Portrait of Debussy 2, Debussy and Bartók

-

Upload

metronomme -

Category

Documents

-

view

18 -

download

7

description

Transcript of Portrait of Debussy 2, Debussy and Bartók

Portrait of Debussy. 2: Debussy and Bartók

Anthony Cross

The Musical Times, Vol. 108, No. 1488. (Feb., 1967), pp. 125-127+129-131.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0027-4666%28196702%29108%3A1488%3C125%3APOD2DA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Y

The Musical Times is currently published by Musical Times Publications Ltd..

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtainedprior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content inthe JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/journals/mtpl.html.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academicjournals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers,and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community takeadvantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

http://www.jstor.orgThu Aug 16 18:28:19 2007

The melody undoubtedly remained the same for the following stanzas, in which the author's assonant verses recount the entire career of the Duke of Normandy, his conquests, and the 1066 coronation.

The poet makes much of the contrast between living conditions in the time when William exercised his authority to ensure the preservation of individual rights and the period of instability after his death; nowadays, he complains-not without bitterness- there is no longer any security guaranteed by rights, for everyone fights for his own interests (stanza 8). Perhaps we can see in this passage an allusion to the troubles which broke out after William's death and which were faithfully recorded by Orderic Vitalis.

It was certainly during those troubled years which preceded the accession in 1106 of Henry I that these elegiac stanzas came to be written. They may well have been the work of a senior member of the Norman clergy, such as Guillaume Bonne-Ame, an old monk of le Bec, later Archbishop of Rouen, or Gilbert Maminot, Bishop of Lisieux, who was present at William's last moments, or perhaps a learned monk of Saint-~tienne de Caen. In any case, Orderic Vitalis must have read these lines and similar ones, of which quantities were written after William's death: 'Egregii versificatores de tali viro unde tam copiosum thema versificandi repererunt, multa concinna et praeclara poemata protulerunt'.

Most of these texts were doubtless intended simply for reading or declamation. The present planctus includes notation, and must have been sung at non- liturgical gatherings, if not at the court of the

Portrait of Debussy-2

Dukes of Normandy. Although its melodic lines make some departures from the forms of ecclesiasti- cal plainchant, it is in these that, for several reasons, it has its roots.

Clearly, as is the case in the majority of such laments, the mode used is the Dorian-at the time considered most expressive of sorrow-but the composer has palpably departed from the customary bounds of Gregorian composition. Whereas in true Gregorian music-sometimes known as Gregorian 'classic chant' ('vieux fonds')-the typical structure of the protus authente (the mode's basic form) would be based on the fifth D-A, and would be sur- mounted by the third A-C, here the compass is based on the same fifth, but extended upwards by a fourth, A-D. Finally, as a last comment, the return to the final is effected by the use of a lower note (C-D-D), as in certain pieces, especially sequences, of the early Middle Ages. These few observations serve to demonstrate that the melody may well date from the same period as the text.

Certainly this planctus, luckily preserved in a fragment of manuscript, is no masterpiece of versi- fication or of composition; neither does it constitute a document of great value for the historian. But the text brings us an echo of popular sentiments of the time, and the music contributes to our files on secular music at the end of the l lth century.

-translated by G. W. Hopkins

Sorne of the malerial in this article has already appeared in the 'Revue de Musicologie', Vol L, 2, 1964, p.225-8; it is reproduced by courtesy of the editor.

Anthony Cross /

DEBUSSY AND BARTOK In this ~er ies of articles (started last month by Jeremy Noble's on Debussy and Stravinsky) we attempt to build a composite portrait of Debussy the musician through examination of the very different impressions he left on the music ofother composers: in general, and also in particular by documentation of what works they heord, and when, their statements, and the re- flections found in their own compositions.

On several occasions Bart6k referred to his debt to Debussy. It is however unwise to accept a com- poser's thoughts on his own work at their face value, and the circumstances which call forth such state- ments must always be taken into account. Only in connection with a close study of the music itself can they be evaluated at their full worth.

