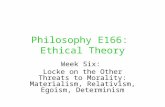

Philosophy E166: Ethical Theory

description

Transcript of Philosophy E166: Ethical Theory

Philosophy E166: Ethical Theory

Week Five: Locke on Religion and Morality

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

Materialism, naturalism

Atheism

Psychological egoism

Relativism

Determinism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Materialism, naturalism

Atheism

Psychological egoism

Relativism

Determinism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Atheism

Psychological egoism

Relativism

Determinism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Psychological egoism

Relativism

Determinism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Relativism

Determinism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Relativism Moral objectivity

Determinism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Relativism Moral objectivity

Determinism Libertarianism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Relativism Moral objectivity

Determinism Libertarianism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Unorthodox Christianity

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Relativism Moral objectivity

Determinism Libertarianism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Unorthodox Christianity

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Secularism moralism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Relativism Moral objectivity

Determinism Libertarianism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Unorthodox Christianity

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Secularism moralism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Compatibility of egoism and morality

Relativism Moral objectivity

Determinism Libertarianism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Unorthodox Christianity

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Secularism moralism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Compatibility of egoism and morality

Relativism Moral objectivity Distinction between divine justice & human justice, natural law & civil law

Determinism Libertarianism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Unorthodox Christianity

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Secularism moralism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Compatibility of egoism and morality

Relativism Moral objectivity Distinction between divine justice & human justice, natural law & civil law

Determinism Libertarianism Metaphysical compatibilism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

PositionLocke’s Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Unorthodox Christianity

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Secularism moralism

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Compatibility of egoism and morality

Relativism Moral objectivity Distinction between divine justice & human justice, natural law & civil law

Determinism Libertarianism Metaphysical compatibilism

Perceived Hobbesian Threat

to Ethics

The Christian

Response

Hobbes’s True

PositionLocke’s Position

Materialism, naturalism

Dualism, supernaturalism

Unorthodox Christianity

??

Atheism Voluntarism or intellectualism

Secularism moralism

??

Psychological egoism

Existence of morality and altruism, with God’s help

Compatibility of egoism and morality

Relativism Moral objectivity Distinction between divine justice & human justice, natural law & civil law

Determinism Libertarianism Metaphysical compatibilism

Locke and the Threat of Atheism

• When we think of Locke today, we do so because of the continuing relevance – of his political views (liberal, libertarian) to

our secular society– of his empiricism to our secular conception

of knowledge and reality

Secular Influence of Essay

• The conception of knowledge that Locke develops in the Essay is tied to a secular conception of knowledge

• It isn’t an account of how knowledge is based on authority or scripture, but of how it’s tied to observation and science

• So it is an important contribution to thinking about how knowledge is possible in a secular society

• Most of the thinking about Locke today is done in secular terms

Secular Influence and Locke’s Religion

• Overlooks how deeply religious most of his writing is

• The secular influence of Locke conceals the degree his works – were inspired by religious questions and – are devout in the positions they took on religious

questions

From the Essay’s Epistle to the Reader

• One indication in his “epistle to the reader” at the start of Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke’s work on the nature of knowledge– We do not ordinarily recall it as concerning religion or morality

• Locke wrote that the book originated with a discussion we can date to 1671:– “Were it fit to trouble thee with the history of this

Essay, I should tell thee, that five or six friends meeting at my chamber, and discoursing on a subject very remote from this, found themselves quickly at a stand, by the difficulties that rose on every side.”

Locke “chamber” in 1671

• Locke was living in Exeter, the London residence of Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury

• Locke had met Shaftesbury in 1666 when Shaftesbury had come to Oxford to be treated for a liver problem

• Locke had been trained as a physician• Locke became his personal physician, and he even moved in

with Shaftesbury• Before long, Locke became Secretary to the Lords and

Proprietors of the Carolinas, Shaftesbury’s group that administered the Carolina colony

Among “five or six friends meeting” at his chamber was James Tyrrell

• We know that among those Locke calls the “five or six friends meeting at my chamber” was James Tyrrell

• Tyrrell’s Patriarcha non Monarcha (or The patriarch Unmonarched) was a reply to Robert Filmer’s defense of royalism in Patriarcha

• Tyrrell’s book has been thought by many to have been the model for Locke’s own attack on Filmer in his First Treatise of Government– Also a source for many of Locke’s ideas in the Two Treatises as a whole

• We know that Tyrrell was there because of an annotation Tyrrell made in his personal copy of the Essay

• Tyrrell noted that the subject of the meeting was “the principles of morality and revealed religion”

The Origin of the Essay

• Locke continues:– “After we had awhile puzzled ourselves, without coming

any nearer a resolution of those doubts which perplexed us, it came into my thoughts that we took a wrong course; and that before we set ourselves upon inquiries of that nature, it was necessary to examine our own abilities, and see what objects our understandings were, or were not, fitted to deal with. This I proposed to the company, who all readily assented; and thereupon it was agreed that this should be our first inquiry….”

