“People & Places Reading Group: experts, politicians, labs ... · late 20th-century...

Transcript of “People & Places Reading Group: experts, politicians, labs ... · late 20th-century...

“People & Places Reading Group: experts, politicians, labs and media in

late 20th-century palaeoanthropological knowledge production”

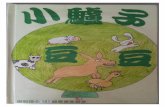

'A scientific revolution or a common and ordinary horse?': The Orce Man and the

role of experts, politicians and media during 27 years of public controversy

Miquel Carandell Baruzzi

This paper is an adaptation for this reading group of my work-in-progress

PhD dissertation. I aim that it can be an introduction to the Orce Man story

and to the questions that my approach to it has raised that I also would like to

discuss in the reading group.

The Orce Man Discovery : From “A scientific revolution” to the “ Orce

Donkey ”

In the summer of 1982, Josep Gibert, Salvador Moyà-Solà and Jordi

Agustí, three palaeontologists from the Institut de Paleontologia de Sabadell,

near Barcelona, northern Spain, none of them expert in palaeoanthropology,

discovered a little cranial fragment, that they named VM-0, in the Venta

Micena site in the town of Orce, near Granada, Andalusia, in southern Spain.

At that moment, Gibert was 41 years old, was a part-time scientist while

working in a high school and was expert in fossil insectivores, that was his

PhD topic some years before. Agustí was 28 and was expert in fossil rodents

and had a little fellowship after finishing his PhD. Moyà-Solà, 27, had just

read his Ph.D. on fossil bovids.

The bone was then took to Sabadell where it was prepared and cleaned by

Moyà-Solà. After this first cleaning process, the internal part of the specimen

was still not visible, because it was still adhered to a calcareous rock.

Although Gibert, Moyà-Solà and Agustí had many doubts about the actual

nature of the bone, that was a 10 cm cranial fragment with parts of the parietal

and occipital bones, it had some characteristics, mainly a wide cranial

curvature and thinness, that allowed the discoverers to attribute it to a

hominid.1

The Orce Man, exterior (left) and interior with the rock still there (right).

But before any publication, scientists went to see Antoni Dalmau, head of

the Diputació de Barcelona, the political institution to which the Institut de

Paleontologia depended, with the bone in a box.2 This “Look what we have

found” strategy clearly shows how scientists were seeking better funding

conditions in the Institut de Paleontologia, then directed and dominated by

Miquel Crusafont, 72 at that time, mentor of the three discoverers and a

leading figure in Spanish Palaeontology and Science during the just ended

Franco's dictatorship. Perhaps due to the discoverers' doubts, Dalmau needed a

second opinion and recommended to show the fragment to Doménec

Campillo, a prestigious neurosurgeon and paleopathologist that also

confirmed that the bone belonged to a hominid.3

Pierre Mein, a French paleontologist, and Peter Andrews, an English

paleontologist from the Natural History Museum also saw VM-0 and both

confirmed that was human and recommended an international publication.4

But scientists didn't have time for this kind of publication and with the

“experts” confirmation that the bone was a hominid, they published it as

Homo sp. in Paleontologia i Evolució, the Institut de Paleontologia de

Sabadell journal.5

After this publication, in July 1983 the Diputació de Barcelona politicians

organized a joint press conference with the Junta de Andalucia politicians and

the three scientists to present the Orce bone in Granada.6 During this press

conference, politicians of both institutions also signed an institutional

scientific collaboration that included new funding for the discoverers and

excavation permit for next years.

A better understanding of the political situation of that moment is here

crucial. In October 1982, while the bone was being cleaned in Sabadell,

socialist Felipe González won the general elections, said to be the first “real”

democratic elections in Spain after a forty years dictatorship. The transition to

democracy allowed also that the different parts that conform Spain, the so-

called “Autonomias”, gain some political independence, that didn't had in the

dictatorship's central authoritarian government. The “Spain of the

Autonomias” was being shaped at precisely that moment. So, both, Catalunya

and Andalucía were in a moment of great euphoria regarding their own

political control and a public successful scientific collaboration between them

could strengthen ties, reinforce its scientific policy and legitimate their

position as independent political organisms.

