Personality Traits: Fact or Fiction? A Critique of the...

Transcript of Personality Traits: Fact or Fiction? A Critique of the...

Journal of Fcnonalny and Social ftycholofy1984. Vol 47. No 3. 1028-1042

.Copymbi 1984 by theAmerican Psychological Aaocution, Inc.

Personality Traits: Fact or Fiction?A Critique of the Shweder and D'Andrade

Systematic Distortion Hypothesis

Daniel RomerUniversity of Illinois at Chicago

William ReyelleNorthwestern University

According to Shweder and D'Andrade (1979, 1980), covariation in memory-basedratings of people's behavior is determined more by semantic relations betweenbehavior categories than by actual co-occurrence. They claim therefore that theexistence of personality traits is largely a fiction supported by our conceptionsrather than by reality. Contrary to this hypothesis, we argue that semantics arelogically implicated in both the observation and recall of behavior and thatsupport for this assumption can be found if immediate encodings of behavior areas sensitively scaled as subsequent memory-based ratings. Results of a demonstrationexperiment supported this conclusion. When immediate encodings were scaledacross all behavior categories, the relation between semantics and memory wascompletely explained by the role of semantics in the immediate encoding ofbehavior. However, when immediately encoded behavior was simply identified(rather than scaled), support for systematic distortion was obtained. Previoussupport for the systematic distortion hypothesis may therefore be attributed tothe use of too simple a coding scheme for the measurement of immediatebehavior. Implications for the existence of personality traits and for personalitymeasurement are discussed.

Whether personality traits truly exist orare merely artifacts in the minds of observershas long been a controversial question (e.g.,Fiske, 1978; Mischel, 1968, 1973; Newcomb,1931; Thorndike, 1920). Of the many usesof the trait concept, perhaps the most criticalis the assumption that the numerous mani-festations of a person's behavior can be sub-sumed by underlying stabilities in characteror personality. Thus the many ways of ex-pressing aggression might be traced to theexistence of a stable characteristic or traitsuch as aggressiveness. Without this assump-

This research was supported partly by Grant No.MH29209 from the National Institute of Mental Health(William Revelle, principal investigator). We thank T.Lederer for her assistance in preparing this manuscript,and L. Hazlewood, A. Jackson, R. McLaughlin, J. Onkcn,D. Parella, B. Park, K. Rasinski, and S. Siegel forparticipating as observers. Helpful comments from L.Alloy, J. Crocker, and R. Shweder on an earlier versionof this article are gratefully acknowledged.

Requests for reprints should be sent to either DanielRomer, Department of Psychology, Box 4348, Universityof Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60680, or WilliamRevelle, Department of Psychology, Northwestern Uni-versity, Evanston, Illinois 60521.

tion, the trait concept loses much of itsscientific appeal. Writers such as Mischelhave thrown considerable doubt on the as-sumption of stable traits by appealing to thesituation specificity and plasticity of behav-ioral manifestations of traits. Others (e.g.,Bowers, 1973; Endler & Magnusson, 1976)have emphasized the importance of the in-teraction between person variables such astraits and situations. Although the issue is farfrom settled, these attacks have placed thevalidity of the trait concept somewhat inquestion.

One very strong case against the trait con-cept can be derived from research on theattributional behavior of the layperson. Awidely observed phenomenon, the funda-mental attribution error (Jones, 1979), sug-gests that the layperson overestimates thecontribution of personality characteristics ascauses of behavior and similarly ignores theeffects of situations. Thus it can be arguedthat the scientific appeal of traits actuallyreflects the layperson's tendency to overattri-bute underlying stability in others' behaviorwhen actually behavior might largely be de-

1028

PERSONALITY TRAITS: FACT OR FICTION? 1029

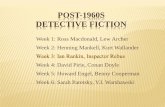

Table 1Correlations (TS) Between Immediately Observed Behavior and Between Memory for Behavior,and Semantic Similarities (&s) Between Behavior Categories

Category

ABC

Behavior

A

TAB

B C Category

abc

Memory

a

Ib

'be

C Category

a

y

Semantics

a

i0 y

termined by situations. This error might thenbe compounded by tendencies to make error-free predictions of future or related behaviorfrom small samples of behavior and to drawthese inferences on the basis of heuristicssuch as representativeness rather than carefulattention to actual behavior rates (Kahneman& Tversky, 1973).

Shweder (1975, 1977) and D'Andrade(1965, 1974) advanced one extremely pro-vocative interpretation of these attributiontendencies. According to their "systematicdistortion" position, observers impose se-mantic structure on behavior, when in factno such structure exists. That is, rather thanrecognizing the true empirical relations be-tween behavior categories, observers use arepresentativeness or similarity heuristic todescribe the relations between categories.

In support of their view that traits existonly in the minds of observers, Shweder(1975, 1977) and D'Andrade (1965, 1974)referred to the relations that obtain betweenimmediately observed behavior, subsequentratings of the same behavior and the semanticstructure of the ratings. When frequencycounts of behavioral observations (or encod-ings) are calculated for a set of individualsand those encodings are subsequently ratedfrom memory by the same observers, it ispossible to determine correlations betweenbehavior categories based on either the be-havior encodings or on the ratings. Further-more, one can determine semantic relationsbetween the various behavior categories byasking observers to report the perceived sim-ilarities between the categories. As shown inTable 1, these matrices have correspondingelements for their respective rows and col-umns, permitting the calculation of a simi-larity or correlation coefficient between ma-trices.

Shweder and D'Andrade (1979) reviewedthe results of seven studies in which therelevant comparisons were made. These stud-ies reveal that the behavior correlations aresmall and often near zero, whereas the mem-ory-based (ratings) correlations are larger.Furthermore, the rating correlations appearto parallel the semantic similarities (averager = .75) to a greater degree than the behaviorcorrelations (average r = .26). Finally, the im-mediately encoded behavior matrices correlateonly about .25 with the respective memory-based matrices.

From data such as these, Shweder andD'Andrade (1979) concluded that (a) imme-diately observed behavior counts reveal littlecohesion in the actual co-occurrence of be-havior, (b) trait ratings based on recollectionof observations contain considerable cohesionand structure that is closely related to thesemantic connections between traits; and (c)observers relying on memory-based datacommit the various attribution errors outlinedearlier and impose a semantic similaritystructure on the co-occurrence of behaviorin the observed sample. Shweder and D'An-drade noted that these conclusions do notrule out the existence of stable patterns ofindividual differences; rather, they suggestedthat the belief that these patterns are organizedinto stable traits is not only invalid but isconcocted by observers who are too overbur-dened by the data that must be rememberedto render an accurate account of the truedata pattern.

