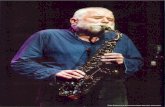

Peter Brotzmann

-

Upload

perpetual-pi -

Category

Documents

-

view

23 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Peter Brotzmann

Heffley on Brötzmann: Charmed like a Snake in a Trance

… only to find himself standing in Wuppertal, on the Übergrunewalderstraße, at

Peter Brötzmann's door, listening to footsteps approach from within.

The weather was much the same autumn balm as in Berlin the day before; the

neighborhood, though… blissfully, quiet-residential rather than noisy-urban. It was

almost twenty-four hours later, he knew, and in a flicker of panic he mentally scurried to

review the time he had just lost (…this was not the first time this had happened to him in

this "field," and he didn't expect it to be the last…).

The memories flashed by like a dream fading in a wake: Dagmar, Gerlinde, and—

delighted surprise!—Lady Europa, the woman he'd seen on the train, making her own

way, so it chanced, to meet Gerlinde, whom she'd called through the national car-pooling

service that connected people driving with people needing rides; some coffee and snacks

with the three women around Dagmar's table, departure from Berlin by car… his second

time out at length on the autobahn, sights of mostly farms and their fields, some factories

(the autobahn doesn't dip through cities, like American freeways)… some talk with the

women, mostly about his impressions of something deeper and more human in gender

identities and relations here than in America, something integrated with a larger

Europeanness that bore the Ami-corporate-pop-political culture like an old building bore

ivy—something he felt (after reading Watson 1992, especially the chapter [155-98] on

the German business culture's more socially responsible, management/labor/government

non-inter-adversarial style of capitalism) would prevail, in the end, like Russia prevailed

over communism in spite of, as much as because of, capitalism (of course—Eros as

social, historical, cultural glue as much as superficial sexual spark, per Van Nortwick

[1998: 118])… mostly silence in the back seat with his thoughts and the sights of the

middle and western states rolling through his virgin eyes for the first time… especially

Hessen, which he grew up hearing about as the land of his ancestors, brought (bought,

mostly against their will, often enough from Hessian prisons) by the British to fight the

rebellious American colonists… just another stretch of rolling green hills and plains, at

dusk, no time to stop… maybe someday before the summer ended, maybe in Frankfurt, to

interview Albert Mangelsdorff, then a day or two extra to see the sights, scour the phone

books for names like Heffley (Höflich? Höfling?), to feel like a prodigal son's great-

great-grandson come home…

The Muses, who lived around Mount Olympus in Northern Greece, were the guardians of study, memory, and song. They inspired the heroes Amphion and Orpheus to conquer life and death by the power of music. Such a myth supported the ritual magic aspects of music common to most primitive and ancient peoples. The Mycanean settlers on the coast of Asia Minor preserved the ancient heritage of the Greek mainland and also incoporated into their culture the many philosophical, poetic, scientific, and musical systems that abounded east and west of the Aegean. But a total integration never occurred, so that certain differences in taste, character, and musical practices persisted in Greek life.

—Scholl and White (1970: 10-11)

The ending of the "dream" lingered even less as Brötzmann crossed (apparently) a

long passageway and was about to open the door: arrival at Peter Kowald's house in the

middle of the night, his friendly greeting, a night in a loft bed in the studio where his

Greek artist wife made her paintings ("Charles Gayle, the saxophonist from New York,

slept here for several months not too long ago," Kowald said… ), a shower, clean-sheet,

nice-bed bliss, up, out, and

"Hallo, Mike," Brötzmann said, extending his hand. Just around the corner from

Kowald, his place was (like Kowald's) a townhouse of two or three floors, his own flat at

ground level. Heffley's temporal disorientation was swept away by the pull of the

moment, and the professional habits ingrained over years of interviewing public

personalities.

The entrance hall, then, re-oriented him, as Brötzmann led the way through it to the

inner rooms opening onto the courtyard where they would sit and talk, to this thought:

"How many times in Germany have I joined someone in their home after what seems like

taking a trip through a little cave tunnel? Both of Dagmar's places, Panajota's, this one—

all designed to pull you into their space like the earth back into its womb (the courtyard),

all folded in with "backs" (walls) to the world, windows facing inward…

Brötzmann's place was different, though, and that was due to Heffley's

aforementioned professional habits. Because once they were seated and beginning to tape

—in fact, precisely at the moment Brötzmann said "Okay," in the particular tone he did,

to the few words Heffley spoke to set up the interview—they were no longer at a table on

the ground floor,

but grounded so at the much greater height of , which I strove to realize as the

setting for all MY interviews with, specifically, the men I had settled on as the

personifications of FMP West (Gebers, von Schlippenbach, Brötzmann, and Kowald) and

East (Petrovsky, Gumpert, Bauer and Sommer).

It is an earthy place, not otherworldly, but that grainy, gritty earth sits high among

drifting clouds, and looks down on the rest of the world as if from sky. It could have been

a mountain plateau anywhere, but in fact it is the ancient Greek place of the ancient

Greek gods. Why there, why them? That Heffley did not know, since it had risen,

Atlantis-like, from the depths of his subconscious, but he trusted he would figure it out

later (and he was right, as I am here to explain it, soon). It was just another one of those

devices—like Lady Europa and the Three Furies—his mind had constructed to frame the

parts of the new culture here that were mildly shocking, or puzzling…only in this case it

was a real place that arose to meet the demands of real time (interviewing).

Those were in fact the demands of performance, much like musical performance,

much like improvisatory musical performance: years of thought and preparation,

background research, focus on a discourse and its participants; logistical real-world

maneuvering to get in a position to sit down at the table with the subject, to be taken

seriously and opened up to, given the benefit of all doubt; finally, a finite, fleeting bit of

(necessarily) scheduled time, in which something magical and momentous can take place

—real communion over weighty matters—or not, depending on the skill and attitude of

the participants. Like a musician entering into a pact with her audience to give it no less

than her best, to know what they want and help them get it, MY interviewees and I were

coming together to meet for an hour or two out of our lives in hopes that we would

exchange their essences successfully enough to convey them to, potentially, the rest of

humanity for all time. Moreover, our chosen means of doing that was not to prescribe and

script it—to write down questions, write down answers, have no real exchange in the

moment unmediated—but to meet as two open minds with a few vaguely sketched routes

to explore, and the power to do so spontaneously, interactively, responsibly and fruitfully

(as, indeed, I am doing here alone with you).