Consequently, “The Orce Man", as headlines called it, had a great impact

in Spanish media, where it was described as “a scientific revolution” and as

the “discovery of the century”.7 And it seemed really a revolution. Gibert,

Agustí and Moyà-Solà claimed that VM-0 was between 0.9 and 1.6 million

years old. At that moment, and although several researches claimed an earlier

arrival of hominids to Europe, the oldest acknowledged European remains

were the “Tautavel Man” and the “Mauer” mandible, no more than 0.5 million

years old.8 For these researchers, the Orce Man antedated the “oldest

European” by nearly one million years. In the Spanish press, the Orce remain

became the “First European”.9 It has to be mentioned that at that time, Spain

was not in the European Union yet, and maybe this claim could also be part of

a much bigger effort to try to include Spain in the European Union, which

happened three years later, in 1986.

During the first year after this publication, the three discoverers used

different media in their legitimizing discourse around the Orce Man: they

gave lectures, appeared in radio and television, wrote their own newspaper

and magazine articles and were even preparing a popular science book on the

finding.10

For instance, Gibert, Agustí and Moyà-Solà published a series of full-

colour articles that described the characteristics of the bone and the site, the

scientific conditions in which it was found (not very good because of a lack of

money), and the Orce Man's prominent position in the “humanization

process”.11 In one of the series of articles with the subheading “Lack of

Funding”, when talking about Spanish palaeontology the discoverers were

quite explicit in their quest for support: “Institutions should provide a

minimum of resources [to researchers]”. On their commitment as the Orce

Man discoverers, they added: “with the necessary institutional support [...] we

hope to fulfil our responsibility”.12 Researchers presented their work in the

press in order to attract politicians’ attention in a bid to secure funding for

future research.

In June 1983, Jaume Truyols, Spanish Paleontologist, send a letter to

Crusafont, who was also his mentor, congratulating Gibert and his team for

the discovery, stating that he has read about it in newspapers and finally,

adding that this “amazing” finding will from now on appear in all the

“Anthropology” and “Human Paleontology” texts.13

It is worth noting that at that point the early scientists doubts on the nature

of the bone have completely vanished after experts statements in both the

public sphere and in the scientific sphere. In a more private, and also expert,

sphere, the doubts were too gone, as Truyols' letter shows.

Jaume Truyols to Miquel Crusafont, 23 June 1983, Crusafont archive.

During 1983 summer, the discoverers went again to Orce to excavate in

the Venta Micena site. A little exhibition with the cranial fragment was also

held in the town, where the bone was presented to residents and visitors as the

oldest European. In middle August 1983, Marie Antoinette and Henry De

Lumley, two French prestigious scientists went to the little town of Orce, were

they saw the site and the bone confirming that it was human and encouraged

the discoverers to publish it with them. 14

That same summer, Miquel Crusafont, director of the Institut de

Paleontologia, died. At that moment, the Diputació de Barcelona politicians

appointed Gibert as the new director of the Institut, and Agustí and Moyà-Solà

also obtained permanent positions there.15

In less than a year, Gibert has turned himself from a high school teacher

with a part-time interest in Palaeontology in the new head of the Institut de

Paleontologia de Sabadell, the main palaeontological institution in Catalonia

and one of the leading institutions in Spain.

After this summer campaign, the bone was send to the Museu

d'Arqueologia de Catalunya were a team under Doménec Campillo's

supervision begin to clean the internal part.16

In another newspaper article some time later, in March 1984, Agustí and

Gibert made some claims that they had not done in their first academic article.

Their new claims were that Venta Micena site was, contrary to what they had

previously claimed, a long-stay human site. Animals bones found there had a

distribution pattern that, according to the researchers, indicated human

agency. With this claim, a 10 cm cranial bone was converted into a more than

1 million years old human settlement in Europe. And as sociologist

Massimiliano Bucchi has pointed out, this shows how researchers typically

use general media to strengthen a claim that could be controversial in the

scientific media.17 Popularization is a test field, a place for speculation, a

place to release “difficult to prove” scientific hypotheses before releasing

them in the scientific media.18

As said, from October 1983 to April 1984, the internal part of the bone

was cleaned. During this cleaning process an unusual crest appeared. This

crest seemed to steer the evidence away from hominids and bring it close to

Equus, the horse and donkey family genus.19 For Campillo this crest was not

unusual in humans and was even normal in young children, that was what the

Orce bone was supposed to be.