In his contribution to the Ravel memorial issue of La revue musicale (1938), Bartok-for obvious reasons-lays great emphasis on the reorientation of Hungarian cultural life towards that of France after three centuries of German domination:

It was then that a change of direction was effected. Debussy appeared and henceforth the

musical hegemony of France replaced that of Germany. The young Hungarian musicians who were working at the beginning of this century, among whom I counted myself, were already orientated in other fields towards French culture. One can easily imagine the significance for then1 of Debussy's appearance on the musical scene; the revelation of this art permitting them at last to turn towards the musical culture of France.

Yet for Bartok there was never to be more than a momentary turning away from the essentially Ger- man tradition within which his early style had been formed, and which represents all that Debussy opposed in music. Rather we find in Bart6k's mature work a radical extension and reformulation of certain aspects of this tradition, as the composer himself confirmed in an interview accorded to Serge Moreux in 1939:'

Debussy's great service to music was to re-awaken among all musicians an awareness of harmony and its possibilities. In that he was just as important as Beethoven who revealed to us the

'Reprinted in S. Moreux, Bartdk, London 1953

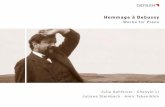

Piano Works

Images, Series 1 . . Images, Series 2 .. Children's Corner . . Prtludes, Book 1 . . PrCludes, Book 2 . . Etudes, Book 1 . . Etudes, Book 2 . .

Vocal Works

Ariettes OubliCes . . FCtes Galantes 1 . . FCtes Galantes I1 . . Proses Lyriques ..

Trois Pohmes de Sttphane MallarmC . . . .

Chamber Works

String Quartet . .

Sonata for Flute, Viola and

All the music of Debussy is available from

UNITED MUSIC PUBLISHERS LT

meaning of progressive form, and as Bach who showed us the transcendent significance of counterpoint . . . Now, what I am always asking myself is this: is it possible to make a synthesis of these three great masters, a living synthesis that will be valid for our own time?

This, however, is certainly an exaggeration of the significance of Debussy's harmonic innovations for Bartok's development. A truer picture is given by Bartok's Autobiographical Sketch (1921)2 upon which by its very nature we might place niost reliance:

In 1907, at the instigation of Kodaly, I becanie acquainted with Debussy's work, studied it through thoroughly and was greatly surprised to find in his work pentatonic phrases similar in character to those contained in our peasant music. I was sure these could be attributed to the influence of folk music from Eastern Europe, very likely from Russia. Similar influences can be traced in Stravinsky's work. It seems there- fore that in our age modern music has developed along similar lines in countries geographically remote from each other. It has becoille rejuve- nated through the influence of a kind of peasant music that has remained untouched by the musical development of the last centuries. Mywork. . . from Opus 4 onwards tried to conyey something of the development just described.

(It is incidentally clear from this passage that he first became acquainted with Debussy's music in 1907 and not in 1905, when he visited Paris to com- pete for the Prix Rubinstein, as some commen-tators have made out.)

Bartok clearly regarded his work (with that of Kodaly) as an essentially independent development. though retrospectively it could no doubt be seen to form part of a coherent tradition with the music of Debussy and Stravinsky. This is borne out by the chronology of events. Bartok's first folksong expe- dition was made in 1905, the first collection of arrangements, made in collaboration with Kodaly, was published in December 1906, and Bartok him- self refers to his Second Orchestral Suite op 4 (1905-7)--completed before he knew a note of Debussy's music-as constituting the first step in the creation of a new musical language, through the influence of genuine folk music. Seen in this light the significance of Debussy for Bartok's development tends to fade into the background.