It wasn't even conscious any more—Heffley went into the same trance as when he

played music; pressing that tape recorder button and making his opening remarks to the

interviewee was like hitting the stage of a performance and playing those first few notes.

Much depended on them; the better and more effective they were, the better the prospect

for all that unfolded from them.

Like a trombone, Heffley's tone, affect, as much as his words, signaled to Brötzmann

his invitation to join him there in Olympus; Brötzmann's immediate responsive "Okay,"

through its tone and affect, signaled to Heffley, like a clarinet, Brötzmann's recognition

of the place and a readiness to join him there.

Listen to CD 7/2, track 5

"When you look back on this time from today," I begin, "do you feel the recordings

of the first-hour period—Machine Gun, For Adolphe Sax, The Living Music, European

Echoes—are all good documents of the music as it was emerging live?"

"Yeah, even though some are not very well recorded. But especially Machine Gun is,

for that time, a classic. It documents the feeling perfectly. There are today a lot of young

people interested in this type of music, and to find out about the European roots of it, I

think Machine Gun is a must for them. It's still the best-selling FMP recording. You

know our business: you sell five hundred or maybe a thousand records, then after a

couple of years it's over—but Machine Gun just keeps going. Some of my or my friends'

recordings disappear somehow, but that one really keeps going through these thirty,

thirty-five years."

"It's clear that its success must please you as one of the musicians. Is it also such a

success in you own inner musical life? Do you still hold its presence in your mind, maybe

listen to it now and then and hear new or fresh things in it yourself?"

"Yeah, it is like that. I mean, I'm now thirty years older or so, and I've done a lot of

other work… but, you know, in this period of life one doesn't often have such a thing to

look back on; I feel very happy that I did it when I was very young. It was not just the

music, it was a kind of feeling of the time that made all of us enthusiastic, happy.

"I always see jazz music as coming from working together. True, there is a solo part

to the thing too, but what always fascinated me about it was the collaboration and

cooperation with other people from other countries, other parts of the world—it doesn't

matter at all. We all learned that very early in those years, and I think to keep going as we

have on that idea alone is already something important. And the music itself, beyond that

idea, I think is a perfect representation of that period: Europe in 1968, '69, Paris, Berlin—

it was happening. Machine Gun I see as belonging to those years. I wouldn't say that I

planned it as a kind of political statement; we just lived it, in that time, and we made

music, so we took our inspiration out of the situation."

"What's interesting to me is that you don't look back on it as something from youth

that you've grown out of; it's something that stands as important now just as it did then.

So I wonder—if you keep this vision in your mind for so long, when you hear this early

music now, what new things do you find there that you weren't necessarily conscious of

at first?"

"Well, I should say first that I don't typically listen to my own recordings, but

sometimes I have to, if I give interviews in radio stations, for example—which has

happened quite a lot in recent years in universities in the States, and of course Machine

Gun is on the table… What I still like most about it is the feeling of commonality, a kind

of vision of sound we all shared. As you know, I haven't really been a guy so keen on

subtleties, too-sensitive things. I mean I've changed a lot since then, hopefully, but at that

time I had an idea of sound, of complex sound. It didn't really matter so much what

instruments made it—saxophone, basses, whatever—it was just a vision of complex

sound. And I still have it, hopefully in a different way, because I've learned a lot in these

past decades."

"I'll ask you more about that. I can tell you that when I first heard Machine Gun,

being around the same age as you, growing up in those times in America, exposed to

Coltrane then, and Ornette Coleman, and Albert Ayler, that the energy you guys had

seemed to be the same kind of energy, but it felt like it was phrased, and shaped, and

flowing more from the breath of the horn players than from the rhythm of the drums. Not

that the rhythm wasn't there, but in the music I was used to there seemed to be this

ongoing river through the drums…"

"Yeah…"

"… but what I heard everybody doing here seemed to be more based around the

breath—like, how long can a breath last, and what can happen in a breath?"

"Yeah. Of course, the horn players—and I would say especially the three horn players

in this part of Europe, Evan Parker, Willem Breuker, and myself"—the three on Machine

Gun—"formed that kind of feeling in those years. Of course, we had the drummers—Han

Bennink, the young Paul Lovens coming up, Tony Oxley (who always was working in a

little bit different area of the music), Johnny Stevens was still alive… so it was quite an

exchange of language between the drums and the horns. Evan is, for the English scene, as

important as Willem for the Dutch and, hopefully, as I am in Germany for this kind of

thing. We played the horns extremely differently from anyone before us, as well as from

our peers at the time in the States. All my American friends, whom I like very much,

have always played the horn differently, because they have another view of the

instrument, from another tradition. Of course I like Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins,

Sonny Rollins and even earlier players, but I can't say I have it in my blood. I learned and

listened—but if I even talk to younger people, American guys, 35 or so, I feel they have

it, this feeling, black or white, it doesn't matter so much, because they are American

(from my point of view)."

"Did you spend a lot of time as a young player, when you listened to American jazz,

trying to get that American feeling?"

"Oh yeah. You know, after the war there was just one radio to a family. And I was

going to school, and every night, at 12 o'clock, we had Willis Conover's Voice of

America music broadcast. Of course, I should have been in bed already, but I sneaked

downstairs and listened like this to Willis Conover. I was very hungry for information

about the music, because we had very few of our own radio things like this here, and they

were quite old-fashioned, and Willis Conover gave us new, fresh information.

"Then I started a kind of jazz club at my school. I was about 13 or so, and I played to

records by Kid Ory and Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong and the Hot Five, all kinds of

records. Then, the clarinet player in our school band graduated, and the clarinet was

school property, so I grabbed it, and started playing to the records I had. I was quite lucky

that some older guys who had studied at the very famous Folkwang Hochschule in Essen

let me sit in with their group, and after a couple of weeks they said, 'Okay, let's try this.'

