Political Order and One-Party Rulepscourses.ucsd.edu/ps200b/Magaloni Kricheli Political Order and...

Transcript of Political Order and One-Party Rulepscourses.ucsd.edu/ps200b/Magaloni Kricheli Political Order and...

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

Political Order andOne-Party RuleBeatriz Magaloni and Ruth KricheliDepartment of Political Science, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305;email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2010. 13:123–43

First published online as a Review in Advance onJanuary 26, 2010

The Annual Review of Political Science is online atpolisci.annualreviews.org

This article’s doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220529

Copyright c© 2010 by Annual Reviews.All rights reserved

1094-2939/10/0615-0123$20.00

Key Words

autocracy, stability, single-party, dominant-party, elections

AbstractThe second half of the twentieth century and the beginning of thetwenty-first century have witnessed an unprecedented expansion of one-party autocracies. One-party regimes have become the most commontype of authoritarian rule and have proved to be more stable and togrow faster than other types of authoritarianism. We review the liter-ature on one-party rule and, using data from 1950–2006, suggest fouravenues for future research: focusing on autocrats’ ability to simultane-ously minimize threats from the elites and from the masses; focusingon the conditions that foster the establishment and the collapse of one-party regimes and on transitions from one type of authoritarianism toanother; focusing on the relationship between authoritarian electionsand democratization; and focusing on the global and international forcesthat influence the spread of one-party rule.

123

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

INTRODUCTION

As the twentieth century ended, optimismspread among supporters of democracy. Dur-ing the “third wave” of democratization(Huntington 1991), the world witnessed thecollapse of 85 authoritarian regimes, and thenumber of countries governed by elected offi-cials became greater than at any previous timein human history (Geddes 1999). The prospectsfor democracy had never seemed better. Yet thisspread of democracy was also accompanied bythe spread of one-party autocracies, and whenthe third wave of democratization came to a haltin the end of the twentieth century, one-partyregimes continued expanding.

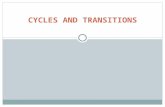

Figure 1 shows the distribution of sixpolitical orders—democratic, anarchic, mili-tary, monarchic, single-party, and dominant-party—during 1950–2006.1 Both single-partyand dominant-party regimes constitute whatwe refer to as one-party regimes; the dif-ference is that single-party regimes pro-scribe opposition parties’ participation in elec-tions (e.g., China or Vietnam today), whereasdominant-party regimes permit the opposi-tion to compete in multiparty elections thatusually do not allow alternation of politicalpower (e.g., Malaysia, Zimbabwe, Senegal af-ter 1976, Tanzania, Kenya and Gabon after theearly 1990s, Mexico before 2000, or Venezuelatoday).2 Dominant-party regimes are also

1The classification of democratic regimes is based onPrzeworski et al. (2000) and updates by Golder (2005) andBolotnyy & Magaloni (2009). The remaining observationsare divided into autocracies and anarchical regimes (Bolotnyy& Magaloni 2009). Anarchical regimes are those wherein oneof the following two types of governments exist: a govern-ment that was put into place by the military or by a civil-ian body to act as an intermediary between one regime andthe next; or a government that was popularly elected but iscurrently undergoing civil war or prevalent civil unrest andhence cannot function adequately. Drawing from the liter-ature on types of authoritarianism (Geddes 2003, Gandhi& Przeworski 2006, Gandhi 2008, Hadenius & Teorell2007, Magaloni 2008), autocratic regimes are subdividedinto monarchies, military regimes, single-party regimes, anddominant-party regimes (Bolotnyy & Magaloni 2009).2This distinction was originally highlighted by Sartori(1976), although he used the term hegemonic to refer to au-tocracies that permit opposition parties (see also Magaloni

known in the literature as “electoral authori-tarian” (Linz 2000, Diamond 2002, Schedler2002) or as “competitive authoritarian” regimes(Levitsky & Way 2002). Despite the im-portant differences between single-party anddominant-party regimes, we often refer to themtogether—as one-party regimes—and high-light this distinction only when it is relevantto our argument.

The figure suggests that even after the thirdwave, the world’s political order is predom-inantly autocratic, and that while the spreadof democracy came to a close in the mid-1990s, one-party regimes continued spreadingthroughout the first decade of the twenty-firstcentury. One-party regimes have now becomethe most common type of authoritarian rule,constituting 57% of the authoritarian regimesduring 1950–2006 and 33% of the total numberof regimes in the world.

The spread of one-party dictatorships hassparked a great deal of academic curiosity,and scholars have shown that compared toother types of dictatorships, one-party regimeslast longer (Huntington 1968, Geddes 2003,Magaloni 2008), suffer fewer coups (Cox 2008,Geddes 2008, Kricheli 2008), have bettercounterinsurgency capacities (Keefer 2008),and enjoy higher economic growth (Keefer2007, Gandhi 2008, Gehlbach & Keefer 2008,Wright 2008c). Why are one-party dictator-ships more stable than are others? Why dothey grow more and experience fewer violentthreats?

Puzzled by these questions, students ofauthoritarian regimes have been increasinglystudying the functions served by ruling partiesin one-party autocracies. They now view theruling party as having two interwoven func-tions that account for one-party rule’s supe-riority: a bargaining function, whereby dicta-tors use the party to bargain with the elites and

2006). Notice that we do not elaborate here on the distinc-tion between dominant-party democracies or “uncommondemocracies” (Pempel 1990), wherein one party rules fordecades under democratic conditions, and dominant-partyautocracies.

124 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

Anarchy Monarchy

Military

Single-party

Dominant-party

Democracy

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005

Perc

ent o

f cou

ntri

es

Year

Figure 1Political order: democratic, anarchic, military, monarchic, single-party, and dominant-party regimes during 1950–2006.

minimize potential threats to their stability; anda mobilizing function, whereby dictators use theparty machine to mobilize mass support.

We review this literature and propose waysof synthesizing its main findings. We then sug-gest two challenges to the current literature:the functionalist challenge and the endogeneitychallenge. According to the functionalist chal-lenge, arguments elucidating the role played bythe ruling party do not fully explain why au-tocrats frequently use parties instead of usingother institutional structures that could servesimilar functions. The endogeneity challengepoints out that autocrats might be encour-aged to use ruling parties under certain con-ditions, and these conditions might also affectthe regime’s survival prospects; if so, a merecorrelation between one-party rule and betterpolitical and economic performance resultingfrom these underlying conditions is being mis-taken for a ruling-party effect. To overcomethese theoretical and methodological chal-lenges, a deeper understanding of the underly-ing circumstances that foster the emergence of

one-party autocracies is required. We brieflyexamine the full scope of political transitionsduring 1950–2006. Using Markov estimates, weshow, first, that one-party dictatorships are fre-quently established on the ruins of another typeof dictatorship; second, that transitions fromone type of dictatorship to another are the mostcommon type of regime transition, amountingto 43% of the total number of regime transi-tions during 1950–2006; and third, that con-trary to the common view, compared to mili-tary rule and to anarchy, one-party regimes arethe least likely to transform to democracy af-ter their collapse. These three findings suggestthat transitions from one type of dictatorship toanother deserve more scholarly attention.

We conclude by suggesting four avenues forfuture research: first, focusing on the emer-gence and the collapse of one-party regimesand on transitions from one type of dictatorshipinto another; second, focusing on the chang-ing global and geopolitical trends of regimetransitions—to and from one-party regimes—before, during, and after the Cold War;

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 125

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

third, focusing on the relationship betweenauthoritarian elections and the prospects ofdemocracy; and fourth, focusing on the strate-gies dictators follow to appease simultaneousthreats to their stability from within the elitesand from within the masses.