After 1907, Bartbk apparently made a close study of Debussy's music. Kodaly had returned from Paris in the autumn of that year bringing back with him a few pieces by Debussy including the Trois chansons de France which he remembers particularly interested B a r t t ~ k . ~ In Budapest he is known to have purchased copies of several works by Debussy : the Quartet (in October 1907) and between 1907 and 1911 much of the piano music including Pour Ie piano, L'isle joyeuse, Images I and ZI, and Preludes I.4 He also included works by Debussy in his piano recitals. All the more surprising then that the music

lReprinted in Tempo, London 1949150. Also in Bdln BarroA-Ausgcwiihlte Briefe, Budapest 1963 81nformation conveyed to the present writer by Professor Denijs Dille, Bartok Archivnm, Budapest 'Evidence obtained from invoices and the surviving contents of Rartok's library now in the Bartok Archivum, Budapest

126

Bartok wrote during the years 1907-11 (when his style was still far from achieving coherence and unity) should reveal, with the exception of the first of the Deux Images op 10 (1910), no unequivocal sign of Debussy's influence. It is true that there are many points of contact between the musical lan- guages of both composers: pentatonicism, modality and occasional whole-tone passages. But these de- vices are used by Bartok in an entirely personal manner and are not at all infused with Debussy's style as one would expect if they had been primarily the outcome of a study of his music. This is cer- tainly true of the First Quartet (1909) which is often regarded as revealing signs of a Debussyan influ- ence. It would seem more logical however to explain such similarities as the result of an influence common to both composers. The first movement of this Quartet, like that of the First Violin Concerto ( 1907-8), shows Bartok in a situation akin in many ways to that of the young Schoenberg. Folksong provided a means of escape from what he con-sidered to be the irnpasse of atonality on the one hand, and the constrictions of an exhausted, Straussian (tonal) chromaticisn~ on the other.

Debussy's problem (though not posed so acutely for a composer in the French tradition) was similar. Although he never shared Bartok's ethnomusico-log~cal attitude, there is ample evidence that he was fascinated by music outside the immediate Euro- pean heritage: folk music (not merely Russian as Bnrtok supposed5), p l a in~han t ,~ ofthe music the Renaissance masters and the Javanese music which he heard at the Paris Exhibition of 1899. No doubt the most profound stimulus of these sources was in the creation of a new musical poetic, but from a purely technical point of view they reveal a concept of tonality very different from that which had pre- vailed in Europe since the 17th century. Instead of the precise hierarchy of functional relationships kkhich define 'classical' tonality we find a relative indirierence as to function to be seen most clearly in the music by both composers which is based ex-clusively on whole-tone or pentatonic scales. It is dangerous to speak of modality since this implies a closed system to which the music of Debussy and Bartok cannot be confined. Nevertheless, as is al- mays the case with modality, there is a strong ten- dency in their music for tonality to be empirically defined by a self-sufficient melody, often with the support of long-held pedal points. Melody is no longer 'the surface of harmony' since the latter is often determined by melodic structure as Bartbk describes: 'The strange turnings of melodies in our East European Peasant Music showed us new ways of harmonization. . . The frequent use of the inter- va! of the fourth in our old melodies suggested to us the use of chords of the fourth. . .What we heard in succession we tried to build up in a simultaneous chord'.' Essentially there is a new freedom in the relationship of the vertical and horizontal dimen-

,Sse. for instance. Lockspeiser: D e b u ~ ~ . v : Li/e and.WindVol t l i ~ 2 , p. 132 and p.259 footnote 2 OJulla d'Almendra: Les modes ~rdgoriens duns l'oeuvre de C!:~ude Debussy, Paris 1947 -Tire Influence ofpeasant .Mu~icon Mcdern Music. Reprinted in Tcrnpo 1949150 and in S. Moreux c p rit

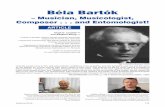

Bela Bartok

PIANO MUSIC Bartok Albums I & I1 each I 5 -Four plano pleces I g/-

Fourteen bagatelles, opus 6 I o I -

l'lano method (Ed. Reschofskc ) I 5 -Rhapsody, opus I ( T w o pianos) I 7 b

Scherzo ( T w o pianos) 25:-

Seten sketches, opus 9b 716

Ten eas) plano pleces 7 I6 The toung Rartok (orr . Dl l l e ) Book I1 I 7 '6

Ioung people at the plan0 Kooks 1 & 11 each 7 , 6

INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC Bagpiper, Oboe and piano 616