So I was in a band at 14 and 15 with players who were 18 and already quite good. One is

a professor now, and he is a drummer in a symphony orchestra. We had a kind of swing

band, playing night clubs in the area…

"But eventually, of course, I realized that I wasn't a black man, wasn't even an

American, I had my culture here… and, you know, hand in hand with playing music was

already in my very young years my involvement with painting.

"I left school in my hometown of Remscheid to come over to Wuppertal to this art

school—which is now part of the university here—and I studied graphic arts and

painting. My other fruit was in that area. At that time there was a very good gallery over

here, the Galerie Parnass. The guy who owned it was really a fantastic guy. He organized

the most avant-garde stuff in these years that you could find in Europe or America. The

first big exhibition of Nam June Paik happened here, and Beuys, and the Fluxus

Movement—it all happened here, some of it for the first time. To this day, I'm still very

good friends with Nam June Paik; he was a big influence on my thinking and doing.

"At that time, I thought I would earn some money with graphic art, so I jumped into

the painting. I had my first exhibitions, and some were quite successful, in a way

(whatever that means). But playing music increased, and I was involved much more in

that. I like to have a real audience in front of me, I like to travel, and I found that much

more interesting and much more serious than all this work in the art field… I quit school

in Wuppertal when I was 17. I went to this art school here, and the first guy I met who

played music, or wanted to play music, was Kowald. So we stuck together for the next

ten, fifteen years…"

"Wuppertal is written about as on an axis with Berlin in FMP history. Peter Kowald

just did that major project Ort, conceived around the community and locale here. You

and he, along with Hans Reichel, have lived and worked here a long time. I've even read

about a 'Ruhr Valley' sound. How does the character of this place really relate to your

music?"

"This town is a very artificial thing. The two biggest parts of Wuppertal are Elberfeld

and Barmen, a bit more to the east. It's really a row of villages along the Wupper River.

Then, to please Kaiser Wilhelm, they built up the Schwebebahn (a hanging overground

train), and then they thought, 'Okay, we are not just villages anymore, we have to be a

proper city,' with this new 'Wupper Valley' name. So this town has no center, in a way.

"We have had interesting people living here at any given moment. Very strong-

minded, some of them not looking left or right, just doing their things, and we had a lot of

quite rich bankers here, and these were very, very open, and they looked around for art—

like the Impressionists and Expressionists and all from that area. So our museum, for

example—the Von der Heydt—is named after one of these guys. It has a lot of really

beautiful art from the early years of the century, in stock—it's too small to show, but they

have it. So this town does have something special.

"And you know it was well known before the first and second wars as the town with

the most religious sects. You have different churches, not only the Catholic and

Protestant but all kinds of small shit," he laughs, "so the people here are kind of different

from others. It's all mixed up.

"You even have two roots of language here. You have the Western part, that of the

Rhine people—from Köln, and Dusseldorf—and the Barmen, in the east, goes more to

the woods and is a bit more rough language, toward Westfalen. So Elberfeld and Barmen

really meet at the language border of these two groups. But of course through the war and

after the war it's all mixed up. You find from time to time old people in the bar just

talking original dialect, but they pass away, of course.

"For this music, Wuppertal has always had either me or Kowald really doing

something. Kowald is different from me. I live here, and in the early years we did our

activities together. But nowadays I just live here. I play once a year, or twice, and that's

enough. Kowald plays all around the year everywhere and is involved in a lot of city

activities, which is not my cup of tea, I must say. I like to come back, I prefer to go," he

laughs, "and the rest, as you see, the sun is shining—a very rare situation this time of

year."

"How is the relationship between music and visual art for you? Have they always fed

each other, or do they do different things? How does that work?"

"It would be too easy to say that in both fields you work with colors and this kind of

thing. That might be very obvious. I think being busy with the (let's call it) fine art—the

paintings and graphics and woodcuts and working together with people like Nam June

Paik, like when I helped him as a kind of assistant in a lot of exhibitions here and in

Holland—that always gave me a lot for the music too. My decision was easier for me to

just do my thing, or find out what it is, and coming as close as possible to that. I'm still on

my way, step by step; the steps are getting smaller," he laughs, "but that was really a

good school for me, to have that other side. I realized things earlier and faster than other

people, 'normal' musicians who studied, formed bands but had no idea what was going on

in other fields, or in the world at all. But for me—and, in a way, because Kowald was

always with me and was interested in this kind of thing too—I think for us it was not so

difficult to leave the solid jazz base. In fact, it was quite logical for us to experiment with

other things, other sounds, combinations, other ways of thinking about music. So that was

very important for me."

"Do you remember how you felt in those years in terms of being surprised as to what

direction the music was taking? I'm thinking of the way it was called the Emanzipation in

the media, this European style that was emerging. Did you think of it that way yourself?"

"I think I was one of the very few Europeans who had, from the very beginning, a

really strong feeling for American jazz music, and for the musicians I met. Persons were

always the most important influences on my music anyway, whether it was Don Cherry

or Steve Lacy, or even—a man I shook hands with when I was very young, when he

played here in town—Howling Wolf. His hands were huge, and mine were so small. I've

always been impressed with this kind of thing.

"But there was of course a very strong feeling against Americans in these years, and

quite a lot from English musicians. I don't know exactly why that was, I never had it, but

I remember in the early years—late '60s, early '70s—there was quite a strongly expressed

opinion against including Americans on festival programming. Peter and I never had that.

It was we who set up the first years of the Moers Festival, and we brought everybody

who was available there. We didn't pay someone to come from New York or so, but we

could ask our friends like Frank Wright or Steve Lacy or Don Cherry, who lived in

Europe, 'Could you pass by if you are on your way up to Scandinavia?' and they all came

—for nothing more than a comfortable stay and more or less pocket money. But they

helped us get the thing together, and I still have to thank these guys."

"I notice on the FMP catalogue, though, that there aren't too many

European/American collaborations until into the '80s."

"That might be true, because after the Machine Gun and Globe Unity days there came

a really strong period of working only with the trio, with Fred van Hove and Han

Bennink. That went on for more than ten years, and then a few more years with Han as a

duo. We invited guests, but mostly European guests, I think, and the American contacts

we had at that time, there are no recordings. My brother, more or less, was [American

saxophonist] Frank Wright. I organized a lot of things here in Europe, mostly radio

stations—NDR must still have some tapes—I don't know, for whatever reason there was

never a chance to decide 'let's record that.' That was in the early '80s."

