left side. Slit lamp examina-tion was normal in both eyes. Funduscopy ofthe left eye showed nodular optic disc swellingwith peripapillary subretinal elevation (Fig 1).A large creamy-coloured mass (approximatelyone and one half disc diameter) withoutexudates or haemorrhages was present in themacula. Several smaller but similar, elevatedlesions of the choroid were detected in theperiphery as well as an inferior serous retinaldetachment. There was no evidence of ocularinflammation. An orbital ultrasound showedthe macular lesion to be a solid mass withoutassociated subretinal fluid (Fig 2).

Complete blood count, electrolytes, andglucose were normal. A sedimentation rate

was marginal at 18 mm/hour (normal lessthan 15 mm/hour). Antinuclear antibodieswere elevated at 1:320, speckled pattern.Rheumatoid factor was negative. Evaluationfor various infectious aetiologies was nega-tive, including Bartonella serologies (IgM andIgG). A systemic evaluation for a primarytumour causing possible ocular metastaseswas negative. The patient was empiricallytreated with doxycycline 100 mg twice dailyfor 10 days. The macular mass and choroidallesions resolved in 4 weeks. Shortly thereafter,the disc swelling resolved. Because a diagnosisremained lacking, serologies were repeated 1month later and revealed a marked rise ofBartonella titres, confirming a recent B henselaeinfection (B henselae IgM = 24, normal lessthan 16, and B henselae IgG = 1024, normalless than 256). Final visual acuity was 20/70left eye due to residual peripapillary andmacular gliosis.

CommentThe range of ocular findings associated with Bhenselae continues to expand. The classicfollicular conjunctivitis described with lym-phadenopathy and fever (Parinaud’s ocularglandular syndrome) is due to direct inocula-tion of the conjunctiva. Neuroretinitis, asyndrome of acute visual loss associated withoptic disc swelling and macular star, was thefirst established intraocular complicationfrom disseminated Bartonella.3 Since then,other reported intraocular findings includeinflammatory chorioretinal white spots, papil-litis, serous detachment, vitritis, uveitis, vas-culitis, retinal vaso-occlusive disease, and vit-reous haemorrhage.1–4 A mass lesion at theoptic nerve head has been noted in severalinstances.4 5 A solitary macular lesion withoutother ocular inflammatory findings has alsobeen reported.6 Such lesions in the posteriorpole have been presumed to represent a mas-sive focus of Bartonella inflammation.

We report a patient with a circumscribed,elevated lesion in the macula as well as othermass-like lesions at the optic nerve head and inthe choroid. These lesions occurred in theabsence of systemic or ocular inflammationand clinically resembled ocular metastases.This case highlights the importance of recog-nising the wide spectrum of ocular bartonello-sis. Furthermore, clinicians are reminded thatcat exposure is not essential for contracting thebacteria and, therefore, Bartonella titres shouldbe obtained whenever there is a clinical indexof suspicion, regardless of cat exposure.

A KawasakiDepartment of Neuro-ophthalmology, University Eye

Clinic of Lausanne, Hopital Ophtalmique, JulesGonin, Lausanne, Switzerland

D L WilsonDepartnment of Ophthalmology, Indiana UniversityMedical Center and Midwest Eye Institute, Indiana

University and Clarian Hospitals of Indiana,Indianapolis, IN, USA

Correspondence to: Aki Kawasaki, MD, HopitalOphtalmique Jules Gonin, Department of

Neuro-ophthalmology, Ave de France 15, CH1004 Lausanne, Switzerland;

Accepted for publication 9 August 2002

References1 Cunningham ET Jr, Koehler JE. Ocular

bartonellosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:340–9.

2 Ormerod LD, Skolnick KA, Menosky MM, etal. Retinal and choroidal manifestations ofcat-scratch disease. Ophthalmology1998;105:1024–31.

Figure 1 Fundus photograph of the leftoptic disc shows diffuse swelling andincreased surface vascularity. Additionally, amore focal elevation at the inferotemporalquadrant gives a nodule-like appearance tothe disc swelling (arrow). The irregular whitespot at the lower left corner of the figure is aphotographic artefact.

Figure 2 Orbital ultrasound at the maculaof the left eye demonstrates a focal area ofelevation and high reflectivity consistent witha solid mass lesion (arrows).

248 PostScript

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

3 Golnik KC, Marotto ME, Fanous MM .Ophthalmic manifestations of Rochalimaeaspecies. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118:145–51.

4 Solley WA, Martin DF, Newman NJ, et al.Cat scratch disease. Posterior segmentmanifestations. Ophthalmology1999;106:1546–53.