Shweder and D'Andrade (1980) did notleave the matter here, however, because it wasnot only memory burdens that were heldresponsible for inaccurate judgment of be-havior co-occurrence. As anthropologists theywere interested in the parallels between theseconclusions and variation in cultural belief

1030 DANIEL ROMER AND WILLIAM REVELLE

systems that are sometimes empirically in-valid. Just as some primitive cultures engagein what is known as magical thinking, theaverage civilized person "confuses proposi-tions about likeness with propositions aboutco-occurrence likelihood" (Shweder, 1977, p.642).' We attribute causes (e.g., traits) toevents (e.g., behavior) based on their semanticsimilarity rather than on their empirical cor-relation. Thus "the failure to report accuratelyupon correlational relationships in one's ex-perience is an indication of the absence of aconcept of correlation in normal adults"(Shweder, 1977, p. 642). We are not simplypoor tabulators of experience; we are ignorantof the basic concepts needed to draw theappropriate inferences from experience (seeCrocker, 1981, for a review).

These conclusions have not gone unchal-lenged. Block, Weiss, and Thome (1979)noted some difficulties in drawing these con-clusions from Shweder and D'Andrade's(1979) data. For example, many factors suchas the definitions of behavior can affect thecorrelations between behavior types resultingin a poor match between matrices. In thisarticle we focus on some interpretive difficul-ties that we believe are sufficiently serious tothrow great doubt on Shweder and D'An-drade's conclusions. In order to do so, webegin by setting out a model of the role thatsemantics play in the behavior-encoding pro-cess and in subsequent memory-based judg-ment.

Model of Behavior Encoding

Figure 1 outlines a structural model forthe relations between behavior encoding,memory for behavior, and semantics. Struc-tural modeling seems to be appropriate fordiscussing the relations between these pro-cesses inasmuch as the data Shweder andD'Andrade (1979) discussed are essentiallycorrelations between measures of these pro-cesses. Furthermore, the use of structuralmodeling helps to clarify both the theoreticaland measurement assumptions that enter intothe conclusions that can be drawn fromcorrelational data.

The starting point in the model is thecovariation in behavior exhibited by a set ofindividuals. The assumption here is that be-

Figure 1 Structural model showing the underlying rela-tionships between behavior, encoding, semantics andmemory. (The observed measures of these latent variablesare assumed to reflect both true and error varianceLatent variables are represented by circles, and causalrelationships by arrows.)

havior is simply a set of physical movementsor states; no label is attached to behavioruntil it is encoded by an observer. Thisassumption is a virtual truism in the socialsciences and Shweder (1977) apparently ac-cepted it. One implication of this assumptionis that covariation in behavior is by definitionunobserved and so is treated exclusively as alatent variable. Its first manifestation occursat the encoding stage. This encoding is as-sumed to be a joint function of both behaviorand the semantic structure that observers usein encoding it (Path A). To encode behaviorsuch as "giving praise," for example, requiresmapping rules between events or states (e.g.,smiling, making positive remarks, pattingsomeone on the back) and a behavior label.This is the province of semantics.

Semantics also define relations betweenbehavior labels. Thus "giving praise" is per-haps similar to "offering encouragement" but

1 Shweder (1977) gives examples of magical thinkingin the therapeutic practices of the Azande who attemptto cure epilepsy by the administration of monkey skullsor to cure ringworm by the application of fowl excrementThese "cures" are said to be conceived because of theirresemblance in some respect to the ailment.

PERSONALITY TRAITS: FACT OR FICTION? 1031

different from "giving criticism." Indeed, onemight say that the behavior-encoding processimplicitly rests on such similarity judgmentsbecause the observer must decide how con-gruent a given behavior is with all of themany labels that might be matched to itbefore he or she arrives at the appropriatedescription. Although we accomplish thisjudgment with great ease, it is by no meansunderstood how we do so, and the presentmodel contains no assumptions about thisprocess other than that it occurs. However,an implication of the model is that differentsemantic structures produce different encod-ings. Thus although the model is consistentwith Shweder and D'Andrade's (1979) as-sumption that semantics determine how wedescribe reality, there is nothing magical aboutthis process. Indeed, the effect of semanticsis purely definitional in the sense that exceptfor error in perceiving behavior,2 semanticscannot be wrong at this stage.

The memory of this encoding process ispresumably the impression that remains ofthe individuals observed (Path B). It is at thisstage that trait relations are said to be con-structed more by semantics than by trueencodings (i.e., Path C is large whereas B issmall). In addition, the apparently small sizeof B is said to be evidence for the conclusionsthat we are insensitive to the relations betweenbehavioral events and that we have difficultyextracting the true correlational structure ofour experience.

To this point we have discussed the impli-cations of the systematic distortion positionin terms of theoretical latent variables. Alsoincluded in the model, however, are the cor-responding measures of encoding (E), mem-ory (M), and semantics (S). These measuresare imperfect in the sense that each of thelatent variables is indexed by instrumentsthat are subject to error. This error has atleast two components: random noise andstable error. The former component is typi-cally thought of in terms of the reliability ofthe measuring instrument's readings and isindexed by test-retest or interitem correla-tions. Arrows between the latent variablesand their measures (e.g., rs) represent thissource of reliability.

The second component, however, reflectsthe inability of an instrument to capture the

true variable even if its reliability is perfect.In this case, the instrument's readings arepartly determined by a stable error that isuncorrelated with the true latent variable ofinterest. The result is that there is variationin the true variable that cannot be detectedby the instrument. This sort of error is usuallyconceived of as invalidity because the instru-ment will not enable one to predict a criterionas well as a more valid instrument will. Inthe absence of a more valid instrument,however, it is difficult to determine how validan instrument is, and the error can be mis-attributed to a weak relation between thelatent variable and a criterion variable. Be-cause we hope to show that this source oferror is responsible for the weak relationbetween encoding and the other variables, weinclude a case of a method factor in themeasurement of encoding. Even if the reli-ability of E is large, its relation to the trueencoding variable (rE) will be attenuated bymethod error (rME). To the degree rE is small,the relation between E and M or E and Swill also be attenuated. However, a measurethat is not subject to a method bias (E')should be a more valid indicator of encodingand hence should display higher correlationswith the other variables in the model.

