pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.compmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/180320Legal_respo… ·...

Transcript of pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.compmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/180320Legal_respo… ·...

Draft Public Audit Amendment Bill, 2018

Response by Parliamentary Legal Advisers on comments and

proposals received during the public participation process

1. Introduction

This document is prepared with the purpose of highlighting and commenting on the legal

issues raised during the public participation process.

The following abbreviations are used:

AG- Auditor-General

AO- Accounting Officer1

AA- Accounting Authority

EA- Executive Authority

UIFW- Unauthorised, irregular and fruitless and wasteful expenditure

MFMA- Local Government Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003

PAA- Public Audit Act, 2004

PFMA- Public Finance Management Act, 1999

2. Constitutional Mandate

A number of the submissions received challenged the constitutional validity of empowering

the AG to issue a certificate of debt and to collect that debt.

Three broad arguments were presented. The first is that the AG is not empowered in terms

of the Constitution to issue such certificates or collect debts- the Constitution does not

specifically provide for this power. Secondly, those functions cannot be considered to be part

of the AG’s function to audit and report on financial management as per section 188 (1) and

(2) of the Constitution.

1 For purposes of this document the term is used interchangeably with Accounting Authority. The latter is represented by a board rather than a single person.

1

Lastly, to empower the AG to issue a certificate would encroach on the powers and functions

of other organs of state already tasked with debt recovery thereby threatening its

independence.

On a careful reading of section 188 (4) of the Constitution, our view is that the use of the

words “additional powers and functions”, when given its ordinary meaning, point to an

intention to empower the AG to do more than what section 188 specifically provides for. The

intention, in our view, could not have been to provide for the enactment of legislation to

merely regulate the audit and reporting functions. If this were the case the word “additional”

in relation to “powers and functions” would not be used. The provision would not have been

open-ended and would have read instead that national legislation must be enacted to give

effect to the manner in which the AG’s powers and functions in section 188(1)-(3) are

regulated. This view is supported by a consideration of other clauses in the Constitution

which, unlike this provision, state very specifically what national legislation must prescribe. 2

Notwithstanding that subsection (4) allows for additional powers and functions – other than

auditing and reporting- our view is that these additional powers must be shown to be

rationally connected to the primary function of the AG. Comparative international law

supports the view that debt recovery and/or remedial binding action can be performed by a

supreme audit institution. The Lima Declaration of 1977 which was adopted by the

International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions and which is considered the Magna

Carta of public auditing standards establishes that the principle of enforceability of the

findings of a supreme audit institution is a key element of public auditing. Whilst it does not

speak to recovery powers specifically it does state that, “to the extent the findings of the

Supreme Audit Institution are not delivered as legally valid and enforceable judgments, the

Supreme Audit Institution shall be empowered to approach the authority which is responsible

for taking the necessary measures and require the accountable party to accept

responsibility.” One can clearly read into this provision the power to issue a certificate

following an audit finding and the consequent financial recovery.

2 By way of example see section 215 (2) in respect of national, provincial and municipal budgets; section 217 (3) which speaks to a framework for procurement based on the Constitutional principles of procurement; section 219 (2) that speaks to national legislation establishing an independent commission to advise on specific salary related issues.

2

In our view the recovery of funds is directly linked to audit findings and give effect to the

findings which may otherwise be rendered meaningless by non-action. In this regard, the

additional powers promote the objectives of transparency and accountability.