“hasty and undigested thoughts”

• “Some hasty and undigested thoughts, on a subject I had never before considered, which I set down against our next meeting, gave the first entrance into this Discourse; which having been thus begun by chance, was continued by intreaty; written by incoherent parcels; and after long intervals of neglect, resumed again, as my humour or occasions permitted….”

• What exactly Locke and his friends had been discussing – what exact “principles of morality and revealed religion” and what the “wrong course” had been – are uncertain

• As are the “hasty and undigested thoughts, on a subject [he] had never before considered”

Religious Controversy on Locke’s Mind

• We know that religious matters were on Locke’s mind during this period

• Four years before, in 1667, Locke had written the unpublished Essay Concerning Toleration – responded to the ongoing opposition to the Church

of England from Nonconformists, and the new policy of intolerance adopted by the Church

– Church’s policy included penalties for those who failed to attend and larger penalties who worshipped elsewhere

Intolerance After Restoration

• The Church of England was a state church• Under Cromwell, there had been toleration, at least

toward non-Catholics• Charles II was restored in 1660• After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, this

toleration ended• The Uniformity Act of 1662 ordered that

– all ministers be ordained in the state church– all religious ceremonies follow the Book of Common Prayer– only adherents could hold public office

Locke’s Response to Uniformity Act: Worship a “Private Matter”

• At the time of the Uniformity Act, Locke had responded in his Second Tract on Government

• Argued that worship was a private relationship between a person and God, not a public one

• On this premise he argued against religious freedom• Argued that the state could regulate the public

aspects of religion without interfering with worship• Locke apparently saw this as necessary to

maintaining public order in the aftermath of the English Civil War

Reverses Himself in An Essay Concerning Toleration (1667)

• Locke reversed himself five years later in the Essay Concerning Toleration (1667)

• Argued that worship had a public aspect that was not the concern of the state:– “Religious worship being that homage which I pay to that God I

adore in a way I judge acceptable to him, and so being an action or commerce passing only between God and myself, hath in its own nature no reference at all to my governor or to my neighbour, and so necessarily produces no action which disturbs the community. For kneeling or sitting at the sacrament can in itself tend no more to the disturbance of the government, or injury of my neighbour, than sitting or standing at my own table.... “

The State Has No Role Enforcing Religious Practices

• He argued that the state has no role in enforcing religious practices:– “Can it be reasonable

• that he that cannot compel me to buy a house should force me [in] his way to venture the purchase of heaven,

• that he [who] cannot in justice prescribe me rules of preserving my health should enjoin me methods of saving my soul,

• he that cannot choose a wife for me should choose a religion?...”

The Only Force Appropriate

• The only force appropriate:• “But if God (which is the point in question) would have

men forced to heaven, it must not be by the outward violence of the magistrate on men’s bodies, but the inward constraints of his own spirit on their minds, which are not to be wrought on by any human compulsion, the way to salvation not being any forced exterior performance, but the voluntary and secret choice of the mind….”

Toleration Extended to Morality

• He recognized that there was a close connection between religion and morality

• Religions prescribe moral rules for their followers• Whether or not one follows those moral rules is seen

as determining if one goes to heaven:– “actions, which are thought good or bad in themselves, …

are the vigorous active part of religion, and that wherein men’s consciences are very much concerned.”

• Nevertheless, he extended toleration even to such actions

Extending Toleration to Moral Actions

• “Yet give me leave to say, however strange it may seem, that the lawmaker hath nothing to do with moral virtues and vices, nor ought to enjoin the duties of the second table [of the Ten Commandments] any otherwise, than barely as they are subservient to the good and preservation of mankind under government. For could public societies well subsist, or men enjoy peace or safety, without the enforcing of those duties, by the injunctions and penalties of laws, it is certain the lawmaker ought not to prescribe any rules about them, but leave the practice of them entirely to the discretion and consciences of his people…..”