Shweder and D'Andrade (1979), on theother hand, assumed that the low correlationbetween encoding and memory measures isthe result of the low value of Path B (i.e., therelation between the latent encoding andmemory variables). Second, Shweder andD'Andrade assume that the high correlationbetween M and S is produced by the directPath C rather than the indirect paths (AB)mediated by encoding. That is, rather thansemantics determining the relations betweenobserved behavior at the encoding phase,they assume that semantics "fill in" theserelations at the later reconstruction or mem-ory phase. Furthermore, because M and Sare highly correlated but neither E and S norE and M are, the conclusion seems to followthat Paths A and B are small. To be certainof this conclusion, however, we must be con-

2 Shweder and D'Andrade seem to believe that ongoingbehavior can be accurately encoded, so error in perceivingbehavior is not relevant to their hypothesis.

1032 DANIEL ROMER AND WILLIAM REVELLE

vinccd that encoding is measured as validlyas the other variables.

Measurement of Behavior Encoding

The measurement of ongoing behaviorusually involves a set of behavior categories,a sampling scheme for observing behaviorand a coding scheme for recording the be-havior that occurs (cf. Altmann, 1974; Sack-ett, 1978). Because the major function ofbehavioral observation is to determine behav-ior rates, the recording scheme that is usuallyused is an identification code with which anobserver assigns a score of one to the mostsalient behavior categories observed in anyperiod and a score of zero to all other cate-gories. Frequency counts for each behaviorare then obtained by summing the ones andzeroes over observations. Shweder and D'An-drade (1979) recommended the use of thiscoding because of its simplicity and facevalidity: "for recording the actual behaviorof the subjects . . . count frequencies ofdifferent kinds of behavior. . . using a simplecoding scheme" (D'Andrade, 1974, p. 162).

Such simple coding schemes can be con-trasted with more differentiated codes thatare seldom used in observation research. Theideal procedure would involve a set of ob-servers, each of whom observes only onebehavior category for each subject of obser-vation. Although each observer would monitorthe same situation (either in person or fromvideo recordings), a continuous record of thesubject's behavior would be recorded on ascale ranging from a high to a low degree ofthe behavior in question (perhaps with a penthat traces the observer's judgment on a rollof steadily moving paper). This record wouldthen be independent of the semantic biasesof other observers. In addition, the continuousrecords could be averaged to obtain rateinformation or they could be correlated withthe records of other categories to determinehow categories covary. Although this proce-dure is not only ideal but perhaps Utopian,there is one aspect that can easily be adaptedfor use in research, namely, the scaling ofobservations along each of the categories inthe behavior inventory.

To compare scaling over all categories withidentification coding, we consider a simple

DOMINANT

ARROGANT

COLD

INTROVERTED

EXTRAVERTED

WARM

UNASSUMING

SUBMISSIVE

Figure 2 Wiggins's circumplex model of interpersonaltrait terms.

two-dimensional category system that hasbeen studied by several researchers (e.g.,D'Andrade, 1965; Leary, 1957). Accordingto a recent analysis by Wiggins (1979), thesame dimensions (dominance-submission andwarmth-coldness) form a circumplex struc-ture underlying a wide assortment of inter-personal traits. As shown in Figure 2, eightof these traits are defined by the four polesof the trait dimensions and by the four loca-tions intermediate to these poles. Correlationsbetween all possible pairs of these categoriesare shown in Table 2. These correlationsindicate that neighboring categories are highlycorrelated (r = .71). For example, althoughdominance and extraversion are distinguish-able behaviors, they are both semanticallyrelated to the underlying dominance dimen-sion. Thus behavior categories may have con-siderable semantic overlap even though theyare descriptive of different ranges of behavior.

When any of the categories in the systemis observed in behavior, it can be uniquelyidentified by using a simple recording scheme.Nevertheless, the use of identification codingobscures the implicit semantic relations be-tween the categories. As an example, identi-fication codings for the eight categories areshown in Table 3. Each category is observedonce and the corresponding frequency countis recorded (as one for the observed behaviorand zero for the rest). The correlation matrixbetween these observations for four categoriesis also shown in the table. The values areuniformly negative and would approach zero

PERSONALITY TRAITS: FACT OR FICTION? 1033

Table 2Correlation Coefficients Between Traits in Wiggins's Circumflex Model of Trait Terms

Trait

1. Dominant2 Arrogant3. Cold4 Introverted5. Submissive6 Unassuming7. Warm8. Extroverted

1

__

.71

.00-.71

-1.00-.71

.00

.71

2

—.71.00

-.71-1.00

-.71.00

3

—.71.00

-.71-1.00-.71

4

.71

.00-.71

-1.00

5

.71

.00-.71

6

—.71.00

7

.71

8

—

as the number of categories in the codingsystem was increased.

The corresponding codes that might beobtained if we used scaling over all categoriesis also shown in the table. Using a 5-pointscale, we assign a value of 2 to the categorymost descriptive of the behavior, a value of 1to the categories closest on the circumplex,and so on down to - 2 . When these scalingsare correlated between the categories, a matrix(shown in the table) that is reflective of thecircumplex structure results. Comparing thesemantically veridical correlations with theones obtained from identification coding, wesee that identification coding underestimatesrelations between semantically similar cate-gories and overestimates relations betweensemantically dissimilar categories.

The bias introduced by identification cod-ing does not disappear merely as a result ofaggregation over repeated observations of thesame individuals. To the extent that individ-uals show stability in their behavior, the biaswe describe will remain. At the other extreme,if individuals exhibited no stability, the biaswould disappear. The most likely empiricalconsequence of aggregation, however, is thecancellation of measurement error and theincreased ability to observe stability in indi-vidual behavior (Epstein, 1979). Thus to theextent individuals show any stability in theirbehavior, aggregation over observations wouldbe expected to increase the reliability offrequency counts and hence to maintainrather than to diminish the bias.