The provision for additional powers and functions in subsection (4) is not unique to the AG

and also appears in respect of other Chapter 9 Institutions. The provision was the subject of

consideration in relation to the Public Protector in the so-called Nkandla judgment3. Here, the

Court stated that:-

“mediation, conciliation, negotiation and giving advice to a complainant regarding how best

to secure an appropriate remedy; bringing what appears to be an offence to the attention of

the prosecuting authority; referring a matter to an appropriate body or authority or making

suitable recommendations to remedy the complaint; and resolving any complaint by “any

other means that may be expedient in the circumstances”, are all regulatory and additional

powers. And they are consistent with and flow from the constitutional power “to take

appropriate remedial action” and provision for “additional powers and functions”.4

We are thus confident that the additional powers and functions related to the issuing of a

certificate is permissible in so far as it rationally connected to the duty to audit and can be

regarded as a tool to strengthen constitutional democracy.5

We further hold no legal objection to the AG being the responsible person for the actual debt

collection function. However, having regard to the resource and capacity constraints of the

AG we agree that this option is not feasible at present.

In respect of the encroachment argument, we agree that the AG can never usurp the powers

and functions of another organ of state and the power to issue a certificate and recover

funds cannot be done in a manner that impedes the independence or prevents an organ of

state from following its own lawful prescripts.

For this reason, the recovery mechanism must be designed in such a manner as to support

AO’s and AA’s by promoting compliance with existing financial management laws. The

3 Economic Freedom Fighters v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others; Democratic Alliance v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others (CCT 143/15; CCT 171/15) [2016] ZACC 11; 2016 (5) BCLR 618 (CC); 2016 (3) SA 580 (CC) (31 March 2016).4 See Nkandla judgment footnote 61.5 For more information on other international jurisdictions with recovery powers see Transparency International’s, “Overview of Countries’ Supreme Audit Institutions with Surcharge Powers” available at www.transparency.org

3

objectives of the additional powers is based on a model of deterrence and as an additional

line of final defence rather than an arrogation of functions and powers.

3. Accounting Officer/Accounting Authority includes “former” person(s) who held such posts

Concerns were raised that the inclusion of the word “former” in the definition of accounting

officer/authority would have the effect of making the Bill retrospective.

The policy intent was never to have retrospective effect and the inclusion of former

accounting officers is limited in the recovery process to only hold to account those AO’s or

members of an AA who have failed to act in terms of an audit report issued after the Bill has

come into operation.

Auditing by its very nature is a backward looking process. Accordingly, an audit report will

always speak to transactions that have occurred in the past. It is therefore possible that an

AO will be held to account in terms of the new Bill for transactions which occurred in the

financial year prior to the Bill coming into operation. However, the AO will only incur liability

in the event that he or she fails to take positive steps on receipt of an audit report that is

issued after the Bill becomes law. An AO will therefore not be issued with a certificate until

such time as he or she has had a full and complete opportunity to take the necessary legal

steps.

4. Definition of debtor and related risks

Many submissions questioned why the definition of debtor was limited to the AO/AA. The

concern was that an accounting officer may not necessarily be blameworthy for the loss

suffered and accordingly the definition should be extended to include responsible officials. It

was further posited that to restrict the application to the AO would result in strict liability

which is an extreme legal concept which assigns guilt in the absence of blame or fault.

In terms of existing financial laws, the AO is legally obliged to take steps to prevent losses

and if losses occur, to determine the source of the loss, whether anyone can be held

responsible in law and if so to recover the loss from that person. Where losses are

irrecoverable or no official can be held liable in law they may be written off.

4

The PFMA and MFMA provide specific steps to be taken by the AO when a loss occurs.

These include the manner in which the loss must be accounted for in the financial reporting

process, the human resource actions to be taken, the reporting of criminal offences and debt

recovery. The role of the AG in terms of the amendment Bill is in essence a compliance

management one coupled with enforcement where an AO has renegaded on his or her

responsibilities. The aspect of blameworthiness is thus not in relation to the cause of the loss

but rather the failure to recover that loss in terms of existing legal obligations. An AO who

acts in good faith and complies with the legislated legal prescripts relating to losses will

never find him or herself in the position of being held personally liable. Therefore in our view

there is no strict liability, on the contrary the AO must be shown to have failed to take

adequate steps.