"At which time you recorded with Andrew Cyrille in a duo, and others after that. So

there's a network of American players playing with you in Europe, and then in recent

years you've been coming yourself a lot more to America. So let me jump ahead and ask

you what exactly you're doing right now. What are your most regular sources of work,

your usual circuit of performance venues, and the people you currently play with the

most?"

"To jump ahead to that, I think I must say that the time is over where you really work

with just one group, as I did with my trio then. I think all of us have to look around now

for what is possible. It's still the same situation. We don't get rich. The food is better than

thirty years ago, the whiskey is better," he laughs, "and the sun is shining today, so I don't

complain at all. I decided, and that's cool.

"So what am I doing? For about eight years, I think, since the first time I met Hamid

Drake in Chicago and played, as I recall, a two-hour duo, it was a kind of friendship from

the first second. I would say he is the main important man in the last few years for me.

Then, I have an old Japanese friend, Toshinori Kondo, and even before I worked with

Hamid I worked a lot together with William Parker. So we came to the idea of forming

the quartet. Which, I must say, I would like to work with much more."

"The Die Like a Dog band… "

"Yeah. But it costs so much to get Kondo over, and the two Americans. The people

nowadays, they don't want to pay… "

"You mean the cultural ministries?"

"Yeah, or the radio stations, or other promoters, concert people—so the quartet is

happening very seldom. It's a pity. I hope I can put it together for this fall, for the FMP

Total Music Meeting. If we did a concert it would of course be recorded.1

"I had another experience last year which I liked very much. Along with Hamid

Drake I collaborated with a Moroccan guy, Mahmoud Gania. He plays the guembri, a

kind of North African bass-stringed instrument, and he is one of the wellknown people of

the Gnawa music. Gnawa is played by black Africans coming mostly from Mali, or

Senegal, as slaves. The Arab people brought them and couldn't sell them, so they stayed

there," he laughs, "and they developed their own language and their own very interesting

rhythm-oriented, very driving music. That is another thing I would like to go on with."

Listen to CD 7/2, tracks 6-7

"Is this the frst collaboration you've had outside of European and American jazz

players, with a non-Western tradition?"

1. They did, it was Little Birds Have Fast Hearts. British journalist Steve Lake and I

wrote the liner notes. Lake points out, correctly, that the difficulties in booking a group with members spread around the globe stem from far more than funding cutbacks in a given locale, are in fact symptoms of the occupational hazard that is the globalism to which this music itself has evolved.

"Yeah, if you don't count the Japanese. I've gone there a lot for about seventeen years,

and I've played with nearly all Japanese musicians, more or less, in this kind of music.

But, of course, they are now distant from their own tradition, most of them, so they look

really more at what is happening in American jazz much more than to their own tradition.

Maybe it's coming again, but when I first went there seventeen years ago they were all

obsessed, first, with what was happening in New York, and second, in Wuppertal. Those

were their sources."

"It's an interesting scene in New York now with the Japanese presence. A lot of

students and younger players are active in both the bebop and improvised music scenes.

So you got no real non-Western influences from your Japanese collaborations?"

"Being patient," he laughs. "You have to get that, because you can try to learn about

who they are, but even old American professors who stayed there after the war, who

speak perfect Japanese, say 'The more I learn about it, the less I understand.' So you go

your own way, so that's what I did. You be very frank and open, but very true to your

own way, and I think they appreciate that very much.

"What did I get back from them?" A pause. "There are three players I like to work

with and I learned a lot from, but I'm not sure I can say what so concretely… And

Toshinori Kondo, my oldest friend, is not really Japanese. He says so himself. Even the

Japanese people in the street, when we pass by, they look at him much more than me. For

them, Kondo is not really Japanese. He doesn't behave like a Japanese," he laughs, "his

behavior, his face—he comes from a small village near the Atlantic, and his father was

one of those guys who came out years after the war was finished from some island

mountains, not knowing that it was finished. These people are quite different from people

in Tokyo," he laughs. "But he's really a very worldly guy. He has a very strong tradition

in Japanese Zen Buddhism, which you find out when you sit with him through long

nights. Then it starts to come out.

"And then, for the last two or three years, I've worked with a guitar player named

only Haino—a kind of figure out of the avant-garde rock scene. He's a crazy guy; we did

a CD where he just sings and I play the tenor. I don't know if I like it, it's very strange.

But he's a guy who's very, very strange. He doesn't speak, his manager has to be always

around to translate. But after a time I was on tour for four weeks last year, and I realized

he understands, and after two or three weeks we started to speak English from time to

time.

"So the people there are different, really, not as open as I know Americans are. You

really have to be patient. I mean I was sitting with my third friend, the drummer Shoji

Hano, in an auto for nearly two days on the road in Japan. He had something or other on

his mind, and he didn't speak a word to me for the entire time. And if you don't know, of

course, you doubt; 'What's happening, tell me.' I mean, if I would sit with you for two

days and you feel bad, I would see and ask you and I think that somehow I would get a

kind of answer. And I knew this guy well at that point; he had stayed here in my back

house for three months, we're friends. What can I say, he didn't speak for two days."

"And you never did find out why?"

"No, not until two years later!" he laughs.

Listen to CD 7/2, tracks 10-11

"We've been laughing about it, but is there an aspect of your musical work that

benefits from such patience, perhaps especially as you get older?"

"Oh yeah, oh yeah," he says. "I realized that myself, and even old friends from the

very early years who hear me now, they say that too, and tell me how different it is from

the steaming years. That doesn't mean that my thoughts are not steaming, or that if I'm in

the right mood I don't still like to play my ass off and get the guys moving… but of

course I learned there are other ways to play intense music. Especially the years I'm

working now with Borah Bergman. I think I always did know that, but he brought it out

of me with his very facile piano playing to do things that I forgot I could do—especially

playing clarinet. I'm not a good clarinet player, but I like the instrument, so playing it

with him I like very much. It's sometimes very, very intense, but also a very minimal

thing. I think Borah is a perfect guy to get that out of me. Hamid Drake is also drawing

out special things when he plays, for example, tablas or frame drums. But I think I learn

from nearly all the guys I work with."