Block et al. (1979) noted that "the use offrequency counts of behavior is not a sufficientmeans of operationalizing complex psycho-logical concepts" (p. 1062). However, theydid not pursue the implications of identifi-

cation coding for determining the relationsbetween behavior categories. In responseShweder and D'Andrade (1979) stated thatthe criticism

is true but beside the point. This criticism would beappropriate were we trying to develop a personalityassessment instrument Our main concern in these studiesis not to develop personality assessment techniques butto test hypotheses about systematic distortion in memory.In trying to anchor one set of ratings in what can beobserved and counted, we have used studies that usedrelatively simple and direct methods. If we did not havesimple and direct measures, how could we know whethermemory distortion occurred? (p. 1079)

Our point is that identification coding doesnot allow the true semantic relations betweenbehavior categories to emerge even if theyare reliably exhibited in behavior. In conse-quence, the evidence for systematic distortionmay be entirely attributable to the use ofidentification coding in the recording of ob-servations and the use of scaling over allcategories in subsequent memory-based rat-ings. Because the examples presented in Table3 involve errorless data, they do not providea sufficient demonstration of the distortionthat may be obtained with real data. Thereare several ways in which to show the effectof this distortion. One would be to simulatethe behavior of raters (using Monte Carlotechniques) and to observe the effect of erroron the results of the two coding systems.Another would be to compare the results ofthe two coding systems with two differentsets of raters observing the same set of actors.

Because we are more concerned with thepotential distortion that is due to identifica-tion coding than we are with the issue ofwhat behaviors are observed or what traitsare inferred from observations of behavior,

1034 DANIEL ROMER AND WILLIAM REVELLE

£8 8

!

go

i

a

en g

6

&

•g

I

•7 7r i r

— O — CN — O — CNI I I

O — CN — O — CN —I I I

— CN— O — CN — OI I I

CN — O — CN — O —I I I

— O — CN— O — CNI I I

— (N — O — CN —! I I

— CN— O — CN — OI I I

CN — O — CNCNO —

OOOOOOO—

oooooo — o

ooooo — oo

oooo — ooo

ooo — oooo

oo — ooooo

o — oooooo

— ooooooo

ISi

we presented observers with hypothetical ac-tors whose behavior was constrained to reflectone behavior category per situation. Becauseof the conceptual nature of this demonstrationwe collected data from only four judges ineach of our two conditions. To approximatethe effects of aggregation, we further con-strained each actor's behavior to reflect ahigh degree of trait stability across situations.A comparison between the two coding con-ditions permits us to demonstrate that iden-tification coding produces the typical patternof systematic distortion but that scaling overall categories retains the semantic relationsbetween categories at both the encoding andmemory phases of judgment.

Method

In this experiment, observers judged instances of be-havior either by identifying the best description or byscaling the instances across all categories. Wiggins's (1979)circumplex model of interpersonal trait terms was usedto define an inventory of eight behavior categoriesD'Andrade (1965) analyzed a similar circumplex in thisfirst statement of the systematic distortion hypothesis.Four examples of each behavior category were selectedfrom Wiggins's final set of adjective scales. Each set offour examples was arbitrarily assigned to one of eighthypothetical actors. For example, instances of "dominant"are self-confident, domineering, assertive, and firm. Weconverted each adjective into an observation by describingan instance of an actor's behavior, using the adjective.For example, in the sentence "Rick was self-confident atthe meeting," self-confident is an observation of Rick. Allobservations were similarly worded in that an actor (e.g.,Rick) was seen doing something (e.g., being self-confident)in a certain situation (e.g., at the meeting). The fourreplications of each of the eight circumplex poles resultedin 32 observations.

Procedure

The observers' task was (a) to form an impression ofeach of the eight actors, (b) to record the 32 observationsusing one of two coding schemes, and (c) to rate frommemory each of the actors on each of the eight circumplextraits. Observers were told that they would be given briefdescriptions of behavior of eight different people. Theirtask was to try to form an impression of what eachperson was like. Furthermore, they were asked to rateeach description. In the identification condition, theirrating was to be made by indicating which of the eightcircumplex traits best described each behavior. In thescaling condition, they were asked to rate each descriptionalong each of the eight circumplex traits. They made theratings using an equal-interval scale ranging from 1 (notat all) to 7 (very much).

Preliminary testing revealed that the memory task wasdifficult for our observers. To facilitate recall of the actors'

PERSONALITY TRAITS: FACT OR FICTION? 1035

Table 4Results of Experiment for Each Observer

Observer a

Identification conditionABCD

M

.93

.84

.82

.79

.85Scaling condition

EFGH

M

.95

.95

.91

.81

.91

Immediatecoding

andmemoryrating'

.66

.30

.65

.40

.50

.82

.95

.11

.36

.56

Correlations between

Immediate andmemorymatrices'

r

.31

.43

.53

.52

.45

.99

.99

.92

.74

.91

3

r*

.26

.22

.58

.57

.41

.98

.96

.86

.72

.88

Immediate andsemanticsmatrices

r

.19

.43

.49

.49

.40

.73

.71

.76

.65

.71

b

rs

.27

.33

.49

.48

.39

.72

.74

.79

.74

.75

Memory and

r

.74

.73

.67

.53

.67

.74

.73

.62

.43

.63

semanticsmatrices1"

rs

.79

.74

.69

.57

.70

.70

.73

.73

.45

.65

Note Correlations between immediate, memory and semantics matrices are reported with Pearson (r) and Spearman(rs) coefficients,•tf = 64. "#=28 .

behavior, observers were first asked to learn the eightactors' names.3 When subjects could recall all the names,the experiment began. Behavior descriptions were pre-sented on a small television monitor controlled by anApple II computer. The computer was programmed torandomly assign each of the actors to one of the eightpoles of the circumplex. It was also programmed to orderthe 32 behavior descriptions in a block random order.Observers responded by typing their answers directly intothe computer terminal, and so no record of their judg-ments was available to them. Observers could take aslong as needed to inspect each behavior descriptionbefore indicating their response.

Immediately following the encoding phase of the ex-periment, observers were asked to rate each actor oneach of the circumplex traits. The order for rating theactors and traits was random across subjects. For example,the actor was presented in the question, "Howwas Rick?" in which the blank was filled with one of theeight traits. Observers could take as long as needed torespond before the next rating was requested. They againrecorded their ratings by typing a number between 1 and7 into the terminal.

SubjectsEight graduate psychology students volunteered to

participate in the study. They were randomly assigned toeither of the coding conditions with four in each. Theywere unaware of the purpose and issues of the researchat the outset

Results

During the encoding phase of the experi-ment, observers were shown each actor four

times. This procedure allowed us to estimatethe reliabilities of the respective codingschemes. To do this, we calculated coefficientalpha for each behavior category for eachobserver.4 Because these coefficients wereuniformly high for all eight categories, wereport each observer's average a for the eightcategories. As shown in Table 4, the reliabil-ities were equally high for both schemes.Thus any differences between these codingsare unlikely to be attributable to the consis-tency of responses with each coding instru-ment. Because these reliabilities were high,we summed each observer's judgments overthe four replications to obtain a single Tar-get X Behavior (8 X 8) encoding matrix.