Although Campillo's statement, the doubts raised again amongst Gibert,

Agustí and Moyà-Solà that decided to brought the fragment to Paris where,

Marie Antoinette and Henry de Lumley examined it. The de Lumleys were

famous for overseeing several excavation sites in France and abroad. They

were also the discoverers of the “Tautavel Man” and, at that moment, Henry

was director of the Prehistory Laboratory in the Musée de l’Homme and

director of the Institut de Paleontologie Humaine, both in Paris. Surrounded

by thousands of XVIIth and XIXth century animal bones from the Paris

collections, Marie Antoinette de Lumley, expert in anatomy, compared the

bone with different animal skulls and concluded that it was not a hominid

bone but rather that of a young donkey.20 The De Lumley encouraged the

discoverers to give a press conference admitting their error.21

Agustí and Moyà-Solà accepted the de Lumley's verdict but Gibert held

that a more detailed study on the bone was necessary. He believed in the

possibility that the fragment belonged to the genus Homo. Gibert left the

laboratory in complete disagreement with the de Lumleys.22

The next morning, on 12th May 1984, when the researchers arrived to the

“Estación de Francia” train station in Barcelona, found that the front cover of

the Spanish newspaper El País announced “serious evidence” that the famous

Orce Man might, in fact, be a young donkey.23 The journalist’s source was

clear: “Marie-Antoinette de Lumley last night in a phone conversation with

this newspaper...”.24

The El País front cover touched off an acrimonious and lasting

controversy. In the next four days, El País published more than 10 articles on

the Orce Man. At that point, everybody weighed in the controversy:

journalists, scientists, politicians…25

El País announced “Serious suspicions that the Orce Man is not a man but it might be a donkey

between two and four months old.” In the picture we can see Gibert (left), Agustí (center) and

Moyà-Solà (right).

In June, the satirical magazine “El Papus” published in the front cover, a

cartoon of a prehistoric man with a donkey head. In October 1984, the

Galician punk band, Siniestro Total, published a song called “Who are we?

Where do we go? From where do we come from?”, in which, among other

philosophical and metaphysical questions, the songwriter wondered “Is the

Orce Man our ancestor?”. These examples show the degree to which the

controversy had penetrated in Spanish public sphere and popular imaginary.

Next year, in May 1985, Jaume Truyols, with two other palaeontology

professors, that didn't have seen the bone, submitted an open letter to the main

Spanish newspapers saying that the bone was very uncertain, criticizing the

early popularization of the finding and hinting that Gibert was not a serious

scientist.26 According to Gibert, the palaeontology professors’ statements

harmed his scientific prestige as well as the credibility of “his” Orce scientific

project.27 This also show how important are the experts statements in this kind

of controversies. Truyols first congratulates the researchers for its “crucial”

finding but with de Lumley change of view and without Crusafont as a main

character in the Institut, changes totally his opinions.

In October 1985, and with all the controversy in the media, Josep Gibert

was fired as the director of the Institut de Paleontologia and Jordi Agustí was

appointed in his place. Gibert remained as a research fellow in the Institut.

Next year, in May 1986, the Spanish popular science magazine Muy

Interesante, published an interview with the scientist Maria Teresa Alberdi

regarding her palaeontology work. Alberdi was a palaeontologist from Madrid

who at that time was working on the geology and palaeontology of the Orce

area. The interviewer, after some general questions about palaeontology,

asked Alberdi her opinion on the Orce bone: “I haven’t seen the bone, neither

has Emiliano Aguirre, number one Spanish palaeoanthropologist […] [but]

according to what I have seen in the newspapers...”28

Scientists, even specialists on palaeoanthropology, or experts working on

palaeontology on the Orce area, did not have direct access to the bone, used

Spanish media, especially newspapers, in order to obtain information on the

Orce Man.

The summer of 1986, the Junta de Andalusia denied the excavation permit

for Venta Micena to Gibert for the first time. In the more than 20 years of

controversy, from 1986 to 2007, Gibert had excavation permit in the Venta

Micena site, where the Orce Man was found, only three times, even though he

applied for a permit every summer, and although his team excavated other

nearby sites.29

El Misterio del Hombre de Orce. El Papus. 525, June 1984.