The AG’s role, simply put, is to ensure that an AO does what the law requires of that AO. No

new duties or obligations are created in terms of this amendment Bill. The argument that it

will be difficult to recruit Municipal Managers in particular if the Bill becomes law is therefore

weak. The job responsibilities of an AO is one that is crafted in law and any AO who accepts

such a job must accept the legal duties and obligations attached to the post. Notwithstanding

same, nothing prevents AO’s from procuring professional indemnity insurance.

5. Definition of “undesirable audit outcome”

Many submitters raised concerns that the definition was problematic as it was not a known

technical term, which may lead to interpretation problems. The AG is in agreement and has

proposed a new definition.

We have considered the proposed definition and agree, that subject to regulations

prescribing the test for materiality, the new definition is more legally sound. However, the

definition caters for actions in addition to those that cause financial loss and also speaks to

possible risks. Therefore, when using the definition in the context of the recovery of losses

we will apply our mind in ensuring that the term speaks only to a material irregularity that has

already occurred and which may have resulted in a financial loss.

6. Discretionary Audits

The Constitution provides for two specific categories of audits- mandatory and discretionary.

The PAA reflects these provisions but in addition also provides that audits of the national

and provincial legislatures, constitutional institutions and municipal entities will be

mandatory.

5

Dr R Naidoo suggested that the audits of all public entities should be mandatory. Her

argument, as we understood it, was that those entities would have to be audited in any case

by external auditors at a fee. The AG is also responsible in these cases for agreeing to the

appointment of the external auditor as per section 25 of the PAA. Therefore, if this fee was

paid to the AG there would be no adverse cost or resource implications.

The AG does not support the recommendation due to the fact that “the economics of the

office would not sustain such an obligation”. The AG further stated that, “the mandatory

auditing of public entities will require an amendment to section 188(1) of the Constitution” as

it is creating an additional category for mandatory audits. We respectfully disagree with this

view and do not believe that a constitutional amendment would be necessary to provide for

the mandatory auditing of all public entities. Section 188 (1) (c) already provides that it will

be mandatory to audit “any other institution or accounting entity required by national or

provincial legislation to be audited by the Auditor-General.” There is no reason in law why all

public institutions cannot be subjected to audits by the AG. This is a policy rather than a

legal decision. A simple amendment of the Public Audit Act to list these entities as mandatory

will suffice. To argue otherwise would mean that the listing of legislatures, municipal entities

and constitutional institutions in the category of mandatory audits in the Public Audit Act is

also unconstitutional.

In the AG’s response to Dr Ramola’s submission it also stated that the purpose of the

proposed amendment of section 4(3) and (4) of the PAA was to give the AG “a wider

discretion to opt out of small, mandatory audits such as boards, trusts and museums.” In

considering the proposed amendment initially, we understood it to be providing a basis,

through prescribed criteria, for the AG to opt out of certain discretionary audits despite being

requested by the Auditee to conduct that audit. It is clear however from the submission that

the intention went further to allow for a legal basis to opt of out of mandatory audits. We are

of the view that this would be unconstitutional and can only be achieved by amending the

Constitution to provide the AG with the right to opt out of audits where national or provincial

legislation provided that the audit is mandatory and therefore must be conducted by the AG.

Notwithstanding the above, we have taken cognisance of the AG’s dilemma- namely that

Parliament simply passes or has passed legislation requiring the AG to audit the institution

established in terms thereof without regard to capacity, budgetary and other constraints of

the AG. In respect of new legislation and in the absence of a constitutional amendment to

section 188 (1)(c) we propose that a new amendment be crafted that provides for a

6

consultation process between the legislature and the AG when processing future Bills that

contain a mandatory obligation on the AG.

In terms of existing legislation requiring mandatory audits we propose that the AG lobbies

Parliament to pass a general laws amendment bill to amend all identified legislation to effect

an amendment stipulating that the audit is no longer mandatory but rather discretionary and

such discretion will be exercised in accordance with applicable criteria.