"You've done four solo recordings for FMP. Did you develop this solo work as a way

to develop something on the instruments that you couldn't get to in any other situation?"

"I think the history of each of these is different. The first thing I did to show the range

of instruments I was playing. I wrote little pieces and tried to work with the material. The

second one, 14 Love Poems—here is something I forgot to mention on the record. One of

my favorite writers is the poet Kenneth Patchen."

"Ah ja, from San Francisco."

"Right. And he wrote a little booklet called 14 Love Poems. That was for a long time

my very favorite book to travel with, so I had a very personal connection with it."

Listen to CD 7/1, tracks 3-4

"So this was an example of a piece of literature shaping the concept of a recording.

Do you do that often?"

"I also did it with No Nothing, because at that time I was trying to read Oscar Wilde

again, and, you know, with my English it's not that easy. I travel with books from time to

time, I always have a special book I'm busy with. So at the time I recorded that I was

reading Oscar Wilde, and all the quotations are out of his work."

"Is this then a special approach for solo work?"

"Yeah, it's a kind of more intimate thing, to come closer to another medium, in a way,

and to another person, which gives me something for my own work."

"Do you write out your solo pieces in music notation?"

"No. They're in my mind, because I'm not a good reader. Sometimes I put a few notes

down just to get it in my mind, but then there it is, that's it. On the very first one, I did

make little tunes to play, and sometimes to remember the pattern or so I sing it on the

tape, or I write the notes down. The thing I remember about Oscar Wilde was that it was

a lot about landscapes and light and things. That is a kind of connection to painting, too.

Landscapes have always interested me—the light, the sunrise, the changing colors of the

sea, this kind of thing."

"Speaking of notation and organizing, how did you fnd the experience of playing in

Cecil Taylor's European Orchestra, on the Alms/Tiergarten (Spree) CD? I know how he

orally transmits his patterns of pitches a note at a time to such ensembles."

"Yeah, but if you know his work, and the way he works, it's not so difficult to

understand. He, I realized, is thinking in scales, and in movements, and it's quite easy to

follow—especially in this big band, where you really have to make it concrete what the

players have to do. I mean, he was always lost when—I was standing right next to him at

that session, near the piano, and I did my best to follow his instructions, but sometimes I

tried to play my ass off, and he didn't like that at all," he laughs. "People think when they

work with such a 'great one' that they have to do what he says. And I think he enjoys it

much more when there's someone who kicks his ass. I think he needs it; otherwise,

people are so devout, and act like he's the grandfather of everything. But he is not like

that, we had a lot of times just drinking and hanging out, and it was very beautiful and

informative to hear him tell about his youth, and the cotton fields and his grandma. Nice

things. We have a very distanced friendship, in a way.

"I would like to work more with bigger groups, to try and find a way of organizing

things."

"How would you do it differently than others?"

"I think the first thing you have to accept is that every person is playing in the band as

a really free individual. He has to decide if he wants to play, or what he wants to play. On

the other hand, you need a kind of discipline with eight or ten people; then, a little

structured information can help to make big things even bigger and more concentrated.

"Of course, if I ask eight or ten people to play for a certain project, I have a certain

idea of what it should be, so I try to find ways to get the guys playing in the way I want to

hear the music—without cutting everything down, just to find a way to let them grow the

possibilities, of sound, of their very personal sounds, and of the band sound too—which

always requires more time than you ever have, you know."

"Did you do something like that with your ICP tentet recording?"

Listen to CD 7/2, tracks 12-13

"Well, that was different, because Misha's concept was to come with a certain song,

or organization, or structures, but you know the Dutch have a certain way of using

melodies, their own folk songs, in an ironical way, and Misha is a master at doing that…

The Dutch scene with collectives, especially Willem Breuker in the late '70s, early '80s,

was kind of fresh, in a way, and a lot of other musicians—Maarten van Regteren Altena,

for example—and then all the Amis lived in Rotterdam or Amsterdam. It was really

happening, but now… the government cut the money about ten years ago, so there aren't

very many places to play anymore. Whenever I meet Han Bennink he's always

complaining about the possibilities in his country. Misha is not doing very much because

he prefers to sit now in his chess café and play chess, but from time to time he plays. Han

is, like me, more or less in foreign countries. You know, if you're just a player, you don't

get much help from the government. But if you can call yourself a composer and write

some so-called compositions, they pay quite well enough. Like Willem, or Maarten—he's

just sitting at home and writing piece after piece. If he is content with that, it's fine. But I

wouldn't be interested. For me, this way of life—traveling, playing, seeing other people,

working with them—is what I really like to do."

"Naturally there have been high points and lulls in terms of activity in the improvised

music scene over the last thirty years. But I wonder from what you're saying if overall

you think there's been a decline in understanding of improvised music as a legitimate art

form. A lot of American improvisers—indeed, many of the African-American guys who

pioneered it—have become 'composers' for that very reason, in part."

"Sure, and I can understand that, because to survive over there is much harder than in

Europe. But I think in a way I'm very old-fashioned. I'm just a guy who likes to travel, as

I said, to see the world; to work, sure, that's the main reason, but it depends. If you look

at Bill Dixon… of course, he's really an older man now. I'm not a young man anymore,

but he's quite a bit older, and of course he likes to teach at his college, and if he travels

around the world he's doing his lectures, and playing from time to time a little bit, so,

okay, it's not his cup of tea anymore; his college life and his compositions and his writing

about music, I think it's much more important for him."

"But you seem to have succeeded in your recent years in branching out from your

FMP history. The work with Borah Bergman, and Thomas Borgmann, on different

labels…this trio coming up at Mulhouse, with Majid Bekas. Is he also a Moroccan

player?"