THE FUNCTIONS OF THE PARTY

Co-Opting the Opposition andElite Bargaining

Autocrats are fundamentally interested in theirown survival in power (Tullock 1987, Wintrobe1998, Haber 2006). If autocrats rely too muchon terror, repression, and intimidation to sus-tain their rule, they become more vulnera-ble to agency and moral-hazard problems onthe part of their own security apparatus, uponwhich their ability to survive ultimately depends(Wintrobe 1998). In order to rule the coun-try, autocrats have to bestow resources on elitemembers, who, in turn, can use these same re-sources to overthrow the regime (Haber 2006).How can the autocrat appease the elites and dis-courage military threats to his stability?

Students of dictatorships have suggestedseveral hypotheses about autocrats’ use of po-litical parties and other pseudodemocratic in-stitutions to appease potential elite challengersand enhance their longevity. One hypothesis isthat dictators can use these institutions to dis-tribute economic transfers and rents, therebyco-opting potential rivals. Licenses, offices, andaccess to economic resources can be used in or-der to invest a large body of political playerswith a stake in the ruler’s survival (Wintrobe1998, Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003).

Autocrats’ ability to use this distributivestrategy can be limited, as suggested by Haber(2006), Magaloni (2008), and Debs (2007), byproblems of commitment on the part of the dic-tator’s opposition. The dictator is caught in adilemma when trying to buy off potential ri-vals using economic transfers, because it is notclear what prevents his rivals from taking thesetransfers and then using them to organize a con-spiracy against him. By trying to appease his

opponents he might unintentionally make themmore powerful, thereby increasing the threat tohis survival.

Another hypothesis is that dictators canbroaden their appeal by making policy con-cessions in a direction favored by potentialopponents. Using pseudodemocratic insti-tutions, including parties and legislatures,the autocrat can give voice to groups withinsociety, bargain with opponents, and makepolicy concessions to address their demands(Gandhi & Przeworski 2006, p. 17). By allow-ing non-regime-sponsored parties to accessthe legislature, dictators can provide somemeans for advancement into political officeand for limited policy influence. In selectivelyco-opting the opposition and manipulatingelectoral laws, dictators also create dividedoppositions and increase coordination costsamong their opponents (Diaz-Cayeros et al.2001; Lust-Okar 2005; Magaloni 2006, 2009).

Autocrats’ ability to use policy concessionscan be limited by problems of commitmenton the part of the dictator (Magaloni 2008).The mere existence of parties and legislaturedoes not necessarily mean that office-holdersin these institutions have power and influenceover policy outcomes, since after the threat ofrebellion or the need for cooperation has beenanswered, the autocrat can dismiss dissentingvoices arbitrarily and renege on his promises.To extract real policy concessions, non-regime-sponsored parties must be able to retain somemeans to threaten the dictator’s survival whenhe reneges on his promises by, for example,mobilizing voters in great numbers to thestreets.

Moreover, the literature lacks a consensuson the extent to which legislatures in fact serveas a constraint on dictators. Gandhi (2008) con-vincingly demonstrates that dictatorships withlegislatures grow more than do those withoutthem, and argues that legislatures constrain er-ratic and predatory behavior on the part ofrulers. Wright (2008a) suggests further thatlegislatures are only binding in single-partyand military regimes because these emerge innatural-resource-poor countries wherein “the

126 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

dictator concedes a legislature to ensure capitalowners that he will not confiscate their mobileassets” (Wright 2008a, p. 327). However, schol-ars have also argued that, in many one-partyregimes, the forum wherein policy concessionsactually take place is often not the legislature,and that the correlation between the existenceof legislatures and economic growth can be ex-plained by the higher levels of institutionaliza-tion enjoyed by autocrats who choose to havea legislature, not by the legislatures’ existence(Lust-Okar 2005, 2006; Magaloni et al. 2007;Masoud 2008; Shehata 2008; Blaydes 2009).Arriola (2009) shows, for example, that Africanleaders more often seek to co-opt the opposi-tion by offering access to the cabinet, whichprovides them with more direct control overstate resources. Blaydes (2009) similarly sug-gests that the Egyptian legislature has playeda limited role in policy making, and that officeseekers value legislative seats not because theyenable them to participate in policy making butbecause they grant legal immunity.

How can dictators establish a credible com-mitment to share power with potential oppo-nents when they face threats to their survival?Lazarev (2005), Brownlee (2007), Gehlbach &Keefer (2008), and Magaloni (2008) suggest athird hypothesis: More than using legislatures,dictators can use institutions within the rulingparty in order to make credible intertemporalpower-sharing deals with potential elite oppo-nents. Instead of policy, which can be changedarbitrarily by the dictator, the party controlssuccession and access-to-power positions. Partycadres will support the regime rather than seekto conspire against it only if, in exchange, theycan expect to be promoted into rent-paying po-sitions. When they do not expect such cred-ible power sharing, elite splits and instabilitybecome more likely (Magaloni 2006, Baturo2007). Hence, instead of counteracting threatsby groups within society, in this approach theparty serves to neutralize threats from withinthe ruling elite by guaranteeing them a share ofpower over the long run.

An implication of this account is that if for-mal and informal rules for accession to power

within the party are constantly violated, thecommitment breaks down, and the dictatorbecomes vulnerable. Thus, in this view, gov-ernance under one-party rule is portrayed as asystem of power sharing between the dictatorand the central leadership of his party, whichcontrols appointments and promotions that areexecuted according to certain informal and for-mal party norms. The dictator has ample pow-ers to appoint this leadership, but it has to comefrom within the party.

Boix & Svolik (2008) go one step further,arguing that power sharing under authoritari-anism “is sustained by the ability of each sideto punish the other party if it decides to deviatefrom that joint-governance arrangement and,in particular, by the credible threat of a rebellionby the ruler’s allies” (p. 2) (see also Gehlbach &Keefer 2008). In this account, the role of legisla-tures and parties is to facilitate collective actionamong the dictator’s allies to oppose potentialdictatorial abuses. This persuasive notion thatdictatorial institutions are backed by the credi-ble threat of a collective rebellion against dicta-torial abuses deserves further analysis. Dictatorsoften selectively abuse members of the rulingelite—they purge, imprison, or send their en-emies into exile—and get away with it becausethey are serving the interests of elite membersagainst each other (Tullock 1987). Collectiverebellions are also associated with coordinationand collective-action problems. Thus, under-standing the types of abuses that are likely toinspire collective rage is a promising directionfor future research.

The hypothesis that dictators use their rul-ing parties to facilitate bargaining with the elitesalso leads to a hypothesis about the likelihoodof such bargaining: The need to appease theelites stems from the autocrat’s fear of threatsto his stability on the part of the elites or of themilitary. Thus, we should expect the party tofunction as a power-sharing arrangement whenthe elites’ threats to the dictator’s rule are in-deed credible. The dictator has an incentive tobroaden his supporting coalition only when theopposition is powerful enough to threaten thestability of the regime (Bueno de Mesquita et al.

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 127

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

2003, Smith 2005, Gandhi & Przeworski 2006,Boix & Svolik 2008, Gandhi 2008).

This hypothesis relies, however, on the as-sumption that the autocrat knows when thethreats to his stability are severe enough to re-quire bargaining with the elites. Yet history hasshown that even the closest allies of the autocratmight eventually threaten his rule. Moreover,even when they are fully loyal to the regime,elites sometimes have an incentive to misrep-resent the degree of power and control the au-tocrat actually holds (Tullock 1987, Schatzberg1988, Wintrobe 1998). Dictators therefore of-ten face severe information problems with re-gard to the military’s and the opposition’s abil-ity to overthrow them. As a result, dictatorsmight find it beneficial to allow political compe-tition in order to gather information about theloyalty of their party cadres and about the ac-tual power their opponents enjoy (Ames 1970,Magaloni 2006, Birney 2007, Brownlee 2007,Cox 2008, Kricheli 2008, Blaydes 2009,Lorentzen 2009). Yet in order to produce cred-ible information, citizens’ participation shouldsomehow be tied to the actual power auto-crats enjoy. Can the dictator’s party, on topof co-opting the elites, create a vested interestamong the citizens? The following subsectionaddresses the literature on this question.