In September 1986, Gibert attended the first World Archaeological

Congress in Southampton. His presence at this Congress was followed almost

daily in Spanish newspapers.30 Although this conference was not exclusively

palaeoanthropological, the press presented it as the place where the truth

about the Orce Man would be debated among the scientific community.31 The

day after Gibert's presentation, La Vanguardia entitled “Gibert was not

discussed in Southampton while presenting the evidence on the Orce skull”.32

The following year, 1987, Gibert received the excavation permit for Venta

Micena again.33

During this period we can see how the politicians and his policies

regarding the Orce excavation were influenced by the media presence of the

controversy. Although more research have to be made on Gibert's relation

with Junta de Andalucía politicians, we can see how, first, the de Lumley

announcement led politicians to deny the permit to Gibert. Later, Gibert's

attendance to the Southampton Conference and the presumably good

reception, allowed the permit for next summer.

In October 1987, after the excavation period, Gibert attended another

conference in Torino, Italy, which was also attended by Marie-Antoinette de

Lumley. According to Gibert, when he presented his paper on the Orce

fragment, Marie-Antoinette did not ask any questions or make any criticisms

and due to her silence nobody else did either.34

While Gibert was in Torino, Spanish newspapers announced the further

publication of the first academic paper that followed the de Lumley’s

donkey’s claim.35 The authors of this paper, published some days later in the

Spanish Journal Estudios Geológicos, were the Orce Man co-discoverers

Moyà-Solà and Agustí.36 They claimed that Gibert was using them in order to

reinforce his Orce Man claims and they wanted to clarify their own position in

the controversy. This position had to be well established in both, popular and

scientific media. In 1988, the excavation permit was denied again to Gibert.

To sum up, during a little over three years, from May 1984, when El País

published the de Lumley reclassification, to October 1987, when Moyà-Solà

and Agustí published the first scientific paper dealing with this attribution, the

supposed “scientific knowledge” that the bone VM-0 was a member of the

horse family was discussed in the press. The De Lumleys never published any

scientific article regarding the Orce fragment, so the scientific discussion did

not take place in the scientific forums such as scientific conferences, as has

already shown for the Southampton Conference and the Torino Conference, at

least according to Gibert. Thus, during these three years, the stage for the

scientific controversy was exclusively public.

1995 International Orce Human Palaeontology Conference: From “The oldest

European” to “A common and ordinary horse ”

The following years saw less media attention while Gibert and his team

continued the in-depth study on the bone fragment. During all this years,

Gibert also claimed that more than a million years ago, hominids crossed the

Gibraltar strait, a claim that wasn’t accepted in great sectors of the Spanish

scientific community.37 Some of the team members were Bienvenido

Martínez, former Gibert’s doctoral student and Orce’s animal fossils expert;

Paul Palmqvist, biologist and mathematician who had done a fractal

mathematical study to the Orce bone; and Lluís Gibert, Josep’s son and expert

in geology.38 With this team, Gibert published several papers in all kind of

scientific media. Less than 10 percent of these articles appeared in citation

index journals. The other articles were published in self-published

monographs, conference proceeding or second-line scientific journals.39

During this time, Gibert and his team also applied different studies to VM-

0 in order to get it recognized as a hominid. Some of this techniques were a

mathematical fractal analysis of the internal polemical crest and an

immunological test that looked for human albumin in the bone.40 Both tests

were positive for Gibert's interest but none of them convinced the “scientific

community”. Also both studies were very innovative regarding

paleoanthropological science. The immunological technique in

paleoanthropological remains, for instance, was applied to Orce Man for the

first time in Europe, after its development in the United States.

And the popularization effort also continued. In 1993, Gibert published an

article in La Vanguardia explaining the major achievements of his research

group, in spite of the lack of funding and excavation permits. Gibert also

established the “humankind” of the Orce bone fragment and its enormous

significance as the “first European”.41 In his article Gibert quoted several of

his scientific publications and self-published monographs, highlighting the

work capacity of his scientific team seeking to recover lost prestige in the

public forum during the years of controversy.42

This examples on popularization of the Orce Man, as the ones before the

controversy, indicate how scientists used media, in this case newspapers, in

order get public, journalistic and institutional favour.

As we can see Gibert used all kinds of media, from the press to peer-

review scientific journals, from popular science books to self-published

monographs, and even children books, to defend his controversial claims

across the wide range of publics and media.