"Yes, a kind of replacement for Mahmoud. It's a risk for Hamid and me, but both of

us, we didn't want to lose connections." (Mahmoud was unavailable for this particular

date). "I like this kind of music because it goes; and these people, they play for hours, for

nights. In our way, Hamid's and my way about thinking of the timing of tunes or pieces

you play… after the European, or American way, it's the same—after a time, you have to

come to an end. But they never do—they get in a kind of trance. Mahmoud's wife is a

dancer in a kind of dervish band with him, and it goes on for hours and hours and hours."

"One of the things I've really been fascinated about in looking into all the FMP

records is this sense of timing. When there's no predetermined form and everybody's

working their material in the moment, I notice a certain biological clock coming to the

fore."

"Yeah, that's what is, I think, so fascinating for us, because through all these hundreds

of years we lost it, in a way, in our 'Kul-tur'"—a sarcastic tone—"and all that kind of

bullshit, and I think that's why my inner feeling is such an interest in that. Through

playing, sometimes you come to a point where you feel it could go on and on… but I

think people have different pulses, so…"

"But what you're saying is that for yourself right now what's interesting is the idea of

going for longer periods of time, with this Moroccan music?"

"Yeah. I mean, l'm not into this trend of everybody playing ethnic music. That started

a hundred years ago with Ginger Baker bringing all his African friends and women here

on stage, and it was wonderful, but nowadays…I think it's all a terrible

misunderstanding… a kind of commercial business way of thinking. That's not my

intention here. I'm just fascinated by the way the whole thing is going, with no

problems…mind, a body, and all of it is going in one kind of movement."

"Has this trio played much yet?"

"We had a tour of twelve days, something like that. It started at the Peter Edel

[Kulturhaus]—I mean, Mahmoud's a funny guy, always smiling, really dark black, one of

these really friendly guys—and so we said hello, onstage, and we played for a long time.

There was no recording of that, but I think for the first concert it was already perfect. It

went on and on and we had to travel, everybody was fucked up, having to jump on the

stage after sitting ten hours on trains, things like that. Really hard work… but as soon as

it came to the music, on the bandstand, it was no problem any more.

"I think it had a lot to do with that guy just sitting there and being one in all, his

appearance. You could feel it, in a way. And Hamid is the same, in a way. Mahmoud and

Hamid fit together so well, getting into such a mood of going and going—Hamid is a

maniac anyway—so I was the guy who, besides going with them, from time to time I had

to—disturb them," he laughs.

"To get them out of the groove?"

"Yeah, it was really going far—really strong feeling—but sometimes, okay, that's my

Western education, my roots I have somewhere."

"Did you also play the role of the one who brings things to an end?"

"Yes, I had to. I had to. I met Mahmoud the first time in France, in a small village

near Grenoble. Some artists made some sound sculptures out of wood and other

materials. They asked me to stop by and play with them, and there I met Mahmoud. The

next day we were free of that program's festival, and we played an afternoon concert, just

us two, and I thought, 'This is it.' It was fitting so well together."

"What's interesting to me about this is that your music has established itself as

something with a European voice, but also with good connections to American jazz

tradition. I don't know so much about the Japanese relationship, but you've explained it

well. But in recent years, for example, you've started playing also this Hungarian

instrument—"

"The taragato."2

"—and you've just told me that you're not so interested in the 'world music' trend.

Peter Kowald has also been expanding out into other non-Western directions in recent

years. So when you play with this trio in Mulhouse, it will be a freely improvised

situation, with no predetermined musical strategies, right?"

"That it will."

"And it will be one long set of a continuous stream of music?"

"It depends on what we want to do. I can always stand back and get myself a drink. I

need it; a horn player blows such a lot of moisture out of his body, he has to have it back.

The way we did it with Mahmoud, we played as long as we felt the tension there, and

Hamid and I, we know each other so well we know when is the way it should end,

somehow. It ended up at a lot of concerts that Mahmoud went on playing his instrument

2. Brötzmann to Witherden: "About eight years ago I played in Hungary and met an

instrument maker and repairer. He asked me to his workshop, and he had a row of taragatos. I knew this kind of thing existed because years ago I met a Hungarian guy playing in a New York street on a fantastic instrument and I asked him what it was. Anyway, I was lucky to find this one in Hungary." (41)

alone, and singing his Moroccan songs and, uh—yeah, he didn't see a need for himself to

stop. So he brought us in after a time. I mean, if it goes, and if it goes in a natural, logical

way, then I think it's fine."

"Did he ever make the choice to stop and let you and Hamid take a duo?"

"No."

"Never!?" I laugh.

"Out of the question," he laughs.

"And also with Beka, he will play continuously?"

"Yeah, the music is entirely unstructured, the rhythm is always changing, the sound is

highly monotonous, the tunes are also very similar. It's a music conceived to last for a

day, a night, the next day…"

"So then the Moroccan players understand that this is a European concert set of two

or so hours, so they play that long, more or less arbitrarily for them?"

"The newer player for this gig, I know from his history, is more oriented to Europe.

He's also a bit younger, knows more about the culture here; whether that's a good thing or

not, I don't know." He laughs. "We'll see."

"It reminds me of when Coltrane frst started playing his long sets, and how the idea of

trance came into the music then. Will you be playing taragato much?"

"Yeah. I think it's the perfect instrument for this trio. During the last two or three

years, I come back much more often to the clarinet too. But the taragato is a perfect

thing, because it is very simple, and you know the history of the instrument is that it's

coming through Hungary, Rumania, through the Turks passing by on their way to

Vienna. The Turkish musicians played it in earlier years not with a wooden mouthpiece

but with a brass mouthpiece. That means, you know, all kinds of horn instruments

coming from the Far East—they have the same shape as the taragato, the conical shape;

they are played in the very early times with a brass mouthpiece. Monks in Tibet, for

example, still play the long, big horns with a kind of brass mouthpiece."

"What kind, exactly? Something like a trumpet?"

"Yeah, but with a much narrower cup. After that, coming more to the West, some

other folks put on a double reed, and the Hungarians put on a clarinet-like mouthpiece.

But the sound still has a very nasal kind of sound from all this Oriental sound feeling."

"It seems to me like your development as a tenor saxophone player, or reeds player in

saxophones, has kind of turned through this Moroccan music and this Far Eastern

instrument into the tradition of horns in shamanistic cultures and musics. Is this a

direction you want to explore for a while as a horn player, more than the fingering and all

the notes and so on that came with Western instruments?"