Building Mass Support

Autocrats are interested in their own survival,but this motivation does not necessarily meanthat they will opt to completely exclude themasses from the political process or to refrainfrom distributing rents and providing publicgoods. Instead, the same motivation that leadsthem to bargain with the elites often inducesautocrats to use the party machine as a patron-age system, whereby citizens receive rents fromthe government.

Mass support is important for the stabil-ity of the regime because it enhances cooper-ation within the ruling coalition. If the popu-lation overwhelmingly supports the party andthe party controls the distribution of power,positions, and rents, potential elite rivals have

no chance to gain power and spoils by com-peting outside the party (Magaloni 2006). Inmany one-party regimes, the party controlsland titles, fertilizers, subsidized housing, schol-arships, food, construction materials, and manyother privileges, which are distributed to themost loyal members of the party. One-partyregimes therefore virtually create a market forprivileges that are allocated based on degreesof loyalty (Wintrobe 1998; Lust-Okar 2005,2006). When they are well institutionalized,ruling parties should thus be understood as gi-ant patronage systems that give the citizens avested interest in the perpetuation of the regime(Magaloni 2006; Geddes 2006, 2008; Pepinsky2007).

The ability of a single party to monopolizemass support by controlling the state’s resourcesand using patronage networks has been called a“tragic brilliance” (Diaz-Cayeros et al. 2001)—tragic in that the party can remain in powereven without sustained economic prosperity,and brilliant in that voters play an active role insustaining the system. This system is held to-gether by a “punishment regime” wherein theparty distributes rents to citizens who remainloyal and withdraws them from those who de-fect. This punishment regime is particularly ef-fective at trapping poor voters into supportingthe dictatorship, because their livelihood de-pends on state transfers (Zhong & Chen 2002,Blaydes 2006, Magaloni 2006, Tezcur 2008).Citizens with alternative sources of income canbetter afford to make “ideological investments”in democratization and oppose the regime.

This tragic brilliance is also captured byHavel (1978), who lamented that under com-munism every acquiescent citizen had becomea perpetrator as well as a victim. Thanksto the command economy, the CommunistParty could control access to virtually everyvaluable resource, job, or privilege and couldthus threaten to withdraw access to any ofthese if citizens refused to acquiesce. To sus-tain this punishment regime, a strong partyorganization is required to acquire informa-tion about citizens’ loyalties and to implementpunishment. Communist systems obtained this

128 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

information through a combination of mecha-nisms, penetrating virtually every group withinsociety—youth, workers, teachers, peasants,and sometimes even the family unit. No orga-nization was allowed to exist outside the party.Mass acquiescence was thus sustained througha combination of fear, the penetration and at-omization of society, and material inducements.

Most noncommunist one-party regimes aresignificantly less coercive (Gandhi 2008), buttheir mechanisms for obtaining citizen acqui-escence are similar to those in more repres-sive regimes, in that state resources are used toreward the loyal and punish the disloyal. Thedenser the party’s organizational networks tomonitor and sanction citizens, and the more itmonopolizes valuable resources, the more ca-pable a one-party regime is of trapping citizensinto supporting the system (Magaloni 2006). Asa result, citizens’ support of the regime can bean informative signal of the regime’s stability.Citizens have an incentive to actively supportthe regime only if they expect it to last and tocontinue distributing privileges (Kricheli 2008)and if they expect to be punished if they de-fect (Diaz-Cayeros et al. 2001). This explainswhy one-party regimes normally invest a greatdeal of resources in winning elections with hugemargins and in generating large turnout evenwhen elections are not competitive (Simpser2005, Magaloni 2006, Blaydes 2009, Malesky& Schuler 2009). Supermajoritarian electionoutcomes and high turnout generate an imageof invincibility that works to dissuade poten-tial elite challenges, particularly those comingfrom powerful party officials. Unity within theone-party regime is hence deeply intertwinedwith the party’s capacity to mobilize the masses(Geddes 2006, 2008; Magaloni 2006).

In addition to requiring a strong party orga-nization, one-party regimes must solve criticalagency and moral-hazard problems on the partof the party cadres to effectively mobilize vot-ers. Once it is certain that the dictator’s partywill win, the party cadres do not necessarilyhave an incentive to invest time, effort, and or-ganizational resources in distributing rents tothe citizenry in order to generate high turnout

and supermajorities. If left unchecked, partycadres will have an incentive to free-ride byrunning on the party ticket, gaining access topower and spoils, and taking much of the piefor themselves.

Blaydes (2009) provides a fascinating ac-count of how Egypt’s one-party regime solvedthese problems using a semiauction system:“elections in Egypt closely resemble an all-payauction with bidders (parliamentary candidates)paying for a shot at the prize (the parliamen-tary seat). The bid that candidates pay is thecost of the electoral campaign, which is not fi-nanced by the hegemonic party” (Blaydes 2009,p. 15). This semiauction system entices votersto support candidates who are seen as closer tothe regime, and to whom they are connectedby family, clan, tribe, village, or personal rela-tionships (Lust-Okar 2006, Malesky & Schuler2008, Masoud 2008, Shehata 2008). In Mexico,the ruling party’s central leadership controlledthe nomination processes and, owing to asystem of nonreelection for all competitive of-fices, the party could induce strong disciplinefrom subnational office-seekers who had an in-centive to align with the party leadership andwith the president to obtain access to futurerent-seeking positions. Langston’s (2001, 2006)work persuasively shows that this regime beganto crumble when the leadership lost control ofthe nomination process.

By rewarding with more power and moreprivileges those who work harder for theparty—those who mobilize voters, fill theparty’s rallies, spy on others, and keep theirdistricts free of protests—the system becomesincentive-compatible. The ruling party therebylays the costs of popular mobilization at electiontime upon elite office seekers who are willingto put in effort, resources, and organizationalskills to gain access to state-controlled privi-leges (Lazarev 2005; Lust-Okar 2005, 2006).

The resulting support of the masses can fur-ther be used to counter threats from the mili-tary, which, according to Geddes (2006, 2008),represents the most formidable threat to dic-tators. She argues that the creation of a partyreduces the probability of successful coups for

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 129

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

two reasons: First, the party works to increasethe number of citizens who have something tolose from the ouster of the dictator; second, theparty machine can be employed to mobilize cit-izens in street protests at the time of a coup.

Autocrats’ ability to use the masses tocounter threats to their stability is therefore in-timately tied to their ability to gain mass sup-port via the party machine. If so, a one-partyregime’s durability should depend on its accessto resources to be distributed to the people inreturn for their support. If the regime controlsnatural resources or other economic means, itshould be able to increase social spending, mo-bilize the masses, and thereby increase its sur-vival prospects (Morrison 2009). If, however,the ruling party weakens and opposition leadersgain access to such resources, the party’s abilityto mobilize the masses will be hindered, and theregime will be destabilized (Greene 2002, 2007;Lawson 2002; Langston 2006). In these cases,political cooperation among different opposi-tion groups to dislodge the ruling party is morelikely (Arriola 2008).