In 1995, after more than ten years of controversy, Gibert managed to hold

an International Human Palaeontology Conference in Orce. With this

conference, media attention reappeared.43 In the opening and closing session

of the Conference, with several reporters and television cameras in the

audience, Gibert gave a talk about his “struggle against everybody” during all

this controversy years and how this Conference is the final consolidation of

his own ideas about the Orce Man, and his own “new paradigma” in Kuhnian

terms. Gibert usually used Kuhn and his paradigms in order to pictures

himself as a “not accepted revolutionary”.44 Alongside Gibert, the Orce

Mayor, a Junta de Andalucía politician and the famous paleoanthropologist

Philip Tobias, also talked about Gibert's great work in the region.

In his popular science book, Gibert explains that during the conference,

journalists attended to the sessions, asked questions to scientists and visited

palaeontological sites.45 In the Conference, Gibert and his team presented

several lines of evidences for the acceptance of the Orce Man.46

The cranial fragment and other evidence of the hominids presence in the

Orce region, as stone tools, were displayed during the Conference to both

attendant scientists and general public.

In their coverage of the Conference, newspapers included several scientists

opinions on the fragment and on the Venta Micena site and journalists also

reviewed some of the sessions. According to El País, in the opening session,

the prestigious scientists Philip V. Tobias and F. Clark Howell stated they

were “convinced that the Orce skull belongs to a hominid.”47 Also El País

highlighted Paul Sondaar's presentation in the Conference. Sondaar was a

Netherlander researcher working in Indonesia who claimed that 0'7 million

years ago, hominids crossed a 20 km sea gap to reach Flores Island.

According to the journalist, this could support Gibert's hypothesis of Gibraltar

strait Orce hominids crossing.48 Information on the Conference appeared in

the newspapers and scientists gave their opinion on the bone and on the site in

Spanish television and newspapers, which became the space where a scientific

forum was presented. Moreover, the Orce Conference organizing committee,

mainly Gibert's team, set up a big screen in Orce's main square to allow the

town's inhabitants to follow the conference's scientific debates.

Philip Tobias in front of the Orce Man bone in an interview for the Spanish Television, September

1995.

So, Gibert used the organization of the Conference as a great persuasion

tool guided to convince three different groups: the attendant scientists, the

politicians and the public opinion. Gibert used several “weapons”, like the

presence of international scientific figures, the display of the actual Orce Man

bone or his own rhetoric in order to get his research legitimated in the public

sphere and validated by the so-called scientific community.

During the Conference, La Vanguardia, another major Spanish newspaper,

published an article with the title “An international conference ensures that

the Orce Man is the oldest European”.49 In the closing session of the

Conference, Diego Valderas, Andalusian Parliament president, promised

funding and excavation permits to Gibert and finally stated that “Gibert had

won the public opinion battle”.50

But this “public victory” did not last too long. Next month, El País

published statements on the Orce bone by José María Bermúdez de Castro

and Eudald Carbonell, both directors of the well-known Spanish site

Atapuerca.51 Carbonell criticized Gibert's scientific rigour and Bermúdez de

Castro, who attended the Orce Conference, stated that “according to the

fossils, there is no Orce Man”. 52

Next summer, 1996, two of Gibert’s former collaborators, Bienvenido

Martínez and Paul Palmqvist, together with Alain Turq, a French

archaeologist who had studied stone tools from another site near Venta

Micena, announced first to the local Orce's magazine, then to the Andalusian

television and finally to the national press their split from Gibert’s team. They

argued that were tired of Gibert’s lack of funding and of his “obsession” with

the Orce fragment. Palmqvist also accused Gibert of fraud. According to

Palmqvist, Gibert gave him a simplified sketch of the bone, which altered the

results of his fractal analysis.53

After this new very local outbreak of the controversy, the Andalusia

politicians denied the excavation permit to Gibert again.54

Almost a year later, Moyà-Solà and Palmqvist published two scientific

articles regarding the Orce bone in the June 1997 issue of the international

Journal of Human Evolution. In his article, Palmqvist revised his fractal

analysis with a new Orce bone sketch: the bone was no longer human, and

was closer to the horse family. Moyà-Solà’s paper, entitled “The Orce Skull:

Anatomy of a Mistake”, addressed VM-0 anatomy and concluded that VM-0

was “just a common and ordinary horse”.55 The publication of these papers

appeared in Spanish newspapers which noted that this new “demolishing

evidences” were published in a prestigious and international journal.56 Both El

País and La Vanguardia reproduced exactly the same sentence: the Orce Man

is “a common and ordinary horse”.57

In 2007, after years of less media attention but an ongoing controversy

over the Orce bone and the Venta Micena excavation permits, Josep Gibert i

Clos died due to a fulminating cancer. His ashes were scattered in the Venta

Micena site.58 Although the Orce Man regularly appeared in Spanish

magazines and newspapers, with Gibert, the Orce Man's main defender, the

controversy itself also fade away.