To determine how well observers' memory-based impressions matched their immediateencodings, we calculated the correlation be-tween their encoding scores and their mem-

3 The names we selected for the eight targets wereDon, Doug, Fred, Jack, Jerry, Rick, Roy, and Walter.

4 We found a by treating the four blocks of observationsas analogous to four items, and the eight actors asanalogous to individuals responding to these items. Thatis, a is an estimate of the generalizability of between-actor differences based on the variation between actorswithin blocks and the variation within actors acrossblocks.

1036 DANIEL ROMER AND WILLIAM REVELLE

ory-based ratings. These correlations indicatethat observers forgot some of their immediateimpressions between the two parts of theexperiment (Table 4). Indeed, one observer's(G's) correlation, r(62) = .11, failed to reachsignificance. Such forgetting is necessary forsystematic distortion to appear. Thus ourexperimental analog of behavioral observationsatisfies the requirements for the typical dem-onstration of systematic distortion.

Examination of the (Pearson and Spear-man) correlations between the semanticstructure matrix (i.e., the theoretical circum-plex pattern in Table 2) and the matrices ofPearson correlations between behavior cate-gories for both phases of the experimentenables us to determine the role of semanticsin judgment. As shown in Table 4, the rela-tions among semantics, encoding, and mem-ory depended on the coding scheme. Theidentification condition replicated the typicalsystematic distortion pattern. The semanticand memory matrices were more highly cor-related (average r = .67) than the semanticand encoding matrices (average r = .40). Thussemantics were more closely related to mem-ory ratings than to encodings, and the latterwere only moderately related to memoryratings (average r - .45). Spearman coeffi-cients yielded the same results.

In the scaling condition, however, we foundthat the semantic matrices were no morehighly related to the memory matrices (av-erage r - .63) than to the encoding matrices(average r = .71). Indeed, the relations be-tween semantics and encoding were slightlylarger than between semantics and memory.Also, we saw that the relations between be-havior categories at the encoding and memoryphases were quite similar (average r = .91),so that little changed in the relations betweencategories in the two phases of the experiment.It appears therefore that the typical systematicdistortion pattern does not obtain when scal-ing is used to record observations.

The most interesting comparison, however,was the one revealing the striking differencebetween the identification and scaling condi-tions for the relations between immediateand semantic matrices. In the identificationcondition, the immediate-semantic correla-tions ranged from .19 to .49, whereas in thescaling condition they ranged from .65 to .76.

This suggests that semantics are highly relatedto immediate encodings of behavior, but onlywhen the appropriate measurement is taken.

In Table 5 we illustrate some of the differ-ences between the results of the two codingsystems (behavior correlations for observersA and E)5 and we illustrate how the patternspredicted earlier (Table 3) were obtained. Inthe identification condition (Observer A),Pearson correlations between behavior cate-gories in the immediate encodings tended tobe negative and near zero. The average ab-solute correlation was only .17. The averageabsolute correlation for A's memory-basedratings was much larger (.63), which couldsuggest that systematic distortion has oc-curred. That this was a consequence of thecoding scheme rather than biases in recall,however, is seen in the results of the scalingcondition (Observer E). E's average absolutecorrelations between behavior categories werelarge and similar at both encoding (.63) andmemory (.59) stages. Furthermore, the indi-vidual correlations were more evenly balancedbetween positive and negative scores. Thereis thus evidence for systematic distortion onlywhen the observer's ratings are limited by theuse of identification coding. When ratings areused in both the encoding and memory phasesof the experiment, the typical systematic dis-tortion pattern disappears.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to dem-onstrate the importance of coding schemesfor recording the frequency of observed be-havior. We argued that frequency counts ofsimple behavior identifications introduce amethod bias that attenuates the validity ofbehavior observations. As a result, the abso-lute magnitudes of correlations between be-havior categories are attenuated.

Memory-based ratings of behavior fre-quencies, however, are typically scaled acrossall behavior categories. These ratings tend tocorrelate with observed frequencies, but theyalso tend to correlate more strongly betweenbehavior categories than frequencies obtainedfrom simple identification coding. These phe-

!Data for the remaining observers were similar andso were not included in the table.

Table 5Intercorrelations

Behavior

Between Behavior Categories for TWo Observers

Observer A (Identification)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3

Observer E (Scaling)

4 5 6 7 8

Immediate codings1. Dominant

2. Arrogant

3. Cold

4. Introverted

5. Submissive

6. Unassuming

7. Warm

8. Extroverted

Memory Ratings

1. Dominant

2. Arrogant

3. Cold

4. Introverted

5. Submissive

6. Unassuming

7. Warm

8. Extraverted

—- .18

.10- .18

-.18

-.18

- .23

-.24

—.86.63

- .89-.91

-.91

-.54

.65

—- .15

-.15

-.15

-.15

- .18

.18

—.66

- .70

- .79

-.91

-.71

.54

—-.15

-.15

-.15

-.18

-.19

—- .40

-.55

- .53

-.80

.03

—- .15

-.15

-.18

- .19

—.79.81.19

- .87

—- .15

-.18

-.19

—.71.41

- .65

—-.18

-.19

—.53

- .65

.04 —

.13 —

.86

.10

.96

.96

.93

.07

.91

.90

.32

.88

.88

.86

.01

.91

—.46

- .76

- .73

- .69

- .30

.70

.51- .78

- .78- .74

-.31

.70

.17

.19

.26- .98

- .26

—.04.04.11

- .82

-.05

—.99.98

- .34

- .99

—.99.96

- .34

-.88

—

.99- .36

- .98

—.96

- .34

- .88

—- .44

-.97

—- .34

- .93

.40

.26

oJ

1038 DANIEL ROMER AND WILLIAM REVELLE

nomena were replicated in the present exper-iment. Ever since Newcomb (1931) first notedthese facts, researchers have questioned thevalidity of behavior ratings. Shweder andD'Andrade (1979) formulated this skepticismin terms of a systematic distortion that isintroduced by observers' reliance on semanticrelations between behavior categories ratherthan their actual co-occurrence. Our point isthat it is the validity of behavior coding thatis in question and that the true interbehaviorrelations are more validly measured withratings.