Morality a Matter Between God and Souls

• “[T]hey would then become only the private and super-political concernment between God and a man’s soul, wherein the magistrate’s authority is not to interpose. God hath appointed the magistrate his vicegerent [delegate] in this world, with power to command; but ’tis but like other deputies, to command only in the affairs of that place where he is vicegerent…. The magistrate hath nothing to do with the good of men’s souls or their concernments in another life but is ordained and entrusted with his power only for the quiet and comfortable living of men in society one with another…”

But Locke Not a Secularist

• We have been viewing Hobbes as a secularist • I used the term “secularism” to refer to the

view that atheism and morality are compatible• It might seem from these passages that Locke

was, like Hobbes, what I called “a secularist” • But it would be a mistake to label Locke a

“secularist” in this sense • It was Locke’s view that toleration had it limits

No Toleration for Catholics

• “As to the papists,” Locke wrote, “ ’tis certain that several of their dangerous opinions which are absolutely destructive to all governments but the pope’s ought not to be tolerated….”

No Toleration for the Intolerant

• “ For it is unreasonable that any should have a free liberty of their religion, who do not acknowledge it as a principle of theirs that nobody ought to persecute or molest another because he dissents from him in religion.”

No Toleration for Atheists

• Even though “purely speculative opinions” he argued, should always be tolerated, atheists could not fall back on this principle for protection:– “I must only remark before I leave this head of

speculative opinions that the belief of a deity is not to be reckoned amongst purely speculative opinions, for it being the foundation of all morality, and that which influences the whole life and actions of men, without which a man is to be counted no other than one of the most dangerous sorts of wild beasts, and so incapable of all society.”

The Carolina Constitution

• Two years later in 1669, as secretary for the Carolina group, Locke participated in the drafting of the constitution for the Carolinas

• The constitution had the same religious toleration that Locke had argued for in the Essay Concerning Toleration

• But it had the same intolerance for atheists

No Controversy Because Unpublished

• One reason Locke never generated the hostility that Hobbes did was Locke didn’t publish An Essay Concerning Toleration

• He also tended to withhold from publication other works of his that contained controversial views

• These unpublished works ended up passing into Tyrrell’s hands at Locke’s death

What Is Said about Atheists in A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689)

• Locke elaborated on intolerance to atheists 18 years later in A Letter Concerning Toleration:– “Those are not at all to be tolerated who deny the

Being of a God. Promises, Covenants, and Oaths, which are the Bonds of Humane Society, can have no hold upon an Atheist. The taking away of God, though but even in thought, dissolves all. Besides also, those that by their Atheism undermine and destroy all Religion, can have no pretence of Religion whereupon to challenge the Privilege of a Toleration.”

Protecting Society from Atheists’ Immorality, Not Changing Them

• The problem on Locke’s view was not just that the atheist could not swear an oath – since the atheist would have nothing to swear on

• The problem was that atheists do not follow moral rules at all

• Locke assumes anti-secularism• This was one of the practical aspects of Locke’s response

to the threat to ethics• Intolerance was not intended to change the minds of

atheists but merely to protect society from their potentially immoral ways

The Fundamental Law of Nature: the Foundation of Morality

• These issues of toleration are practical aspects of Locke’s anti-secularism

• A more theoretical aspect of Locke’s response is given at the start of the Second Treatise

• The account that Locke gives of the foundations of moral value

• For Locke at the foundation is what Locke in §16 of the Second Treatise calls “the fundamental law of nature” – (He uses the phrase in §§134, 135, 159 and 183 as well)

The Basic Statement of the Fundamental Law of Nature

• He sets out this “fundamental law” in §6: – “The state of nature has a law of nature to govern

it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions….”

The Fundamental Law of Nature (cont.)

• Locke’s counterpart to Hobbes’s Fundamental Law:– “…. Every one, as he is bound to preserve himself,

and not to quit his station willfully, so by the like reason, when his own preservation comes not in competition, ought he, as much as he can, to preserve the rest of mankind, and may not, unless it be to do justice on an offender, take away, or impair the life, or what tends to the preservation of the life, the liberty, health, limb, or goods of another.”

What Is the Foundation of Locke’s Fundamental Law of Nature?