7. International Audits

Based on our view of the meaning and extent of section 188 (4) of Constitution, we are of

the opinion that it would not be unconstitutional to permit the AG to conduct international

audits provided that the services rendered in respect thereof do not detract from the primary

obligations of the AG.

We are not convinced that an international audit does not support or strengthen democracy.

Whilst the correlation may not be direct it appears that these audits carry with it staff

development benefits in terms of skills and exposure as well as opportunities for the AG to

gain knowledge and experience in new auditing systems and emerging international best

practices. These benefits may serve to enhance the quality of local audits as well as

establish the AG as a reputable audit institution.

8. Recovery process

As indicated previously various objections to the proposed recovery process were cited.

Whilst we do not believe that the issuing of a certificate and recovery of debt from an AO in

and of itself is unconstitutional, it is crucial that the procedure followed by the AG in fulfilling

such a function does not invite constitutional or legal challenges. The process must be

designed in such a manner so as to not impede or encroach on the legal rights and

obligations of Accounting Officers and Accounting Authorities or the independence of other

spheres of government.

Accordingly, we partly support the proposed 3-tier process presented by the AG. 6We do

however have certain legal concerns and will address these in respect of each tier:-

Level One- Issuing of Audit Report with Recommendation(s)

6 See Annexure A for diagram representation

7

We are in agreement with the proposed process for level one provided that it is clear that the

audit finding is independent of the recommendation and the former is binding unless

challenged on review in court. In this regard we are of the view that reference should be

made to the management letter as this step constitutes an “audi alteram partem” before a

binding finding. We also propose that the terms “binding” and “non-binding” are not used as

this may lead to unintended challenges on the validity of audit reports.

Level Two- Issuing Remedial Action

We support level two-namely the issuing of specific remedial action relating to the finding

and recommendations as per the audit report. We are of the view that the 6 months lapse

between level one and two may be too long in certain circumstances but appreciate the AG’s

stance that this period is necessary to allow the AO time and space to comply.

However, we bring to the attention of the committee that the issuing of a certificate is linked

specifically to the recovery of financial losses. As per the proposed definition of “material

irregularity”, it is clear that the AG does not only report on UIFW expenditure but also non-

compliance with legislation and breach of fiduciary duty that may not have resulted in a loss.

As such, a recommendation or later remedial action directing the AO to do something, other

than recover a loss, cannot be followed up with a certificate of debt. We therefore

recommend that the issuing of a certificate be one measure and additional thought be given

as to how compliance and action can be ensured in respect of other issues.

Level Three- Referral for investigation and issuing of certificate

We do not support the level three proposal. According to the AG at this stage (6 months after

the issuing of remedial action and 12 months after the audit report), if no steps or inadequate

steps have been taken to recover losses the AG will refer the matter for investigation. Only

once the outcome of the investigation is known will the AG proceed to issue a certificate. We

are already concerned about the additional time frame of 6 months between level two and

three. However, level three is particularly problematic as the time frame is now left open and

a dependency is created on an investigative body.

This dependency waters down the effect of the remedial binding action because the non-

action is not dealt with but rather the matter is sent for further investigation, the outcome of

which is unknown. In the Nkandla judgment the Court stated as follows- “If compliance with

remedial action taken were optional, then very few culprits, if any at all, would allow it to

have any effect. And if it were, by design, never to have a binding effect, then it is

8

incomprehensible just how the Public Protector could ever be effective in what she does and

be able to contribute to the strengthening of our constitutional democracy.”

The referral to an investigative body as a step in determining whether to issue a certificate is

problematic for a number of other reasons. In law none of the intended “appropriate bodies”

are under any legal obligation to report to the AG and to create such an obligation would

possibly require the amendment of the various pieces of legislation that govern these bodies.

Furthermore, in most cases where the matter is of a criminal nature it will ultimately,

following an investigation, be referred to the National Director of Public Prosecutions to

institute charges. As part of a criminal case a competent court can order that

misappropriated funds are paid back.