An e\ening in the tillage 51-Clarlnet (or 17101a) and plano

An etening in the \illage H a r p 4 6 ( irr. J ~ r d d n j ~ )

For children, Violin and piano I 2 '6 ( .h i . . L a t h u r c r ~ k ~ . )

For children, Cello and piano I 2 :b

( . lrr . Liebner)

For chiltlren, Guitar I 01-Three popular Hungarian songs 6 6

Flute and piano

Three popular Hungarian songs 6 6 Oboe and piano

POCKET SCORES 1)ances of Transyl\ania HPS 596 7 6

Ilungar~an plctures HPS 595 I 5 -Kosruth-sqrnphonlc poem HPS 79 2 I 5 -T\zo portraltu HPS 599 I 5 -

Complete cataJogues are avorlabJeJrom the

address below

Boosey & Hawkes 295 Regent Street London WI

sions and no longer a functional opposition as in traditional thought.

In December 1909 Bartok made another visit to Paris where he tried unsuccessfully to meet Debussys (nor did the two composers meet-apparently-when Debussy visited Budapest in December the following year). It is tempting to see more than mere coincidence in the fact that immediately after Bartok's return he should compose in the first linage op lO--even the title is significant-a hork in hhich he seems to have been momentarily captivated by Debussy's intangible poetic horld. In certain har- monic progressions (Ex 1) and especially in the employment of whole-tone scales (Ex 2) purely for purposes of colour (very different from their use in earlier works), we find the only instance in Bartok's ceuvre of a direct adoption of Debussyan harmony. A feature of the orchestral writing is the delicate, blurring superimposition of orchestral effects (tremolando. harmonics) and ornamentation (Ex 2), 'Recounted In S t e ~ e n s : Barroh. rev e d 1964. p.44 /T

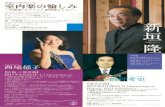

Hetfbn, 1910. december 5-611 este '/,a Brakor a Vigad6 nagytermeben

Debussy Claude FEART ROSE

hangversenyenekesn6 6s a

WALDBAUER-KERPELY vonbsnegves larsas6s k8zrernlik6dcsevei.

MOSOR : 1. Childrens Corner. 1 3. Vonosnegyes.

I. Doctor gradus ad ~arnarsuan I . Anln~e cl t r t ~decld4

$1.Jlmbo'6 Lullaby Ii A s l r r v t i r! blcn ryfhn~e. l iovrcmen~r x p r e i r . i111.Serenade lor the doll. 111. ~ n d a n t l ~ ~

IV. The Snow i s dancing IW. Ti13 nloderr

V. The 1110e ihephcrd. Elladia r Waldbauer -K~vpe ly ~ e n e ~ n , , ~ : ~ ~ ? I . Ooll~uogp', rake-urlk. , Irrraib? l i d a 9, lapoml i n a l ~ r ~ i € l

2. Fetes galantes. (Verlaine P. koltemenyei.) D, DP. roii

Szvrra zongorak~rercten,ei~:t, ilEn sourdlnc i,lokll F4zn Rose. b, Fantochei. i~clalr dc lune 5. a) Pagodes. d, oreen 1 b) Romrnage b Rameau.

Srevrd zungoiak~icrekerneilcf! anchi, peart I c) Jardins sous la pluie.

A Ooicnddrhr.rongerl CHA$iL Pr f i b r i , r r k . . . ~ ~ d c l l is?i:liid 2ongor#lrrrne'bdt ~ a i d .

Programme of a concert given by Debussy in Budapest. The young Waldbauer-Kerpely Qunrtet were close friends of Barfdk's; they had given the premisre o f his First Quartet in March 1910

a method which Debussy was to develop increasingly through the years, culminating in the extremely re- fined scoring of Jeux, but which is already present in PellPas and La mer. Whether Bartok was at this time consciously inspired by Debussy's orchestral works (he had had a score of La mer in his possession since February 1908): or whether he was simply attempting to transpose into orchestral terms De- bussy's impressionistic piano writing, is hard to tell. The originality of such orchestration lies in its exploitation of timbre: what Boulez has aptly termed orchestration-invention; more than ever be- fore invention and its orchestral realization are re- duced to a single act of creation.