Availability of economic resources alsodecreases the probability of coups (Londregan& Poole 1990) and of political destabilization(Fearon & Laitin 2003, Goldstone et al. 2003,Collier & Hoeffler 2004, Hegre & Sambanis2006). Correspondingly, higher levels of percapita income and stronger economic growthare associated with authoritarian stability(Haggard & Kaufman 1995, Cox 2008, Geddes2008, Kricheli 2008, Magaloni & Wallace2008). When dictators have the resourcesto induce cooperation from powerful groupswithin the elite and to fund a patronage systemto co-opt the citizens, the state remains stable.When they lack these resources, they “cannotpay their civil servants (who may therefore turnto corruption) or their armed forces (who maythen use their weapons to pay themselves)”(Bates 2008a, p. 5).

Analogously, scholars have also establisheda link between one-party regimes and highereconomic performance (Keefer 2007, Gandhi2008, Gehlbach & Keefer 2008, Wright 2008c).Yet the mechanisms underlying this link remain

unsettled in the literature. Some suggest thatone-party autocracies grow more than do othertypes of autocracies because they are more sta-ble, which lengthens rulers’ time horizons andreduces their incentives to plunder the econ-omy (Olson 1993, Wright 2008c). Others ar-gue that one-party dictatorships grow more be-cause their institutions are more constraining,and capital owners face a lower risk of confisca-tion (Gandhi 2008, Gehlbach & Keefer 2008,Wright 2008c). Moreover, it remains puz-zling that most single-party regimes have beenmarkedly populist and often confiscate the as-sets of the rich instead of protecting their prop-erty rights to encourage investment (Magaloni2006, Haber et al. 2003). Finally, the directionof the causal relation between economic growthand one-party rule is unclear. Are developmentand wealth causes of autocratic parties, whichin turn make dictatorships more stable, or arethey consequences of one-party rule? At thevery least, access to economic resources shouldnot be taken as completely exogenous to regimetype, as it is likely to be influenced by the typeof institutions dictators establish.

THE PARTY’S ORIGINS

The mere fact that single parties improve dicta-tors’ survival prospects does not necessarily en-tail that dictators will opt to create such parties.Nor does it entail that parties emerge becausethey serve this function. Using Elster’s (1982)terms, these are functionalist explanations thatexpose the functions served by single parties butdo not necessarily explain their causes.

Functionalist theories of single-party ruleleave us with many open questions. It is notclear whether autocrats are aware of the bar-gaining and mobilizing functions of ruling par-ties, and whether these functions play an im-portant role in an autocrat’s decision to fostera ruling party. Even if dictators are aware ofthese functions, they might opt to create othertypes of institutions that serve similar functions.For example, Haber et al. (2003) suggest thatdictators can solve the credible-commitmentproblem through social networks and through

130 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

intermarriage between the property class andthe ruling class, which is fairly typical in“personalist” regimes. Why dictators opt forthe creation of a party rather than pursuingthe personal-networks strategy highlighted byHaber et al. is not fully explained by the ex-tant literature on one-party regimes. Moreover,sustaining a thick party organization burdensthe autocrat with high costs (Belova & Lazarev2007) that may outweigh its benefits. We needa better understanding of the conditions un-der which creating and sustaining a party is anachievable and worthwhile strategy for the dic-tator, compared to other possible strategies, in-cluding ruling through personal connections orthrough kinship ties.

Examining the conditions that foster thecreation of one-party regimes might also en-able us to overcome the endogeneity problemsassociated with contemporary analyses of one-party rule. The mere empirical association be-tween one-party regimes and higher survivalprospects does not necessarily imply that par-ties actually increase autocrats’ stability. If one-party regimes are more likely to be consti-tuted when autocrats are more stable, then itmight well be the case that the correlation be-tween one-party regimes and higher survivalprospects is mostly explained by this initial se-lection effect.

If so, when are one-party autocracies likelyto be established? Are they more common af-ter the fall of democracy or after the fall of an-other type of autocracy? To provide insight intothese issues, the estimated transition matrix ofregime transformations among 169 countriesfrom 1950 to 2006 is displayed in Table 1.This matrix was estimated by first finding thesingle-period probabilities of a transition fromone regime type to another based on the exist-ing dataset; and second, treating these proba-bilities as determining a Markov process fromone regime into another occurring through thecourse of half a century. The elements in thematrix therefore represent the percentage ofregimes from one type (rows) that will trans-form to regimes from another type (columns)during this 50-period estimated process. The T

able

1E

stim

ated

regi

me

tran

siti

onm

atri

x,19

50—

2006

Tra

nsit

ions

Ori

gina

lre

gim

ety

peT

oan

arch

yT

om

onar

chy

To

mili

tary

To

sing

lepa

rty

To

dom

inan

tpa

rty

To

dem

ocra

cyT

otal

tran

siti

ons

Stab

ility

Tot

alA

narc

hy–

3.9%

23.5

%3.

9%33

.3%

35.3

%23

.18%

76.8

2%10

0%2

122

1718

5116

922

0M

onar

chy

0.0%

–63

.6%

9.1%

27.3

%0.

0%1.

50%

98.5

0%10

0%0

71

30

1172

373

4M

ilita

ry30

.4%

2.2%

–7.

6%27

.2%

32.6

%7.

31%

92.6

9%10

0%28

27

2530

9211

6512

57Si

ngle

-par

ty8.

8%0.

0%38

.6%

–33

.3%

19.3

%4.

14%

95.8

610

0%5

022

1911

5713

2113

78D

omin

ant-

part

y17

.5%

0.0%

23.8

%30

.2%

–28

.6%

5.04

%94

.96

100%

110

1519

1863

1188

1251

Dem

ocra

cy12

.1%

0.0%

67.2

%1.

7%19

.0%

–1.

90%

98.1

0%10

0%7

039

111

5829

9130

49

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 131

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

Table 2 Transitions to one-party rule

Original regimetype

To singleparty

To dominantparty

To one party (singleor dominant)

Anarchy 6.67% 22.67% 28.36%2 17 19

Monarchy 3.33% 4% 5.97%1 3 4

Military 23.33% 33.33% 47.76%7 25 32

Single party – 25.33% –19

Dominant party 63.33% – –19

Democracy 3.33% 14.66% 17.91%1 11 12

Total 100% 100% 100%30 75 67

number of observations in each category is writ-ten below each percentage. Table 2 presentsthe same information but focuses only on thetransitions to one-party rule, specifying the per-centage of transitions from each regime typeout of the overall number of transition to one-party rule. Importantly, the figures in both ta-bles take into account the fact that one regimecan transform into another and then transforminto a third type of regime, and so forth.

Tables 1 and 2 indicate that one-party ruleis not likely to emerge out of a single typeof regime; instead, they suggest four commonpaths to one-party rule. We suggest that eachof these different paths entails a different com-bination of top-down versus bottom-up forces,and depends on how these forces interact withinternational forces and changing internationalconditions.

The first path is the path from military rule:33.33% of dominant-party regimes and 23.33%of the single-party regimes established during1950–2006 emerged out of military dictator-ships. This route to the emergence of one-party dictatorship is mostly driven by top-downforces. Its logic corresponds to Geddes’ (2008)hypothesis that military autocrats often cre-ate political parties to mobilize the masses andthereby counterbalance military threats to their

stability. The fact that one-party regimes arelikely to emerge as a strategic decision on thepart of dictators also corresponds to Smith’s(2005) and Gandhi & Przeworski’s (2006) hy-pothesis that suggests that dictators resort to thecreation of political parties when they confrontstrong oppositions. The transition from a mili-tary (or more personalist) dictatorship to a partyregime is understood as a way to accommodateconcessions to the opposition in an effort tominimize threats to the dictator’s stability.