Conclusion: People, places and strategies

The Orce Man is a lasting and complicated controversy. This paper only

offers an account of it that allow an accurate analysis of its participants and

scenarios. First of all, we can see how centre and periphery relations are

crucial in this controversy. French scientists acted as a dominant figure

regarding young Spanish scientists, situated in a less prominent country

regarding science and palaeonthorpology. Its important to notice how at the

beginning, when the bone was of highest importance, French scientists

travelled to Orce. But later, when problems begin, Spanish scientist were

obligated to travel to Paris to get the bone compared and finally rejected.

The early popularization effort of the discovery, that benefited both

politicians and scientists, caused that when the de Lumleys needed to stablish

their new opinion, went directly to a newspaper, a fast and easy publication,

that established this new classification for almost three years until the first

scientific publication. The option chosen by the de Lumleys also provoked

that the Spanish media became the scenario of the scientific debate. Experts

used media in order to get information on the case, and new “actors” as

politicians, journalists or the lay public also were involved in the scientific

discussion. From then on, when new scientific opinions appeared in the

scientific sphere, also had to had a public appearance in order to validate the

new claim in both spheres.

Throughout all the controversy, but specially at the early stages, the

“experts” opinion was fundamental in the way that the debate developed.

Politicians, journalists, the publics and other scientists were influenced by

these experts opinions that allowed both the validation and the rejection of the

Orce Man and crucially shaped the way the Orce Man research was done.

The way that politicians had a role in the controversy is also of the highest

importance. Beyond the influence that they received from media and experts,

politicians followed their own agenda in order to use science in their own

interests. Agenda and interests that were different for the Diputació de

Barcelona, the Junta de Andalucía and the Orce Town Hall. While the Orce

Mayor aimed that this town became a tourist destination, the higher level

politicians looked for a legitimation of their position and government

thorough a major scientific achievement.

As this last example shows, in my analysis, all this places and people

highlight the different strategies used in order to fulfil different interests. Prior

to the controversy, Gibert, Agustí and Moyà-Solà used media popularization

in order secure funding, that at the end came in the form of permanent

positions in the Institut.

During the controversy, Gibert used a “overpublication” strategy that

allowed him to disseminate his ideas and “spread his cause”. The 1995

Conference was used by Gibert and his team with the same purpose. Agustí

and Moyà-Solà used media in order to increase impact of their different

opinions on the bone.

To sum up, as we can see in several examples in this paper, experts,

politicians and media had a prominent role in the creation, legitimation,

circulation and validation of the Orce Man. This case points to that this

“actors” also have a prominent role in the way that scientific knowledge is

created, legitimated, circulated and validated in late 20th-century

paleoanthropology.