• In his first chapter on Locke, Rawls discusses the “role and content” of the fundamental law

• My interest right now is different • I am interested in its foundation

Reason Is Not Itself the Foundation

• Locke says in §6 that “reason … is that law” • He says that reason teaches all people who will

consult it• But I take it that he should have said not that

reason is the law • He should have said that reason has the law as its

object• If that’s right, then the question is:

– How does reason arrive at the law?

An Illusion of Innateness, or of Intellectual Intuitions

• In §11 the suggestion might seem to be that, in the case of our understanding of the rights of punishment, it works by innateness:– “And Cain was so fully convinced, that everyone

had a right to destroy such a criminal, that after the murder of his brother, he cries out, Every one that findeth me, shall slay me; so plain was it writ in the hearts of all mankind.”

Is Locke Suggesting an Innate Basis to Moral Knowledge?

• It might be natural to interpret these last words – “so plain was it writ in the hearts of all mankind” – as indicating a conception of reason like that of Plato and Descartes

• According to this conception, through reason we have “intellectual intuitions” of truth

• And in particular of moral truth• Recall the story in Plato’s Meno• That we can discover the nature of virtue through recollection

– we were born knowing it • It is merely a matter of bringing what we know to mind

Locke Rejects Innate Ideas

• Except that as an empiricist Locke does not seem to be able to write that way.

• There are on Locke’s story certainly no innate ideas of morality

• There are no innate ideas at all, according to what Locke writes in Book One of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding

• Suppose “the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters….” (Essay, Bk. II, Chap. I, §2.) See arguments in Bk. I, Chap. III.

Locke Takes Morality to Be Math-Like

• He says in Books Three (Chap. 11, §16) and Four (Chap, 3, §§18-20) of the Essay that moral conclusions can be demonstrated in the way that mathematical conclusions can be

• This looks a bit like Hobbes, who says the same thing about his own “laws of nature”

• It is natural to interpret the quasi-mathematical reasoning Hobbes has in mind as game-theoretic, like that connected with the prisoner’s dilemma

• This is the work of “reason” for Hobbes • What about Locke?

Two Math-Like Approaches

• Perhaps we have game-theoretic reasoning in §11, the section on punishment in the state of nature.

• But another way to take mathematics as a model is to think about the relationships between axioms and postulates, on the one hand, and theorems and colloraries, on the other.

• Let me suggest thinking of it this way.

The Foundation for Locke of Our Reasoning about Morality

• Turn back to §6, the section above in which Locke introduces “the fundamental law of nature” and its content

• Here there are several fundamental ideas underlying what he says, some even more fundamental than the fundamental law.

• In §4 of Locke I, Rawls argues that “the freedom and the equality” in the state of nature are fundamental to it

• But if you look carefully at what Locke and Rawls both say, you will find something even more fundamental –

• God’s role as underwriter of the freedom and the equality

What Reason Says

• “… reason … teaches all mankind … that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions: for men being all the workmanship of one omnipotent, and infinitely wise maker; all the servants of one sovereign master, sent into the world by his order, and about his business; they are his property, whose workmanship they are, made to last during his, not one another's pleasure…”

What More Reason Says

• “ … and being furnished with like faculties, sharing all in one community of nature, there cannot be supposed any such subordination among us, that may authorize us to destroy one another, as if we were made for one another's uses, as the inferior ranks of creatures are for ours.”

God’s Workmanship as Foundation

• Again, Locke writes that “men being all the workmanship of one omnipotent, and infinitely wise maker; all the servants of one sovereign master, sent into the world by his order, and about his business; they are his property, whose workmanship they are, made to last during his, not one another's pleasure.”

• This creationist idea of “workmanship” – that God is the “workman” and we are the products – seems to be the fundamental idea here.

Hobbes vs. Locke on theFoundation of Morality

• Suppose we take Hobbes and Locke at their word as advertising the use of reason in morality as if by a mathematical model

• Then we can see a important difference between the two • It would account for Hobbes’s secularism and Locke’s lack of

secularism • The basic idea in Hobbes’s account is supposed to be persons’ self-

interest in their own self-preservation; everything else is supposed to follow from that

• The counterpart basic idea in Locke is that God exists and created us; everything else is supposed to follow from that

• Thus, Hobbes’s foundation for morality does not require God’s existence, but Locke’s surely does

Locke’s Deductive Inferences

• A number of things are supposed for Locke to follow as deductive inferences (as with Hobbes): – equality; – independence (i.e., political freedom, and presumably

liberty of action as well); – no subordination; – a law against suicide (e.g., no slavery); – a law to preserve the rest of mankind; – to preserve others in their liberty, health, limbs, or

goods.