"Oh yeah. I never was a world champion in all the notes and that way of playing. That

never interested me."

"How did the fall of the Wall and subsequent changes in Germany affect your life in

music here, both the spirit and the business of it?"

"I don't think it affected the spirit at all. I think we had enough contacts established

early so that when the Wall tumbled down… I think we were really some of the only

people who knew what was going on in this country about the daily situation, the daily

life of our comrades there. All the speeches after the Wall fell down from the politicians,

you could see they never had been there before. Maybe they'd stayed a day or two in the

one beautiful hotel," he laughs, "but we knew the way of life there, and not all of it was

so bad, at all. But the fall of the Wall didn't touch my musical way of thinking and work,

no.

"It was for me—I always liked to go over there, and I think I was one of the guys who

went over whenever there was a possibility to play. I think I'm a kind of very Prussian

guy, my family comes from the East, and both of my family roots are there, my education

is like that, and the language I think is a very important link, and landscapes, and history

—so I always was very keen on going there and seeing things, and people, and seeing the

problems.

"The only result for us as musicians is that we don't work over there so much

anymore. After the Change, the big festivals we had before—in Leipzig, Dresden or

whatever—immediately switched over to the Herbie Hancocks and American software,"

he laughs, "and we had no chance any more. I still have connections, and I will go in

October or November for a couple of days again, but the good old days when you could

really go from Rostock to Sud in the south and criss-cross from Frankfurt-Oder to

Magdelburg and spend fourteen days there playing every night—this time is over. The

people, of course, have other problems. It's now getting to a point of 'normal,' like in the

West. Here in the West the situation is not so good either. Most of my work I do in

foreign countries."

"What are the other places you play the most at this time?"

"It's always changing. As you know, I'm going quite a lot to the U.S.; sometimes a

little bit of Canada is connected, Japan, every year for a month or so..."

"In the U.S. it's usually New York, Chicago . ."

"… and Atlanta. I've built up some connections traveling around too; there are big

audiences there. It's very funny, because it's always a money problem, because you know

the money for this kind of music… you're lucky if you bring a couple of dollars back

home. Western Europe, Eastern Europe is the same money problem, because I don't want

to be paid in rubles; I can throw these away, or give them to an old grandma on the

corner, you know…"

"I've noticed that the players from the East are, if anything, a little more

understandable and accessible to American jazz-listening ears than those in the West.

Who are some of the players in the East that you've worked with the most? I know you've

worked with Günter Sommer a bit."

"Yeah, we tried a trio with Uli Gumpert about five or six years ago for a short time—

that was right after the Wall fell—and Hannes Bauer, the younger brother of Connie

Bauer, I like very much, and he was always in my bigger groups when I needed a

trombone player. Uli is a very sensitive guy, and a very good pianist…I have the feeling

that he has his problems in finding his way in this new situation. He isn't playing too

often, I think, and I don't know how he makes his living. I think he did a couple of TV

series productions, wrote some music for that—but I think the guys… couldn't make it

here so well. "

"Living here in Wuppertal is a trumpet player—Heinz Becker—you know the name,

I'm sure—and, as you know, trumpet players are very rare in this music, and he is a good

one—at least he was a good one, in the GDR—and he came over before the Wall fell

down, and…he couldn't make it here. I mean, I tried to help him—everybody tried to

help him—but nothing at all. I don't know…"

"A psychological thing?"

"I think so. Klaus Koch, for example: an excellent bass player, but he stays at home,

works only with old friends; he never was able to make it in the West. Hannes, the

trombonist, I think he was young enough at the time we first came to the GDR; he was

very young, had just finished the army, and he was playing in a very special band over

there—so he was open already and could come over and get a lot of ideas about how it

was going here. Connie always had, from before, his connections, especially the

Scandinavian. But some of them just don't know what to do."

"Much like the problems the Eastern people as a whole are having?"

"Yeah."

"You did this Free Jazz with Children. Have you generally been involved with

bringing improvisation into an educational setting, or with private lessons or such?"

"No, that was a part of a summer holiday program of the Academy of Arts. In those

years we had quite a good connection with them, and they asked me and the trio to try

and prepare instruments and simple situations for amateurs, to make some kind of holiday

activities for some kids interested in music, from ages four to fourteen. Some could play

instruments already; we said yes, because it was a job and it was paid. At that time, the

lady who was manning the music department, she was really so very sweet—we all

wanted to do it. And, you know, in these years Berlin still had some money for these

kinds of programs, education, jazz in schools.

"I remember a time, in the night, Misha, Han and I played in some clubs, then just

took a shower and went to some school concerts in the morning at 9 a.m. or so. So we

made some instruments, some very simple things. We had a couple of prepared pianos,

we had all kinds of little things you could make noises with. We had some real pianos, so

some nice young ladies could play the Moonlight Sonata, things like that.

"We were busy all week, and in a way it was very nice. You could see that the kids

had no idea about instruments, just jumped into everything. They tried to play, organized

little groups, and we played a little bit around. The interesting thing was that the nice

young lady could play, for example, the Moonlight Sonata, and after seven days she still

was sitting alone there playing the Moonlight Sonata," he laughs. "So it was a nice little

example of social behavior and making things possible. What can you do with a young

person, with parents and teachers already; they get to some point where they never will

get away from that nonsense."

"So that's not really been a part of your musical life."

"No, it was a nice interesting week, because you could study human behavior, and we

tried to leave it open as much as possible. Or was it so nice? Anyway, it was interesting.

For the last concert we invited Don Cherry and we had the afternoon concert with the

kids—twenty-four or so—and the trio, and Don—and Don, you know, with kids, always

was something, you know," he laughs. "We played a little, kept very in the background…

Don and the kids played some songs, and I tried my best not to blow them away, he

laughs.

"But then, I had time enough to watch the parents who attended, family friends, or

whatever. They were so fucking stupid. Whenever they saw that their son or daughter

didn't assert themselves enough, they said, 'Hey, go on, get up there, work!' you know.