The second path to one-party rule is thepath from anarchy: 22.67% of dominant-partyregimes and 6.67% of single-party regimes es-tablished during 1950–2006 were establishedafter a period of anarchy or civil war. Hunt-ington (1968) first highlighted this route tothe emergence of one-party regimes, suggest-ing that these regimes are the product of so-cial revolutions or independence movements:“The more intense and prolonged the struggleand the deeper its ideological commitment, thegreater the political stability of the one–partysystem” (p. 425). This is a bottom-up path toone-party rule.

Why does anarchy lead to the establish-ment of one-party rule as opposed to the es-tablishment of a different regime type? Onepossibility, which is drawn from the literatureon civil war, is that anarchy transforms intoone-party dictatorship when one dominantforce is able to eliminate the opposition mili-tarily, or when the population is ethnically con-centrated (Bates 2008a,b). If, on the other hand,a minority has a significant advantage in accessto military resources or economic resources tofund violence, this minority might be able todominate and rule by fear and terror (Collieret al. 2007). In these cases, it might be morelikely that anarchy gets resolved through theestablishment of a military dictatorship ratherthan a party dictatorship. Democracy might re-sult, instead, when military forces are more bal-anced (Wantchekon 2004, Przeworski 2009).Another possibility is that one-party dictator-ships arise out of anarchy as a pact amongwarlords to create political order after thesewarlords realize that they would be better off

132 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

colluding to share power than continuing tofight. Magaloni (2006) argues that this was thepath of emergence of the Mexican one-partyregime.

The third path to one-party rule is the pathfrom democracy: 17.91% of one-party regimeswere established after the fall of democracy.The regimes of President Hugo Chavez inVenezuela and of President Vladimir Putin inRussia are two of the best-known examples.Although democracies are most likely to col-lapse in the hands of the military (67.2% of thetransitions from democratic rule), they oftensuccumb to dominant-party autocracy (19%).This tendency of democracy to collapse todominant-party autocracy rather than to single-party or military regimes is mostly a post–ColdWar phenomenon. In the period between 1950and 1989, there were 58 collapses of democraticregimes, 67% of which transformed to militarydictatorship. After the end of the Cold War, onthe other hand, there were only 14 democraticbreakdowns, and the overwhelming majority ofthese led to dominant-party dictatorship. In-terestingly, during the same period, some au-thoritarian leaders in post-communist regimesmanaged to adapt to democracy and return topower using their access to state resources torebuild their supporting coalitions (Grzymala-Busse 2002, 2007).

The fourth path to one-party rule is fromanother type of one-party rule, that is, froma dominant-party regime to a single-partyregime or vice versa. These transitions areprocesses of liberalization or antiliberalizationthrough which dictators modify the existingrules of political contestation while remainingin power. Transitions from dominant-partyto single-party regimes were common in theearly period of decolonization in many Africancountries, and these mostly occurred after inde-pendence leaders won overwhelming victoriesin the first independent multiparty electionsand subsequently chose to ban the opposition.Most of these transitions to single-partydictatorships correspond to the bottom-uproute of party creation highlighted by Hunt-ington (1968). Transitions from single-party

dictatorships to dominant-party regimes, onthe other hand, resulted from the legaliza-tion of multiparty competition and were mostfrequent in the 1990s both in Africa and the for-mer Soviet Republics. Parties like the ChamaCha Mapinduzi in Tanzania, the GaboneseDemocratic Party, the Kenya African NationalUnion, and the Cameroon People’s DemocraticMovement, to name just a few, ruled for yearswhile proscribing the opposition, and decidedto allow multiparty elections only after 1990.

In addition to the four paths to one-partyrule, Tables 1 and 2 also suggest some insightsinto the collapse of one-party rule. In con-trast to the common view that one-party ruleleads to democratization, one-party regimesseldom democratize: Only 24.17% of the tran-sitions from one-party rule are to democ-racy. Instead of democratizing, most of thesingle-party regimes fall prey to military coupsor broaden political competition to becomedominant-party regimes: 38.6% of the tran-sitions from single-party regimes are to mili-tary regimes and 33.3% are to dominant-partyregimes, while only 19.3% are to democracy.Moreover, dominant-party regimes are mostlikely to transform to single-party regimes, notto democratic regimes: 30.2% of the tran-sitions from dominant-party regimes are tosingle-party regimes, while only 28.6% are todemocratic regimes. In fact, compared to mili-tary rule and to anarchy, one-party regimes arethe least likely to transform to democracy aftertheir collapse.

These findings suggest that transitions fromone type of authoritarianism to another de-serve more scholarly attention. The regime-transitions literature has focused mostly ontransitions from authoritarian rule to demo-cratic rule or vice versa (e.g., O’Donnell et al.1986; Przeworski et al. 2000; Acemoglu &Robinson 2001, 2006, 2008; Boix 2003; Boix& Stokes 2003; Epstein et al. 2006). However,members of the ruling clique can also respondto the weakening of the current regime or tomass mobilization by establishing a new dicta-torship. Transitions from one type of author-itarian rule to another were indeed the most

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 133

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

Table 3 Simulated long-term regime distributionsa under changing geopolitical conditions

Time period Anarchy Monarchy Military Single party Dominant party DemocracyDecolonization: 1950–1964 2.79% 9.22% 15.97% 17.13% 16.01% 38.89%Cold War: 1965–1988 2.3% 5.2% 28% 17% 8.4% 40%Post Cold War: 1989–2006 3.6% 8.2% 5.2% 0% 26.2% 57%

aRegime distributions come from simulating Markov transition frequencies obtained for the three historical periods. The base frequency vector is theaverage regime distribution of the period 1950–2006. Simulations come from repeating each Markov transition matrix 50 times.

common form of regime change during the pasthalf century: Out of the total number of regimetransitions during 1950–2006, 43% were tran-sitions from dictatorship to dictatorship, whileonly 27% were from democracy to dictatorshipand 31% from dictatorship to democracy.

Yet because of its focus on regime changefrom autocracy to democracy and vice versa, theregime-transitions literature cannot provide atheory of why dictators are most commonly re-placed by new dictators, or of why transitionsto another type of autocracy are more likelythan transitions to democracy under certainconditions but not under all conditions. Thenext section suggests that changing geopoliticalconditions—a factor commonly ignored in thedemocracy literature—need to be taken morefully into account to understand transitions ingeneral and transitions from and to one-partydictatorship in particular.

CHANGING GLOBAL ANDGEOPOLITICAL CONDITIONSAND DEMOCRATIZATION

The origins, stability, and collapse of one-party regimes cannot be treated independentlyof global forces and of changing geopoliti-cal conditions. Arguably, global and interna-tional forces can influence the stability levelsone-party regimes enjoy as well as the likeli-hood that a collapsing regime will transforminto a one-party autocracy. Moreover, changesthat influence the entire global community—e.g., innovations in the technology of ruling, theemergence of a new discourse about elections,or the spread of the international media—mightalso encourage global trends in the spread ofone-party rule.

To better understand the change in theglobal and geopolitical trends governingregime transitions to and from one-party rule,we examine, using Markov simulations, how thespread of one-party rule would have looked ifthe global and geopolitical trends existing inone of three subperiods—before, during, andafter the Cold War—had prevailed for half acentury. We estimate three alternative Markovchain transition probabilities: one for the yearsof decolonization during 1950–1964; a secondfor the height of the Cold War during 1965–1988; and a third for the post–Cold War pe-riod of 1989–2006. We then apply the transi-tion probabilities in each period to the averagedistribution of political regimes in the period1950–2000,3 and repeat the Markov process for50 years, yielding different distributions of po-litical regimes that reflect how the world orderwould have looked if one of these geopoliticalorders had prevailed for 50 years. The result-ing hypothetical distributions of different typesof regimes are presented in Table 3. The en-tries in this table represent the percentage ofeach regime type under each relevant geopolit-ical order.