Natural Law: Locke vs. Hobbes

• Locke’s is a more traditional natural law theory• Thus, he chooses intellectualism over

voluntarism (unlike Hobbes)• Also unlike Hobbes’s, in that natural law does

not have a theological foundation (unless the Taylor-Warrender interpretation of Hobbes is correct)

• And Hobbes thought that all ethics in the human realm was artificial

Justification of Property: Natural Law

• For Locke, the account of property lies in natural law

• The justification of property independently of the social contract means that unlike in Hobbes:– The state of nature is not a state of war– There are moral principles that govern us

independent of the social contract

What One Owns

• In the State of Nature, one owns:• One’s body• One’s labor• Its product (the ‘mixing of one’s labor’) –

one’s property• In the case of property or product, Locke is

appealing again to the workmanship principle• Unclear how we can own if God owns us – is it

joint ownership?

God Gives the World to Humans in Common

• In Section 26, Locke wrote: “God, who hath given the world to men in common, hath also given them reason to make use of it to the best advantage of life, and convenience. The earth, and all that is therein, is given to men for the support and comfort of their being. And tho' all the fruits it naturally produces, and beasts it feeds, belong to mankind in common, as they are produced by the spontaneous hand of nature; and no body has originally a private dominion, exclusive of the rest of mankind, in any of them, as they are thus in their natural state”

• That is to say, he has given it to all people, including the American Indians. The Dutch. The Spanish. Collectively.

• They are all co-owners of the whole as a whole. But that’s not good enough; we want to be exclusive owners—especially if we want to colonize a new land.

How Do We Extract Personal Ownership from the Common?

• How can I own something? • How can Englishman take things that are

already seemingly owned by the Native Americans?

• For Locke, the answer is simple: – Labor and Industry.

The Apple Example

• In Section 28 of the Second Treatise, he gives the well-known “Apple Example”.

• It’s really an argument about where ownership comes from:

• “He that is nourished by the acorns he picked up under an oak, or the apples he gathered from the trees in the wood, has certainly appropriated them to himself. No body can deny but the nourishment is his. I ask then, when did they begin to be his? when he digested? or when he eat? or when he boiled? or when he brought them home? or when he picked them up?”

When Does Ownership Begin?

• When does the ownership begin? • When he digested the apple? • When he ate it? When he boiled it? • Locke writes: “ … it is plain, if the first gathering made

them not his, nothing else could. That labor put a distinction between them and common: that added something to them more than nature, the common mother of all, had done; and so they became his private right.”

• The mixing of labor occurs when you pick the apple up and thus remove it from the State of Nature.

Same for Native Americans

• This is not a story exclusive to Englishmen. • Anyone can mix their labor.

• Section 26--“The fruit, or venison, which nourishes the wild Indian, who knows no enclosure, and is still a tenant in common, must be his, and so his, i.e. a part of him, that another can no longer have any right to it, before it can do him any good for the support of his life.”

Limitations on Property

• I can’t take what you have already mixed your labor with. First come first serve.

• Spoilage is prohibited; I’m not allowed to take more than I can used before it spoils.

• I can only appropriate something for myself so long as what’s left is “enough and as good”. Notice that these are two separate criteria.

• There has to be some left over for other people. I can’t take it all. It’s not going to be fair to take more than my share.

• Furthermore, what’s left has to be “as good” as what’s taken. I can’t just leave behind the inferior apples.

Three types of things that could be appropriated this way

• Fruit: things that are grown naturally• Beasts: animals, both domestic and found• Land: certainly the most important and the

most problematical because appropriating it requires closing it off and keeping others (namely, Indians) out.

The Source for Conflict with the Natives

• We might ask, how does simply enclosing land provide for ownership of that land?

• On this theory, enclosing the land is a form of “improving the land”, mixing your labor.

• Here a conflict arises: the English had the intent to improve the land, while the Indians did not.

• The Indians had a different conception of land use: they were largely hunter-gatherers so they used land in a more open, communal way. But this did not mesh well with Locke’s conception of ownership.

• This gives the English an automatic advantage over the Indian’s claims to the land, according to Locke’s theory.

•