5 Cunningham ET Jr, McDonald HR, SchatzH, et al. Inflammatory mass of the optic nervehead associated with systemic Bartonellahenselae infection. Arch Ophthalmol1997;115:1596–7.

6 Pollock SC, Kristinsson J. Cat-scratch diseasemanifesting as unifocal helioid choroiditis.Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:1249–51.

Optic neuritis with markeddistension of the optic nervesheath due to local fluidcongestionDistension of the subarachnoid space of theoptic nerve is not a common feature of opticneuritis. We describe a patient with optic neu-ritis with swelling of the optic nerve head ofthe right eye. On magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) there was marked distension of theoptic nerve sheath due to an increase of fluidin the subarachnoid space. The location of thelesion in the optic nerve and concurrentinflammatory changes of the arachnoidtrabecula and septae may have had a role inthe pathophysiology of this condition.

Case reportA 38 year old man was admitted with pain oneye movements and loss of vision in the righteye. Best corrected visual acuities measured20/40 on the right and 20/20 on the left. Thepatient identified 16 out of 18 Ishihara plateswith the right eye and 18/18 with the left eye.There was a relative afferent pupillary deficit(RAPD) on the right. Funduscopy demon-strated a swollen optic disc on the right. Theleft optic disc was normal. Spontaneousvenous pulsations (SVP) were detectablebilaterally. Laboratory examinations, includ-ing red and white blood counts, C reactiveprotein, sedimentation rate, serologies forsyphilis, HIV, herpes, toxoplasmosis, Lymedisease and cytomegalovirus, as well as colla-gen vascular disorders and coagulopathieswere all in normal range. The right visual field(Octopus program G2) demonstrated awedge-shaped defect in the inferior nasal andtemporal visual field pointing towards themacula. The left visual field was normal.Neurological examination was normal. MRIof the brain was normal but showed enhance-ment of the right optic nerve in the T1weighted axial and coronal (not shown)image and hyperintense fluid in the expandedoptic nerve sheath on the T-2 weighted image(Fig 1A and B). Two days after admission thevisual acuity in the right eye decreased to20/100 and only two out of 18 Ishihara plateswere identified. SVP were no longer presenton the right. The swelling of the right opticdisc progressed and temporal peripapillaryPatton folds appeared, suggesting the diagno-sis of papilloedema (Fig 2). Within 2 weeksvisual acuity improved to 20/25 right eye andcolour vision returned to normal. A repeatMRI of the orbits 7 weeks later demonstratednormal diameters of both perioptic subarach-noid spaces (Fig 1C).

CommentDistension of the perioptic subarachnoidspace is a hallmark MRI feature of papil-loedema due to an intracranial mass lesion,inflammatory disease, and pseudotumourcerebri.1 Unilateral distension of the of the

optic nerve sheath due to increased fluid vol-ume of the subarachnoid space of the opticnerve has previously been reported in somepatients with optic hydrops, anterior ischaemicoptic neuropathy, and anatomical anomaliessuch as arachnoid cysts.2–4 This patient withoptic neuritis demonstrated marked distensionof the subarachnoid space of the right opticnerve, presumed to be caused by an increase oftotal fluid following optic neuritis. As allcerebrospinal fluid compartments are thoughtto communicate, equalisation of fluid via thechiasmal cistern would have been expected tooccur. The MRI scan of the brain and orbits,however, demonstrated localised and isolatedstasis of fluid in the right optic nerve subarach-noid space only. The reason for this fluidcongestion causing a optic nerve sheath com-partment syndrome could not be identified byneuroimaging. The site of inflammation of theoptic nerve and local anatomical variations andalterations of the subarachnoid space—forexample, the amount and number of trabecula

and septae in the subarachnoid space,5 mayhave a crucial role in the pathophysiology ofunilateral papilloedema.

H E Killer, A MironovDepartment of Ophthalmology and Radiology,

Kantonsspital Aarau, Switzerland

J FlammerUniversity Eye Clinic, Basel, Switzerland

Correspondence to: H E Killer, MD, Augenklinik,Kantonsspital Aarau, Aarau, Switzerland;

Accepted for publication 9 August 2002

References1 Brodsky M, Vaphiades M. Magnetic

resonance imaging in pseudotumor cerebri.Ophthalmology 1998;105:1686–93.

2 Jinkins JR. Optic hydrops: isolated nervesheath dilation demonstrated by CT. Am JNeuroradiol 1987;8:868–70.

3 Killer HE, Flammer J. Unilateral papilledemacaused by a fronto-temporo-parietal arachnoidcyst. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:589–91.

4 Spoor TC, Mc Henry JG, Lau-Sickon L.Progressive and static nonarteritic ischemicoptic neuropathy treated by optic nerve sheathfenestration. Ophthalmology 1993;100:306–11.