The results presented in Table 3 stronglysupport the hypothesis that the frequency ofone-party dictatorships has been subject to dis-parate trends before, after, and during the ColdWar. If the geopolitical trends existing duringthe decolonization period had continued to ex-ist, the future would have looked rather het-erogeneous: About 39% of the countries would

3The average distribution of regimes is as follows: 39%democracies, 17% single-party, 16% dominant-party, 16%military, 3% anarchy.

134 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

have been democracies, 16% military dicta-torships, 17% single-party dictatorships, 16%dominant-party regimes, and 9% monarchies.On the other hand, if the geopolitical trends ex-isting during the Cold War had existed for thelast half century, most of the autocracies wouldhave been military regimes, followed distantlyby single-party dictatorships. Dominant-partyregimes would not have been especially com-mon. Last, if the geopolitical trends of the post–Cold War era had existed for the last half cen-tury, dominant-party regimes would have beenthe most common type of authoritarianism.Single-party regimes would have completelydisappeared, and military dictatorships wouldhave represented only 5% of the regimes. Thepost–Cold War era should thus unquestion-ably be associated with the spread of dominant-party autocracies or “electoral authoritarian”regimes.

What shapes these international trends ofregime transitions? Bates (2001) suggests thatduring the Cold War, dictators strategicallyplayed the different international interests totheir advantage, gaining access to foreign andmilitary aid without having to make policy con-cessions in terms of liberalization or democrati-zation. As such, Cold War conditions were par-ticularly conducive to the emergence of closeddictatorships, and in particular to military dicta-torships, which strategically used the commu-nist threat to get funds from international fi-nancial institutions and from the United Statesto repress their opponents. Communist one-party regimes, for their part, relied on the SovietUnion to sustain their economies.

The end of the Cold War, by contrast, hasfavored the expansion of both democracy andelectoral authoritarianism. Dictators interestedin gaining access to international funds possess astrong interest in adopting multiparty electionsbecause donors generously reward dictatorswho hold elections (Kricheli 2009). Globaleconomic forces also played an importantrole in changing autocrats’ incentives to holdelections: In the 1970s, developing countrieswere negatively affected by higher oil prices,which reduced demand for their exports in rich

countries. Many developing countries overbor-rowed to continue spending, and the resultingdebt crisis of the 1980s compelled developingcountries to retrench their spending, adjusttheir finances, liberalize trade, and embrace themarket. The change in economic policies andthe continued pressure of international finan-cial institutions and donors to adjust macro-economic policies triggered the collapse of pa-tronage networks that had previously sustainedauthoritarian regimes. In the face of thisweakening of the state, the loss of economicresources that resulted from economic lib-eralization, and the sustained deteriorationof living conditions, dictators’ opponentsstrengthened. In some cases, weakening auto-crats were compelled to embrace the marketand democracy simultaneously (Przeworski1991, Haggard & Kaufman 1995). In othercases, autocrats responded by liberalizing theregime and allowing multiparty competitionwhile continuing to hold power through thecorruption of electoral processes.

The literature examining these changingtrends in the spread of dominant-party ruleis still in its infancy. Research has focusedmainly on international actors’ influence on anautocrat’s decision to hold elections or allowelection monitoring, and on their influence ondemocratization (Bates 2001, Levitsky & Way2005, Brinks & Coppedge 2006, Gleditsch &Ward 2006, Escriba-Folch & Wright 2008,Mainwaring & Perez-Linan 2008, Beaulieu& Hyde 2009, Kricheli 2009). We note fourchallenges faced by this literature.

One challenge associated with identifyingthe links between international factors, policymaking, and democratization is to better spec-ify the strategic behavior of the internationalcommunity, in particular foreign donors. Whydo donors reward multiparty elections so gen-erously if autocrats continue to rule by cor-rupting electoral processes and by rigging elec-tions? Kricheli (2009) suggests one avenue foranswering this question: Donors for the mostpart are not interested in promoting democ-racy but rather care about political stability,which shapes the return on their investments.

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 135

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

According to Kricheli, autocrats holding elec-tions signal their stability, not their democraticcommitment, and thus get rewarded. But morework is needed to uncover how and under whatconditions international organizations and in-stitutions might be able to sanction dictatorsand promote democracy and when they arelikely to fail.

A second challenge is the problem of endo-geneity. The type of authoritarian regime ex-isting in a country cannot be considered inde-pendent from international factors. The type ofdictatorship adopted can be powerfully shapedby donors’ behavior and their willingness tosanction (Kricheli 2009). Przeworski (2009) ar-gues even further that regime types are epiphe-nomena, and thus the conditions that fostertheir creation, instead of the regimes them-selves, should be the focus of our analysis.

A third challenge is determining the degreeto which authoritarian policy making andregime transitions are influenced by domesticversus international forces. Are they mostlyshaped by international factors (Levitsky &Way 2005, Brinks & Coppedge 2006, Gleditsch& Ward 2006, Hyde & Marinov 2008, Wright2008b), by internal dynamics (Geddes 2006,2008; LeBas 2006; Lust-Okar 2006; Magaloni2006, 2008; Greene 2007, 2010; Arriola 2008;Cox 2008), or by the interaction of domesticand international factors (Solinger 2001,Bjornlund 2004, Hyde 2006)?

A fourth challenge is that the simultane-ous expansion of electoral authoritarianism anddemocracy in the contemporary period raisesconcerns about the link between political com-petition under authoritarianism and democra-tization. Indeed, the extent to which multipartyelections in autocracies are likely to induce de-mocratization has been contested in the lit-erature (Gandhi & Lust-Okar 2009). On theone hand, scholars have emphasized how au-thoritarian elections might transform citizens’propensities to participate and augment theirexpectations of government accountability (Pei1995, Shi 1999, Li 2003, Lindberg 2006a,b,Birney 2007, Wang & Yao 2007); resultin gradual institutional transformations that

prepare for the eventual victory of the demo-cratic opposition (Eisenstadt 2004, Howard &Roessler 2006, Lindberg 2006c, Roessler &Howard 2008); or encourage democratizationafter political breakdown (Bratton & van deWalle 1997, Bunce & Wolchik 2006, Beissinger2007, Brownlee 2009), all of which, in turn, in-crease the possibility of democracy. Yet on theother hand, scholars have also questioned thelink between political competition under au-thoritarianism and democratization, suggestingthat dominant-party regimes might be ratherresilient to democratization (Lust-Okar 2006,2009; Brownlee 2007; McCoy & Hartlyn 2007,2009; Kricheli 2009; Greene 2010).

GUNS AND VOTES

We conclude by reflecting on the fundamen-tal problem of autocratic political order. Theperception of autocrats as rulers who providerents only to the elites while completely ne-glecting the people seems misguided. In theface of simultaneous threats to their stabilityfrom within the elites and from within themasses, choosing to distribute rents only to theelites is not an optimal strategy from the dicta-tor’s perspective (Bueno de Mesquita & Smith2009, Kricheli & Livne 2009). Autocrats thushave to calculatedly distribute resources be-tween the masses and the elites. They face thedilemma of how to efficiently balance their re-sources between guns and votes so as to max-imize their survival prospects. When the au-tocrat bestows too much power on the elites orrelies too much on the military, he becomes vul-nerable to threats from within his ruling cliqueand must mobilize the voters to counterbalancethese threats. Yet when he bestows too muchpower on the citizens, he risks electoral defeat,and will need the military to enforce electoralfraud to ensure his survival.