Thus in the present experiment, relationsbetween immediate ratings of behavior cor-related highly with relations between memory-based ratings (r = .91). When identificationwas used to measure encoding, however, therelations between behavior categories did notcorrelate as highly with relations betweenmemory-based ratings (r = .45). These resultsindicate that it may not be anything peculiarto memory-based ratings that introducesstronger correlations between behavior cate-gories; rather, it is the use of ratings per sethat is responsible, whether they are con-ducted immediately or from memory. ThusShweder and D'Andrade's (1979) point thatsemantic relations predict memory relationsbetter than immediate encoding relations mayalso be a function of coding method. Wereplicated the systematic distortion in mem-ory phenomenon with identification coding;however, the phenomenon disappeared whenobservations were scaled across categories atboth encoding and memory phases. Indeed,semantic relations predicted immediate en-codings slightly better than they predictedmemory relations.

Whereas Shweder and D'Andrade (1979)interpreted the correlation between semanticsand memory as causal (Path C in Figure 1),the present results with ratings suggest analternate hypothesis. According to our model,the relation between semantics and memorycan be completely predicted by the effect thatsemantics have on encoding (Path A) and theeffect of encoding on memory (Path B). Wewould expect the correlation between seman-tics and memory to be equal to the productof our estimates of Paths A and B (.71 and.91). From our results, this product (.65)agrees well with the obtained correlation

Table 6Intercorrelation Matrices Derived FromImmediate Encodings of Behavior (UpperTriangle) and Subsequent Ratings (LowerTriangle) in Newcomb's (1931) Study

Behavior

1.2.3.4.5.

1

_

.67

.61

.97

.66

2

.52—.68.88.92

3

.05

.03—.66.77

4

.29- .14-.11—.75

5

.20

.08

.48

.16—

Note. Behavior categories are as follows: 1. Tells of hisown past, and of the exploits he has accomplished. 2. Givesloud and spontaneous expressions of delight or disapproval.3. Goes beyond only asking and answering necessary ques-tions in conversations with counselors. 4. How is the quiethour spent? 5. Spends a lot of time talking at the table.Data are based on observations of 30 boys at a summercamp.

(.63). Thus the present results are consistentwith the hypothesis that the correlation be-tween semantics and memory is entirely spu-rious (i.e., C = 0) in that the correlation isthe result of semantics at the encoding phase,an effect that is simply registered again inthe memory phase. When identification cod-ing is used, however, these conclusions donot follow. But the higher correlation betweensemantics and memory is shown to be theresult of the fact that both of these processesare measured with ratings. Identification cod-ings do not correlate as highly with either ofthese ratings as the ratings correlate witheach other.

A subset of Newcomb's (1931) data, takenfrom Shweder (1979), illustrates the problemsproduced by identification coding. New-comb's observers recorded various instancesof behavior reflecting extraversion-introver-sion among their summer-camp subjects. Onlyone behavior category was recorded at a time.In Table 6 we show the correlations betweenfive of these categories as obtained fromobservations and subsequent ratings (on a5-point scale for each category). As is evident,many of the observed behavior correlationsare near zero or negative. The ratings corre-lations are much higher. Although only oneof the categories might describe a given ob-servation, they are all conceptually related.These relations cannot appear as stronglywhen identification coding is used as when

PERSONALITY TRAITS: FACT OR FICTION? 1039

Table 7Tau Coefficients Between Behavior Categories Derived From Immediate (Upper Triangle) andMemory-Based Ratings (Lower Triangle) in Shweder and D'Andrade (1980)

Category

1. Agree2. Comply3. Praise

4. Advise5. Inform6. Suggest

7. Question8. Criticize9. Disagree

10 Joke11. Ridicule

1

_

.28

.29

.07

.11

.06

-.01-.31-.42

.16- .24

2

-.67—39

.07

.11

.12

-.11-.31-.18

-.25-.50

3

.00

.33—

.08-.05

.03

- .06-.46-.31

.21-.27

4

.33-.67-.67

.42

.51

.24

.10

.05

-.33-.03

5

.00-.33

.33

.00

.37

.14

.00-.10

-.21-.24

6

-.67.33

-.33

00-.33—

.11

.13-.02

-.49-.29

7

-.67-.33

.33

.00

.33

.33

_.12

-.01

-.19-.13

8

.00-.33

-1.00

.67-.33

.33

-33_

.59

-.30.39

9

1.00-.67

.00

.33

.00-.67

-.67.00

—

-.11.45

10

' .00.33.33

-.67-.33- .33

-.33- .33

.00

—.17

11

.33

.00-.67

.33-.67

.00

-.67.67.33

.00—

Note Numbers in italics represent correlations between categories that are semantically similar

ratings are used. Thus Newcomb's conclusionthat the ratings contain semantic biases maynot be an appropriate interpretation.

In a more recent study by Shweder andD'Andrade (1980), three observers identifiedinstances of interpersonal behavior amongfour videotaped family members. The cate-gories were examples of normal kinds ofverbal behavior (e.g., agree, comply, praise).The resulting matrices of T coefficients forencoding and memory are shown in Table 7.Many of the 55 T coefficients (23) they re-ported for encoding relations among 11 ofthese categories were less than —.30. Thecorresponding coefficients for memory-basedratings (on a 1-7 scale) contained only 9categories that were less than or equal to-.30. The difference between matrices in theoccurrence of extreme negative values is sig-nificant (z = 3.84, p < .05).

One interesting aspect of this study is thatShweder and D'Andrade (1980) did not re-strict their observers' encoding responses toonly one category in the behavior inventory.Thus the bias produced by uniquely identi-fying behavior by a single category may havebeen attenuated. Nevertheless, we do notknow how carefully observers were instructedto use all categories that are semanticallyrelated to an actor's behavior. It is clearly notnecessary to use all relevant categories toaccurately describe behavior. However, if ob-servers actually used all the categories that

were semantically related to an observation,we would expect semantically similar cate-gories to be positively correlated. That thiswas not the case can be seen by inspectingthe correlations between categories that aresemantically similar. These correlations arearrayed in italics along the diagonal of thematrices. The average T correlation betweenthese categories in the encoding matrix is- . 17, whereas the corresponding value in thememory matrix is .31. These averages aresignificantly different, t(9) = 24.0, p < .05.For example, the correlation between encod-ings of advise and suggest is .00, whereas thecorrelation based on memory ratings is .51.If observers used only one of these semanti-cally related categories at a time to describeeither form of behavior, the low correlationmight obtain. Ratings, however, might reflectthe high degree of semantic overlap in thesecategories. It appears, therefore, that the biasproduced by identification coding may havecontributed to the poor match they obtainedbetween encoding and memory matrices (r =.22). Thus their interpretation that ratingscontained semantic biases may also not beappropriate.