Although in later works Bartok returns in the main to more traditional methods, examples of this impressionistic orchestration are not wanting: Bluebeard (some of the descriptive music following the opening of the seven doors), Four Orchestral Pieces op 12 (Prelude), Music for Strings, Per-cussion and Celesta (third movement), Concerto for Orchestra (Elegy), and the Third Piano Concerto (second movement). A more continuous applica- tion of this technique, however, occurs in The Miraculous Mandarin which shows signs of a close study of Debussy's orchestration. Bartok's orches- tral impressionism in these works often goes even beyond that of Debussy in its subjection of the

The Life and Music of Bela Bartok by H A L S E Y S T E V E N S

2nd ed 561-

'It should be in every self-respecting general library and in the hands of anyone who wants an understanding guide to the immense riches of Bartbk's works.' N O T E S

O X F O R D U N I V E R S I T Y P R E S S

primary elements of music to the demands of in- strumental colour. It is however important to realize that although Bart6k is using Debussyan principles, the harmonic flavour and timbres actually employed (celesta, harp and piano being frequently prominent) result in the creation of a poetic world entirely personal to Bartok.

It is particularly strange that during the years 1907-11, when Bartok was making himself acquain- ted with Debussy's piano music, the sets of piano pieces he composed (Op 6, Op 8, Op 9, the Four Dirges, 1910 and the Allegro barbaro, 191 1) reveal almost no trace of the French composer's highly original piano writing. These pieces tend to be either unenterprising pianistically or to foreshadow closely the bare, percussive writing of the later

Bartok. One might possibly detect a French in- fluence in the second of the Two Elegies (1909) but if so it is that of Ravel rather than Debussy. Bartok had apparent!^ bought a copy of Gaspard shortly before composing this piece. Occasional features of the later piano works, such as the bravura writing of the Studies op 18, are also slightly reminiscent of Ravel. In his maturity Bartok created, in pieces like the Night Music from the collection Out of Doors and Melody in the Mist (Mikrokosmos), anequivalent to Debussy's impressionism, but this is untypical of Bartok's piano music as a whole. With Debussy rhythm is frequently reduced to a continual vibra- tion (Mouvement) or to a uniform pulse as in the opening bars of La carh6drale engloutie, to permit, as it were, the realization of timbre effects9 (a favourite performance direction of Debussy is doucemenf timbre). The opposite however is true of Bartok, the timbre-quality of a particular chord being placed at the service of rhythm. It is fruitful in this respect to compare Bartok's Study in Alter- nating Thirds (Mikrokosmos V) with that of De- bussy (Preludes 11) (Ex 3) .

* 'Debussy hat mir viele Einsichte gegeben', Bartok

once remarked. Such insights especially in matters of harmonic and tonal organization no doubt en- abled Bart6k to clarify his ideas at a time when his own language had already begun to evolve in a similar direction. It is doubtful whether, unlike the influence of folksong however, these insights were decisive and there is no reason to suppose, danger- ous though such speculation is, that his later devel- opment would have been essentially different had Debussy never lived. On the other hand, Bartok's individual impressionistic vein was almost certainly initially inspired by Debussy's example, and the very fact that his first adoption of this technique coincides with his only excursion into Debussy's harmonic territory supports this view. Nevertheless, any attempt to define precisely the extent of De- bussy's influence is clearly fraught with difficulties since Bartok-like Debussy-showed an astonishing ability to make entirely his own whatever he

*For a detailed appraisal of this aspect of Debussy's language see Quelques a s p c t s de l3unii.ers sonor de Debussy b y S . Jaro-cinski in Debussy et I'Pvolution de la nlusique au XXienle sibcle, CNRS Paris 1965

borrowed from external sources, through the medium of an extremely personal style. Style in this sense is not merely a collection of technical pro- cedures but rather a unique manner of formulation, a way of thinking in musical terms which impinges on the musical language as a totality.