Although relatively little is known aboutautocrats’ ability to overcome the guns-versus-votes dilemma, scholars agree on importantimplications of its existence. Dictatorial po-litical order is ultimately based on coercioneven when voters can choose between political

136 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

alternatives (Przeworski 2009). Thus, a criticalmoment that defines the passage from author-itarianism to democracy is the one when nopolitical power can reverse the elections’ results(Przeworski 1985). Ultimately, therefore, partydictatorships can only be defeated throughelections if voters support the opposition andif the military does not enable the dictator tosteal the elections from them. Magaloni (2009)argues that when the ruling party steals theelections’ results despite voters’ support of theopposition, the future of the regime cruciallydepends on the armed forces’ strategy: Theymight back the ruling party and threaten torepress the population; oust the rulers througha coup and rule on their own; or side with themasses, in which case democracy can emergeas a result of a “civil revolution.” The militaryshould thus be considered a strategic playerwho can act self-interestedly against the regimeor in support of the masses (Geddes 2006,2008; Magaloni 2009; Acemoglu et al. 2009;Przeworski & Gandhi 2009).

Electoral fraud is common in many autocra-cies (Lehoucq & Molina 2002; Schedler 2002,2006; Lehoucq 2003; Simpser 2005, 2008;Simpser & Donno 2008). However, the factthat the armed forces will not necessarily optto support the regime in cases of electoral fraudmight also explain why autocrats do not alwaysfollow this strategy. If the military’s support isnot guaranteed, electoral manipulation is riskybecause it might induce the masses to challengethe regime and facilitate the mobilization of theopposition (van de Walle 2002, Thompson &Kuntz 2004, Lindberg 2006a, Beissinger 2007,Donno 2007, Tucker 2007, Bunce & Wolchik2009, Przeworski & Gandhi 2009).

When the armed forces opt, however, tosupport the regime and ensure the dictator’selectoral victory, electoral violence becomesnecessary. Many of the contemporary author-itarian elections are afflicted with hideous vio-lence against voters who accuse the regime ofelectoral fraud. The 2009 political crisis in Iran,the 2008 presidential elections in Zimbabwe,and the 2005 general elections in Ethiopia areexamples of such cases.

Soldiers matter for authoritarian stability,but citizens matter as well. Military officers aremore likely to defect the regime if they per-ceive the masses as being capable of orchestrat-ing a revolution, even a peaceful one.4 Citizenscan sometimes defeat soldiers. As the chief ofthe Eastern German police, Erich Mielke, saidto the party leader, Erich Honecker, in the af-termath of a demonstration joined by a mil-lion citizens: “Erik, one just cannot beat thatmany people” (Przeworski 1991). The samelogic was behind the military’s defection dur-ing the Orange and Rose Revolutions. In thesecases, regimes were weakened and ultimatelydefeated by mass revolts aimed at ousting dicta-tors who had stolen elections. Weingast (1997),Fearon (2006), and Magaloni (2009) explore thefactors that allow societies to coordinate againstthis type of abuse.

Many open questions regarding autocrats’need of both guns and votes still remain. Theliterature has not yet fully explained when au-tocrats are likely to be threatened by the elitesor by the masses; when they are likely to dis-tribute more rents to the masses at the expenseof the elites; or when they are likely to do theopposite. The relationships between the mili-tary and the ruling party, as well as the strate-gies civilian leaders follow to subordinate themilitary to their authority, are not well under-stood, although they seem to differ across one-party regimes (Finer 1962, Kolkowicz 1967,Huntington 1975, Perlmutter & LeoGrande1982). This should be an important avenue forfuture research.

CONCLUSION

The literature on one-party rule highlightstwo mechanisms whereby ruling parties canincrease autocrats’ survival prospects: Rulingparties mobilize the masses and facilitate thebargaining process with the elites. However,many puzzles regarding the link between ruling

4This part of the review was crucially influenced by a con-versation with Adam Przeworski.

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 137

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

parties and authoritarian stability remain un-solved. To fully understand one-party regimes,a comprehensive theory of the conditions thatfoster the rise and fall of one-party regimes isneeded.

Such a comprehensive theory will need toaddress four sets of questions. The first in-cludes questions regarding the interaction be-tween mass mobilization and elite bargaining.We need to understand how autocrats solvethe guns-versus-votes dilemma and distributeresources between the elites and the masses soas to maximize their survival prospects.

The second set of questions relates to theorigin of regimes of all types and of one-partyregimes in particular. Transitions from one typeof authoritarian regime into another deservemore scholarly attention. Moreover, uncover-ing the conditions that foster the establish-ment or the collapse of one-party regimes will

enable scholars to fully understand why one-party regimes emerge and why they are morestable than are other forms of authoritarianism.

The third set of questions relates to the rela-tionship between democracy and one-party ruleand the variation among party regimes in thiscontext. Do elections under authoritarianismpromote democratization or instead foster au-thoritarian stability? Why are dominant-partyregimes more likely to transform to democracythan single-party regimes?

The fourth and last set of questions ad-dresses the role played by international andgeopolitical forces in authoritarian policy mak-ing and in regime transitions. We need a deeperunderstating of the global forces that influencethe policy decisions made by one-party auto-crats and the stability of their regimes, as wellas a deeper understanding of the interaction be-tween these forces and domestic forces.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings thatmight be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Bob Bates, Alberto Diaz-Cayeros, Yair Livne, and one anonymous reviewerfor their helpful comments.

LITERATURE CITED

Acemoglu D, Robinson J. 2001. A theory of political transitions. Am. Econ. Rev. 91:938–63Acemoglu D, Robinson J. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. New York: Cambridge Univ.

PressAcemoglu D, Robinson J. 2008. Persistence of power, elites, and institutions. Am. Econ. Rev. 98(1):267–93Acemoglu D, Ticchi D, Vindigni A. 2008. A theory of military dictatorships. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. Work. Pap.

No. 13915Ames B. 1970. Bases of support for Mexico’s dominant party. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 64(1):153–67Arriola LR. 2008. Between coordination and cooptation: the opposition’s dilemma in Africa. PhD thesis, Dep. Polit.

Sci., Stanford Univ.Arriola LR. 2009. Patronage and political stability in Africa. Comp. Polit. Stud. 42(10):1339–62Bates RH. 2001. Prosperity and Violence. New York: NortonBates RH. 2008a. State failure. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 11:1–12Bates RH. 2008b. When Things Fell Apart: State Failure in Late Century Africa. New York: Cambridge Univ.

PressBaturo A. 2007. Presidential succession and democratic transitions. Inst. Int. Integr. Stud. Work. Pap. #209Beaulieu E, Hyde S. 2009. In the shadow of democracy promotion: strategic manipulation, international

observers, and election boycotts. Comp. Polit. Stud. 42(3):392–415

138 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

Beissinger MR. 2007. Structure and example in modular political phenomena: the diffusion of Bulldozer/Rose/Orange/Tulip Revolutions. Perspect. Polit. 5(2):259–74

Belova E, Lazarev V. 2007. Why parties and how much? The Soviet state and the party finance. Public Choice130(3–4):437–56

Birney M. 2007. Can local elections contribute to democratic progress in authoritarian regimes? Exploring the politicalramifications of China’s village elections. PhD thesis. Dep. Polit. Sci., Yale Univ.