Researchers (e.g., D'Andrade, 1965; Shwe-der, 1975) have found that semantic relationsbetween items in personality questionnairesalso are predictive of the obtained correlationsbetween the items when they are used inpersonality assessment. There are at least two

1040 DANIEL ROMER AND WILLIAM REVELLE

ways to interpret this finding. One advancedby Shweder and D'Andrade (1979, 1980) isthat these correlations are illusory in that theactual behavior of the measured individualsdoes not contain the obtained structure. In-stead, the ratings are said to be biased byinferred semantic relations between items orby what some writers have termed an implicitpersonality theory (Bruner & Tagiuri, 1954;Schneider, 1973).

Another interpretation is that this relationdemonstrates the validity of the personalitytest. Because raters are using the items in asemantically consistent manner, their scoresdisplay internal consistency. Physical scientistswho measured the two sides of various rect-angles would expect these ratings to be or-thogonal if sufficient variation in the variableswere observed. This structure would be im-plied by the semantic independence of theseconcepts. If such independence were not ob-tained, something would be considered amissin the scientists' instruments. If the scientistsalso found this pattern in their memory fortheir observations, they would be encouragedthat their memories displayed consistency.Whether their memories of specific lengthsand widths were accurate would, of course,be another question.

We think that the present results supportthis interpretation. According to our modelof behavior encoding, semantics define therelations between events (e.g., behavior) andbehavior categories. Because any behaviorhas a complete set of semantic relations withevery category, semantics partly define thestructure of items in personality tests. Thepresent results indicate that semantics cancorrelate as highly with immediate observa-tions as with memory-based impressions andthat the ability to recover these relations atthe memory phase is entirely explained bythe role that semantics play at the encodingstage. Furthermore, these findings appear tobe independent of the accuracy of the observ-er's memory. Therefore, to the extent thatscales are used correctly, one should expectsemantics to partly recover the empiricalrelations between scales.

The latter conclusion rests, however, onthe assumption that individuals differ in stableways on some observable dimensions. Theexistence of individual differences has not

been questioned by Shweder and D'Andrade(1979, 1980). Furthermore, skepticism aboutthis issue seems to be answered in part byEpstein's (1979) findings that behavioral sta-bility is available for observation if enoughsamples of behavior are measured. Thus theassumption that individual differences exist(e.g., some people are more friendly thanothers) seems to imply that trait relationswill follow semantics (friendly individualswill tend to be less hostile).

This conclusion is relevant to one of theearliest reports of evidence for systematicdistortion (Newcomb, 1931). In that study,Newcomb found that behavior ratings corre-lated significantly (average r= .41) with ob-served behavior frequencies (that were iden-tification coded). What puzzled Newcombwas that the interobserver reliabilities of theratings were as high for behavior categories(.64) that were observed by only one or noneof the raters (e.g., making one's bed) as forcategories (.71) that were observed by many(e.g., lying around):

Behaviors never recorded, never seen, and those felt tobe highly uncertain were as uniformly rated as those atthe opposite extremes. Since the guessed ratings are ofhighly questionable validity, must not the others, whichare no more uniform, be almost equally invalid? (p. 289)

An alternative explanation rejected byNewcomb (1931) is that observers used in-stances of observed behavior to infer thebehavior of subjects in unobserved contexts.If people do exhibit some stability in theirbehavior and they differ in personality, thenpredictions to unseen but conceptually relatedbehavior would seem to be a rational proce-dure (cf. Ajzen, 1977). In the absence of data(which Newcomb did not provide), we cannotsay whether such predictions are valid. How-ever, the present analysis and results suggestthat the presence of prediction to unobservedbehavior does not imply that the ratings ofactually observed behavior are invalid.

It may seem to some readers that thesemantic interpretation of behavior ratingswe present here logically implies the existenceof traits insofar as individuals differ in somepersonality dimension. However, most re-ported observations of behavior have beenconducted over only a limited set of situations.As Shweder and D'Andrade (1979) note, the

PERSONALITY TRAITS: FACT OR FICTION? 1041

trait concept also implies cross-situationalconsistency. Mischel (1973) makes this crite-rion a major focus of his critique. His pointis that such consistency is limited. Thus evenif traits seem to be an inevitable outcome ofindividual differences, the possibility remainsthat such consistencies are eliminated whenindividuals are observed across different sit-uations.

If this is indeed the case, then we wouldneed models of personality functioning thatcould predict why people behave differentlyacross situtions. Such models would presum-ably specify how individual characteristics(traits?) interact with situations. Note, how-ever, that this type of theorizing still requiresthe postulation of stable individual charac-teristics that can function as terms in theperson-situation interaction. Examples of thistype of theorizing are evident in the work ofAtkinson (1957, 1964, 1978) in the domainof achievement motivation and of Eysenck(1967, 1976, 1981) in the domain of intro-version-extraversion. A further example maybe found in the studies by Revelle and hisassociates (Humphreys, Revelle, Simon, &Gilliland, 1980; Revelle, Amaral, & Turriff,1976; Revelle, Humphreys, Simon, & Gilli-land, 1980), who have shown that the person-ality trait of impulsivity has systematic, al-though complex relationships to cognitiveperformance. These models attempt to ex-plain behavior as a joint function of bothstable individual characteristics and situa-tional variables that are denned in a theoret-ical model of sufficient complexity to makepredictions across situations and individuals.This interaction approach would seem to beprofitable for understanding personality.

Although the present experiment only ap-proximates what we regard as an ideal obser-vation procedure, it does show that use ofratings at the encoding phase is a criticalfactor in estimating the true relations betweenimmediately observed behavior categories.Our use of behavior descriptions rather thanactual physical events was a helpful shortcutfor demonstrating this point. If we had pre-sented the actual behavior of our actors, theencodings our observers would draw mighthave lower reliability, but this would be littlereason to expect this factor to differentiallyaffect the reliability of the two coding schemes.

Indeed, the reliabilities we obtained for theseschemes were equally high, a finding thatsupports our contention that it is not reli-ability of these codes but rather their validitythat does or does not produce support forsystematic distortion.