It is in this light that we can begin to glimpse the profound differences which underlie all the numer- ous correspondences we find in their work. Bartok intensifies certain traditional procedures (though he avoids those Paradis artiJciels of neo-classicism). The emphasis on motivic working (which becomes more and more thorough even to the extent of sug- gesting the all-pervading nature of serial technique) and the use of pre-established formal structures (arch forms) may be seen as an attempt to guarantee communication in the traditional sense and as com- pensation for the almost complete disappearance of a generalized system of tonal relationships existing prior to the act of composition. The internal re- lationships of pitch, rhythm and timbre remain fundamentally those of the past.

Debussy, though still apparently preserving a traditional syntax, transforms its significance by modifying these internal relationships; the emphasis on sonority and timbre and the consequent weak- ness of harmonic function leads to an abandonment of traditional phraseology and 'administrative' forms which are replaced by a process of continual renewal, mitigated only by the often remarked de- vice of immediate repetition of short phrases. 'La forme se compose par petites touches successives, reliees par un lien mysterieux . . .' What Debussy wrote of Mussorgsky is even truer of his own art. It is of course no accident that until recently academic analysis should have concentrated on composers like Bartok and Hindemith for whom traditional methods of analysis are still tenable; Debussy, on the other hand, has been virtually ignored, since analytical concepts derived from 19th-century music are impotent to reveal the true nature of his inno- vations. Unlike Bartok, Debussy, though inaugurat- ing a new tradition, stands outside previous tradition. In his own words: 'J'ai travaille a eliminer tout ce que I'on m'a appris'.

Bluebeard's Castle (complete opera) oc tavo score

The Wonderful Mandarin

Piano Concerto No I (miniature score)

Piano Concerto No 2 (miniature score)

String Quartets Nos 2 and 3 (miniature score) each

String Quartet No 5 (miniature score)

Catalogues and further deta~ls from

UNIVERSAL

2 , 3 F A R E H A M S T R E E T (DEAN S T R E E T )

LONDON PI 1

Mme Ditta BartOk-Pasztory and Szigeti are among the pro- fessors at the Bartok Seminar, July 20-August 4; details. Budapest Bureau of International Music Competitions, Buda- pest VI, Liszt Ferenc ter 8, Hungary. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra comes of age on Sept 15. An anonymous birthday gift of£500 will be used to commission a piano concerto from Richard Arnell. Priaulx Rainier's new work for the Cheltenham Festival, commissioned by the BBC, is Aequora Lunae (Srar of rAe .Moon), for orchestra, percussion, and wind solos. Elisaheth Lutyens's new work, commissioned by the BBC to open their first Chamber Music Concert in the Elizabeth Hall, is called and suddenly ir's evening for tenor (Robert Tear) and members of the BBC Symphony.

WHY FLORESTAN AND EUSEBIUS ? by Eric Sams

And twenty more such names and men as these Which never were. nor no man ever saw.

(Shakespeare) What's in a name? ( ib id)

For Schumann, everything was in a name, and his own was legion. Most famous of all are Florestan and Eusebius, the active and the passive aspects of his own personality.

No very compelling reason for this notion, let alone those names, has ever been suggested. A useful device for the writing of music criticism, perhaps? A confession of schizophrenia? Well,

Schumann's was certainly a dual nature (which may have influenced his choice of twos as pseudonyms1); but on the plainest evidence his duality was cycloid rather than schizoid .Vn any event it is not just Schumann but human nature to have both introvert and extrovert character traits. That is why the device of related but contrasting characters is found in fiction-which is where Schumann found it. 'In all his works Jean-Paul3 projects his own personality,

'ERLER, H. Roberf Schumann's Leben (1887) vol ii 233 et seq %LATER, F . & A. MEYER. Confinia psycitiatrica (1959) vol2 no 2

the novelist J. P. F. Richter (1763-1825)