Bjornlund E. 2004. Beyond Free and Fair: Monitoring Elections and Building Democracy. Princeton, NJ: WoodrowWilson Cent. Press

Blaydes L. 2006. Who votes in authoritarian elections and why? Vote buying, turnout, and spoiled ballots in contemporaryEgypt. Presented at Annu. Meet. Am. Polit. Sci. Assoc., Philadelphia, PA

Blaydes L. 2009. Competition without Democracy: Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. Unpub-lished book manuscript

Boix C. 2003. Democracy and Redistribution. New York: Cambridge Univ. PressBoix C, Stokes S. 2003. Endogenous democratization. World Polit. 55:517–49Boix C, Svoliky M. 2008. The foundations of limited authoritarian government: institutions and power-sharing in

dictatorships. Presented at Conf. Dictatorships: Their Governance and Social Consequences, PrincetonUniv., Princeton, NJ

Bolotnyy V, Magaloni B. 2009. Authoritarian Regimes Classification. DatabaseBratton M, van de Walle N. 1997. Democratic Experiments in Africa. New York: Cambridge Univ. PressBrinks D Coppedge M. 2006. Diffusion is no illusion: neighbor emulation in the third wave of democracy.

Comp. Polit. Stud. 39(4):463–89Brownlee J. 2007. Authoritarianism in an Age of Democratization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. PressBrownlee J. 2009. Harbinger of democracy: competitive elections before the end of authoritarianism. See

Lindberg 2009, pp. 128–47Bueno de Mesquita B, Smith A, Siverson RM, Morrow JD. 2003. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge,

MA: MIT PressBueno de Mesquita B, Smith A. 2009. Political survival and endogenous political change. Comp. Polit. Stud.

42(2):167–97Bunce V, Wolchik S. 2006. Favorable conditions and electoral revolutions. J. Democr. 17(4):5–18Bunce V, Wolchik SL. 2009. Opposition versus dictators: explaining divergent election outcomes in post-

Communist Europe and Eurasia. See Lindberg 2009, pp. 246–68Collier P, Bates R, Hoeffler A, O’Connell S. 2007. Endogenizing syndromes. In The Political Economy of Economic

Growth in Africa, 1960–2000, ed. B Ndulu, P Collier, R Bates, S O’Connell, pp. 391–418. Cambridge,UK: Cambridge Univ. Press

Collier P, Hoeffler A. 2004. Greed and grievance in civil wars. World Bank Policy Res. Pap. 2355Cox G. 2008. Authoritarian elections and leadership succession, 1975–2000. Presented at Annu. Meet. Am. Polit.

Sci. Assoc., Toronto, Can.Debs A. 2007. On dictatorships. PhD thesis, Dep. Econ., Mass. Inst. Technol.Diamond L. 2002. Thinking about hybrid regimes. J. Democr. 13(2):21–35Diaz-Cayeros A, Magaloni B, Weingast BR. 2001. Tragic brilliance: equilibrium party hegemony in Mexico. Work.

pap., Hoover Inst.Donno D. 2007. Partners in defending democracy: regional intergovernmental organizations and opposition mobiliza-

tion after flawed elections. Presented at Elections and Political Identities Conf., Yale Univ., New Haven,CT

Eisenstadt T. 2004. Courting Democracy in Mexico: Party Strategies and Electoral Institutions. New York:Cambridge Univ. Press

Elster J. 1982. Marxism, functionalism and game-theory: the case for methodological individualism. TheorySoc. 11:453–81

Epstein DL, Bates R, Goldstone J, Kristensen I, O’Halloran S. 2006. Democratic transitions. Am. J. Polit. Sci.50(3):551–69

Escriba-Folch A, Wright JG. 2008. Dealing with tyranny: international sanctions and autocrats’ duration. Work.Pap., Inst. Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals

www.annualreviews.org • Political Order and One-Party Rule 139

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

Fearon JD. 2006. Self enforcing democracy. Presented at Annu. Meet. Am. Polit. Sci. Assoc., Philadelphia, PAFearon JD, Laitin DD. 2003. Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97(1):75–90Finer SE. 1962. The Man on Horseback. New York: PraegerGandhi J. 2008. Political Institutions under Dictatorship. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. PressGandhi J, Przeworski A. 2006. Cooperation, cooptation, and rebellion under dictatorships. Econ. Polit. 18(1):1–

26Gandhi J, Lust-Okar E. 2009. Elections under authoritarianism. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 12:403–22Geddes B. 1999. What do we know about democratization after twenty years? Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2:115–44Geddes B. 2006. Why parties and elections in authoritarian regimes? Presented at Annu. Meet. Am. Polit. Sci.

Assoc., Washington, DCGeddes B. 2003. Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research Design in Comparative Politics. Ann

Arbor: Univ. Mich. PressGeddes B. 2008. Party creation as an autocratic survival strategy. Presented at Conf. Dictatorships: Their Gov-

ernance and Social Consequences, Princeton Univ., Princeton, NJGehlbach S, Keefer P. 2008. Investment without democracy: ruling-party institutionalization and credible commitment

in autocracies. Work. pap., Soc. Sci. Res. Netw.Gleditsch K, Ward M. 2006. Diffusion and the international context of democratization. Int. Organ. 60(4):911–

33Golder M. 2005. Democratic electoral systems around the world, 1946–2000. Elect. Stud. 24(2005):103–21Goldstone J, Marshall M, Bates R, Epstein D. 2003. State Failure Task Force Project, Phase III Report. McLean,

VA: Sci. Appl. Int. Corp.Greene KF. 2002. Opposition party strategy and spatial competition in dominant party regimes: a theory and

the case of Mexico. Comp. Polit. Stud. 35(7):755–83Greene KF. 2007. Why Dominant Parties Lose: Mexico’s Democratization in Comparative Perspective. New York:

Cambridge Univ. PressGreene K. 2010. The political economy of authoritarian single party dominance. Comp. Polit. Stud. 43(9) In

pressGrzymala-Busse AM. 2002. Redeeming the Communist Past: The Regeneration of Communist Parties in East-Central

Europe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. PressGrzymala-Busse AM. 2007. Rebuilding Leviathan: Party Competition and State Exploitation in Post-Communist

Democracies. New York: Cambridge Univ. PressHaber S. 2006. Authoritarian government. In Handbook of Political Economy, ed. BR Weingast, D Wittman,

pp. 693–707. New York: Oxford Univ. PressHaber SH, Maurer N, Razo A. 2003. The Politics of Property Rights: Political Instability, Credible Commitments,

and Economic Growth in Mexico. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. PressHadenius A, Teorell J. 2007. Pathways from authoritarianism. J. Democr. 18(1):143–56Haggard S, Kaufman RR. 1995. The Political Economy of Democratic Transitions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ.

PressHavel V. 1978. The power of the powerless. In Open Letters: Selected Writings 1965–1990 by Vaclav Havel,

pp. 125–214. London: Faber & FaberHegre H, Sambanis N. 2006. Sensitivity analysis of empirical results on civil war onset. J. Confl. Resolut.

50(94):508–35Howard MM, Roessler PG. 2006. Liberalizing electoral outcomes in competitive authoritarian regimes.

Am. J. Polit. Sci. 50(2):365–81Huntington SP. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. PressHuntington SP. 1975. The Soldier and the State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. PressHuntington SP. 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman: Univ. Okla.

PressHyde S. 2006. Observing norms: explaining the causes and consequences of internationally monitored elections. PhD

thesis, Dep. Polit. Sci., Univ. Calif. San DiegoHyde S, Marinov N. 2008. Does information generate self-enforcing democracy? The role of international election

monitoring. Presented at Int. Stud. Assoc. Annu. Conv., 49th, Bridging Multiple Divides, San Francisco,CA

140 Magaloni · Kricheli

Ann

u. R

ev. P

olit.

Sci

. 201

0.13

:123

-143

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Cal

ifor

nia

- Sa

n D

iego

on

01/1

2/15

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

ANRV412-PL13-07 ARI 6 April 2010 16:36

Keefer P. 2007. Governance and economic growth in China and India. In Dancing with Giants, ed. LA Winters,S Yusuf, pp. 211–42. Washington, DC: World Bank