Our purpose in presenting this research isnot to argue that distortion never occurs.There are several findings that show someevidence of bias in observer reports (e.g.,Berman & Kenny, 1977; Hamilton & Rose,1980). Although these findings may lack ex-ternal validity (Block, 1977), our point is thatsuch distortions are not necessarily so largethat valid assessments cannot be obtained.Furthermore, we feel that distortion is possibleat any stage in the observation and recall ofbehavior and is not necessarily confined tomemory-based ratings. Shweder and D'An-drade (1979, 1980) argued that immediateencodings have validity that no other methodspossess. Distortion at the encoding stage hasbeen observed, however (cf. Pettigrew, 1979),and there are often theoretical reasons forexpecting such distortion (e.g., in intergroupconflict and race relations). Because behaviortakes its meaning only by virtue of its encod-ing, disagreement about its meaning wouldseem inevitable. Nevertheless, methods areavailable for reducing such errors with suchsimple devices as averaging over observers(Kenny & Berman, 1980).

What we feel is unjustified, however, is theconclusion that observers cannot draw cor-relational inferences from their experience.Neither the present research nor any we areaware of justifies this conclusion. Future re-searchers of encoding and memory of behav-ior should perhaps focus on how both objec-tive characteristics of behavior and the cog-nitive-motivational processes of observerscombine to yield the encodings we commonlyproduce. Our analysis and results suggest thatsuch models should emphasize semantics asa critical mediator in this process.

References

Ajzen, I. (1977). Intuitive theories of events and theeffects of base-rate information on prediction. Journalof Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 303-314.

Altmann, J. (1974). Observational study of behaviorSampling methods. Behavior, 69. 227-267.

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of

1042 DANIEL ROMER AND WILLIAM REVELLE

nsk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64. 359-372.

Atkinson, J. W. (1964). An introduction to motivationNew York: Van Nostrand.

Atkinson, J. W. (1978). Strength of motivation andefficiency of performance. In J. W Atkinson & J.Raynor (Eds.), Personality, motivation and achievement(pp. 117-142). Washington, DC Hemisphere

Berman, J S., & Kenny, D. A. (1977). Correlationalbias: Not gone and not to be forgotten. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 35, 882-887.

Block, J. (1977). Correlational bias in observer ratings:Another perspective on the Berman and Kenny study.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 873-880

Block, J.. Weiss, D. S., & Thome, A (1979). Howrelevant is a semantic similarity interpretation of per-sonality ratings? Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 37, 1055-1074.

Bowers, K. S. (1973). Situationism in psychology: Ananalysis and critique. Psychological Review: 80. 307-336.

Bruner, J. S.. & Tagiun, R. (1954). The perception ofpeople In G. Lindsey (Ed.), Handbook of social psy-chology (Vol. 2, pp. 634-654). Cambridge, MA: Ad-dison-Wesley.

Crocker, J. (1981). Judgment of covariation by socialperceivers. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 272-292

D'Andrade, R. G. (1965) Trait psychology and compo-nential analysis. American Anthropologist, 67. 215-228

D'Andrade, R G. (1974). Memory and the assessmentof behavior. In T. Blalock (Ed.), Measurement in thesocial sciences (pp. 159-186). Chicago. Aldine-Ath-erton.

Endler, N. S., & Magnusson, D. (1976) Interactionalpsychology and personality Washington, DC: Hemi-sphere.

Epstein, S. (1979). The stability of behavior. I Onpredicting most of the people much of the time.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1097-1126.

Eysenck, H. J. (1967). The biological basis of personalitySpringfield, 1L: Charles C Thomas.

Eysenck, H. J. (1976). The measurement of personalityBaltimore, MD: University Park Press.

Eysenck, H. J. (Ed.) (1981). A model for personalityNew York: Springer-Verlag.

Fiske, D. (1978). Strategies for personality research Theobservation versus interpretation of behavior. San Fran-cisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hamilton, D. L., & Rose, T. L. (1980). Illusory correlationand the maintenance of stereotypic beliefs. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology. 39, 832-845.

Humphreys, M. S., Revelle, R., Simon, L., & Gilliland,K. (1980). Individual differences in diumal rhythmsand multiple activation states: A reply to M. W.Eysenck and Folkard Journal of Experimental Psy-chology: General, 109, 42-48.

Jones, E. E. (1979). The rocky road from acts to dispo-sitions. American Psychologist, 34, 107-117.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1973) On the psychologyof prediction Psychological Review, 80. 237'-251.

Kenny, D. A., & Berman, J. S. (1980). Statistical ap-proaches to correction for correlational bias. Psycho-logical Bulletin, 88, 288-295.

Leary, T. (1957). Interpersonal diagnosis of personality—A functional theory and methodology for personalityevaluation New York: Ronald Press.

Mischel, W. (1968). Personality and assessment NewYork: Wiley.

Mischel, W. (1973). Toward a cognitive social learningreconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review80. 252-283.

Newcomb, T. (1931). An experiment designed to test thevalidity of a rating technique Journal of EducationPsychology, 22, 279-289.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1979). The ultimate attribution errorExtending Allport's cognitive analysis of prejudicePersonality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 5. 461-476.

Revelle, W., Amaral, P., & Turriff, S. (1976). Introversion/extraversion, time stress, and caffeine: The effect onverbal performance. Science, 192. 149-150.

Revelle, W, Humphreys, M. S., Simon, L., & Gilliland,K. (1980). The interactive effect of personality, timeof day, and caffeine: A test of the arousal modelJournal of Experimental Psychology General, 109, 1-31.

Sackett, G P. (1978) Observing behavior (Vol 2) Bal-timore, MD: University Park Press.

Schneider, D. J. (1973). Implicit personality theory: Areview Psychological Bulletin, 79, 294-309.

Shweder, R. A. (1975). How relevant is an individualdifference theory of personality? Journal of Personality.43, 455-484.

Shwwjer, R. A. (1977). Likeness and likelihood in everydaythought: Magical thinking in judgments about person-ality. Current Anthropology, 18, 637-658.

Shweder, R. A. (1979). Rethinking culture and personalitytheory, Part I: A critical examination of two classicalpostulates. Ethos, 7. 255-278.

Shweder, R. A., & D'Andrade, R. G. (1979). Accuratereflection or systematic distortion? A reply to Block,Weiss, and Thome. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 37. 1075-1084.

Shweder, R A., & D'Andrade, R. G. (1980). The system-atic distortion hypothesis. In R. Shweder (Ed.), Newdirections for methodology of social and behavior science(Vol. 4, pp. 37-58). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Thorndike, E. L. (1920). A constant error in psychologicalratings. Journal of Applied Psychology. 4, 25-29.

Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of traitterms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology. 37, 395-412.

Received February 28, 1983Revision received June 27, 1983 •