5 Killer HE, Laeng HR, Groscurth P. Lymphaticcapillaries in the meninges of the human opticnerve. J Neuro-Ophthalmol 1999;19:222–8.

MAILBOX

Corneal opacification followingkeratoplasty in the rat modelI read with great interest the excellentperspective by Plsková et al,1 in which theyraise the issue of transient corneal opacifica-tion following corneal transplantation in themouse model and argue that it might be dueto a sufficient number of endothelial cellsregaining function.

What the authors describe for the mousemodel also occurs in the rat model. In fact,

Figure 1 (A) Enhanced axial T1 weightedMRI with fat suppression demonstratingenhancement of the right optic nerve (arrow).(B) Axial T2 weighted MRI showshyperintensive fluid in the expandedsubarachnoid space due to increase of totalfluid (arrowhead). The hypointense opticnerve head protrudes into the posterior aspectof the globe (arrow). (C). Axial T2 weightedMRI 7 weeks later demonstrating normal opticnerves and subarachnoid spaces bilaterally.

Figure 2 Fundus photograph of the righteye demonstrating a prominent optic discwith blurred margins and nerve fibreobscuration in the superior and temporalquadrant. Patton folds are observed extendingto the macula. The veins appear engorged.

PostScript 249

www.bjophthalmol.com

on March 5, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://bjo.bm

j.com/

Br J O

phthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.87.2.249 on 1 F

ebruary 2003. Dow

nloaded from

most researchers on the rat model probablyhave this experience, but for some reason donot think it is very important and/or choose toignore it. Apart from the article by Williams etal,2 there is—as far as I know—only one otherauthor who has explicitly mentioned thistransient opacification. In their paper, Herbortet al3 wrote “The grafts began clearing 4 weeksafter surgery . . . and vessels in the graftdiminished from 6 weeks post-surgery.” and“It has to be noted that after acute rejectionmost corneas regain some clarity by 7–8weeks.” Transient corneal opacification alsooccurs in the rat model I used4 (AO rats (strainRT1u) served as recipients of corneas fromPVG rats (strain RT1c) and corneas weresutured with a single running suture). Alloge-neic transplanted corneas showed no initialopacification immediately postoperatively;neither did the syngeneic controls. All alloge-neic corneas “rejected” (or more preciselyshowed total opacification) around day 11–13and those corneas, when followed longenough, all cleared. Opacification remainedhigher than 2 (meaning an increased cornealhaze, but some anterior chamber structuresstill visible) at days 17–21 and became lowerthan 2 (slight haze) around days 21–32.

It would be exciting to know if the hypoth-esis put forward by Plsková et al1 would alsoapply to the rat model and to find out if this“clearing” of the opacification also occurs inother rat strains than the ones mentioned.

Plsková et al have raised a very importanttopic where a lot of uncertainty still exists,and which warrants further research.

Ilse ClaerhoutDepartment of Ophthalmology, Ghent University

Hospital, De Pintelaan 185, 9000 Gent, Belgium;[email protected]

References1 Plsková J, Kuffová L, Holán V, et al.

Evaluation of corneal graft rejection in amouse model. Br J Ophthalmol2002;86:108–13.

2 Williams KA, Coster DJ. Penetrating cornealtransplantation in the inbred rat; a newmodel. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci1985;26:23–30.

3 Herbort CP, Matsubara M, Nishi M, et al.Penetrating keratoplasty in the rat: a model forthe study of immunosuppressive treatment ofgraft rejection. Jpn J Ophthalmol1989;33:212–20.

4 Claerhout I, Beele H, Verstraete A, et al. Theeffect of duration and timing of systemiccyclosporine therapy on corneal allograftsurvival in the rat model. Graefes Arch ClinExp Ophthalmol 2001;239:152–7.

Surgery for glaucoma in the 21stcenturyThe authors of the article “Surgery forglaucoma in the 21st century”1 should becommended for attempting to tackle thisissue. Nevertheless, we do feel that their fun-damental points and principal argumentsmerit reconsideration.

The authors state categorically that “Thisfinding of a higher ‘failure’ rate based onintraocular pressure after ‘non-penetrating’surgery compared with trabeculectomy hasbeen a finding in the majority of randomisedtrials comparing the two procedures” andthen go on to quote three references allegedlysupporting this remark.

One of the three studies2 reports lowermean IOP with deep sclerectomy compared totrabeculectomy (although not statisticallysignificant) and almost identical successrates. What was significant was the dramati-cally lower complication rates with deep scle-rectomy.