1Interview to Jordi Agustí.2 Interview to Jordi Agustí.3 Interview to Campillo.4Gibert, Josep. El Hombre de Orce, los Hominidos que llegaron del Sur. Córdoba: Almuzara, (2004).5Gibert, J.; Agustí, J.; Moya-Sola, S. "Presencia de Homo sp. en el yacimiento del Pleistoceno inferior de Venta Micena (Orce, Granada)" Paleontologia i Evolucio, (1983), 1-9.6Aguilar, José. “El hallazgo del Hombre de Orce puede suponer una revolución en estudio de la especie humana” El País June 14, 1983.7“Revolución científica” Aguilar. Díaz-Rojo has analyzed the media rhetoric used in these first news of the discovery: Díaz Rojo, José Antonio. “Retórica científica en la prensa. El hallazgo paleontológico del cráneo de Orce (1983)” in: La circulación del saber científico en los siglos XIX y XX Díaz Rojo, José Antonio (ed.), (2011), 99-128.8Gibret, El Hombre de Orce, 273-294.9For instance: De Semir, Vladimir. “Tres paleontólogos catalanes descubren el hombre más antiguo de Europa y Asia” La Vanguardia June 12, 1983, 51.10An example of a lecture in: “Día a Día” La Vanguardia, Febraury 22, 1984, 53. Articles in newspapers and popular science magazines: Agustí, Jordi; Gibert, Josep; Moyà-Solà, Salvador. “El Hombre de Orce”. Revista de Arqueologia, 1983, 29, 16-21. Agustí, Jordi; Gibert, Josep; Moyà-Solà, Salvador. “Características del Hombre de Orce” La Vanguardia. August 21, 1983. And for the popular science book: Piñol, Rosa Maria, “La nova editorial catalana Empúries publicará diveres obres de Riba” La Vanguardia March 15, 1984.11Agustí, Gibert and Moyà-Solà, “Características del Hombre de Orce.”12“Las instituciones deben dotarles con un mínimo de medios” and “con el apoyo institucional necesario […] esperamos cumplir con nuestro cometido” Agustí, Gibert and Moyà-Solà, “Características del Hombre de Orce.”13Letter from Jaume Truyols to Miquel Crusafont, 25th June 1983. Crusafont Archive.14Gibert, El Hombre de Orce,.15Gibert, El Hombre de Orce,.16 Interview to Doménec Campillo, and Gibert, El Hombre de Orce,.17Bucchi, Massimiano. “When scientists turn to the public: Alternative routes in science communication” Public Understanding of Science, (1996), 5, 375-394.18Hochadel and Gregory had show, respectively, how popular-science-books and science fiction can work in the same way: Hochadel, Oliver. “Atapuerca-the Making of a Magic Mountain. Popular Science Books and Human-Origins-Research in Contemporary Spain.” In Communicating Science in 20th Century Europe. A Survey

on Research and Comparative Perspectives, Arne Schirrmacher (ed.), 149-163, 2009. Hochadel, Oliver. “Atapuerca-the Making of a Magic Mountain. Popular Science Books and Human-Origins-Research in Contemporary Spain.” In Communicating Science in 20th Century Europe. A Survey on Research and Comparative Perspectives, Arne Schirrmacher (ed.), 149-163, 2009. Gregory, Jane. “The Popularization and excommunication of Fred Hoyle’s 'life-from-space' theory” Public Understanding of Science, 2003, 12, 25-46.19 Campillo, Domènec. El Cráneo infantil de Orce: el homínido más antiguo de Eurasia. Bellaterra: Edicions Bellaterra (2002).20Interview to Jordi Agustí. 21 Gibert, El Hombre de Orce, 48.22 Ibid, 48.23 Relaño, Alfredo. “Serios indicios de que el cráneo del 'hombre de Orce' pertenece a un asno”. El País May 12, 1984, 1.24“ Marie-Antoinette de Lumley en conversación telefónica con este periódico...” Relaño, Alfredo. “Serias sospechas de que el 'hombre de Orce' no es un hombre, sino que podría ser un asno de dos a cuatro meses de edad”. El País May 12, 1984, 22.25For example: Editorial, “Hombre o borrico” El País. May. 15, 1984. or Relaño, Alfredo. “La Junta de Andalucía valora con cautela las dudas sobre el origen del 'hombre de Orce'” El País May, 13, 1984.26De Renzi, Miquel; Porta, Jaume; Truyols, Jaume, “Nota sobre paleontologia.” Avui. March 6, 1985, 10.27Gibert, El Hombre de Orce, 56-57.28“Yo no lo he visto, y tampoco Emiliano Aguirre, número uno español en paleontología humana […] [pero] a juzgar por lo que ha salido en la prensa...” Torreiglesias, Manuel. “Los Fósiles son patrimonio de la humanidad” Muy Interesante. May. 1986, 60, 129-131, 130.29Gibert, El Hombre de Orce, 105. 30For instance: Moreno, Manuel. “El cráneo de Orce es humano, según confirma el Congreso Arqueológico Mundial” El País September 9, 1986. 31 Paredes, José Antonio. “Gibert: las dudas sobre el 'hombre de Orce' acabarán en

Southampton” La Vanguardia August 23, 1986.32 Piñol, Rosa Maria, “Gibert no fue discutido al presentar las pruebas sobre el cráneo de Orce”, 28.33Gibert, El Hombre de Orce.34Gibert, El Hombre de Orce, 78.35 Mercadé, Josep. “Los colaboradores de Gibert dicen que el cráneo de Orce pertenece a un equino”. La Vanguardia. October 2, 1987, 40.