In our view the referral should not be linked to the issuing of a certificate but should rather be

a stand-alone provision empowering the AG, at any stage of the auditing process, to refer a

matter for investigation. This is based on the premise that the audit finding stands and has

legal force and effect if an AO fails to follow up on that finding in terms of the AG’s

recommendations. Not every UIFW transaction is necessarily criminal. To create a

dependency on another investigative body provides an AO with the opportunity to simply

ignore the AG’s recommendations in terms of improving processes and taking disciplinary

action as the AO may enjoy a level of comfort that the investigation will not uncover

something criminal and therefore he or she will not attract any liability anyway.

Our proposal is that at the stage of level 3 the AG must, with regard to certain

considerations, determine whether he intends to issue a certificate or not. These factors may

include-

The outcome or progress report of a forensic investigation conducted by the AG in

terms of section 29 of the PAA;

The outcome or progress report in respect of a referral; and

The report of the AO in terms of steps taken to follow up on a loss and the

recommendations in the remedial action report.

In this way the AG can act in the absence of a report, if he so wishes, based purely on the

fact that despite his audit finding reflecting a loss nothing has been done to determine the

cause of the loss and to hold anyone responsible in law.

9. Issuing of certificate- audi/appeal

9

A concern was raised that there is no internal appeal mechanism built into the Bill to

challenge the issuing of a certificate by the AG and the court review process, which is the

only appeal option, is costly.

We have carefully considered the matter and we are of the view that to allow another

structure, whether internal to the AG’s office or external, with the power to overturn a

decision of the AG would be unconstitutional as it would affect the independence of the AG

to perform his functions.

However, we are open to exploring the option of a two-tiered audi-alteram-partem process

rather than an appeal process. This may work as follows-

Step1- AG issues a notice of intent to issue a certificate to an AO and provides the AO with a

prescribed period in which to make written representations.

Step 2- If in considering the written representations, the AG’s intent has not changed he can

invite the AO to make oral representations to an advisory committee established in terms of

section 5(2)(b) of the PAA.

Step 3- If after considering the views of the special advisory committee the AG is still of the

view that there is sufficient cause to issue a certificate the AG will proceed.

10. Debt recovery

A multitude of submissions raised concerns about the adverse impact that a debt recovery

process will have on the resources of the AG. There is general agreement that the function

should not be given to the AG. The question for determination therefore is, if not the AG then

who?

A proposal was received that the AG should make use of pro-bono services of private

attorneys to conduct the collection on its behalf.

Firstly, it is necessary to understand the concept of pro bono. The term comes from the latin

word “pro bono publico” meaning for the public good. It describes legal work undertaken

without payment for clients who would otherwise be unable to access legal services. Section

34 of the Constitution provides that every person has the right to have a dispute resolved by

the application of law decided in a fair public hearing before a court. However, the reality is

10

that for the majority of South Africans legal services are out of reach. Thus to give effect to

the Constitution and the pro bono principle the law society rules governing the legal

profession provides that private attorneys must commit to a certain number of pro-bono

hours.

Whilst the collection of money owing to the state is certainly for the public good it must be

balanced against the rights of the indigent to legal representation. It is hard to rationalise

why the state should be provided with the benefit of pro-bono services especially in the

context of recovering losses due to criminal conduct or mismanagement.

Practically this arrangement will also be very difficult to manage as the AG will serve as the

instructing client and will be expected to manage the relationship with the private attorney.

The AG may possibly be faced with the problem of attorneys failing to do their part with the

result that the AG has to resort against legal action against the attorney to ensure

compliance.

Lastly, this arrangement will require an amendment to the Legal Practice Act which at this

stage would be impractical.

The second option was to refer the duty of recovery to the National or Provincial Treasury.

This option appears to be a natural extension of the Treasury oversight role in respect of

fiscal management. However, there are stumbling blocks. This new responsibility has not

been costed and it is not clear to what extent it will require additional capacity and resources.