When discussing the other two papers3 4 itis of paramount importance to understandthat given the long learning curve associatedwith deep sclerectomy, it is neither fair norscientifically sound to compare a surgeon’slast 20 cases of trabeculectomy with his first20 cases of deep sclerectomy. As an example,one group4 reported 0% success rate in theirfirst series of viscocanalostomy patients andthen presented their second series with asuccess rate of 15%.4 The same group alsoanalysed the depth of their dissection of thedeep sclera6 to find that they dissected toosuperficially in 48% of their cases and toodeeply in 17%; meaning that the proper depthof dissection, which should bisect transver-sally the Schlemm’s canal deroofing it, wasnot achieved in the majority of their cases.

The authors also failed to cite publishedlong term (43.2 (SD 14.3) months) results fordeep sclerectomy with collagen implant.7 Thestudy provided a qualified success rate of94.8% and the complete success rate, 61.9%after 60 months (survival analysis), with amean IOP at end of follow up of 11.8 (SD 3)mm Hg. Although the study reports anon-randomised consecutive series of patient,it should be taken as a proper indication ofresults achieved by experienced surgeons.

It should be taken into consideration thatnon-penetrating surgery is a broad genre ofsurgery, under which different surgeons per-form fundamentally different procedures thatinclude sinusotomy, ab externo trabeculec-tomy, deep sclerectomy with or without theuse of an implant, viscocanalostomy, perform-ance of postoperative goniopuncture, and theuse of antimetabolites. The different tech-niques have one thing in common, theelement of non-perforation.

What is true is that this type of surgery iscontinuously evolving, so it is unlikely that aproper judgment can be made yet. At the riskof sounding dramatic, it is valid to say thateditorials like the one by Khaw et al seem toindirectly sign a death certificate of non-penetrating surgery. It is much more useful toencourage research in non-penetrating sur-gery, including multicentre randomised stud-ies, to see if trabeculectomy will remain king.

T ShaarawyGlaucoma Unit, Memorial Research Institute of

Ophthalmology, Giza, Egypt;[email protected]

References1 Khaw PT, Wells AP, Lim KS. Surgery for

glaucoma in the 21st century. Br J Ophthalmol2002;86:710–1.

2 El Sayyad F, Helal M, El Kholify H, et al.Nonpenetrating deep sclerectomy versustrabeculectomy in bilateral primaryopen-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology2000;107:1671–4.

3 Chiselita D. Non-penetrating sclerectomyversus trabeculectomy in primary open angleglaucoma surgery. Eye 2001;15:197–201

4 Jonescu-Cuypers C, Jacobi P, Konen W, etal. Primary viscocanalostomy versustrabeculectomy in white patients withopen-angle glaucoma: a randomized clinicaltrial. Ophthalmology 2001;108:254–8.

5 Dietlein TS, Krieglstein GK. Morphology andpressure-reducing efficacy afterviscocanalostomy. Paris: Closed Meeting ofthe European Glaucoma Society, 2001:23.

6 Dietlein TS, Luke C, Jacobi PC, et al.Variability of dissection depth in deepsclerectomy: morphological analysis of thedeep scleral flap. Graefes Arch Clin ExpOphthalmol 2000;238:405–9.

7 Shaarawy T, Karlen M, Schnyder C, et al.Five-year results of deep sclerectomy withcollagen implant. J Cataract Refract Surg2001;27:1770–8.

NOTICES

Role of optometry in Vision 2000The latest issue of Community Eye Health (No43) discusses the mobilisation of optometry todeal with uncorrected refractive error, whichis now a major cause of functional blindness.For further information please contact: Jour-nal of Community Eye Health, InternationalCentre for Eye Health, Institute of Ophthal-mology, 11–43 Bath Street, London EC1V 9EL,UK (tel: +44 (0)20 7608 6910; fax: +44 (0)207250 3207; email: [email protected];web site: www.jceh.co.uk). Annual subscrip-tion (4 issues) UK£25/US$40. Free to workersin developing countries.

International Centre for EyeHealthThe International Centre for Eye Health haspublished a new edition of the Standard List ofMedicines, Equipment, Instruments and OpticalSupplies (2001) for eye care services indeveloping countries. It is compiled by theTask Force of the International Agency for thePrevention of Blindness. Further details: SueStevens, International Centre for Eye Health,11–43 Bath Street, London EC1V 9EL,UK (tel: +44 (0)20 7608 6910; email:[email protected]).

Second SightSecond Sight, a UK based charity whose aimsare to eliminate the backlog of cataract blindin India by the year 2020 and to establishstrong links between Indian and British oph-thalmologists, is regularly sending volunteersurgeons to India. Details can be found at thecharity web site (www.secondsight.org.uk) orby contacting Dr Lucy Mathen ([email protected]).