Post-operative care of a child following repair of a Truncus … · 2014-10-08 · Post-operative...

Transcript of Post-operative care of a child following repair of a Truncus … · 2014-10-08 · Post-operative...

Working with Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital and based in the School of Child and Adolescent Health, University of Cape Town

Post-operative care of a child following repair of a Truncus Arteriosus

Primary Author: Addila Abdulla Reviewed and updated by the Child Nurse Practice Development Initiative, January 2014

Practice guideline only. Please also consult your own hospital’s protocols/policies.

References 1. Lucile Packard Children's Hospital. 2014. Truncus Arteriosus. http://www.lpch.org/DiseaseHealthInfo/HealthLibrary/cardiac/truncus.html [Accessed

January 8, 2014] 2. Dixon, M. & Crawford, D. 2012 Paediatric Intensive Care Nursing. Wiley-Blackwell: West Sussex, UK 3. McElhinney, D.B. & Wernovsky, G. Truncus Arteriosus. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/892489-overview#a0199 [Accessed January 8, 2014] 4. Hazinski, M.F. 1999. Manual of Paediatric Critical Care. Philadelphia: Mosby 5. Picture: http://www.heartbabyhome.com/category/ta/ [Accessed January 8, 2014]

Surgical management and potential post-operative complications4

Trucus arteriosus is diagnosed primarily by physical assessment and echocardiogram1. Early identification of the condition is crucial so that complete surgical repair can be performed in the first weeks/months of life to prevent cardiac failure , pulmonary vessels damage and thromboembolitic events4. The repair is performed whilst on cardiopulmonary bypass – the VSD is patch closed and the truncus becomes the aorta. The pulmonary arteries are then connected to the right ventricles by use of a conduit4. Closure of the chest may not be immediately possible4. Post-operative complications include: ventricular arrhythmias, bleeding, poor ventricular function, tamponade, pulmonary hypertension and infection4.

Nursing Care The following care should be delivered in addition to routine essential nursing care.

Assessment of pain and provision of adequate analgesics and sedation, coupled with minimal handling: A sternotomy and chest drains are painful – patient should be kept pain free, particularly since agitation and pain can lead to pulmonary hypertensive crises.

Strict monitoring of fluid input and output: Fluid input will be restricted in immediate post-operative period. Need to be able to quickly identify an emerging inappropriate fluid balance or signs of renal failure. Aim for 1ml of urine/kg/hr. Diuretics to be given as prescribed.

Monitoring of vital signs (HR, BP & CVP) can also indicate whether additional fluid is required or decreased cardiac output is present. They should be initially recorded ¼ hourly, then ½ and one hourly; changing trends should be reported. Inotropes should be meticulously documented and titrated according to patient need.

Observation for bleeding: Drains loss, content and amount should be recorded. Losses of >3ml/kg/hr should be reported. Drains to be milked to maintain patency. Clotting profile should be checked regularly and blood products administered if indicated.

Prevention/management of arrhythmias: The ECG should be strictly observed and electrolytes carefully monitored and replaced if insufficient.

Maintenance of the arterial line: necessary to ensure continuous blood pressure monitoring and the ability to take frequent blood gases, full blood count, clotting profile and electrolytes.

Prevention of (wound) infection: Effective hand washing and adherence to infection control policies is vital. Wound to be constantly observed signs of infection (redness, heat, swelling, pus).

Pupil checks: Should be performed on admission and then daily to ensure early detection of any serious neurological event.

Definition: The term Truncus Arteriosus describes the congenital cardiac condition in which the great vessels

leaving the heart fail to completely separate during embryonic development into the pulmonary artery and the aorta.1

It is accompanied by a Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) and a single truncal valve2.

Epidemiology: Truncus Arteriosus occurs during the first 8 weeks of foetal development1. The exact cause of this abnormality is unknown but genetics and environmental factors are thought to contribute1. It can be also associated with other chromosomal disorders1. It is rare, occurring in 5-15 of 100,000 live births 3. It is classified into four types determined by the manner in which the pulmonary arteries arise from the single vessel2.

Pathophysiology

• In Truncus Arteriosus, the single great vessel is situated above the VSD and therefore receives blood from both ventricles. Pressure in the ventricles is equal4.

• Oxygenated blood from the left side will mix with deoxygenated blood from the right side causing cyanosis4.

• The degree of cyanosis is determined by the pulmonary blood flow. Decreased pulmonary blood flow from the heart will result in less blood being oxygenated. Therefore the blood returning into the left atrium is less oxygenated – in this situation cyanosis will be more severe4.

• Pulmonary blood flow may be determined by either the presence of pulmonary stenosis or pulmonary pressures. In the initial period post-birth, pulmonary pressures will be greater than systemic. Blood will preferentially flow to the systemic vessels meaning that whilst systemic BP will be sufficient, oxygenation will be poor. As pulmonary pressures reduce, more blood will flow to the pulmonary system causing a decrease in BP and an increase in saturations2.

• Newborn and pre-operative care is therefore focused on balancing the pulmonary pressures against the systemic pressures to ensure adequate BP and saturations2.

• Prolonged increased pulmonary blood flow can cause pulmonary hypertension and ‘wet lungs’ 2.

Signs and Symptoms

• Newborn infants will likely present with cyanosis in the first few days of life2. This may be accompanied by sweating, pale, cool skin, tachypnoea, tachycardia, poor feeding and poor weight gain.

• If left untreated, signs of congestive cardiac failure will then progressively develop4.

• Symptoms may also depend on the presence of other cardiac abnormalities. The presence and extent of pulmonary stenosis will determine the amount of pulmonary blood flow, the degree of hypoxaemia and the risk of pulmonary hypertension4.

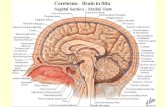

Diagram of Type One Truncus Arteriosus and a VSD.

![Co-operatives Act [No. 14 of 2005] - SAFLII · “services co-operative” means a co-operative that engages in housing, health care, child care, transportation, communication and](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5ed5668375bf2c1ab11572d5/co-operatives-act-no-14-of-2005-aoeservices-co-operativea-means-a-co-operative.jpg)