Furthermore, some auditees (like municipalities) partly generate their own revenue which will

require an additional step after recovery- the transfer of recovered funds back to the relevant

entity. Section 64 (1) (d) of the MFMA states that all funds received by a municipality must

be deposited into the bank account of the municipality.

The third and preferred option is for the executive authority to collect the debt in terms of an

entities own debt recovery policy. In the case of national and provincial departments and

public entities this will be the relevant line Minister or the MEC as the case may be. For

municipalities it will be the Municipal Council. Monies recovered by national and provincial

departments will need to thereafter be transferred into the relevant revenue fund as per the

requirements of section 13 of the PFMA.

11

The Kader Asmal report on Chapter 9 Institutions notes that “the practical implementation of

any recommendations emanating from an audit is best achieved with the active participation

of the Executive”.7

This option gives effect to this sentiment and also has practical benefits. Debt collection

capacity already resides within institutions and the Executive Authority can simply rely on the

existing mechanisms. Furthermore, the cost associated with the recovery is borne by the

institution which suffered the loss rather than another organ of state being saddled with the

problem. Furthermore, it ensures that the AG does not encroach on the debt collection

prescripts applicable to a particular entity thus minimising legal risks.

Lastly, this option lends itself to more effective oversight by Parliament and Provincial

Legislatures who can call the relevant Minister or MEC to account.

11. Audit fees

Section 23 (6) of the Public Audit Act currently provides that if the audit fee exceeds one

percent of the total current and capital expenditure of the auditee, and in the opinion of

National Treasury the auditee has financial difficulty to settle the fees then the National

Treasury must defray the cost in excess of the one percent. This obligation is not applicable

to national and provincial departments.

A practical example of the manner in which the payment will be calculated is as follows:

A municipality incurs an audit fee of R120 000. Its total current and capital expenditure is

R10 000 000 with the result that the audit fee is in excess of 1% of its expenditure. If NT is of

the view that the municipality has financial difficulty, it would defray the additional cost of

R20 000 to satisfy the account of the AG.

National Treasury proposed that the provision be redrafted to reflect that National Treasury

would only pay such excess amount or percentage as it and the AG agree annually. In the

example above it would mean, in the absence of such agreement, National Treasury will pay

nothing. If there is agreement and the agreement is not in respect of 100% of the R20 000 it

would mean that the AG would have to attempt to recover the balance from the auditee and

7 Report of the ad hoc Committee on the Review of Chapter 9 and Associated Institutions-A report to the National Assembly of the Parliament of South Africa -31 July 2007- see page 67.

12

likely follow legal debt recovery procedures to achieve same or alternatively will have to

write-off the debt.

Whilst we appreciate the difficulty that National Treasury faces in the current challenging

fiscal climate which favours an austerity approach we are presented with a legal dilemma.

The AG is constitutionally mandated to conduct certain mandatory audits.

There is no election or discretion based on the ability or non-ability of the auditee to settle

the audit fees. As such the AG, in the absence of National Treasury support, has no choice

but to conduct audits even where it has no reasonable prospect of securing payment of the

audit fee.

This leads to a situation where the resources of the AG will be stretched, the quality of audits

may be compromised and the AG may, in pursuing payment of fees, be detracted from its

core business by having to focus on debt recovery.

There is no legal barrier preventing the AG from requesting an appropriation from Parliament

and indeed section 36 (1) (b) specifically provides for an appropriation as a source of funds.

The question of how excess fees must be paid and by whom is a policy issue that must be

considered in light of the AG’s legal obligation to audit. If a role for National Treasury is

retained the clause must be clear and provide for consequences where an agreement

cannot be reached. In its current form it is merely an “agreement to agree” which in our law

is non-enforceable in the absence of a clear mechanism to secure agreement. 8

12. SA GAAP /GRAP reporting framework

Comments were received challenging the fact that the AG is non-compliant with the PFMA in

so far as it does not apply the Generally Recognised Accounting Practice issued by the

Accounting Standards Board in its own financial reporting.