Oh-h-h-h," he moans, "so it was…we finished that after a time and played quite a nice

concert with just Don and the trio.

"But no, for me, and I think for all of us, it was mostly just a nice study in human

behavior."

"When you think about the whole thirty or so years as a saxophonist in improvised

music, what do you think of having learned sheerly in terms of your relationship with

your horn and music, in terms of things like breath, fingering, tone, whatever aspects you

may have noticed?"

"I remember the first time I met Evan [Parker], and Evan heard me playing on a very

bad old saxophone, very cheap shit, but he said, 'Hey, how do you make such a sound?'

Because at that time he was just coming out of the very normal early Coltrane school, and

he had a completely different sound from what he developed after that. He said, 'How do

you make it?' Because my embouchure was totally wrong in terms of formal conventional

training; I still blow it very open, I don't press so much, I let it vibrate much more and

things like that. So for once in my life I could tell Evan a little secret! I got a lot back

from him…"

"I had a good interview with him in Nickelsdorf, and he told me about that time, what

a revelation it was for him. How, then, with your relationship to your horn, as your body

has aged, how do you approach it differently?"

"As soon as I get the horn in my mouth and feel it and have it close to me, it goes. But

I must say that all the traveling—l'm not thirty any more, and it's not easy to accept that

sometimes. Sometimes I feel like it, but it's not the same. I think all of us older guys, we

have to take more care of our health much more than even ten years ago, or fifteen, but

it's hard work, and it's stress, and it's all kinds of really heavy shit (laughs). As soon as

you play and as long as you take care, a little, about the body—and the drinking so much

is not possible any more. I still like it, but for work, it's not possible."

"I notice you're not a smoker."

"No. After a nice dinner, a cigar from time to time, maybe once a week, or sometimes

once a month, but that's it. I was a heavy smoker, heavy Dutch European shit, heavy

black stuff, and there was a time I started to feel pain in my lungs, so I could decide. No,

there was no problem with that."

Listen to CD 7/2, tracks 14-15

****

Brötzmann told Witherden he likes "to be totally pumped up after a gig, so the mind

is empty and the body is falling apart" (41). Heffley is in that state himself now, as I

dismount him after his own long set with Brötzmann. I let him linger as long as he wants

here in Olympus to finish his work—collect himself and his thoughts, organize the

interview material to his tastes. I feel real affection for this old horse. How many others

would have been psychological and physical wrecks at this point in their lives, having

been ridden so relentlessly for so long?

The earthly phenomena housing these numinous Olympian moments are the Greek

restaurant around the corner from Brötzmann's, then a ride on the Schwebebahn, the train

hung on an overhead rail directly over the Wupper River, whisking MY horse like some

Valkyrie over the Rhine, while he muses over and sorts through his work.

Every word is gold, at first; as in a free-music gig, whatever happens in the time it

happens seems sacred, significant, obsessively fascinating. As time passes, even the

artist-shaman in him that would have snarled like a bitch protecting her pups at any

attempts to evaluate, judge, interpret, claim them… well, let's say even the bitch assesses

those pups for their (and her) readiness to leave the teat and take on the world.

Heffley is looking at his time together with Brötzmann as a whole, a three-hour

moment whose flow of words is contained in a shifting shimmer of gold and black and

white. It is not words on a page he sees but the actual time of their exchange in the world.

His eyes excise, laser-like, the opening words exchanged: three pages worth of

Brötzmann's personal and FMP history he could work into the chapter (Six) on FMP; he

leaves in the large chunk following because historical recount gave way to the inner

experience of Brötzmann's own perception of the history now, and to Heffley's, and the

conversation was dynamic and balanced—a medium making itself its messages—

touching on the idea of breath-based rather than heartbeat-based improvisation… on the

poignancy of falling in first, formative love with an "other," changing "self" forever, but

having no response to make to that love except what "self" can be and make, the thrill

and joy when that proves to be love's own response… the sense of place of Wuppertal…

the suggestion of synæsthesia in the involvement with painting (of music's flow with

vision's moment)… the economic challenges of the moment, the musical and personal

contours of its projects—of most interest, the solid, active links with African-Americans,

Africans, Japanese, after a career marked by a very public individuation from American

jazz, and by proactive, even defensive assertions of European and German identities…

the issues of composition and improvisation in which he wants to couch this look at the

players… the talk about the Wall coming down, the East-West thing (Brötzmann's

identification of himself as Prussian catches Heffley's eye immediately; this would be of

great interest in considering the nature of the relationship between the West and East

German players)… the telling observations of childhood education-socialization at work,

the contrast between (per Hall) acquired (improvisatory) and formal/technical

(performative) culture, their conflict in action… the confirmation of the music's

contemplative as well as cathartic aspects, and of its timeless value thereby to the artist as

an older man, matching or exceeding that it held for the younger.

All this Heffley blessed with his eyes, caused it to grow in its goldness. He would mix

it in with the other exchanges, make them all a delicious stew cooked slow over

Olympian fire, for all the world to sup for millennia to come.

What wouldn't go in was some twelve pages worth of gossip and chitchat, some

griping, most affectionate, all respectful, about musicians and others Brötzmann had

worked with. Maybe some of that material would work in the spoken narrative framing

the musical examples supplementing the text.

Now—what about that problem of time slipping around like an episode of Star Trek?

He supposed he could—should—attend to it for a moment or two, while there was a lull

in the Olympian action. I glanced at him, his body, far below, finishing off its meal in the

Greek restaurant, riding the rails in the air over water, a freight he could never hop in his

own land. He didn't seem to be suffering unduly from these disjunctures between "I" and

"he," between the vertical and horizontal, no-time and time, Moment and Flow; he

seemed to realize that he was messing with forces beyond his control, certainly beyond

that of his rational intellect.

Why shouldn't his rational inquiries into musical and biological time trigger his own

body's experience of linear time's chimeric evanescence? Why shouldn't his rational

inquiries into the Urgrund of Western and African history and cultural identities become

his own visits to , and his own possession by the "spirits" there?

What do you expect to come of his inquiries into the nature of consciousness as both

personal and universal, both immanent and transcendent, other than his own possession

by, out of all such spirits, ME?