36 Agustí, Jordi; Moyà-Solà, Salvador. “Sobre la identidad del fragmento craneal atribuido a Homo sp. de Venta Micena (Orce Granada)” Estudios Geológicos 1987. 42: 538–443.37 For instance, Iglesias, Alfredo, Gibert, Josep and Gibert, Lluís. “La penetración de los homínidos por el Estrecho de Gibraltar en el contexto general de su dispersión”. Gallaecia. 1998, 17. 29-48.38The "fractal dimensions", elucidated through complicated mathematical formulas, were used in this case to establish the complexity of the sutures. The simpler is the suture, more likely to place the fragment within the genus Homo. Gibert, Josep ; Palmqvist, Paul. “Fractal analysis of the Orce skull sutures”. Journal of Human Evolution. 1995. 28: 561–575.39According to himself, by year 2000, Gibert had published more than 130 articles, 16 in Citation Index Journals and 11 of the latter in international journals. Gibert, Josep; Gibert, Lluís. “Las investigaciones de Orce y los medios de Comunicación”. II Simposio Latino sobre Geología, Medio ambiente y Sociedad, 2000, 227-232.40 Borja,Concepción; García-Pacheco, Marcos; García-Olivares, Enrique; Scheuenstuhl, G.; Lowenstein,J. Immunospecificity of albumin detected in 1.6 million-year-old fossils from Venta Micena in Orce, Granada, Spain. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1997; 103: 433-441.41Gibert, Josep. “El primer ser humano de Europa” La Vanguardia. May 1, 1993, 10-11.42Gibert, “El primer ser humano de Europa,” 10.43In the days before, during and after the conference, La Vanguardia published four articles on the conference, El País, five and ABC also five. The conference had even some abroad attention: Denison, Simon “1.8 million-year-old human presence claimed in Spain”. British Archaeology. 1995, 7.. Weimer, Wolfram. “Wo lebte der erste Europäer?” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September. 7, 1995, 12.44Gibert, El Hombre de Orce,45Gibert, El Hombre de Orce, 91.46 Gibert, Josep. “Human remains in Orce and Cueva Victoria” International

Conference on Human Paleontology, (Orce, Spain), 17-18, Granada, 1995.47Tobias was, for example, one of the describers of Homo habilis with Louis Leakey. Howell is also a major palaeoanthropologist from the University of California. "Convencidos de que el cráneo de Orce pertenece a un homínido", Arias, Jesús. “Expertos creen que los fósiles de Orce son anteriores a los de Atapuerca” El País 5 September 1995. 48Cervera, José. “La difícil ruta desde África” El País September 1995.49Efe, “Un congreso internacional asegura que el Hombre de Orce es el europeo más antiguo”.

50F.R.A. “La Consejería promete apoyo económico para el yacimiento de Orce” ABC September 9 1995, 39.51For an exhaustive account of Atapuerca and its relation to the media see Hochadel, El mito de Atapuerca. 52“A partir de los fósiles presentados, el hombre de Orce no existe”. Rivera, Alícia. “Paleontólogos y geólogos cuestionan la existencia del 'hombre de Orce'” El País. October 6 1995.53 De León-Sotelo, Trinidad, “Orce, una polémica que no fosiliza” ABC August 8, 1996, 47. 47. Editorial, “Polémica en Orce” ABC August 11, 1996, 49.54 Gibert, El Hombre de Orce,55 Moyà-Solà, Salvador and Köhler, Meike. “The Orce skull: anatomy of a mistake” Journal of Human Evolution 33, 91–97(1997).56“pruebas demoledoras”. Editorial, “Los científicos hallan pruebas demoledoras contra la autenticidad del hombre de Orce” La Vanguardia, August 18, 1997, 57“Un caballo común y ordinario.” Ruiz de Elvira, Malen. “El fósil del 'hombre de Orce' pertenece en realidad a un caballo, según los científicos” El País, August 17, 1997.58Planas, Mónica, “Un hombre marcado por un fósil” La Vanguardia. October 9, 2007, 37