The assertion that the AG is legally non-compliant based on its use of a different framework

is without merit. The AG, unlike other chapter 9 Institutions, is not subject to the PFMA and

is not listed as a constitutional institution in terms of Schedule 1 thereto.

8 See Southernport Developments (Pty) Ltd v Transnet Limited [2004] JOL 13030 (SCA).

13

Section 41 (2) of the PAA currently provides that the financial statements of the AG must be

in accordance with South African Statements of Generally Accepted Accoutring Practice (“

SA GAAP”) or other international best practice approved by the oversight mechanism. SA

Gaap has however been withdrawn for financial years commencing December 2012 and this

necessitates an amendment to the PAA for the sake of correctness.

The issue of which financial reporting framework the AG should utilise is a policy issue. We

are however comfortable that the approval mechanism contained in section 41(2), which

requires the Oversight Mechanism to approve, the standard used is sufficient to prevent any

risk of the AG utilising a reporting framework that is not reliable or accurate.

In this regard, we urge the Committee, when considering section 41(2) permission to apply

its mind to auditing practice statements issued by professional bodies such as the

Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors in reaching its decision on the acceptability of a

particular framework. 9

The Committee is nonetheless requested to consider whether section 41(2) should be

amended to replace SA GAAP with GRAP, whether to simply delete the option of SA GAAP

or alternatively to delete the option of using other international best practice. The latter

option is however problematic as, according to the AG, GRAP in its current form is not

suitable for the nature of services undertaken by the AG.

13. Regulations

Accountability now raised a concern that the Bill empowered the AG to make regulations

relating to recovery and suggested that this would result in conflict of interest.

There is no basis in law that prevents the AG from making regulations. It is extremely

common that the passing of regulations, which is a form of sub-ordinate legislation, is

delegated to an executive authority or other suitable body. In the case of the AG there is no

executive authority that oversees the powers and functions of the AG and the AG him or

herself is considered to be the subject matter expert. Subordinate legislative bodies who

9 By way of example see “South Agfrican Auditing Practice Statement-Financial Reporting Frameworks an dthe Auditor’s Report, revised November 2013”, available at https://www.irba.co.za/upload/SAAPS%202%20-%20Reporting%20Frameworks.pdf.

14

issue regulations do not have original legislative competence and must act within the

confines of the enabling legislation, in this case the PAA as well as the Constitution as

supreme law. In the Constitutional Court case of New Clicks, Chaskalson J stated that the

making of delegated legislation by a member of the executive is an essential part of public

administration, in that it gives effect to legislative policies.10

Further, it provides the detailed infrastructure necessary to give effect to a law. As such we

are satisfied that there are sufficient checks and balances on the AG’s power to issue

regulations, including the requirement for consultation with the Oversight Mechanism prior to

issuing any regulations.

The Committee can however consider whether it would want to build in additional

safeguards such as a compulsory public participation process in the form of a duty on the

AG to publish draft regulations for comment prior to issuing same.

14. Technical drafting issues:

After consideration of the submissions, we note that there are a number of technical drafting

changes that must be made. These are summarised below:

a) Delete references to repealed legislation

A submission received from Dr Naidoo pointed out that the Public Audit Act, 2005, refers to

legislation that has been repealed.

In this regard, it was pointed out that the Public Audit Act refers to the Public Accountants

and Auditors Act, 1991 (Act No. 80 of 1991), which has been repealed and replaced by the

Auditing Professions Act, 2005 (Act No. 26 of 2005). The Auditing Professions Act came into

operation on 1 April 2006 and in terms of section 58(1), read with Schedule 1, repeals the

whole of the Public Accountants’ and Auditors’ Act, 80 of 1991.

Therefore, all references to the Public Accountants and Auditors Act, in the Public Audit Act

must be deleted and replaced with the Auditing Professions Act. So these amendments will

need to be made in the draft Bill.

10 New Clicks South Africa (Pty) Ltd v Tshabalala-Msimang and Another NNO; Pharmaceutical Society of South Africa and Others v Tshabalala-Msimang and Another NNO 2005 (2) SA 530 (C)

15

b) Commencement date of Public Audit Amendment Act, 2018

Clause 11 of the draft Bill provides that the Public Amendment Act, 2018 (this draft Bill once

passed and signed by the President) will come into operation on 1 April 2019.

However, clause 4 of the draft Bill, which amends section 7(1A) of the Public Audit Act will

not be able to be put into operation until the Determination of Remuneration of Office

Bearers of Independent Constitutional Institutions Laws Amendment Act 22 of 2014 is

brought into operation.

This therefore impacts on the commencement of this clause- which will be dependent on the

coming into operation of the Determination of Remuneration of Office Bearers of

Independent Constitutional Institutions Laws Amendment Act 22 of 2014 OR 1 April 2019 –

whichever date is the later. The reason it would have to be the later date is because that

clause cannot be brought in before this draft Bill is in operation and neither can that clause

be brought in if the Determination of Remuneration of Office Bearers of Independent

Constitutional Institutions Laws Amendment Act 22 of 2014 is not yet put into operation.

c) Ensure that words defined in the Bill carry their correct meaning throughout the principal

Act

The Bill introduces the word “prescribed” to mean prescribed by way of regulation made

under section 52 of the Act – to avoid having to keep saying that the AG must make

regulations.

However, there is a section in the Act (section 12(3)(b)) where the word “prescribing” is used

but is not intended to be by way of regulation but rather just means to “set out”. Hence, this

word “prescribing” would need to be replaced so that it is not interpreted to mean by way of

regulation.

15. Way Forward

In order to finalise the drafting of the Bill the Committee must conclude on the following:-

16

a. Whether former AO’s are to be included to the extent that they failed to act during the

recovery process? In other words an AO that resigns after the 6 month period following

the issuing of remedial action will still be liable for payment.

b. Whether the issue of mandatory audits in future legislation be managed by inserting a

provision in the Bill requiring consultation with the AG? This consultation may be

between SCOAG or the relevant line committee processing the bill and the AG.

c. Whether the recovery process proposed by the AG be adopted in the proposed form or

whether level 3 be recrafted so as not to create a dependency between the outcome of

an investigation and the issuing of a certificate?

d. Whether the term “appropriate bodies” in relation to the referral function must be listed

specifically? If so who would these bodies be?

e. Whether the debt collection function be transferred to the National Treasury or

alternatively to the relevant Executive Authority?

f. Whether the audi-alteram-partum process be redesigned to include an additional level of

consultation at the level of a committee established for this purpose?

g. Whether the provisions on audit fees must be amended and if so how?

17

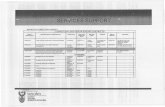

ANNEXURE A- AG’S PROPOSED PROCEDURE FOR RECOVERY

Step 1March 2016

End of financial year

Step 2April –June 2017

Audit period Management letter, identifying UIFW is issued and engagements take place in respect thereof

Step 3July 2018

Audit report issued with recommendations in respect of UIFW(non-binding)

Step 4Jan 2018

AG follows up audit recommendations. No/insufficient progress= remedial action

Step 5May 2018

Final Follow up by AG.No/insufficient progress= referral to investigative body

Step 6 Date Unknown

Receive report back from investigative body. Follow process to issue certificate based thereon or close file

18

![[XLS]pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.compmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/RNW3184... · Web view106879933.52 0 48116477.539999999 0 50048759.009999998 0 72170623.049999997](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5af7ae927f8b9a190c917535/xlspmg-assetss3-website-eu-west-1-view10687993352-0-48116477539999999-0-50048759009999998.jpg)